Abstract

Objective

To examine whether girls with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) demonstrate positive illusory self-perceptions during adolescence and young adulthood.

Methods

We tested, across a 5-year longitudinal span, whether self-perceptions versus external-source ratings were more strongly predictive of young adulthood impairment and depressive symptoms. Participants included an ethnically diverse sample of 140 girls with ADHD and 88 comparison girls, aged 11–18 years (M = 14.2) at adolescent and 19–24 years (M = 19.6) at young adult assessment.

Results

Although girls with ADHD rated themselves more positively than indicated by external ratings, their self-reports still did not differ significantly from external ratings in both scholastic competence and social adjustment domains. Comparison girls, on the other hand, rated themselves significantly less positively than indicated by external ratings in social adjustment. Positive discrepancy scores in adolescence did not significantly predict depressive symptoms in young adulthood and vice versa. Crucially, measures of actual competence in adolescence were more strongly associated with young adulthood impairments than were inaccurate self-perceptions for girls with ADHD.

Conclusions

Our findings continue to challenge the existence of a positive illusory bias among girls with ADHD, including any association of such bias with key indicators of impairment.

Keywords: ADHD, adolescence, girls, positive illusory bias, young adulthood

Introduction

Individuals with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) typically exhibit significant challenges in academic performance and social functioning (Ek, Westerlund, Holmberg, & Fernell, 2011; Greene et al., 2001; Hinshaw, Owens, Sami, & Fargeon, 2006), with challenges often persisting beyond childhood into adolescence and adulthood (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2006; Hinshaw et al., 2006, 2012; Klein et al., 2012; Mick et al., 2011). Research regarding how individuals with ADHD perceive their own challenges has also been developing, but the literature is mixed. Although some studies have found that self-esteem tends to be lower for youth with ADHD compared with youth without ADHD (Slomkowski, Klein, & Mannuzza, 1995; Treuting & Hinshaw, 2001), some instead find that children (particularly boys, in most studies) with ADHD tend to overestimate their competency, a phenomenon known as the positive illusory bias (PIB; Hoza, Pelham, Milich, Pillow, & McBride, 1993; Hoza et al., 2010; Ohan & Johnston, 2011; Owens, Goldfine, Evangelista, Hoza, & Kaiser, 2007). Positive illusory bias has also been observed among adolescents/young adults with ADHD (Prevatt, Proctor, & Best, 2011). Still, little is known about PIB among females with ADHD during adolescence and young adulthood. Therefore, our primary objective is to examine the presence of PIB in females during adolescence and young adulthood, along with any predictive power of this construct with respect to impairment.

Positive illusory bias can be defined as the disparity or discrepancy between the self-report of competence and “actual” competence, with the former being higher than the latter (Hoza, Pelham, Dobbs, Owens, & Pillow, 2002). Positive illusory bias is an example of what many clinicians have observed as a “lack of insight” on the part of these individuals in evaluating their impairments (Loeber, Green, & Lahey, 1990). This lack of insight might interfere with the pursuit of, adherence to, and effectiveness of behavioral treatments, because such individuals may not believe their symptoms and impairments to be as serious as others perceive them to be (Mikami, Calhoun, & Abikoff, 2010). Thus, the task of detecting whether PIB is present among girls during childhood and beyond carries implications for treatment participation.

Unique Considerations for Female Adolescents and Young Adults

Positive illusions and the “better-than-average” effect have been well-documented in the general population (Alicke & Govorun, 2005; Taylor & Brown, 1988). Among chiefly boys with ADHD it appears to be common, persistent, and functionally impairing (Linnea, Hoza, Tomb, & Kaiser, 2012; McQuade et al., 2011; Ohan & Johnston, 2011). Studies that compared boys and girls with ADHD point to the presence of PIB in each gender, for certain domains; yet findings on gender differences for PIB are mixed. For instance, Owens and Hoza (2003) found gender differences in PIB for the scholastic competence domain, demonstrating that girls overestimated their competence specifically in math, but other studies have not found such a difference in this domain (Evangelista, Owens, Golden, & Pelham, 2008; Hoza et al., 2004). Also, Hoza et al. (2004) found gender differences in PIB for the behavioral domain, with boys overestimating their behavioral conduct competence. Yet Evangelista et al. (2008) found no such difference in this domain. Notably, Hoza et al. (2004) also found significant gender differences in PIB for physical appearance, pointing to an underestimation in girls. Even so, in these studies, samples contained many more boys than girls, so that attempting to establish main effects of gender (Evangelista et al., 2008) or its interaction with ADHD (Hoza et al., 2004; Owens & Hoza, 2003) is relatively underpowered. Furthermore, the presence of PIB across development (e.g., in adolescent girls and young adults with ADHD is under-investigated).

Cultural Considerations

Evidence suggests strongly that as girls mature beyond childhood they face numerous societal and cultural expectations that can adversely affect their self-perceptions and mental well-being (Hinshaw, 2009). There are also indications that the presence of self-enhancing positive illusions may be uncommon for young adult women, given salient cultural expectations like weight or appearance (Strahan, Wilson, Cressman, & Buote, 2006). Additionally, Fredrickson et al.’s (1998) landmark study of young adults completing math tasks in swimsuits suggests that self-objectification depletes mental energy, with young women focusing more on their inadequacies than the task at hand. Likewise, Gonida and Leondari (2011) found that boys typically overestimate their competence whereas girls on average underestimate their competence in math, potentially driven by internalized gender stereotypes.

Positive Illusions in General Populations

In parallel, the better-than-average effect has also been observed to differ by gender in adolescence, with secondary-school boys typically rating themselves higher than girls for several broad positive attributes, regardless of actual differences in performances (Kuyper, Dijkstra, Buunk, & van der Werf, 2011). Taken together, although prevalent in the general population, positive illusions and the better-than-average effect may not be particularly salient among female adolescents and young adults, an observation leading us to hypothesize that among adolescent girls and young adult women with ADHD, PIB may be less salient than for males.

Developmental Issues

What might account for the expected lower levels of positive illusions for adolescent girls? First, even though gender differences in self-perceptions of scholastic competence tend to dissipate from childhood to adolescence, girls consistently outperform boys in school, pointing to a possible discounting of academic abilities even when girls excel (Gentile et al., 2009; Pomerantz, Altermatt, & Saxon, 2002). Second, by adolescence, depressive symptoms continue to rise for girls, with evidence of partial mediation from lower self-perceptions in multiple domains (Eberhart, Shih, Hammen, & Brennan, 2006). Third, with the onset of physical maturity in adolescence, girls not only internalize objectifying cultural attitudes toward their gender (Hinshaw, 2009), but also become more susceptible to lower peer acceptance as their sexual partners increase (Kreager & Staff, 2009). Thus, with the combination of discounting personal achievements, rising depressive symptoms, and negative cultural attitudes that lower social acceptance, adolescent girls may be less inclined to evaluate themselves positively compared with both adolescent boys and pre-adolescent girls.

Implications for Girls with ADHD

The implications for adolescent girls with ADHD are twofold. First, if girls with ADHD demonstrate relatively low levels of positive illusions, the efficacy of reducing positive illusions may not be particularly beneficial. Second, if girls with ADHD do demonstrate positive illusions similar to boys with ADHD, pediatric psychologists may have to contend with the ethical dilemma of either allowing the positive illusions to persist (and thus potentially threatening treatment adherence) or fostering greater self-awareness of ways in which patients are not meeting the high expectations typical adolescent girls already face. Therefore, a key primary objective in this report is to explore whether PIB persists in girls with ADHD beyond childhood.

PIB Domains

It is essential to examine domain-specific forms of PIB. Studies on gender differences in PIB for children with ADHD, although limited, illustrate the importance of examining domains of scholastic competence, behavioral conduct, and physical appearance in female samples (Hoza et al., 2004; Owens & Hoza, 2003). For instance, PIB in the social adjustment domain tends to increase from childhood for typically developing adolescents, whereas PIB in the behavioral competence domain tends to decrease across that span (Hoza et al., 2010). Furthermore, as noted above, positive illusions in the scholastic domain tend to be much less frequent among adolescent girls compared with adolescent boys (Gonida & Leondari, 2011). It is therefore likely that the presence of any PIB might be greater for the social adjustment versus scholastic competence domains. Herein, we were able to assess PIB in the social adjustment and scholastic competence domains, but we unfortunately lack data in the behavioral competence and physical appearance domains.

PIB and Later Impairment

In terms of predictive implications of PIB, Prevatt et al. (2011) revealed academic difficulties among college students with ADHD who also demonstrated PIB. Yet evidence is mixed on the relations between PIB and other impairments, as well as responsiveness to treatment. In fact, as shown in Swanson, Owens, and Hinshaw (2012) with respect to girls with ADHD, low ratings of competence by various external raters (i.e., parents, teachers, clinicians, and objective tests) predicted later functioning more strongly than did the discrepancy scores used to operationalize PIB. We utilize the same sample to extend investigation of whether discrepancy scores versus self-report and external-report better predict later functioning.

This objective also reflects a growing concern—namely, that the PIB itself as it is classically defined and operationalized might be “illusory.” In addition to a potential lack of predictive validity, it could be that any discrepancy between self- and external ratings relates to low competence in individuals with ADHD rather than to overly positive self-perceptions per se. Indeed, several recent investigations appear to reveal that PIB, if it exists, is more a function of low competence than ADHD-related ‘bias’ (Bourchtein, Langberg, Owens, Evans, & Perera, 2017; Jiang & Johnston, 2016; Watabe, Owens, Serrano, & Evans, 2017). We therefore address whether PIB is due primarily to low competence versus illusory self-perceptions of competence—and whether such findings differ by ADHD versus comparison status.

A final issue involves the relation between depressive symptoms and PIB among individuals with ADHD, including its role in the stability of PIB. Intriguing research reveals that low self-perceptions and decreasing positive evaluations are associated with depressive symptoms (McQuade et al., 2011; Ohan & Johnston, 2011). Hoza et al. (2010) found that PIB stability from childhood to adolescence emerged in the domain of social competence, also finding that depression predicted decreases in positive self-perceptions over time. Along with the observation that individuals with ADHD are at risk for developing major depression (Biederman et al., 2008) and given that gender differences in rates of depression may peak during young adulthood (Essau, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Sasagawa, 2010), it is possible that PIB observed in adolescent girls with ADHD would decrease by young adulthood. Likewise, reduced PIB may be associated with increased self-awareness, negative self-evaluations and, thus, greater risk for depressive symptoms. In other words, given the unique challenges faced by girls with ADHD, greater PIB may act as a protective factor against depressive symptoms later in development (Owens et al., 2007). Thus, we evaluate the linkages between discrepancy scores and depressive symptoms.

Aims and Hypotheses

In sum, we propose to expand the relevant literature in several ways. First, we investigate the prevalence of PIB among adolescent girls with and without childhood ADHD. Second, we aim to elucidate the nature of illusory self-perceptions by examining whether self-reports are significantly different from external rater reports for girls with and without ADHD. Third, we examine the predictive power of discrepancy scores versus external ratings of competence in terms of young adult measures of functioning. Finally, we examine longitudinal relations between discrepancy scores and depressive symptoms, as potentially moderated by ADHD status. Our specific hypotheses derive in part from those of Swanson et al. (2012) but are unique to the developmental stages of the present investigation.

Discrepancy scores in the social adjustment domain will be more positive for girls with ADHD than for comparison girls, but discrepancy scores in the scholastic competence domain will not differ significantly between girls with ADHD and comparison girls.

External measures will be significantly more negative than self-report for girls with ADHD but significantly more positive than self-report for comparison girls.

External ratings will predict later impairments in functioning better than discrepancy scores per se.

Larger positive discrepancy scores will predict lower depressive symptoms later in development and higher depressive symptoms will predict smaller positive discrepancy scores later in development.

Methods

Participants

The Berkeley Girls with ADHD Longitudinal Study (BGALS) began with 5-week summer day camps at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1997, 1998, and 1999 (Wave 1; W1). Participants included 140 girls aged 6 to 12 with ADHD (97 with combined type and 43 with predominantly inattentive type), as well as 88 age- and ethnicity-matched comparison girls. The average level of maternal education was “some college” and the average family income (which was measured in the mid-90s) was $50,000–$60,000, slightly higher than the median household income in California in the mid-1990s. Fourteen percent of the sample was receiving some form of public assistance. Thus, although on average somewhat affluent, the sample ranged widely in socioeconomic status. Girls with ADHD and comparison girls did not significantly differ with respect to age, family income, maternal education, ethnicity, receipt of public assistance, or single- versus two-parent status (see online Supplementary Table S1). However, significant differences did emerge for IQ, with girls with ADHD demonstrating lower IQ (M = 99.7, SD = 13.6) scores than comparison girls (M = 112.0, SD = 12.7).

Girls with ADHD were recruited via mailings to various medical settings (including health maintenance organizations), mental health centers, pediatric practices, and local school districts; in addition, advertisements were posted in local newspapers. Comparison girls were recruited through similar mailings to school districts and community centers, as well as parallel advertisements in the local newspapers. The recruited sample had a mean age of 9.6 years and was 53% Caucasian, 27% African American, 11% Latina, 9% Asian American. Following recruitment, full informed consent was obtained. For more details see Hinshaw (2002).

Approximately 5 years later (Wave 2 or W2), follow-up assessments were completed on 209 of 228 participants (92% retention), who ranged from 11.3 to 18.2 years (M = 14.2). Specific reasons for nonparticipation included (a) loss of the family to all tracking efforts (n = 4), (b) refusal of the family to participate (n = 5), and (c) difficulty in scheduling assessments although the family had been contacted (n = 10). Comparison of the retained sample with those lost to attrition revealed that, for 29 of 31 demographic, diagnostic, and symptom variables gathered at baseline, differences were not statistically significant, with the nonretained subgroup possessing higher teacher-reported internalizing symptoms and larger proportions from single-parent homes at baseline. For more details see Hinshaw et al. (2006).

Approximately 10 years after the initial assessment (Wave 3 or W3), follow-up assessments were completed on 216 of the 228 original participants (95% retention), who ranged from 17 to 24 years (M = 19.6). Comparison of the retained sample with those lost to attrition revealed that, for 5 of 23 demographic, diagnostic, and symptom variables gathered at baseline, differences were significant, with the nonretained subgroup (n = 12) being more impaired cognitively and behaviorally. For more details see Hinshaw et al. (2012).

In the investigation of Swanson et al. (2012) study, PIB was investigated across W1 and W2. The current report extends findings to the interval between W2 and W3.

Overview of Procedures

At W2, participants were invited to partake in an assessment that involved two half-day, clinic-based sessions. Five years later (W3), participants were invited for two similar, half-day sessions (Hinshaw et al., 2012). For the few cases wherein clinic participation was not possible, telephone interviews or home visits occurred. During these sessions, we obtained multi-method (objective testing, interview, rating scale, and observation), multi-informant (parent, teacher, and self) data across multiple domains capturing symptoms and impairment, which suited our purpose of comparing external rater and self-reported perceptions.

Measures

External Rater Measures

Measures of Scholastic Competence

Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, 1991 ). At W2, scholastic competence was measured using the academic performance scale from the widely used TRF. This teacher-rated scale indexes performance below, at, or above grade level in various academic subjects. Each of up to six items are scored on a 1–5 scale in various academic subjects. These scores are then averaged across the items and converted to T scores. Teachers were selected by asking the parent to indicate which of the child’s academic teachers knows the child best. Test–retest reliability of the TRF Academic Performance scale is 0.93. Among adolescents referred for services, teacher ratings correlated r = .55.

Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WIAT; Wechsler, 1992). At W2 and W3, we created scholastic competence ratings by averaging the Basic Reading and Math Reasoning subtest scores of the WIAT. The WIAT is a psychometrically sound, widely used test of achievement. Test–retest reliabilities for the Reading and Math subtest scores range from 0.85 to 0.92 (Wechsler, 1992).

Measures of Social Adjustment

Dishion Social Preference Scale (Dishion, 1990). This is a three-item, teacher-completed measure of the proportion of peers who accept, reject, and ignore the adolescent in question, with each item rated on a 5-point scale. Dishion has reported moderately strong correlations with peer-derived sociometric indicators. Internal consistency reliability has been demonstrated to be strong (α = .80; Dishion, Kim, Stormshak, & O’Neill, 2014). From the ratings at W2, we derived a widely used and well-validated social preference score (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982; Lahey et al., 2004) by subtracting the reject rating from the accept rating (Hinshaw et al., 2006). We used this social preference score to index social adjustment at W2.

Social Relationships Questionnaire (SRQ). This is a parent-reported measure of an adolescent’s relationships with peers and friends containing 12 items, each of which is scored on a 4-point metric. A principal components analysis of these items yielded two factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, accounting for 44% and 11% of the variance, respectively. An oblique rotation yielded two factors, each comprising six items, which we termed Peer Conflict (α = .83) and Friendship (α = .77). In this study, we utilized the Friendship subscore from W2.

Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2003). The parent-rated ABCL has good-to-excellent reliability and validity (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2003). Each of the four items is rated on a 0–2 metric, and we utilized the “friends” T score from W3 to measure the mother’s perception of participants’ social adjustment.

Self-report Measures of Competence and Depressive Symptoms

Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA; Harter, 1988). On the SPPA, adolescents make self-reports on the extent to which they agree with various statements reflecting perceived competence across several domains. We used the domains of Social Adjustment and Scholastic Competence (each with five items) from both W2 and W3. As reported by Harter (1982), internal consistencies of these scales ranged from 0.75 to 0.84, with test–retest reliabilities ranging from 0.69 to 0.80. Internal consistencies for the present sample were 0.74 and 0.76 for the Social Adjustment and Scholastic Competence domain, respectively.

Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992). The total score from the CDI was used to measure symptoms of depression in youth. The psychometric properties of this measure are favorable, with test–retest reliability scores averaging 0.70 (Kovacs, 1992). Internal consistency for this sample was 0.85. Each of the 27 items is scored on a 0–2 metric.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996). The BDI is a widely used and extensively validated 21-item self-report instrument that measures symptoms of depression in adults, replacing the CDI at W3. Its psychometric properties are excellent. Internal consistency for this sample was 0.93.

Measures of Functional Impairment

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994). The GAF ranges from 1 (worst) to 100 (best) and is intended to capture psychological, social, and occupational functioning. At W3 we averaged two clinician-rated Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; APA, 1994) scores, one generated after a 4-hr parent assessment and the other generated after an 8-hr participant assessment. During these assessments clinicians used semi-structured interviews, rating scales, and objective tests to gather information across multiple domains of symptomatology and impairments (e.g., ADHD symptoms, externalizing and internalizing problems, substance use, eating disorders, academic achievement, well-being, service utilization, self-harm, problematic driving, and global impairment [Hinshaw et al., 2012]). Clinicians also obtained information regarding personality, neuropsychological functioning, family relationships, peer and romantic relationships, coping and social support, and stressful life events before rating participants on the GAF. Ratings from the clinician who interviewed the participant were correlated r = .70 with ratings from the clinician who interviewed the parent.

Data Analytic Plan

Operationalizing PIB typically involves calculating a discrepancy score by subtracting self-report from external rater report, usually that of a teacher, parent, or clinician (Owens et al., 2007). Ideally, discrepancy scores are calculated using parallel forms of the same measure for different informants. In the present study, similar measures were not uniformly utilized for both participants and informants. Therefore, we used a standardized discrepancy score method (De Los Reyes & Kazdin 2004), in which self-report and external rater measures are separately standardized with the total sample before a difference is calculated between the two. In their review, De Los Reyes and Kazdin found that of discrepancy score methods, only the standardized discrepancy method was uniformly correlated with the ratings from which it was calculated.

Specifically, after standardization, the TRF (W2) and WIAT (W2 and W3) scores were subtracted from Harter Scholastic Competence scores; the Dishion Social Preference (W2), Social Relationships Questionnaire (SRQ) Friendship (W2), and ABCL Friends (W3) scores were subtracted from Harter’s Social Acceptance score. Thus, we had three discrepancy scores within the scholastic domain (two at W2 and one at W3) and three within the social adjustment domain (two at W2 and one at W3).

To test Hypothesis 1, we compared these six discrepancy scores across diagnostic groups (ADHD vs. comparison girls) via independent-samples t-tests. Next, we tested Hypothesis 2 by utilizing paired-samples t-tests to assess whether the self-report versus external rater scores within the same domains and diagnostic groups were significantly different from each other.

In addition, and in parallel to Swanson et al. (2012), we addressed Hypothesis 3 by using hierarchical regressions to test the relative ability of discrepancy scores versus external rater scores at W2 to predict W3 functioning (as measured by the GAF). This strategy contrasts with other methodologies that aim to predict later outcomes from discrepancy scores alone. Specifically, we not only used a discrepancy score from each domain to predict later functioning, but we also adjusted for a different external rater score of the same domain that was not a part of the calculated discrepancy, as suggested by Pedhazur and Schmelkin (1991)—hence the need for two external rater measures during W2. In our hierarchical regressions predicting GAF scores, we first covaried ADHD diagnostic status and then for an external rater score that was not used to calculate the discrepancy score.

Finally, to address Hypothesis 4, we used hierarchical regressions to test the relative ability of discrepancy scores versus external rater scores at W2 to predict later depressive symptoms as measured by the BDI, using the same strategies from Hypothesis 3 to address possible collinearity and adjust for ADHD diagnosis. We also used simple regression to test whether depressive symptoms in W2 as measured by the CDI predict later discrepancy scores in W3.

To balance Type I and Type II error, we applied a Benjamini–Hochberg correction (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) to all significant p values within each hypothesis. Only findings that were still significant at 0.05 levels after correction are reported here (but all p values reported are precorrection). All statistical analyses were conducted in R 0.99.473 (R Core Team, 2015).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Rates of missing values ranged from 7% to 33%, averaging 14.8% across the 12 study variables. Variables with the highest rate of missing values (33%) were the TRF and Dishion Social Preference Scale. W1 income, IQ, and internalizing/externalizing symptoms were related to the presence/absence of these missing values, revealing that the data were not missing at random. Consequently, we did not utilize imputation or bootstrapping to replace or simulate the missing values, given that such methods rely on the assumption of data missing at random. Missing values were excluded from individual analyses automatically through R.

In Table I, diagnostic group differences in the scholastic competence domain at W2 and W3 were significant (p = .000) with medium to very large effects (ds = 0.61–1.21). Similarly, the Social Adjustment domain had significant differences with medium to large effects (ds = 0.42–1.10) for all measures except Harter’s Social Acceptance score W3 (p = .028; d = 0.32).

Table I.

Average Perceptions of Scholastic Competence and Social Adjustment for ADHD and Comparison Girls

| Component scorea | ADHD | Comparison | Effect sizeb | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescence | ||||

| Scholastic competence | ||||

| Harter’s | 2.78 (0.60) | 3.22 (0.63) | 0.72 | <.001* |

| WIAT | 96.08 (25.56) | 110.33 (9.92) | 1.21 | <.001* |

| TRF | 43.86 (8.26) | 54.00 (9.46) | 1.16 | <.001* |

| Social adjustment | ||||

| Harter’s | 3.12 (0.65) | 3.36 (0.48) | 0.42 | .002* |

| Dishion | 1.65 (2.38) | 3.11 (1.30) | 0.71 | <.001* |

| SRQ | 0.33 (0.69) | 0.97 (0.38) | 1.10 | <.001* |

| Young adulthood | ||||

| Scholastic competence | ||||

| Harter’s | 2.68 (0.66) | 3.06 (0.60) | 0.61 | <.001* |

| WIAT | 94.23 (13.77) | 107.36 (9.18) | 1.08 | <.001* |

| Social adjustment | ||||

| Harter’s | 3.09 (0.64) | 3.30 (0.66) | 0.32 | .028* |

| ABCL | 46.17 (9.19) | 52.93 (7.13) | 0.80 | <.001* |

Note. WIAT scores reflect an average of the Basic Reading and Math Reasoning subtests. We used the TRF Academic Performance subscale, the SRQ Friendship subscore, and the ABCL “friend” subscore for these analyses. ABCL = Adult Behavior Checklist; ADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Dishion = Dishion Social Preference Scale; Harter’s = Harter’s Self-Perception Profile; SRQ = Social Relationships Questionnaire; TRF = Teacher Report Form; WIAT = Wechsler Individual Achievement Test.

Component scores were first standardized before comparing across groups.

Effect size is Cohen’s d, reflecting contrast of absolute scores for ADHD versus Comparison girls: 0.20 = small, 0.50 = medium, 0.80 = large.

p < .05 after Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

Primary Analyses

Hypothesis 1: Discrepancy scores in the social adjustment domain will be more positive for girls with ADHD than for comparison girls, while discrepancy scores in the scholastic competence domain will not differ between girls with ADHD and comparison girls.

On average, girls with ADHD had positive discrepancy scores, indicating possible presence of PIB, whereas comparison girls had negative discrepancy scores, indicating under-reporting of competence (Table II). In the Scholastic Competence domain, the diagnostic group differences between the discrepancy scores were not significant. In the Social Adjustment domain, the differences between the discrepancy scores were significant for the SRQ Friendship score (d = 0.48, p = .001), but not for the Dishion Social Preference Scale (d = 0.21, p = .170) or the ABCL Friends score (d = 0.30, p = .056). These findings align with our hypothesis.

Table II.

Average Discrepancy Scores of Scholastic Competence and Social Adjustment for ADHD and Comparison Girls

| Discrepancy scorea | ADHD | Comparison | Effect sizeb | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescence | ||||

| Scholastic competence | ||||

| WIAT | 0.11 (1.19) | 0.22 (0.99) | 0.29 | .036 |

| TRF | 0.13 (1.27) | 0.22 (0.89) | 0.32 | .046 |

| Social adjustment | ||||

| Dishion | 0.10 (1.33) | 0.16 (0.95) | 0.21 | .170 |

| SRQ | 0.18 (1.14) | 0.31 (0.81) | 0.48 | .001* |

| Young adulthood | ||||

| Scholastic competence | ||||

| WIAT | 0.09 (1.30) | 0.22 (0.95) | 0.27 | .050 |

| Social adjustment | ||||

| ABCL | 0.12 (1.31) | 0.25 (1.08) | 0.30 | .056 |

Note. WIAT scores reflect an average of the Basic Reading and Math Reasoning subtests. We used the TRF Academic Performance subscale, the SRQ Friendship subscore, and the ABCL “friends” subscore for these analyses. ABCL = Adult Behavior Checklist; ADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Dishion = Dishion Social Preference Scale; SRQ = Social Relationships Questionnaire; TRF = Teacher Report Form; WIAT = Wechsler Individual Achievement Test.

Discrepancy scores were calculated by subtracting given informant measures from the Harter’s self-report measures.

Effect size is Cohen’s d, reflecting contrast of absolute scores for ADHD versus Comparison girls: 0.20 = small, 0.50 = medium, 0.80 = large.

p < .05 after Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

Hypothesis 2: External measures will be significantly more negative than self-report for girls with ADHD and significantly more positive than self-report for comparison girls.

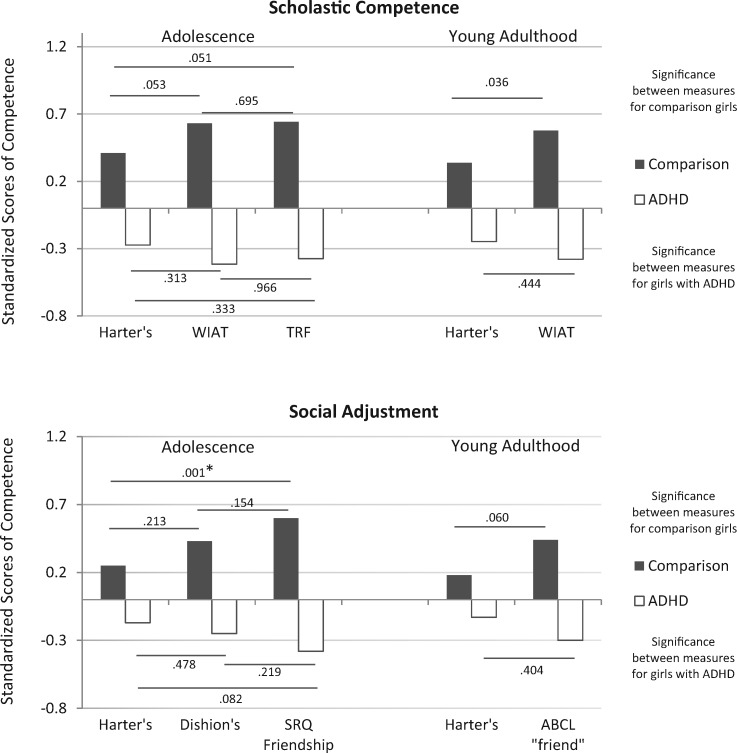

For girls with ADHD, the differences between self- and external ratings of competencies were not significant, as seen in Figure 1 (Harter vs. WIAT W2 d = 0.15, p = .313; Harter vs. TRF d = 0.11, p = .333; Harter vs. WIAT W3 d = 0.13, p = .444; Harter vs. Dishion’s d = 0.08, p = .478; Harter vs. SRQ d = 0.20, p = .082; Harter vs. ABCL d = 0.29, p = .404). Paired t-tests in Figure 1 do reveal a significant difference, though, between the Harter self-report measure and the SRQ at adolescence for comparison girls (p = .001, d = 0.50).

Figure 1.

Average perceptions of competence in the domains of scholastic competence (top chart) and social adjustment (bottom chart). Absolute scores were obtained from four different measures and then standardized for comparison purposes. The “0” value corresponds to the means within each measure regardless of diagnostic status. WIAT scores reflect an average of the Basic Reading and Math Reasoning subtests. We used the TRF Academic Performance subscale, the SRQ Friendship subscore, and the ABCL “friends” subscore for these analyses. The significance values labeling the lines between the bars refer to the differences between measures for a given diagnostic group. *p < .05 after Benjamini–Hochberg correction. ABCL = Adult Behavior Checklist; Dishion = Dishion Social Preference Scale; Harter’s = Harter’s Self-Perception Profile; SRQ = Social Relationships Questionnaire; TRF = Teacher Report Form; WIAT = Wechsler Individual Achievement Test.

Hypothesis 3: External ratings will predict later impairments in functioning better than discrepancy scores.

Table III summarizes our findings for the Scholastic Competence and Social Adjustment domains. Predictors included (1) the TRF versus the WIAT discrepancy, (2) the WIAT versus the TRF discrepancy score, (3) the Dishion Social Preference versus the SRQ discrepancy score, and (4) the SRQ versus the Dishion Social Preference discrepancy score. As expected, the ADHD diagnosis significantly predicted later functioning (ΔR2 = .24, p < .001). Only the TRF and SRQ scores predicted better functioning in young adulthood (TRF ΔR2 = .02, p = .011; SRQ ΔR2 = .04, p = .005), with no other component and no discrepancy scores significantly associated with outcomes.

Table III.

Association of Adolescent Scholastic Competence and Social Adjustment Measures and Discrepancy Scores with Young Adulthood Functioning

| Predictor | ΔR 2 | B | SEB | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: ADHD | .24 | 13.12 | 1.60 | .000* |

| Scholastic competence | ||||

| Set 1: | ||||

| Step 2: TRF | .07 | .28 | .11 | .011* |

| Step 3: DS WIAT | .00 | .38 | .81 | .639 |

| Set 2: | ||||

| Step 2: WIAT | .02 | .07 | .03 | .036 |

| Step 3: DS TRF | .03 | .83 | .84 | .320 |

| Social adjustment | ||||

| Set 1: | ||||

| Step 2: Dishion | .01 | .66 | .49 | .182 |

| Step 3: DS SRQ | .00 | .02 | 1.00 | .988 |

| Set 2: | ||||

| Step 2: SRQ | .04 | 4.05 | 1.41 | .05* |

| Step 3: DS Dishion | .00 | .39 | .82 | .632 |

Note. WIAT scores reflect an average of the Basic Reading and Math Reasoning subtests. We used the TRF Academic Performance subscale and the SRQ Friendship subscore for these analyses. Dependent Variable: GAF. ADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Dishion = Dishion Social Preference Scale; DS = Discrepancy score; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; SRQ = Social Relationships Questionnaire; TRF = Teacher Report Form; WIAT = Wechsler Individual Achievement Test.

p < .05 after Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

Hypothesis 4: Larger positive discrepancy scores will predict lower depressive symptoms later on and higher depressive symptoms will predict smaller positive discrepancy scores later on.

Diagnostic status did not significantly predict depressive symptoms during young adulthood (p = .042). Furthermore, no component or discrepancy scores significantly predicted depressive symptoms during young adulthood (component scores p range = .037–.372; discrepancy scores p range = .233–.964), contrary to our hypotheses. Similarly, depressive symptoms in adolescence did not significantly predict discrepancy scores in young adulthood (WIAT DS: p = .449; ABCL DS: p = .588).

Discussion

In our investigation, we examined whether PIB is present in adolescent and young adult girls with ADHD, as well as whether any apparent PIB was associated with functional outcomes and depressive symptoms. Our findings were as follows: (a) real challenges existed for girls with ADHD in adolescence and young adulthood in both scholastic competence and social adjustment domains, as indicated by both self-report and external rater measures; (b) the difference between self-report and external rater scores was not significant for girls with ADHD, whereas for one social adjustment measure it was significantly different for comparison girls, who tended to under-report adjustment; (c) adolescent competence as reported by external raters predicted young adult functional outcomes whereas discrepancy scores did not significantly account for additional variance in such predictions; and (d) discrepancy scores and depressive symptoms were not significantly associated. In short, we did not find evidence for PIB in this sample. Our key conclusion is that PIB may not be as prevalent or clinically relevant as has been previously assumed, particularly among girls with ADHD.

Only discrepancy scores in the social adjustment domain during adolescence were significantly different for ADHD versus comparison girls, appearing to indicate PIB in self-perceptions of social adjustment for adolescent girls with ADHD. However, self- and external ratings did not differ significantly for girls with ADHD (for parallel findings during childhood in this sample, see Swanson et al., 2012). Furthermore, ratings of girls with ADHD and external raters were both in the negative direction, on average, indicating greater self-awareness of impairments than the PIB literature might predict. To call such a discrepancy a “positive” illusory bias could be misleading, because these girls were not actually rating themselves positively, as highlighted by Swanson et al. (2012).

What, then, might account for the significant difference in discrepancy scores between girls with ADHD and comparison girls? As seen in Figure 1, the only significant difference between measures arose from comparison girls, indicating a significant under-evaluation of competence. Indeed, differences for a given discrepancy score are naturally linked to differences between component scores that make up such a discrepancy (see also Swanson et al., 2012, for parallel findings during childhood). Therefore, what might be interpreted as PIB in girls with ADHD could instead be the presence of under-reporting of self-competence by comparison girls versus girls with ADHD (for additional evidence of underestimation of competence in female samples, see Gonida & Leondari, 2011; Kuyper et al., 2011).

Notably, other recent investigations have addressed the adequacy of discrepancy scores as an operationalization for PIB. Specifically, latent profile analysis (Bourchtein et al., 2017) and experimental control of competence (Jiang & Johnston, 2016; Watabe et al., 2017) have been explored as alternatives to discrepancy scores in detecting PIB. Importantly, PIB as operationalized by these approaches was neither ubiquitous in these samples of individuals with ADHD (Bourchtein et al., 2017; Jiang & Johnston, 2016) nor related to ADHD status (Watabe et al., 2017). Additionally, we highlight that although self- and external ratings did not differ significantly for girls with ADHD, the effect sizes across raters still ranged from .08 to .29, small but perhaps meaningful. Thus, it may still be important to utilize multi-informant ratings in assessing competence.

In addition, discrepancy scores did not predict later functioning better than component scores, in line with our hypotheses. In fact, as found by Swanson et al. (2012) for the present sample during childhood, component scores accounted for more variance than did discrepancy scores, adjusting for ADHD diagnosis. Likewise, studies adjusting for competence have shown that PIB is a function of greater impairment (Jiang & Johnston, 2016) and low competence (Watabe et al., 2017) rather than of overinflated self-reports in individuals with ADHD (see also Linnea et al., 2012; McQuade et al., 2011; Ohan & Johnston, 2011). Indeed, when we examined our sample in childhood (Wave 1) girls with ADHD did possess significantly lower IQ than their comparison counterparts (Hinshaw, 2002), further supporting the possibility that, counter to the findings of Hoza et al. (2010), lower competence co-occurs with self-awareness of deficits in individuals with ADHD (Bourchtein et al., 2017).

Surprisingly, neither component scores nor discrepancy scores significantly predicted depressive symptoms in young adulthood. As well, depressive symptoms also did not predict discrepancy scores in young adulthood, indicating that a longitudinal relation between discrepancy score and depressive symptoms cannot be confidently established in either temporal direction. Taken together, these findings both affirm and challenge those of Hoza et al. (2010), who found that positive biases did not significantly predict depressive symptoms over time (in line with our findings) but also that depression predicted decreases in positive self-perceptions (contrary to our findings).

We can think of three possible explanations for these results. First, most studies examining depressive symptoms and discrepancy scores did so by adhering to a cutoff of symptoms and comparing discrepancy scores between those above or below that cutoff (Hoza et al., 2002, 2004; Ohan & Johnston, 2011). As our study examined depressive symptoms as a continuous variable, we addressed a different research question than that posed by the dichotomization of the depressive symptom variable. Second, although Hoza et al. (2010) did observe a significant linear relation between depressive symptoms and discrepancy scores, they noted that the effect size was small, pointing to the possibility that our current analyses are possibly underpowered to detect such an effect. However, as the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence, it is still possible that such a relation could exist. Third, all these studies primarily predicted outcomes from childhood to adolescence, whereas ours examined outcomes at young adulthood. It may be the case that any effect of adolescent self-perceptions or objective competence on depressive symptoms may be lessened by young adulthood, related to higher depressive symptoms being more common for young adult women.

Limitations and Conclusions

Our all-female sample allowed examination of possible illusory biases among females with ADHD, but our findings are limited in that we cannot directly compare results for girls and boys. Given the still-sparse literature on females with ADHD, we believe that the findings carry clinical importance. Second, our sample also possessed a slightly higher socioeconomic status (SES) on average than comparable populations of that region and year, so generalizability may be limited. Third, regarding measurement, we were unable to use the parallel Harter adult-informant report form as the external rater report, which limits our ability to make direct comparisons between the discrepancy scores of this study and those of other investigations featuring the Harter scale. Also, because approximately one-fifth of our participants did not live at home during young adulthood, the parent-report measures (i.e., the ABCL and the GAF utilizing clinicians who interviewed the parent) may not have been fully accurate. Finally, missing data from teachers and the possible inflation of effect sizes due to use of standardized scores are additional limitations. We advise that these results be interpreted carefully.

These findings point to several clinical implications that may be of interest to pediatric clinicians. First, it seems that adolescent girls in general may have overly negative opinions of their competencies, viewing their performance in academic and social domains more poorly than perhaps they should. In Gentile et al. (2009), academic and social domains of self-esteem in girls were demonstrated to align with the “reflected appraisals” model of self-esteem, which posits that self-esteem is primarily rooted in others’ perceptions of the self (Leary, Haupt, Strausser, & Chokel, 1998), as opposed to actual competence. Thus, it may be helpful for pediatric psychologists who treat adolescent girls to address the specific sociocultural influences on their patients’ academic and social self-perceptions (e.g., cultural perceptions of academic competence, the impacts of relational aggression, and the like). Second, even in the presence of significantly lower IQ than comparison girls, girls with ADHD may view themselves relatively accurately, an idea that is diametrically opposed to the persistent idea that adolescents with ADHD view themselves more positively than they should. This finding affirms the possibility that adolescents with ADHD can be valid informants of their competence in academic and social domains (Chan & Martinussen, 2016). Third, our findings indicate that higher discrepancy scores did not predict global functioning in young adulthood. Thus, when pediatric psychologists do encounter adolescents with a seemingly inflated sense of self-competence, it may not be necessary to intervene by helping adolescents match perceptions to performance (Watabe et al., 2017). Historically, it was thought that full self-awareness of children’s challenges was necessary for them to be willing to address them (Gresham et al., 1998). With such individuals, focusing on increasing competences in domains of deficiency may be a more direct avenue of intervention.

To determine whether our findings are unique to female adolescents with ADHD or if they generalize to all individuals with ADHD, future research that includes both male and female samples is necessary. Additionally, as our findings only speak to competencies in social and scholastic domains, further research in other domains of competence (i.e., behavioral) would be important for applying our clinical recommendations broadly.

Overall, a close examination of the component scores underlying supposed PIB, and the lack of predictive validity of discrepancy scores, suggest that PIB in adolescent girls and young adults with ADHD could be a misnomer. Our findings challenge prevailing theories about the nature of PIB in females with ADHD and imply that a full understanding of both self-perceptions and external indicators of competence is necessary. In the meantime, we recommend that the term “positive illusory bias” be utilized with caution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the work of Christine A. Zalecki, Peter Gillette, and all the researchers of the Hinshaw Lab. We also wish to deeply thank the young women and their parents who participated in our project.

Funding

This research was supported by the NIMH (R01 45064).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Achenbach T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. M., Rescorla L. A. (2003). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Alicke M. D., Govorun O. (2005). The better-than-average effect. In Alicke M. D., Dunning D. A., Krueger J. I. (Eds.), The self in social judgment (pp. 85–106). New York, NY: Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R. A., Fischer M., Smallish L., Fletcher K. (2006). Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., Ball R., Ranieri W. F. (1996). Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories–IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67, 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J., Ball S. W., Monuteaux M. C., Mick E., Spencer T. J., McCreary M., Faraone S. V. (2008). New insights into the comorbidity between ADHD and major depression in adolescent and young adult females. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourchtein E., Langberg J. M., Owens J. S., Evans S. W., Perera R. A. (2017). Is the positive illusory bias common in young adolescents with ADHD? A fresh look at prevalence and stability using latent profile and transition analyses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1063–1075. doi:10.1007/s10802-016-0248-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan T., Martinussen R. (2016). Positive illusions? The accuracy of academic self-appraisals in adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41, 799–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie J. D., Dodge K. A., Coppotelli H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A., Kazdin A. E. (2004). Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychological Assessment, 16, 330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T. (1990). The peer context of troublesome child and adolescent behavior. In Leone P. E. (Ed.), Understanding troubled and troubling youth (pp. 128–153). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T., Kim H., Stormshak E. A., O’Neill M. (2014). A brief measure of peer affiliation and social acceptance (PASA): Validity in an ethnically diverse sample of early adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart N. K., Shih J. H., Hammen C. L., Brennan P. A. (2006). Understanding the sex difference in vulnerability to adolescent depression: An examination of child and parent characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek U., Westerlund J., Holmberg K., Fernell E. (2011). Academic performance of adolescents with ADHD and other behavioural and learning problems—A population-based longitudinal study. Acta Pædiatrica, 100, 402–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau C. A., Lewinsohn P. M., Seeley J. R., Sasagawa S. (2010). Gender differences in the developmental course of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 127, 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista N. M., Owens J. S., Golden C. M., Pelham W. E. (2008). The positive illusory bias: Do inflated self-perceptions in children with ADHD generalize to perceptions of others? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 779–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. L., Roberts T.-A., Noll S. M., Quinn D. M., Twenge J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile B., Grabe S., Dolan-Pascoe B., Twenge J. M., Wells B. E., Maitino A. (2009). Gender differences in domain-specific self-esteem: a meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 13, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gonida E. N., Leondari A. (2011). Patterns of motivation among adolescents with biased and accurate self-efficacy beliefs. International Journal of Educational Research, 50, 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Greene R., Biederman J., Faraone S., Monuteaux M., Mick E., DuPRE E., Goring J. (2001). Social impairment in girls with ADHD: patterns, gender comparisons, and correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham F. M., MacMillan D. L., Bocian K. M., Ward S. L., Forness S. R. (1998). Comorbidity of hyperactivity-impulsivity-inattention and conduct problems: Risk factors in social, affective and academic domains. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. (1988). Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. Unpublished manuscript, University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw S. P. (2002). Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyper-activity disorder: I. Background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive and social functioning, and parenting practices. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1086–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw S. P., Owens E. B., Sami N., Fargeon S. (2006). Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adolescence: Evidence for continuing cross-domain impairment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw S., Kranz R. (2009). The triple bind: Saving our teenage girls from today's pressures. Ballantine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw S. P., Owens E. B., Zalecki C., Huggins S. P., Montenegro-Nevado A. J., Schrodek E., Swanson E. N. (2012). Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: Continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 1041–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B., Gerdes A. C., Hinshaw S. P., Arnold L. E., Pelham W. E., Molina B. S. G., Wigal T. (2004). Self-perceptions of competence in children with ADHD and comparison children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B., Murray-Close D., Arnold L. E., Hinshaw S. P., Hechtman L.; The MTA Cooperative Group. (2010). Time-dependent changes in positively biased self-perceptions of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 375–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B., Pelham W. E. Jr., Dobbs J., Owens J. S., Pillow D. R. (2002). Do boys with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder have positive illusory self-concepts? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B., Pelham W. E., Milich R., Pillow D., McBride K. (1993). The self-perceptions and attributions of attention deficit hyperactivity disordered and nonreferred boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21, 271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Johnston C. (2017). Controlled social interaction tasks to measure self-perceptions: No evidence of positive illusions in boys with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1051–1062. doi:10.1007/s10802-016-0232-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. G., Mannuzza S., Olazagasti M. A. R., Roizen E., Hutchison J. A., Lashua E. C., Castellanos F. X. (2012). Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 1295–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. (1992). Manual: Children’s depression inventory. Toronto, Canada: Multihealth Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Kreager D. A., Staff J. (2009). The sexual double standard and adolescent peer acceptance. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72, 143–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper H., Dijkstra P., Buunk A. P., van der Werf M. P. (2011). Social comparisons in the classroom: An investigation of the better than average effect among secondary school children. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 25–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary M. R., Haupt A. L., Strausser K. S., Chokel J. T. (1998). Calibrating the sociometer: the relationship between interpersonal appraisals and the state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1290–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey B. B., Pelham W. E., Loney J., Kipp H., Ehrhardt A., Lee S. S., et al. (2004). Three-year predictive validity of DSM IV attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4 6 years of age. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 2014–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnea K., Hoza B., Tomb M., Kaiser N. (2012). Does a positive bias relate to social behavior in children with ADHD? Behavior Therapy, 43, 862–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R., Green S. M., Lahey B. B. (1990). Mental health professionals’ perception of the utility of children, mothers, and teachers as informants on childhood psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- McQuade J., Tomb M., Hoza B., Waschbusch D. A., Hurt E. A., Vaughn A. J. (2011). Cognitive deficits and positively biased self-perceptions in children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 307–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick E., Byrne D., Fried R., Monuteaux M., Faraone S. V., Biederman J. (2011). Predictors of ADHD persistence in girls at 5-year follow-up. Journal of Attention Disorders, 15, 183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami A., Calhoun C., Abikoff H. (2010). Positive illusory bias and response to behavioral treatment among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39, 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur E. J., Schmelkin L. P. (1991). Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz E. M., Altermatt E. R., Saxon J. L. (2002). Making the grade but feeling distressed: Gender differences in academic performance and internal distress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Prevatt F., Proctor B., Best L. (2011). The positive illusory bias: Does it explain self-evaluations in college students with ADHD? Journal of Attention Disorders, 15, 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohan J., Johnston C. (2011). Positive illusions of social competence in girls with and without ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 527–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J. S., Goldfine M. E., Evangelista N. M., Hoza B., Kaiser N. M. (2007). A critical review of self-perceptions and the positive illusory bias in children with ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10, 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J. S., Hoza B. (2003). The role of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in the positive illusory bias. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 680–691. doi:10.1037/0022- 006X.71.4.680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Computer software]. Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Slomkowski C., Klein R. G., Mannuzza S. (1995). Is self-esteem an important outcome in hyperactive children? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahan E. J., Wilson A. E., Cressman K. E., Buote V. M. (2006). Comparing to perfection: How cultural norms for appearance affect social comparisons and self-image. Body Image, 3, 211–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson E. N., Owens E. B., Hinshaw S. P. (2012). Is the positive illusory bias illusory? Examining discrepant self-perceptions of competence in girls with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 987–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. E., Brown J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treuting J. J., Hinshaw S. P. (2001). Depression and self-esteem in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Associations with comorbid aggression and explanatory attributional mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe Y., Owens J. S., Serrano V., Evans S. W. (2017). Is positive bias in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder a function of low competence or disorder status? Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 26, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1992). Wechsler individual achievement test. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.