Abstract

The nucleoprotein (N) from SARS-CoV-2 is an essential cofactor of the viral replication transcription complex and as such represents an important target for viral inhibition. It has also been shown to colocalize to the transcriptase-replicase complex, where many copies of N decorate the viral genome, thereby protecting it from the host immune system. N has also been shown to phase separate upon interaction with viral RNA. N is a 419 amino acid multidomain protein, comprising two folded, RNA-binding and dimerization domains spanning residues 45–175 and 264–365 respectively. The remaining 164 amino acids are predicted to be intrinsically disordered, but there is currently no atomic resolution information describing their behaviour. Here we assign the backbone resonances of the first two intrinsically disordered domains (N1, spanning residues 1–44 and N3, spanning residues 176–263). Our assignment provides the basis for the identification of inhibitors and functional and interaction studies of this essential protein.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Nucleoprotein, Intrinsically disordered protein, NMR, COVID-19, Dynamics, Relaxation

Biological context

The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) represents a serious threat to the stability of human societies throughout the world. In order to eradicate the disease, it is necessary to foster research aimed at the development of vaccines or effective antiviral inhibitors. The establishment of effective therapeutic strategies requires the identification of molecular targets against which inhibitory strategies can be developed.

The nucleoprotein (N) of SARS-CoV-2 is a crucial component of the replication machinery, localizing to the viral replicase–transcriptase complex (4, 5, 7–9). Beta-coronaviral N encapsidates the viral genome within a nucleocapsid, formed from multiple copies of the protein (Zúñiga et al. 2007; McBride et al. 2014), thereby providing protection from the host immune system, and is essential for regulation of viral gene transcription (Wu et al. 2014). N is also produced in abundance in infected cells and is an important marker for infection. In order to identify possible avenues targeting the essential roles of N in the viral cycle, it is important to understand the structure and function of this complex protein at atomic resolution.

N is a 419 amino acid multi-domain protein, comprising folded, RNA-binding (N2) and dimerization (N4) domains spanning residues 45–175 and 266–365 respectively (Chang et al. 2014). N2 has been described using both X-ray crystallography (Kang et al. 2020; Peng et al. 2020) and NMR spectroscopy (Dinesh et al. 2020). The dimerization domain N4 has been described using X-ray crystallography (Ye et al. 2020; Peng et al. 2020) and N has been shown to form higher order oligomers via N4 (Ye et al. 2020; Zeng et al. 2020; Lutomski et al. 2020). The remaining 164 amino acids comprising N1, N3 and N5 are predicted to be intrinsically disordered, but despite evidence that these domains are essential for function in the related Mouse Hepatitis virus (Keane and Giedroc 2013), there is currently no atomic resolution information describing their behaviour in solution. Nuclear magnetic resonance is the ideal tool for studying the conformational behaviour of highly dynamic or intrinsically disordered proteins (Jensen et al. 2014).

Here we present the assignment of the backbone resonances of the first two intrinsically disordered domains (N1, spanning residues 1–44 and N3, the central disordered domain, spanning residues 176–265). The N3 IDR (175–263) comprises a serine-arginine (SR) rich domain that is phosphorylated in virions, a modification that plays a role in both function and localization of SARS-CoV-1 N (Peng et al. 2008). N5 is thought to contribute to the oligomerization of N in SARS-CoV-1 (Lo et al. 2013).

Recent studies used single molecule FRET and molecular modelling (Cubuk et al. 2020) to describe the global conformational behaviour of N1 and N3. Peptides representing the SR region of N3 in its phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms were also described using NMR spectroscopy (Savastano et al. 2020). Mass spectrometry has also revealed a number of auto-catalytic sites in N, two of which are present in N3 (Lu et al. 2020; Lutomski et al. 2020).

N from SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to undergo liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) upon mixing with RNA (Cubuk et al. 2020; Savastano et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2020; Iserman et al. 2020; Perdikari et al. 2020; Carlson et al. 2020; Lu et al. 2020; Jack et al. 2020). The formation of membraneless condensates by colocalization of components involved in viral replication in liquid droplets is prevalent in negative sense single strand RNA viruses, such as rabies (Nikolic et al. 2017), measles (Zhou et al. 2019; Guseva et al. 2020), and Nipah (Ringel et al. 2019). It is not yet known which interactions are responsible for LLPS in SARS-CoV-2, but it is highly likely that the intrinsically disordered domains are involved in this process. Moreover, N2 and N3 were shown to be essential for phase separation with RNA (Lu et al. 2020).

Here, we present backbone resonance assignment and NMR relaxation of two domains (N1 and N3) of N, providing data prerequisite for characterisation of the functional modes of this enigmatic protein, screening of interaction partners and detailed mapping of interactions.

Methods and experiments

Sample preparation

The primary sequence of N from SARS-CoV-2 was extracted from NCBI genome entry NC_045512.2 [GenBank entry MN908947.3 (Wu et al. 2014)]. Commercially synthesized genes (Genscript Biotech) were codon-optimized for expression in Escherichia coli and subcloned in a pET21b(+) vector. Hexa-histidine and TEV-cleavage tags were included at the N-terminus to facilitate protein purification. After protease cleavage, the proteins contain N-terminal GRR- extensions. For 15N and 13C isotope labelling, cells were grown in M9-minimal medium supplemented with 15N–NH4–Cl and 13C6–d–glucose (1 and 2 g/L respectively).

Both nucleoprotein constructs (N123, comprising residues 1–263 and N3, comprising residues 175–263) were cloned into a pESPRIT vector between the AatII and NotI cleavage sites with His8-tag and TEV cleavage sites at the N-terminus (GenScript Biotech Netherlands). Transformation was performed by heat-shock and proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) for 5 h at 37°C after induction at an optical density of 0.6 with 1 mM isopropyl–b–d–thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were harvested by centrifugating at 5000 rpm, resuspended in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 500 mM NaCl buffer, lysed by sonication, and centrifugated again at 18,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was subjected to standard Ni purification. Proteins were eluted with 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 500 mM NaCl and 500 mM imidazole. Samples were then dialysed against 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT at room temperature overnight. Following TEV cleavage, samples were concentrated and subjected to size exclusion chromatography (SEC, Superdex 75/200) in 50 mM Na-Phosphate (pH 6.5), 250 mM NaCl 2 mM DTT buffer (NMR buffer). Proteins were studied at 600 and 150 μM for N3 and 0.91 mM for N123.

NMR experiments

BEST and BEST-TROSY (BT) double and triple resonance assignment experiments, including BEST-HNCA, BEST HN(CO)CA, BT-HNCO (Lescop et al. 2007; Solyom et al. 2013), were recorded on 15N,13C-labeled samples at 298 K using Bruker Avance III spectrometers equipped with a cryoprobe at 1H frequencies of 600 and 850 MHz. R1rho relaxation experiments (Lakomek et al. 2012) were recorded at 150 μM protein concentration and 298 K in a 50 mM Na-Phosphate (pH 6.5), 250 mM NaCl 2 mM DTT buffer at 950 MHz.

Residues 217–224 and 231–235 of N3 were assigned using a deuterated 13C 15N labelled sample at 300 µM. BEST-HNCA, BEST-HN(CO)CA with one increment in 15N dimension were recorded at 850 MHz, allowing detection of weak additional peaks of the helical region and connection with those already assigned. All spectra were processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed using CCPNMR Analysis Assign (Skinner et al. 2016) and NMRFAM-SPARKY (Lee et al. 2015). Assignment was further assisted by comparison to BMRB entry 34511 (Dinesh et al. 2020) of the N-terminal RNA-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein, specifically nucleoprotein residues 44 to 180 (N2).

Assignments and data deposition

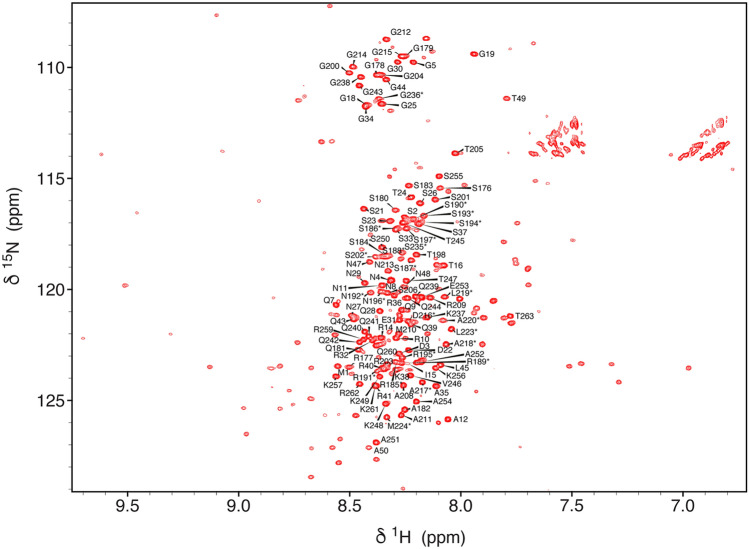

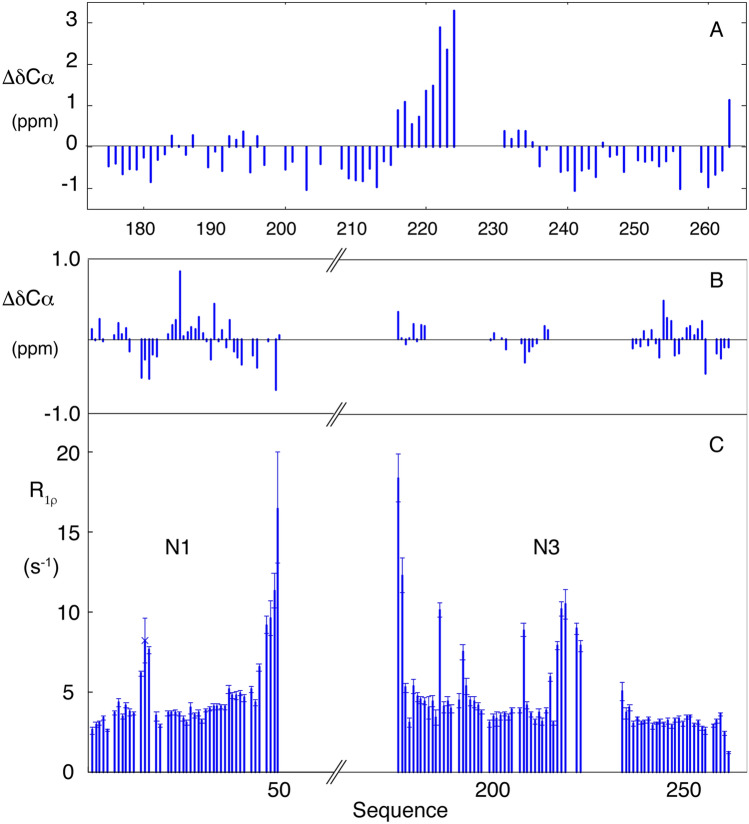

The HSQC of N3 is typical of an intrinsically disordered protein (Fig. 1). Most peaks in N3 are reproduced in the spectrum of N123, that also reveals the presence of the folded RNA-binding domain N2, in addition to disordered peaks from N1 (intensity of peaks from the first 15 residues of N3 were reduced in N123, probably due to the proximity with N2). The assignment of N2 has been published (Dinesh et al. 2020), and assignment of N1 in N123 (Fig. 2) and N3 in its isolated form and in the context of N123 were accomplished using standard triple resonance approaches. A high percentage of resonances could be assigned in N3 (84% 1HN, 84% 15NH, 82% 13Cα and 76% 13C) and N1 in the context of N123 (94% 1HN, 94% 15NH, 100% 13Cα, 57% 13Cβ and 100% 13C). These assignments have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Databank (BMRB ID: 50557, comprising backbone resonance assignment of N3 and 50558, comprising backbone resonance assignment of N1 and of resolved resonances in N3, both in the context of N123).

Fig. 1.

1H–15N HSQC of N3 (175–263) from SARS-CoV-2. The spectrum was acquired on an 850 MHz spectrometer at 298 K at a concentration of 150 μM in 50 mM Na-phosphate, pH 6.0, 250 mM NaCl. Assigned backbone 1H–15N peaks are labelled

Fig. 2.

1H–15N BEST-TROSY of N123 (1–263) from SARS-CoV-2. The spectrum was acquired on a 950 MHz spectrometer at 298 K at a concentration of 150 μM in 50 mM Na-phosphate, pH 6.5, 250 mM NaCl. Backbone 1H–15N peaks assigned in this study are labelled, resonances transferred from assignment of N3 (Fig. 1) are starred. The disperse signals from N2 for which an assignment is already available (Dinesh et al. 2020) are present but have not been labelled

Secondary structural propensity and dynamics

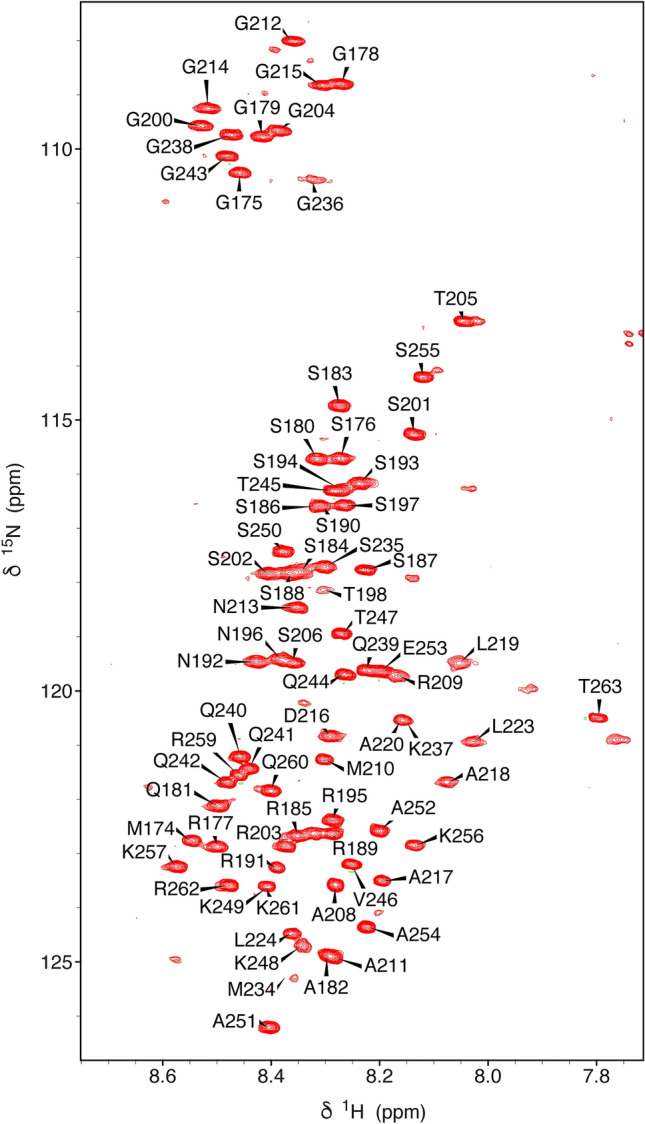

Resonance assignment of the two domains confirms the disordered nature of N1 and N3 (Figs. 1 and 2). The linker region (N3) connecting the two folded domains (N2 and N4), comprises intrinsically disordered SR-rich and polar termini, flanking a central hydrophobic strand that exhibits a pronounced helical propensity (> 30% from 216 to 224 with near 100% helical population from position 220) (Fig. 3). Assignment of 5 residues at the centre of this region was not possible, possibly due to dimerization mediated by the helix. This region is also predicted to form a hydrophobic helix in SARS-CoV (Chang et al. 2009). Recent simulations (Cubuk et al. 2020) also proposed the presence of a weakly (< 20%) helical motif in the SR region at the N-terminal region of N (176–185), which is not seen experimentally, although there is overlap of predicted helical propensity (< 30% helix predicted to stretch from 213 to 225) in the vicinity of experimentally observed helical propensity. Studies of isolated peptides (Savastano et al. 2020) also suggested a helical propensity in the SR region which is not seen here.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of chemical shifts and relaxation rates for N1 and N3 from SARS-CoV-2. a Secondary Cα chemical shifts for the disordered residues in N3. b Secondary Cα chemical shifts for the disordered residues in N123 that are observed in triple resonance assignment experiments. c Rotating frame relaxation rates measured in N123. Measurements were made at 950 MHz at 298 K using sample concentration of 150 μM. Residues from N2 are not shown

Assignment of the backbone resonances of the N-terminal domain of N (N1) within the N123 construct (Fig. 2) reveals the presence of an intrinsically disordered chain with no detectable secondary structural propensity and only very slight differences around residue 248 compared to free N3. Note that a number of resonances that were visible in N3 were not assigned in N123, most probably due to short relaxation times experienced in the vicinity of the helical motif that limits transfer of magnetization in triple resonance experiments. Nevertheless putative transfer of assignment was proposed on the basis of the 15N–1H correlation spectra of N3 and N123 (starred resonances in Fig. 2). Spin relaxation measured in N123 confirms the highly dynamic nature of N1 and N3 in the context of the folded RNA binding domain N2 (Fig. 3), with relaxation rates in the expected range for a disordered domain (Adamski et al. 2019), with the exception of the helical element in N3 and three consecutive residues in N1 (R14-I15-T16) that both show elevated rates.

In conclusion, NMR backbone assignment and preliminary relaxation studies provide the basis for further NMR studies of this important drug target, providing the tools necessary for the identification of inhibitors and for detailed functional studies of this essential protein.

Acknowledgements

This work used the platforms of the Grenoble Instruct-ERIC center (ISBG; UMS 3518 CNRS-CEA-UGA-EMBL) within the Grenoble Partnership for Structural Biology (PSB), supported by FRISBI (ANR-10-INBS-05-02) and GRAL, financed within the University Grenoble Alpes graduate school (Ecoles Universitaires de Recherche) CBH-EUR-GS (ANR-17-EURE-0003). IBS acknowledges integration into the Interdisciplinary Research Institute of Grenoble (IRIG CEA). IBS acknowledges integration into the Interdisciplinary Research Institute of Grenoble (IRIG CEA). The authors acknowledge discussions and encouragement from the COVID-19 NMR consortium under the coordination of Prof. Harald Schwalbe and colleagues. Financial support from the TGIR-RMN-THC Fr3050 CNRS for conducting the research is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Serafima Guseva and Laura Mariño Perez have contributed equally to this work.

References

- Adamski W, Salvi N, Maurin D, et al. A unified description of intrinsically disordered protein dynamics under physiological conditions using NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:17817–17829. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CR, Asfaha JB, Ghent CM, et al. Phosphorylation modulates liquid-liquid phase separation of the SARS-CoV-2 N protein. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.28.176248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-K, Hsu Y-L, Chang Y-H, et al. Multiple nucleic acid binding sites and intrinsic disorder of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein: implications for ribonucleocapsid protein packaging. J Virol. 2009;83:2255–2264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02001-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Hou M-H, Chang C-F, et al. The SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein—forms and functions. Antivir Res. 2014;103:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cui Y, Han X, et al. Liquid–liquid phase separation by SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and RNA. Cell Res. 2020;30:1143–1145. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00408-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubuk J, Alston JJ, Incicco JJ, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein is dynamic, disordered, and phase separates with RNA. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.17.158121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio FD, Grzesiek S, Vuister G, et al. NMRPIPE–A multidimensional spectral processing system based on unix pipes. J biomol nmr. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh DC, Chalupska D, Silhan J, et al. Structural basis of RNA recognition by the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.02.022194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guseva S, Milles S, Jensen MR, et al. Measles virus nucleo- and phosphoproteins form liquid-like phase-separated compartments that promote nucleocapsid assembly. Sci Adv. 2020 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iserman C, Roden C, Boerneke M, et al. Specific viral RNA drives the SARS CoV-2 nucleocapsid to phase separate. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.11.147199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jack A, Ferro LS, Trnka MJ, et al. SARS CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein forms condensates with viral genomic RNA. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.09.14.295824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MR, Zweckstetter M, Huang J, Blackledge M. Exploring free-energy landscapes of intrinsically disordered proteins at atomic resolution using NMR spectroscopy. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6632–6660. doi: 10.1021/cr400688u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Yang M, Hong Z, et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein RNA binding domain reveals potential unique drug targeting sites. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane SC, Giedroc DP (2013) Solution structure of mouse Hepatitis Virus (MHV) nsp3a and determinants of the interaction with MHV nucleocapsid (N) protein. J Virol 87:3502–3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lakomek N-A, Ying J, Bax A. Measurement of 15N relaxation rates in perdeuterated proteins by TROSY-based methods. J Biomol NMR. 2012;53:209–221. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9626-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Tonelli M, Markley JL. NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1325–1327. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescop E, Schanda P, Brutscher B. A set of BEST triple-resonance experiments for time-optimized protein resonance assignment. J Magn Reson. 2007;187:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y-S, Lin S-Y, Wang S-M, et al. Oligomerization of the carboxyl terminal domain of the human coronavirus 229E nucleocapsid protein. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Ye Q, Singh D, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein forms mutually exclusive condensates with RNA and the membrane-associated M protein. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.30.228023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutomski CA, El-Baba TJ, Bolla JR, Robinson CV. Autoproteolytic products of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein are primed for antibody evasion and virus proliferation. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.06.328112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBride R, van Zyl M, Fielding BC. The coronavirus nucleocapsid is a multifunctional protein. Viruses. 2014;6:2991–3018. doi: 10.3390/v6082991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolic J, Le Bars R, Lama Z, et al. Negri bodies are viral factories with properties of liquid organelles. Nat Commun. 2017;8:58. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng T-Y, Lee K-R, Tarn W-Y. Phosphorylation of the arginine/serine dipeptide-rich motif of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein modulates its multimerization, translation inhibitory activity and cellular localization. FEBS J. 2008;275:4152–4163. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Du N, Lei Y, et al. Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and their perspectives for drug design. EMBO J. 2020;39(20):e105938. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020105938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdikari TM, Murthy AC, Ryan VH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation stimulated by RNA and partitions into phases of human ribonucleoproteins. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.09.141101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ringel M, Heiner A, Behner L, et al. Nipah virus induces two inclusion body populations: Identification of novel inclusions at the plasma membrane. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007733. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savastano A, de Opakua AI, Rankovic M, Zweckstetter M. Nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 phase separates into RNA-rich polymerase-containing condensates. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.18.160648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner SP, Fogh RH, Boucher W, et al. CcpNmr analysis assign: a flexible platform for integrated NMR analysis. J Biomol NMR. 2016;66:111–124. doi: 10.1007/s10858-016-0060-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solyom Z, Schwarten M, Geist L, et al. BEST-TROSY experiments for time-efficient sequential resonance assignment of large disordered proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2013;55:311–321. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-H, Chen P-J, Yeh S-H. Nucleocapsid phosphorylation and RNA helicase DDX1 recruitment enables coronavirus transition from discontinuous to continuous transcription. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q, West AMV, Silletti S, Corbett KD. Architecture and self-assembly of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Bio Rxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.17.100685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, Liu G, Ma H, et al. Biochemical characterization of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;527:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.04.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Su JM, Samuel CE, Ma D. Measles virus forms inclusion bodies with properties of liquid organelles. J Virol. 2019 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00948-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga S, Sola I, Moreno JL, et al. Coronavirus nucleocapsid protein is an RNA chaperone. Virology. 2007;357:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]