Abstract

COVID-19 spurred a rapid rise in telemedicine, but it is unclear how use has varied by clinical and patient factors during the pandemic. We examined the variation in total outpatient visits and telemedicine use across patient demographics, specialties, and conditions in a database of 16.7 million commercially insured and Medicare Advantage enrollees from January to June 2020. During the pandemic, 30.1% of all visits were provided via telemedicine, and the weekly number of visits increase 23-fold compared to the pre-pandemic period. Telemedicine use was highest in communities with more minority residents (34.3% vs. 26.5% for enrollees residing in counties with lowest vs. highest quartiles of white race). Across specialties, the use of any telemedicine during the pandemic ranged from 68% of endocrinologists to 9% of ophthalmologists. Across common conditions, the percentage of visits provided during the pandemic via telemedicine ranged from 53% for depression to 3% for glaucoma. Higher rates of telemedicine use for common conditions were associated with smaller decreases in total weekly visits during the pandemic.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine use dramatically grew within a matter of weeks.1,2,3,4,5 After years of slow adoption,6 many clinicians used telemedicine for the first time to limit patient and staff exposure to the virus.7 This expansion was facilitated by temporary waivers of many telemedicine regulations and expanded reimbursement.8 For example, Medicare broadened telemedicine coverage to urban beneficiaries,9 states relaxed restrictions around telemedicine provider licensing,10 and many commercial insurers expanded reimbursement and waived copayments for telemedicine visits.11

While the increase in telemedicine use during the pandemic is widely recognized,12,13 it is unclear how use of telemedicine and in-person care has varied across patient demographics, clinical specialties, and medical conditions. There are concerns that increased use of telemedicine during the pandemic may exacerbate health disparities due to the “digital divide,” defined as the absence of broadband or smart phone technology necessary for video telemedicine visits among disadvantaged populations.14,15,16,17,18

There is also uncertainty on the clinical impact of the substantial drop in outpatient visits observed as COVID-19 swept across the country.19 Natural disasters, in which care may be interrupted for weeks or months, hamper chronic illness management and increase mortality over the long term.20,21 The long-term impact of the deferred care during the COVID-19 pandemic may depend on the conditions and specialties for which clinical volumes fell the most. A drop in overall visit volume may be mitigated by telemedicine use given that some conditions are more amenable to telemedicine than others. Evidence on how care has changed across different clinical conditions and specialties can help with targeting of resources to make up for months of deferred care.

To address these knowledge gaps, we analyzed data from 16.7 million individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance.22 We examined trends for in-person and telemedicine outpatient care in 2020 and how their use varied by patient demographics, specialties, and medical conditions.

STUDY DATA AND METHODS

Data Sources and Study Sample

Our study sample included de-identified claims for all outpatient visits over a 24-week period from January 1, 2020 to June 16, 2020 in the OptumLabs® Data Warehouse (OLDW). The OLDW includes medical claims and enrollment records for commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees.22 During the pandemic, UnitedHealthcare began reimbursing clinicians for audio-video visits at parity with in-person visits, waived cost sharing, and waived the “originating site” telemedicine requirements that had restricted use of telemedicine in the home and in urban areas for both Medicare Advantage and commercial plan enrollees.23 We combined this database with county-level characteristics from the U.S. Census and publicly available data on county-level COVID-19 incidence.24 We included all enrollees with 12 months of continuous medical enrollment in any plan from July 2019 through June 2020 and defined January 1-March 17, 2020 as the “pre-COVID-19” period (11 weeks) and March 18-June 16, 2020 as the “COVID-19” period (13 weeks). We chose March 18th to define the start of the COVID-19 period because Medicare announced expanded telehealth coverage on March 17, 2020.25

Classification of Outpatient Visits

In the COVID-19 period, Medicare significantly expanded the outpatient services that were eligible for telemedicine reimbursement. Many private insurers replicated these changes.26 We defined outpatient visits using Medicare’s expanded list of outpatient Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, excluding all CPT codes that were specific for clinical settings outside of clinician offices (e.g., emergency departments, hospital inpatient, nursing home or dialysis facility codes; see Appendix Exhibit 1 for full list).27 We identified both audio-video (modifier codes GT, GQ, or 95) and audio-only telemedicine visits (CPT codes 99441–99443).28,29 We classified all other outpatient visits as in-person visits. We chose not to compare use of audio-video vs. audio-only telemedicine visits because of ambiguities around coding telemedicine visits and concerns about under-coding of audio-only visits (see Appendix Exhibit 2 for more details).27

We also categorized outpatient visits by diagnostic codes and clinician specialty. We grouped visits into diagnosis categories using the primary diagnosis code listed and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) codes for ICD-10-CM diagnoses.30 We also categorized visits by clinician specialty using specialty designations defined by OptumLabs. Because of the large number of categories for clinician specialties (92 specialties) and diagnostic codes (499 diagnostic categories), in our main analyses we focused on the top quartile of diagnostic categories and top quartile of clinical specialties (including physicians and non-physician specialties) by volume during the COVID-19 period. These diagnostic categories and specialties accounted for the vast majority of all visits in the COVID-19 period (126 diagnostic categories accounting for 88% of visits in the COVID-19 period and 22 specialties accounting for 87% of visits in the COVID-19 period; Appendix Exhibit 1 for both lists).27

Enrollee Characteristics

We captured age (categorized into seven bins: 0–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–64 and 65 years and older), sex, rural-urban commuting area (RUCA), four-category U.S. Census designation,31 insurance type (commercial vs. Medicare Advantage), and enrollee county-level race and income indicators from the 2010 U.S. Census and county-level COVID-19 cases per capita on April 16, 2020. We selected April 16th as it was 30 days into the pandemic and COVID-19 burden early in the pandemic likely impacted telemedicine use. We divided county-level measures into quartiles (i.e., percentage with white/Caucasian, median household income, and COVID-19 cases per capita). Using the Elixhauser comorbidity index,32 we also captured the number of 29 comorbidities for each enrollee defined as at least 1 claim in any diagnostic field between July 2019 and December 2019 (prior to the study period).

Study Outcomes

We examined changes in telemedicine and total (telemedicine plus in-person) outpatient visit volume from the “pre-COVID” (January 1-March 17, 2020) to “COVID-19” (March 18-June 16, 2020) periods across the range of diagnosis categories, clinician specialties, and demographic characteristics described above. Specifically, within each diagnostic category, specialty, and demographic characteristic, we calculated the percent of total visits delivered by telemedicine, defined as the number of telemedicine visits divided by the number of total visits, in the COVID-19 period. We also calculated the percent change in total weekly visits (including both telemedicine and in-person visits) from the pre- to COVID-19 period, defined as the difference between the mean number of total visits per week in the pre- and COVID-19 periods divided by the pre-COVID period mean in each group. For telemedicine visits, we focused on the percent of total visits in the COVID-19 period alone rather than the change between the pre- to COVID-19 periods because telemedicine volume was consistently low for nearly all specialties in the pre-COVID period.

At the enrollee level, we captured whether individuals used any in-person or telemedicine services pre- or during COVID-19 and the number of those services. We also calculated the proportion of clinicians in each specialty delivering any outpatient care via telemedicine during the pre- and COVID-19 periods. The numerator for these proportions were clinicians billing for any outpatient telemedicine encounter in the given period. The denominator was the number of unique clinicians in each specialty billing for any outpatient service during the entire study period (“pre-COVID” and “COVID-19” periods). We used the entire study period to ensure we included clinicians who may have stopped providing care entirely after the pandemic began.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-squared tests to test for bivariate differences between the characteristics of enrollees using any telemedicine service during the pre and COVID-19 periods. To assess whether any demographic characteristics were independently associated with use of telemedicine and total outpatient care in the COVID-19 period, we fit four separate, enrollee-level Poisson regression models with outcomes of the mean number of telemedicine and total (telemedicine plus in-person) visits per week, expressed as weekly visits per 1,000 members, in the pre- and COVID-19 periods. Models included each enrollee characteristic as defined previously (Appendix Exhibit 1 for model specification).27 We fit the Poisson regression models using a random sample of 5% of all enrollees to facilitate model convergence given a study sample of nearly 17 million enrollees. Due to the strong correlation between age category and insurance type (r=0.95), we omitted insurance type from analyses to avoid collinearity. We also calculated average marginal effects for each explanatory variable using SAS 9.4.

Some of the most recent data in the OptumLabs database may be underpopulated because of the typical lag, of up to several weeks, between service delivery and the processing and reporting of medical claims.33,34 We tested the completeness of claims during each week of our study period by calculating the weekly rates of childbirths per 1,000 female enrollees between the ages of 15 and 44, based on the assumption that the rate of childbirths would remain stable despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The weekly rate of childbirths remained stable from January 1 until June 16, 2020 (see Appendix Exhibit 1 for analysis.27

Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. First, these findings may not generalize to other populations, such as those with traditional Medicare or Medicaid coverage. Second, our study period runs through June 16, 2020, providing only 13 weeks of COVID-19 data. As a result, our estimates of outpatient volume and telemedicine adoption may not reflect longer term trends. Third, despite our sensitivity analyses to assess completeness of data, recent data in our analysis (e.g., June 2020) may be underpopulated if lags in childbirth claims differ from lags in outpatient (telemedicine and in-person) visit claims. Consequently, we may be underestimating both telemedicine and in-person visits during the last weeks of the study period. Finally, we were unable to distinguish audio-video from audio-only telemedicine visits due to ambiguities around coding telemedicine visits and concerns about under-coding of audio-only visits.

STUDY RESULTS

Overall In-Person and Telemedicine Visits

There were 16,740,365 enrollees in our sample. 51.3% were female with a mean age of 44.5 and mean number of 0.80 chronic conditions (Exhibit 1). In the COVID-19 period, 30.1% of total visits were provided via telemedicine, with the weekly number of telemedicine visits increasing from 16,540 to 397,977 visits per week in the pre- to COVID-19 periods – a 23-fold increase in telemedicine use. Despite the increase, overall visit volume decreased by 35.0% (2,031,943 to 1,320,591 visits per week in the pre- and COVID-19 periods, respectively).

EXHIBIT 1:

Demographics of Telemedicine Users During the Pre- and COVID-19 periods, January 1, 2020 – June 16, 2020

| Total Study Population | Telemedicine Users | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire Study Period (Jan1-Jun16) |

Pre-COVID (Jan1-Mar17) |

COVID-19 (Mar18-Jun16) |

||

| Number of people | 16,740,365 | 146,035 | 2,891,387 | |

| Mean Age (years) | 44.5 | 38.4 | 51.8 | |

| Age | 0–19 | 17.3 | 12.4 | 9.2 |

| 20–29 | 12.1 | 15.6 | 8.7 | |

| 30–39 | 13.1 | 26.5 | 11.5 | |

| 40–49 | 13.2 | 20.2 | 12.9 | |

| 50–59 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 15.7 | |

| 60–64 | 6.7 | 4.9 | 8.5 | |

| 65+ | 23.5 | 5.5 | 33.5 | |

| Gender | Male | 48.7 | 36.9 | 41.5 |

| Female | 51.3 | 63.1 | 58.5 | |

| Insurance Type | Commercial | 78.5 | 94.6 | 67.2 |

| Medicare Advantage | 21.5 | 5.4 | 32.8 | |

| Urban/Rural Designation | Urban | 87.7 | 91.3 | 89.7 |

| Large Rural | 6.7 | 5.1 | 5.9 | |

| Small Rural | 3.5 | 2.4 | 2.8 | |

| Rural Isolated | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.6 | |

| County Median Household Income, Quartile | 1 (Low) | 31.7 | 30.6 | 32.8 |

| 2 | 26.1 | 26.2 | 25.2 | |

| 3 | 23.3 | 26.8 | 23.6 | |

| 4 (High) | 18.8 | 16.4 | 18.4 | |

| County % White/Caucasian Individuals, Quartile | 1 (Low) | 19.1 | 24.0 | 19.7 |

| 2 | 28.5 | 34.2 | 30.2 | |

| 3 | 26.9 | 24.2 | 26.9 | |

| 4 (High) | 25.5 | 17.7 | 23.2 | |

| Census Division | New England | 4.4 | 2.9 | 6.8 |

| Middle Atlantic | 9.8 | 10.2 | 12.6 | |

| East North Central | 16.3 | 11.5 | 15.5 | |

| West North Central | 11.2 | 7.7 | 8.9 | |

| South Atlantic | 24.3 | 23.2 | 25.1 | |

| East South Central | 4.5 | 3.3 | 3.8 | |

| West South Central | 13.4 | 21.8 | 12.8 | |

| Mountain | 8.3 | 10.2 | 7.3 | |

| Pacific | 7.8 | 9.3 | 7.2 | |

| Mean Number of Chronic Illnesses | 0.80 | 0.71 | 1.59 | |

Authors’ analysis of data from OptumLabs Data Warehouse

All univariate comparisons between telemedicine users vs. non-users are statistically significant by chi-squared test or t-test at p<0.001. Urban-Rural designations are based on USDA’s four category classification.

In-Person and Telemedicine Visits by Patient Demographics

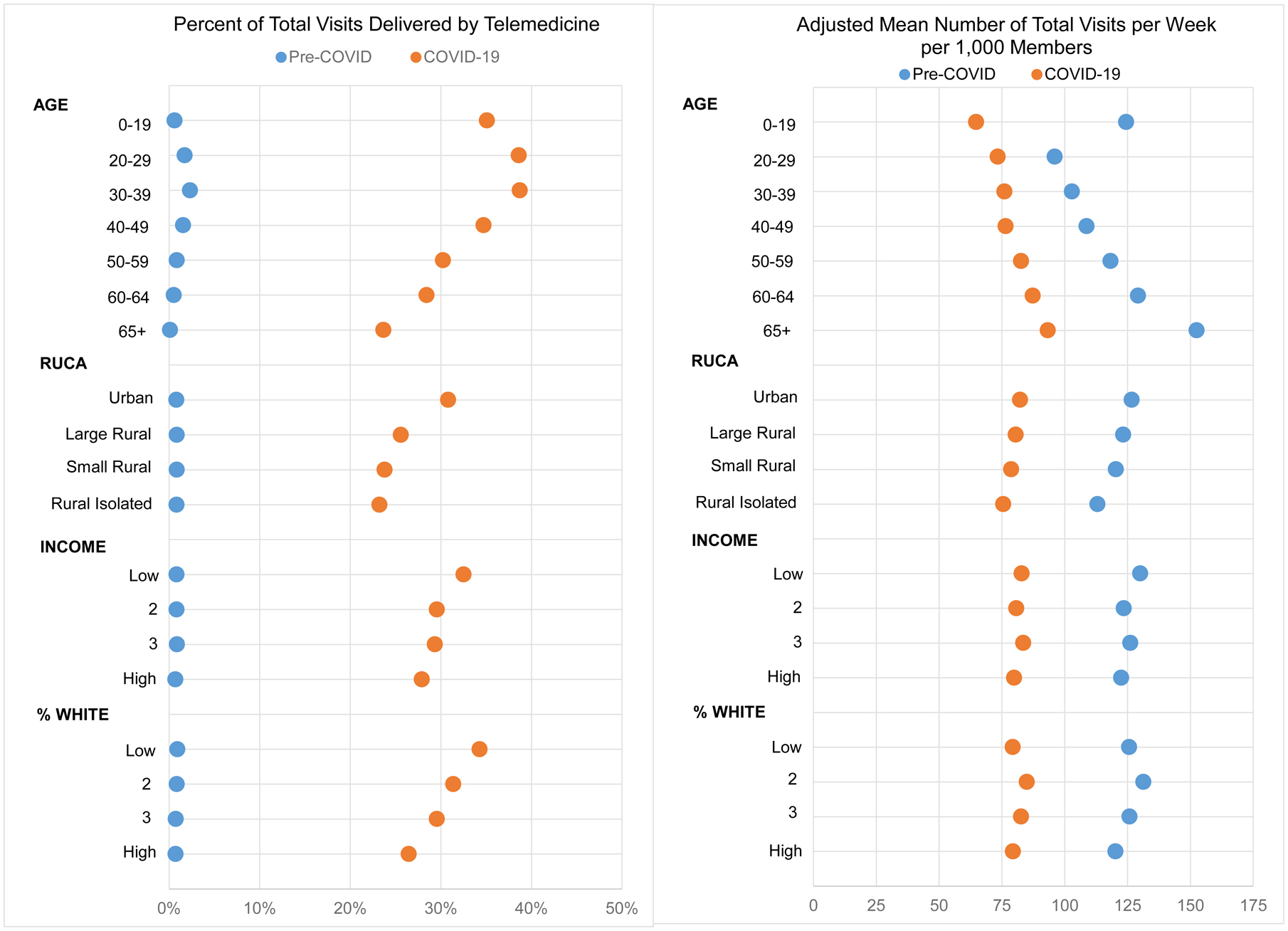

In the COVID-19 period, the percentage of total visits provided via telemedicine was smallest among those aged 65+ (23.7% among 65+ vs. 38.7% among 30–39 years old, p<0.001 for all differences in telemedicine use by each age category in the COVID-19 period; Exhibit 1, Appendix Exhibits 3 and 4).27

Enrollees in counties with the lowest quartile of median household income and proportion white race had a greater percentage of total visits delivered via telemedicine in the COVID-19 period compared to those in the highest quartiles (31.9% vs. 27.9% for lowest and highest quartiles of median income, p<0.001; 33.2% vs. 27.7% for lowest and highest quartiles of white race, p<0.001) (Exhibit 2, Appendix Exhibits 3 and 4).27 In rural counties, a lower proportion of care was via telemedicine than in urban counties (23.9% rural vs. 30.7% urban counties, p<0.001). After adjustment, differences in telemedicine use within each patient characteristic were statistically significant (all p<0.001, Appendix Exhibits 3 and 4).27

EXHIBIT 2.

Percent of Weekly Total Visits Delivered by Telemedicine and Adjusted Mean Number of Weekly Total Visits per 1,000 Members in the Pre- to COVID-19 periods by Demographic Characteristic

Authors’ analysis of data from OptumLabs Data Warehouse, January 1, 2020 – June 16, 2020.

We measured quartiles of county-level median household income (INCOME) and percent of white individuals (% WHITE) using 2010 US Census data. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and average marginal effects (AMEs) for each demographic characteristic in the pre- and COVID-19 period were statistically significant at a p-value of 0.001 (Appendix Exhibits 2 and 3). Left panel presents the percent of total visits delivered by telemedicine in the pre- and COVID-19 period (measured by column 3 divided by column 6 for pre-COVID period and column 9 divided by column 12 for COVID-19 period in Appendix Exhibit 3). Right panel presents the AMEs for total visits for the pre- and COVID-19 period (columns 6 and 12 in Appendix Exhibit 3 for pre- and COVID-19 period, respectively)

In-Person and Telemedicine Visits by Clinical Specialty

In the pre-COVID period, at the provider-level, fewer than 2% of clinicians in each specialty delivered any outpatient care via telemedicine, with the exception of mental health clinicians (e.g. psychologists: 4.4%, psychiatrists: 5.5%, and social workers: 4.2%) (Appendix Exhibit 5).27 In the COVID-19 period, telemedicine was used at least once by over half of the clinicians in several specialties: endocrinologists (67.7% endocrinologists), gastroenterologists (57.0%), neurologists (56.3%), pain management physicians (50.6%), psychiatrists (50.2%), and cardiologists (50.0%). Specialties with the least telemedicine engagement included optometrists (3.3% providing at least one telemedicine visit during the pandemic), physical therapists (6.6%), ophthalmologists (9.3%) and orthopedic surgeons (20.7%).

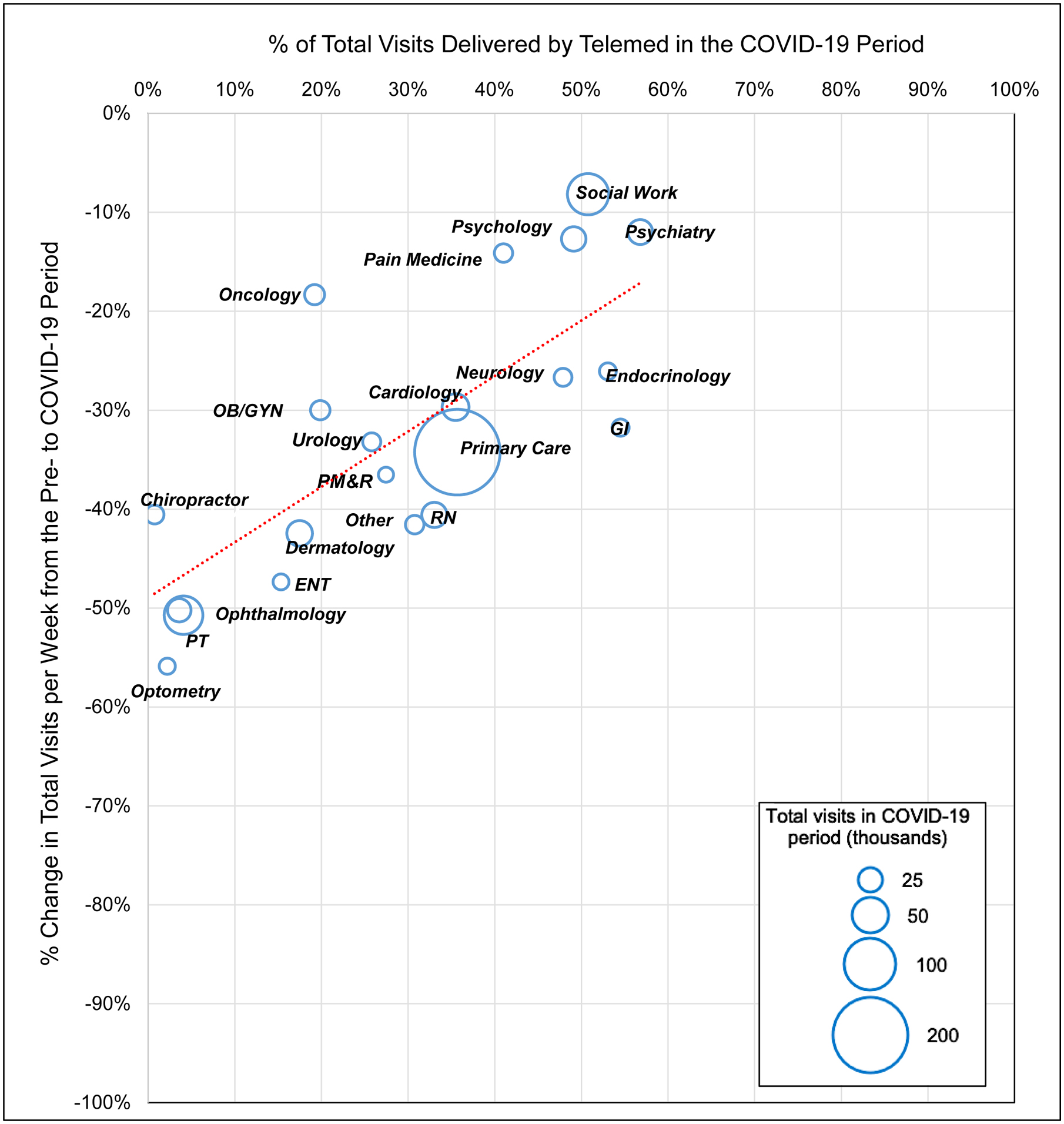

At the visit-level, clinical specialties that provided a larger percentage of total visits via telemedicine in the COVID-19 period had a smaller decrease in total visits per week from the pre- to COVID-19 periods (r=0.77 for correlation between the two measures; Exhibit 3, Appendix Exhibit 6).27 Among five specialties, close to half or more of total visits were provided via telemedicine in the COVID-19 period: psychiatry (56.8% of totals visits during COVID-19), gastroenterology (54.5%), endocrinology (53.1%), social work (50.8%), psychology (49.1%), and neurology (47.9%).

EXHIBIT 3.

Correlation of Change in Weekly Total Visits from the Pre- to COVID-19 periods and Weekly Total Visits Delivered by Telemedicine in the COVID-19 period, by Clinician Specialty

Authors’ analysis of data from OptumLabs Data Warehouse

Circle size indicates the proportion of total visits in the COVID-19 period by clinician specialty (see Appendix Exhibit 1 for full list)27. r=0.77 for correlation between the two measures. Abbreviations: physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R); obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN); otolaryngology (ENT); physical therapy (PT); gastroenterology (GI); registered nurse (RN)

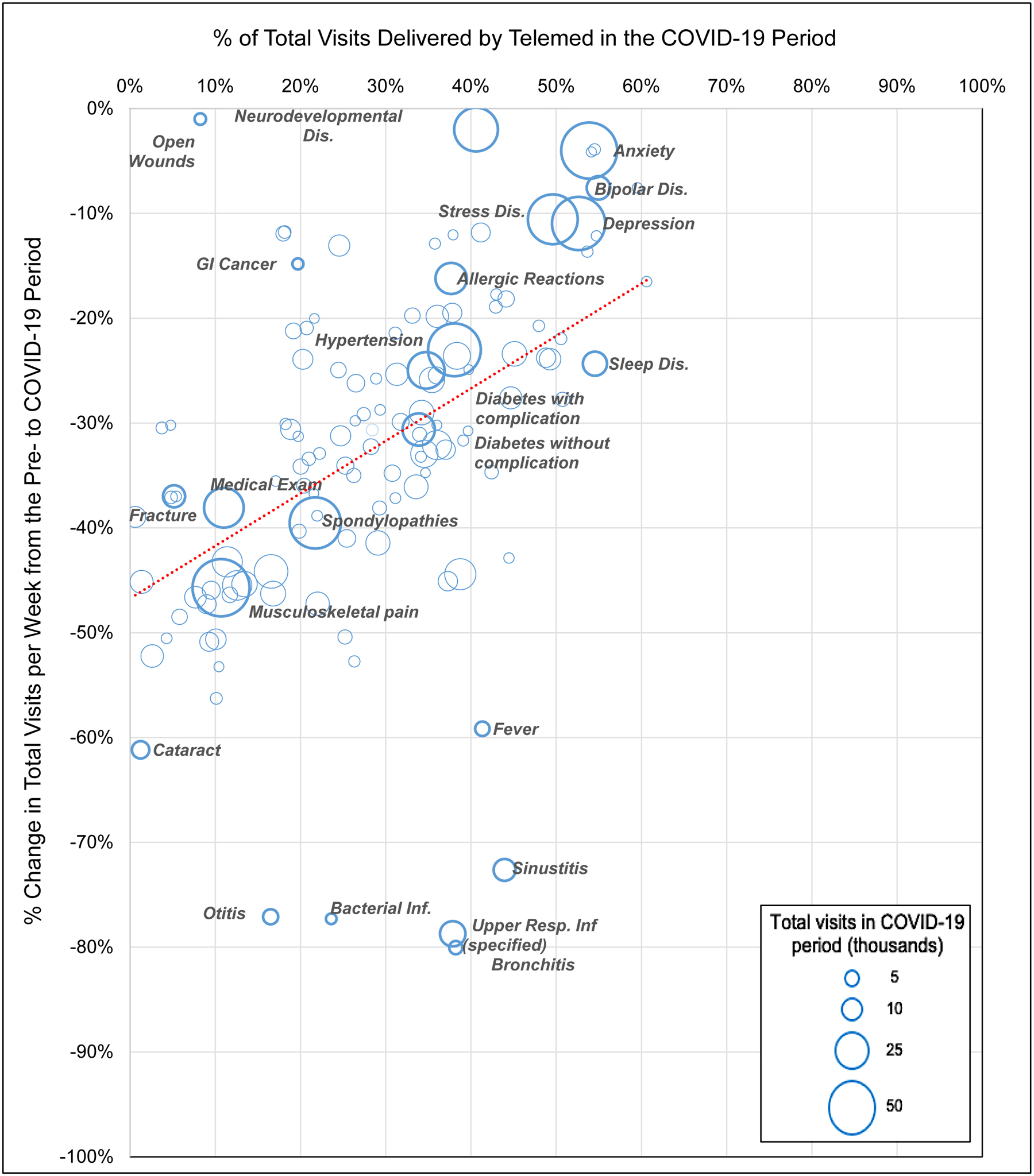

In-Person and Telemedicine Visits by Condition

On average, conditions for which a larger percentage of total visits were conducted via telemedicine in the COVID-19 period had a smaller decrease in total visits per week from the pre to COVID-19 periods (r=0.46 for correlation between the two measures; Exhibit 4, Appendix Exhibit 7).27 Conditions with the highest proportion of visits provided via telemedicine in the COVID-19 period included mental illnesses such as depression (52.6%), bipolar disorder (55.0%), and anxiety (53.9%). For these conditions, total visits per week decreased less than 11% from the pre- to COVID-19 periods. In contrast, common chronic conditions like hypertension (38.1% of visits delivered via telemedicine) and diabetes without complication (33.9%) showed a somewhat different pattern, with lower use of telemedicine and a substantial decrease in total visit volume (−23.0% and −30.6% change in total visits, respectively), though many other conditions had larger drops in total volume.

EXHIBIT 4.

Correlation of Change in Weekly Total Visits from the Pre- to COVID-19 periods and Weekly Total Visits Delivered by Telemedicine in the COVID-19 period by Diagnosis Category

Authors’ analysis of data from OptumLabs Data Warehouse

Circle size indicates the proportion of total visits in the COVID-19 period by clinician specialty (see Appendix Exhibit 1 for full list)27. r=0.46 for correlation between the two measures. Abbreviations: Infections (Inf); Disorder (Dis)

In contrast, there were some clinical conditions with a large decline in total visits and substantial telemedicine use. These include common acute respiratory conditions such as upper respiratory infection (−78.7% change in total visits, 37.9% of visits delivered via telemedicine), bronchitis (−80.0% change in total visits, 38.2% telemedicine), and sinusitis (−72.6% change in total visits, 43.9% telemedicine) fell substantially (Exhibit 4, Appendix Exhibit 7).27 In contrast, eye conditions such as cataracts (−61.2% change in total visits, 1.2% telemedicine) and glaucoma (−52.2.% change in total visits, 2.6% telemedicine) saw a substantial decline in visits and little telemedicine use.

DISCUSSION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, growth in telemedicine use varied substantially across patient demographics, clinical specialties, and medical conditions. We observed higher telemedicine use among those living in lower-income and higher minority resident counties. Telemedicine use also varied dramatically across different specialties. Specialties such as psychiatry, endocrinology, and neurology had the greatest uptake of telemedicine and the smallest decline in total visits, compared to specialties like ophthalmology, which had little telemedicine use and lost most of its clinical volume early in the pandemic.

Our findings illustrate the far-reaching scope of deferred care during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. While there was variability in the magnitude of changes across different patient populations and clinical disciplines, every segment of the health care system experienced a drop in the overall volume of care, including important common chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. Lost volume from chronic condition management could lead to worse downstream outcomes if more patients experience poor control of their disease, as seen with care disruptions in past natural disasters.20,21 On the other hand, large drops in visit volume for common, low-risk respiratory conditions like sinusitis or bronchitis could represent a drop in discretionary care without lasting health impact. The unusually large drop in visit volume in respiratory infections could also reflect lower transmission of non-COVID-19 respiratory viruses from widespread social distancing measures.

The health care system may struggle to catch up with the large amount of deferred care. Clinicians are likely to limit clinical volume due to COVID-19 precautions and patients may continue to avoid the health system due to fear of the virus. Prior evidence looking at within-office transmission of influenza-like illness suggests that patients can transmit respiratory infections to other patients present in the office at the same time.35,36 The magnitude of this problem will likely vary across specialties. Telemedicine adoption was uneven across specialties and conditions in ways that likely reflected varying need for physical exam or testing. For example, ophthalmology clinics may have particularly pronounced challenges catching up with delayed routine care for retinal disease or glaucoma using telemedicine as diagnostic examinations require specialized equipment. “Cognitive” specialties such as psychiatry, endocrinology, and neurology that rely less exclusively on the physical exam had the greatest uptake of telemedicine and the smallest declines in overall visits. Common chronic conditions like hypertension and diabetes fell between these two extremes, with a large drop in overall care somewhat mitigated by a substantial increase in the provision of telemedicine.

Our analyses, replicated at the health system level, could inform policy to make up for months of deferred care. Health systems could allocate resources to patient outreach efforts such as phone calls or reminder emails, prioritizing patients whose conditions saw the largest drop in visit volume. Furthermore, additional clinical capacity could be allocated to specialties with the largest backlogs of deferred care. Finally, health systems could prioritize chronic illness populations, who were more likely to have deferred care, for targeted population management.

Despite concerns of the “digital divide” in telemedicine access,14,37 we found higher telemedicine use in low-income and minority counties during COVID-19, while changes in total visits were similar. It is important to interpret these findings in the context of our study population, which disproportionately included employed adults and their family members with commercial insurance. Therefore, these results imply that, conditional on having commercial insurance or a Medicare Advantage plan, enrollees living in lower income or higher minority counties had similar or greater use of telemedicine. An alternate interpretation of these findings is that enrollees in more disadvantaged counties have lower access to in-person care during the pandemic given their higher use of telemedicine and similar rates of overall visits in the COVID-19 period. This could reflect higher burden of COVID-19 in those communities and greater reluctance of providers to offer in-person visits. Consistent with the “digital divide” concern, we did observe that telemedicine use and overall outpatient access during COVID-19 was lower in rural areas than urban areas. One potential explanation for this finding is that limited broadband availability in rural areas is a barrier to telemedicine use.17

CONCLUSION

Telemedicine use during COVID-19 varied across different clinical settings and patient populations, without a pattern of systematic exclusion of enrollees in disadvantaged areas. Future research is needed to understand the persistence of these trends over longer time periods and the impact of these changes on patients’ health.

Supplementary Material

NOTES

- 1.Jeffery MM, D’Onofrio G, Paek H, et al. Trends in emergency department visits and hospital admissions in health care systems in 5 states in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. Published August 03, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kansagra AP, Goyal MS, Hamilton S, Albers GW. Collateral effect of Covid-19 on stroke evaluation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):400–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2014816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaduganathan M, van Meijgaard J, Mehra MR, Joseph J, O’Donnell CJ, Warraich HJ. Prescription fill patterns for commonly used drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2524–2526. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baum A, Schwartz MD. Admissions to Veterans Affairs hospitals for emergency conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(1):96–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient visits: practices are adapting to the new normal. Commonwealth Fund. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. doi: 10.26099/2v5t-9y63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett ML, Ray KN, Souza J, Mehrotra A. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005–2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147–2149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma S Early impact of CMS expansion of Medicare telehealth during COVID-19. Health Aff Blog. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed July 16, 2020. doi: 10.1377/hblog20200715.454789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154–161. doi: 10.1056/nejmra1601705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. Newsroom. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epic Health Research Network. Expansion of telehealth during COVID-19 pandemic. Published May 5, 2020. https://ehrn.org/expansion-of-telehealth-during-covid-19-pandemic/.

- 11.America’s Health Insurance Plans. Health insurance providers respond to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Published July 24, 2020. https://www.ahip.org/health-insurance-providers-respond-to-coronavirus-covid-19/.

- 12.Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrotra A, Ray K, Brockmeyer DM, Barnett ML, Bender JA. Rapidly converting to “virtual practices”: outpatient care in the era of Covid-19. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. Published April 1, 2020. doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velasquez D, Mehrotra A. Ensuring the growth of telehealth during COVID-19 does not exacerbate disparities in care. Health Aff Blog. Published May 8, 2020. doi: 10.1377/hblog20200505.591306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of disparities in digital access among Medicare beneficiaries and implications for telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. Published August 03, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam K, Lu AD, Shi Y, Covinsky KE. Assessing telemedicine unreadiness among older adults in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. Published August 03, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilcock AD, Rose S, Busch AB, et al. Association between broadband internet availability and telemedicine use. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1580–1582. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bridging the digital divide for all Americans. fcc.gov. https://www.fcc.gov/about-fcc/fcc-initiatives/bridging-digital-divide-all-americans. Accessed October 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox B, Sizemore OJ. Telehealth: fad or the future. Epic Health Research Network. Published August 18, 2020. https://www.ehrn.org/telehealth-fad-or-the-future/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baum A, Barnett ML, Wisnivesky J, Schwartz MD. Association between a temporary reduction in access to health care and long-term changes in hypertension control among veterans after a natural disaster. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915111–e1915111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A, et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.OptumLabs. OptumLabs and OptumLabs Data Warehouse (OLDW) Descriptions and Citation. Eden Prairie, MN: n.p., May 2019. PDF. Reproduced with permission from OptumLabs. [Google Scholar]

- 23.UnitedHealthcare. COVID-19 telehealth. Updated July 24, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.uhcprovider.com/en/resource-library/news/Novel-Coronavirus-COVID-19/covid19-telehealth-services/covid19-telehealth-services-telehealth.html.

- 24.NYTimes. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Data in the United States. Updated November 2, 2020. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. Newsroom. Published March 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-trump-expands-telehealth-benefits-medicare-beneficiaries-during-covid-19-outbreak. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of telehealth services. Updated April 30, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes.

- 27.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 28.UnitedHealthcare. Coverage summary: telemedicine/telehealth services. Published 2017. Accessed Aug 29, 2017. https://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/Tools%20and%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/UnitedHealthcare%20Medicare%20Coverage/Telehealth_and_Telemedicine_UHCMA_CS.pdf.

- 29.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Telehealth services. Published 2016. Accessed Aug 29, 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/TelehealthSrvcsfctsht.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR). Updated May 28, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/ccs_refined.jsp.

- 31.WWAMI RUCA Rural Health Research Center. Accessed July 15, 2020. http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-maps.php.

- 32.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software, Version 3.7 Updated June 22, 2017. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp.

- 33.Tseng P, Kaplan RS, Richman BD, Shah MA, Schulman KA. Administrative costs associated with physician billing and insurance-related activities at an academic health care system. JAMA. 2018;319(7):691–697. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson J, Bock A. The benefit of using both claims data and electronic medical record data in health care analysis. Optum. Published 2012. https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/whitePapers/Benefits-of-using-both-claims-and-EMR-data-in-HC-analysis-WhitePaper-ACS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feemster K, Localio R, Grundmeier R, Metlay JP, Coffin SE. Incidence of healthcare-associated influenza-like illness after a primary care encounter among young children. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2019(8):191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmering JE, Polgreen LA, Cavanaugh JE, Polgreen PM. Are well-child visits a risk factor for subsequent influenza-like illness visits? Infection control and hospital epidemiology 2014(35):251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horn D Telemedicine is booming during the pandemic. But it’s leaving people behind Washington Post. Published July 9, 2020. Accessed July 31, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/07/09/telemedicine-is-booming-during-pandemic-its-leaving-people-behind/. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.