To the Editor:

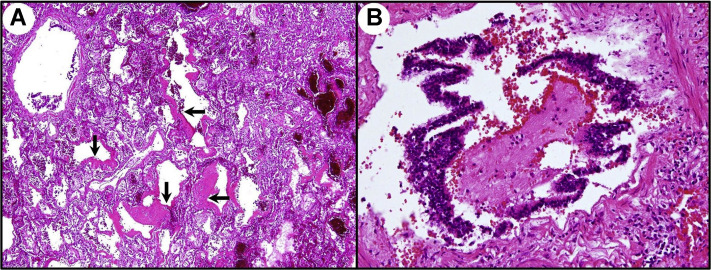

The interesting paper by Castiglioni and colleagues1 about COVID-19 pneumatocele merits some pathophysiologic deepening. In COVID-19, the respiratory acini, infiltrated by inflammatory cells, become edematous and progressively disventilated, which corresponds to ground glass opacities evolving toward dense consolidations on histopathology (Figure 1A). Alveoli and respiratory bronchioles are clogged by exudates and inflammatory cells, acting as plugs or implementing a “ball-valve” mechanism (Figure 1B). Consequently, their inner pressure, mainly after occlusion of Kohn interalveolar pores, progressively increases with peaks in the expiratory phase. The acinar microvessels, already affected by endotheliitis, easily undergo transformation to thrombosis, favored by a hypercoagulative milieu, in particular if overloaded by aggregates of platelets de novo generated by activated lung-resident megakaryocytes.2, 3, 4 This leads to areas of ischemia in the more peripheral airways, not provided with any cartilage support and paradoxically submitted to high airflow barotraumas. Microscopic bullae of interstitial emphysema, but sometimes also proper air leaks, are visible when of adequate size on computed tomography images as fine lucency bands. Moreover, through “corridors” dissected along the peribronchial/vascular sheaths, they can progress until the mediastinum, generating pneumomediastinum (Macklin effect), the pleura, causing pneumothorax, or rarely, the subpleural space, producing pneumatocele if contained by preexisting or acquired pleural/subpleural zones of fibrosis.1 , 5 Practically, this cascade of pathologic events alerts us to carefully monitor the patient's mechanical respiratory assistance in cases of COVID-19.

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia histopathology. (A) Diffuse alveolar damage with hyaline membranes, indicated by black arrows (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×50). (B) Obstructing bronchiolitis with exudative plug (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×200).

References

- 1.Castiglioni M., Pelosi G., Meroni A., et al. Surgical resections of superinfected pneumatoceles in a COVID-19 patient. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111:e23–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P., et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roncati L., Ligabue G., Nasillo V., et al. A proof of evidence supporting abnormal immunothrombosis in severe COVID-19: naked megakaryocyte nuclei increase in the bone marrow and lungs of critically ill patients. Platelets. 2020;31:1085–1089. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2020.1810224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roncati L., Gallo G., Manenti A., et al. Renin-angiotensin system: the unexpected flaw inside the human immune system revealed by SARS-CoV-2. Med Hypotheses. 2020;140:109686. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wintermark M., Schnyder P. The Macklin effect: a frequent etiology for pneumomediastinum in severe blunt chest trauma. Chest. 2001;120:543–547. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.2.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]