To the Editor:

The oral Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib is a highly effective and usually tolerable therapy for progressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL).1 Therapy is usually continued until treatment failure or intolerance and most patients remain on ibrutinib for an extended period. CLL patients are generally older and can have multiple co-morbidities. Recently published data suggest that at diagnosis of CLL approximately 40% of patients have dyslipidemia or hypertension, 10% have diabetes, and 15% have respiratory disease, and the number of co-morbidities at diagnosis is associated with poorer overall survival.2 The prevalence of these and other co-morbidities would be expected to be even higher by the time treatment is indicated and up to 25% of CLL patients will die from co-morbid health conditions not directly related to CLL.2 Weight control could be important in the management of CLL patients on long term therapy with ibrutinib and especially in those with diabetes and cardiovascular disease.3

Progressive CLL requiring treatment can be associated with decreased appetite and metabolic changes resulting in weight loss. We hypothesize that ibrutinib induced remission reverses these disease-induced effects resulting in significant weight gain. We tested this hypothesis in an observational study.

Clinical data were extracted from medical records for 118 CLL patients treated with ibrutinib for at least 6 months between November 1st, 2011 to June 1st, 2018 at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) James P. Wilmot Cancer Institute. This study was approved by the URMC Internal Review Board. Data on height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were collected 1-year before ibrutinib initiation, at ibrutinib initiation, and after starting ibrutinib therapy at 1,2,3, and 6 months and then at 1-year (n=98), 2 years (n=52), 3 years (n=32), and 4 years (n=14) when available. Patients contributed data for the time points in which they maintained a complete (CR) or partial response (PR) as defined by standard criteria.1

The primary outcome was weight change at 1-year after initiation of ibrutinib therapy. Weight change relative to ibrutinib initiation was also examined at 1,2,3, and 6 months as well as up to 4 years where data were available. Linear mixed models accounted for data coming from the same subject with a subject-specific random intercept term. Time was treated as a categorical fixed effect, as were a priori defined effect modifiers gender and BMI category. To determine the role of CLL-related weight loss during disease progression, sensitivity analyses included weight one year before ibrutinib initiation in patients who did not receive any other treatment in the year before initiation. All models were adjusted for gender, height, and age at ibrutinib initiation. SAS 9.4 was used for all analyses.

The patient population was 61% male with a median age of 67 years at ibrutinib initiation (range 47-88); 44 patients were treatment naïve. Six months after ibrutinib initiation, all patients had responded to treatment. At the time of study completion (median follow up 22.6 months, range 6-77), 77 (65.3%) patients remained on ibrutinib. Forty-one (34.7%) patients stopped therapy with a median duration of therapy of 15.2 months (range 6-46) and were censored at disease progression (n=6) or ibrutinib discontinuation for other reasons. The median weight at ibrutinib initiation was 81kg (range 44 to 125kg), the median BMI was 27 (range 17 to 42) with 2 (1.7%) underweight, 32 (27.1%) normal weight, 57 (48.3%) overweight, and 27 (22.9%) obese.

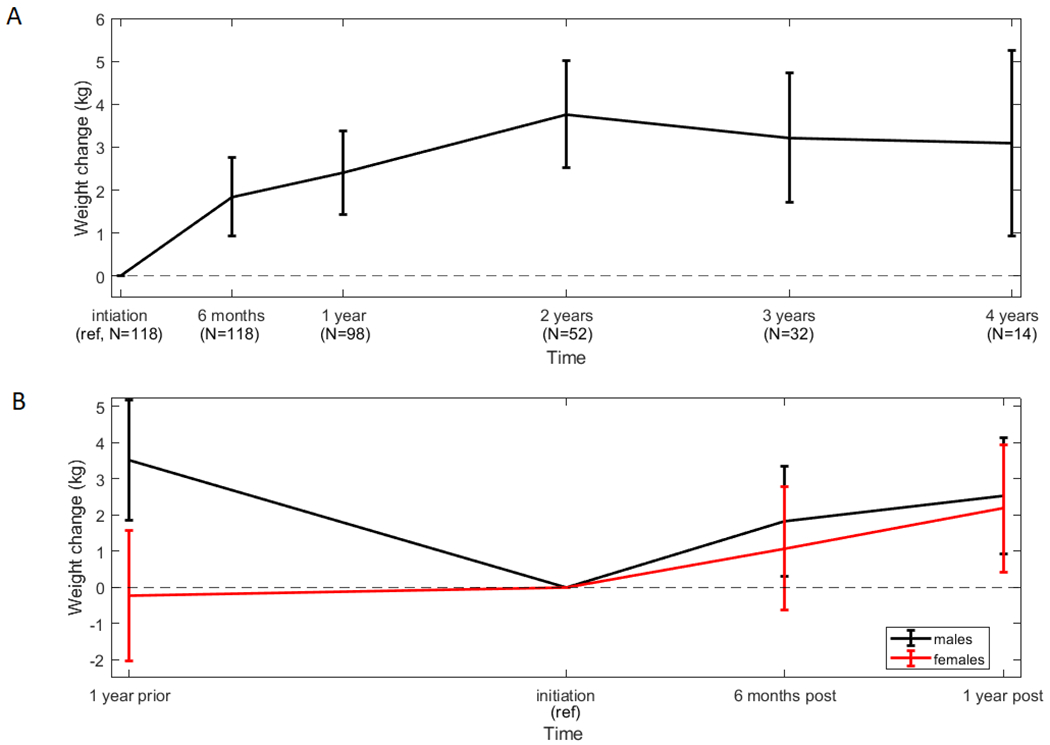

Average patient weight increased after initiation of ibrutinib therapy and was significantly higher at both 6 months and 1-year (Figure 1A). Average weight increase was 1.8 kg at 6 months (β=1.84, 95%CI 1.23-2.45, p<0.001) with 11 patients (9.3%) moving from normal to overweight or obese BMI categories and 11 patients (9.3%) moved from overweight to obese. Average patient weight gain at 1-year was 2.4 kg (β=2.39, 95%CI 1.74-3.04, p<0.001) with 10 (12.5%) patients moving from normal to overweight or obese BMI categories and 9 (11.5%) moving from overweight to obese.

Figure 1. Effect of gender and duration of therapy on weight changes.

Patient weight (mean and 95% confidence interval) increased significantly in the entire patient cohort and was sustained (A). Patient weight changes prior to initiation of ibrutinib therapy were significantly different in men and women (B).

Sensitivity analyses were done to examine how quickly participants gained weight after initiation of ibrutinib therapy. Average patient weight was not statistically different from initiation until 3 months. Subsequently, average weight at one year was significantly higher than at time of initiation of therapy and 1 month, 2 months, and 3 months after initiation (p<0.05). We were interested to see if patient weight gain was sustained beyond 1-year (Figure 1A). At two years after initiation of ibrutinib the average weight of 52 patients who remained on ibrutinib was 3.8 kg higher than at initiation of therapy (β=3.77, 95%CI 2.52-5.01, p<0.001) and had increased significantly in the previous year (p=0.04). In the limited number of patients followed past 2 years, average weight gain appeared to plateau suggesting that weight gain is sustained.

There was evidence of significant differences in weight trajectories by initial BMI category (p=0.02). Underweight and normal-weight patients had the largest weight gain (6 months β=2.96, 95%CI 1.84-4.08; 1-year β=4.34, 95%CI 3.16-5.51), however, patients who were already obese and overweight at initiation of ibrutinib therapy also experienced significant weight gain at 6 months and 1-year compared to treatment initiation (overweight 6 months β=1.13, 95%CI 0.27-1.99 and 1-year β=1.56, 95%CI 0.64-2.48; obese 6 months β=1.93, 95%CI 0.67-3.18 and 1-year β=1.63, 95%CI 0.29-2.97).

To ensure that measured weight gain was not caused by fluid overload we repeated our analysis excluding all 9 time points when patients had clinically apparent edema and results did not change. To determine the effect of CLL related weight loss in the year before initiation of therapy, sensitivity analyses included weight one year prior to ibrutinib initiation in patients who did not receive treatment in the year before initiation (n=70). These patients had a significant increase in weight at 6 months and 1-year compared to treatment initiation (β=1.50, 95%CI 0.32-2.66 and β =2.40, 95%CI 1.18-3.61, respectively). Interestingly, the trajectory of weight loss in the year before initiation varied significantly according to gender (p=0.015, Figure 1B). Women did not lose weight in the year prior to initiation and gained, on average, 2.2 kgs at 1-year post-initiation (β=2.18, 95%CI 0.43-3.93), weighing significantly more than they did one-year before ibrutinib initiation (p=0.01). Men experienced a significant weight loss in the year before ibrutinib initiation, losing on average 3.5 kgs (β=−3.52, 95%CI −1.85 - −5.19). At one-year post-initiation men weighed 2.5 kg more than at initiation (β 2.53, 95%CI 0.93-4.13), however, this was not significantly more than 1-year prior to treatment (p=0.27). Importantly, despite pre-treatment weight loss, 85% of these men were overweight or obese at ibrutinib initiation, indicating that any amount of weight gain may be detrimental.

We report data supportive of the hypothesis that CLL patients responding to ibrutinib therapy have significant and sustained weight gain. These findings are clinically important because two-thirds of our patients were overweight or obese prior to initiation of ibrutinib therapy. The average 2.4 kg weight gain at 1-year after initiation of ibrutinib is higher than the average weight gain over four years in the US population and higher than the 2.25 kg weight gain reported to be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in the Framingham study. 3,4 Given that weight control is a key component of cardiovascular and endocrine comorbidity and up to 27% of CLL patients will die from co-morbid conditions, our study suggests that obesity and weight gain is an important problem in patients responding to ibrutinib therapy2.

Our data on significant weight gain while on treatment for ibrutinib are similar to those reported for other BTK inhibitors including acalabrutinib.5 This suggests that weight gain could be a class effect of BTK inhibition. An alternative and non-exclusive explanation could be that achievement of remission with targeted therapies that are non-cytotoxic and tolerable results in reversal of CLL induced cachexia and weight gain. This hypothesis is additionally supported by a study of weight gain after chemoimmunotherapy treatment in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients that reports significant weight gain up to 18 months post diagnosis6. Determining the cause of weight gain in CLL patients could be important for management.

Our preliminary data suggest that weight gain should be an anticipated side effect of ibrutinib therapy. Patients initiating ibrutinib should be counseled about healthy lifestyle goals, including weight management and even weight loss. Active monitoring of their weight should be incorporated into their care and appropriate referrals should be made once patients appear to be gaining any weight. Weight management aimed at preventing excessive weight gain could be an important component of effective CLL treatment with ibrutinib.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number F99CA222742 to A.M.W.) and the Cadregari Endowment Fund (to C.S.Z.).

References

- 1.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018;131(25):2745–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strati P, Parikh SA, Chaffee KG, et al. Relationship between co-morbidities at diagnosis, survival and ultimate cause of death in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL): a prospective cohort study. British journal of haematology. 2017;178(3):394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Archives of internal medicine. 2002;162(16):1867–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(25):2392–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd JC, Harrington B, O’Brien S, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196) in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374(4):323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynce F, Pehlivanova M, Catlett J, Malkovska V. Obesity in adult lymphoma survivors. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2012;53(4):569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]