Abstract

Background: Smoking was among the top contributors to deaths and disability as the prevalence among male adults remains high, and that among male youth increases in Indonesia. While local studies have shown high visibility of outdoor tobacco advertising around schools, the country still has no outdoor tobacco advertising ban. Objective: To examine the association between youth smoking behavior and measures of outdoor tobacco advertising density and proximity in Indonesia. Methods: We combined two primary data sources, including outdoor tobacco advertising and smoking behavior among male youth in Semarang city. We randomly selected and interviewed 400 male students at 20 high schools in the city. In addition, we interviewed 492 male adults who lived near the schools for comparison. Results: We found significant associations between smoking use among youth (but not among adults) and measures of outdoor tobacco advertising density and proximity in Semarang city. Youth at schools with medium and high density of outdoor tobacco advertising were up to 2.16 times more likely to smoke, compared to those with low density. Similarly, youth at senior high schools with proximity to outdoor tobacco advertising were 2.8 times more likely to smoke. Also, young people at poorer-neighborhood schools with a higher density of and proximity to outdoor tobacco advertising were up to 5.16 times more likely to smoke. Conclusions: There were significant associations between smoking use among male youth (but not among male adults) and measures of outdoor tobacco advertising density and proximity in Indonesia. This highlights the need to introduce an outdoor tobacco advertising ban effectively, at least near schools.

Keywords: adolescent, smoking, tobacco, advertising, built environment, Indonesia

1. Introduction

Smoking was among the top contributors to deaths and disability, particularly among men, as shown by the latest Indonesian Global Burden of Study 2017 [1]. The prevalence of smoking among men (15+ years) and boys (13–14 years) was among the highest in the world at 67% (2018) and 36% (2014), respectively [2,3]. Despite all this, the country is still not among the 181 signatories of the Framework Convention of Tobacco Control. In effect, tobacco control efforts are lacking. There is one flagship smoke-free policy that was enacted in 2012 to ban tobacco smoking, advertising, promotion, and sale in selected facilities. However, it has been adopted only by two-thirds of 514 districts by 2018, with the compliance rates ranging from 17% in Jayapura to 78% in Bogor [4,5].

In addition, there is still no national regulation to ban outdoor tobacco advertising. As a consequence, previous studies have shown high visibility of outdoor tobacco advertising around schools in Indonesia. In 2015, a study in five cities found that tobacco billboards were visible from the gate in 32% of 360 sampled high schools [6]. In 2017, a survey of tobacco advertisements and promotions around schools in ten cities (including Semarang) found aggressive marketing strategies by showing brands and very low prices [7]. In 2018, our previous study found a total of 3453 advertisements throughout Semarang city, of which 74% were within a 5–10 min walk from schools [8].

Previous studies from high-income countries have shown that youth are highly receptive to tobacco advertising and that young people exposed to tobacco advertising and promotion are more likely to smoke [9,10,11,12,13]. However, studies on whether outdoor tobacco advertising visibility is associated with smoking behavior among youth is currently lacking in Indonesia and other developing countries [14]. Thus, our study aims to examine the association between youth smoking behavior and measures of outdoor tobacco advertising density and proximity in Indonesia, a lower-middle-income country.

The capital of Central Java province, Semarang city, hosted nearly 1.8 million people in 2018. The city government introduced the smoke-free policy since 2013 but has not been implementing more comprehensive tobacco control measures, including an outdoor tobacco advertising ban. This is partly due to the very high tobacco industry interference from 110 tobacco manufacturers in the province, including PT. Djarum and PT. Gudang Garam, with about 40% of cigarette sales nationally [8].

2. Methods

We employed a cross-sectional quantitative study to examine the association between youth smoking behavior and measures of outdoor tobacco advertising density and proximity in Indonesia. We used two primary data sources: outdoor tobacco advertising and smoking behavior among youth and adults in Semarang city. First, the advertising data were from our previous study conducted during November–December 2018 through a survey of outdoor tobacco advertisements. The types of advertisements included billboard, videoboard, banner, store sign, neon box, poster or sticker. There were 3453 outdoor tobacco adverts (including those in front of stores/retailers) with the size ranging from small (between 21 × 30 cm [approximately A4 size]) and 1.3 × 1.9 m) to large (>2.0 × 2.5 m [the size of a typical billboard]). The study also analyzed school data of 978 governmental and private schools in Semarang city, obtained from the city education office on 15 May 2019 (http://disdik.semarangkota.go.id (accessed on 11 December 2020)). In addition to school names and levels (primary, junior high, and senior high), data included addresses that we converted into geocodes using Google Sheets and geocoding add-ons. Further details on methods and results have been published elsewhere [8]. Second, as a follow-up from our previous study [8], we interviewed students of a sample of high schools to observe smoking behavior, defined as ever smoked cigarettes. We randomly selected 20 high schools and interviewed 400 male students (or 20 in each school). For sample calculation, we used Indonesian Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) data that 50% of youth reported seeing cigarette advertisement or promotion and 5% margin of error, resulting in a minimum sample of 384 students. The inclusion criteria included male, at least 13 years old, at least one year at the junior or senior high school, and willing to be a participant. For comparison, we also interviewed male adults near each school where we randomly selected about 24 adults with the inclusion criteria of male, at least 18 years old, live near the schools, and willing to be a participant.

In this study, we focused on males because of having disproportionately higher smoking prevalence in Indonesia. Smoking prevalence was 10.2% vs. 0.2% among boys and girls (13–14 years old) and 61.4% vs. 2.3% among men and women (15+ years old) in 2018 [15]. In terms of study instruments, we used adaptations of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) and Global Tobacco Adult Survey (GATS) questionnaires from the Ministry of Health (both in the Indonesian language). Data collection was conducted by 11 trained enumerators during September to December 2019. Ethical clearance was obtained from the State University of Semarang (Number: 242/KEPK/EC/2019).

We conducted two types of data analysis: geospatial analysis and quantitative analysis. The geospatial analyses were conducted in ArcMap 10.6. We employed the geoprocessing buffer tool to generate buffers of 200 and 400 m around each school. We used two measures of exposure: density and proximity of advertising. Density was measured by the total number of adverts within 400 m of each school, which we evenly divided into low (0–5 adverts), medium (6–14 adverts), and high (15+ adverts). Proximity was measured by the presence of at least one outdoor tobacco advert within 200 m of school [16,17]. We also used the spatial intersect and join tools to calculate the number of adverts within each buffer. We then matched the exposure results with the binary dependent variable of ever smoking. The quantitative analyses were conducted in STATA 15.1 and employed multiple logit regressions. We produced odds ratios for comparing smoking prevalence between medium-to-low exposure and high-to-low exposure, controlling for age. We also provided subgroup analysis by school level (junior and senior high school) and neighborhood characteristics (poorer and richer areas). For the latter, using data on subdistrict-level poverty rates from the City Statistics Bureau, we used -xtile- command in STATA 15.1 to group the districts (and any schools within) into two groups: poorer and richer areas.

3. Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of the youth and adult samples and outdoor tobacco advertising.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of youth and adult samples (all males) and outdoor tobacco advertising.

| Youth Sample | Adult Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | Variable | n | % |

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | ||

| Total | 400 | 492 | |||

| Age group | Age group | ||||

| 11–14 years | 190 | 48% | 18–34 years | 232 | 47% |

| 15–21 years | 210 | 53% | 35+ years | 260 | 53% |

| Level | Neighborhood | ||||

| Junior high school | 260 | 65% | Poorer area | 223 | 45% |

| Senior high school | 140 | 35% | Richer area | 269 | 55% |

| Neighborhood | Advert density exposure | ||||

| Poorer area | 180 | 45% | Low | 197 | 40% |

| Richer area | 220 | 55% | Medium | 147 | 30% |

| High | 148 | 30% | |||

| Advert density exposure | |||||

| Low | 160 | 40% | Advert proximity exposure | ||

| Medium | 120 | 30% | At least one within 200 m | 292 | 59% |

| High | 120 | 30% | No advert within 200 m | 200 | 41% |

| Advert proximity exposure | Smoking status | ||||

| At least one within 200 m | 240 | 60% | Ever smoke cigarette | 354 | 72% |

| No advert within 200 m | 160 | 40% | Otherwise | 138 | 28% |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Ever smoke cigarette | 258 | 65% | |||

| Otherwise | 142 | 36% | |||

Note: n = sample, % = proportion. There were 400 students interviewed from 20 high schools (so 20 students per school). Out of 400 youth samples, 382 students were 11–17 years old, 14 students were 18 years old, and 4 students were 19 or 21 years old. There were 492 adults interviewed near those 20 high schools (24–25 adults per school). For neighborhood, poorer/richer areas are with higher/lower subdistrict-level poverty rates. The measures of density and proximity were the same for youth/students and adult samples. Density was measured by the total number of adverts within 400 m of each school. For density, basic descriptive = mean 9.75, standard deviation 7.97, and range 0–24.

We analyzed a total of 892 individuals, including 400 youth and 492 adults. Forty-eight percent of youth were 11–14 years old, and 47% of adults we 18–34 years old. Among the youth sample, 65% and 35% were in junior and senior high schools, respectively. Forty-five percent of youth went to schools, and 45% of adults lived in poorer areas. In terms of outdoor tobacco advertising, only 40% of youth and adults were exposed to a low density of advert, while the other 60% were exposed to medium and high density. In terms of smoking behavior, 65% of the youth sample reported ever smoke cigarettes, while 72% of the adult sample did.

Table 2 shows the association between smoking behavior among youth and adults and measures of outdoor tobacco advert density and proximity.

Table 2.

Association between smoking behavior among youth and adults and measures of outdoor tobacco advert density and proximity in Semarang, Indonesia.

| Youth Sample | Adult Sample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density | Proximity | Density | Proximity | |||||

| OR (SE) | OR (SE) | OR (SE) | OR (SE) | |||||

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | |||||

| (a) Overall | n = 400 | n = 492 | ||||||

| Density tertiles | ||||||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Medium | 1.93 ** | (0.52) | 1.25 | (0.31) | ||||

| High | 2.16 ** | (0.59) | 1.01 | (0.24) | ||||

| Proximity | ||||||||

| At least one within 200 m | 0.97 | (0.22) | 0.95 | (0.20) | ||||

| (b) Junior high schools | n = 260 | |||||||

| Density tertiles | ||||||||

| Low | Ref | NA | ||||||

| Medium | 1.76 | (0.54) | ||||||

| High | 1.93 ** | (0.64) | ||||||

| Proximity | ||||||||

| At least one within 200 m | 0.68 | (0.18) | ||||||

| (c) Senior high schools | n = 140 | |||||||

| Density tertiles | ||||||||

| Low | Ref | NA | ||||||

| Medium | 2.83 | (1.58) | ||||||

| High | 2.78 ** | (1.38) | ||||||

| Proximity | ||||||||

| At least one within 200 m | 2.80 ** | (1.23) | ||||||

| (d) Poorer areas | n = 180 | n = 223 | ||||||

| Density tertiles | ||||||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Medium | 2.64 ** | (0.89) | 1.66 | (0.55) | ||||

| High | 5.16 ** | (3.00) | 0.96 | (0.46) | ||||

| Proximity | ||||||||

| At least one within 200 m | 2.03 ** | (0.64) | 1.70 | (0.53) | ||||

| (e) Richer areas | n = 220 | n = 269 | ||||||

| Density tertiles | ||||||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Medium | 0.99 | (0.60) | 0.79 | (0.30) | ||||

| High | 1.01 | (0.37) | 0.94 | (0.29) | ||||

| Proximity | ||||||||

| At least one within 200 m | 0.19 ** | (0.08) | 0.55 | (0.18) | ||||

Note: OR = Odds Ratio, SE = Standard Errors, n = Sample, Ref = Reference group. Odds ratios were obtained from logit regressions of smoking status on density/proximity, controlling for age (in STATA 15.1). There were 400 students interviewed from 20 high schools; 492 adults interviewed near those schools. The measures of density and proximity were the same for youth and adults. Density was measured by the total number of adverts within 400 m of each school. For neighborhood, poorer/richer areas are with higher/lower subdistrict-level poverty rates. The density was 1.43 times higher at schools in richer (mean = 11.27, SD = 8.29) areas than those in poorer areas (mean = 7.89, SD = 7.14). ** = significant at 5% level.

In terms of density, the odds of smoking among youth were significantly higher up to 2.16 times at schools with medium and high density, compared to that with low density (Table 2 panel a column 1). However, the odds of smoking among adults were not statistically different (Table 2, panel a, column 2). By the school level, the odds of youth smoking were significantly higher up to 2.78 times at junior and senior high schools with high advert density, compared to that with low density (Table 2, panels b–c, column 1). By neighborhood, the odds of youth smoking were significantly higher up to 5.16 times at schools with medium and high density in poorer areas, but not in richer areas (Table 2, panels d–e, column 1). Among adults, the odds of smoking were not statistically different by density tertiles, both in poorer and richer areas (Table 2 panels d–e column 2).

In terms of proximity, the odds of youth smoking were not statistically different between students at schools with at least one advert within 200 m (proximity) and those at schools with no advert within 200 m (Table 2, panel a, column 2). Those odds, however, were significantly higher 2.80 times among students at senior high schools and 2.03 times among students at poorer schools with proximity, compared to otherwise (Table 2, panels b–e, column 2). Among adults, the odds of smoking were not statistically different by proximity both overall and by neighborhood area (Table 2, panels d–e, column 4).

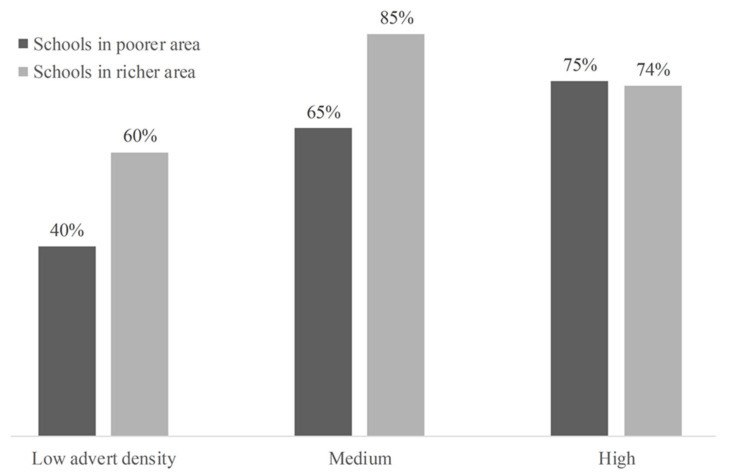

Figure 1 further investigates youth smoking and advert density by neighborhood characteristics.

Figure 1.

Smoking prevalence among youth and outdoor tobacco advertising density by neighborhood characteristics.

First, smoking prevalence was higher at schools with medium and high advert density than those with low advert density—the average smoking prevalence was 50% at schools with low density and 75% at those with medium and high density (The results in Table 2 confirmed this). Second, smoking prevalence was higher among students at richer schools, relative to those at poorer schools, but only if the schools had low-to-medium density. The smoking prevalence among students at richer and poorer schools was similar among the schools with high advert density.

4. Discussion

Our study showed significant associations between cigarette smoking among youth (but not among adults) and measures of outdoor tobacco advertising density and proximity in Semarang city. Youth at schools with medium and high density of outdoor tobacco advertising were up to 2.16 times more likely to smoke, compared to those with low density. Similarly, youth at senior high schools with proximity (i.e., at least one advert within 200 m) to outdoor tobacco advertising were 2.8 times more likely to smoke. Also, youth at poorer-neighborhood schools with a higher density of and proximity to outdoor tobacco advertising were up to 5.16 times more likely to smoke.

These results align with previous studies from other countries [9,10,11,12,13]. From high-income countries, a Cochrane study reviewed 19 studies in the USA, UK, Germany, and Spain and found that the nonsmoking adolescents who were more aware of tobacco advertising, were more likely to have experimented with cigarettes or become smokers [10]. Further, a study in the United States showed that neighborhoods with the highest proportion of Black or lower-income residents had 2.84 times greater exterior advertisement [18]. From low- and middle-income countries, a study in India showed that smoking use among youth at schools with a high density of outdoor tobacco advertising was more than doubled, compared to those at low density [14].

These findings are significant for at least three reasons. First, there are over 400 high schools in Semarang city alone [8], indicating potential exposure to tobacco advertising for many young people. A study among students in Scotland showed that 80% of nearly 1500 students recalled seeing tobacco advertising at stores [19]. Second, these findings complement our previous study on high outdoor tobacco advertising visibility near schools in the city [8]. This suggests that students are more likely to initiate smoking experimentally either from peer pressure (‘If I don’t smoke, I’m not a real man’) [20] or from encouragement to smoke by advertising [21]. Third, the lack of an outdoor tobacco advertising ban would potentially increase the disparity in youth smoking as our findings show doubling odds ratio among poorer-neighborhood schools. Learning from a study on cigarette retailers in the United States showed that banning tobacco product sales near schools may reduce the density in lower-income neighborhoods compared to higher-income ones [22].

For policy, our findings support for introducing a national outdoor tobacco advertising ban in Indonesia and other developing countries that have not done so. An effective outdoor tobacco advertising ban in Greece has shown to reduce the number of advertising to zero [23], which means elimination of advertising exposure to young people. Hopefully, the government will be able to overcome the huge tobacco company interference and introduce an outdoor tobacco advertising ban, along with other comprehensive MPOWER measures [24]. All this indicates the need to implement the measures of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) to help reduce or eliminate the tobacco advertising including near schools.

Our study has several limitations. First, due partly to limited funding resource, this current study was conducted one year after the first study on outdoor tobacco advertising locations. We argue that the adverts did not change much as there were no major tobacco efforts in the city during the period. Studies in nearby Banyuwangi city, which was also lacking a total advertising ban, showed similarly higher density of outdoor tobacco adverts around schools between 2018 and 2019 [25,26]. Second, our study was conducted in an urban setting, so findings should not be representative of the whole country. Further study should examine rural districts to explore any regional and socioeconomic variations Also, the study used male sample only, which limits generalization to all gender. Third, our study only interviewed junior and senior high school students. With data showing that smoking initiation is getting younger in the country, further studies should also assess smoking behavior among primary school students. Lastly, our findings identified associations not causations, because of the possible endogenous nature of where outdoor advertising is placed and therefore the endogenous nature of advertising exposure. While these data are consistent with the suggestion that a ban on outdoor advertising might reduce smoking, further study should deal more effectively with the possible endogenous nature of outdoor advertising placement. One could try to examine changes in advertising exposure and changes in smoking behavior for those in the same area. One could also compare youth from the same school but whose commuting path intersects with different levels of outdoor advertising or find some other design (e.g., a diff-in-diff model) that provides a more exogenously determined treatment and control group. Despite all this, our findings have important policy implications for Indonesia and beyond.

5. Conclusions

There were significant associations between smoking use among youth (but not among adults) and measures of outdoor tobacco advertising density and proximity in Indonesia. This highlights the need to introduce an outdoor tobacco advertising ban, at least near schools, effectively in Indonesia and beyond. While the findings are consistent with the suggestion that a ban on outdoor advertising might reduce smoking, further study should deal with the possible endogenous nature of outdoor advertising placement.

Acknowledgments

We thank participants of Research and Publication Colloquium at Faculty of Health Sciences Universitas Dian Nuswantoro for valuable suggestions.

Author Contributions

S.H., A.A. and D.K. conceived the study. S.H., E.R., K.K.S., Y.M.M., N. conducted data collection. S.H. and D.K. conducted data analysis. S.H. and D.K. drafted and E.R., K.K.S., Y.M.M., N. and A.A. provided inputs to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Support was provided by the Center for Islamic Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia, with funding awarded by Bloomberg Philanthropies to Johns Hopkins University. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of Bloomberg Philanthropies or Johns Hopkins University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of State University of Semarang (Number: 242/KEPK/EC/2019 Date: 11 October 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mboi N., Surbakti I.M., Trihandini I., Elyazar I., Smith K.H., Ali P.B., Kosen S., Flemons K., Ray S.E., Cao J., et al. On the road to universal health care in Indonesia, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392:581–591. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30595-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Factsheet 2018 Indonesia: Heart Disease and Stroke Are the Commonest Ways by which Tobacco Kills People. [(accessed on 17 March 2020)];2018 Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272673/wntd_2018_indonesia_fs.pdf?sequence=1.

- 3.Kusumawardani N., Rachmalina S., Wiryawan Y., Anwar A., Handayani K., Mubasyiroh R., Angraeni S., Nusa R., Cahyorini, Rizkianti A., et al. Global School Health Survey 2015 Indonesia Report: Risky Behavior among High School Students in Indonesia. World Health Organization; Jakarta, Indonesia: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahidin M., Hidayat M.S., Arasy R.A., Amir V., Kusuma D. Geographic distribution, socio-economic disparity and policy determinants of smoke-free policy adoption in Indonesia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2020;24:383–389. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.19.0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahyuti W., Hasairin S.K., Mamoribo S.N., Ahsan A., Kusuma D. Monitoring Compliance and Examining Challenges of a Smoke-free Policy in Jayapura, Indonesia. J. Prev. Med. Public Health. 2019;52:427. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.19.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Children Media Monitoring Foundation Beyond the School Gate: Bombarded by Cigarette Advertising. [(accessed on 7 March 2020)];2015 Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets/reports/Indonesia-Report.pdf.

- 7.Anak Y.L. Dark Picture of 10 Cities Surrounded by 2,868 Tobacco Advertisements. Jakarta, Indonesia: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nurjanah N., Manglapy Y.M., Handayani S., Ahsan A., Sutomo R., Dewi F.S.T., Chang P., Kusuma D. Density of tobacco advertising around schools. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2020;24:674–680. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.19.0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pierce J.P., Sargent J.D., Portnoy D.B., White M., Noble M., Kealey S., Borek N., Carusi C., Choi K., Green V.R., et al. Association Between Receptivity to Tobacco Advertising and Progression to Tobacco Use in Youth and Young Adults in the PATH Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:444. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lovato C., Watts A., Stead L.F. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011;2011:CD003439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilpin E.A., White M.M., Messer K., Pierce J.P. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and promotions among young adolescents as a predictor of established smoking in young adulthood. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97:1489–1495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) UK Tobacco Advertising and Promotion. [(accessed on 7 March 2020)];2019 Available online: http://ash.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Tobacco-Advertising-and-Promotion-download.pdf.

- 13.United States, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention, & Health Promotion (US), Office on Smoking . Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mistry R., Pednekar M., Pimple S., Gupta P.C., McCarthy W.J., Raute L.J., Patel M., Shastri S.S. Banning tobacco sales and advertisements near educational institutions may reduce students’ tobacco use risk: Evidence from Mumbai, India. Tob. Control. 2015;24:e100–e107. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hapsari D., Nainggolan O., Kusuma D. Hotspots and Regional Variation in Smoking Prevalence Among 514 Districts in Indonesia: Analysis of Basic Health Research 2018. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2020;12:1–32. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v12n10p32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henriksen L., Feighery E.C., Schleicher N.C., Cowling D.W., Kline R.S., Fortmann S.P. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Prev. Med. 2008;47:210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan D.T., Kawachi I., Subramanian S.V., Aldstadt J., Melly S.J., Williams D.R. Examination of How Neighborhood Definition Influences Measurements of Youths’ Access to Tobacco Retailers: A Methodological Note on Spatial Misclassification. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;179:373–381. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong A.Y., Queen T.L., Golden S.D., Ribisl K.M. Neighborhood disparities in the availability, advertising, promotion, and youth appeal of little cigars and cigarillos, United States, 2015. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22:2170–2177. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stead M., Eadie D., MacKintosh A.M., Best C., Miller M., Haseen F., Pearce J., Tisch C., Macdonald L., MacGregor A., et al. Young people’s exposure to point-of-sale tobacco products and promotions. Public Health. 2016;136:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng N., Weinehall L., Ohman A. ‘If I don’t smoke, I’m not a real man’—Indonesian teenage boys’ views about smoking. Health Educ. Res. 2007;22:794–804. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prabandari Y.S., Dewi A. How do Indonesian youth perceive cigarette advertising? A cross-sectional study among Indonesian high school students. Glob. Health Action. 2016;9:30914. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.30914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribisl K.M., Luke D.A., Bohannon D.L., Sorg A.A., Moreland-Russell S. Reducing Disparities in Tobacco Retailer Density by Banning Tobacco Product Sales Near Schools. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017;19:239–244. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vardavas C.I., Girvalaki C., Lazuras L., Triantafylli D., Lionis C., Connolly G.N., Behrakis P. Changes in tobacco industry advertising around high schools in Greece following an outdoor advertising ban: A follow-up study. Tob. Control. 2013;22:299–301. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assunta M., Dorotheo E.U. SEATCA Tobacco Industry Interference Index: A tool for measuring implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Tob. Control. 2016;25:313–318. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sebayang S.K., Dewi D.M.S.K., Lailiyah S.U., Ahsan A. Mixed-methods evaluation of a ban on tobacco advertising and promotion in Banyuwangi District, Indonesia. Tob. Control. 2019;28:651–656. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebayang S.K., Dewi D.M.S.K., Puspikawati S.I., Astutik E., Melaniani S., Kusuma D. Spatial analysis of outdoor tobacco advertisement around children and adolescents in Indonesia. Glob. Public Health. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1869800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon reasonable request.