Abstract

Objectives

Candida auris is an emerging, often MDR, yeast pathogen. Efficient animal models are needed to study its pathogenicity and treatment. Therefore, we developed a C. auris fruit fly infection model.

Methods

TollI-RXA/Tollr632 female flies were infected with 10 different C. auris strains from the CDC Antimicrobial Resistance bank panel. We used three clinical Candida albicans strains as controls. For drug protection assays, fly survival was assessed along with measurement of fungal burden (cfu/g tissue) and histopathology in C. auris-infected flies fed with fluconazole- or posaconazole-containing food.

Results

Despite slower in vitro growth, all 10 C. auris isolates caused significantly greater mortality than C. albicans in infected flies, with >80% of C. auris-infected flies dying by day 7 post-infection (versus 67% with C. albicans, P < 0.001–0.005). Comparison of C. auris isolates from different geographical clades revealed more rapid in vitro growth of South American isolates and greater virulence in infected flies, whereas the aggregative capacity of C. auris strains had minimal impact on their growth and pathogenicity. Survival protection and decreased fungal burden of fluconazole- or posaconazole-fed flies infected with two C. auris strains were in line with the isolates’ disparate in vitro azole susceptibility. High reproducibility of survival curves for both non-treated and antifungal-treated infected flies was seen, with coefficients of variation of 0.00–0.31 for 7 day mortality.

Conclusions

Toll-deficient flies could provide a fast, reliable and inexpensive model to study pathogenesis and drug activity in C. auris candidiasis.

Introduction

Candida auris is an emerging ascomycete yeast pathogen first described in 2009.1–4 Since then its prevalence has been rapidly growing, with cases of invasive disease and outbreaks in several parts of the globe. At least four distinct geographic clades have been identified by genotypic analyses.4C. auris represents a unique threat owing to its frequent MDR, invasive potential in critically ill patients and difficult eradication from hospital environments.2–4 The reasons for the simultaneous and independent emergence of C. auris on several continents and the frequent resistance to antifungals have not been fully investigated yet.2–6

Though the understanding of C. auris pathogenicity is in its early stages, a number of virulence factors have been reported including strain-dependent phospholipase activity, proteinase secretion and biofilm formation, enhanced tolerance to oxidative and heat stress compared with Candida albicans and strong persistence on plastic surfaces.6–9 Importantly, considerable genetic variability and phenotypic plasticity were described among isolates from different geographic regions.1,5 Experimental in vivo data on the virulence of C. auris are based on a very limited selection of isolates,10–12 and comparative pathogenicity screens of the geographical clades are lacking. Studies of drug efficacy against C. auris relied on conventional animal models that are laborious and costly.13

To that end, we evaluated C. auris infection and treatment in a Toll-deficient Drosophila melanogaster fly model, previously described to be of value for the dissection of C. albicans pathogenicity and extensively validated for a range of medically relevant mould and yeast pathogens.14,15 We demonstrate significantly enhanced virulence of 10 disparate clinical C. auris isolates compared with C. albicans, and provide proof-of-principle experiments for azole treatment of C. auris-infected Toll-deficient D. melanogaster flies.

Materials and methods

Isolates

The C. auris panel (AR381–AR390) was obtained from the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance (AR) Isolate Bank (kind gift of S. Lockhart and T. Chiller). Information on azole MICs was provided by the CDC AR bank online portal (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/ARIsolateBank/Panel/PanelDetail? ID=2). The aggregation phenotypes and geographical clades of these strains have been previously described, and are summarized in Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).7,16 Clinical C. albicans strains (internal numbers 2516, 7892 and 8910) isolated from patients at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center were used for comparison. We used isolates with different storage periods. Two out of the three C. albicans isolates (7892 and 8910) were sourced in 2018; the third (2516) had been cryopreserved in 2003. All Candida strains were grown and maintained on yeast–peptone–dextrose (YPD) agar.

In vitro growth assay

A single colony of each Candida isolate was grown overnight at 35°C and 200 rpm in YPD liquid. A total of 106 yeast cells were inoculated in 5 mL of YPD medium and incubated for another 4 h at 35°C and 200 rpm to mid log phase. Subsequently, yeast cells were washed twice in sterile saline, thoroughly vortexed at high speed, counted with a haemocytometer and suspended in yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/mL. A 100 μL aliquot of each yeast suspension was dispensed in 96-well plates; plain YNB medium was used for control wells. The plates were placed in a plate reader (Powerwave HT, Bio-Tek Instruments) at 37°C for 48 h and agitated before each measurement. Turbidity was measured at 690 nm every 6 h in triplicate. In parallel, 5 mL of each yeast cell solution (5 × 104 yeast cells) were kept in 50 mL tubes at 37°C and cell concentrations were determined microscopically after 24 and 48 h using a haemocytometer.

Infection of Tl-deficient D. melanogaster flies

Tlr632/TlI-RXA Drosophila mutant flies were generated by crossing flies carrying a thermosensitive allele of Toll (Tlr632) with null allele of Toll (TlI-RXA) flies. We used standard procedures for the manipulation, housing and feeding of Drosophila flies as previously described.14 The dorsal side of the thorax of CO2-anaesthetized female flies (7–14 days old) was pricked with a thin needle dipped in 1 × 108/mL Candida solutions.14 Flies were kept at 29°C and transferred into fresh vials every 2 days. Survival was assessed daily until day 7 after infection. Three independent experiments were performed on different days. To decrease the influence of circadian rhythm, all experiments were performed in the afternoon.

Antifungal treatment of flies

Tl-deficient flies were starved for 8 h and subsequently transferred to vials containing regular fly food or fly food supplemented with 1 mg/mL fluconazole or posaconazole as previously described.14 Flies were allowed to feed for 24 h before being inoculated with C. auris as described above.

Determination of fungal burden

Dead flies were collected daily and stored at −80°C. On day 7 post-infection, the remaining flies were euthanized and combined with the previously dead (frozen) flies. All samples (23–27 flies in total per cohort) were weighed, suspended in 1 mL of PBS and homogenized using a bead beater (Biospec Products). A 10 μL aliquot of the homogenate was added to 990 μL of PBS. The mixture was thoroughly vortexed and 100 μL was plated on YPD agar plates. Colonies were counted after 24 h. The following formula was used to determine the amount of cfu per gram of tissue: (number of colonies/mL plated × dilution factor)/[tissue (g)/mL original homogenate].

Histopathology

Dead flies were fixed in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections of representative flies were stained with Grocott–Gomori methenamine-silver nitrate (GMS), examined for visible fungal burden under a light microscope and photo-documented using a ScanScope slide scanner (Aperio, Leica Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.03. Survival curves were compared using the log rank test. In vitro growth rates and fungal burden were compared using the paired or unpaired two-sided t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test, depending on the experiment setup. Significant P values are indicated by asterisks in the figures: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Results

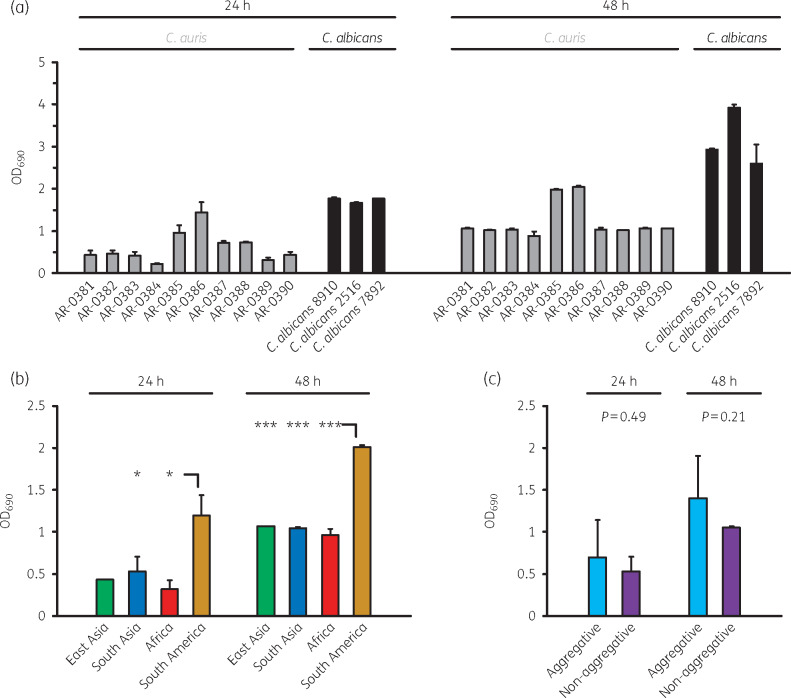

First, we compared in vitro growth of the 10 C. auris CDC AR bank isolates with 3 clinical C. albicans strains using a turbidity-based assay. All tested C. auris isolates exhibited considerably slower in vitro growth, with an OD690 of 0.22–1.44 (C. auris) versus 1.67–1.78 (C. albicans, P < 0.001) after 24 h, and 0.89–2.04 (C. auris) versus 2.60–3.92 (C. albicans, P < 0.001) after 48 h (Figure 1a). The turbidity assay was validated by manual (microscopic) determination of yeast cell concentrations, confirming significantly lower yeast cell concentrations for C. auris after 24 h (0.50–1.63 × 108/mL versus 2.50–3.13 × 108/mL, P < 0.001) and 48 h (1.25–3.25 × 108/mL versus 3.50–6.25 × 108/mL, P = 0.002), respectively (Figure S1a). High correlation between both readouts was seen, with Pearson coefficients of 0.93 and 0.94 (24 h/48 h) considering all isolates, and 0.84/0.81 for the 10 C. auris isolates only. Isolates from the same geographic clades showed comparable turbidity and yeast cell concentrations, with significantly more rapid in vitro growth of the two strains of South American origin (AR-0385 and AR-0386, Figure 1b and Figure S1b). No significant difference in turbidity or yeast cell concentrations was observed between aggregative and non-aggregative C. auris isolates (Figure 1c and Figure S1c).

Figure 1.

Comparative assessment of in vitro growth of 10 C. auris and 3 C. albicans isolates. (a) In vitro growth of C. auris AR-0381–AR-0390 and three clinical C. albicans isolates was assessed by turbidity measurement as described in the Materials and methods section. Mean OD690 values based on three replicates (+SD) after 24 and 48 h of incubation are provided. (b) Comparison of OD690 values depending on the geographical clade of the 10 C. auris isolates. One East Asian, five South Asian, two African and two South American isolates (Table S1) were assessed. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used for significance testing. (c) OD690 values of five non-aggregating and five aggregating C. auris isolates (Table S1) were compared. The unpaired, two-sided t-test was used for significance testing. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

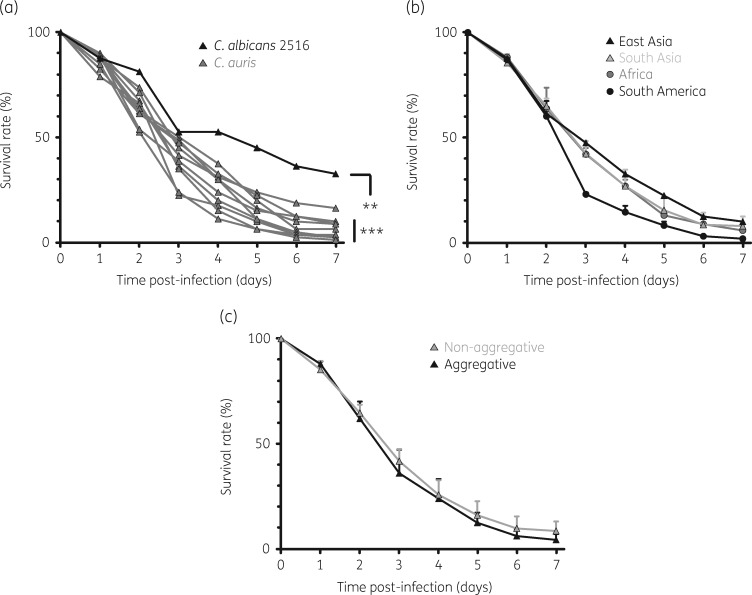

Next, we tested the in vivo virulence of the AR bank panel C. auris strains versus C. albicans 2516 in Tl-deficient D. melanogaster flies. Animals infected with C. albicans 2516 exhibited a median survival time (MST) of 5 days and a 33% 7 day survival rate (Figure 2a). For C. auris-infected flies, the MST was significantly shortened (3–3.5 days) and 7 day post-infection mortality was higher (≥84%) for all AR bank strains tested (hazard ratio 1.56–2.38, P < 0.001–0.005). Along with more rapid in vitro growth, both South American C. auris isolates tested caused greater 3 day mortality in the fly model than isolates from other geographic clades (survival rates 23%–24% versus 35%–50%, P < 0.001, Figure 2b). The aggregative phenotype of the isolates did not significantly influence the survival rates of infected flies (Figure 2c). Considering all 10 C. auris isolates studied, 24 h in vitro growth rates (yeast cell counts) significantly correlated with 3 day mortality in flies (r = 0.91, P < 0.001) and to a lesser extent with 7 day mortality (r = 0.55, P = 0.10).

Figure 2.

Survival rates of D. melanogaster flies infected with C. albicans 2516 and 10 C. auris AR bank isolates. (a) Survival rates of Tl-deficient D. melanogaster flies infected with C. albicans 2516 (black) versus C. auris AR-0381–AR-0390 (grey) were monitored for 7 days post-infection. Cumulative results from three independent experiments with a total of 80 flies per cohort are shown. The log rank test was used for significance testing. (b and c) Mean survival rates were compared depending on the geographic origin (b) and aggregative capacity (c) of the isolates. Mean survival rates (triangles/circles) and standard deviations are shown. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

To confirm increased mortality of C. auris- versus C. albicans-infected flies, we performed an independent experiment comparing C. auris strain AR-0381, the rather slow-growing and less virulent South Asian strain, with three clinical C. albicans isolates (Figure S2). Infection with all three C. albicans strains was associated with a longer MST (5–6 days versus 4 days) and higher 7 day survival rates (24%–46% versus 11%, P < 0.001–0.01), corroborating our previous findings. Importantly, we verified that the greater virulence of C. auris is not due to differences in the inoculum delivered by needle pricking (Figure S3).

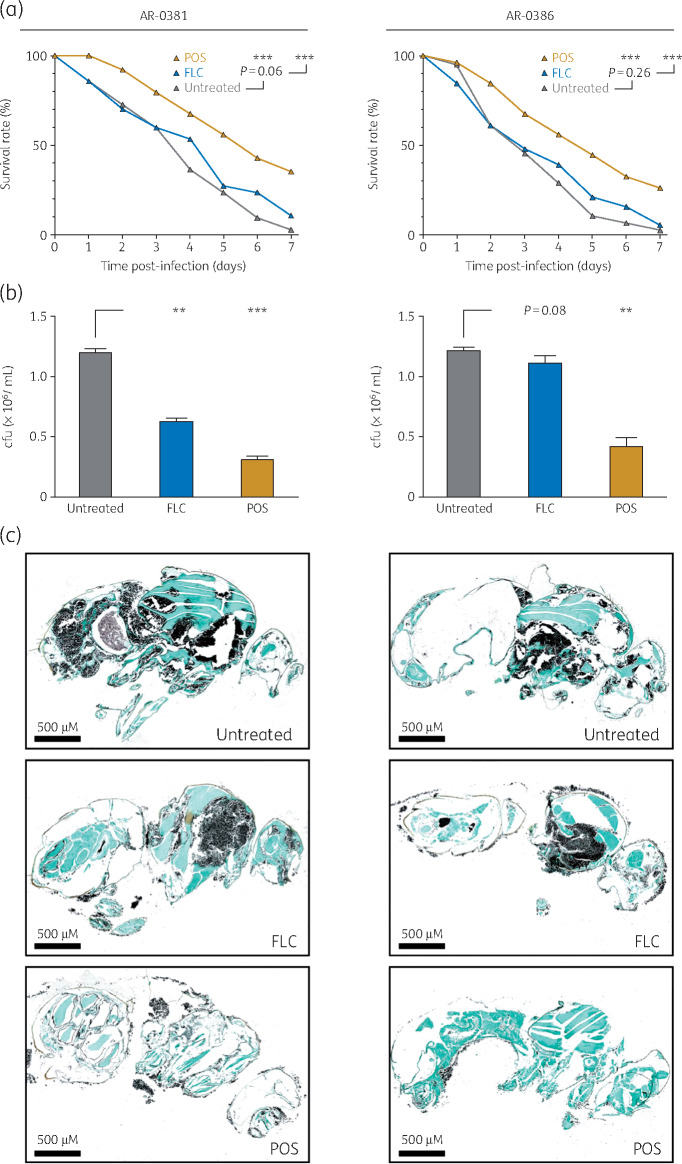

We next evaluated the suitability and reproducibility of the D. melanogaster model to study antifungal treatment of C. auris. For this, C. auris strains AR-0381 and AR-0386 were selected owing to their disparate in vitro azole susceptibility (MIC of fluconazole, AR-0381 4 mg/L, AR-0386 >256 mg/L; MIC of posaconazole, AR-0381 0.06 mg/L, AR-0386 0.5 mg/L). AR-0386 caused a more rapid decline in survival rates in untreated infected flies than AR-0381 (Figure 3a). Although fluconazole treatment decreased the fungal burden in AR-0381-infected flies by approximately half (P = 0.004, Figure 3b) and prolonged the MST from 4 to 5 days, the overall survival benefit did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06). In line with in vitro resistance, neither fungal burden nor 7 day mortality was significantly reduced by fluconazole treatment of AR-0386-infected flies and the MST remained unaltered (3 days). For both C. auris strains tested, posaconazole treatment led to prolonged MST (6 days for AR-0381 and 5 days for AR-0386) and significantly improved overall survival (P < 0.001). Similarly, fungal burden, assessed by cfu quantification (Figure 3b) and GMS staining of histopathological sections (Figure 3c), was reduced in posaconazole-treated flies.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of azole treatment in C. auris-infected D. melanogaster flies. (a) Survival rates of Tl-deficient D. melanogaster flies infected with C. auris AR-0381 or AR-0386 and fed with plain or azole-supplemented (FLC, fluconazole; POS, posaconazole) fly food were monitored for 7 days post-infection. Cumulative results from three independent experiments with a total of 77 flies per cohort are shown. The log rank test was used for significance testing. (b) The fungal burden of C. auris AR-0381- or AR-0386-infected flies depending on azole supplementation of fly food was determined in three independent experiments. Mean cfu counts and standard deviations are shown. The two-sided paired t-test was used for significance testing. (c) Histopathological sections of flies dying on day 5 to 7 post-infection were stained with GMS. Representative images are provided. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Analysing the technical reproducibility of survival curves, coefficients of variation (CVs) ranged from 0.11 to 0.55 and from 0.00 to 0.31 for 3 and 7 day survival rates for non-treated and antifungal-treated flies, respectively (data not shown). Even lower CVs were achieved for cfu quantification (0.03–0.19, Figure 3b), indicating high reproducibility of C. auris infection and antifungal treatment response in the D. melanogaster fly model.

Discussion

Candida auris is an emerging, often MDR pathogen causing significant mortality and incremental cost burden in critically ill patients. Efficient animal models are warranted to obtain a better understanding of its pathogenicity and screen for new antifungal treatment options. Tl-deficient flies have been successfully employed as an efficient invertebrate model for yeast infections.14 As different virulence patterns compared with other medically important yeasts including C. albicans were reported,10–12 we assessed the feasibility and reproducibility of C. auris infection in the Drosophila model.

Despite slower in vitro growth compared with C. albicans, consistently greater mortality of C. auris-infected flies was observed for all isolates tested, with considerable correlation of in vitro growth and survival rates among the 10 C. auris isolates. From a technical perspective, we found high reproducibility of survival rates, MSTs and fungal burden in C. auris-infected flies. Moreover, the magnitude of protection by azole treatment in our model correlated with the degree of in vitro susceptibility in two C. auris isolates displaying divergent azole susceptibility.

We used the FDA-CDC AR bank panel that covers isolates from all presently described geographic clades,16 thus facilitating an exploratory comparative virulence screen. Significant phylogenetic diversity of C. auris isolates from different regions has been reported.1,5,12 Each of the at least four geographically distinct clades was separated by tens of thousands of SNPs, whereas low genetic diversity was found among isolates within each clade.5 Although different mutations were associated with azole resistance in each geographic clade,5 it remains unclear whether these clades exhibit distinct virulence patterns. Consistent throughout three independent runs, the two isolates from the South American clade appeared to exhibit greater virulence capacity in our fly model, with a more pronounced early drop in survival rates. Largely comparable in vitro growth rates of isolates from the South Asian, East Asian and African clade were accompanied by similar survival curves. Given the small amount of strains tested and the under-representation of East Asian isolates in our panel, these exploratory results will require confirmation in a broader range of strains. Studies directly comparing the clinical outcomes of the different clades are scarce. Reviewing 54 C. auris cases from three different continents, Lockhart et al.5 found no increased in-hospital mortality in South American (Venezuelan) patients. A recent study comparing the gene content of C. auris strains from all four clades revealed largely identical gene numbers for key pathogenesis factors such as cell wall adhesins or secreted lipases and proteases.17

Interestingly, we observed no significant difference in growth and virulence of C. auris depending on its aggregative capacity. Two earlier studies performed in Galleria mellonella revealed that non-aggregating C. auris isolates elicit mortality comparable to10 or greater than11C. albicans, whereas aggregate-forming C. auris was less virulent. In contrast, distinct yeast cell aggregates were detected in the kidneys of mice with lethal C. auris infection, suggesting that aggregate formation may serve as an immune evasion mechanism,12,18 e.g. by conferring protection against phagocytic attack.10 As WT Drosophila flies exhibit limited susceptibility to yeast infection,14Tl-deficient flies with impaired antimicrobial peptide release and phagocytic response were utilized,19 possibly contributing to the observation of aggregation-independent survival rates in the Drosophila model. As our findings further affirm the heterogeneity of C. auris virulence capacity in different hosts, exploring virulence differences between different pathosystems could uncover key determinants of C. auris pathogenesis.

There are limitations of our study. Temperature-dependent growth and virulence features such as proteinase secretion20 need to be considered and constitute an important limitation as fly infection studies are performed at 29°C, compared with the higher body temperature (37°C) in mice and humans. Furthermore, we did not evaluate differences in the pathogenicity of each C. auris isolate in the context of its ability to form biofilm, a factor implicated in C. auris virulence.11 Although previous work employing dyed fly food and a bioassay suggests the uptake of bioactive drug concentrations in triazole-exposed flies,21 these methods are cumbersome and provide rather imprecise estimates of drug exposures.15,22 Therefore, pharmacokinetic studies in the Drosophila model are not easily feasible, and drug efficacy data obtained in flies require subsequent validation in mammalian hosts.22

Despite these limitations, this study provides a pilot evaluation of Tl-deficient fruit flies as a model to study C. auris candidiasis, suggesting a potential impact of geographical clades on virulence and documenting high reproducibility of survival rates and fungal burden in a proof-of-concept experiment for azole treatment of flies infected with C. auris isolates displaying different in vitro susceptibility to azoles. As molecular tools to produce loss-of-function mutants in C. auris are being developed23 and investigational drugs are being tested,24 flies could provide an inexpensive and reliable primary screening system to study pathogenesis and drug activity in C. auris candidiasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Lockhart and T. Chiller from CDC for providing the C. auris AR bank strains. Parts of this study were presented at ID Week 2018, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018 (poster presentation; abstract 73236, poster number 380).

Funding

This study was supported by the Texas 4000 Distinguished Professorship for Cancer Research (to D. P. K.) and the NIH National Cancer Institute Cancer Center CORE Support (grant number 16672).

Transparency declarations

D. P. K. reports receiving research support from Astellas Pharma and honoraria for lectures from Merck & Co., Gilead and United Medical. He has served as a consultant for Astellas Pharma, Cidara, Amplyx, Astellas and Mayne, and on the advisory board of Merck & Co. N. D. B. has received research support from and is on the advisory board for Astellas Pharma. I. I. R. is an inventor of nitroglycerin-based and minocycline-based catheter lock solution technologies with activity against Candida in biofilm, licensed by Novel Anti-Infective Technologies, LLC, and Citius Pharmaceuticals in which he is a shareholder. He is also a consultant with Pfizer. All other authors: none to declare.

References

- 1. Osei Sekyere J. Candida auris: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current updates on an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen. Microbiologyopen 2018; 7: e00578.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jeffery-Smith A, Taori SK, Schelenz S et al. Candida auris: a review of the literature. Clin Microbiol Rev 2017; 31: e00029-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deorukhkar SC, Saini S, Mathew S. Non-albicans Candida infection: an emerging threat. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2014; 2014: 615958.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lamoth F, Kontoyiannis DP. The Candida auris alert: facts and perspectives. J Infect Dis 2018; 217: 516–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lockhart SR, Etienne KA, Vallabhaneni S et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64: 134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rossato L, Colombo AL. Candida auris: what have we learned about its mechanisms of pathogenicity? Front Microbiol 2018; 9: 3081.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pathirana RU, Friedman J, Norris HL et al. Fluconazole-resistant Candida auris is susceptible to salivary histatin 5 killing and to intrinsic host defenses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e01872-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Larkin E, Hager C, Chandra J et al. The emerging pathogen Candida auris: growth phenotype, virulence factors, activity of antifungals, and effect of SCY-078, a novel glucan synthesis inhibitor, on growth morphology and biofilm formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 61: e02396–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Welsh RM, Bentz ML, Shams A et al. Survival, persistence, and isolation of the emerging multidrug-resistant pathogenic yeast Candida auris on a plastic healthcare surface. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55: 2996–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borman AM, Szekely A, Johnson EM. Comparative pathogenicity of United Kingdom isolates of the emerging pathogen Candida auris and other key pathogenic Candida species. mSphere 2016; 1: pii: e00189-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sherry L, Ramage G, Kean R et al. Biofilm-forming capability of highly virulent multidrug-resistant Candida auris. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23: 328–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ben-Ami R, Berman J, Novikov A et al. Multidrug-resistant Candida haemulonii and C. auris, Tel Aviv, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23: 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lepak AJ, Zhao M, Berkow EL et al. Pharmacodynamic optimization for treatment of invasive Candida auris infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00791-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chamilos G, Lionakis MS, Lewis RE et al. Drosophila melanogaster as a facile model for large-scale studies of virulence mechanisms and antifungal drug efficacy in Candida species. J Infect Dis 2006; 193: 1014–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamilos G, Samonis G, Kontoyiannis DP. Recent advances in the use of Drosophila melanogaster as a model to study immunopathogenesis of medically important filamentous fungi. Int J Microbiol 2012; 2012: 583792.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leach L, Zhu Y, Chaturvedi S. Development and validation of a real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of Candida auris from surveillance samples. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56: e01223-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Munoz JF, Gade L, Chow NA et al. Genomic basis of multidrug-resistance, mating, and virulence in Candida auris and related emerging species. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fakhim H, Vaezi A, Dannaoui E et al. Comparative virulence of Candida auris with Candida haemulonii, Candida glabrata and Candida albicans in a murine model. Mycoses 2018; 61: 377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lionakis MS, Kontoyiannis DP. The growing promise of Toll-deficient Drosophila melanogaster as a model for studying Aspergillus pathogenesis and treatment. Virulence 2010; 1: 488–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang X, Bing J, Zheng Q et al. The first isolate of Candida auris in China: clinical and biological aspects. Emerg Microbes Infect 2018; 7: 93.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, May GS et al. Toll-deficient Drosophila flies as a fast, high-throughput model for the study of antifungal drug efficacy against invasive aspergillosis and Aspergillus virulence. J Infect Dis 2005; 191: 1188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clemons KV, Stevens DA. The contribution of animal models of aspergillosis to understanding pathogenesis, therapy and virulence. Med Mycol 2005; 43 Suppl 1: S101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Enkler L, Richer D, Marchand AL et al. Genome engineering in the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 35766.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCarthy MW, Kontoyiannis DP, Cornely OA et al. Novel agents and drug targets to meet the challenges of resistant fungi. J Infect Dis 2017; 216: S474–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.