Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Physical activity (PA) has the potential to attenuate cardiovascular disease risk in midlife women through multiple pathways, including improving lipid profiles. Longitudinal patterns of PA and blood lipid levels have not been studied in midlife women. Our study identified trajectories of PA and blood lipids across midlife and characterized the associations between these trajectories.

METHODS:

We evaluated 2,789 participants from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a longitudinal cohort study with follow-up over the menopause transition. Women reported PA using the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey at seven study visits across 17 years of follow-up. Serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured at eight study visits across the same 17-year follow-up period. We used group-based trajectory models to characterize trajectories of PA and blood lipids over midlife and dual trajectory models to determine the association between PA and blood lipid trajectories adjusted for race/ethnicity, body mass index category, smoking, and lipid-lowering medication use.

RESULTS:

Women were 46 years old, on average, at study entry. Forty-nine percent were non-Hispanic white; 32% were Black; 10% were Japanese; and 9% were Chinese. We identified four PA trajectories, three HDL cholesterol trajectories, four LDL cholesterol trajectories, and two triglyceride trajectories. The most frequently occurring trajectories were the consistently low PA trajectory (69% of women), the low HDL cholesterol trajectory (43% of women), the consistently moderate LDL cholesterol trajectory (45% of women), and the consistently low triglycerides trajectory (90% of women). In dual trajectory analyses, no clear associations were observed between PA trajectories and HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, or triglycerides trajectories.

CONCLUSIONS:

The most frequently observed trajectories across midlife were characterized by low physical activity, low HDL cholesterol, moderate LDL cholesterol, and low triglycerides. Despite the absence of an association between long-term trajectories of PA and blood lipids in this study, a large body of evidence has established the importance of clinical and public health messaging and interventions targeted at midlife women to promote regular and sustained PA during midlife to achieve other cardiovascular and metabolic benefits.

Keywords: Physical activity, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, trajectory, midlife

Introduction

Midlife women experience increases in low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglyceride levels [1, 2], creating a lipid profile associated with high cardiovascular disease risk [3, 4]. Additionally, the quality of HDL molecules in midlife women seems to be compromised, further raising their risk for cardiovascular disease [1, 5, 6].

Physical activity improves cardiovascular and metabolic health across the lifecourse, reducing the risk of obesity [7], type 2 diabetes [8, 9], high blood pressure [10], and cardiovascular disease [9], including coronary heart disease [11, 12] and stroke [13, 14]. In women, physical activity has the potential to attenuate the detrimental changes in cardiovascular disease risk, including changes in blood lipid levels [15–18], that occur during the midlife period [19, 20].

Long-term trajectories of physical activity and blood lipids in midlife women and the impact of physical activity on blood lipid levels measured longitudinally across midlife are still unclear and understudied in population-based samples. Few studies have longitudinal data in midlife women to explore these patterns and associations. Previous prospective studies and randomized controlled trials have explored these associations in younger and older women [17, 18], supporting beneficial associations of physical activity and blood lipid levels, particularly HDL and triglycerides, in these populations. Because changes in blood lipid levels occur across midlife in women, it is important to consider changes in physical activity and blood lipid levels jointly across this stage of life. The objectives of this study were to identify patterns of physical activity, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides across midlife and to characterize associations between identified patterns of physical activity and patterns of blood lipids.

Methods

Study setting and study population

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) is a longitudinal cohort study of a racially and ethnically diverse cohort of women transitioning from midlife to late adulthood. A total of 3302 pre- and early peri-menopausal women who were 42-52 years old in 1996-97 were recruited from seven geographic sites across the United States: Boston MA, Chicago IL, Detroit area MI, Los Angeles CA, Newark NJ, Oakland CA, and Pittsburgh PA. Women were eligible if they had an intact uterus and at least one ovary, reported a menstrual period and no exogenous hormone use in the three months prior to recruitment, were not currently pregnant or lactating, and identified their primary race/ethnicity as Black (at the Boston, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh sites), Japanese (at the Los Angeles site), Hispanic (at the Newark site), Chinese (at the Oakland site), or white (at all sites). The sampling and recruitment strategies have been previously described in greater detail [21].

Women completed near-annual follow-up study visits through 2011 (follow-up visit 13). Data collection was halted mid-study and later resumed at the Newark site (N=432), the only site to recruit Hispanic participants, leading to a lack of necessary longitudinal data for this analysis and exclusion of women from the Newark site. Women with unknown menopause status at the baseline study visit (n=30), no physical activity data at any visit (n=8), no lipid data at any visit (n=2), and missing baseline covariates included in trajectory models (body mass index [BMI] or smoking status, n=41) were also excluded. The final analytic sample thus included 2789 women. Exclusion of participants from the Newark site excluded all Hispanic women and a portion of non-Hispanic white women from our analyses. Excluded women on average also had a lower baseline physical activity score and were more likely to have at most a high school education and overweight or obesity at the baseline study visit (Supplemental Table 1).

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating institutions. All participants provided written informed consent at each study visit.

Data collection

Physical activity

Physical activity data were collected using the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey, a self-administered questionnaire [22, 23], The sports and exercise index within the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey was used to estimate moderate and vigorous intensity leisure time physical activity exposure. At baseline (1996-97) and follow up study visit 3 (1999-2000), visit 5 (2001-02), visit 6 (2002-03), visit 9 (2005-06), visit 12 (2010-11), and visit 13 (2011-13), participants were asked to report up to two sports and exercise activities of at least moderate intensity (≥3 METs) that they engaged in most frequently over the previous 12 months. For each activity, participants also reported frequency (number of months per year) and duration (number of hours per week) of engaging in the activity. Reported sports and exercise activities were coded by intensity and multiplied by the reported frequency and duration. The resulting score was mapped to a scale, ranging from 1 to 5 [23], We dichotomized the physical activity score at the 75th percentile of its distribution (≥3.75) to establish categories of low vs high activity.

Blood lipids

Fasting plasma blood samples (minimum 10-hour fast) were collected, separated, frozen at −80°C, and sent on dry ice to the Medical Research Laboratory in Lexington KY (baseline through visit 7) and the University of Michigan Pathology Lab in Ann Arbor MI (visit 8 through visit 13). Both laboratories are CLIA-certified and accredited by the College of American Pathologists. Lipid fractions were determined from EDTA-treated plasma [24, 25], Measurements were performed on a Hitachi 747-200 analyzer (Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Indianapolis IN) at the Medical Research Laboratory and on an ADVIA 2400 automated chemistry analyzer (Siemens, Washington DC) at the University of Michigan Pathology Lab. At the Medical Research Laboratory, HDL cholesterol was isolated with heparin and manganese chloride. At the University of Michigan Pathology Lab, HDL cholesterol was isolated based on the method of Izawa et al [26]. LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald equation [27]. Triglycerides were determined by coupled enzymatic methods. Lipid assays were run only at baseline and follow up study visit 1, visit 3, visit 4, visit 5, visit 6, visit 7, visit 12, and visit 13 due to fiscal limitations. A cross-calibration study was conducted to ensure comparability in measures across the two laboratories.

Covariates

Standardized questionnaires were used to collect information on participants’ age, race/ethnicity [28], sociodemographic characteristics (educational attainment [28]), health behaviors (smoking status [29], alcohol consumption [30]), and medical characteristics (menopause status [31], hormone use [28, 32, 33], and lipid-lowering medication use [28, 32, 33]) at each study visit. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated using height, measured by stadiometer, and weight, measured using a calibrated balance beam scale. BMI was categorized using standard adult BMI outpoints for Black and white women [34]: underweight: <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: 18.5-24.9 kg/m2; overweight 25-29.9 kg/m2; obese: ≥30 kg/m2, and using Asian-specific BMI cutpoints for Chinese and Japanese women [35]: underweight: <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: 18.5-22.9 kg/m2; overweight 23-27.4 kg/m2; obese: ≥27.5 kg/m2.

Statistical analyses

Sociodemographic and medical characteristics at baseline were summarized for all women. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe continuous variables. Frequency and percentage were used to describe categorical variables.

Group-based trajectory analysis [36–38] was used to identify individual trajectories of the probability of having a physical activity score ≥3.75 and each lipid outcome: HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides over the SWAN follow up period though visit 13. Group-based trajectory analysis is a data-driven approach that assumes the population is composed of a mixture of distinct groups defined by their trajectories. The number of distinct trajectories and form (shape) of these trajectories were identified through a series of steps guided by comparison of Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) for different models and plausibility and interpretability of trajectories. Covariates were not included in models for identification of trajectories. A model (logit for physical activity score ≥3.75, censored normal for each lipid outcome) with chronological age as the time scale was used to calculate sets of probability distributions for trajectory groups using maximum likelihood. Log Bayes factor (2ΔBIC) >10 was considered strong evidence for a better model [36].

First, to determine the optimal number of trajectory groups, models with different numbers of trajectory groups with all groups of a quadratic form were compared. Next, to determine the form of the identified trajectories, the form of all identified trajectory groups was varied (linear, quadratic, cubic) to find the best form for each trajectory group. We identified four physical activity trajectories (all quadratic form), three HDL cholesterol trajectories (all quadratic form), four LDL cholesterol trajectories (all cubic form), and two triglyceride trajectories (all cubic form). All final trajectories had mean posterior membership probability >0.70 and odds of correct classification ≥5, indicating good model fit for all trajectory models [39] (Supplemental Table 2).

To assess unadjusted associations between identified physical activity trajectories and trajectories for each lipid outcome, Chi-square tests were used. To assess adjusted associations, the determined number and form of trajectory groups for each variable was used in a dual trajectory analysis of physical activity and each lipid outcome to calculate the probability of membership in each lipid outcome trajectory conditional on membership in each physical activity trajectory. Dual trajectory models were adjusted for a priori-selected time-stable covariates [race/ethnicity (white, Black, Japanese, Chinese), BMI category at baseline (underweight/normal weight, overweight, obese), smoking status at baseline (current, former, never)] and time-varying covariates (lipid-lowering medication use at each study visit). Adjusted conditional probabilities were calculated, with percentile-based 95% confidence intervals for adjusted conditional probabilities bootstrapped with 1000 replications. A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was used for statistical significance in all analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and Stata 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station TX).

Results

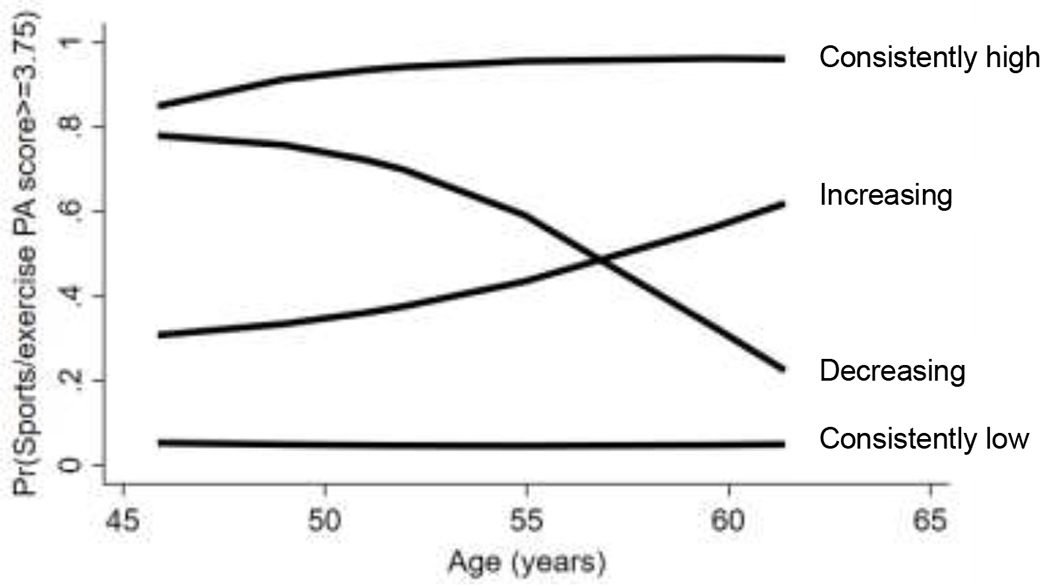

SWAN participants were, on average, 46 years old (SD=2.7 years) at baseline (Table 1). Forty-nine percent of participants were white, 32% were Black, 10% were Japanese, and 9% were Chinese. All participants were in pre-menopause or early perimenopause at baseline, and most had overweight or obesity (62%). Across the 17-year follow up period, 69% of women had a consistently low probability of having physical activity in the highest quartile of the distribution of the physical activity score (consistently low physical activity trajectory); 16% had an increasing probability of having physical activity in the highest quartile of the distribution of the physical activity score (increasing physical activity trajectory); 4% had a decreasing probability of having physical activity in the highest quartile of the distribution of the physical activity score (decreasing physical activity trajectory); and 12% had a consistently high probability of having physical activity in the highest quartile of the distribution of the physical activity score (consistently high physical activity trajectory) (Figure 1). Women in the consistently high physical activity trajectory were more likely to be non-Hispanic white, have a post-graduate education, have a normal weight BMI, have more alcohol use, and have higher HDL cholesterol and lower LDL cholesterol and triglycerides at baseline, on average, than women in the other physical activity trajectory groups.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and medical characteristics of SWAN participants at baseline by physical activity (PA) trajectory

| Overall (n=2789) |

Consistently low PA (n=1911) |

Increasing PA (n=440) |

Decreasing PA (n=108) |

Consistently high PA (n=330) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 45.9 (2.7) | 45.8 (2.7) | 45.9 (2.7) | 46.1 (2.7) | 45.9 (2.8) |

| Sports/exercise physical activity index score, mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.6) |

| Sports/exercise physical activity index score, median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.8) | 2.3 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.3) | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| Missing, n | 69 | 53 | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 57 (15) | 55 (15) | 58 (14) | 59 (15) | 61 (14) |

| Missing, n | 19 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 3 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 116 (31) | 117 (32) | 115 (30) | 113 (31) | 109 (29) |

| Missing, n | 154 | 110 | 26 | 4 | 14 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 110 (78) | 115 (83) | 103 (56) | 99 (61) | 94 (75) |

| Missing, n | 130 | 90 | 25 | 3 | 12 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1375 (49) | 835 (44) | 241 (55) | 67 (62) | 232 (70) |

| Black | 894 (32) | 724 (38) | 106 (24) | 21 (19) | 43 (13) |

| Japanese | 274 (10) | 171 (9) | 54 (12) | 12 (11) | 37 (11) |

| Chinese | 246 (9) | 181 (9) | 39 (9) | 8 (7) | 18 (5) |

| Education, n (%) | |||||

| Less than high school | 100 (4) | 86 (5) | 9 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) |

| High school graduate | 469 (17) | 377 (20) | 55 (13) | 10 (9) | 27 (8) |

| Some college/technical school | 922 (33) | 667 (35) | 141 (32) | 36 (33) | 78 (24) |

| College graduate | 597 (22) | 380 (20) | 106 (24) | 30 (28) | 81 (25) |

| Post graduate education | 685 (25) | 389 (20) | 127 (29) | 32 (30) | 137 (42) |

| Missing | 16 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| BMI category, n (%) | |||||

| Underweight | 47 (2) | 34 (2) | 5 (1) | 1 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Normal weight | 1021 (37) | 578 (30) | 190 (43) | 56 (52) | 197(60) |

| Overweight | 777 (28) | 517 (27) | 138 (31) | 30 (28) | 92 (28) |

| Obese | 944 (34) | 782 (41) | 107 (24) | 21 (19) | 34 (10) |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |||||

| Pre-menopause | 1505 (54) | 1005 (53) | 253 (58) | 51 (47) | 196 (59) |

| Early perimenopause | 1284 (46) | 906 (47) | 187 (43) | 57 (53) | 134 (41) |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | |||||

| None | 1323 (50) | 992 (55) | 183 (44) | 37 (35) | 111 (35) |

| <1/week | 263 (10) | 177 (10) | 40 (10) | 16 (15) | 30 (9) |

| 1-7/week | 656 (25) | 419 (23) | 109 (26) | 34 (32) | 94 (29) |

| >7/week | 405 (15) | 218 (12) | 85 (20) | 18 (17) | 84 (26) |

| Missing | 142 | 105 | 23 | 3 | 11 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| Never | 1586 (57) | 1076 (56) | 268 (61) | 59 (55) | 183 (55) |

| Former | 722 (26) | 445 (23) | 121 (28) | 38 (35) | 118 (36) |

| Current | 481 (17) | 390 (20) | 51 (12) | 11 (10) | 29 (9) |

Using Asian-specific BMI cutoffs for Chinese and Japanese women

Figure 1. Physical activity trajectories.

Identified physical activity trajectories across midlife: consistently low (69% of women in our cohort), decreasing (4%), increasing (16%), consistently high (12%)

Percentages do not total to 100% due to rounding.

HDL cholesterol

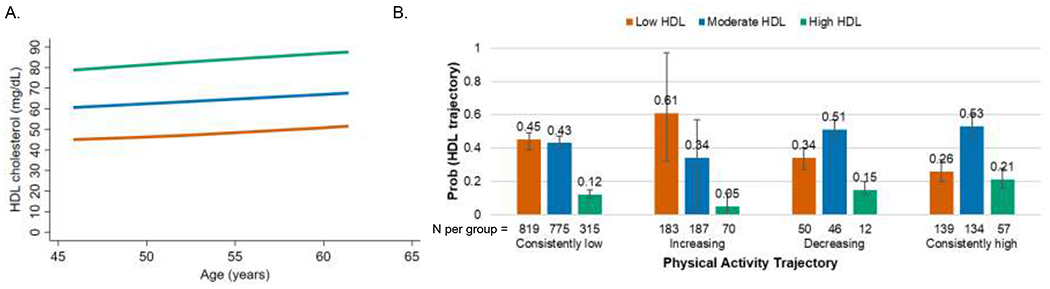

The three identified HDL cholesterol trajectories were characterized by differences in level of HDL cholesterol, and all had similarly increasing HDL cholesterol with increasing age (Figure 2A). Across the follow up period, 43% of women were in the low HDL cholesterol trajectory; 41% were in the moderate HDL cholesterol trajectory; and 16% were in the high HDL cholesterol trajectory. In unadjusted analyses, no associations were observed between physical activity and HDL cholesterol trajectories (P=0.81). In adjusted dual trajectory analyses (Figure 2B), women in the consistently low and increasing physical activity trajectories had higher conditional probability of being in the low HDL cholesterol trajectory than in the high HDL cholesterol trajectory. Women in the decreasing and consistently high physical activity trajectories had higher conditional probability of being in the moderate HDL cholesterol trajectory than in the low or high HDL cholesterol trajectories.

Figure 2. HDL cholesterol trajectories and adjusted conditional probabilities of HDL cholesterol trajectory by physical activity trajectories.

A. Identified HDL cholesterol trajectories: orange= low (43% of women in our cohort), blue= moderate (41%), green= high (16%).

B. Conditional probabilities of HDL cholesterol trajectory by physical activity trajectory adjusted for race/ethnicity, baseline body mass index category, baseline smoking, and time-varying lipid-lowering medication use

LDL cholesterol

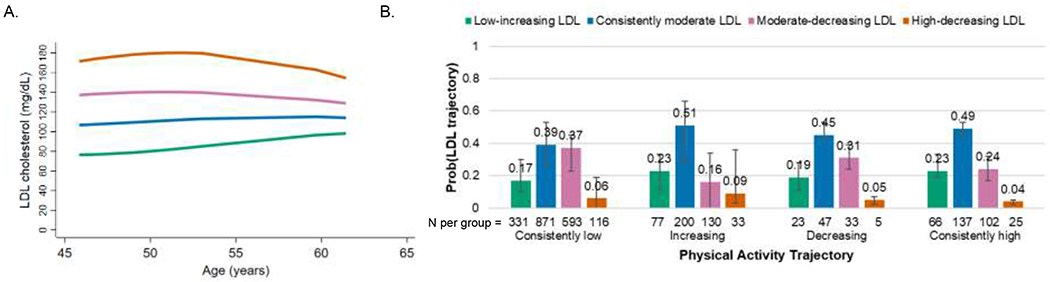

The four identified LDL cholesterol trajectories were characterized by differences in level of LDL cholesterol and differences in change in LDL cholesterol with increasing age (Figure 3A). Across the follow up period, 18% of women were in the low-increasing LDL cholesterol trajectory; 45% were in the consistently moderate LDL cholesterol trajectory; 31% were in the moderate-decreasing LDL cholesterol trajectory; and 6% were in the high-decreasing LDL cholesterol trajectory. In unadjusted analyses, no associations were observed between physical activity and LDL cholesterol trajectories (P=0.77). In adjusted dual trajectory analyses (Figure 3B), women in all physical activity trajectories had a higher conditional probability of being in the consistently moderate LDL trajectory than in the low-increasing or high-decreasing LDL cholesterol trajectories. Women in the consistently low physical activity trajectory also had a higher conditional probability of being in the moderate-decreasing LDL cholesterol trajectory than in the low-increasing or high-decreasing LDL cholesterol trajectory.

Figure 3. LDL cholesterol trajectories and adjusted conditional probabilities of LDL cholesterol trajectory by physical activity trajectories.

A. Identified LDL cholesterol trajectories: green=low-increasing (18% of women in our cohort), blue=consistently moderate (45%), pink=moderate-decreasing (31%), orange=high-decreasing (6%).

B. Conditional probabilities of LDL cholesterol trajectory by physical activity trajectory adjusted for race/ethnicity, baseline body mass index category, baseline smoking, and time-varying lipid-lowering medication use

Triglycerides

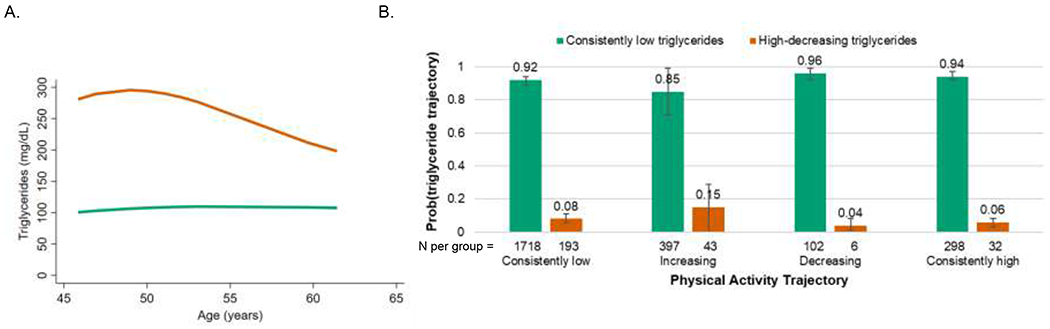

Across the follow up period, 90% of women were in the consistently low triglycerides trajectory, and 10% were in the high-decreasing triglycerides trajectory (Figure 4A). In unadjusted analyses, no associations were observed between physical activity and triglycerides trajectories (P=0.50). In adjusted dual trajectory analyses (Figure 4B), women in all physical activity trajectories had a higher conditional probability of being in the consistently low triglycerides trajectory compared to the high-decreasing triglycerides trajectory.

Figure 4. Triglycerides trajectories and adjusted conditional probabilities of triglycerides trajectory by physical activity trajectories.

A. Identified triglycerides trajectories: green=consistently low (90% of women in our cohort), orange=high-decreasing (10%).

B. Conditional probabilities of triglycerides trajectory by physical activity trajectory adjusted for race/ethnicity, baseline body mass index category, baseline smoking, and time-varying lipid-lowering medication use

Discussion

In the SWAN cohort of midlife women, the most frequently occurring trajectories across midlife were characterized by low physical activity, low or moderate HDL cholesterol, moderate LDL cholesterol, and low triglycerides across 17 years of follow-up that spanned the menopause transition. We did not observe clear associations between physical activity trajectories and HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, or triglycerides trajectories across follow up.

Interestingly, we observed HDL cholesterol trajectories that were slightly increasing with age, with 57% of women in the moderate or high HDL trajectories, despite most women having consistently low physical activity. This is consistent with a previously reported 0.4 mg/dL increase in HDL cholesterol per year in a subset of the SWAN cohort over nine years of follow up[40] and increasing HDL cholesterol levels across midlife in the Dutch LifeLines Cohort [41] and UK Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development [42]. A growing body of literature has suggested that higher levels of HDL cholesterol are associated with greater cardiovascular disease risk in women traversing menopause [5, 6, 40, 43, 44], in contrast to associations of lower HDL cholesterol levels with greater cardiovascular disease risk in younger women [45]. This may be explained by changes in the quality of HDL over the menopause transition that could not be captured by the static measure of the cholesterol components of HDL particles used in this study [5]. It is critical to assess changes in other metrics of HDL, which may be better indicators of cardiovascular disease risk in midlife women, such as HDL-cholesterol efflux capacity and HDL subclasses [5], during midlife in future studies.

We also observed that most women in our study had levels of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides that are considered clinically low or not risk-enhancing across the study period [46], with 63% of women with low-increasing or consistently moderate LDL cholesterol levels and 90% of women with consistently low triglyceride levels. Despite most women having consistently low physical activity in our cohort, women had other healthy habits that suggest healthy lifestyles: over half (57%) of women were never smokers, and half (50%) reported no alcohol use, which may have contributed to the clinically low and not-risk enhancing LDL cholesterol and triglycerides trajectories observed in our study. Previous analyses of the SWAN cohort with 9-11 years of follow up have observed increasing mean LDL cholesterol until 12 months after the final menstrual period and increasing triglyceride levels with increasing age [1, 2]; however these previous analyses were limited by the shorter follow up time, which failed to capture an additional inflection point observed with longer follow up in our current study, particularly for LDL cholesterol. A recent study using data from the UK Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development observed trajectories of decreasing LDL cholesterol levels and triglyceride levels across midlife [42], Our results for triglycerides are consistent with a previous report from the Women’s Health Study in which 67% of midlife women had low fasting triglyceride levels (≤147 mg/dL) [47], Previous research suggests that functionality of blood lipids, in addition to concentration, may play a role in the development of cardiovascular disease. LDL particle size and oxidized LDL may be better indicators of cardiovascular disease risk in midlife and postmenopausal women than LDL cholesterol concentration [48, 49].

We would expect that women in the consistently high physical activity trajectory would have the most favorable lipid profiles compared to those in the other physical activity trajectory groups. In analyses of physical activity and HDL cholesterol, our results showed that women with consistently high physical activity were more likely to have moderate HDL than low or high HDL; however, women with decreasing physical activity also had the same beneficial association, which was not consistent with our expected association of consistently high physical activity with the high HDL cholesterol profile. Women in all physical activity trajectories had similar probabilities of being in each identified LDL cholesterol and triglycerides trajectory, which was also not consistent with our expected association between consistently high physical activity and low-risk lipid profiles.

Few studies have examined associations between long-term physical activity and blood lipid levels. In the Healthy Women Study, greater level of physical activity over 17 years spanning the menopause transition was associated with a small decrease in triglyceride levels (3 mg/dL decrease per 100 kilocalories of energy expended in physical activity), but not with changes in HDL or LDL cholesterol levels, in within-person analyses [50]. Another study conducted in a population of Norwegian adults (20-49 years old) reported associations of sustained high physical activity over seven years with 3 mg/dL higher HDL and 13 mg/dL lower triglycerides [18]. Associations were strongest among the oldest study participants. Measures of physical activity in these previous studies include additional domains beyond leisure time physical activity, such as transportation, which may explain differences in results compared to those of our study. Previous studies have not examined long-term patterns of physical activity and blood lipids in midlife women across the menopause transition, as we did in our study. Our use of group-based trajectory analysis to categorize women by pattern of blood lipids may have limited our ability to detect the small changes in HDL cholesterol and triglycerides associated with greater physical activity previously observed in other studies.

Other studies have assessed the impact of increasing physical activity on blood lipid levels through interventions in midlife women across shorter periods of time, with generally beneficial associations, though associations with individual blood lipids have been inconsistent. In premenopausal midlife women with dyslipidemia, a 12-week water-based aerobic training intervention increased HDL cholesterol levels and reduced LDL cholesterol levels but did not change triglyceride levels [51]. In postmenopausal women with dyslipidemia, water-based aerobic and resistance training interventions increased HDL cholesterol levels and decreased LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels [52]. In healthy perimenopausal women, a 12-week walking intervention reduced triglyceride levels but did not change HDL or LDL cholesterol levels [53]. Additionally, in a cross-sectional observational study of premenopausal women in the Healthy Women Study, Owens et al reported associations of moderate physical activity level with higher HDL cholesterol levels and high physical activity level with lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol [54]. The results of these previous studies suggest beneficial short-term associations between higher levels of physical activity, which can be achieved through physical activity interventions, and blood lipids, but lack long term follow up to determine if these beneficial associations are sustained. We did not observe associations between physical activity and blood lipids over a longer time period in our observational cohort study.

The strengths of our study include repeated measurement of physical activity and blood lipid levels over 17 years of follow up in a large, diverse cohort of midlife women followed over the menopause transition and use of a data-driven approach to characterize patterns of physical activity and blood lipid levels across midlife. However, a few limitations should also be considered in the context of the findings. First, physical activity was self-reported, which may have introduced measurement error in physical activity; however, the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey is a validated measure of physical activity in this population [23]. Second, we were unable to include participants from the Newark, NJ SWAN study site due to limitations with availability of longitudinal data, which excluded all Hispanic women and a portion of non-Hispanic white women from our analyses. Third, we only identified two triglyceride trajectories, with 90% of women in one category, which limited our ability to assess associations of physical activity patterns with triglyceride patterns. Fourth, while we adjusted for BMI and smoking in our analysis, we did not adjust for dietary intake or alcohol consumption (additional behaviors that are often associated with physical activity and may affect lipid levels) due to issues with model convergence when including additional covariates in trajectory models. Finally, we did not include additional domains of physical activity beyond leisure time because information on intensity for these domains was not available.

In conclusion, consistently low physical activity was frequently observed in the midlife women in our cohort, but we did not observe a clear pattern for associations between long-term trajectories of physical activity and blood lipid profiles across midlife. Although we did not observe associations between physical activity and blood lipid trajectories, increasing physical activity in midlife women should be encouraged using clinical and public health messaging and interventions because of its beneficial associations with blood lipids in the short term as well as other cardiovascular and metabolic benefits [8–14].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Trajectories of physical activity and lipids were identified in midlife women.

Consistently low physical activity was most prevalent.

Consistently low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides were most prevalent.

Consistently moderate low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was most prevalent.

No associations were observed between physical activity and lipid trajectories.

Acknowledgements

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor — Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 — present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994-2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA — Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 — present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 — 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL — Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 — present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 — 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser — Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles — Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY — Carol Derby, PI 2011 — present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010 — 2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 — 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry — New Jersey Medical School, Newark — Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 — 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA — Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD — Chhanda Dutta 2016-present; Winifred Rossi 2012—2016; Sherry Sherman 1994 — 2012; Marcia Ory 1994 — 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD — Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor — Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA — Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012 - present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 – 2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 – 2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair

Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Funding

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061; U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH. This publication was supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131. SEB was funded in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant T32DK11668401) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant K99HD100585) at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating institutions. All participants provided written informed consent at each study visit.

Provenance and peer review

This article was not commissioned and was externally peer reviewed.

Research data (data sharing and collaboration)

SWAN provides access to public use datasets that include data from SWAN screening, the baseline visit and follow-up visits (https://agingresearchbiobank.nia.nih.gov/). To preserve participant confidentiality, some, but not all, of the data used for this manuscript are contained in the public use datasets. A link to the public use datasets is also located on the SWAN web site: http://www.swanstudy.org/swan-research/data-access/. Investigators who require assistance accessing the public use dataset may contact the SWAN Coordinating Center at the following email address: swanaccess@edc.pitt.edu.

Contributor Information

Sylvia E Badon, Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, Oakland CA.

Kelley Pettee Gabriel, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, Birmingham, AL.

Carrie Karvonen-Gutierrez, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor MI.

Barbara Sternfeld, Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, Oakland CA.

Ellen B Gold, University of California Davis, Davis CA.

L Elaine Waetjen, University of California Davis, Davis CA.

Catherine Lee, Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, Oakland CA.

Lyndsay A Avalos, Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, Oakland CA.

Samar R El Khoudary, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA.

Monique M Hedderson, Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, Oakland CA.

References

- [1].Matthews KA, Crawford SL, Chae CU, Everson-Rose SA, Sowers MF, Sternfeld B, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Are changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors in midlife women due to chronological aging or to the menopausal transition?, Journal of the American College of Cardiology 54(25) (2009) 2366–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Matthews KA, Gibson CJ, El Khoudary SR, Thurston RC, Changes in cardiovascular risk factors by hysterectomy status with and without oophorectomy: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62(3) (2013) 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rader DJ, Hovingh GK, HDL and cardiovascular disease, Lancet 384(9943) (2014) 618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Soran H, Dent R, Durrington P, Evidence-based goals in LDL-C reduction, Clinical research in cardiology : official journal of the German Cardiac Society 106(4) (2017) 237–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].El Khoudary SR, HDL and the menopause, Curr Opin Lipidol 28(4) (2017) 328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].El Khoudary SR, Ceponiene I, Samargandy S, Stein JH, Li D, Tattersall MC, Budoff MJ, HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) Metrics and Atherosclerotic Risk in Women, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 38(9) (2018) 2236–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chin SH, Kahathuduwa CN, Binks M, Physical activity and obesity: what we know and what we need to know, Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 17(12) (2016) 1226–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Aune D, Norat T, Leitzmann M, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ, Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis, European journal of epidemiology 30(7) (2015) 529–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wahid A, Manek N, Nichols M, Kelly P, Foster C, Webster P, Kaur A, Friedemann Smith C, Wilkins E, Rayner M, Roberts N, Scarborough P, Quantifying the Association Between Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Journal of the American Heart Association 5(9) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Diaz KM, Shimbo D, Physical activity and the prevention of hypertension, Current hypertension reports 15(6) (2013) 659–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sofi F, Capalbo A, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Physical activity during leisure time and primary prevention of coronary heart disease: an updated meta-analysis of cohort studies, European journal of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation : official journal of the European Society of Cardiology, Working Groups on Epidemiology & Prevention and Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology 15(3) (2008) 247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sattelmair J, Pertman J, Ding EL, Kohl HW 3rd, Haskell W, Lee IM, Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis, Circulation 124(7) (2011) 789–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Howard VJ, McDonnell MN, Physical activity in primary stroke prevention: just do it!, Stroke 46(6) (2015) 1735–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Diep L, Kwagyan J, Kurantsin-Mills J, Weir R, Jayam-Trouth A, Association of physical activity level and stroke outcomes in men and women: a meta-analysis, Journal of women’s health (2002) 19(10) (2010) 1815–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mora S, Cook N, Buring JE, Ridker PM, Lee IM, Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events: potential mediating mechanisms, Circulation 116(19) (2007) 2110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kraus WE, Houmard JA, Duscha BD, Knetzger KJ, Wharton MB, McCartney JS, Bales CW, Henes S, Samsa GP, Otvos JD, Kulkarni KR, Slentz CA, Effects of the amount and intensity of exercise on plasma lipoproteins, N Engl J Med 347(19) (2002) 1483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fahlman MM, Boardley D, Lambert CP, Flynn MG, Effects of endurance training and resistance training on plasma lipoprotein profiles in elderly women, The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 57(2) (2002) B54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Thune I, Njolstad I, Lochen ML, Forde OH, Physical activity improves the metabolic risk profiles in men and women: the Tromso Study, Archives of internal medicine 158(15) (1998) 1633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Abdulnour J, Doucet E, Brochu M, Lavoie JM, Strychar I, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Prud’homme D, The effect of the menopausal transition on body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors: a Montreal-Ottawa New Emerging Team group study, Menopause (New York, N.Y.) 19(7) (2012) 760–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Polotsky HN, Polotsky AJ, Metabolic implications of menopause, Seminars in reproductive medicine 28(5) (2010) 426–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sowers M, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, A multicenter, multiethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition, in: Lobo R, Kelsey J, Marcus R (Eds.), Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology, Academic Press, San Diego CA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ainsworth BE, Sternfeld B, Richardson MT, Jackson K, Evaluation of the kaiser physical activity survey in women, Medicine and science in sports and exercise 32(7) (2000) 1327–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sternfeld B, Ainsworth BE, Quesenberry CP, Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women, Prev Med 28(3) (1999) 313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Steiner P, Freidel J, Bremner W, Stein E, Standardization of Micromethods for Plasma Cholesterol, Triglyceride, and HDL-Cholesterol with the Lipid Clinics’ Methodology, J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 19 (1981) 850. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Warnick GR, Albers JJ, A comprehensive evaluation of the heparin-manganese precipitation procedure for estimating high density lipoprotein cholesterol, Journal of lipid research 19(1) (1978) 65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Izawa S, Okada M, Matsui H, Horital Y, A New Direct Method for Measuring HDL-Choleterol, which does not Produce any Biased Results, J Med Pharm Sci 37 (1997) 1385–1388. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS, Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge, Clinical chemistry 18(6) (1972) 499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].N.C.f.H.S.V.a.H.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Plan and Operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-94, Washington DC, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ferris B, Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society), American Review of Respiratory Disease 118 (1978) 1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Block G, Thompson F, Hartman A, Larkin F, Guire K, Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1-year period, J Am Dietet Assn (92) (1992) 686–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gold EB, Eskenazi B, Lasley BL, Samuels SJ, O’Neill Rasor M, Overstreet JW, Schenker MB, Epidemiologic methods for prospective assessment of menstrual cycle and reproductive characteristics in female semiconductor workers, American journal of industrial medicine 28(6) (1995) 783–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Matthews KA, Meilahn E, Kuller LH, Kelsey SF, Caggiula AW, Wing RR, Menopause and risk factors for coronary heart disease, N Engl J Med 321(10) (1989) 641–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kuller LH, Matthews KA, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Edmundowicz D, Bunker CH, Coronary and aortic calcification among women 8 years after menopause and their premenopausal risk factors : the healthy women study, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 19(9) (1999) 2189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].About, About Adult BMI: How is BMI calculated and interpreted?, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#Interpreted. (Accessed October 3, 2014.

- [35].Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies, Lancet 363(9403) (2004) 157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jones B, Nagin D, Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them, Sociological Methods & Research 35(4) (2007) 542–571. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jones B, Nagin D, Roeder K, A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories, Sociological Methods & Research 29(3) (2001) 374–393. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nagin DS, Jones BL, Passos VL, Tremblay RE, Group-based multi-trajectory modeling, Statistical methods in medical research 27(7) (2018) 2015–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nagin DS, Group-Based Modeling of Development, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [40].El Khoudary SR, Wang L, Brooks MM, Thurston RC, Derby CA, Matthews KA, Increase HDL-C level over the menopausal transition is associated with greater atherosclerotic progression, Journal of clinical lipidology 10(4) (2016) 962–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].de Kat AC, Dam V, Onland-Moret NC, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, van der Schouw YT, Unraveling the associations of age and menopause with cardiovascular risk factors in a large population-based study, BMC medicine 15(1) (2017) 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].O’Keeffe LM, Kuh D, Fraser A, Howe LD, Lawlor D, Hardy R, Age at period cessation and trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors across mid and later life, Heart (British Cardiac Society) 106(7) (2020) 499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Keidar S, Bogner I, Gamliel-Lazarovich A, Leiba R, Fuhrman B, Kouperberg E, High plasma high-density lipoprotein levels, very low cardiovascular risk profile, and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women, Journal of clinical lipidology 3(5) (2009) 345–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Woodard GA, Brooks MM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Mackey RH, Matthews KA, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Lipids, menopause, and early atherosclerosis in Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Heart women, Menopause (New York, N.Y.) 18(4) (2011) 376–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fan AZ, Dwyer JH, Sex differences in the relation of HDL cholesterol to progression of carotid intima-media thickness: the Los Angeles Atherosclerosis Study, Atherosclerosis 195(1) (2007) e191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones D, Lopez-Pajares N, Ndumele CE, Orringer CE, Peralta CA, Saseen JJ, Smith SC Jr., Sperling L, Virani SS, Yeboah J, 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Circulation 139(25) (2019) e1082–e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bansal S, Buring JE, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks FM, Ridker PM, Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women, Jama 298(3) (2007) 309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mascarenhas-Melo F, Sereno J, Teixeira-Lemos E, Ribeiro S, Rocha-Pereira P, Cotterill E, Teixeira F, Reis F, Markers of increased cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women: focus on oxidized-LDL and HDL subpopulations, Disease markers 35(2) (2013) 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Paik JK, Chae JS, Kang R, Kwon N, Lee SH, Lee JH, Effect of age on atherogenicity of LDL and inflammatory markers in healthy women, Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases : NMCD 23(10) (2013) 967–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Owens JF, Matthews KA, Raikkonen K, Kuller LH, It is never too late: change in physical activity fosters change in cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged women, Preventive cardiology 6(1) (2003) 22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Costa RR, Pilla C, Buttelli ACK, Barreto MF, Vieiro PA, Alberton CL, Bracht CG, Kruel LFM, Water-Based Aerobic Training Successfully Improves Lipid Profile of Dyslipidemic Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Res Q Exerc Sport 89(2) (2018) 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Costa RR, Buttelli ACK, Coconcelli L, Pereira LF, Vieira AF, Fagundes AO, Farinha JB, Reichert T, Stein R, Kruel LFM, Water-Based Aerobic and Resistance Training as a Treatment to Improve the Lipid Profile of Women With Dyslipidemia: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Journal of physical activity & health 16(5) (2019) 348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zhang J, Chen G, Lu W, Yan X, Zhu S, Dai Y, Xi S, Yao C, Bai W, Effects of physical exercise on health-related quality of life and blood lipids in perimenopausal women: a randomized placebo-controlled trial, Menopause (New York, N.Y.) 21(12) (2014) 1269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Owens JF, Matthews KA, Wing RR, Kuller LH, Physical activity and cardiovascular risk: a cross-sectional study of middle-aged premenopausal women, Prev Med 19(2) (1990) 147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.