Abstract

OBJECTIVES

This study compares the uniportal with the 3-portal video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) by examining the data collected in the Italian VATS Group Database. The primary end point was early postoperative pain; secondary end points were intraoperative and postoperative complications, surgical time, number of dissected lymph nodes and length of stay.

METHODS

This was an observational, retrospective, cohort, multicentre study on data collected by 49 Italian thoracic units. Inclusion criteria were clinical stage I–II non-small-cell lung cancer, uniportal or 3-portal VATS lobectomy and R0 resection. Exclusion criteria were cT3 disease, previous thoracic malignancy, induction therapy, significant comorbidities and conversion to other techniques. The pain parameter was dichotomized: the numeric rating scale ≤3 described mild pain, whereas the numeric rating scale score >3 described moderate/severe pain. The propensity score-adjusted generalized estimating equation was used to compare the uniportal with 3-portal lobectomy.

RESULTS

Among 4338 patients enrolled from January 2014 to July 2017, 1980 met the inclusion criteria; 1808 patients underwent 3-portal lobectomy and 172 uniportal surgery. The adjusted generalized estimating equation regression model using the propensity score showed that over time pain decreased in both groups (P < 0.001). There was a statistical difference on the second and third postoperative days; odds ratio (OR) 2.28 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.62–3.21; P < 0.001] and OR 2.58 (95% CI 1.74–3.83; P < 0.001), respectively. The uniportal-VATS group had higher operative time (P < 0.001), shorter chest drain permanence (P < 0.001) and shorter length of stay (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Data from the Italian VATS Group Database showed that in clinical practice uniportal lobectomy seems to entail a higher risk of moderate/severe pain on second and third postoperative days.

Keywords: Video-assisted thoracic surgery, Lobectomy, Uniportal, Three-portal, Postoperative pain, Italian VATS Group

INTRODUCTION

First proposed more than 25 years ago, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) lobectomy is a well-established approach for the treatment of early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that gained the ‘grade 2C’ recommendation as a preferred technique over open surgery by the American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based guidelines in 2013 [1, 2]. It is a current opinion that VATS lobectomy results in less pain, fewer complications and more rapid return to normal functioning when compared with open surgery; these assumptions are validated by trial meta-analyses, even though most of those trials were not randomized [3, 4]. To be precise, ‘VATS lobectomy’ is a term covering a series of surgical approaches that vary significantly in the number of incisions, in the width of utility incision and in the way of dealing with the pulmonary hilum; in addition, some imaginative techniques were described, such as the transcervical [5] or the subxiphoid uniportal approaches [6] and microlobectomy [7]. Nevertheless, the 3-portal anterior approach described by Hansen and Petersen [8] is the most popular technique; yet, if VATS lobectomy were superior to open thoracotomy due to minimal surgical access trauma, an additional reduction in such access trauma should lead to better outcomes. This consideration prompted Diego Gonzales Rivas to propose his uniportal VATS (u-VATS) lobectomy in 2010 [9]. Accepted with scepticism, the uniportal technique has spread exponentially, especially in Asian countries. Those who endorse the technique argue that uniportal VATS can decrease postoperative pain and morbidity, and accelerate functional recovery [10]. Despite the publication of some retrospective studies comparing uniportal to ‘multiportal’ VATS lobectomy, there is not enough evidence to determine, which technique should be preferred, especially to reduce postoperative pain [11–16].

The purpose of this study was to compare perioperative outcomes between 3-portal and uniportal VATS lobectomy for early-stage NSCLC by analysing the Italian VATS Group Database.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was an observational, retrospective, cohort, multicentre study on data collected by 49 Italian thoracic surgical units. The Italian VATS Group Database is an online voluntary database launched on l January 2014. This database is open to all Italian thoracic surgery units after approval from the Italian VATS Group Database Committee; this Committee verifies whether each centre has completed the learning curve. The database collects all the VATS lobectomies performed with specific technical requirements: all VATS techniques are included, with utility incision up to 6 cm, without rib spreading and a soft tissue divaricator is allowed. Surgeons operate exclusively through the video equipment; hilar structures must be individually dissected, a standard lymphadenectomy is required and the surgical specimen must be removed with an endobag, avoiding contact with the chest wall incision. Collected data are periodically audited to verify their correspondence to the original data source. Clinical and pathological staging were recorded using the American Joint Committee on Cancer seventh edition TNM classifications until 31 December 2017; a data conversion to the eighth edition is planned in the near future. Variable definitions within the data set are standardized and data entry consistency is ensured by the use of a dropdown menu.

The present study protocol was submitted to the Italian VATS Group Database Committee for approval; therefore, the data collection and study protocol were approved by the local ethics committee (n.723Bis) and the participating patients were requested to sign a written consent.

A data set containing clinical records from patients who received VATS lobectomy from January 2014 to July 2017 was obtained; patients and centres data were anonymized.

Inclusion criteria were clinical stage I–II NSCLC, 3-portal or u-VATS lobectomy and R0 resection. Exclusion criteria were previous thoracic surgery, cT3 disease, previous thoracic malignancy, induction therapy, connective tissue disease, peripheral vascular disease, dementia and diabetes mellitus with organ damage and conversion to other techniques. The primary outcome was pain measured with the numeric rating scale (NRS); secondary outcomes were operating time, lymph node retrieval, the volume of blood loss, complication prevalence, chest drain duration, postoperative length of stay and 30-day mortality.

Harvested data were divided into 2 groups: patients who underwent the uniportal approach were included in the u-VATS group; patients who underwent 3-portal lobectomy were included in the 3-portal VATS group.

Description of the techniques

Three-portal VATS in the standardized anterior approach, described from the Copenhagen group, surgeon and assistant usually operate on the same side of the table, facing the patient. The first step is a 4- to 5-cm anterior incision, without rib spreading, positioned between the breast and the lower angle of the scapula, usually in the fourth intercostal space, just anterior to the latissimus dorsi muscle. After thoracoscopic evaluation, a low anterior 1- to 1.5-cm camera port is positioned anteriorly to the hilum, at the level of the diaphragm. The third 1.5-cm incision is made further posteriorly in a straight line down from the scapula. Some surgeons use the same intercostal space for the 2 ports, to reduce traumatism to different spaces. The 30° angled camera is usually inserted in the lower port [8].

When performing uniportal VATS, the first operator stands in front of the patient, whereas the assistant can either stand in front of or alongside the surgeon, depending on one’s preference and from the type of lobectomy to be performed. A single incision up to 6 cm is made in the fourth to sixth intercostal space, between the mid and anterior axillary line, without retractors; some surgeons are used to a more anterior approach, where intercostal space is wider. The camera is usually held in the posterior part of the incision [9].

In the case of both techniques, lobectomy can be performed with a ‘hilum first’ or ‘fissure first’ approach, depending on the surgeons’ preference. In both cases, hilar structures are individually dissected, and a standard lymphadenectomy, as in open surgery, is mandatory.

Each enrolling centre independently has chosen intraoperative and postoperative analgesic strategies.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as the median and the interquartile range or the mean and the standard deviation. Categorical variables are shown as frequencies and percentages. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test or χ2 test was used as appropriate. Confidence intervals (CIs) were at 95% and 2-sided P-values were calculated. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. NRS was measured on a postoperative day (POD) 1, POD2, POD3 and on discharge day. Before analysis, the intensity of pain was dichotomized: (NRS) ≤3 described mild pain; whereas NRS score >3 described moderate/severe pain [17, 18]. NRS repeated measure data were analysed using ‘mean response profile’ method through generalized estimating equations (GEE) by employing time as a categorical variable, logit link function for linear predictor, a sandwich estimator for standard errors and unstructured working correlation matrix, selected by correlation information criterion. Repeated measurement design of participants' responses involves correlation within each participant. Correct inferences can only be obtained by taking into account this within-participant correlation between repeated measurements: GEE is the 1 statistical approach for analysing correlated data. Furthermore, GEE accounts also for the multicentre nature of the study.

We choose GEE because it allows a population-averaged interpretation of the regression coefficients [19]. The null hypothesis is that the difference of relative frequencies between the 2 surgical techniques is constant over time. This was tested using the multivariate Wald test, testing time (POD) × group interaction in the GEE regression model. Profile likelihood CIs were computed and univariate Wald test for each GEE-estimated parameter was used.

To reduce the impact of selection bias we used the propensity score (PS). The PS is defined as the conditional probability of assignment to a treatment, given a vector of particularly observed covariates; it is designed to mimic some of the particular characteristics of a randomized clinical trial within the context of an observational study. As appropriate and with caution, PS analysis allows an estimation of relative risk in binary outcomes [20]. We computed a PS for individual patients with logistic regression using demographic and clinical variables and evaluated the interaction among all preoperative covariates and square terms without time-dependent variables. The variables included into PS were all the preoperative patients’ characteristics reported in Table 1, including the conversion rate and epidural catheter, intercostal block, elastomeric pump and pericostal catheter. The generalized additive model was used to check the linear assumption on the logit scale in the PS model. Technically, PS becomes an additive covariate into the linear predictor of the GEE regression model, using natural cubic splines.

Table 1:

Preoperative patients’ characteristics

| Variables | Uniportal group (n = 172) | Three-portal group (n = 1808) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), n (%) | 89 (59.7) | 989 (54.7) | 0.507 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 69.5 (11.3) | 68.0 (12.0) | 0.002 |

| Charlson index, median (IQR) | 4 (3) | 4 (2) | <0.001 |

| FEV1%, median (IQR) | 92.0 (25.9) | 96.0 (27) | 0.161 |

| Tiffeneau, median (IQR) | 75.6 (15.5) | 76.7 (13.0) | 0.081 |

| COPD, n (%) | 20 (11.6) | 310 (17.1) | 0.080 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 27 (13.0) | 203 (11.2) | 0.623 |

| Coronary disease, n (%) | 14 (8.1) | 159 (9.0) | 0.881 |

| ECOG score, median (IQR) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.111 |

| CT scan T dimension (cm), n (%) | |||

| <2 | 87 (50.6) | 951 (52.4) | 0.669 |

| 2–3 | 53 (30.8) | 521 (28.7) | 0.643 |

| 3–5 | 31 (18.0) | 298 (16.4) | 0.681 |

| 5–7 | 1 (0.6) | 37 (2.0) | 0.295 |

| >7 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.05) | 0.999 |

| Clinical nodal involvement, n (%) | 14 (8.1) | 86 (4.8) | 0.079 |

| PET scan SUV, median (IQR) | 4 (5) | 3 (7) | 0.024 |

| Right side, n (%) | 110 (64.0) | 1123 (62.1) | 0.694 |

| Lobectomy types, n (%) | |||

| Right upper lobectomy | 60 (34.8) | 632 (34.9) | 0.999 |

| Right middle lobectomy | 8 (4.7) | 157 (8.7) | 0.092 |

| Right lower lobe | 37 (21.4) | 318 (17.6) | 0.238 |

| Upper bilobectomy | 5 (3.0) | 9 (0.5) | 0.001 |

| Lower bilobectomy | 0 (0) | 7 (0.4) | 0.885 |

| Left upper lobectomy | 29 (16.9) | 378 (20.9) | 0.248 |

| Left lower lobectomy | 33 (19.2) | 307 (17.0) | 0.531 |

| Adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 128 (74.5) | 1330 (73.6) | 0.878 |

| Squamocellular carcinoma, n (%) | 19 (11.0) | 228 (12.6) | 0.637 |

| Other histology, n (%) | 25 (14.5) | 250 (13.8) | 0.888 |

| Epidural catheter, n (%) | 11 (6.4) | 475 (26.3) | <0.001 |

| Intercostal block, n (%) | 148 (86) | 932 (51.5) | <0.001 |

| Elastomeric pump, n (%) | 34 (19.8) | 684 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| Pericostal catheter, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 104 (5.7) | 0.002 |

CT: computed tomography; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ; ECOG: eastern cooperative oncology group; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; IQR: interquartile range; PET: positron emission tomography; SUV: standardized uptake value.

We established a 1.5 clinical effect-size threshold for the odds ratio (OR), a value that is compatible with clinical experience and published indices. We also performed additionally 1:1 PS matching analysis using the nearest neighbour algorithm without replacing with a caliper of 0.2. All analyses were carried out using the R software package version 3.2.2.

RESULTS

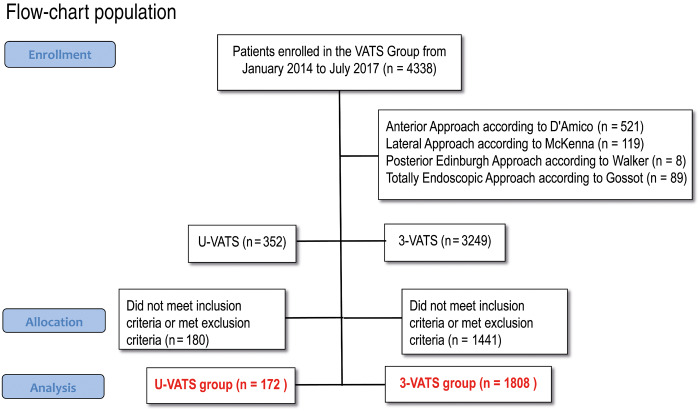

Forty-nine Italian thoracic surgery units were actively enrolling their patients in the Italian VATS Group Database at data extraction date. Among 4338 patients enrolled from January 2014 to July 2017, 1980 met the inclusion criteria, whereas 2358 were excluded from the analysis. Three hundred and twenty-three patients were excluded due to conversion to other techniques; the conversion rate in the 3-portal and in the uniportal approach were 9.9% and 8.0%, respectively. Finally, 1808 patients underwent 3-portal lobectomy and were included in the 3-portal VATS group, 172 received uniportal surgery and were included in the u-VATS group.

Table 1 reports demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample. The 2 groups were homogenous except for age, Charlson index, positron emission tomography standard uptake value of the lung nodule, type of lobectomy and postoperative pain relief devices (Fig. 1).

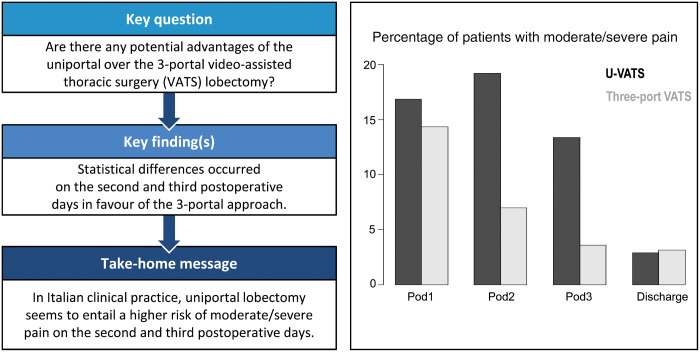

Figure 1:

Percentage of patients with moderate/severe pain. u-VATS: uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery; VATS: video-assisted thoracic surgery.

The unadjusted GEE regression model showed that pain decreased over time in the 2 groups (P < 0.001). There was a statistical difference in pain over time between the 2 groups (P < 0.001); in particular, there was no difference on POD1 (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.90–1.74; P = 0.170) and on discharge day (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.27–1.49; P = 0.310), whereas there was a difference on POD2 and POD3, in favour of 3-portal VATS. The u-VATS group had a higher risk of pain (NRS > 3) on second and third PODs (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.76–3.45; P < 0.001; OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.89–4.16; P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Mean postoperative NRS

| Group | POD1 | POD2 | POD3 | Discharge day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-VATS, mean NRS (SD) | 3.2 (1.9) | 3.3 (2.1) | 2.4 (1.8) | 1.4 (1.1) |

| Three-port VATS, mean NRS (SD) | 3.1 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.2) |

NRS: numeric rating scale; POD: postoperative day; SD: standard deviation; U-VATS: uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery.

The adjusted GEE regression model using PS showed closer results; pain decreased over time in the 2 groups (P < 0.001). There was a statistical difference in pain over time between the 2 groups (P < 0.001). There were no differences on POD1 (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.83–1.62; P = 0.401) and on discharge day (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.26–1.37; P = 0.219). On the second and third PODs, differences in favour of 3-portal VATS were still evident: OR 2.28, 95% CI 1.62–3.21; P < 0.001; OR 2.58, 95% CI 1.74–3.83; P < 0.001, respectively. NRS categorized values over time are reported graphically in Fig. 1. The PS matching based on 172 patients from each group yielded similar results with slightly wider CI, compared to PS adjusted regression analysis (POD1: OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.74–1.83; P = 0.494; POD2: OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.38–3.92; P < 0.001; POD3 OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.29–3.98; P = 0.01; discharge day: OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.23–1.89; P = 0.043). The absolute standardized mean differences between baseline covariates after matching, ranges from 0.012 to 0.13, indicating sufficient covariate balance.

Table 3 reports that intraoperative, pathological and clinical results were observed as secondary end points. The majority of variables resulted congruent in the 2 groups, yet the u-VATS had higher operative time (P < 0.001); conversely, this group had shorter chest drain permanence (P < 0.001) and length of stay (P < 0.001). No mortality was observed in both groups.

Table 3:

Intraoperative and postoperative clinical data

| Variables | Uniportal group (n = 172) | Three-portal group (n = 1808) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating time (min), median (IQR) | 195 (71) | 170 (70) | <0.001 |

| Volume of intraoperative blood loss (ml), median (IQR) | 100 (78) | 100 (75) | 0.312 |

| Number of dissected lymph nodes, median (IQR) | 12 (8) | 12 (8) | 0.504 |

| Pathological N+, n (%) | 14 (8.1) | 216 (11.9) | 0.172 |

| Two chest drains, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 399 (22.1) | <0.001 |

| Chest drain permanence (days), median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.3) | 4.0 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative hospitalization, median (IQR) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) | <0.001 |

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Haemothorax | 2 (1.2) | 19 (1.1) | 0.991 |

| Prolonged air leakage>7 days | 11 (6.4) | 126 (7.0) | 0.921 |

| Atelectasis | 2 (1.2) | 31 (1.7) | 0.834 |

| Pneumonia | 4 (2.3) | 50 (2.8) | 0.903 |

| Phrenic nerve injury/palsy | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.2) | 0.801 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy/dysphonia | 3 (1.7) | 8 (0.4) | 0.101 |

| Reintubation | 1 (0.6) | 5 (0.3) | 0.999 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | NS |

| TIA and stroke | 0 (0) | 3 (0.2) | 0.923 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9 (15.2) | 117 (6.5) | 0.654 |

| Renal | 0 (0) | 4 (0.2) | 0.999 |

| Chylothorax | 2 (1.2) | 7 (0.4) | 0.463 |

IQR: interquartile range; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

DISCUSSION

A considerable number of case series on uniportal VATS is available in the scientific literature; essentially, these papers support the fact that uniportal VATS lobectomy is possible and reasonably safe [21–24]. On the contrary, contrasting results are reported by studies comparing the 3-portal versus the uniportal approach to VATS lobectomy. To the present date, there is only a single monocentric randomized study comparing the uniportal with the ‘multiports’ VATS lobectomy; such a trial did not reveal statistically significant differences in terms of postoperative pain and median morphine use between the 2 groups [25]. The trial has been properly conducted but, unfortunately, the sample size was rather under-dimensioned, mainly because ‘multiports’ group (55 patients) included 2 different procedures: the Duke 2-port technique and the Copenhagen 3-portal approach. Considering that the number of ports could potentially affect pain perception, increasing the sample size would have proved correct.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis, which included the original uniportal proponent among the authors, collected 8 papers published between 2014 and 2016 [26]. The 8 studies, all from Asian centres, analysed retrospectively uniportal versus ‘multiportal’ VATS lobectomy; 78 was the average number of patients enrolled in uniportal arms and 153 in ‘multiportal’ arms. ‘Multiportal’ VATS lobectomy included a 3-ports procedure (4 papers), 2 and 3 ports procedures (2 papers), 3- and 4-ports procedure (1 paper) and an unknown number of ports (1 paper). The authors found no significant differences between uniportal versus ‘multiportal’ VATS in operative time, perioperative blood loss and rate of conversion to open surgery; patients who underwent a uniportal approach showed a statistically significant reduction in the duration of postoperative drainage, in length of hospital stay and in morbidity. It was disappointing to observe that such advantages in choosing the uniportal approach disappeared after a propensity match analysis. Recently, an observational study by Louis comparing multiport to uniportal VATS, reported a significant decrease in postoperative narcotic consumption in the uniportal group [27]. This is the first study that demonstrates lower analgesic consumption in a Western country; nevertheless, researchers at University of Kansas Hospital analysed their retrospective cohort in a peculiar way; in other words, patients who underwent a procedure with the uniportal technique and required additional ports were included in the ‘multiportal’ group.

Despite its weak scientific validation, uniportal VATS lobectomy constitutes an exciting technical development in thoracic surgery and exerts an extraordinary magnetism on young surgeons. The uniportal approach is having a large diffusion, even though its penetration in Western countries is still limited. The peculiar characteristics of the uniportal approach prompted the authors to compare this technique to the more widespread 3-portal VATS lobectomy in Italy. The 2-portal approach and other less common techniques were excluded from the data collection to minimize a potential bias; for the same reason, we limited the analysis to patients free from comorbidities, such as connective tissue disease or severe diabetes. In addition, we limited the data extraction to patients with no potentially critical local situation, such as previous thoracic surgery or cancer infiltrating the thoracic wall. Patients converted to other techniques were also excluded from the analysis. Finally, we obtained from the Italian VATS Group database a data set consisting of 1980 patients who underwent VATS lobectomy for clinical stage I–II NSCLC; these patients presumably constitute a population with reasonably homogeneous characteristics.

Our adjusted for PS and not adjusted analyses showed that the intensity of pain reported by patients decreased over time; at discharge, only ∼3% of them had moderate or severe pain. The trend of pain was different in the 2 groups; namely, the probability to have moderate or severe pain in POD2 and POD3 was double for patients who underwent uniportal lobectomy versus patients who had 3-portal lobectomy (POD2: OR = 2.28; POD3: OR = 2.58). We are aware that our results diverge from current literature; however, this is the largest observational study focussed on uniportal versus 3-portal VATS lobectomy, and its national scope allows a better insight into actual clinical practice. A simple explanation of major pain in the uniportal approach could be the crowding of the scope and instruments in a single incision; despite experienced surgeons could limit this problem, such congestion probably leads to heavier pressure on the thoracic wall than in manoeuvres performed through 3 ports.

In our study, the uniportal approach appears technically more demanding than the 3-portal technique, considering the longer operative time; notwithstanding, the number of dissected lymph nodes and the volume of intraoperative blood loss were similar. These last results support the idea that the procedure is feasible and safe. Complication prevalence was similar, and no mortality was observed in both groups. The postoperative length of stay was statistically lower in the uniportal group. The faster discharge could be the result of several factors; differences in patient management in some centres could be one of those factors.

Another reason for faster discharge in the uniportal group could be related to chest tube management: a considerable percentage of patients (22%) in the 3-portal group had 2 chest drains, whereas the great majority of patients in the uniportal group had a single drainage. Given that there are no reasons to use 2 drainages, it is an established practice to remove the chest tubes on consecutive days; this behaviour impacts the length of the hospital stay.

Limitations

This study presents a series of limitations; first of all, the postoperative consumption of analgesics was not indicated in the database, and therefore, to indicate the pain parameter as the main outcome we had to rely on the NRS, an extremely subjective indicator. Moreover, the analgesic strategy was independently chosen by each enrolling centre. In addition, as all retrospective observational analyses, our study presents intrinsic sources of bias and confounding by indication. Selection bias in the recruitment probably shows in our study; we are aware that a number of thoracic units did not join the Italian VATS Group; consequently, our population, although highly representative, cannot be considered a true ‘national sample’. Information bias, consisting of measurement errors and misclassifications, was possible. A confounding risk could also be present in the current study. A risk factor for the main outcome, which is associated with the procedures but is not recorded, leads to a biased evaluation of the investigated risk factors: this is the case of surgeons’ individual experience, which was not recorded in the original VATS Group database (now present in the second database version). Simpson’s paradox may arise when data are evaluated in groups, but there is an uneven distribution of an important parameter within the groups. In the current study, pain relieving techniques were highly unbalanced in the 2 groups and we had to rely on the adjusted statistical models.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the investigation of the Italian VATS Group database, which collected 4338 procedures in 43 months, allowed the selection of 1980 VATS lobectomy performed with the 3-portal or uniportal approach. In this selected cohort, offering an insight into the current clinical practice in Italy, patients who underwent uniportal VATS lobectomy seem to present a double risk of moderate to severe pain on the second and third PODs. In our opinion, the uncritical adoption of the uniportal technique does not guarantee a pain reduction in the immediate postoperative course; therefore, a comprehensive vision of the analgesic treatment is fundamental.

Acknowledgement

Collaborators of the Italian VATS Group: Mancuso M. – Pernazza F. (Alessandria Hospital), Refai M. (Ancona Hospital), Bortolotti L. – Rizzardi G. (Humanitas Gavazzeni, Bergamo), Gargiulo G. – Dolci GP. (S. Orsola Hospital, Bologna), Perkmann R. – Zaraca F. (Bolzano Hospital), Benvenuti M. – Gavezzoli D. (Brescia Hospital), Cherchi R. – Ferrari P. (Brotzu Hospital, Cagliari), Mucilli F. – Camplese P. (S. Maria Annunziata Hospital, Chieti), Melloni G. – Mazza F. (Cuneo Hospital), Cavallesco G. – Maniscalco P. (Ferrara University Hospital), Voltolini L. – Gonfiotti A. (Careggi Hospital, Firenze), Stella F. – Argnani D. (Morgagni Hospital, Forlì), Pariscenti GL – Iurilli (S. Martino Hospital, Genova), Surrente C. – Lopez C. (Fazzi Hospital, Lecce), Droghetti A. – Giovanardi M. (C. Poma Hospital, Mantova), Breda C. – Lo Giudice F. (Mestre Hospital), Alloisio M. – Bottoni E. (IRCCS Humanitas, Milano), Spaggiari L. – Gasparri R. (IEO Hospital, Milano), Torre M. – Rinaldo A. (Niguarda Hospital, Milano), Nosotti M. – Rosso L. (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Milano), Negri GP. – Bandiera A. (S. Raffaele Hospital, Milano), Stefani A. – Natali P. (Modena Hospital), Scarci M. – Pirondini E. (S. Gerardo Hospital, Monza), Curcio C. – Amore D. (Monaldi Hospital, Napoli), Baietto G. – Casadio C. (Maggiore della Carità Hospital, Novara), Nicotra S. – Dell’Amore A. (University Hospital Padova), Bertani A. – Russo E. (IRCCS ISMETT, Palermo), Ampollini L. – Carbognani P. (University Hospital, Parma), Puma F. – Vinci D. (University Hospital, Perugia), Andreetti C. – Poggi C. (S. Andrea Hospital, Roma), Cardillo G. (Forlanini Hospital, Roma), Margaritora S. – Meacci E. (Gemelli Hospital, Roma), Luzzi L. – Ghisalberti M. (University Hospital, Siena), Crisci R. – Zaccagna G. (Mazzini Hospital, Teramo), Lausi P. – Guerrera F. (Molinette Hospital, Torino), Fontana D. – Della Beffa V. (S. Giovanni Bosco Hospital, Torino), Morelli A. – Londero F. (S. Maria della Misericordia Hospital, Udine), Imperatori A. – Rotolo N. (Varese Hospital), Terzi A. – Viti A. (Negrar Hospital, Verona), Infante M. – Benato C. (Borgo Trento Hospital, Verona).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

APPENDIX. CONFERENCE DISCUSSION

Dr R. Petersen (Copenhagen, Denmark): VATS lobectomy has become the standard of care for the majority of thoracic surgical departments in Europe during the last decade. Since the initial report of uniportal VATS lobectomy in 2010, the approach has attracted a lot of attention. Today more than 200 studies are published on uniportal VATS lobectomy and the majority of these studies are case reports, editorials and ‘how to do it’ papers. Only very few comparative studies have been published and among them only 1 randomized study from Spain. Feasibility has definitely been demonstrated even with very advanced cases, such as double sleeve resections, but the evidence of superiority of the uniportal approach compared to a multiportal approach is missing. I think we must congratulate the Italian team for their effort to provide comparative data.

I have 3 questions: Is it fair to conclude that there is less pain in the uniportal group, when the pain management regimen was so different? About 26% of patients having a 3-portal approach had pain control using epidural analgesia and only 6% in the uniportal group. I know you tried to correct this with propensity score match, but I would like you to further elaborate on the differences.

Dr D. Tosi (Milan, Italy): We analysed both with the unmatched and matched results. The observation is correct because the analgesic devices can influence the postoperative outcomes. Moreover, I think the major limitation is the consumption of analgesics because we don’t know whether it was higher in 1 group than in the other. Our statistician, after adjusting the regression, said that we could optimize the results without having the bias of the epidural catheter. This is an important point to reflect on.

Dr Petersen: My second question is regarding the lengths of stay. It’s shorter in the uniportal group, 3 vs 4 days and it’s mainly explained by the shorter duration of chest drains in the uniportal group, which is 2 vs 3 days. But 22% of the patients in the 3-port groups had 2 chest drains versus only 0.6% in the uniportal group. Can you explain the reason for the different protocols among these centres?

Dr Tosi: I think that in a lot of centres the experience came from the open surgery and in the open surgery usually 2 drains are more common than 1. In the 2-portal group, the possibility of using 2 chest drains, maybe in some difficult cases, when you got a leakage at the end of the operation brings to this behaviour, whereas in the uniportal group, by definition 2 chest drains in 1 incision may be too much. It can be explained by the attitude of the particular centres so, if you perform uniportal VATS, you’ve got just 1 chest drain and you are in a hurry to discharge the patient early. In Italy you usually remove 1 chest drain and the other one on the following day; the next day you request a chest X-ray. I think this explains the difference in the length of stay.

Dr Petersen: The conversion rate in the 3-portal VATS group was only 0.1% in 1808 patients from 49 units and there was no 30-day mortality reported. Clearly, there must be an underrepresentation of conversions and maybe major complications. Can we trust this data to be reliable?

Dr Tosi: Regarding the complications, I think that complications after VATS procedures are recorded in the database and I’ve talked to the statistician of the VATS group database; the mortality really seemed to be zero. Regarding the converted procedures, those are one of the major limitations of our study because the database is voluntary. Of course, you’ve got the possibility to register the procedure as being converted, but in some cases converted procedures may not have been uploaded to the database.

Dr E. Pompeo (Rome, Italy): I think that despite the several biases, which can be found in the retrospective study like this, there are important issues to be noted. Firstly, in the uniportal approach postoperative pain was higher, following propensity score matching 2 or 3 days, postoperatively. This is important in my opinion because it introduced some ergonomical and methodological issues in this kind of approaches. First of all, the crowding of instruments through uniportal approaches is greater than through 3-port approaches, and this may also affect the postoperative pain and should be investigated in more detail. Secondly, the position of the tube is different, because through the uniportal approach you have to push the tube, making a curve inside the chest to allow draining all the chest areas and this, in my opinion, can also increase the postoperative pain. The problem does exist and this paper raised the question to be investigated more in detail.

Dr Tosi: It’s a correct observation. What I want to highlight is that this study’s aim is not to prove the superiority of 1 technique over the other. We have some biases, we know. This is really just a snapshot of the Italian clinical scenario. One of the hypotheses is that the crowding of the instruments in 1 incision can be more painful than 3 instruments in 3 trocars. Of course, we also have to think about the learning curve, because as you have seen, the operating time is longer in the uniportal group. Maybe in the next year, the difference between the techniques won’t be this big.

Dr H. V. Kara (Istanbul, Turkey): The number of lymph nodes excised is a good result. Would you comment on the preoperative mediastinal surgical staging for the groups that contribute patients to this study? Were all the patients evaluated with either mediastinoscopy or VAMLA before surgery? We all know that the number of the lymph nodes is effective according to the preoperative mediastinal staging. Did all those patients have preoperative mediastinal surgical staging, mediastinoscopy or VAMLA?

Dr Tosi: The number of lymph nodes is one of the most interesting results because both techniques had a similar number and with an adequate number of 15 lymph nodes each. The majority of patients did not undergo the mediastinoscopy before. We excluded the T3 disease, and those after induction therapy, so we included only stages I and II patients, therefore, very few underwent mediastinoscopy before.

Dr Kara: We all know that chest drain occupying the intercostal space is a major problem with pain. Regarding that 3-portal cases have 2 chest tubes, do you think it may cause a bias on the side of uniportal? The patient with 2 chest drains postoperatively will certainly have more pain than one with a single drain on the uniportal side. Can we conclude that uniportal is effective on the postoperative pain? Most of the patients on the 3-portal side have 2 drains, and when you pull out the drain, the pain dramatically decreases.

Dr Tosi: That’s correct, you have more pain because of the 2 drains. You can have more pain because the only drain is in the incision, so this is understandable. The results didn’t go in that direction so even patients with 2 chest drains had a lower level of pain.

Dr Kara: We can recommend you to make a subgroup analysis, regarding only the patients with a single chest tube.

Dr D. Gossot (Paris, France): I wonder whether this type of study is really relevant. A couple of years ago we had a breakthrough, switching from open to close chest surgery and now we have many studies comparing 1 port to 2 ports to 3 ports to 4 ports, with a huge amount of bias, as in your study. There are 49 centres; I doubt that all the surgeons of those 49 centres have the same definition of single-port and 3-port techniques. As you know, the pain varies very much according to the diameter of the instruments, the location of the ports, whether they are in front or in the back. For me, it’s almost impossible to analyse. The second point, I think the most important, is that in 90% of these patients, we are dealing with lung cancer, and I would prefer to have oncological results of all these techniques, rather than an analysis of whether the patients are staying 1 day more or 1 day less. I don’t think it’s a major issue.

Dr Tosi: Regarding your first point, I said those analyses won’t prove the 1 approach being better than the other. It’s just a snapshot of the Italian clinical reality now, so we don’t want to say that we have the possibility to compare the 2 techniques and definitively say, which one is better. The second point is very important and it’s in our conclusions. It’s important to offer the patient a safe procedure but most of all, one that is oncologically adequate. Both procedures meet these requirements.

Dr H. Hansen (Copenhagen, Denmark): I wonder about the low conversion rate. You only reported the conversion to open surgery. Were there conversions from uniportal surgery to multiport surgery and if they were, were they counted in the uniportal group or multiport group? Is it an intention to treat or not? Because if you have to convert from 1 port to several ports, there will likely be problems, and therefore, there will be patients in whom it affects the outcome.

Dr Tosi: We do not have the data on procedures converted from uniport to multiports.

Dr K. Naunheim (St. Louis, USA): I have to agree with Dr Gossot. One-port, 2-port, 3 port, 4 port, it’s becoming less and less pertinent and less important. Certainly, in the USA, I know now in Europe, these Enhanced Recovery After Thoracic Surgery programmes, which use multiple intercostal blocks, with long-acting liposomal anaesthetics, anti-inflammatory drugs, etc. The question of postoperative pain is becoming moot. Essentially nobody is using epidural catheters anymore. This is a retrospective study, I think, in 2 senses. First of all, it’s retrospective in that you’re looking back at the database but it’s also looking at an old issue and one that is going to become less and less pertinent. I think that the real prospective issue we ought to be looking at in the future has to do with minimally invasive surgery versus SBRT, Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. With the increasing utilization of lung cancer screening, we’re finding smaller and smaller lesions and at least in the USA, those patients are getting surgery less and less often. Not only because of the primary care physicians, but also because patients are choosing non-surgical methodologies. They do not want surgery; they want less and less invasive procedures. I think that as a society of thoracic surgeons, AATS, ESTS and all of us in the future need to be focussing our attention not on these issues, which though pertinent, are old and really will not affect our specialty or our patients in the future. We need to be concentrating on this issue of surgery versus non-surgical treatment with SBRT. I think that’s the place where we need to put most of our emphasis because that’s where we’re going to make a difference and really help our patient population.

Contributor Information

Italian VATS Group:

M Mancuso, F Pernazza, M Refai, L Bortolotti, G Rizzardi, G Gargiulo, G P Dolci, R Perkmann, F Zaraca, M Benvenuti, D Gavezzoli, R Cherchi, P Ferrari, F Mucilli, P Camplese, G Melloni, F Mazza, G Cavallesco, P Maniscalco, L Voltolini, A Gonfiotti, F Stella, D Argnani, G L Pariscenti, C Surrente, C Lopez, A Droghetti, M Giovanardi, C Breda, F Lo Giudice, M Alloisio, E Bottoni, L Spaggiari, R Gasparri, M Torre, A Rinaldo, M Nosotti, L Rosso, G P Negri, A Bandiera, A Stefani, P Natali, M Scarci, E Pirondini, C Curcio, D Amore, G Baietto, C Casadio, S Nicotra, A Dell’Amore, A Bertani, E Russo, L Ampollini, P Carbognani, F Puma, D Vinci, C Andreetti, C Poggi, G Cardillo, S Margaritora, E Meacci, L Luzzi, M Ghisalberti, R Crisci, G Zaccagna, P Lausi, F Guerrera, D Fontana, V Della Beffa, A Morelli, F Londero, A Imperatori, N Rotolo, A Terzi, A Viti, M Infante, and C Benato

Presented at the Brompton Session of the 26th European Conference on General Thoracic Surgery of the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 27–30 May 2018.

REFERENCES

- 1. Roviaro G, Rebuffat C, Varoli F, Vergani C, Mariani C, Maciocco M. Videoendoscopic pulmonary lobectomy for cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1992;2:244–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, Balekian AA, Murthy SC. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143(5 Suppl):e278S–313S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Detterbeck F. Thoracoscopic versus open lobectomy debate: the pro argument. Thorac Surg Sci 2009;6:Doc04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang R, Ferguson MK. Video-assisted versus open lobectomy in patients with compromised lung function: a literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124512.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zieliński M, Nabialek T, Pankowski J. Transcervical uniportal pulmonary lobectomy. J Vis Surg 2018;4:42.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hernandez-Arenas LA, Lin L, Yang Y, Liu M, Guido M, Gonzalez-Rivas D et al. Initial experience in uniportal subxiphoid video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for major lung resections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunning J, Elsaegh M, Nardini M, Gillaspie EA, Petersen RH, Hansen HJ et al. Microlobectomy: a novel form of endoscopic lobectomy. Innovations 2017;12:247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hansen HJ, Petersen RH. Video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy using a standardized three-port anterior approach—the Copenhagen experience. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2012;1:70–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gonzalez D, Paradela M, Garcia J, Dela Torre M. Single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg 2011;12:514–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gonzalez-Rivas D, Paradela M, Fernandez R, Delgado M, Fieira E, Mendez L et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: two years of experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McElnay PJ, Molyneux M, Krishnadas R, Batchelor TJ, West D, Casali G. Pain and recovery are comparable after either uniportal or multiport video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: an observation study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015;47:912–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang BY, Liu CY, Hsu PK, Shih CS, Liu CC. Single-incision versus multiple-incision thoracoscopic lobectomy and segmentectomy: a propensity-matched analysis. Ann Surg 2015;261:793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu Y, Liang M, Wu W, Zheng J, Zheng W, Guo Z et al. Preliminary results of single-port versus triple-port complete thoracoscopic lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:92.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu CC, Shih CS, Pennarun N, Cheng CT. Transition from a multiport technique to a single-port technique for lung cancer surgery: is lymph node dissection inferior using the single-port technique? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49(Suppl 1):64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shen Y, Wang H, Feng M, Xi Y, Tan L, Wang Q. Single- versus multipleport thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer: a propensity-matched study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49(Suppl 1):48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mu JW, Gao SG, Xue Q, Zhao J, Li N, Yang K et al. A matched comparison study of uniportal versus triportal thoracoscopic lobectomy and sublobectomy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Chin Med J 2015;128:2731–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mantha S, Thisted R, Foss J, Ellis JE, Roizen MF. A proposal to use confidence intervals for visual analog scale data for pain measurement to determine clinical significance. Anesth Analg 1993;77:1041–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bendixen M, Jørgensen OD, Kronborg C, Andersen C, Licht PB. Postoperative pain and quality of life after lobectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or anterolateral thoracotomy for early stage lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH, Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Hoboken: Wiley, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirai K, Takeuchi S, Usuda J. Single-incision thoracoscopic surgery and conventional video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a retrospective comparative study of perioperative clinical outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49(Suppl 1):i37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang L, Liu D, Lu J, Zhang S, Yang X. The feasibility and advantage of uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) in pulmonary lobectomy. BMC Cancer 2017;17:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ji C, Xiang Y, Pagliarulo V, Lee J, Sihoe ADL, Kim H et al. A multi-center retrospective study of single-port versus multi-port video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy and anatomic segmentectomy. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:3711–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Young R, McElnay P, Leslie R, West D. Is uniport thoracoscopic surgery less painful than multiple port approaches? Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg 2015;20:409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perna V, Carvajal AF, Torrecilla JA, Gigirey O. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy versus other video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy techniques: a randomized study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:411–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris CG, James RS, Tian DH, Yan TD, Doyle MP, Gonzalez-Rivas D et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of uniportal versus multiportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2016;5:76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Louis SG, Gibson WJ, King CL, Veeramachaneni NK. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) technique is associated with decreased narcotic usage over traditional VATS lobectomy. J Vis Surg 2017;3:117.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]