Abstract

Sporotrichosis is an endemic mycosis caused by the species of the Sporothrix genus, and it is considered one of the most frequent subcutaneous mycoses in Mexico. This mycosis has become a relevant fungal infection in the last two decades. Today, much is known of its epidemiology and distribution, and its taxonomy has undergone revisions. New clinical species have been identified and classified through molecular tools, and they now include Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto, Sporothrix brasiliensis, Sporothrix globosa, and Sporothrix luriei. In this article, we present a systematic review of sporotrichosis in Mexico that analyzes its epidemiology, geographic distribution, and diagnosis. The results show that the most common clinical presentation of sporotrichosis in Mexico is the lymphocutaneous form, with a higher incidence in the 0–15 age range, mainly in males, and for which trauma with plants is the most frequent source of infection. In Mexico, the laboratory diagnosis of sporotrichosis is mainly carried out using conventional methods, but in recent years, several researchers have used molecular methods to identify the Sporothrix species. The treatment of choice depends mainly on the clinical form of the disease, the host’s immunological status, and the species of Sporothrix involved. Despite the significance of this mycosis in Mexico, public information about sporotrichosis is scarce, and it is not considered reportable according to Mexico’s epidemiological national system, the “Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica.” Due to the lack of data in Mexico regarding the epidemiology of this disease, we present a systematic review of sporotrichosis in Mexico, between 1914 and 2019, that analyzes its epidemiology, geographic distribution, and diagnosis.

Keywords: Sporothrix spp., Mexico, Epidemiology, Diagnosis

Introduction

Sporotrichosis is an infection caused by the thermodimorphic fungi of the genus Sporothrix. The disease is characterized by nodular lesions in the skin and in the subcutaneous tissue, that subsequently ulcerate, mainly affecting the lymphocutaneous system, but rarely other organs. The transmission pathways are associated with organic matter, animal excreta, or also zoonosis [1–3]. Sporotrichosis is usually acquired through traumatic inoculation with fomites (spines, debris), contaminated soil, and animal scratches [1, 4–6]. Because plant thorns or bushes are often the source of the infection, the disease is commonly known as the “rosebush mycosis” or the “gardener’s mycosis” [6]. Rarely can it be acquired by inhalation of spores and produce a primary lung infection [1, 7]. This mycosis is also widely prevalent in endothermic animals, such as cats, occasionally dogs, armadillos, rats, birds, and parrots, which are a source of zoonotic transmission [5]. Years ago, it has been shown that sporotrichosis can evolve as a severe disseminated disease with visceral and osteoarticular involvement, particularly in individuals with AIDS, individuals receiving immunosuppressive treatments, and other causes of immunodeficiencies, such as diabetes and chronic alcoholism [1, 8].

Sporotrichosis can be classified as cutaneous (which is the most common form) or extracutaneous [1, 6]. However, there are other classification approaches based on the clinical characteristics of the infection, and they are divided as follows: skin (lymphocutaneous, fixed cutaneous, and multiple inoculations), mucous membrane (ocular, nasal, and others), systemic (osteoarticular, disseminated cutaneous, pulmonary, neurological, and other locations/sepsis), and immunoreactive (erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, and reactive arthritis) [6]. Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is the most common form, which predominantly affects the upper extremities (forearm and hands) and the facial region. When there is no dissemination, the form is known as fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis. Ocular sporotrichosis is the most common form among the mucous membrane infections, causing conjunctivitis, episcleritis, uveitis, choroiditis, and retrobulbar lesions. Systemic sporotrichosis is the least frequent of all, and it is mainly associated with individuals with immunosuppression factors such as AIDS, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and lymphoma, or individuals under immunosuppressive treatment [1, 6, 8]. Some patients may present a spontaneous resolution of the infection, and there is also an immunoreactive form, in which an exacerbated immune response against the fungus may occur [6].

Although the mycosis is distributed worldwide, most of the cases come from tropical and subtropical areas in Latin America, Africa, and Asia [5]. In Europe, the cases have been recorded intermittently in countries like Italy, Spain, Portugal, the UK, and Turkey [9]. In Latin America, the estimated prevalence rate of sporotrichosis is 0.1 to 0.5%, particularly in Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Mexico, Uruguay, and Venezuela, while in Argentina, Ecuador, and Panama, it ranges from 0.01 to 0.02%. In some regions of South America, the disease occurs most frequently during the wet seasons of summer and autumn. In Mexico, the incidence rate increases during the cold and dry seasons, mainly in regions with a temperate and humid climate [5, 10]. There is no substantial evidence about the prevalence of the disease by age or sex, and it is often associated with agriculture, gardening, mining, or other outdoor activities [11].

Sporotrichosis can be diagnosed by a combination of clinical and epidemiological data, and laboratory tests. The transmission of sporotrichosis occurs in open spaces; therefore, other diseases such as cutaneous leishmaniasis, tuberculosis, tularemia, leprosy, and some neoplastic and bacterial lesions should be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially if there are no tools or infrastructure for mycological tests [12, 13].

Traditionally, sporotrichosis is diagnosed considering the results from clinical and laboratory studies. Clinical studies usually provide a presumptive diagnosis, while laboratory procedures are necessary to establish the etiology of the disease [14]. The gold standard diagnosis for sporotrichosis is the culture of clinical samples—in Sabouraud dextrose medium agar (SDA) at 25 to 28 °C—that are obtained from active lesions, pus, secretions, or biopsy. In this medium, the fungus forms filamentous colonies. The typical colony morphology in SDA is a thin mycelium with sessile and sympodial microconidia, while in rich media such as blood and chocolate agar at 37 °C, the fungus forms yeast colonies of elongated blastoconidia [6]. The direct examination of biological samples with 10% potassium hydroxide is useless for the diagnosis of human sporotrichosis, due to the scarcity of fungal elements in the lesions, particularly in the lymphocutaneous and fixed cutaneous forms. However, it is convenient to discard other sporotrichoid skin infections [15]. The histopathological analysis is another alternative method, mainly for disseminated forms [16].

In this article, we present a review of sporotrichosis in Mexico through a systematic revision of articles including the following criteria: the epidemiological data of the patients, such as age, gender, geographic origin, diagnosis, and treatment, published from 1914 to 2019.

Methods

The databases used in the search were Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, MEDLINE, and SciELO, as well as the archives from the Faculty of Medicine Library, UNAM. The search was performed using the words Sporothrix, Sporothrix schenckii, and sporotrichosis.

Results

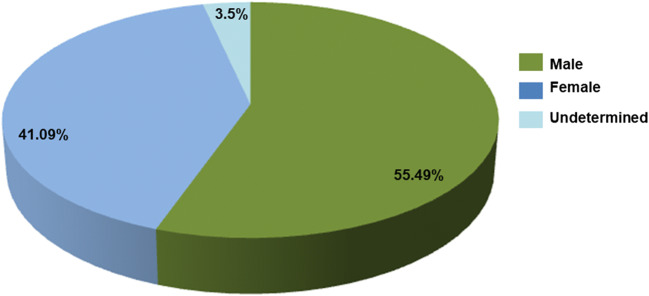

A total of 40 articles were selected considering the patients’ epidemiological data, such as age, gender, geographic origin, diagnosis, and treatment (Table 1). From these data, 2762 cases with different clinical presentations, such as lymphocutaneous, fixed, disseminated, and atypical sporotrichosis, were found. The most frequent presentation was lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis (67.29%), followed by the fixed (26.23%), the disseminated (3.43%), and the atypical (0.39%) presentations (Fig. 1). Furthermore, according to this revision, there is a higher incidence in males (55.49%), while female individuals showed a lower incidence (41.09%). Regarding age, this review found patients with sporotrichosis in the 0 to > 61 age range, including the most affected group aged 0–15 years (34.15%), followed by other groups aged 16–30 years (16.89%), 31–45 years (12.91%), 46–60 years (14.5%), and, finally, > 61 years (12.69%) (Fig. 2). Moreover, the data obtained from this review showed that the highest number of sporotrichosis cases in Mexico are located, in descending precedence, in Jalisco (n = 1698), Mexico City (n = 162), Puebla (n = 123), Guerrero (n = 84), and Guanajuato (n = 66). In contrast, in the states of Sonora, Coahuila, Campeche, Baja California Sur, Tabasco, Tlaxcala, Quintana Roo, and Yucatán, there are no sporotrichosis cases recorded until now (Fig. 3). The cases with the highest frequency, found in this study, included students (24.67%), peasants (23.01%), and housewives (19.89%) (Table 2). The laboratory diagnosis of sporotrichosis is mainly carried out using conventional methods (sample culture, isolation of the etiologic agent, macro- and micromorphology, histopathology, and sporotrichin skin test (ST)). Thirty-seven of the articles reviewed included at least one of the aforementioned diagnostic tests, and in 75% of them, immunodiagnostic methods were present; 14 papers reported the use of ST, three used the indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), one used the immunodiffusion method, and another one used the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) method (Table 1).

Table 1.

Epidemiological data on sporotrichosis in Mexico

| Reference | Cases (n) | Age (n) | Gender | Geographical origin | Clinical presentation | Source of infection | Culture | Laboratory diagnosis tests | Treatment | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gayón [17] | 1 | 40 | F | Ver | L | UD | Positive | Macro- and micromorphology | Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Latapi [18] | 1 | 3 | M | Mich | L | UD | Positive |

Macro- and micromorphology ST |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Lavalle [19] | 220 |

0–15 (60) 16–30 (73) 31–45 (31) 46–60 (28) 61 > (25) UD (3) |

M (116) F (104) |

CDMX (89) Gto(27) Pue (16) Jal (13) Hgo (12) Ver (11) Mex (10) Mich (8) Oaxaca (8) SLP (6) Zac (4) Qro (4) Gro (4) Mor (3) Ags (1) Col (1) Dgo (1) Chis (1) Tamps (1) |

L (129) F (62) D (11) A (6) UD (12) |

UD | Positive (135) |

Macro- and micromorphology ST Biopsy |

Amphotericin B Potassium iodide |

S. schenckii |

| Mayorga et al. [20] | 822 |

< 1–15 (239) 16–30 (154) 31–45 (114) 46–60 (132) > 61 (102) UD (81) |

M (478) F (344) |

Jal (539) Nay (10) Zac (9) Mich (4) Gto (1) UD (259) |

L (567) F (184) D (10) UD (61) |

UD | UD | UD | UD | UD |

| Espinosa-Texis et al. [21] | 50 |

< 1–15 (239) 16–30 (154) 31–45 (114) 46–60 (132) > 61 (102) UD (81) |

M (31) F (19) |

Pue (16) CDMX (14) Jal (8) Oaxaca (4) Gro (3) Hgo (2) Gto (1) Ags (1) Zac (1) |

L (41) F (8) D (1) |

UD | Positive (47/50) |

ST Histopathology IFA |

UD | S. schenckii (94%) |

| Padilla et al. [22] | 1 | 63 | M | CDMX | L | UD | Positive |

Direct exam (+) X-ray |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Padilla and Saucedo [23] | 1 | 22 | M | Pue | D | UD | Positive |

ST X-ray Histopathology |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Padilla et al. [24] | 1 | 18 | M | Hgo | F | UD | Positive |

Direct exam (+) Histopathology ST X-ray |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Padilla et al. [25] | 1 | 62 | F | Pue | L | UD | Positive | Histopathology | Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Vega-Morquecho et al. [26] | 1 | 58 | F | Gto | D | UD | Positive |

Direct exam (+) ST Histopathology X-ray |

Potassium iodide Itraconazole | S. schenckii |

| Padilla et al. [27] | 120 (retrospective study 1956–2003) |

Infants (6) Preschoolers (20) Schoolers (39) Adolescents (55) |

M (61) F (59) |

CDMX (38) Mex (15) Pue (14) Ver (14) Gto (11) Oaxaca (6) Hgo (4) Chis (3) Mich (3) Mor (3) Qro (3) Gro (2) SLP(2) Jal (1) Zac (1) |

L (98) F (22) |

UD | Positive (120) | UD | UD | UD |

| Méndez-Tovar et al. [28] | 1 | 68 | M | Mich | F | UD | Positive |

Direct exam. (+) Histopathology |

Itraconazole | S. schenckii |

| Poletti et al. [29] | 4 | 7 | M | Jal | F | Cat scratch | Positive | Direct exam. (+) | Potassium iodide Itraconazole | S. schenckii |

| 9 | M | Jal | F | UD | Positive | Histopathology | Itraconazole | S. schenckii | ||

| 9 | M | Oaxaca | F | UD | Positive |

Direct exam (+) ST |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 11 | M | Ags | F | Squirrel bite | Positive | Histopathology | Itraconazole | S. schenckii | ||

| Carrada-Bravo [30] | 5 | 1. 9 | F | Gto | L | UD | Positive | Histopathology | Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| 2.9 | F | Gto | L | UD | Positive |

ID IFA |

Itraconazole | S. schenckii | ||

| 5 | F | Gto | L | UD | Positive |

ID IFA |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii | ||

| 9 | M | Gto | F | UD | Positive | UD | Potassium iodide | S. schenckii | ||

| 13 | F | Gto | F | UD | Positive | UD | Potassium iodide | S. schenckii | ||

| Macotela-Ruiz and Nochebuena-Ramos [31] | 55 |

0–15 (17) 16–30 (13) 31–45 (3) 46–60 (12) > 61 (10) |

M (33) F (22) |

Pue |

L (31) F (17) D (4) A (3) |

UD | Positive (55) |

Macro- and micromorphology ST |

Potassium iodide Itraconazole Ketoconazole |

S. schenckii |

| Muñoz-Estrada et al. [32] | 1 | 12 | M | Sin | L | UD | Positive | Macro- and micromorphology | Itraconazole | S. schenckii |

| Carrada-Bravo [33] | 1 | 42 | M | UD | A | UD | Positive |

ST ELISA IFA |

Itraconazole | S. schenckii |

| Padilla et al. [34] | 1 | 13 | M | Oaxaca | L | Trauma with plants | Positive |

Macro- and micromorphology ST Histopathology |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Padilla et al. [35] | 1 | 54 | F | Oaxaca | L | UD | Positive |

Macro- and micromorphology Direct exam (+) ST |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Arenas et al. [36] | 13 | 72 | M | Mich | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | UD |

| 72 | F | Pue | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 60 | F | SLP | F | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 63 | F | CDMX | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 60 | F | Gto | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 55 | M | Gto | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 76 | M | Gto | D | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 75 | F | Gro | D | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 64 | M | Gto | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 24 | M | Pue | D | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 9 | M | Oaxaca | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 35 | M | Gto | D | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 12 | M | Dgo | L | UD | Positive | UD | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| Bada del Moral et al. [37] | 5 | 58 | F | Ver | L | UD | Positive |

Biopsy H-E |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| 32 | M | Ver | F | Ant bite | Positive |

Histopathology H-E |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii | ||

| 25 | M | Ver | L | UD | Positive |

Histopathology H-E |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii | ||

| 26 | M | Ver | F | Motorcycle accident | Positive | Histopathology | Potassium iodide | UD | ||

| 75 | F | Ver | L | UD | Positive |

Histopathology PAS |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| Bonifaz et al. [38] | 25 | 0.8–17.5 | UD | UD |

L (16) F (8) D (1) |

Trauma with plants (17) Squirrel scratch (2) Squirrel bite (1) Cat scratch (1) Rat bite (1) |

Positive (24/25) |

Macro- and micromorphology Dimorphism ST Biopsy H-E and PAS |

Potassium iodide Itraconazole | S. schenckii |

| Chávez et al. [39] | 1 | 78 | F | UD | D | Excoriation on lip from fall | Positive |

Histopathology PAS |

Amphotericin B | S. schenckii |

| Fonseca-Reyes et al. [40] | 1 | 40 | M | UD | D | UD | Positive |

Histopathology PAS |

Amphotericin B | S. schenckii |

| Munguía et al. [41] | 10 | 62 | F | Pue | L | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii |

| 44 | F | Pue | L | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 49 | M | Pue | F | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 39 | M | Pue | L | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 27 | F | Pue | L | Trauma with plants | Positive | ST | UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 34 | F | Pue | L | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 19 | F | Pue | L | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 78 | F | Pue | F | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 19 | F | Pue | F | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| 29 | M | Pue | F | Trauma with plants | Positive |

ST Reproduction of sporotrichosis in mice |

UD | S. schenckii | ||

| García-Vargas et al. [42] | 133 | < 15 |

M (76) F (57) |

Nay (4) Jal (75) UD (54) |

L (72/133) F (58/133) D (3/133) |

UD | Positive (133) | Macro- and micromorphology | UD | S. schenckii |

| Barba-Borrego et al. [43] | 1 | 12 | M | UD | L | UD | Positive | Macro- and micromorphology | Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Roldán-Marín et al. [44] | 1 | 53 | F | UD | F | UD | Negative |

Histopathology ST |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Gutierrez-Morales et al. [45] | 1 | 39 | M | Ver | A | UD | Positive | Histopathology | Potassium iodide antifungal UD | S. schenckii |

| Romero-Cabello et al. [46] | 1 | 36 | M | Pue | D | UD | Positive |

Histopathology Wright and Giemsa ST |

Itraconazole Potassium iodide Amphotericin B |

S. schenckii (sensu stricto) |

| Rojas-Padilla et al. [47] | 1 | 13 | M | Oaxaca | L | Spider bite | Positive |

Macro- and micromorphology ST |

Potassium iodide | S. schenckii |

| Chávez López et al. [48] | 1 | 36 | F | Gro | D | UD | Positive |

macro and micromorphology Biopsy |

Potassium iodide | Sporothrix spp. |

| Palma-Ramos et al. [49] | 11 | UD | UD | UD | F | UD | UD | Biopsy | UD | Sporothrix spp. |

| Cotino Sánchez et al. [50] | 1 | 68 | M | Dgo | D | UD | Positive | Biopsy | Itraconazole | Sporothrix spp. |

| Estrada-Castañón et al. [51] | 73 |

Children (37) Adults (36) |

M (33) (45.2%) F (40) (54.8%) |

Gro |

L (41) F (24) D (8) |

UD | Positive |

Macro- and micromorphology (73) ST (44) Biopsy (29) |

Potassium iodide |

Sporothrix spp. S. schenckii |

| Rojas et al. [52] | 39 | UD | UD |

CDMX (17) SLP (3) Col (2) NL (3) Pue (4) Oaxaca (6) Jal (2) Ver (2) |

L (36) F (2) D (1) |

UD | Positive |

Macro- and micromorphology Analysis of the partial sequence of the calmodulin gene |

UD |

S. schenckii (38) S. globose (1) |

| Rangel-Gamboa et al. [53] | 22 | UD |

SLP (8) Jal (1) Zac (1) Pue (3) Mich (1) CDMX (2) Qro (2) Gto (2) Mor (1) Mex (1) |

L (17) F (4) D (1) |

Trauma with plant (Crataegus pubescens) (1) Rodent bite (1) UD (20) |

Positive | Analysis of the partial sequences of the calmodulin and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase genes | UD |

S. schenckii (19) S. globosa (4) |

|

| Ochoa-Reyes et al. [54] | 1 | 84 | F | Chih | F | UD | Positive |

Macro- and micromorphology Analysis of the partial sequence of the calmodulin gene |

Itraconazole | S. schenckii (sensu lato) |

| Puebla-Miranda et al. [55] | 1 | 23 | M | BC | L | Trauma with rock | Positive | Macro- and micromorphology | Potassium iodide | S. schenckii (sensu stricto) |

| Mayorga-Rodriguez et al. [10] | 1134 |

< 1–15 (292) 16–30 (199) 31–45 (156) 46–60 (200) ≥ 61 (199) UD (88) |

M (669) F (465) |

Jal (1057) Nay (23) Zac (20) Mich (19) Gto (13) Ver (1) Chih (1) |

L (782) F (308) D 44 |

UD | UD | UD | UD | Sporothrix complex |

IFA, indirect immunofluorescence assay; UD, undetermined; ST, skin test; ID, immunodiffusion; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff stain; H-E, hematoxylin-eosin stain; M, male; F, female; L, lymphocutaneous; F, fixed; D, disseminated; A, atypical; Ags, Aguascalientes; BC, Baja California; Col, Colima; Chis, Chiapas; Chih, Chihuahua; CDMX, Ciudad de México; Dgo, Durango; Gto, Guanajuato; Gro, Guerrero; Hgo, Hidalgo; Jal, Jalisco; Mex, Estado de México; Mich, Michoacán; Mor, Morelos; Nay, Nayarit; NL, Nuevo León; Oaxaca, Oaxaca; Pue, Puebla; Qro, Querétaro; SLP, San Luis Potosí; Sin, Sinaloa; Tamps, Tamaulipas; Ver, Veracruz; Zac, Zacatecas

Fig. 1.

Frequency of clinical presentations of sporotrichosis in Mexico from 1914 to 2019

Fig. 2.

Frequency of sporotrichosis by age groups in Mexico from 1914 to 2019

Fig. 3.

Geographic distribution of sporotrichosis cases in Mexico from 1914 to 2019. Ags, Aguascalientes; BC, Baja California; BCS, Baja California Sur; Camp, Campeche; Coah, Coahuila; Col, Colima; Chis, Chiapas; Chih, Chihuahua; CDMX, Ciudad de México; Dgo, Durango; Gto, Guanajuato; Gro, Guerrero; Hgo, Hidalgo; Jal, Jalisco; Mex, Estado de México; Mich, Michoacán; Mor, Morelos; Nay, Nayarit; NL, Nuevo León; Oaxaca, Oaxaca; Pue, Puebla; Qro, Querétaro; Q_Roo, Quintana Roo; SLP, San Luis Potosí; Sin, Sinaloa; Son, Sonora; Tab, Tabasco; Tamps, Tamaulipas; Tlax, Tlaxcala; Ver, Veracruz; Yuc, Yucatán; Zac, Zacatecas (https://repositoriodocumental.ine.mx)

Table 2.

Occupational activities of patients with sporotrichosis

| Activities | Number of cases (n = 2764) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Student | 682 | 24.67 |

| Farmer | 636 | 23.01 |

| Housewife | 550 | 19.89 |

| Employee | 87 | 3.14 |

| Builder | 40 | 1.44 |

| Merchant | 31 | 1.12 |

| Gardener | 28 | 1.01 |

| Carpenter | 14 | 0.50 |

| Professional | 13 | 0.47 |

| Mechanic | 8 | 0.28 |

| Florist | 5 | 0.18 |

| Painter | 5 | 0.18 |

| Poultry man | 3 | 0.10 |

| Railway man | 1 | 0.03 |

| Indigent | 1 | 0.03 |

| Undetermined | 660 | 23.87 |

Finally, the revision evidenced that the most frequently employed treatment for sporotrichosis in Mexico is potassium iodide, even though the treatment of choice (itraconazole, terbinafine, amphotericin B, and others) mainly depends on the clinical form of the disease, the host’s immunological status, and the species of Sporothrix involved (Table 1).

Discussion

Sporotrichosis is considered one of the most frequent subcutaneous mycoses in Mexico. For a long time, it ranked second after mycetoma, but most of the cases reported for mycetoma are caused by Nocardia brasiliensis and not by fungal species [56].

Despite the significance of this mycosis in Mexico, public information about sporotrichosis is scarce, and it is not considered a reportable disease according to the Mexican epidemiological national system, the “Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica” [57].

Several studies consider lymphocutaneous and fixed sporotrichosis as the most frequent forms. The results of this review showed that the lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is the most frequent form in Mexico. The possibility that the immune system of each individual, or the species or strain of Sporothrix is related to the clinical presentation is a hypothesis that is still under discussion and study [13].

Regarding the prevalence by gender or age, our results show that the most affected age group is between 0 to 15 years. These results are in accordance with those obtained in a retrospective study conducted by Ramírez-Soto et al. [58] in Peru, which showed that 62% of the cases of sporotrichosis involved children under 14 years of age. Our results are also consistent with the findings from another epidemiology study done in Venezuela, where 34.5% of the sporotrichosis cases diagnosed included patients aged < 15 years [59]. However, the infection depends on the exposure to the fungus, and it is more related to specific occupational and recreational activities in each country. As observed in this review, the highest frequency of the disease was recorded in students, possibly due to their participation in outdoor recreational activities, during which they may suffer from trauma involving material contaminated by the fungus. In India and Japan, there is a higher prevalence of sporotrichosis in females, due to their role in agricultural activities [60]. Likewise, in Brazil, females are most frequently infected, either by zoonotic transmission or by trauma with thorns or bushes [61, 62]. On the other hand, in South Africa, the incidence rate in males is higher than that in females, with a 3:1 ratio, because males participate more frequently in outdoor activities and activities related to mining [63]. Lastly, in Asian countries, such as China and India, sporotrichosis is more common in females than in males [64].

In this review, most of the cases did not offer information about the source of infection. A few cases, in which this data was reported, were attributed to skin trauma with plant sticks, cat scratches, bites and scratches from squirrels, rat bites, trauma with debris, and spider bites. In the 40 studies analyzed, the most frequently reported source of infection was skin trauma with plant sticks (Table 1). It is worth mentioning that most of the areas where sporotrichosis cases occur are temperate, forested mountainous areas, with altitudes of approximately ± 2000 m.a.s.l. and summer rains. According to a meta-analysis performed by Ramirez-Soto et al. [58], Sporothrix spp. have specific ecological niches within endemic areas, and they grow in soils between 6.6 and 28.84 °C, and a relative humidity between 37.5 and 99.06%.

Concerning the diagnosis of sporotrichosis, phenotypic identification requires 5 to 7 days for culture growth and an additional 10 to 21 days for the physiological test [14]. In Mexico, paraclinical diagnosis of sporotrichosis is mainly carried out using conventional methods (sample culture, isolation of the etiologic agent, macro- and micromorphology, histopathology, and ST); thus, most of the records used for this review considered S. schenckii as the only etiological agent.

Immunodiagnostic methods have emerged as an alternative for the diagnosis of sporotrichosis. At first, precipitation and agglutination methods were used [65], but recently, immunoenzymatic assays have been considered new options [66, 67]. These tests are based on the use of antigens obtained from epitopes located on the surface of the Sporothrix cell wall, related to N- and O-linked oligosaccharides of peptidorhamnomannan [68, 69], where the O-linked pentasaccharide has been the primary epitope identified in the peptidorhamnomannan fraction [69]. Although purified antigens have been obtained for serological tests, they have significant limitations, such as low reproducibility and cross-reactivity. Until now, no immunological method has allowed for the identification of Sporothrix at the species level. Another immunological method widely used in epidemiological studies is the skin test (ST) with sporotrichin. This test determines if the patient has been in contact with the etiologic agent [70].

In recent years (since 2014), several researchers have used molecular methods to identify Sporothrix species [53, 71–73]. The most informative loci used for species recognition are located in regions encoding proteins such as calmodulin [74, 75], beta-tubulin [74, 76, 77], the Translation Elongation Factor [4, 64, 77], and the “fungal barcoding” regions (the ribosomal internal transcribed spacers) [78, 79]. Several molecular techniques, as the nested PCR [80, 81]; the Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [82]; the Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) [83]; the Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [84]; the Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) [85], and the Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) [86], have been used successfully. However, the end-point PCR and the real-time multiplex PCR, using fluorescent probes to identify S. globosa, S. schenckii, and S. brasiliensis, predominate [87].

Molecular tools have shown that Sporothrix is a complex fungus formed by phylogenetically related cryptic species, some of them considered of medical relevance, such as S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii sensu stricto, S. globosa, S. mexicana, S. luriei, and S. pallida [6, 88]. New evidence derived from a population genetic analysis of Mexican native isolates has shed light on an indeterminate clade within S. schenckii, which is the species involved in most of the sporotrichosis cases in Mexico [72]. As for S. globose and S. schenckii sensu lato and sensu stricto, they have a worldwide distribution [5]. In Asian countries, S. globosa is the predominant endemic species, with a prevalence of 99.3% [64], while in Brazil, S. brasiliensis has displaced S. schenckii as the most prevalent species [89].

In vitro studies have shown that Sporothrix species differ in virulence and antifungal susceptibility [75, 90], suggesting that the combination of different antifungals can generate a favorable response [91]. Potassium iodide and/or itraconazole (ITC) are the first-line treatments for fixed cutaneous and lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis [92]. Terbinafine has been considered the second-line treatment for lymphocutaneous and cutaneous sporotrichosis, in addition to being an excellent therapeutic option for patients with contraindications to the use of itraconazole or potassium iodide [6, 93]. Amphotericin B is used in the disseminated, systemic, pulmonary, and osteoarticular forms [92, 94]. In pregnant or lactating women with fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis, the use of local thermotherapy (42–43 °C) is recommended, due to the thermolability of the fungus, and amphotericin B is recommended in severe cases. Immunosuppressed patients generally require life-long suppressive therapy [95]. The duration and treatment are based on the “Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Sporotrichosis: 2007 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America” [94].

Conclusions

In Mexico, sporotrichosis has proven to be one of the most frequent subcutaneous mycoses. This study showed that the states with the highest number of cases are Jalisco, Mexico City, Puebla, Guerrero, and Guanajuato. The highest incidence of cases is reported in males, in the ≥ 0–15 age range, showing a lymphocutaneous clinical presentation, and for whom plant traumatisms is identified as the main source of infection. The commonly identified species were S. schenckii and S. globosa. The most frequently used treatment for sporotrichosis is potassium iodide. We emphasize that this is the first retrospective study in Mexico that has done an analysis of sporotrichosis’ epidemiology, geographic distribution, and diagnosis reported between 1914 and 2019. This knowledge could be used to aid in the adoption of strategic public health policies aimed at controlling epidemics.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support of Hortensia Navarro Barranco.

Funding

The authors received financial support from the División de Investigación, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for the different projects involved in this revision.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.López-Romero E, Reyes-Montes MR, Pérez-Torres A, Ruiz-Baca E, Villagómez-Castro JC, Mora-Montes HM, Flores-Carreón A, Toriello C. Sporothrix schenckii complex and sporotrichosis, an emerging health problem. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:85–102. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigues AM, Bagagli E, de Camargo ZP, Bosco Sde M. Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto isolated from soil in an armadillo’s burrow. Mycopathologia. 2014;177:199–206. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Sporothrix species causing outbreaks in animals and humans driven by animal-animal transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(7):e1005638. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigues AM, de Melo TM, de Hoog GS, Schubach TM, Pereira SA, Fernandes GF, Bezerra LM, Felipe MS, de Camargo ZP. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a high prevalence of Sporothrix brasiliensis in feline sporotrichosis outbreaks. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakrabarti A, Bonifaz A, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Mochizuki T, Li S. Global epidemiology of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2015;53:3–14. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myu062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orofino-Costa R, Macedo PM, Rodrigues AM, Bernardes-Engemann AR. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:606–620. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.2017279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aung AK, Teh BM, McGrath C, Thompson PJ. Pulmonary sporotrichosis: case series and systematic analysis of literature on clinico-radiological patterns and management outcomes. Med Mycol. 2013;51:534–544. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.751643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Queiroz-Telles F, Buccheri R, Benard G. (2019) Sporotrichosis in immunocompromised hosts. J Fungi (Basel) 5(1):8. 10.3390/jof5010008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Téllez MD, Batista-Duharte A, Portuondo D, Quinello C, Bonne-Hernández R, Carlos IZ. Sporothrix schenckii complex biology: environment and fungal pathogenicity. Microbiology. 2014;160:2352–2365. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.081794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayorga-Rodríguez J, Mayorga-Garibaldi JL, Muñoz-Estrada VF, De León Ramírez RM. Esporotricosis: serie de 1,134 casos en una zona endémica de México. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 2019;47:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M, Lopes Colombo A, Tobón A, Restrepo A. Mycoses of implantation in Latin America: an overview of epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2011;49:225–236. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.539631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A (2018) Nodular lymphangitis (Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections). Clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel) 4(2):56. 10.3390/jof4020056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Conceicao-Silva F, Morgado FN (2018) Immunopathogenesis of human sporotrichosis: what we already know. J Fungi (Basel) 4(3):89. 10.3390/jof4030089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Diagnosis and treatment of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis: what are the options? Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2013;7:252–259. doi: 10.1007/s12281-013-0140-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miranda LH, Conceicao-Silva F, Quintella LP, Kuraiem BP, Pereira SA, Schubach TM. Feline sporotrichosis: histopathological profile of cutaneous lesions and their correlation with clinical presentation. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;36:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes-Bezerra LM, Schubach A, Costa RO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2006;78:293–308. doi: 10.1590/S0001-37652006000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gayón JP (1914) Un caso de esporotricosis. Gac Méd Mex Tomo IX: 18–20

- 18.Latapi F. Esporotricosis infantil. Nota clínica. Estudio de un caso. Prensa Med Mex. 1950;15:259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavalle P (1980) Esporotricosis. In: Desarrollo y estado actual de la Micología Médica en México. Simposio Syntex, Instituto Syntex edit., México, pp. 115–38

- 20.Mayorga Rodríguez J, Barba-Rubio J, Estrada VF, Cortés A, García-Vargas A, Magaña-Camarena I. Esporotricosis en el estado de Jalisco, estudio clínico-epidemiológico (1960-1996) Dermatol Rev Mex. 1997;41:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinosa-Texis A, Hernández-Hernández F, Lavalle P, Barba-Rubio J, López-Martínez R. Estudio de 50 pacientes con esporotricosis. Evaluación clínica y de laboratorio. Gac Méd Méx. 2001;137:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padilla Desgarennes MC, Orozco La Roche JE. Cuerpos asteroides en el examen directo de un paciente con esporotricosis linfangítica. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2000;9:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padilla Desgarennes MC, Saucedo Rangel AP. Esporotricosis de doble inoculación. Comunicación de un caso. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2001;10:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padilla Desgarennes MC, Zuloeta Espinosa de los Monteros E, Santa Coloma JN. Esporotricosis linfagítica. Presentación de un caso. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2002;11:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padilla Desgarennes MC, Santa Coloma JN, Zuloeta Espinosa de los Monteros EI, Collado Fermín K. Esporotricosis cutánea fija. Presentación de un caso. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2002;11:122–125. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vega-Morquecho O, Bonifaz A, Blancas González F, Mercadillo Pérez P. Esporotricosis cutáneo-hematógena. Rev Med Hosp Gen Mex. 2002;65:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padilla Desgarennes MC, Medina Castillo DE, Cortés Lozano N. Esporotricosis en edad pediátrica: experiencia en el Centro Dermatológico Pascua. Piel. 2004;19:359–363. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Méndez-Tovar LJ, Anides Fonseca E, Peña-González G, Manzano Gayosso P, López Martínez R, Hernández Hernández F, Almeida-Arvizu VM. Esporotricosis cutánea fija incógnita. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2004;21:150–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poletti ED, Michel JA, Arenas R, Medina LA, Arce Martínez FJ. Esporotricosis infantil: otro simulador clínico. Informe de cuatro casos. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2004;48:101–105. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrada-Bravo T. Esporotricosis facial en los niños: diagnóstico clínico y de laboratorio, tratamiento y revisión. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2005;62:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macotela-Ruiz E, Nochebuena-Ramos E. Esporotricosis en algunas comunidades rurales de la Sierra Norte de Puebla. Informe de 55 casos (septiembre 1995-Diciembre 2005) Gac Méd Méx. 2006;142:377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muñoz-Estrada VF, Lizárraga-Gutiérrez CL, Gómez Llanos NM. Esporotricosis linfangítica. Reporte de un caso. Bol Med UAS. 2006;12:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carrada-Bravo T. Esporotricosis pulmonar cavitada: diagnóstico y tratamiento. Med Int Mex. 2006;22:457–461. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Padilla Desgarennes MC, Siordia Zambrano SA, Santa CJN. Esporotricosis con involución espontánea. Caso clínico. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2007;51:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padilla Desgarennes MC, Navarrete Franco G, Siu Moguel CM. Esporotricosis linfagítica con nódulos satélites en el chancro de inoculación. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2008;17:54–57. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arenas R, Miller D, Campos-Macias P. Epidemiological data and molecular characterization (mtDNA) of Sporothrix schenckii in 13 cases from Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:177–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bada del Moral M, Arenas R, Ruiz Esmenjaud J. Esporotricosis en Veracruz. Estudio de cinco casos. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2007;51:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonifaz A, Saúl A, Paredes-Solis V, Fierro L, Rosales A, Palacios C, Araiza J. Sporotrichosis in childhood: clinical and therapeutic experience in 25 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:369–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chávez Fuentes I, de la Cabada BJ, Uribe Jiménez EE, Gómez Salcedo HJ, Velasco J, Rodríguez F, Arias Amaral J. Esporotricosis sistémica: comunicación de un caso y revisión bibliográfica. Med Int Mex. 2007;23:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fonseca-Reyes S, López Maldonado FJ, Miranda-Ackerman RC, Vélez-Gómez E, Álvarez-Iñiguez P, Velarde-Rivera FA, Ascensio-Esparza EP. Extracutaneous sporotrichosis in a patient with liver cirrosis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2007;24:41–43. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(07)70010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munguía Pérez R, Romo Lozano Y, Castañeda Roldán E, Velázquez Escobar MC, Espinosa-Texis A. Epidemiología de la esporotricosis en el municipio de Huauchinango, Puebla. Enferm Infecc Microbiol. 2007;27:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 42.García-Vargas A, Mayorga J, Soto Ortiz A, Barba Gómez JF. Esporotricosis en niños. Estudio de 133 casos en el Instituto Dermatológico de Jalisco “Dr. José Barba Rubio”. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 2008;36:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barba-Borrego JA, Mayorga J, Tarango-Martínez VM. Esporotricosis linfagítica bilateral y simultánea. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2009;26:247–249. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roldán-Marín R, Contreras-Ruiz J, Arenas R, Vazquez-del-Mercado E, Toussaint-Caire S, Vega-Memije ME. Fixed sporotrichosis as a cause of a chronic ulcer on the knee. Int Wound J. 2009;6:63–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutierrez-Morales JL, Domínguez Romero R, Morales Esponda M, Rossiere Echazaleta NL, Reyes Bonifant G, Santos Ramírez A. Esporotricosis micematoide con invasión a médula espinal. Rev Mex Neuroci. 2011;12:50–54. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romero-Cabello R, Bonifaz A, Romero-Feregrino R, Javier Sánchez C, Linares Y, Tay Zavala J, Calderón Romero L, Romero-Feregrino R, Sánchez Vega JT (2011) Disseminated sporotrichosis. BMJ Case Rep. 10.1136/bcr.10.2010.3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Rojas-Padilla R, Pastrana R, Toledo M, Valencia A, Mena C, Bonifaz A. Esporotricosis cutánea linfangítica por mordedura de araña. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2013;57:479–484. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chávez-López G, Estrada-Castañón R, Estrada-Chávez G, Vega-Memije ME, Moreno-Coutiño G. Esporotricosis cutánea diseminada: un caso de la región de La Montaña del estado de Guerrero, México. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2015;59:228–232. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palma-Ramos A, Castrillón-Rivera LE, Fernández-López SE, Paredes-Rojas A, Castañeda-Sánchez JI, Padilla-Desgarennes MC, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas-Guzmán R. Lactoferrina en 11 pacientes diagnosticados con esporotricosis cutánea. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2015;59:280–287. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cotino Sánchez A, Torres-Alvarez B, Gurrola Morales T, Méndez Martínez S, Saucedo Gárate M, Castanedo-Cazares JP. Mycosis fungoides-like lesions in a patient with diffuse cutaneous sporotrichosis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2015;32:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Estrada-Castañón R, Chávez-López G, Estrada-Chávez G, Bonifaz A. Report of 73 cases of cutaneous sporotrichosis in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:907–909. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rojas OC, Bonifaz A, Campos C, Treviño-Rangel RJ, González-Álvarez R, González GM (2018) Molecular identification, antifungal susceptibility, and geographic origin of clinical strains of Sporothrix schenckii complex in Mexico. J Fungi (Basel) 4(3):86. 10.3390/jof4030086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Rangel-Gamboa L, Martinez-Hernandez F, Maravilla P, Flisser A. A population genetics analysis in clinical isolates of Sporothrix schenckii based on calmodulin and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase partial gene sequences. Mycoses. 2018;61:383–392. doi: 10.1111/myc.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ochoa-Reyes J, Ramos-Martínez E, Treviño-Rangel R, González GM, Bonifaz A. Esporotricosis del pabellón auricular. Comunicación de un caso atípico simulando una celulitis bacteriana. Rev Chil Infectol. 2018;35:83–87. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182018000100083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puebla-Miranda M, Vásquez-Ramírez M, González-Ibarra M, Torres-López IH. Esporotricosis. Reporte de un caso ocupacional. Rev Hosp Jua Mex. 2018;85:246–250. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bonifaz A. Esporotricosis. In: Méndez-Cervantes F, editor. Micología médica básica, 1st edn. México: Mendez-Cervantes; 1990. pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diario Oficial de la Federación DOF 2013 NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-017-SSA2-2012

- 58.Ramírez-Soto MC, Aguilar-Ancori EG, Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Ecological determinants of sporotrichosis etiological agents. J Fungi (Basel) 2018;4:95. doi: 10.3390/jof4030095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mata-Essayag S, Delgado A, Colella MT, Landaeta-Nezer ME, Rosello A, Perez de Salazar C, Olaizola C, Hartung C, Magaldi S, Velasquez E. Epidemiology of sporotrichosis in Venezuela. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:974–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhutia PY, Gurung S, Yegneswaran PP, Pradhan J, Pradhan U, Peggy T, Pradhan PK, Bhutia CD. A case series and review of sporotrichosis in Sikkim. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:603–608. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barros MB, Schubach AO, Schubach TM, Wanke B, Lambert-Passos SR. An epidemic of sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: epidemiological aspects of a series of cases. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:1192–1196. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807009727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, Freitas DF, do Valle AC, Zancope-Oliveira RM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vismer HF, Hull PR. Prevalence, epidemiology and geographical distribution of Sporothrix schenckii infections in Gauteng, South Africa. Mycopathologia. 1997;137:137–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1006830131173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Y, Hagen F, Stielow B, Rodrigues AM, Samerpitak K, Zhou X, Feng P, Yang L, Chen M, Deng S, Li S, Liao W, Li R, Li F, Meis JF, Guarro J, Teixeira M, Al-Zahrani HS, Pires de Camargo Z, Zhang L, de Hoog GS. Phylogeography and evolutionary patterns in Sporothrix spanning more than 14 000 human and animal case reports. Persoonia. 2015;35:1–20. doi: 10.3767/003158515X687416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Albornoz MB, Villanueva E, de Torres ED. Application of immunoprecipitation techniques to the diagnosis of cutaneous and extracutaneous forms of sporotrichosis. Mycopathologia. 1984;85:177–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00440950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Almeida-Paes R, Pimenta MA, Monteiro PCF, Nosanchuk JD, Zancope-Oliveira RM (2007) Immunoglobulins G, M, and A against Sporothrix schenckii exoantigens in patients with sporotrichosis before and during treatment with itraconazole. Clin Vaccine Immunol 14:1149–1157. 10.1128/CVI.00149-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Bernardes-Engemann AR, Costa RC, Miguens BR, Penha CV, Neves E, Pereira BA, Dias CM, Gutierrez MC, Schubach A, Oliveira-Neto MP, Lazéra M, Lopes-Becerra LM. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the serodi-agnosis of several clinical forms of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2005;43:487–493. doi: 10.1080/13693780400019909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Travassos LR. Antigenic structures of Sporothrix schenckii. Immunol Ser. 1989;47:193–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lopes-Alves L, Travassos LR, Previato JO, Mendonca-Previato L. Novel antigenic determinants from peptidorhamnomannans of Sporothrix schenckii. Glycobiology. 1994;4:281–288. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arenas R, Sánchez-Cardenas CD, Ramirez-Hobak L, Ruíz Arriaga LF, Vega Memije ME (2018) Sporotrichosis: from KOH to molecular biology. J Fungi (Basel) 4(2):62. 10.3390/jof4020062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Estrada-Bárcenas DA, Vite-Garín T, Navarro-Barranco H, de la Torre-Arciniega R, Pérez-Mejía A, Rodríguez-Arellanes G, Ramire JA, Sahaza JH, Taylor ML, Toriello C. Genetic diversity of Histoplasma and Sporothrix complexes based on sequences of their ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 regions from the BOLD System. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014;31:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Toriello C, Brunner-Mendoza C, Navarro-Barranco H, Parra-Jaramillo LS (2017)Phylogenetic analysis of clinical and environmental isolates of the Sporothrix complex. 2nd International Meeting on Sporothrix and sporotrichosis. Guanajuato, GT, Mexico. September 11–12

- 73.Rojas OC, Bonifaz A, Campos C, Treviño-Rangel RJ, González-Álvarez R, González GM. (2018) Molecular identification, antifungal susceptibility, and geographic origin of clinical strains of Sporothrix schenckii complex in Mexico. J Fungi (Basel) 4(3):86. 10.3390/jof4030086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Marimon R, Gené J, Cano J, Trilles L, Dos Santos LM, Guarro J. Molecular phylogeny of Sporothrix schenckii. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3251–3256. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00081-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marimon R, Cano J, Gené J, Sutton DA, Kawasaki M, Guarro J. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3198–3206. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00808-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Meyer EM, de Beer ZW, Summerbell RC, Moharram AM, de Hoog GS, Vismer HF, Wingfield MJ. Taxonomy and phylogeny of new wood- and soil-inhabiting Sporothrix species in the Ophiostoma stenoceras-Sporothrix schenckii complex. Mycologia. 2008;100:647–661. doi: 10.3852/07-157R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP (2015) Molecular diagnosis of pathogenic Sporothrix species. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0004190. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Beer ZW, Harrington TC, Vismer HF, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2003) Phylogeny of the Ophiostoma stenoceras–Sporothrix schenckii complex. Mycologia 95:434–441 [PubMed]

- 79.Liu X, Zhang Z, Hou B, Wang D, Sun T, Li F, Wang H, Han S. Rapid identification of Sporothrix schenckii in biopsy tissue by PCR. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1491–1497. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12030./S0001-37652006000200009x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hu S, Chung WH, Hung SI, Ho HC, Wang ZW, Chen CH, Lu SC, Kuo TT, Hong HS. Detection of Sporothrix schenckii in clinical samples by a nested PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1414–1418. doi: 10.1128/jcm.41.4.1414-1418.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu TH, Lin JP, Gao XH, Wei H, Liao W, Chen HD. Identification of Sporothrix schenckii of various mtDNA types by nested PCR assay. Med Mycol. 2010;48:161–165. doi: 10.3109/13693780903117481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oliveira MME, Sampaio P, Almeida-Paes R, Pais C, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Zancope-Oliveira RM. Rapid identification of Sporothrix species by T3B fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2159–2162. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00450-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kawasaki M, Anzawa K, Mochizuki T, Ishizaki H. New strain typing method with Sporothrix schenckii using mitochondrial DNA and polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) technique. J Dermatol. 2012;39:362–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mesa-Arango AC, Reyes-Montes MR, Perez-Mejia A, Navarro-Barranco H, Souza V, Zuniga G, Toriello C. Phenotyping and genotyping of Sporothrix schenckii isolates according to geographic origin and clinical form of sporotrichosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3004–3011. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3004-3011.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Neyra E, Fonteyne PA, Swinne D, Fauche F, Bustamante B, Nolard N. Epidemiologyof human sporotrichosis investigated by amplified fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1348–1352. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1348-1352.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodrigues AM, Najafzadeh MJ, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Rapid identification of emerging human-pathogenic Sporothrix species with rolling circle amplification. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1385. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang M, Li F, Li R, Gong J, Zhao F (2019) Fast diagnosis of sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix globosa, Sporothrix schenckii, and Sporothrix brasiliensis based on multiplex real-time PCR. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007219. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Alba-Fierro CA, Pérez-Torres A, Toriello C, Romo-Lozano Y, López-Romero E, Ruiz-Baca E (2016) Molecular components of the Sporothrix schenckii complex that induce immune response. Curr Microbiol 73:292–300 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.De Araujo ML, Rodrigues AM, Fernandes GF, de Camargo ZP, de Hoog GS. Human sporotrichosis beyond the epidemic front reveals classical transmission types in Espírito Santo, Brazil. Mycoses. 2015;58:485–490. doi: 10.1111/myc.12346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arrillaga-Moncrieff I, Capilla J, Mayayo E, Marimon R, Marine M, Gene J, Vano J, Guarro J. Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:651–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ottonelli SCD, Magagnin CM, Castrillón MR, Mendes SDC, Heidrich D, Valente P, Scroferneker ML. Antifungal susceptibilities and identification of species of the Sporothrix schenckii complex isolated in Brazil. Med Mycol. 2014;52:56–64. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2013.818726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.García Carnero LC, Lozoya Pérez NE, González Hernández SE, Martínez Álvarez JA (2018) Immunity and treatment of sporotrichosis. J Fungi (Basel) 4:100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Meinerz ARM, Nascente PDS, Schuch LFD, Cleff MB, Santin R, Brum CDS, Nobre MDO, Meireles MCA, Mello JRDB. Suscetibilidade in vitro de isolados de Sporothrix schenckii frente à terbinafina e itraconazol. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40:60–62. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822007000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kauffman CA, Bustamante B, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1255–1265. doi: 10.1086/522765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mahajan VK. Sporotrichosis: an overview and therapeutic options. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2014/272376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]