Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Can asoprisnil, a selective progesterone receptor modulator, provide clinically meaningful improvements in heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) associated with uterine fibroids with an acceptable safety profile?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Uninterrupted treatment with asoprisnil for 12 months effectively controlled HMB and reduced fibroid and uterine volume with few adverse events.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

In a 3-month study, asoprisnil (5, 10 and 25 mg) suppressed uterine bleeding, reduced fibroid and uterine volume, and improved hematological parameters in a dose-dependent manner.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

In two Phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicentre studies, women received oral asoprisnil 10 mg, asoprisnil 25 mg or placebo (2:2:1) once daily for up to 12 months.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Premenopausal women ≥18 years of age in North America with HMB associated with uterine fibroids were included (N = 907). The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of women who met all three predefined criteria at 12 months or the final month for patients who prematurely discontinued: (1) ≥50% reduction in monthly blood loss (MBL) by menstrual pictogram, (2) hemoglobin concentration ≥11 g/dL or an increase of ≥1 g/dL, and (3) no interventional therapy for uterine fibroids. Secondary efficacy endpoints included changes in other menstrual bleeding parameters, volume of the largest fibroids, uterine volume and health-related quality of life (HRQL).

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

In all, 90% and 93% of women in the asoprisnil 10-mg and 25-mg groups, respectively, and 35% of women in the placebo group met the primary endpoint (P < 0.001). Similar results were observed at month 6 (P < 0.001). The percentage of women who achieved amenorrhea in any specified month ranged from 66–78% in the asoprisnil 10-mg group and 83–93% in the asoprisnil 25-mg group, significantly higher than with placebo (3–12%, P < 0.001). Hemoglobin increased rapidly (by month 2) with asoprisnil treatment and was significantly higher versus placebo throughout treatment. The primary fibroid and uterine volumes were significantly reduced from baseline through month 12 with asoprisnil 10 mg (median changes up to −48% and −28%, respectively) and 25 mg (median changes up to −63% and −39%, respectively) versus placebo (median changes up to +16% and +13%, respectively; all P < 0.001). Dose-dependent, significant improvements in HRQL (Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life instrument) were observed with asoprisnil treatment. Asoprisnil was generally well tolerated. Endometrial biopsies indicated dose- and time-dependent decreases in proliferative patterns and increases in quiescent or minimally stimulated endometrium at month 12 of treatment. Although not statistically significantly different at month 6, mean endometrial thickness at month 12 increased by ~2 mm in both asoprisnil groups compared with placebo (P < 0.01). This effect was associated with cystic changes in the endometrium on MRI and ultrasonography, which led to invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in some asoprisnil-treated women.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

Most study participants were black; few Asian and Hispanic women participated. The study duration may have been insufficient to fully characterize the endometrial effects.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Daily uninterrupted treatment with asoprisnil was highly effective in controlling menstrual bleeding, improving anemia, reducing fibroid and uterine volume, and increasing HRQL in women with HMB associated with uterine fibroids. However, this treatment led to an increase in endometrial thickness and invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, with potential unknown consequences.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This trial was funded by AbbVie Inc. (prior sponsors: TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc., Abbott Laboratories). E.A. Stewart was a site investigator in the Phase 2 study of asoprisnil and consulted for TAP during the design and conduct of these studies while at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She received support from National Institutes of Health grants HD063312, HS023418 and HD074711 and research funding, paid to Mayo Clinic for patient care costs related to an NIH-funded trial from InSightec Ltd. She consulted for AbbVie, Allergan, Bayer HealthCare AG, Gynesonics, and Welltwigs. She received royalties from UpToDate and the Med Learning Group. M.P. Diamond received research funding for the conduct of the studies paid to the institution and consulted for AbbVie. He is a stockholder and board and director member of Advanced Reproductive Care. He has also received funding for study conduct paid to the institution from Bayer and ObsEva. A.R.W. Williams consulted for TAP and Repros Therapeutics Inc. He has current consultancies with PregLem SA, Gedeon Richter, HRA Pharma and Bayer. B.R. Carr consulted for and received research funding from AbbVie. E.R. Myers consulted for AbbVie, Allergan and Bayer. R.A. Feldman received compensation for serving as a principal investigator and participating in the conduct of the trial. W. Elger was co-inventor of several patents related to asoprisnil. C. Mattia-Goldberg is a former employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock or stock options. B.M. Schwefel and K. Chwalisz are employees of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock or stock options.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

TRIAL REGISTRATION DATE

7 September 2005; 8 September 2005.

DATE OF FIRST PATIENT’S ENROLMENT

12 September 2002; 6 September 2002.

Keywords: asoprisnil, uterine leiomyomata, uterine leiomyoma, uterine fibroid, heavy menstrual bleeding, fibroids, J867, selective progesterone receptor modulator

Introduction

Uterine fibroids (leiomyomata) are the most common neoplasms in premenopausal women. The cumulative incidence is ~80% and 70%, respectively, in black and white women, (Baird et al., 2003), with a two- to three-fold increased risk for development of uterine fibroids in black versus white women (Stewart et al., 2017). Approximately 20–50% of premenopausal women with uterine fibroids exhibit symptoms that may require clinical intervention (Buttram and Reiter, 1981); these symptoms include heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), often associated with iron-deficiency anemia (also called abnormal uterine bleeding due to leiomyoma [AUB-L]) (Stewart, 2001; Munro et al., 2011) and are the most common indication for hysterectomy (Carlson et al., 1993).

The treatment of women with uterine fibroids is individualized based on symptoms, age, desire to preserve fertility and patient preference. Hysterectomy remains the mainstay of treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids in the United States, accounting for >75% of all procedures (Borah et al., 2016). Alternatives to hysterectomy include myomectomy, uterine artery embolisation, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound and short-term pre-operative pharmacologic treatments (Stewart, 2001).

Uterine fibroids respond to estradiol (E2) and progesterone (Carr et al., 1993). Newer research suggests that progesterone and the progesterone receptor (PR) play a more important role, whereas E2 has a permissive role by stimulating PR synthesis (Chwalisz et al., 2005b; Bulun, 2013). The most compelling evidence of the role of progesterone in uterine fibroid growth and development comes from studies showing that selective PR modulators (SPRMs; e.g. mifepristone, asoprisnil and ulipristal acetate) suppress uterine bleeding and reduce fibroid volume (Eisinger et al., 2003; Chwalisz et al., 2007; Wilkens et al., 2008; Donnez et al., 2012a; Ali and Al-Hendy, 2017). Ulipristal acetate was approved initially in the EU and Canada as a pre-operative treatment for symptomatic uterine fibroids (Donnez et al., 2012a; 2012b) and, more recently, for the long-term management of symptomatic uterine fibroids using an intermittent treatment regimen (Donnez et al., 2014).

Asoprisnil is a highly selective 11β-benzaldoxime-substituted SPRM with mixed PR agonist/antagonist activity (Elger et al., 2000; DeManno et al., 2003). Compared with other SPRMs, including mifepristone and ulipristal acetate, asoprisnil showed a higher degree of progesterone agonist versus antagonist activity in animal models (Elger et al., 2000). In cultured leiomyoma cells, asoprisnil inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis, without similarly affecting myometrial cells (Chen et al., 2006; Sasaki et al., 2007) and down-regulated collagen synthesis (Morikawa et al., 2008).

In a Phase 1 study, asoprisnil demonstrated dose-dependent suppression of menstrual bleeding without E2 deprivation (Chwalisz et al., 2005a). In a subsequent 3-month, Phase 2 study in women with HMB associated with uterine fibroids, asoprisnil (5, 10 and 25 mg) suppressed HMB, reduced fibroid and uterine volume, improved hematological parameters in a dose-dependent manner, and had an acceptable safety and tolerability profile (Chwalisz et al., 2007).

This report presents a pooled analysis of the two Phase 3 studies of asoprisnil in women with uterine fibroids and HMB. The objective of these studies was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of two oral doses of asoprisnil (10 mg and 25 mg once daily) compared with placebo over a continuous 12-month treatment period.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This report combines data from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre studies (NCT00152269 [Study 1] and NCT00160381 [Study 2], clinicaltrials.gov) conducted in the United States and Canada between September 2002 and January 2005. Both studies had identical protocols except that bone mineral density (BMD) was evaluated in Study 1.

Ethical approval

The studies were approved by institutional review boards and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and local and federal laws and regulations. An independent data safety monitoring board (DSMB) and panel of endometrial pathologists regularly reviewed safety.

Study population

Participants (N = 907 randomized) were premenopausal women ≥18 years of age who had regular menstrual cycles, defined as 21–42 days, and who agreed to use two forms of non-hormonal contraception throughout the studies. The presence of uterine fibroids with at least one of the following criteria was documented by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): 1 submucosal fibroid with diameter ≥2.0 cm, 1 intramural fibroid with diameter ≥3.5 cm, 1 subserosal fibroid with diameter ≥3.5 cm, or multiple small fibroids with uterine volume ≥200 cm3. HMB was evaluated using a validated semi-quantitative menstrual pictogram (MP) method (Larsen et al., 2013); eligible women had an MP score >80 mL during the screening menstrual cycle or hemoglobin ≤10.5 g/dL at screening and day −1 and had no evidence of malignancy or premalignant changes in screening endometrial biopsies and Pap smears. Study participants were excluded if they were pregnant, were within three months postpartum, used an intrauterine device, had a previous myomectomy within one year or uterine artery embolization within six months of enrollment, or had a history of polycystic ovary syndrome, prolactinomas or malignancy. Additional exclusion criteria were the presence of intracavitary pedunculated fibroids or endometrial polyps (assessed via saline-infusion sonohysterogram) in participants with suspected intracavitary lesions on transvaginal ultrasound [TVU] or MRI), hemoglobin <8 g/dL on Day −1 and, in Study 1, a bone mineral density T-score at or below −2.5 at screening.

Efficacy endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of women who met all of the following criteria at Month 12 or the final month for patients who prematurely discontinued: (1) reduction from baseline of ≥50% in MP score, (2) hemoglobin concentration ≥11 g/dL or increase of ≥1 g/dL from baseline, and (3) no surgical or invasive intervention for uterine fibroids (e.g. hysterectomy, myomectomy and uterine artery embolism) during treatment nor withdrawal from the study with the intention to have such an intervention. This endpoint was designed in consultation with the United States Food and Drug Administration as a surrogate measure of the avoidance of surgical intervention for HMB. Standardized cotton sanitary protection products (Kotex® Super and Nighttime napkins; Tampax® Regular, Super and Super Plus tampons) were provided throughout the studies. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the response rate for the primary efficacy endpoint at Month 6, monthly MP scores, number of days with bleeding or spotting, monthly rates of amenorrhea (i.e. no bleeding during that month), the percentage of participants with suppression of menses (i.e. no menses for ≥60 consecutive days during treatment after the end of randomization menses), maintenance of menses suppression, change from baseline in hemoglobin, hematocrit, ferritin, total iron binding capacity and iron, percentage change from baseline in the volume of each of the two largest fibroids and the uterus at Months 6 and 12, and the Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life (UFS-QOL)(Spies et al., 2002) and Leiomyoma Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (LSAQ) (Chwalisz et al., 2007). MRI was used to measure fibroid and uterine volume at screening, Month 6, Month 12, and the Month-6 follow-up visit. The primary fibroid was the largest fibroid based on volume.

Safety evaluation and endpoints

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded and evaluated throughout the studies. BMD was assessed (Study 1) in the lumbar spine by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) at screening and at Month 12 in a subset of ~300 women. A central service (DXA Resource Group, Inc., Worcester, MA, USA) evaluated DXA scans.

Laboratory evaluations, including safety (general, hepatic, renal) and hematology parameters, were conducted at screening, baseline, and every 2 months during the treatment period. Hematology, iron and select endocrine parameters were also collected at the Month-3 follow-up visit. Hormonal parameters (luteinizing hormone [LH], follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], E2, estrone [E1], progesterone, androstenedione, total and free testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin [SHBG], dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate [DHEA-S], thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH], thyroxine [T4], and prolactin) were measured throughout the studies (supplementary Table SI).

Endometrial assessments

Each endometrial biopsy (from screening, Months 6 and 12, and Month-3 post-treatment) was evaluated by two independent, central pathologists. If their diagnoses were abnormal or discrepant, a third central pathologist provided final arbitration. All readings were conducted blinded to the participant’s treatment and to the other pathologist’s diagnosis. The endometrial biopsy results were assessed according to diagnostic categories that were developed by the panel of expert endometrial pathologists specifically for asoprisnil clinical trials. Briefly, the diagnostic dictionary included two morphologic patterns that were considered specific for selective progesterone receptor modulator effects. ‘Non-physiologic secretory pattern’ referred to endometrial glands in which weak secretory changes were seen that were variable and incomplete, with basally oriented epithelial cell nuclei and minimal or no evidence of proliferation. ‘Secretory pattern – mixed type’ referred to glands with non-physiological secretory activity as above, with additional evidence of proliferative activity (less marked basal orientation of epithelial cell nuclei and more than 1 mitosis per 20 gland profiles). In both patterns, the stroma showed a variable degree of partial secretory differentiation. These categories were used in previous studies with asoprisnil (Chwalisz et al., 2005a, 2007; Williams et al., 2007) and were later included as part of the progesterone receptor modulator associated endometrial changes (PAEC) spectrum (Mutter et al., 2008).

Saline infused sonohysterogram (SIS) was performed in participants with suspected intracavitary lesions on TVU or MRI images at baseline or anytime during the studies. MRI and SIS images were evaluated by blinded, independent central readers (WorldCare Clinical Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA). When indicated, hysteroscopy, dilation and curettage (D&C), and polypectomy were performed to evaluate imaging changes suggestive of a polyp, endometrial thickness ≥19 mm or unsatisfactory endometrial biopsies. Tissue samples obtained during these procedures were evaluated by both local and central pathologists.

Randomization

Eligible women (N = 907) were randomized using a computer-generated randomization chart with a fixed block size of 5 in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive oral asoprisnil 10 mg (n = 370), asoprisnil 25 mg (n = 364) or placebo (n = 173). The study drug was dispensed in blister packs, each with an attached blinded label. Dosing began within the first 5 days of the onset of the woman’s menstrual period and continued once daily for 12 months. Participants, site personnel and the sponsor remained blinded to treatment assignment throughout, including the post-treatment follow-up. At study completion, eligible women could enroll in a 12-month, open-label extension study; women who were ineligible or declined participation in the extension study were followed for 6 months thereafter to allow for the assessment of return to menses and regrowth of leiomyomata. Prohibited medications are listed in supplementary Table SII. Hormonal treatment before study initiation required predefined washout periods (2–12 months, depending on the drug). Women with anemia received iron supplementation to normalize hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels.

Statistical analyses

To calculate the primary endpoint, the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) set was pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan. All women in the mITT set had complete baseline and treatment period data related to calculating the primary endpoint and either (a) were on treatment for at least 30 days or (b) discontinued prior to Day 30 to have surgery for fibroids. In the case of discontinuation to have surgery for fibroids, the woman was considered a non-responder. Pooled efficacy analyses are presented for this mITT set (placebo, n = 153; asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 321; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 317).

Pairwise comparisons of the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints at the participant’s final visit and 6 months, respectively, were performed using the Fisher exact test, using the Hochberg multiple comparison procedure to control the Type I error rate. The mean change from baseline in monthly MP scores, number of days with bleeding, and bleeding or spotting each month were analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. Changes in hemoglobin levels were analyzed using a 1-way ANCOVA with treatment as a factor and baseline level as a covariate. UFS-QOL and LSAQ total and subscale scores were analyzed using the generalized Cochran–Mantel-Haenszel mean score test with baseline score as strata. The percentage change in fibroid and uterine volume was analyzed with a 1-way Kruskal–Wallis analysis with treatment as a factor. Percentages of participants with incremental amenorrhea were compared using the Fisher exact test. Most efficacy analyses were based on changes from baseline to the last assessment, i.e. using the last observation carried forward methodology.

The safety population included all participants who received at least one dose of the study drug. AEs and endometrial biopsy results for all participants were summarized by treatment group; pairwise between-group comparisons were performed using the Fisher exact test. Endometrial thickness, hematology, chemistry, urinalysis and endocrine parameters were summarized descriptively; changes from baseline to each study visit were analyzed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with treatment as a fixed factor and pairwise comparisons were assessed within this model. Safety evaluations are unadjusted for multiple comparisons, and nominal P values are reported.

A sample size of ~375 participants per study (150 participants in each of the asoprisnil 10- and 25-mg arms, respectively, and 75 participants in the placebo arm) would give 90% power to detect a difference between the placebo group and asoprisnil groups assuming rates of 25% and 50%, respectively, for the primary endpoint based on a two-sided α = 0.05 significance level.

Data sharing

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials it sponsors. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets) as well as other information (e.g. protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Results

Study population

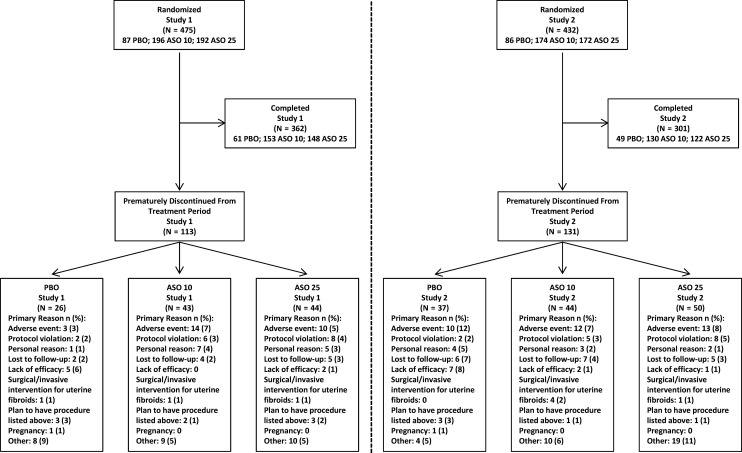

Most participants completed the studies (73%; Fig. 1). The proportions of women who withdrew were higher in the placebo arm (36%) than in the asoprisnil 10-mg (24%) and 25-mg (26%) arms. AEs were the most common reason besides ‘other’ reasons for discontinuation in the asoprisnil arms in both studies and in the placebo arm for Study 2 (Fig. 1 and supplementary Table SIII). The population in the post-treatment follow-up period included only the 238 women who did not enroll in the extension study.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram. ASO 10 = asoprisnil 10 mg once daily; ASO 25 = asoprisnil 25 mg once daily; PBO = placebo.

Most participants were black and were 40 years of age or older (Table I). Participant characteristics, fibroid-related characteristics and hematologic parameters did not differ significantly between groups. Exclusion of randomized patients from primary endpoint analysis due to an MP score ≤80 mL and hemoglobin level >10.5 g/L during screening occurred in small proportions of women in the placebo (6%), asoprisnil 10-mg (5%) and asoprisnil 25-mg (4%) arms.

Table I.

Demographics and baseline characteristics (all randomized participants).

| Characteristic | Study 1 and Study 2 (N = 907) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 173) | Asoprisnil 10 mg (n = 370) | Asoprisnil 25 mg (n = 364) | |

| Race or ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Black | 98 (56.6) | 180 (48.6) | 186 (51.1) |

| White | 64 (37.0) | 162 (43.8) | 148 (40.7) |

| Hispanic | 10 (5.8) | 24 (6.5) | 17 (4.7) |

| Asian | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 6 (1.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 7 (1.9) |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 42.0 (5.6) | 42.8 (5.2) | 43.1 (5.6) |

| Mean (SD) BMI, kg/m2,a | 29.9 (6.92) | 29.3 (6.44) | 29.4 (6.46) |

| Mean (SD) primary fibroid volume, cm3,b | 168.7 (238.1) | 189.2 (294.5) | 155.2 (187.6) |

| Primary fibroid location, n (%)b | |||

| Intramural | 102 (68.0) | 216 (63.9) | 196 (58.9) |

| Pedunculated submucosal | 1 (0.7) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) |

| Pedunculated subserosal | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Submucosal | 28 (18.7) | 92 (27.2) | 104 (31.2) |

| Subserosal | 16 (10.7) | 26 (7.7) | 30 (9.0) |

| Mean (SD) uterine volume, cm3,c | 542.8 (430.5) | 656.6 (546.6) | 588.6 (454.1) |

| Mean (SD) MP total score, mLd | 283.6 (293.3) | 263.8 (213.3) | 283.3 (260.4) |

| Anemic, n (%)e | 71 (41.5) | 151 (41.7) | 196 (55.1) |

| Mean (SD) hemoglobin, g/dLe | 12.0 (1.7) | 12.0 (1.8) | 11.8 (1.7) |

BMI = body mass index; MP = menstrual pictogram.

aPlacebo, n = 171; asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 364; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 362.

bPlacebo, n = 150; asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 338; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 333.

cAsoprisnil 10 mg, n = 366; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 362.

dPlacebo, n = 171; asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 363; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 359.

ePlacebo, n = 171; asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 362; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 356. Hemoglobin <12 g/dL was considered to indicate anemia.

Efficacy endpoints

In all, 90% and 93% of women in the asoprisnil 10-mg and 25-mg groups, respectively, met the primary efficacy endpoint compared with 35% of women in the placebo group (P < 0.001; Table II). Similar results were observed at Month 6 (P < 0.001; Table II).

Table II.

Efficacy outcomes (mITT population).

| Study 1 and Study 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Placebo (n = 153) | Asoprisnil 10 mg (n = 321) | P values | Asoprisnil 25 mg (n = 317) | P values |

| Primary endpoint response rate, n/M (%) | |||||

| Month 6 | 44/153 (29) | 291/321 (91) | <0.001a | 294/315 (93) | <0.001a |

| Month 12 | 53/153 (35) | 288/321 (90) | <0.001a | 295/317 (93) | <0.001a |

| Monthly MP score: Mean change from baseline, mL (SD) | |||||

| Month 6 | −112.3 (246.43) | −250.7 (194.97) | <0.001b | −296.9 (265.60) | <0.001b |

| n = 119 | n = 288 | n = 283 | |||

| Month 12 | −106.0 (270.70) | −256.2 (201.62) | <0.001b | −303.5 (284.49) | <0.001b |

| n = 98 | n = 254 | n = 233 | |||

| Number of days with bleeding: Mean change from baseline, days (SD) | |||||

| Month 6 | −1.1 (3.62) | −6.2 (3.59) | <0.001b | −7.0 (3.40) | <0.001b |

| n = 119 | n = 288 | n = 283 | |||

| Month 12 | −1.4 (3.56) | −6.4 (3.78) | <0.001b | −7.0 (3.86) | <0.001b |

| n = 97 | n = 254 | n = 233 | |||

| Suppression of menses, n/M (%) | |||||

| Treatment period | 14/151 (9) | 281/315 (89) | NC | 294/305 (96) | NC |

| Maintenance of suppression of menses after initial suppression, n/M (%) | |||||

| Treatment period | 8/151 (5) | 228/315 (72) | NC | 265/305 (87) | NC |

| Hemoglobin: Mean change from baseline, g/dL (SD) | |||||

| Month 6 | 0.3 (1.35) | 1.6 (1.66) | <0.001b | 1.7 (1.63) | <0.001b |

| n = 109 | n = 259 | n = 255 | |||

| Month 12 | 0.0 (1.40) | 1.6 (1.72) | <0.001b | 1.8 (1.75) | <0.001b |

| n = 86 | n = 222 | n = 214 | |||

| UFS-QOL symptom severity score: Mean change from baseline (SD) | |||||

| Month 6 | −15.5 (22.47) | −37.0 (21.51) | <0.001b | −46.2 (21.49) | <0.001b |

| n = 120 | n = 276 | n = 271 | |||

| Month 12 | −13.6 (23.91) | −39.3 (19.72) | <0.001b | −46.9 (20.60) | <0.001b |

| n = 94 | n = 239 | n = 230 | |||

| UFS-QOL HRQL total score: Mean change from baseline (SD) | |||||

| Month 6 | 19.8 (25.08) | 37.6 (24.65) | <0.001b | 44.1 (23.44) | <0.001b |

| n = 114 | n = 271 | n = 268 | |||

| Month 12 | 13.7 (23.84) | 39.8 (23.63) | <0.001b | 46.5 (23.97) | <0.001b |

| n = 92 | n = 236 | n = 226 | |||

M = number of participants included in the primary endpoint analysis per given subcategory; HRQL = health-related quality of life; mITT = modified intent-to-treat; MP = menstrual pictogram; NC = not calculated; UFS-QOL = Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life.

aP < 0.001 statistically significant difference vs placebo using the Hochberg multiple comparison procedure with an initial critical P = 0.05 (from the Fisher exact test).

bP < 0.001 statistically significant difference vs placebo using the Hochberg multiple comparison procedure with an initial critical P = 0.05 (from the contrasts within the framework of the analysis of covariance model with baseline as a covariate and treatment as a fixed factor).

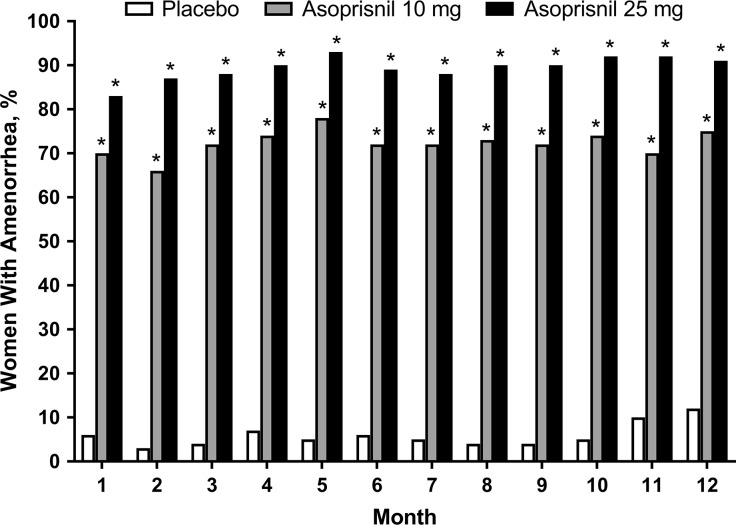

Menstrual bleeding parameters

The mean monthly blood loss (MBL), or MP score, was consistently and significantly (P < 0.001) reduced to <21 mL and <13 mL by asoprisnil 10 and 25 mg, respectively, versus placebo in Month 1 through to Month 12 of treatment (Fig. 2; Table II). There were also significant (P < 0.001) reductions in the number of days with bleeding (Table II) and in the number of days with bleeding or spotting (supplementary Fig. S1) in both asoprisnil groups throughout treatment. Monthly amenorrhea rates (Fig. 3) and suppression of menses rates (Table II) were significantly higher (P < 0.001) for both asoprisnil groups. After stopping treatment, 73–87% and 53–66% of women treated with asoprisnil 10 mg and asoprisnil 25 mg, respectively, experienced return of menses within 1 month across the studies. Mean MBL during the first post-treatment menses was similar to baseline in both the asoprisnil 10-mg and 25-mg groups and in the placebo group, indicating a return toward baseline HMB (supplementary Table SIV).

Figure 2.

Mean menstrual pictogram score in mL (modified intent-to-treat population). BL = baseline. *P < 0.001 statistically significant difference for asoprisnil 10 mg or 25 mg versus placebo for change from baseline, using the Hochberg multiple comparison procedure with an initial critical P = 0.05 (from the Fisher exact test). Error bars represent 2× the standard error of the mean.

Figure 3.

Percentage of women with incremental amenorrhea by month (modified intent-to-treat population). *P < 0.001 statistically significant difference for asoprisnil 10 mg or 25 mg versus placebo, using the Hochberg multiple comparison procedure with an initial critical P = 0.05 (from the Fisher exact test).

Hematologic and iron parameters

Hemoglobin and other hematologic parameters increased rapidly in the asoprisnil groups and were sustained throughout treatment. The mean increases from baseline at Month 6 and Month 12 were significantly greater (P < 0.001) with the asoprisnil groups compared with placebo (Table II and supplementary Table SV).

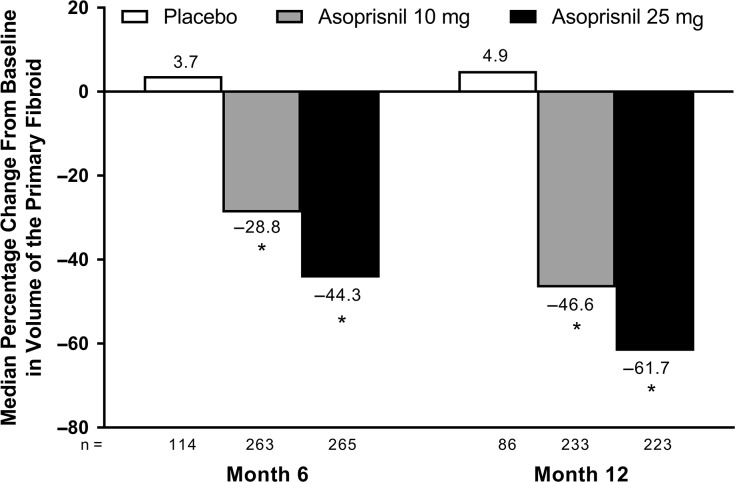

Fibroid and uterine volume

Compared with baseline, the volume of the primary fibroid was significantly reduced in women receiving asoprisnil (10 or 25 mg) versus placebo at 6 and 12 months (P < 0.001; Fig. 4); this effect was maintained post-treatment. Median changes from baseline in primary fibroid volume at post-treatment Month 6 were up to −45% with asoprisnil 10 mg and −54% with asoprisnil 25 mg versus up to 44% with placebo. Median changes in uterine volume were as large as −28% with asoprisnil 10 mg and −39% with asoprisnil 25 mg at Month 6 and Month 12 versus 13% with placebo (P < 0.001). Uterine volume reductions were substantially maintained post-treatment, especially in the asoprisnil 25-mg group; median changes from baseline in uterine volume at post-treatment Month 6 were up to −6% with asoprisnil 10 mg and −29% with asoprisnil 25 mg versus –25% to 50% with placebo.

Figure 4.

Median percentage change in volume of the largest fibroid (modified intent-to-treat population). *P < 0.001 statistically significant difference versus placebo, using the Hochberg multiple comparison procedure with an initial critical P = 0.05 (from the Kruskal–Wallis large-sample approximation test).

Patient-reported outcomes

The UFS-QOL symptom severity score and health-related quality-of-life (HRQL) total score at Month 6 and Month 12 were significantly improved in women treated with asoprisnil versus placebo (P < 0.001;Table II). All six HRQL subscales showed similar results (supplementary Tables SVI and SVII). Significant improvements in bloating, pelvic pressure and dysmenorrhea as measured by LSAQ were observed by Month 2 for both asoprisnil groups compared with placebo, and these effects were maintained through Month 12 (P < 0.001; supplementary Table SVIII).

Safety and tolerability

General safety

The percentage of women who reported ≥1 AE was similar among groups (Table III). Hot flushes occurred more frequently in the asoprisnil groups and were significantly increased with the 25-mg dose compared with placebo (14% vs 7%; P < 0.05). Other AEs were infrequent, but bladder and urethral symptoms and myalgias were significantly increased with asoprisnil treatment, while menstrual symptoms and nonspecific muscle symptoms were decreased, compared with placebo. No pregnancies occurred in asoprisnil-treated women.

Table III.

Most frequently reported adverse events (safety population).

| MedDRA high-level term | Study 1 and Study 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MedDRA preferred terms | Placebo (n = 173) | Asoprisnil 10 mg, (n = 370) | Asoprisnil 25 mg, (n = 364) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total participants with ≥1 adverse event, n (%) | 145 (84) | 337 (91) | 321 (88) |

| Upper respiratory tract infections | 44 (25) | 92 (25) | 94 (26) |

| Acute sinusitis, laryngitis, nasopharyngitis, pharyngitis, rhinitis, sinusitis, tonsillitis, upper respiratory tract infection | |||

| Headaches NEC | 44 (25) | 102 (28) | 92 (25) |

| Headache, sinus headache, tension headache | |||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue signs and symptoms NEC | 31 (18) | 84 (23) | 70 (19) |

| Back pain, chest wall pain, flank pain, musculoskeletal discomfort, musculoskeletal stiffness, neck pain, nodule on extremity, pain in extremity, sensation of heaviness, shoulder pain | |||

| Peripheral vascular disorders NEC | 12 (7) | 35 (9) | 52 (14)a |

| Flushing, hot flush | |||

| Nausea and vomiting symptoms | 20 (12) | 48 (13) | 32 (9) |

| Nausea, vomiting | |||

| Vulvovaginal signs and symptoms | 16 (9) | 36 (10) | 39 (11) |

| Genital pruritus female, postcoital bleeding, vaginal burning sensation, vaginal discharge, vaginal lesion, vaginal odor, vaginal pain, vulvovaginal discomfort, vulvovaginal dryness | |||

| Breast signs and symptoms | 10 (6) | 39 (11) | 24 (7) |

| Breast discharge, breast discomfort, breast engorgement, breast pain, breast swelling, breast tenderness, nipple pain | |||

| Gastrointestinal and abdominal pains (excluding oral and throat) | 15 (9) | 35 (9) | 39 (11) |

| Abdominal pain, abdominal pain lower, abdominal pain upper, abdominal tenderness | |||

| Joint-related signs and symptoms | 8 (5) | 29 (8) | 22 (6) |

| Arthralgia, joint stiffness, joint swelling, temporomandibular joint syndrome | |||

| Fungal infections NEC | 8 (5) | 15 (4) | 25 (7) |

| Fungal infection, onychomycosis, vaginal mycosis | |||

| Influenza viral infections | 10 (6) | 31 (8) | 24 (7) |

| Influenza | |||

| Menstruation and uterine bleeding NEC | 12 (7) | 5 (1)b | 4 (1)b |

| Dysmenorrhaea | |||

| Muscle-related signs and symptoms NEC | 10 (6) | 8 (2)a | 6 (2)a |

| Muscle fatigue, muscle spasm, muscle tightness, muscle twitching | |||

| Pain and discomfort NEC | 8 (5) | 25 (7) | 21 (6) |

| Chest pain, pain | |||

| Bacterial infections NEC | 12 (7) | 20 (5) | 25 (7) |

| Cellulitis, upper respiratory tract infection bacterial, vaginitis bacterial | |||

| Bladder and urethral symptoms | 3 (2) | 29 (8)c | 23 (6)a |

| Bladder spasm, dysuria, micturition urgency, pollakiuria, stress incontinence, urge incontinence, urinary incontinence | |||

| Flatulence, bloating, and distension | 5 (3) | 22 (6) | 23 (6) |

| Abdominal distension, flatulence | |||

| Muscle pains | 3 (2) | 21 (6)a | 23 (6)a |

| Myalgia | |||

| Upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms | 3 (2) | 22 (6)a | 14 (4) |

| Nasal discomfort, pharyngolaryngeal pain, rhinorrhea, throat irritation, throat tightness | |||

| Asthenic conditions | 7 (4) | 15 (4) | 20 (5) |

| Asthenia, fatigue, malaise | |||

| Edema NEC | 9 (5) | 12 (3) | 9 (2) |

| Generalized edema, edema, edema peripheral, pitting edema | |||

| Reproductive tract signs and symptoms NEC | 8 (5) | 20 (5) | 14 (4) |

| Genital rash, hydrometra, pelvic pain, premenstrual syndrome | |||

MedDRA = Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; NEC = not elsewhere classified.

Most frequent was defined as those high-level terms reported by ≥5% of participants in any treatment group. Includes all adverse events from the start of the study drug through 30 days postdosing.

aP < 0.05 statistical significance vs placebo, using the Fisher exact test.

bP < 0.001 statistical significance vs placebo, using the Fisher exact test.

cP < 0.01 statistical significance vs placebo, using the Fisher exact test.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (reported as uterine hemorrhage; asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 1; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 1) and cholecystitis (asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 2) were the only serious AEs experienced by more than one woman in either study. All AEs leading to discontinuation are presented in supplementary Table SIII. Six women discontinued because of increases in the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase (asoprisnil 10 mg, n = 2 [starting Days 60 and 182]; asoprisnil 25 mg, n = 3 [Days 56, 61, and 63]; placebo, n = 1 [Day 115]), one woman discontinued because of an increase in gamma-glutamyl transferase (placebo [Day 117]), and one woman with a history of Gilbert’s syndrome (asoprisnil 10 mg [Day 137]) discontinued because of isolated increases in total bilirubin. In most women, the increases in liver enzymes were mild (2–3× the upper limit of normal) and transient; none of these events was associated with an increase in total bilirubin or symptoms.

Endometrial assessments

Endometrial biopsy results

Endometrial biopsy results are presented in supplementary Table SIX. SPRM-specific categories (‘non-physiologic secretory effect’ and ‘secretory pattern, mixed type’) were significantly increased with asoprisnil treatment at 6 and 12 months and ranged between 8% and 19% (placebo 1–4%), with no differences between asoprisnil doses. With asoprisnil treatment, there was a dose- and time-dependent decrease in the frequency of diagnoses consistent with active proliferation, with ‘inactive’ endometrium being the dominant diagnosis (28–32%) at Month 12 of treatment, compared with placebo (3%). There were two adverse endometrial findings: one woman, who had a history of endometrial hyperplasia, was diagnosed with complex hyperplasia without atypia at the Month 6 biopsy (asoprisnil 10 mg), and a second woman (asoprisnil 25 mg) was diagnosed with low-grade endometrial adenosarcoma in an endometrial polyp at Month 9. Both of these changes were seen in the setting of an increase in endometrial thickness. Retrospective examination of the baseline MRI images of the woman with adenosarcoma did show a focal endometrial lesion, which suggests a potential pre-existing condition (supplementary Tables SX and SXI).

In the limited population of women who entered the post-treatment follow-up period, the endometrium of the vast majority of asoprisnil-treated women returned to normal cyclic physiologic patterns by post-treatment Month 3 (supplementary Table SIX). Only 5% and 2% of women treated with asoprisnil at post-treatment Month 3 follow-up were diagnosed with ‘non-physiologic secretory effect’ and ‘secretory pattern, mixed type,’ respectively.

Changes in endometrial thickness and texture

There was no significant increase in mean endometrial thickness at Months 4 and 8 in both asoprisnil groups compared with placebo when measured with TVU (supplementary Table SX). However, there was a slight but significant (P < 0.01) increase from baseline (~2 mm) at Month 12 in women receiving asoprisnil compared with placebo when measured with MRI (supplementary Table SXI).

The analysis of MRI and TVU images revealed dose- and time-dependent increases in the percentage of women with endometrial thickness ≥19 mm at Month 8 and the presence of cystic changes (mostly endometrial cysts and polypoid changes), which somewhat mimicked imaging findings of endometrial hyperplasia (supplementary Table SXII). These changes contributed to the notable increase in the rate of invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, including hysteroscopy, D&C and polypectomy, in the asoprisnil groups (7–10%) after Month 8 compared with the placebo group (0%).

Laboratory safety parameters

No clinically meaningful changes in general chemistry, renal, and hepatic parameters were observed with asoprisnil treatment. There was little change in total cholesterol associated with asoprisnil treatment; however, asoprisnil significantly reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in a dose- and time-dependent manner (supplementary Table SXIII).

Endocrine and bone parameters

A modest, dose-dependent inhibitory effect of asoprisnil on basal FSH and LH was observed at Month 12 (supplementary Table SXIV). There was a dose-dependent reduction over time in E2 (supplementary Fig. S2) and E1 in asoprisnil groups. However, most E2 levels remained in the early follicular phase range. Total testosterone, androstenedione and SHBG decreased slightly but significantly more from baseline with either asoprisnil dose versus placebo at 6 and 12 months (supplementary Table SXIV). No significant differences in the mean percentage BMD change from baseline to Month 12 were observed with asoprisnil treatment compared with placebo (Study 1).

Discussion

In these two randomized, placebo-controlled studies, uninterrupted treatment with asoprisnil for 12 months effectively controlled HMB, improving anemia, quality of life, and non-bleeding symptoms, and reducing the fibroid and uterine volumes in women with HMB and fibroids. The primary endpoint was achieved in ≥90% of women treated with asoprisnil compared with 35% of women in the placebo group. The effects were rapid, dose dependent, and maintained during the entire treatment period, with amenorrhea rates ranging between 66% and 93% and low occurrence of breakthrough bleeding or spotting. The effects of asoprisnil on HMB reversed after stopping treatment.

These results are consistent with other SPRMs, including mifepristone and ulipristal acetate (Murphy et al., 1993; Kettel et al., 1994; Donnez et al., 2012a, 2014), and with earlier asoprisnil studies (Chwalisz et al., 2005a, 2007; Wilkens et al., 2008). However, amenorrhea rates in the present studies seem higher than with ulipristal acetate, particularly in the US population (Soper et al., 2017). This increased efficacy may be related to our hypothesis that asoprisnil controls HMB via a dual mechanism by directly affecting the endometrium and indirectly inhibiting ovulation (Chwalisz et al., 2005a). Subsequent mechanistic studies have suggested that the endometrial effect of asoprisnil occurs via suppression of the uterine NK cells that regulate the function of spiral arteries (Wilkens et al., 2013).

We also observed significant, progressive reduction in fibroid and uterine volumes, with slow regrowth of uterine fibroids after stopping treatment, which could be due to the selective antiproliferative, proapoptotic effects and inhibition of extracellular matrix formation in uterine fibroids by asoprisnil (Ohara et al., 2007; Sasaki et al., 2007; Morikawa et al., 2008) or other effects including the reduction in uterine blood flow (Wilkens et al., 2008). Similarly, durable reduction of fibroid volume was observed after short-term treatment with ulipristal acetate (Donnez et al., 2014).

Treatment with asoprisnil for up to 12 months was not associated with any general safety issues, including hepatic safety. No cases of liver injury were reported during these placebo-controlled studies. The small increase in the rate of hot flushes (Table III) could be attributed to the reduction in E2 levels. The BMD evaluation (Study 1) revealed no significant changes versus placebo at Month 12.

At no point throughout the studies did the endometrial biopsy results, which were thoroughly monitored by both the endometrial pathology safety panel and DSMB, raise any safety concerns. The endometrial effects induced by asoprisnil in endometrial biopsies were viewed as unique but benign changes.

In these studies, treatment with asoprisnil was associated with a time-dependent progression of endometrial changes on both endometrial biopsies and images, becoming clinically evident after ≥8 months of treatment (supplementary Tables SX to SXII), which led to an increase in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Both the endometrial biopsy results and textural change on TVU and MRI images seemed to reverse after stopping therapy at Month 3 of the follow-up period, with resumption of menses.

A strength of this study is the high percentage of black women, whose disease course is earlier and more severe compared with white women (Baird et al., 2003; Huyck et al., 2008; Jacoby et al., 2010; Laughlin et al., 2010; Bulun, 2013). Additionally, the HMB was severe, with mean and median MBL of >260 mL and ~200 mL, respectively. Additional strengths include use of validated sanitary products for bleeding assessments, thorough endometrial assessments involving expert endometrial pathologists, and the use of MRI to assess changes in fibroid and uterine volumes. A major weakness was limited follow-up data because most patients transferred to the open-label, uncontrolled long-term extension study; this is described separately (Diamond et al., submitted for publication, 2019). Additionally, hematologic analyses could be confounded by iron supplementation to normalize hemoglobin levels. Finally, although the current sponsor is committed to publication of all its interventional clinical trials conducted in patients, reports of these trials conducted >10 years ago had been delayed for multiple reasons including multiple changes in sponsor and indeterminate development plans. Despite this delay, these data are clinically important because they represent the only studies with an SPRM that used a continuous (uninterrupted) treatment regimen for 12 months.

In summary, asoprisnil treatment was highly effective in controlling bleeding, improving anemia, reducing fibroid and uterine volume, and increasing quality of life in women with HMB associated with uterine fibroids. The safety profile, including hepatic function, was acceptable. However, uninterrupted treatment with the SPRM asoprisnil may pose a safety concern because of the unknown long-term endometrial effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the late Craig A. Winkel, MD, of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA, for his contributions to the study, conduct as a medical director for TAP, and critical review of the manuscript. Jillian Gee, PhD, John Fincke, PhD, and Erin P. Scott, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, North Wales, PA, USA, provided medical writing and editorial support, funded by AbbVie Inc. The authors thank all of the trial investigators and the women who participated in these trials.

Authors’ roles

E.A. Stewart participated in study design, data analysis and preparation, critical review and approval of the manuscript. M.P. Diamond participated in study conduct, data analysis and preparation, critical review and approval of the manuscript. A.R.W. Williams was a member of the independent endometrial pathology consultant panel in these studies. He was involved in drafting, critical review and approval of the manuscript. B.R. Carr participated in collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and in critically reviewing and approving the manuscript. E.R. Myers participated in interpretation of data and critical review and approval of the manuscript. R.A. Feldman served as a principal investigator and participated in the conduct of the trials and participated in critical review and approval of the manuscript. W. Elger proposed the concept of a PR-agonistic PRM. A respective collaboration eventually led to the discovery of asoprisnil and mechanistic insights into its mode of action. (He participated in the analysis of hormonal properties and related findings throughout preclinical and clinical exploration.) He contributed to historical aspects and viewpoints concerning PRM pharmacology for the manuscript and in critical review and approval of the manuscript. C. Mattia-Goldberg participated in study design, study execution, data clean-up and analysis and critical review and approval of the manuscript. B.M. Schwefel participated in analysis and in drafting, critical review and approval of the manuscript. K. Chwalisz was the medical director of these studies. He participated in designing and conducting the studies, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and in critical review and approval of the manuscript.

Funding

AbbVie Inc. (previously, TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc.) sponsored the studies and contributed to the study design and conduct, data management, data analysis, interpretation of the data and the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

E.A. Stewart was a site investigator in the Phase 2 study of asoprisnil and consulted for TAP during the design and conduct of these studies while at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She received support from National Institutes of Health grants HD063312, HS023418 and HD074711 and research funding, paid to Mayo Clinic for patient care costs related to an NIH-funded trial from InSightec Ltd. She consulted for AbbVie, Allergan, Bayer HealthCare AG, Gynesonics, and Welltwigs. She received royalties from UpToDate and the Med Learning Group. M.P. Diamond received research funding for the conduct of the studies paid to the institution and consulted for AbbVie. He is a stockholder and board and director member of Advanced Reproductive Care. He has also received funding for study conduct paid to the institution from Bayer and ObsEva. A.R.W. Williams consulted for TAP and Repros Therapeutics Inc. He has current consultancies with PregLem SA, Gedeon Richter, HRA Pharma and Bayer. B.R. Carr consulted for and received research funding from AbbVie. E.R. Myers consulted for AbbVie, Allergan and Bayer. R.A. Feldman received compensation for serving as a principal investigator and participating in the conduct of the trial. W. Elger was co-inventor of several patents related to asoprisnil. C. Mattia-Goldberg is a former employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock or stock options. B.M. Schwefel is an employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock or stock options. K. Chwalisz is an employee of AbbVie Inc., the sponsor of the published clinical trials, and may possess company’s stock and stock options. In addition, K. Chwalisz has a patent ‘Mesoprogestins for the treatment and prevention of benign hormone dependent gynecological disorders’ (Inventors; Chwalisz K., Elger W., Schubert G.; EP1229906B1) issued.

References

- Ali M, Al-Hendy A. Selective progesterone receptor modulators for fertility preservation in women with symptomatic uterine fibroids. Biol Reprod 2017;97:337–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, Yao X, Stewart EA. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulun SE. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1344–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttram VC Jr, Reiter RC. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril 1981;36:433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KJ, Nichols DH, Schiff I. Indications for hysterectomy. N Engl J Med 1993;328:856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr BR, Marshburn PB, Weatherall PT, Bradshaw KD, Breslau NA, Byrd W, Roark M, Steinkampf MP. An evaluation of the effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and medroxyprogesterone acetate on uterine leiomyomata volume by magnetic resonance imaging: a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;76:1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Ohara N, Wang J, Xu Q, Liu J, Morikawa A, Sasaki H, Yoshida S, Demanno DA, Chwalisz Ket al. A novel selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil (J867) inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells in the absence of comparable effects on myometrial cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:1296–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwalisz K, Elger W, Stickler T, Mattia-Goldberg C, Larsen L. The effects of 1-month administration of asoprisnil (J867), a selective progesterone receptor modulator, in healthy premenopausal women. Hum Reprod 2005. a;20:1090–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwalisz K, Larsen L, Mattia-Goldberg C, Edmonds A, Elger W, Winkel CA. A randomized, controlled trial of asoprisnil, a novel selective progesterone receptor modulator, in women with uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril 2007;87:1399–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwalisz K, Perez MC, Demanno D, Winkel C, Schubert G, Elger W. Selective progesterone receptor modulator development and use in the treatment of leiomyomata and endometriosis. Endocr Rev 2005. b;26:423–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeManno D, Elger W, Garg R, Lee R, Schneider B, Hess-Stumpp H, Schubert G, Chwalisz K. Asoprisnil (J867): a selective progesterone receptor modulator for gynecological therapy. Steroids 2003;68:1019–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnez J, Tatarchuk TF, Bouchard P, Puscasiu L, Zakharenko NF, Ivanova T, Ugocsai G, Mara M, Jilla MP, Bestel Eet al. Ulipristal acetate versus placebo for fibroid treatment before surgery. N Engl J Med 2012. a;366:409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnez J, Tomaszewski J, Vazquez F, Bouchard P, Lemieszczuk B, Baro F, Nouri K, Selvaggi L, Sodowski K, Bestel Eet al. Ulipristal acetate versus leuprolide acetate for uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med 2012. b;366:421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnez J, Vazquez F, Tomaszewski J, Nouri K, Bouchard P, Fauser BC, Barlow DH, Palacios S, Donnez O, Bestel Eet al. Long-term treatment of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1565–1573 e1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinger SH, Meldrum S, Fiscella K, le Roux HD, Guzick DS. Low-dose mifepristone for uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger W, Bartley J, Schneider B, Kaufmann G, Schubert G, Chwalisz K. Endocrine pharmacological characterization of progesterone antagonists and progesterone receptor modulators with respect to PR-agonistic and antagonistic activity. Steroids 2000;65:713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyck KL, Panhuysen CI, Cuenco KT, Zhang J, Goldhammer H, Jones ES, Somasundaram P, Lynch AM, Harlow BL, Lee Het al. The impact of race as a risk factor for symptom severity and age at diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata among affected sisters. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:168 e1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby VL, Fujimoto VY, Giudice LC, Kuppermann M, Washington AE. Racial and ethnic disparities in benign gynecologic conditions and associated surgeries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:514–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettel LM, Murphy AA, Morales AJ, Yen SS. Clinical efficacy of the antiprogesterone RU486 in the treatment of endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Hum Reprod 1994;9:116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen L, Coyne K, Chwalisz K. Validation of the menstrual pictogram in women with leiomyomata associated with heavy menstrual bleeding. Reprod Sci 2013;20:680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin SK, Schroeder JC, Baird DD. New directions in the epidemiology of uterine fibroids. Semin Reprod Med 2010;28:204–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa A, Ohara N, Xu Q, Nakabayashi K, DeManno DA, Chwalisz K, Yoshida S, Maruo T. Selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil down-regulates collagen synthesis in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells through up-regulating extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer. Hum Reprod 2008;23:944–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS, Group FMDW . The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2204–2208. 2208 e1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AA, Kettel LM, Morales AJ, Roberts VJ, Yen SS. Regression of uterine leiomyomata in response to the antiprogesterone RU 486. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;76:513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutter GL, Bergeron C, Deligdisch L, Ferenczy A, Glant M, Merino M, Williams AR, Blithe DL. The spectrum of endometrial pathology induced by progesterone receptor modulators. Mod Pathol 2008;21:591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara N, Morikawa A, Chen W, Wang J, DeManno DA, Chwalisz K, Maruo T. Comparative effects of SPRM asoprisnil (J867) on proliferation, apoptosis, and the expression of growth factors in cultured uterine leiomyoma cells and normal myometrial cells. Reprod Sci 2007;14:20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Ohara N, Xu Q, Wang J, DeManno DA, Chwalisz K, Yoshida S, Maruo T. A novel selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil activates tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-mediated signaling pathway in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells in the absence of comparable effects on myometrial cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:616–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper D, Lukes AS, Gee P, Kimble T, Kroll R, Mallick M, Chan A, Sniukiene V, Shulman LP, Liu J. Ulipristal acetate (UPA) treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids (UF): VENUS II subgroup analyses by race and BMI. Fertil Steril 2017;108:e28. [Google Scholar]

- Spies JB, Coyne K, Guaou Guaou N, Boyle D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves SM. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet 2001;357:293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, Schulze-Rath R. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG 2017;124:1501–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens J, Chwalisz K, Han C, Walker J, Cameron IT, Ingamells S, Lawrence AC, Lumsden MA, Hapangama D, Williams ARet al. Effects of the selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil on uterine artery blood flow, ovarian activity, and clinical symptoms in patients with uterine leiomyomata scheduled for hysterectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4664–4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens J, Male V, Ghazal P, Forster T, Gibson DA, Williams AR, Brito-Mutunayagam SL, Craigon M, Lourenco P, Cameron ITet al. Uterine NK cells regulate endometrial bleeding in women and are suppressed by the progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil. J Immunol 2013;191:2226–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Critchley HO, Osei J, Ingamells S, Cameron IT, Han C, Chwalisz K. The effects of the selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil on the morphology of uterine tissues after 3 months treatment in patients with symptomatic uterine leiomyomata. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1696–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.