Abstract

In this work, we isolated four Cd-tolerant endophytic bacteria from Typha latifolia roots that grow at a Cd-contaminated site. Bacterial isolates GRC065, GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140 were identified as Pseudomonas rhodesiae. These bacterial isolates tolerate cadmium and have abilities for phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, indole acetic acid (IAA) synthesis, and ACC deaminase activity, suggesting that they are plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Bacterial inoculation in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings showed that P. rhodesiae strains increase total fresh weight and number of lateral roots concerning non-inoculated plants. These results indicated that P. rhodesiae strains promote A. thaliana seedlings growth by modifying the root system. On the other hand, in A. thaliana seedlings exposed to 2.5 mg/l of Cd, P. rhodesiae strains increased the number and density of lateral roots concerning non-inoculated plants, indicating that they modify the root architecture of A. thaliana seedlings exposed to cadmium. The results showed that P. rhodesiae strains promote the development of lateral roots in A. thaliana seedlings cultivated in both conditions, with and without cadmium. These results suggest that P. rhodesiae strains could exert a similar role inside the roots of T. latifolia that grow in the Cd-contaminated environment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-020-00408-9.

Keywords: Endophytes, Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, Pseudomonas rhodesiae, Cadmium tolerance, Typha latifolia

Introduction

Typha genus is commonly known as cattail and includes nine species, T. minima, T. elephantine, T. angustifolia, T. domingensis, T. capensis, T. latifolia, T. shuttleworthii, T. orientalis, and T. laxmannii, widely distributed throughout the world, except in Antarctica [1]. Typha species are invasive plants that inhabit many aquatic ecosystems due to their rapid growth rate and high capacity to adapt to nutrient deprivation, flood, salinity, and drought [2]. Typha spp. are used in phytoremediation strategies due to its ability to grow in heavy metal-contaminated environments, remove heavy metals from sediments, and accumulate them in their tissues [3]. Thus, Typha species have been employed in artificial wetlands to treat industrial or domestic wastewater [4].

Plants used in phytoremediation establish interactions with rhizospheric microorganisms to resist the heavy metal toxicity [5]. Among these microorganisms include plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs), which comprise a diversity of bacterial genera that colonize the rhizosphere and thus contribute to plant adaptation to the environment conditions [6]. PGPRs promote plant growth through biochemical activities such as phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, indole acetic acid (IAA) synthesis, ACC deaminase activity, and nitrogen fixation [7]. In Spartina densiflora, PGPRs promote the plant growth, reduce metallic stress by As, Cu, Pb, and Zn, and increase the accumulation of these metals in plant roots [8, 9]. The inoculation of Pseudomonas spp. and Rhizobium sullae in the host plant Sulla coronaria improves plant growth under Cd stress conditions [10]. Thus, PGPRs promote the growth of host plants in contaminated sites and improve phytoremediation processes [7].

Some studies have explored the microbial diversity in the roots of Typha plants that grow in wetlands to treat domestic wastewater. Li et al. [11] identified endophytic bacteria from inside of T. angustifolia roots by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene. They suggested that bacteria improve the plant growth in wetlands and remove nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic matter from domestic wastewater [11]. Although these bacteria improve the phytoremediation of eutrophic water bodies, there are no available bacterial isolates for biotechnological application.

Moreover, Ghosh et al. [12] isolated three iron-oxidizing bacteria Paenibacillus cookii JGR8, Pseudomonas jaduguda JGR2, and Bacillus megaterium JGR9 from the rhizosphere of T. angustifolia that grow in a uranium mine tailing contaminated with iron. These bacterial isolates showed biochemical activities related to plant growth promotion, such as siderophore production, IAA synthesis, and phosphate-solubilizing capacity. Bacterial inoculation in the host plant showed that P. cookii JGR8 increased the height of T. angustifolia compared to non-inoculated plants, whereas B. megaterium JGR9 and P. jaduguda JGR2 did not promote the plant growth [12]. Nevertheless, the role of these bacteria in phytoremediation is unknown.

Furthermore, endophytic bacteria from the T. angustifolia roots collected from the uranium mine tailing contaminated with iron have been reported [13]. Ten isolates were characterized according to the plant growth-promoting abilities and inoculated to the host and non-host plants, T. angustifolia and rice, respectively. The results showed that bacterial consortium promotes the growth of both T. angustifolia and rice [13]. Although bacteria exert PGPR activities like auxin synthesis, siderophore production, and nitrogen fixation, their ability to tolerate heavy metal remains poorly understood.

To date, there are no reports on PGPRs associated with the T. latifolia roots and their contribution to the plant growth. Even more, bacteria associated with T. latifolia roots growing in heavy metal-contaminated environments and their contribution to the plant’s tolerance to heavy metal are unknown. Therefore, in this study, endophytic bacteria were isolated from T. latifolia roots growing at a site contaminated with cadmium (Cd). The bacterial screening was based on Cd tolerance, and the most Cd-tolerant isolates were selected to assess activities related to plant growth promotion. Furthermore, bacteria contribution to plant growth and Cd tolerance was demonstrated in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings grown in the absence and presence of Cd.

Material and methods

Plant material collection and Cd content analysis

Samples were collected from a site where Cd contamination has been previously reported in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, at coordinates 22° 09′ 07.0″ N and 101° 02′ 14.2″ W (22.151752–101.037316) [14]. Twenty plants and 100 g of surrounding soil were taken and transported to the laboratory in a plastic bag, in December 2014.

Roots were separated from the plants and washed exhaustively in tap water to eliminate the soil. They were then rinsed with deionized water and immersed in EDTA 0.01 M for 10 min to remove the heavy metal adsorbed on the root surface. The cleaned roots were dried and ground to determine Cd content. Briefly, 10 g of powdered roots was digested in a mixture of HNO3 and H2O2 [15]. The digestion product was filtered, and the clean sample was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES; Varian 730-ES, USA). Likewise, the soil samples obtained from the twenty plants were mixed, dried, and powdered. Then, 10 g of dry soil was digested in a mixture of HNO3 and HCl, according to the standardized procedures of LANBAMA, IPICYT (SLP, Mexico). The product of the digestion was filtered and analyzed to determine the Cd content, as described above. All analyses were performed in triplicate. Results of quantitation were used to calculate the bioconcentration factor (BCF) using the formula:

where Cd soil and Cd roots are respectively the concentrations (mg/kg of dry weight) of Cd in soil and roots of T. latifolia.

Isolation of endophytic bacteria from T. latifolia roots

Root samples were washed in running water to eliminate the attached soil particles. For surface sterilization, the clean roots were immersed in a mixture of absolute ethanol and 30% H2O2 (1:1) for 20 min and then rinsed three times with sterile distilled water for 5 min. To confirm that the disinfection process was successful, 100 μl aliquots of the last rinse was inoculated in Luria Bertani (LB) agar medium and incubated at 28 °C for 72 h [16]. After incubation, the root samples with the absence of bacterial growth on media were considered to be successfully surface disinfected and then used for endophytic bacteria isolation. One gram of surface-sterilized roots was homogenized with 9 ml sterile distilled water. Tenfold dilutions were prepared, and 100 μl aliquots of dilutions was inoculated in LB agar at fifth strength supplemented with CdCl2 0.04 mM (Fermont, Mexico). After incubation at 28 °C for 48 h, bacterial colonies were picked and streaked in a new LB agar supplemented with CdCl2 0.04 mM and incubated at similar conditions. This procedure was replicated three times to eliminate false positives.

Cd tolerance of endophytic bacteria

First, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of Cd was determined by dilution of a Cd stock solution in LB agar. Bacterial isolates were inoculated in LB agar supplemented with different concentrations of Cd (0.03, 0.07, 0.14, 0.28, 0.56, 1.11, 2.22, 4.45, and 8.90 mM of CdCl2) and incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. After incubation, bacterial growth was examined visually, and the MIC was considered the minimum Cd concentration that inhibits bacterial growth. LB agar without metal was used as growth control [17].

Moreover, the maximum tolerable concentration (MTC) to Cd was determined using fixed CdCl2 concentrations as described by Ndeddy Aka and Babalola [17] with modifications. Briefly, a 44.5 mM CdCl2 sterile solution was diluted in 150 μl of LB broth to a final concentration of 1.78, 3.56, 4.45, 5.34, 7.12, or 8.90 mM of CdCl2. LB broth was inoculated at 1.0% (v/v) with a bacterial suspension of each isolate adjusted to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm. LB broth without Cd was used as growth control. The microplates were incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. After Cd exposure, 2 μl of each well was inoculated in LB agar medium without Cd and incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. The MCT was considered the highest concentration of Cd that does not inhibit bacterial growth.

Molecular analysis of endophytic bacteria

DNA was extracted from bacterial isolates, according to Chen and Kuo [18]. Amplification of 16S rRNA, gyrA, and rpoD genes was carried out by PCR using Platinum PCR SuperMix High Fidelity (Invitrogen, USA) and 10 pmol of each primer (Table S1) [19]. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C, 30 s; 50 °C, 30s; 72 °C, 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR product was sequenced at LANBAMA, IPICYT (SLP, Mexico), and aligned at Blast NCBI to determine similarity in the database. Phylogenetic analysis was performed in MEGA 7, using the maximum parsimony method with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Besides, the czcA gene that belongs to czcCBA transcriptional unit involved in tolerance to Cd, Zn, and Co was amplified by PCR using the primers czcA Fwd and czcA Rev (Table S1) [20]. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C, 30 s; 55 °C, 30s; 72 °C, 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR product (263 bp) was sequenced at LANBAMA, IPICYT (SLP, Mexico), and aligned at Blast NCBI to determine similarity in the database.

Determination of phosphate solubilization activity

Bacterial isolates were grown in NBRIP (National Botanical Research Institute’s Phosphate) agar media containing 0.5% Ca3(PO4)2 as phosphorus source and bromocresol purple as pH indicator [21]. After incubation at 28 °C for 48 h, bacteria that produce a yellow halo around the colony were considered phosphate solubilizers. Bacterial isolates were grown in NBRIP broth pH 7.0 at 28 °C during 120 h to determine phosphate solubilization levels. Later, cells were removed by centrifugation at 2450g for 30 min to obtain cell-free supernatants. The pH of supernatants was measured with pH meter (Jenway 3510 pH meter, UK). Soluble phosphorus quantification was performed as follows. One hundred microliters of cell-free supernatant was mixed with 500 μl of H2SO4 (30%), 500 μl of molybdic solution (5 g/100 ml), and 300 μl of the ANS solution (0.002 g/ml of 4-aminonaphthalene-1-sulphonic acid, 0.12 g/ml of sodium bisulfite, 0.024 g/ml sodium sulfite) and tri-distilled water to a final volume of 10 ml. The mixture was allowed to stand for 30 min, and absorbance read at 880 nm. Soluble phosphorus concentration was calculated using a phosphorus calibration curve [22].

Siderophore production

Bacterial isolates were grown in a Fe-deficient minimal media (MM9) broth at 28 °C for 48 h [23]. Later, cells were removed by centrifugation at 2450g for 30 min to obtain cell-free supernatants. Siderophore production was determined using a Chrome Azurol S (CAS; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution [24]. Briefly, 500 μl cell-free supernatant of each isolate was mixed with 500 μl of the CAS solution (1:1 ratio), homogenized, and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. Reference was prepared, mixing non-inoculated MM9 broth with CAS solution. After incubation, the absorbance of the samples and the reference were measured at 630 nm. Siderophore unit is proportional to the discoloration of the CAS solution and was calculated using the formula:

where Am is the absorbance at 630 nm of the samples and Ar is the absorbance of the reference [23].

Auxin production

To determine indole acetic acid (IAA) production, bacterial isolates were grown in LB broth with 0.1% L-tryptophan (L-Trp; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 28 °C for 48 h [25]. Cell-free supernatants were acidified with HCl 2 N and extracted with ethyl acetate (Karal, purity: 99.85%). The extract was concentrated to dryness in a rotary evaporator R-100 (BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, Switzerland) and resuspended in ethanol (Tedia, purity: >99.0%). Fifty microliters of ethanolic extract was solvent-freed under nitrogen flux. Then, 20 μl of pyridine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 80 μl of N,O-Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) with 1.0% of chlorotrimethylsilane (TMCS; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were added. The mixture was incubated at 85 °C for 25 min. After the reaction, the mixture was cooled at room temperature, and isooctane (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to a final volume of 200 μl. Finally, 100 μl of the clear mix was transferred to a vial and analyzed immediately by gas chromatography (GC model 7890A; Agilent Technologies, USA) coupled to electron impact mass spectrometry (EIMS model 5975; Agilent Technologies, USA). IAA and related compounds produced by bacterial isolates from L-Trp were identified using the software MassHunter Workstation (version B.06.00, Agilent Technologies) and the NIST MS Search database version 2.0 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2008). Determination of the retention time and mass spectra was determined by software AMDIS (http://www.amdis.net/). Quantitation of IAA and related compounds were assessed based on the IAA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) calibration curve obtained in the same conditions.

ACC deaminase detection

Bacterial isolates were inoculated in selective DF minimal medium [26] supplemented with 3 mM of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as the sole nitrogen source and incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. Bacteria that grow in DF-ACC media were considered to have ACC deaminase activity. The presence of the acdS gene encoding ACC deaminase enzyme in the genome of bacterial strains was determined by PCR using oligonucleotides ACC5 and ACC3 (Table S1) [27]. DNA of P. aeruginosa was used as a negative control. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C, 30 s; 51 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplification products (750 bp) were visualized in agarose 1.0%.

Effect of bacterial strains in Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 development

Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 seeds were superficially sterilized in a mixture of 50% sodium hypochlorite with 0.02% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and then were placed on water-agar 0.7% (w/v) and vernalized at 4 °C for 48 h. Later, plates were transferred to the growth chamber and incubated at 28 °C under fluorescent light with a photoperiod 16 h light/8 h dark for 5 days [28]. For plant-bacteria interaction assays, five A. thaliana seedlings after 5 days of germination were transferred to 0.2X Murashige and Skoog (MS Basal Salt Mixture; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) agar medium with sucrose (0.75%) at pH 5.7 with 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) buffer (3.5 mM). Then, 20 μl of the bacterial isolate suspension of 107 CFU/ml in saline solution (0.85% NaCl) was inoculated at 4 cm away from the seedling roots. As a control, the saline solution was tested. Plates were incubated vertically for 10 days at 28 °C, under fluorescent light, and a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h darkness. After incubation, the seedlings were recovered and determined the total fresh weight, the hypocotyls length, the primary root length, and the number of lateral roots. Lateral roots density was calculated using the formula:

Contribution of bacterial isolates to Cd tolerance in A. thaliana Col-0

A dose-response curve was performed to determine the Cd concentration that modifies A. thaliana seedlings growth in MS agar media. Cd concentrations (as CdCl2) used in the experiment reported here were in the range from 0 to 10 mg/l CdCl2. Based on results, the dose 2.5 mg/l of CdCl2 was used in subsequent experiments to determine whether bacteria isolates contribute to Cd tolerance. The bacterial suspension of isolates was inoculated at 4 cm away from the roots of five A. thaliana seedlings placed in MS agar supplemented with 2.5 mg/l of CdCl2. Plates were incubated vertically for 10 days at 28 °C, under fluorescent light, and a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h darkness, and then bacterial isolate effects were determined as described above. Saline solution (0.85% NaCl) without bacteria was used as a control.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software GraphPad Prism Version 5.01. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with Tukey’s method to compare the means between treatments (p < 0.05).

Results

Cadmium content in soil and root tissue of T. latifolia

Initially, the Cd amount in the soil and T. latifolia roots was determined. The results confirmed the presence of this heavy metal in the sampling site and the roots of T. latifolia used in this study. The soil contained 5.65 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW of Cd, whereas the roots 1.82 ± 0.05 mg/kg DW of Cd. The bioconcentration factor (BCF) was calculated to determine the ratio of Cd in roots concerning concentration in surrounding soil [29]. In this study, the BCF of T. latifolia was 0.32, which indicate that T. latifolia takes up Cd from the soil and accumulates it in its roots [29].

Endophytic bacteria of T. latifolia roots tolerate Cd

The screening and isolation of Cd-tolerant endophytic bacteria from T. latifolia roots were performed in the LB agar medium supplemented with 0.04 mM of CdCl2. The results indicated that Cd-tolerant endophytic bacteria colonize the roots of T. latifolia that grow at the Cd-contaminated site. A total of 205 bacterial isolates with the capacity to grow in the presence of Cd were obtained. Furthermore, the MIC was performed to determine the minimum concentration of Cd that prevents bacterial growth. The results showed that Cd inhibits bacterial growth in a concentration-dependent manner, thus indicating that endophytic bacteria have different degrees of Cd tolerance (Table S2). According to the MIC test, we selected the most Cd-tolerant isolates GRC065, GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140 for further characterization.

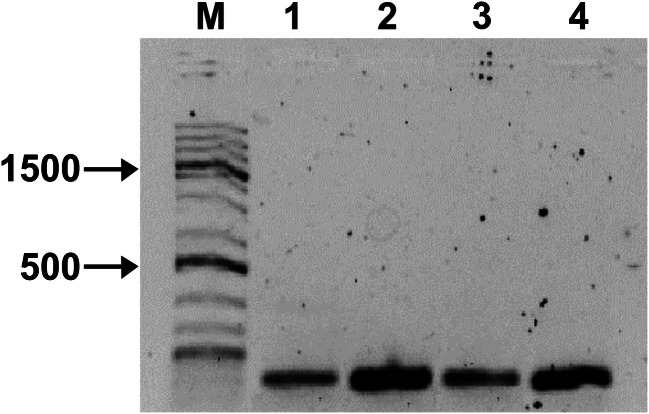

Moreover, bacterial suspensions of GRC065, GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140 isolates were exposed to fixed Cd concentrations (1.78, 3.56, 4.45, 5.34, 7.12, and 8.90 mM of CdCl2) for 48 h to determine the MTC. Results showed that 8.90 mM of CdCl2 affects the viability of all four tested isolates because no colony development was observed in the LB plate (Fig. 1). Concentrations of CdCl2 up to 7.12 mM did not alter the viability of isolates GRC065 and GRC066, which showed growth in LB agar media after exposure to these Cd concentrations. GRC093 and GRC140 remain viable up to levels of 4.45 and 5.34 mM of CdCl2, respectively (Fig. 1). For GRC065 and GRC066, the MTC is 7.12 mM of CdCl2, whereas GRC093 and GRC140 4.45 and 5.34 mM of CdCl2, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Maximum tolerable concentration test. Bacterial growth in LB media after 48 h of Cd exposure

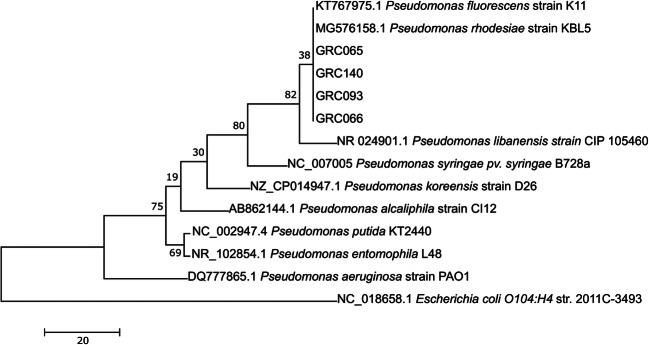

Heavy metal tolerance in bacteria depends on the active flow of metal ions outside the cell. In Gram-negative bacteria, CzcCBA multiproteic system encoded by the czcCBA transcriptional unit is the most studied efflux pump that confers resistance to Cd, Zn, and Co [30]. To determine the presence of czcCBA in the genome of isolates GRC065, GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140, the czcA gene was amplified by PCR. The amplification of a PCR product of the expected size (263 bp) suggested the presence of czcA gene in the genome of the four isolates evaluated (Fig. 2). The Blast searches indicated that the putative czcA sequence (GenBank Accession No. MT646764) has a 100.0% similarity with czcA gene of P. putida KT2440 that encodes a CusA/CzcA family heavy metal efflux RND transporter. Thus, the results suggested that the efflux pump CzcCBA is present in the genome of four isolates and could be involved in Cd tolerance of strains GRC065, GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140.

Fig. 2.

PCR amplification of the czcA gene using genomic DNA from P. rhodesiae GRC065 (1), GRC066 (2), GRC093 (3), and GRC140 (4). Line M, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder

Molecular identification of GRC065, GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140 isolates

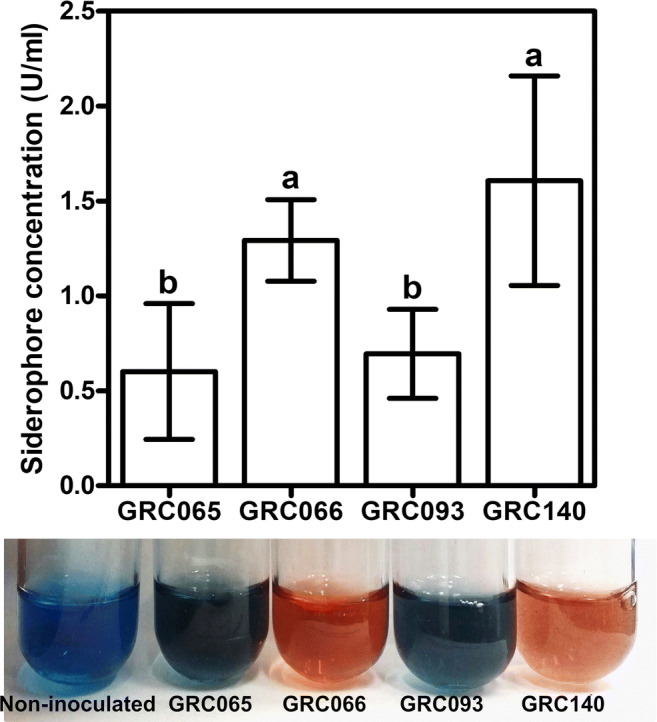

Sequences of the 16S rRNA gene from the isolates GRC065 (GenBank Accession No. MN945309), GRC066 (MN945310), GRC093 (MN945311), and GRC140 (MN945312) were compared with available sequences in the GenBank database. The results indicated that 16S rRNA gene sequences showed 99–100% similarity with sequences of Pseudomonas rhodesiae strains (Table S3). Phylogenetic analysis showed that 16S rRNA gene sequences of endophytic bacterial isolates were grouped in a clade together with 16S rRNA of P. rhodesiae (Fig. 3). In addition, blast analysis of gyrA and rpoD sequences showed 99% similarity with sequences of P. rhodesiae (gyrA, MT646756, MT646757, MT646758, MT646759; rpoD, MT646760, MT646761, MT646762, MT646763), thus confirming that the identity of strains GRC065, GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140 corresponds to P. rhodesiae (Table S3). These strains produce pyoverdine in minimal M9 medium and confirm that bacteria belong to the fluorescents Pseudomonas group (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence of bacterial isolates. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the maximum parsimony method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Numbers on the branches indicate the percentage of 1000 bootstrap samples supporting the branch. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of E. coli was used as an outgroup

P. rhodesiae strains have plant growth-promoting characteristics

Phosphate solubilization assays in NBRIP plates showed that P. rhodesiae strains formed a yellow halo around the colony because of the production of low molecular weight organic acids (Fig. S2a). The acidification of culture media contributes to the bioavailability of phosphorus from Ca3(PO4)2 [31]. At pH close to 5, the predominant species is H2PO4−, a chemical structure that can be assimilated by bacteria. The results showed that P. rhodesiae strains decreased the pH of the culture medium (from 6.85 to 4.73 ± 0.08) (p < 0.05), suggesting that acidification is the mechanism used by P. rhodesiae strains for the assimilation of phosphorus from Ca3(PO4)2 (Table 1). Quantitative analysis of soluble phosphorus in cell-free supernatants of P. rhodesiae strains revealed that bacteria solubilized phosphate in the range from 111.8 ± 5.7 to 136.2 ± 11.3 mg/l of phosphorus from Ca3(PO4)2 (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Compared to the control treatment, the presence of bacteria in the culture medium increased soluble P by 35–65%. However, there were no statistical differences between P. rhodesiae strains in solubilizing P of Ca3(PO4)2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Plant growth-promoting features of P. rhodesiae strains

| Strain | Ca3(PO4)2 solubilization | Auxins | ACC deaminase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | P soluble (mg/l) | IAA (mg/l) | PAA (mg/l) | Growth in DF medium | acdS gene | |

| GRC065 | 4.99 ± 0.05a | 134.9 ± 14.8a | 0.93 ± 0.03a | 0.55 ± 0.06a | ND | ND |

| GRC066 | 4.89 ± 0.07a | 116.9 ± 4.3ab | 1.19 ± 0.05ª | 0.79 ± 0.07a | + | + |

| GRC093 | 4.78 ± 0.10a | 111.8 ± 5.7ab | 1.08 ± 0.17a | 0.60 ± 0.09a | + | + |

| GRC140 | 4.73 ± 0.08ª | 136.2 ± 11.3ª | 1.31 ± 0.13a | 0.81 ± 0.17a | + | + |

| Control | 6.85 ± 0.05b | 82.33 ± 3.11b | ND | ND | ND | ND |

(+) Positive. (ND) Not detected

Results are expressed as media ± SE (n = 6)

Different letters represent means statistically different (p < 0.05)

IAA indole acetic acid, PAA phenylacetic acid

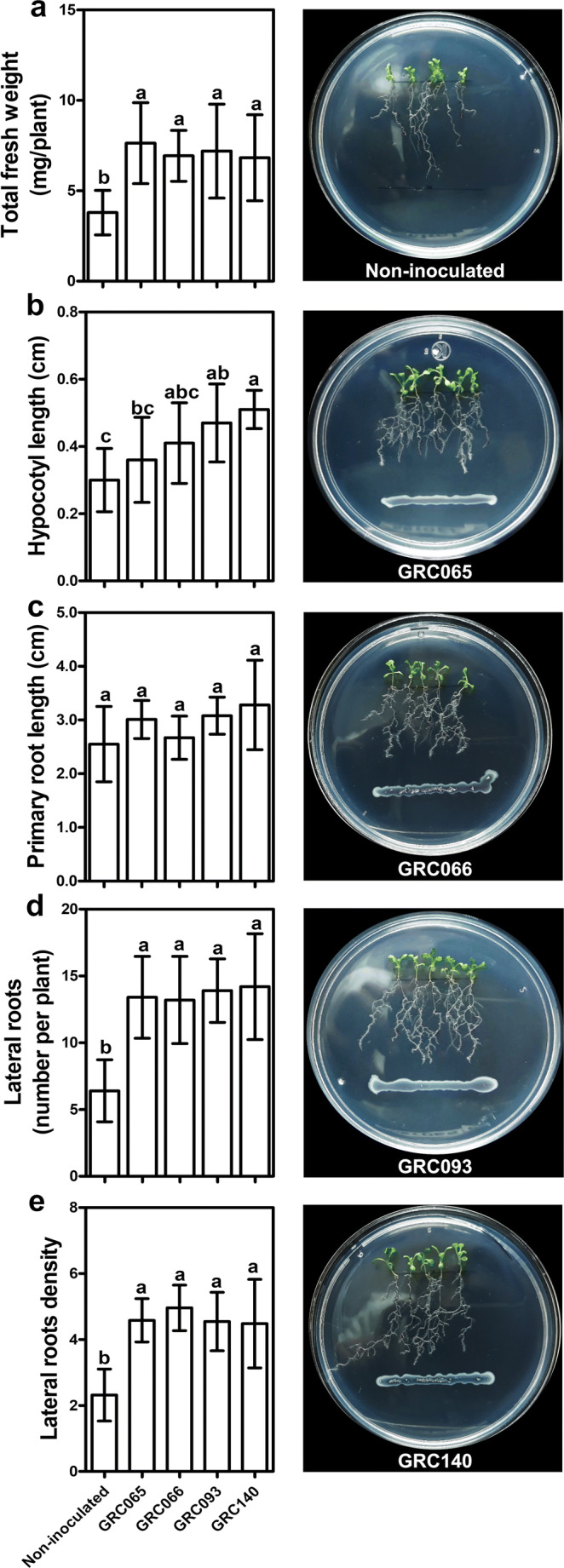

The determination of siderophores showed that the CAS solution turns color from blue to orange when mixed with cell-free supernatants of bacteria. These results indicated that the four P. rhodesiae strains secrete siderophores in a Fe-deficient minimal media (Fig. 4). Quantitative analysis showed that P. rhodesiae strains produce siderophores in a range from 0.60 ± 0.36 to 1.60 ± 0.55 units/ml. The order of siderophore production was GRC140 = GRC066 > GRC065 = GRC093 (Fig. 4), being P. rhodesiae GRC140 and GRC066 strains the best siderophore producers (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Siderophore production by P. rhodesiae strains using CAS assay. Bars represent the means ± SD (n = 6). Different letters represent means statistically different (p < 0.05)

Determination of bacterial auxins in the cell-free supernatants of LB broth with L-Trp showed that P. rhodesiae strains synthesized two auxins indole acetic acid (IAA) and phenylacetic acid (PAA). The IAA at concentrations range from 0.93 ± 0.03 to 1.31 ± 0.13 mg/l, while PAA 0.55 ± 0.06 and 0.81 ± 0.17 mg/l (Table 1). However, no statistical differences were observed between the amounts of auxins synthesized by P. rhodesiae strains. Moreover, CG-EIMS analysis identified intermediary compounds such as indole-3-ethanol (IE) and indole-3-lactic acid (ILA), which are involved in the synthesis of IAA (Fig. S3).

P. rhodesiae strains were inoculated in DF minimal media with 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) as the sole nitrogen source. Results showed that, except for GRC065, all P. rhodesiae strains were able to grow in the ACC culture medium (Table 1), indicating that they have ACC deaminase enzyme that contributes to the assimilation of ACC as N source. Besides, the acdS gene (750 bp) that encodes the ACC deaminase enzyme was amplified by PCR from the genome of four P. rhodesiae strains (Fig. S4). Results indicated that the acdS gene was not found only in the GRC065, while it was present in the other three strains, suggesting a correlation with results showed in biochemical tests.

P. rhodesiae strains promote the growth of A. thaliana seedlings

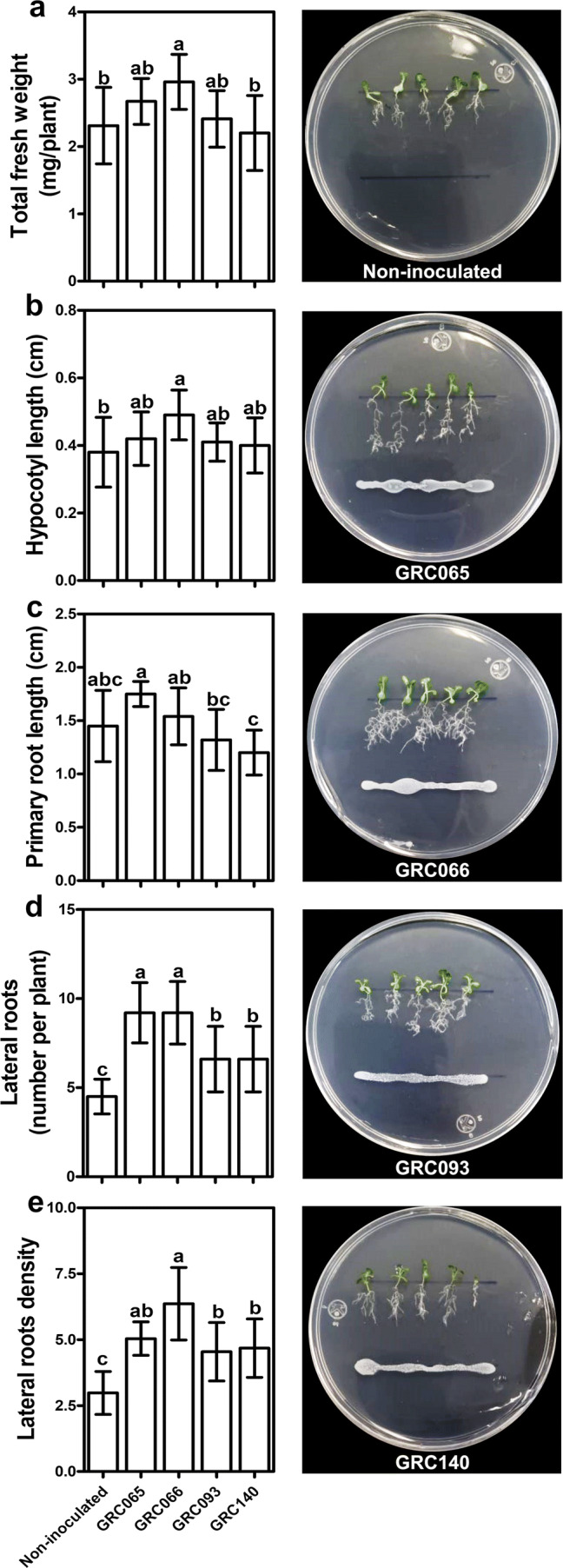

The effects of P. rhodesiae strains were evaluated on total fresh weight and hypocotyl length of A. thaliana seedlings. The four P. rhodesiae strains increased A. thaliana total fresh weight by about 80% with respect to non-inoculated seedlings (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5a). However, there were no differences in the average total fresh weight of plants inoculated with any of the bacterial strains. Moreover, the hypocotyl length was increased only by P. rhodesiae GRC093 and GRC140 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Effect of P. rhodesiae strains on A. thaliana seedlings. a Effect of bacterial isolates on total fresh weight, b hypocotyl length, c primary root length, d lateral roots number, and e lateral roots density. Bars represent the means ± SD (n = 10). Different letters represent means statistically different (p < 0.05)

Furthermore, we evaluated the effects of the four P. rhodesiae strains in the root architecture of A. thaliana seedlings. P. rhodesiae strains did not promote the growth of the primary root length (p > 0.05) (Fig. 5c); however, they increased twofold the number (p < 0.05) and density of lateral roots (p < 0.05) concerning non-inoculated plants (Fig. 5d, e). Despite this, bacterial strains caused similar effects on evaluated root parameters (p > 0.05).

Effect of P. rhodesiae strains in the growth of A. thaliana seedlings exposed to Cd

First, the Cd effects in A. thaliana seedlings were determined. The results showed that the presence of Cd in MS medium affected the general growth and primary root elongation of A. thaliana seedlings in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6). The presence of 2.5 and 5 mg/l of Cd in MS medium reduced by about 30% and 60%, the primary root length, concerning seedlings without Cd (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6a). Likewise, Cd concentrations from 7.5 to 10 mg/l inhibit the primary root development of A. thaliana seedlings (Fig. 6a). In comparison with control treatment, no statistical differences were observed in the length of the primary root and number and density of lateral roots of seedlings exposed to these Cd concentrations (Fig. 6a–c).

Fig. 6.

Effect of Cd on A. thaliana seedlings. a Effect of Cd on primary root length, b lateral roots number, and c lateral roots density. Bars represent the means ± SD (n = 5). Different letters represent means statistically different (p < 0.05)

On the other hand, the effects of P. rhodesiae strains in Cd tolerance were evaluated on A. thaliana seedlings exposed to 2.5 mg/l of Cd. It was observed that P. rhodesiae GRC066 increases the total fresh weight and length of the hypocotyl significantly in A. thaliana seedlings exposed to Cd (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7a, b). Despite that bacteria did not promote the growth of primary root length, they increased the number and density of lateral roots with concerning non-inoculated plants (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7d, e). These results indicated that P. rhodesiae strains modify the root system of A. thaliana seedlings exposed to Cd.

Fig. 7.

Effect of Pseudomonas rhodesiae strains on A. thaliana seedlings grown in the presence of 2.5 mg/l Cd. a Effect of bacterial isolates on total fresh weight, b hypocotyl length, c primary root length, d lateral roots number, and e lateral roots density. Bars represent the means ± SD (n = 10). Different letters represent means statistically different (p < 0.05)

Discussion

Previous studies with T. latifolia have described the physicochemical factors involved in the removal of Cd and other heavy metals [15, 32, 33]. However, bacteria associated with plant roots and their role in tolerance to heavy metals remain poorly understood.

T. latifolia roots used in this study absorbed Cd from the surrounding environment with a BCF of 0.32. This value is found between BCF ranges reported for T. latifolia and indicates that Cd accumulates in plant roots [29]. These roots are colonized by Cd-tolerant endophytic bacteria that can grow in culture media supplemented with 0.04 mM of CdCl2. According to MIC assays, the most Cd-tolerant bacteria were selected for characterization. The Blast analysis of the sequence of 16S rRNA, gyrA, and rpoD genes from four selected isolates showed high similarity with Pseudomonas rhodesiae (Table S3), which is closely related to P. fluorescens, a bacterium widely distributed in the rhizosphere of different plant species (Fig. 3) [34].

P. rhodesiae has been isolated from mineral water sources [35], environments contaminated with aromatic compounds [36], and from the roots of Vitis vinifera [37] and Cnidoscolus aconitifolius [38], and the endosphere of tomato leaves [39]. Also, P. rhodesiae has been identified, by culture-independent methods, as an endophyte in T. angustifolia roots that grow in artificial wetlands to treat domestic wastewater [40].

P. rhodesiae degrades nitro and chlorophenol derivatives [41] and polycyclic aromatic compounds, such as carbazoles, biphenyls, anthracene, naphthalene, and phenanthrene [36, 42, 43]. These skills indicate that it has a vast metabolic versatility. However, it is unknown its tolerance to Cd and its role inside the roots of T. latifolia exposed to Cd.

Regarding the MTC, our data indicated that P. rhodesiae GRC065 and GRC066 tolerate 7.12 mM of CdCl2, whereas GRC093 and GRC140 4.45 and 5.34 mM of CdCl2, respectively (Fig. 1). The four P. rhodesiae strains show higher tolerance to Cd than reported for P. fluorescens (0.505 mM) isolated from marine sediments of a Cd-contaminated bay [44]. The most Cd-tolerant P. rhodesiae strains GRC065 and GRC066 showed similar Cd tolerance (7.12 mM) to the reported P. putida CD2 (7.3 mM) isolated from wastewater from a steel manufacture industry [45]. Moreover, the four P. rhodesiae strains showed higher Cd tolerance than Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 (formerly Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34) (3.5 mM) and Cupriavidus metallidurans BS1 (2.5 mM) [30].

The presence of Cd-tolerant endophytic bacteria inside T. latifolia roots suggests that the plant selects bacterial communities that improve its growth in the Cd-contaminated site. High tolerance to metal ions is a fundamental characteristic of bacteria that inhabit contaminated environments since it allows them to survive and reproduce in these hostile conditions [46]. This characteristic is attributed to multiple mechanisms produced in response to metallic stress, including heavy metal efflux systems [47]. The czcCBA efflux system encodes an efflux pump involved in resistance to Cd, Zn, and Co in Gram-negative bacteria [46]. In the well-studied C. metallidurans CH34 (A. eutrophus CH34), the genes encoding czcCBA efflux system are found in plasmid pMOL30 [30, 48], whereas in P. putida CD2 and P. aeruginosa JP-11, they are distributed in the genome [49]. In this study, we identified the czcA gene that belongs to the czcCBA transcriptional unit in the genome of four P. rhodesiae strains, suggesting that CzcCBA multiproteic system is involved in tolerance to Cd in these strains. This mechanism could be responsible for P. rhodesiae strains adaptation to the roots of T. latifolia that grow at the Cd-contaminated site.

Previous studies have shown that endophytic bacteria from the plant roots decrease oxidative stress caused by heavy metals, improve phytoremediation, and contribute to plant growth [5, 50]. Therefore, the PGPR abilities of the P. rhodesiae strains were determined to understand their role inside the roots of T. latifolia growing at the Cd-contaminated site. The screening for PGPR biochemical properties indicated that the four P. rhodesiae strains exert similar levels of phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, IAA synthesis, and ACC deaminase activity, suggesting that they are PGPRs (Table 1). In plant-bacteria interaction assays, P. rhodesiae strains increased twofold the total fresh weight of A. thaliana seedlings (Fig. 5a). Our results agree with previous studies that showed the PGPR abilities of P. rhodesiae strain in vitro and in planta. P. rhodesiae BT2 strain isolated from the endosphere of tomato leaves has biochemical activities like a PGPRs and increases the fresh weight when it is inoculated in its host plant [39]. P. rhodesiae 50 isolated from the rhizosphere of C. aconitifolius exerts beneficial effect even in non-host plants. Bacterium increases twofold the primary root length of the non-host plant, Phaseolus vulgaris, whereas, in Bacopa monnieri, it increases fresh weight, the number of leaves and roots, and the length of roots and stems in inoculated plants [38]. In our study, the four P. rhodesiae strains isolated from T. latifolia increased twofold the number and density of lateral roots in the non-host plant, A. thaliana (Fig. 5d, e). These effects can be attributed to IAA that stimulates the formation of lateral and adventitious roots [51].

Furthermore, the GC-EIMS identified a second auxin produced by P. rhodesiae strains, the phenylacetic acid (PAA). PAA is also synthesized by the endophytic bacterium, Martelella endophytica YC6887, isolated from the root of the halophyte plant, Rosa rugosa. This bacterium promotes plant growth by increasing lateral roots number and fresh weight of A. thaliana seedlings [52]. On the other hand, it has found that PAA synthesized by Frankia sp. promotes lateral roots and pseudonodules development in Alnus glutinosa [53]. PAA synthesized by Pseudomonas spp., Streptomyces humidus strain S5-55, and Streptomyces malachitofuscus CTF9 has been demonstrated to exert antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi [54–56]. Thus, the effect of P. rhodesiae strains in the root system of A. thaliana seedlings could be attributed to IAA and PAA synthesized by them.

Concerning plants exposed to 2.5 mg/l of Cd, P. rhodesiae strains increased mainly the number and density of lateral roots (Fig. 7d, e). The results suggest that P. rhodesiae strains modify the root system of A. thaliana seedlings through IAA and PAA action to adapt their growth in Cd presence. However, other mechanisms could be involved to adapt to these conditions.

Heavy metals generate oxidative stress in plants, which increases ethylene levels, a phytohormone that exerts adverse effects on plant physiology, such as the premature fall of the leaves and the growth inhibition of the taproot [57]. To reduce ethylene levels, PGPRs hydrolyze 1-amino-cyclopropane (ACC), the precursor of ethylene biosynthesis in plants, by the action of the ACC deaminase enzyme that degrades ACC to ammonia and α-ketobutyrate, thus reducing ethylene level inside the plants [58]. Results indicated that P. rhodesiae GRC066, GRC093, and GRC140 strains possess ACC deaminase activity, which could be involved in the interaction of P. rhodesiae strains with A. thaliana seedlings.

Besides, it has been suggested that phosphate solubilization, by organic acids, and siderophore production are involved in tolerance to heavy metals due to they form complexes with them [59]. These mechanisms could be contributed to A. thaliana seedlings adaptation to Cd presence, in addition to the effects of IAA, PAA, and ACC deaminase. A similar Cd tolerance phenotype has been demonstrated in A. thaliana seedlings inoculated with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SAY09. This bacterium synthesizes IAA and volatile organic compounds, which activate auxin-mediated signaling pathways to increase Cd tolerance in A. thaliana seedlings [60].

This work demonstrated that P. rhodesiae strains promote A. thaliana seedlings growth in both the absence and presence of Cd. These results suggest that P. rhodesiae strains could exert similar effects inside the T. latifolia roots that grow at the Cd-contaminated site. P. rhodesiae strains decrease the Cd stress by ACC deaminase activity; the IAA and PAA improve root system adaptation to the soil, whereas phosphate solubilization and siderophores contribute to Cd complexes formation. These results are similar to the reported for Spartina densiflora [8, 9], and Sulla coronaria and their root-associated PGPRs that improve plant growth in heavy metal contaminated environments [10].

Finally, according to our knowledge, this is the first study aimed to isolate and characterize PGPRs from the T. latifolia roots that grow in a Cd-contaminated site. Currently, we work to understand the effect of P. rhodesiae in the tolerance and phytoextraction of Cd in A. thaliana and T. latifolia.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 1923 kb)

(XLSX 31 kb)

Author’s contributions

GARC (Ph. D. student) performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. JLAG, JRPA, and JVM participated in experimental design, contributed to bacterial characterization, and analyzed data. AHM conceived the study, analyzed data, and participated in the paper writing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work reported was funded by grants from CONACYT (Fondo Sectorial de Investigación para la Educación, CB2017-2018 A1-S-40454), Fondo de Apoyo a la Investigación (UASLP 2019 C19-FAI-05-40.40), and Fondos Concurrentes de la UASLP (FCR UASLP 210920280) to Alejandro Hernández-Morales. Gisela Adelina Rolón-Cárdenas (CVU 712240) thanks CONACYT-Mexico for the financial support given to carry out her Ph.D. studies.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Smith SG. Typha: its taxonomy and the ecological significance of hybrids. Archiv fü Hydrobiologie. 1987;27:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin B, Cannon A. Typha review. Logan: Utah State University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeke NN, Zvomuya F, Cicek N, Ross L, Badiou P. Biomass, nutrient, and trace element accumulation and partitioning in cattail (Typha latifolia L.) during wetland phytoremediation of municipal biosolids. J Environ Qual. 2015;44:1541–1549. doi: 10.2134/jeq2015.02.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bansal S, Lishawa SC, Newman S, Tangen BA, Wilcox D, Albert D, Anteau MJ, Chimney MJ, Cressey RL, DeKeyser E, Elgersma KJ, Finkelstein SA, Freeland J, Grosshans R, Klug PE, Larkin DJ, Lawrence BA, Linz G, Marburger J, Noe G, Otto C, Reo N, Richards J, Richardson C, Rodgers LR, Schrank AJ, Svedarsky D, Travis S, Tuchman N, Windham-Myers L. Typha (cattail) invasion in North American wetlands: biology, regional problems, impacts, ecosystem services, and management. Wetlands. 2019;39(4):645–684. doi: 10.1007/s13157-019-01174-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manoj SR, Karthik C, Kadirvelu K, Arulselvi PI, Shanmugasundaram T, Bruno B, Rajkumar M. Understanding the molecular mechanisms for the enhanced phytoremediation of heavy metals through plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: a review. J Environ Manag. 2020;254:109779. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santoyo G, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, del Carmen O-MM, Glick BR. Plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes. Microbiol Res. 2016;183:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong Z, Glick BR (2017) The role of plant growth-promoting bacteria in metal phytoremediation. In: Poole RK (ed) Adv Microb Physiol, vol 71. Academic Press, pp 97-132. doi:10.1016/bs.ampbs.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Paredes-Páliz KI, Caviedes MA, Doukkali B, Mateos-Naranjo E, Rodríguez-Llorente ID, Pajuelo E. Screening beneficial rhizobacteria from Spartina maritima for phytoremediation of metal polluted salt marshes: comparison of Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23(19):19825–19837. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paredes-Páliz KI, Mateos-Naranjo E, Doukkali B, Caviedes MA, Redondo-Gómez S, Rodríguez-Llorente ID, Pajuelo E. Modulation of Spartina densiflora plant growth and metal accumulation upon selective inoculation treatments: a comparison of Gram negative and Gram positive rhizobacteria. Mar Pollut Bull. 2017;125(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiboub M, Saadani O, Fatnassi IC, Abdelkrim S, Abid G, Jebara M, Jebara SH. Characterization of efficient plant-growth-promoting bacteria isolated from Sulla coronaria resistant to cadmium and to other heavy metals. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2016;339(9):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li YH, Liu QF, Liu Y, Zhu JN, Zhang Q. Endophytic bacterial diversity in roots of Typha angustifolia L. in the constructed Beijing Cuihu Wetland (China) Res Microbiol. 2011;162(2):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh UD, Saha C, Maiti M, Lahiri S, Ghosh S, Seal A, Mitra Ghosh M. Root associated iron oxidizing bacteria increase phosphate nutrition and influence root to shoot partitioning of iron in tolerant plant Typha angustifolia. Plant Soil. 2014;381(1):279–295. doi: 10.1007/s11104-014-2085-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saha C, Mukherjee G, Agarwal-Banka P, Seal A. A consortium of non-rhizobial endophytic microbes from Typha angustifolia functions as probiotic in rice and improves nitrogen metabolism. Plant Biol J. 2016;18(6):938–946. doi: 10.1111/plb.12485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diazbarriga F, Santos MA, Mejia JD, Batres L, Yanez L, Carrizales L, Vera E, Delrazo LM, Cebrian ME. Arsenic and cadmium exposure in children living near a smelter complex in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Environ Res. 1993;62(2):242–250. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1993.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carranza-Álvarez C, Alonso-Castro AJ, Alfaro-De La Torre MC, García-De La Cruz RF. Accumulation and distribution of heavy metals in Scirpus americanus and Typha latifolia from an artificial lagoon in San Luis Potosí, México. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2008;188(1–4):297–309. doi: 10.1007/s11270-007-9545-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheng X-F, Xia J-J. Improvement of rape (Brassica napus) plant growth and cadmium uptake by cadmium-resistant bacteria. Chemosphere. 2006;64:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ndeddy Aka RJ, Babalola OO. Identification and characterization of Cr-, Cd-, and Ni-tolerant bacteria isolated from mine tailings. Bioremediat J. 2017;21(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/10889868.2017.1282933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W-P, Kuo T-T. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of gram-negative bacterial genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21(9):2260–2260. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.9.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank JA, Reich CI, Sharma S, Weisbaum JS, Wilson BA, Olsen GJ. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(8):2461–2470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02272-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng X, Tang J, Liu X, Jiang P. Response of P. aeruginosa E1 gene expression to cadmium stress. Curr Microbiol. 2012;65(6):799–804. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shehata HR, Dumigan C, Watts S, Raizada MN. An endophytic microbe from an unusual volcanic swamp corn seeks and inhabits root hair cells to extract rock phosphate. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13479. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14080-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King J. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. Biochem J. 1932;26:292–297. doi: 10.1042/bj0260292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tank N, Rajendran N, Patel B, Saraf M. Evaluation and biochemical characterization of a distinctive pyoverdin from a Pseudomonas isolated from chickpea rhizosphere. Braz J Microbiol. 2012;43:639–648. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822012000200028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander DB, Zuberer DA. Use of chrome azurol S reagents to evaluate siderophore production by rhizosphere bacteria. Biol Fertil Soils. 1991;12:39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00369386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grunennvaldt RL, Degenhardt-Goldbach J, de Cássia TJ, Davila Dos Santos G, Aparecida Vicente V, Deschamps C. Bacillus megaterium: an endophytic bacteria from callus of Ilex paraguariensis with growth promotion activities. Biotecnología Vegetal. 2018;18(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dworkin M, Foster J. Experiments with some microorganisms which utilize ethane and hydrogen. J Bacteriol. 1958;75:592–601. doi: 10.1128/JB.75.5.592-603.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hontzeas N, Richardson AO, Belimov A, Safronova V, Abu-Omar MM, Glick BR. Evidence for horizontal transfer of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(11):7556–7558. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7556-7558.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remy E, Duque P. Assessing tolerance to heavy-metal stress in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. In: Duque P, editor. Environmental responses in plants: methods and protocols. New York: Springer New York; 2016. pp. 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonanno G, Cirelli GL. Comparative analysis of element concentrations and translocation in three wetland congener plants: Typha domingensis, Typha latifolia and Typha angustifolia. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2017;143:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazhar SH, Herzberg M, Ben Fekih I, Zhang C, Bello SK, Li YP, Su J, Xu J, Feng R, Zhou S, Rensing C. Comparative insights into the complete genome sequence of highly metal resistant Cupriavidus metallidurans strain BS1 isolated from a gold–copper mine. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:47. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chow LC. Solubility of calcium phosphates. In: Chow LC, Eanes ED, editors. Octacalcium phosphate. Basel: Karger; 2001. pp. 94–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alonso-Castro AJ, Carranza-Álvarez C, Alfaro-De la Torre MC, Chávez-Guerrero L, García-De la Cruz RF. Removal and accumulation of cadmium and lead by Typha latifolia exposed to single and mixed metal solutions. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2009;57(4):688–696. doi: 10.1007/s00244-009-9351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leura-Vicencio A, Alonso-Castro AJ, Carranza-Álvarez C, Loredo-Portales R, Alfaro-De La Torre MC, García-De La Cruz RF. Removal and accumulation of As, Cd and Cr by Typha latifolia. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2013;90(6):650–653. doi: 10.1007/s00128-013-0962-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kandasamy S, Loganathan K, Muthuraj R, Duraisamy S, Seetharaman S, Thiruvengadam R, Ponnusamy B, Ramasamy S. Understanding the molecular basis of plant growth promotional effect of Pseudomonas fluorescens on rice through protein profiling. Proteome Sci. 2009;7(1):47. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coroler L, Elomari M, Hoste B, Gillis M, Izard D, Leclerc H. Pseudomonas rhodesiae sp. nov., a new species isolated from natural mineral waters. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19(4):600–607. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(96)80032-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon B-J, Lee D-H, Kang Y-S, Oh D-C, Kim S-I, Oh K-H, Kahng H-Y. Evaluation of carbazole degradation by Pseudomonas rhodesiae strain KK1 isolated from soil contaminated with coal tar. J Basic Microbiol. 2002;42(6):434–443. doi: 10.1002/1521-4028(200212)42:6<434::Aid-jobm434>3.0.Co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolli E, Marasco R, Saderi S, Corretto E, Mapelli F, Cherif A, Borin S, Valenti L, Sorlini C, Daffonchio D. Root-associated bacteria promote grapevine growth: from the laboratory to the field. Plant Soil. 2017;410(1):369–382. doi: 10.1007/s11104-016-3019-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.John-Jimtha C, Radhakrishnan EK. Multipotent plant probiotic rhizobacteria from western ghats and its effect on quantitative enhancement of medicinal natural product biosynthesis. Proc Natl A Sci India B. 2016;88(2):755–768. doi: 10.1007/s40011-016-0810-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romero FM, Marina M, Pieckenstain FL. Novel components of leaf bacterial communities of field-grown tomato plants and their potential for plant growth promotion and biocontrol of tomato diseases. Res Microbiol. 2016;167(3):222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang R, Zhang Q, Huang X, Guo X. Endophytic bacterial diversity in roots of typha and the relationship of water quality factors in reclaimed water replenishment constructed wetland. China Environ Sci. 2016;36(3):875–886. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satchanska G, Topalova Y, Ivanov I, Golovinsky E. Xenobiotic biotransformation potential of Pseudomonas rhodesiae KCM-R5 and Bacillus subtilis KCM-RG5, tolerant to heavy metals and phenol derivatives. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2006;20(1):97–102. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2006.10817312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S-I, Kukor JJ, Oh K-H, Kahng H-Y. Evaluating the genetic diversity of dioxygenases for initial catabolism of aromatic hydrocarbons in Pseudomonas rhodesiae KK1. Enzym Microb Technol. 2006;40(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.10.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips LA, Germida JJ, Farrell RE, Greer CW. Hydrocarbon degradation potential and activity of endophytic bacteria associated with prairie plants. Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40(12):3054–3064. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poirier I, Jean N, Guary JC, Bertrand M. Responses of the marine bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens to an excess of heavy metals: physiological and biochemical aspects. Sci Total Environ. 2008;406(1–2):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu N, Zhao B. Key genes involved in heavy-metal resistance in Pseudomonas putida CD2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;267:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maynaud G, Brunel B, Mornico D, Durot M, Severac D, Dubois E, Navarro E, Cleyet-Marel J-C, Le Quéré A. Genome-wide transcriptional responses of two metal-tolerant symbiotic Mesorhizobium isolates to zinc and cadmium exposure. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y, Chao Y, Li Y, Lin Q, Bai J, Tang L, Wang S, Ying R, Qiu R. Survival strategies of the plant-associated bacterium Enterobacter sp. strain EG16 under cadmium stress. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(6):1734–1744. doi: 10.1128/aem.03689-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mergeay M, Nies D, Schlegel HG, Gerits J, Charles P, Van Gijsegem F. Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 is a facultative chemolithotroph with plasmid-bound resistance to heavy metals. J Bacteriol. 1985;162(1):328–334. doi: 10.1128/JB.162.1.328-334.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chellaiah ER. Cadmium (heavy metals) bioremediation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a minireview. Appl Water Sci. 2018;8(6):154. doi: 10.1007/s13201-018-0796-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ullah A, Heng S, Munis MFH, Fahad S, Yang X. Phytoremediation of heavy metals assisted by plant growth promoting (PGP) bacteria: a review. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;117:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baca BE, Elmerich C. Microbial production of plant hormones. In: Elmerich C, Newton WE, editors. Associative and endophytic nitrogen-fixing bacteria and cyanobacterial associations. Netherlands: Springer; 2007. pp. 113–143. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan A, Hossain MT, Park HC, Yun D-J, Shim SH, Chung YR. Development of root system architecture of Arabidopsis thaliana in response to colonization by Martelella endophytica YC6887 depends on auxin signaling. Plant Soil. 2016;405(1):81–96. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2775-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammad Y, Nalin R, Marechal J, Fiasson K, Pepin R, Berry AM, Normand P, Domenach A-M. A possible role for phenyl acetic acid (PAA) on Alnus glutinosa nodulation by Frankia. Plant Soil. 2003;254(193):193–205. doi: 10.1023/A:1024971417777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang JG, Kim ST, Kang KY. Production of the antifungal compound phenylacetic acid by antagonistic bacterium Pseudomonas sp. J Appl Biol Chem. 1999;42(2):197–201. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang BK, Lim SW, Kim BS, Lee JY, Moon SS. Isolation and in vivo and in vitro antifungal activity of phenylacetic acid and sodium phenylacetate from Streptomyces humidus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(8):3739–3745. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3739-3745.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sajid I, Shaaban KA, Hasnain S. Identification, isolation and optimization of antifungal metabolites from the Streptomyces malachitofuscus ctf9. Braz J Microbiol. 2011;42(2):592–604. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220110002000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnston-Monje D, Raizada MN. Plant and endophyte relationships: nutrient management. In: Moo-Young M, editor. Comprehensive biotechnology. 2. Oxford: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 713–727. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glick BR. Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol Res. 2014;169(1):30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osmolovskaya N, Dung VV, Kuchaeva L. The role of organic acids in heavy metal tolerance in plants. Bio Comm. 2018;63(1):9–16. doi: 10.21638/spbu03.2018.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou C, Zhu L, Ma Z, Wang J. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SAY09 increases cadmium resistance in plants by activation of auxin-mediated signaling pathways. Genes. 2017;8(7):173. doi: 10.3390/genes8070173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 1923 kb)

(XLSX 31 kb)