Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most common and aggressive brain tumor in adults. Most patients die within a year and long-term survival remains rare, owing to a combination of rapid progression/degeneration, lack of successful treatments, and high recurrence rates. Extracellular vesicles are cell-derived membranous structures involved in numerous physiological and pathological processes. In the context of cancer, these biological nanoparticles play an important role in intercellular communication, allowing cancer cells to exchange information with each other, the tumor microenvironment as well as distant cells. Here, light is shed on the role of extracellular vesicles in glioblastoma heterogeneity, tumor microenvironment interactions, and therapeutic resistance, and an overview on means to track their release, uptake, and cargo delivery is provided.

Keywords: EV tracking, extracellular vesicles, treatment resistance, tumor microenvironment

1. Background

1.1. Glioblastoma

Gliomas account for around 27% of primary and 80% of all malignant central nervous system tumors.[1] Glioblastoma (GBM), which encompasses 54% of all gliomas, is the most malignant form in adults with a five-year survival rate of 4.3%.[2] On the genomic level, GBM is characterized by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) amplifications (40% of cases) and/or overexpression (60%), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutations (30%), tumor protein 53 (TP53) mutations (30%), mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) amplifications (<10%) and/ or overexpression (50%), p16INK4a deletions (30–40%), and loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 10 in 50–80% of all cases.[3] Around 5–10% of all GBMs harbor isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations with a better prognosis compared to tumors carrying the wildtype form known to exhibit a much more aggressive clinical behavior, particularly in adults.[4,5] It is now appreciated that IDH-wildtype and IDH-mutant gliomas represent distinct clinical and genetic entities, and efforts have been made to restrict the term “glioblastoma” to tumors without IDH mutations.[6,7] The standard-of-care treatment consists of maximal surgical resection of the tumor in combination with radiation and temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy. However, GBM is insidious and treatments have not been effective in preventing eventual disease progression as recurrence remains inevitable.[8–11]

Transcriptomic, genomic, and epigenomic characterization have unveiled the highly heterogeneous nature of GBM with complex interactions among different cells within as well as cells surrounding the tumor.[3,12–17] Comprehensive longitudinal analyses of the tumor transcriptome have uncovered intricate intertumoral heterogeneity and classified GBM into three distinct subtypes: classical (CL), proneural (PN), and mesenchymal (MES).[18] In addition to this intertumoral heterogeneity, single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrated the presence of numerous transcriptome subtypes within the same tumor.[14] Further, single-cell lineage tracking and expression analysis of specimens from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed that malignant cells in GBM exist in four main cellular states: neural-progenitor-like, oligodendrocyte-progenitor-like, astrocyte-like, and mesenchymal-like.[19] The number and frequency of cells in each defined state varies between patients and is influenced by mutations in the neurofibromin 1 (NF1) locus and copy number amplifications of EGFR, cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) loci.

The intricate combination of inter- as well as intratumoral heterogeneity plays a key role in rendering conventional and experimental targeted therapy approaches ultimately ineffective.[20–22] The majority of glioma cells lack the capacity to recapitulate a phenocopy of the original tumor and only a small subpopulation of neural stem-like cells within the tumor, called glioma stem cells (GSCs) or tumor initiating cells, have that ability upon xenotransplantation in immunocompromised mice.[23–25] Evidence suggests that these GSCs act as a driving factor in the development of chemo- and radio-resistance via upregulation/activation of pathways involved in DNA damage response and/or repair.[26,27] MES GSCs exhibit a more aggressive phenotype with increased therapeutic resistance.[28,29] Similar to the well-characterized epithelial–mesenchymal transition, PN GSCs can shift their molecular and phenotypic subtype toward a more MES-like state, thereby acquiring more aggressive characteristics leading to therapeutic resistance.[30] Interestingly, exposing PN GSCs to radiation therapy can downregulate PN associated markers while upregulating MES specific markers.[31] The exact course and mechanisms responsible for gliomagenesis remain opaque. Recent evidence suggests that astrocyte-like neural stem cells in the subventricular zone are the cells of origin that contain the driver mutations of GBM.[32]

1.2. Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

In the past, communication between tumor cells was thought to occur via the tumor secretome (soluble molecules) and cell-to-cell contact through gap junctions. The scientific community has since embraced another critical component of tumor communication that involves proteins and nucleic acids contained within extracellular vesicles, small nanoparticles shed by nearly every cell of the body.[33,34] EVs are highly heterogeneous and can be roughly divided into two main categories based on their mode of biogenesis: microvesicles and exosomes.[35] Microvesicles are generated by the outward budding of membrane vesicles from the cell surface whereas exosomes originate within the endosomal system.[36] In this review, we will collectively refer to them as EVs, as there is no reliable method or marker to distinguish one from the other. An important finding with broad relevance in biology, and certainly in the context of cancer, was the demonstration that EVs released by mast cells contain functional RNA and that exosomal mRNA can be transferred and translated into functional proteins after entering recipient cells.[37] Subsequent studies showed that EVs contain additional active molecules such as microRNA, long noncoding RNA, DNA, lipids, and proteins.[35,38,39] Following these initial findings, a plethora of studies demonstrated that EVs can functionally transfer biomolecules between a multitude of different cell types and may be used as a biomarker source or even be modified to act as therapeutic vehicles/agents.[37–52]

1.3. EVs and Intratumoral Heterogeneity

GBM remains incurable and resistant to chemo and targeted therapies, making it almost always fatal. Molecular classification into distinct subgroups has helped to shine light on GBM inter/intratumoral heterogeneity and demonstrated that these subgroups are flexible and differ spatially and temporally within patient tumors.[14,18,19,31] As a result, science begun to portray tumor growth as a Darwinian tree with the trunk harboring the founding ubiquitous driver mutations and the branches representing heterogeneous mutations not present in every tumor cell/tumor region.[53] The resulting intratumoral heterogeneity seems to contribute to, if not plays a major role, in the dismal GBM disease course by initiating phenotypic diversity and assisting the emergence of drug resistance. Single cell-derived GBM subclones, for example, showed distinct genetic identities and abilities to maintain differential drug resistance profiles.[54] Coactivation of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) like EGFR, C-MET and PDGFR in GBM may further explain the modest success of targeted therapies that inhibit individual RTKs.[55] Interestingly, a potential intratumoral heterogenic response to RTK is also observed in GBM; Szerlip et al. demonstrated the presence of heterogeneous amplification of EGFR and PDGFRA within the same tumor.[56] The temporal aspect of intratumoral heterogeneity is another crucial driver of GBM therapeutic resistance. For instance, PN GSCs have the ability to acquire treatment resistance and present a more aggressive phenotype by shifting toward a more mesenchymal state, similar to the well-described epithelial–mesenchymal transition in tumors of epithelial origin.[29–31]

Another reason for the opaque and aggressive nature of GBM is its spatial heterogeneity. Sampling of geographically distinct regions of the same tumor revealed tumor fragments with different GBM molecular subtypes.[57] Specific types of GSCs can exist in the GBM core in comparison to its invasive edge.[31] Interestingly, tumor cells at the invasive edge undergoing radiation treatment can acquire the expression of CD109 while losing CD133, which in turn drives oncogenic signaling resulting in increased radioresistance.[31]

A multitude of studies have demonstrated the profound role of EVs in modulating various cancers.[58] Early findings showed that EVs derived from different mesenchymal stem cells isolated from bone marrow, umbilical cord, and adipose tissue have various effects on recipient GBM (U87MG) cells, with adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cell EVs increasing cell proliferation, while bone marrow and umbilical cord cells having the reverse effect.[59] Further, intercellular transfer between tumor cells of the truncated and oncogenic form of EGFR (EGFRvIII; common in GBMs) via EVs has been demonstrated.[60] EVs containing EGFRvIII are released to cellular surroundings, fuse with plasma membranes of cancer cells lacking this receptor, leading to altered oncogenic activity in recipient cells. This process can include activation of transforming signaling pathways, changes in expression of EGFRvIII-regulated genes, morphological transformation, and increase in anchorage-independent growth capacity, demonstrating the phenotype transforming ability of EVs among subsets of GBM cells. Interestingly, EVs isolated from GBM cells promoted proliferation and migration of recipient astrocytoma (SHG-44) cells.[61] Pinet et al. demonstrated that exposing TrkB-containing EVs to YKL-40-silenced cells restored cell proliferation and promoted endothelial cell activation.[62] In addition, TrkB-depleted EVs derived from YKL-40-silenced cells inhibited tumor growth in vivo.[62] Zeng et al. showed that EVs derived from GBM cells harboring PTPRZ1–MET fusion were taken up by nonharboring GBM cells and normal human astrocytes, resulting in altered gene expression, migration, invasion, neurosphere growth, angiogenesis, as well as TMZ resistance.[63] In TMZ-resistant MES tumors, a consistent diminution of mesenchymal features correlated with increased expression of Nestin, leading to a decreased sensitivity to radiation.[64] Interestingly, mRNA expression profile corresponding to GSC phenotype and TMZ resistance were mirrored in the transcriptome of corresponding EVs.[64] Another study conducted by Ricklefs et al. showed that EV-mediated protein transfer between MES and PN cells leads to increased protumorigenic behaviors, demonstrating the ability of EVs to maintain and modulate intratumoral heterogeneity in high grade gliomas.[65] Although EV signatures were heterogeneous, they reflected the molecular makeup of their donor GSCs and consistently clustered into the two molecular subtypes. Further, analyses of high-grade glioma patient data from the TCGA database revealed that proneural tumors with mesenchymal EV signatures or mesenchymal tumors with proneural EV signatures were both associated with worse outcomes, suggesting influences by the proportion of tumor cells of varying subtypes in tumors.[65] Recently, we showed that MES GSCs release EVs which can be taken up by PN cells, leading to an increase in their invasiveness, stemness, migration, proliferation, aggressiveness, and therapeutic resistance through nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT3) signaling.[66] Our study endorses the role of extracellular vesicles in intratumoral heterogeneity and therapeutic resistance in GBM. Gyuris et al. showed that mRNA from medium-sized glioma EVs (0.22–0.79 μm) most closely reflects the cellular transcriptome, whereas RNA from the small EV fraction (0.21–0.02 μm) is enriched with small noncoding RNAs, highlighting the highly heterogeneous composition of GBM-derived EVs.[67] Interestingly, small EVs appear to be less heterogeneous in their protein content compared to their larger counterparts.

1.4. EVs and the Tumor Microenvironment

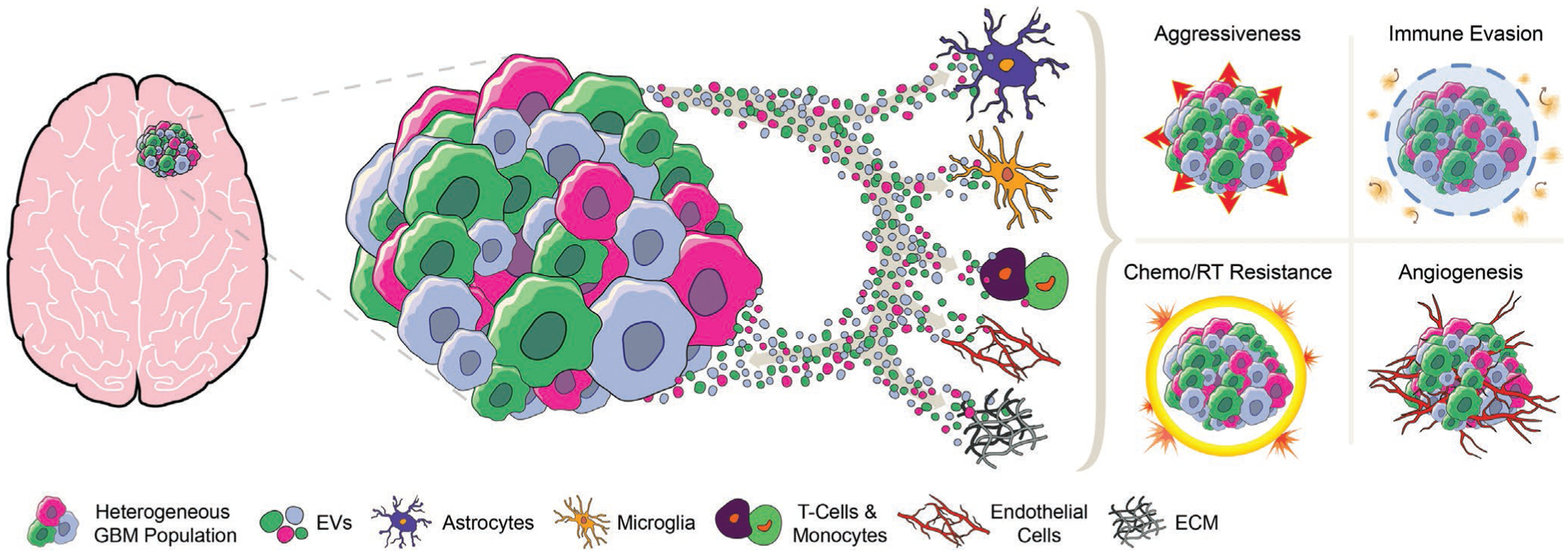

In addition to their role in tumor–tumor cell interaction, EVs appear to play a crucial role in the communication between tumor cells and their surrounding microenvironment (Figure 1). The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a network of various cell types that actively contributes to cancer initiation and consequential progression, and nearly all hallmarks of cancer biology.[68,69] The TME usually consists of myofibroblasts, fibroblasts, neuroendocrine cells, adipose cells, immune-inflammatory cells, the extracellular matrix, components of the cardiovascular system as well as lymphatic vascular networks.[70] Apart from the juxtracrine signaling present in the tumor environment, EVs have been shown to contribute to paracrine interactions between cells in the TME. Nearly every component of the TME appears to receive signals from the tumor via EVs which thereby modulate the complex interactions of tumor and nontumor cells. EVs derived from breast cancer cells, for example, can instigate nontumorigenic epithelial cells to form tumors.[45] In the context of brain cancer, EVs have been shown to facilitate communication between GBM and astrocytes.[71,72] For instance, GBM cell derived EVs stimulate normal astrocytes to acquire a tumor-supportive phenotype (through p53 and MYC signaling pathways).[73] Furthermore, astrocytes treated with GBM-derived EVs displayed enhanced cytokine production and increased migratory capacity, promoting tumor growth.[74] Similarly, glioma-derived EVs shuttle lncRNA activated by TGF-β (lncRNA-ATB) to astrocytes, increasing their activation.[75] More importantly, astrocytes activated by lncRNA-ATB in turn induce the invasion and migration of glioma cells.[75] Similar to what has been observed in other cancers, GBM EVs have the ability to regulate an intricate tumor suppression signaling network in order to modulate the TME.[76] Gao et al. demonstrated that gliomas communicate with nonglioma cells in the TME (including glial cells, neurons, and vascular cells) and that inhibition of EV release results in halting tumor growth.[77]

Figure 1.

Illustration highlighting the core interaction of extracellular vesicles (EVs) secreted by glioblastoma (GBM) cells. GBM-derived EVs exert effects on astrocytes, microglia, T-cells, monocytes, endothelial cells, and components of the extracellular matrix. Further, EV exchange between different GBM cell subpopulations supports intratumoral heterogeneity. Consequently, GBM-derived EVs facilitate tumor pathogenesis by increasing aggressiveness and invasion ability, supporting immune evasion, modulating therapeutic resistance, and promoting angiogenesis. GBM = glioblastoma; EVs = extracellular vesicles; ECM = extracellular matrix; Chemo = chemotherapy; RT = radiotherapy.

Complex interactions between immune cells and tumor cells lead to both inhibitory as well as stimulatory effect on tumor growth and progression.[78,79] The immune environment in the brain significantly differs from the peripheral immune system. Main components of the neuroimmune and brain tumor environment are astrocytes, microglia, infiltrating macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils.[80] The immunomodulatory potential and immune evasion ability of EVs has been extensively described in various cancers.[81–86] Early findings identified selective enrichment of proteins involved in recruitment of leukocytes in EVs isolated from GBM cultures.[87] Furthermore, EVs from murine GL261 glioma cells have shown to promote tumor growth by inhibiting CD8+ T-cells.[88] More recently, van der Vos et al. demonstrated that GBM-derived EVs transfer functional RNA to microglia/macrophages in the brain. Exposure of microglia to GBM-EVs lead to downregulation of miR-21/miR-451 target c-Myc mRNA.[89] Abels et al. revealed that GBM EVs functionally transfer miR21, thereby reprogramming microglia to create a favorable tumor microenvironment.[40] Another strategy by which GBM could modulate the TME and evade immune response is to increase the release of PD-L1 presenting EVs, thereby blocking T-cell activation and proliferation. A strong correlation was found between PD-L1 DNA in circulating EVs from GBM patients and tumor volume, indicating potential applications of EVs as a biomarker source.[90] Interestingly, Hellwinkel et al. demonstrated that high concentrations of glioma-derived EVs decrease peripheral blood mononuclear cell/T-cell activation.[91] Domenis et al. suggested that glioma-derived EVs suppress T cell immune response indirectly by acting on monocyte maturation.[92] Furthermore, functional mRNA transfer between GBM cells and Gr1+ CD11b+ myeloid-derived suppressor cell population has been observed.[93]

Pathological angiogenesis is another hallmark of cancer and essential for extensive tumor growth.[68,94] GBM is the most vascularized and angiogenic of all solid tumors.[95] GBMs often express a multitude of proangiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), PDGF, fibroblast growth factor, integrins, and angiopoietins.[96,97] Therefore, signal exchange between tumor and endothelial cells is crucial in GBM angiogenesis.[98,99] EVs have been shown to play a major role in this bidirectional crosstalk in various types of cancer.[100–104] Skog et al. showed in their landmark paper that GBM derived EVs do not just transport RNA and protein but are further loaded with angiogenic proteins and ultimately stimulate an angiogenic phenotype in normal human brain microvascular endothelial cells.[105] Notably, GBM EVs contain a variety of functional angiogenic proteins[106–109] and RNAs[110–112] modulating the endothelial components of the TME. Human GBM cell line U251 derived EVs are capable of stimulating proliferation, motility, and tube formation of endothelial cells in vitro.[106] Furthermore, Treps et al. reported that EVs isolated from patient-derived GSCs contain the proangiogenic propermeability factor VEGF-A and interact with brain endothelial cells, impacting their ability to form new vessels.[108] It is worth mentioning that EVs derived from GBM cells under hypoxic conditions can induce angiogenesis in vitro and ex vivo through modulation of endothelial cells.[107] Despite all of these exciting results, it is not yet fully understood how EVs transporting a VEGF ligand would activate the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) on the endothelial surface to elicit angiogenic signaling. Furthermore, bevacizumab (a VEGF neutralizing antibody) could not produce notable survival benefits in GBM patients.[113,114] These findings may indicate that VEGF-driven angiogenesis (and VEGF-transporting/modulating EVs) play a negligible role in GBM neovascularization.

Indirect evidence further supports the potential signal exchange between the extracellular matrix and GBM cells, as extensively reviewed in Morad et al.[115–117]

2. EVs and Therapeutic Resistance

GBMs are notorious for their ability to evade therapeutic treatment and develop resistance. Standard of care consists of maximal safe surgical resection followed by a combination of TMZ and radiation therapy.[9] However, long-term survival remains uncommon and advances in developing new treatment strategies have been perpetually accompanied by disappointment. Various factors render GBM a difficult tumor to treat and practically incurable. In addition to GBMs inter/intratumoral heterogeneity, the bidirectional crosstalk of GSCs with the TME facilitates GBM to decrease/inactivate drug uptake or activate a multitude of repair mechanisms to render drug-induced damage inefficient.[22,66] Compelling evidence suggests that EVs add yet another facet to the GBM treatment evasion mechanism repertoire. GBM EVs appear to counteract therapeutic approaches in a more direct manner. Early findings identified that mRNA and proteins in GBM EVs can act as surrogate biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis, hinting at a potential causal effect between EVs and treatment outcome.[118,119] More recent studies suggested that EVs derived from GBM cells harboring the PTPRZ1–MET fusion transcript lead to TMZ resistant phenotype in recipient nonfusion GBM cells.[63] Interestingly, treatment of GBM cells with their own EVs also induces TMZ resistance.[120] Of note, blood from GBM patients contains a higher number of circulating EVs and the release of EVs is enhanced in resistant tumors previously challenged with TMZ.[121] Mass spectrometry and in silico analysis further suggest that EVs derived from TMZ-treated cells are enriched with proteins related to cell adhesion.[121] Zhang et al. reported that the lncRNA SET-binding factor 2 antisense RNA1 (lncSBF2-AS1) is upregulated in TMZ-resistant GBM cells and tissues, and inhibiting it regains sensitivity to this chemotherapeutic agent.[122] Interestingly, EVs derived from TMZ-resistant GBM cells had increased levels of lncSBF2-AS1 and lead to TMZ resistance in recipient GBM cells.[122] Furthermore, poor response of GBM patients to TMZ was associated with increased lncSBF2-AS1 in serum-derived EVs.[122] Yin et al. found that TMZ resistance correlates with miR-1238 levels in serum and GBM cell-derived EVs, and these EVs confer chemoresistance in recipient cells.[123] Radioresistant GBM cells or cells exposed to radiation exhibit an upregulation of the antisense transcript of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (AHIF).[124] Interestingly, EVs derived from AHIF-knockdown GBM cells inhibited viability, invasion, and radioresistance, whereas EVs derived from AHIF-overexpressing GBM cells had the reverse effect in recipient cells. Further, AHIF regulates factors associated with angiogenesis and migration in EVs, concluding that AHIF promotes GBM progression and radioresistance via EVs. GBMs tend to shift toward a more aggressive and resistant phenotype following treatment. Pavlyukov et al. hypothesized that EVs released from apoptotic GBM cells (apoEVs) could change the behavior of surviving tumor cells and demonstrated that GBM cells exposed to apoEVs had an increased TMZ, cisplatin, and radiation resistance.[125] They concluded that apoEVs alter RNA splicing in recipient cells (identifying RBM11 as a representative splicing factor shed in EVs upon apoptosis), thereby promoting a highly migratory and therapeutic resistant phenotype.

A novel mechanism by which GBM utilizes EVs to counteract therapeutic attacks was recently described by Simon et al.[126] The authors showed that bevacizumab can be directly captured by GBM cells and is detectable at the surface of their corresponding EVs. Interestingly, inhibiting the production of EVs improved the antitumor effect of bevacizumab, suggesting that GBM may utilize EVs to decrease bevacizumab efficacy.

Overwhelming evidence suggests a crucial role of EVs in GBM pathogenesis and progression; however, a definite proof that EV signaling is essential for GBM progression and, if inhibited, would disable the disease-driving mechanisms, remains to be established.

3. EV Tracking

To understand EV biogenesis and their role in tumorigenesis, it is essential to develop sensitive tools to image their release and uptake by different cells. EVs tracking poses significant technical challenge owing to their size, diversity of cargo content, and heterogeneity of biogenesis.[35] Various methods have been developed to track EVs, characterize their biodistribution, and to monitor successful functional cargo delivery.

3.1. Direct Tracking Methods

EVs can be directly labeled by means of various agents like lipophilic tracer dyes, radionuclides, or magnetic particles to allow subsequent tracking in vitro and in vivo. One of the simplest strategies to image and track EVs is to label the EV lipid membrane with a lipophilic tracer dye. Many studies have used dyes like DiR,[127–129] DiD,[130,131] PKH26,[132] or PKH67[133] to visualize EV uptake and/or biodistribution. Although this method is simple, it suffers from major disadvantages; for instance, non-EV nanoparticles are formed during the dye staining process, which may potentially lead to confounding signals.[134,135] Further, these dyes have a long in vivo half-life (5 to >100 days), thus while they may assist in “marking a trail” of where the administered EVs have been trafficked to, the persistence of the dye may outlast the labeled EVs, yielding an inaccurate spatiotemporal information.[136] In a newer study, Mondal et al. demonstrated the visualization and tracking of EVs derived from glioma cells by labeling intravesicular proteins, such as TSG101 or HSP70, thereby avoiding noise resulting from mislabeling.[137] However, this dye-based EV labeling also comes with the downside that dye can be released from EVs, leading to false signals. In addition, the use of tracer dyes has not yet been demonstrated to be suitable for in vivo tracking.

Another way of directly labeling and tracking EVs, especially for deep organs/tissues, is based on nuclear imaging. Early studies used 99mTc-hexamethylpropyleneamineoxime (HMPAO) to label EVs and monitor their biodistribution pattern.[127,138] Although EVs are easily visualized by a gamma camera or SPECT, the low radiochemical yield might pose imaging problems at low EV concentrations. Another approach uses the 99mTc-tricarbonyl complex to achieve a higher labeling efficiency (~40%) in EVs.[139] Morishita et al. conjugated a streptavidin–lactadherin fusion protein expressed in EVs with a 125I-labeled biotin derivative to obtain radioiodine-labeled EVs and quantify biodistribution.[140]

More recent studies show that EVs can be labeled with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) and consequently visualized by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[141,142] Although suitable for in vivo imaging, a large number of EVs is required for this technique and the sensitivity of USPIO-labeled EVs is significantly lower than that of nuclear or optical imaging.[143]

3.2. Indirect Tracking Methods

For indirect tracking methods, cells are genetically modified to express reporter proteins, which are taken up by EVs released from these cells. Bioluminescence imaging via luciferases has long been used to monitor biological processes in vitro and in vivo due to assay simplicity and sensitivity.[144,145] We have demonstrated that by engineering the cell surface to express a fusion protein between Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) and a biotin acceptor domain, the released EV membranes are labeled with Gluc and biotin (GlucB).[136,146] This EV reporter allows multimodal imaging (bioluminescence and fluorescence using streptavidin-conjugated dyes) of EV biodistribution and uptake by different organs in vivo. Subsequent studies showed that membrane-bound Gluc may undergo proteolytic cleavage, leading to the release of protein fragments into the extracellular space in an active form.[147] Following this observation, we developed a novel membrane-bound Gluc based assay to quantitatively track the shedding of membrane proteins from EVs in vitro and in vivo.[147] Furthermore, we utilized this assay to demonstrate that ectodomain shedding in EVs is continuous and mediated by proteases.[147] Takahashi et al. took another approach and used lacadherin, a membrane-associated protein often found in EVs, and designed a fusion protein between Gluc and a truncated form of this protein, which labeled cancer cells and their secreted EVs, allowing their in vivo visualization.[148]

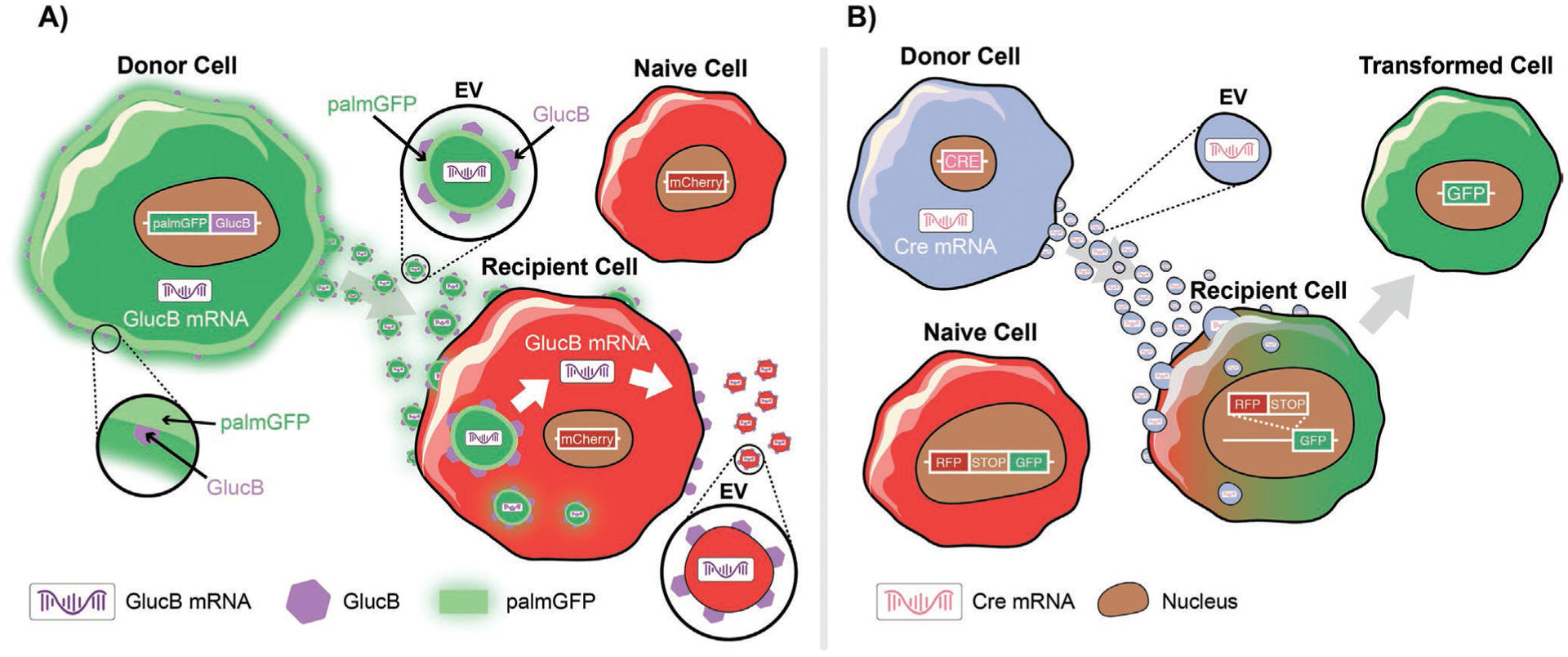

To monitor EV uptake at the cellular level, fluorescent-based techniques were developed by several groups. Suetsugu et al. tagged GFP to CD63, a general marker of EVs, and used this reporter to monitor transfer of EVs from breast cancer cells into the TME.[149] Another study tagged GFP to CD9 or RFP to miR-214 to monitor exosomal trafficking between hepatic cells.[150] We took a different approach and fused GFP or tdTomato to a palmitoylation signal (PalmGFP or PalmtdTomato), thereby labeling the cell membrane and consequently EVs secreted by them (Figure 2A).[136,146] We used these reporters to monitor EV exchange between different tumor cells and their microenvironment. More recently, Hyenne et al. described an approach for tracking circulating tumor EVs in a living zebrafish by combining chemical and genetically encoded probes.[151] The authors used this strategy to provide a detailed description of EV dynamics and uptake properties in a living system. Furthermore, they showed that tumor EVs can activate macrophages, demonstrating the usefulness of this model system to track EVs and dissect their role in tumor progression and metastatic niche formation in vivo.[151]

Figure 2.

Approaches to track/visualize EV uptake or cargo transfer. A) Schematic of a GlucB (Gluc fused to a biotin acceptor domain) bioluminescent reporter multiplexed with palmitoylated GFP (palmGFP) to monitor EV uptake and mRNA translation in recipient mCherry cells. Recipient cells express palmGFP and translate EV-delivered GlucB mRNA. B) Cre-LoxP system to monitor functional release of EV content in recipient cells. Schematic depiction of a red-to-green color switch upon transfer of EVs from Cre+ donor cells to recipient cells.

3.3. Functional Transfer of EV Content

All of the above discussed techniques have proven to be valuable tools to visualize/identify EV exchange with different cells and monitor their biodistribution. They, however, lack the ability to track and/or confirm functional transfer of proteins or nucleic acids via EVs. As every cell is releasing EVs, identifying cargo transfer between specific cells of interest poses technical challenges, especially in vivo. To monitor EV-RNA cargo, we tagged transcripts encoding PalmtdTomato with MS2 RNA binding sequences, which could be detected by co-expression of bacteriophage MS2 coat protein fused to GFP. By multiplexing these fluorescent reporters with the GlucB bioluminescent EV membrane reporter, we revealed the rapid dynamics of both EV uptake and translation of EV-delivered cargo mRNAs in cancer cells, which occurred within 1 h posthorizontal transfer between cells (Figure 2A).[146] A different approach utilized the Cre-LoxP system, in which cells are engineered to secrete EVs containing Cre mRNA, which in turn induces recombination in neurons after injection into the brain.[152] Using this system, the authors demonstrated that recombined neurons exhibit a different miRNA profile compared to their nonrecombined counterparts. More recently, Zomer et al. used the Cre-LoxP system to demonstrate the uptake and functional release of EV content in recipient tumor cells (in the local environment and at distant sites).[41] Here, recipient cells were modified to express a reporter which can shift from DsRed to GFP upon functional transfer of Cre-recombinase via EVs (Figure 2B). As a result, only cells that have taken up and processed Cre+ EVs will express GFP and appear green. Using this approach, the authors showed that mRNA containing EVs released by malignant tumor cells are taken up and are functionally processed by less malignant tumor cells located within close proximity and at distant tumor sites, resulting in modulation of their behavior. All of these studies successfully demonstrate functional transport of RNA between cells via EVs, and that this RNA is transported and processed in recipient cells. Additional studies and approaches are needed to evaluate the exclusive uptake of EV-contained proteins (without RNA) and their contribution to the observed effect in recipient cells.

4. Where to Go from Here?

The last decade has observed a remarkable progress in the field of EVs. Many findings highlight the “power” of EVs in modulating recipient cells and their role in cancer initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance. However, many questions remain unaddressed. For instance, how long does the observed EV-mediated effect last and is it reversible? Studies are needed to investigate whether EVs induce stable effects and transformations and/or temporary phenotypic switches in recipient cells. Transfer of proteins may transiently modulate a cell’s phenotype, whereas exchange of mRNA, miRNA, DNA and/or transcription factors may lead to permanent reprogramming. One important point to keep in mind is that tumor cells constantly release EVs and their exerted effect is therefore likely to be long-term. However, there is no definite proof yet that GBM is a scene of horizontal transformation mediated by EV communication between cancer and normal cells. These studies clearly demonstrate surrogate changes in cell growth, invasion ability, and aggressiveness of recipient cells, but fail to rule out the possibility that the observed effect may simply be transient.

EVs have been shown to increase metastatic potential of cells via distant communication.[41] Long-distance effects of GBM EVs, however, are yet to be described. Future studies could evaluate if this potential mechanism of long-distance signaling may offer additional answers to the recurring nature of GBM. Circulating tumor cells, enriched with MES genotype/phenotype, were recently described in blood of GBM patients.[153,154] Interestingly, GBM EVs can be detected in blood or cerebrospinal fluid and may function as a platform for “liquid biopsy” approaches not only for GBM, but for any cancer type;[155] however, separating tumor-derived EVs from the overwhelming number of “normal” EVs remains incredibly difficult. New approaches are necessary to tackle this “needle in the haystack” problem and identification of tumor EV-specific markers could help in this process.

Another major question that needs to be addressed is how to separate the EV-mediated effect from other secreted molecules on recipient cells. It is simple to extract EVs or other soluble factors using size exclusion or ultracentrifugation methods in an in vitro setting, however, this is practically impossible in vivo. Some studies used drugs/inhibitors to disrupt EV formation or release in order to establish a causal link between EVs and target effect.[126,156,157] New approaches that may physically encapsulate cells (for instance hydrogels with different pore sizes compatible with in vivo use) to either inhibit EV release to the environment but allow for smaller proteins to pass through, or allow secretion of both EVs and soluble proteins, could solve this issue.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing shed light on many important processes in tumor heterogeneity, development, and therapeutic resistance. Although challenging, novel techniques that allow analyses at the single EV level will further help to fill in important gaps in our understanding of the role of EVs in cancer in general and GBM in particular. Various approaches for single EV characterization have been developed and some of which confirmed the relationship between GBM and EVs.[119,158,159] However, only a limited number of targets could be analyzed simultaneously with each of these techniques. Increasing the output and sensitivity of these methods may help to not only understand the role of EVs in cancer, but to also develop methods to improve blood-based diagnostics and to predict prognosis and therapeutic response in real-time.

GBM utilizes EVs in numerous ways to manipulate its environment and evade treatment. The discovery of EVs and their role in GBM pathology, however, has opened doors to a whole new world of therapeutic approaches, giving hope to finding an effective treatment for this aggressive cancer.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute 2P01CA069246 (BAT/AC), and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke 2R01NS064983 (BAT).

Biographies

Markus W. Schweiger received his M.Sc. degree from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the course of the Neurasmus program (A European Master in Neuroscience). He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. at the Massachusetts General Hospital and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam working on the role of extracellular vesicles in glioblastoma progression and treatment resistance.

Bakhos A. Tannous is an associate professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Experimental Therapeutics and Molecular Imaging Unit at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. His research interest is to understand the mechanisms underlying malignant brain tumor progression and therapeutic resistance, and to develop novel drug/gene/cell therapeutic strategies against these tumors.

Footnotes

The ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under https://doi.org/10.1002/adbi.202000035.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Markus W. Schweiger, Experimental Therapeutics and Molecular Imaging Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Neuro-Oncology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02129, USA Neuroscience Program, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02129, USA; Department of Neurosurgery, Cancer Center Amsterdam, Brain Tumor Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam HV 1081, The Netherlands.

Bakhos A. Tannous, Experimental Therapeutics and Molecular Imaging Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Neuro-Oncology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02129, USA Neuroscience Program, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02129, USA.

References

- [1].Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J, Liu M, Blanda R, Kromer C, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Neuro Oncol. 2015, 17, iv1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, iv1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JCH, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Siu IM, Gallia GL, Olivi A, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Keir S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Busam DA, Tekleab H, Diaz LA, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Strausberg RL, Marie SKN, Shinjo SMO, Yan H, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Karchin R, Papadopoulos N, Parmigiani G, et al. , Science 2008, 321, 1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Suzuki H, Aoki K, Chiba K, Sato Y, Shiozawa Y, Shiraishi Y, Shimamura T, Niida A, Motomura K, Ohka F, Yamamoto T, Tanahashi K, Ranjit M, Wakabayashi T, Yoshizato T, Kataoka K, Yoshida K, Nagata Y, Sato-Otsubo A, Tanaka H, Sanada M, Kondo Y, Nakamura H, Mizoguchi M, Abe T, Muragaki Y, Watanabe R, Ito I, Miyano S, Natsume A, et al. , Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 47, 458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gagné LM, Boulay K, Topisirovic I, Huot MÉ, Mallette FA, Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brat DJ, Aldape K, Colman H, Figrarella-Branger D, Fuller GN, Giannini C, Holland EC, Jenkins RB, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B, Komori T, Kros JM, Louis DN, McLean C, Perry A, Reifenberger G, Sarkar C, Stupp R, van den Bent MJ, von Deimling A, Weller M, Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 139, 603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, Alexander BA, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Barthel FP, Batchelor TT, Bindra RS, Chang SM, Chiocca EA, Cloughesy TF, DeGroot JF, Galanis E, Gilbert MR, Hegi ME, Horbinski C, Huang RY, Lassman AB, Le Rhun E, Lim M, Mehta MP, Mellinghoff IK, Minniti G, Nathanson D, Platten M, Preusser M, Roth P, Sanson M, Schiff D, Short SC, et al. , Neuro Oncol. 2020, 22, 1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ramirez YP, Weatherbee JL, Wheelhouse RT, Ross AH, Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJB, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO, N. Engl. J. Med 2005, 352, 987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, Taphoorn M, Sahm F, Harting I, Brandes AA, Taal W, Domont J, Idbaih A, Campone M, Clement PM, Stupp R, Fabbro M, Le Rhun E, Dubois F, Weller M, von Deimling A, Golfinopoulos V, Bromberg JC, Platten M, Klein M, van den Bent MJ, N. Engl. J. Med 2017, 377, 1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fernandes C, Costa A, Osório L, Lago RC, Paulo L, Bruno C, Cláudia C, Glioblastoma, Codon Publications, Brisbane: 2017, pp. 197–241. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Verhaak RGW, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, Miller CR, Ding L, Golub T, Mesirov JP, Alexe G, Lawrence M, O’Kelly M, Tamayo P, Weir BA, Gabriel S, Winckler W, Gupta S, Jakkula L, Feiler HS, Hodgson JG, James CD, Sarkaria JN, Brennan C, Kahn A, Spellman PT, Wilson RK, Speed TP, Gray JW, Meyerson M, et al. , Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McLendon R, Friedman A, Bigner D, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ, Mastrogianakis GM, Olson JJ, Mikkelsen T, Lehman N, Aldape K, Yung WKA, Bogler O, Weinstein JN, VandenBerg S, Berger M, Prados M, Muzny D, Morgan M, Scherer S, Sabo A, Nazareth L, Lewis L, Hall O, Zhu Y, Ren Y, Alvi O, Yao J, Hawes A, Jhangiani S, Fowler G, et al. , Nature 2008, 455, 1061.18772890 [Google Scholar]

- [14].Patel AP, Tirosh IP, Trombetta JJ, Shalek AK, Gillespie SM, Wakimoto H, Cahill DP, Nahed BV, Curry WT, Martuza RL, Louis DN, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Suva ML, Regev A, Bernstein BE, Suvà ML, Regev A, Bernstein BE, Science 2014, 344, 1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, Zheng S, Chakravarty D, Sanborn JZ, Berman SH, Beroukhim R, Bernard B, Wu C-J, Genovese G, Shmulevich I, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Zou L, Vegesna R, Shukla SA, Ciriello G, Yung WKA, Zhang W, Sougnez C, Mikkelsen T, Aldape K, Bigner DD, Van Meir EG, Prados M, Sloan AE, Black KL, et al. , Cell 2013, 155, 462.24120142 [Google Scholar]

- [16].Melin BS, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Wrensch MR, Johansen C, Il’yasova D, Kinnersley B, Ostrom QT, Labreche K, Chen Y, Armstrong G, Liu Y, Eckel-Passow JE, Decker PA, Labussière M, Idbaih A, Hoang-Xuan K, Di Stefano AL, Mokhtari K, Delattre JY, Broderick P, Galan P, Gousias K, Schramm J, Schoemaker MJ, Fleming SJ, Herms S, Heilmann S, Nöthen MM, Wichmann HE, Schreiber S, et al. , Nat. Genet 2017, 49, 789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pangeni RP, Zhang Z, Alvarez AA, Wan X, Sastry N, Lu S, Shi T, Huang T, Lei CX, James CD, Kessler JA, Brennan CW, Nakano I, Lu X, Hu B, Zhang W, Cheng SY, Epigenetics 2018, 13, 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang Q, Hu B, Hu X, Kim H, Squatrito M, Scarpace L, DeCarvalho AC, Lyu S, Li P, Li Y, Barthel F, Cho HJ, Lin Y-H, Satani N, Martinez-Ledesma E, Zheng S, Chang E, Sauvé C-EG, Olar A, Lan ZD, Finocchiaro G, Phillips JJ, Berger MS, Gabrusiewicz KR, Wang G, Eskilsson E, Hu J, Mikkelsen T, DePinho RA, Muller F, et al. , Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Neftel C, Laffy J, Filbin MG, Hara T, Shore ME, Rahme GJ, Richman AR, Silverbush D, Shaw ML, Hebert CM, Dewitt J, Gritsch S, Perez EM, Gonzalez Castro LN, Lan X, Druck N, Rodman C, Dionne D, Kaplan A, Bertalan MS, Small J, Pelton K, Becker S, Bonal D, De Nguyen Q, Servis RL, Fung JM, Mylvaganam R, Mayr L, Gojo J, et al. , Cell 2019, 178, 835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Parker JJ, Canoll P, Niswander L, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Foshay K, Waziri A, Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 18002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Parker NR, Khong P, Parkinson JF, Howell VM, Wheeler HR, Front. Oncol 2015, 5, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Qazi MA, Vora P, Venugopal C, Sidhu SS, Moffat J, Swanton C, Singh SK, Ann. Oncol 2017, 28, 1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patrizii M, Bartucci M, Pine SR, Sabaawy HE, Front. Oncol 2018, 8, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB, Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 5821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].da Hora CC, Schweiger MW, Wurdinger T, Tannous BA, Cells 2019, 8, 1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, Dewhirst MW, Bigner DD, Rich JN, Nature 2006, 444, 756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, Parada LF, Nature 2012, 488, 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bhat KPLL, Balasubramaniyan V, Vaillant B, Ezhilarasan R, Hummelink K, Hollingsworth F, Wani K, Heathcock L, James JD, Goodman LD, Conroy S, Long L, Lelic N, Wang S, Gumin J, Raj D, Kodama Y, Raghunathan A, Olar A, Joshi K, Pelloski CE, Heimberger A, Kim SH, Cahill DP, Rao G, DenDunnen WFA, Boddeke HWGMGM, Phillips HS, Nakano I, Lang FF, et al. , Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang M, Li P, Benos PV, Santana-Santos L, Luthra S, Li J, Hu BB, Cheng S-Y, Smith L, Nakano I, Sobol RW, Kim S-H, Chandran UR, Joshi K, Mao P, Joshi K, Li J, Kim S-H, Li P, Santana-Santos L, Luthra S, Chandran UR, Benos PV, Smith L, Wang M, Hu BB, Cheng S-Y, Sobol RW, Nakano I, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dongre A, Weinberg RA, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2019, 20, 69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Minata M, Audia A, Shi J, Lu S, Bernstock J, Pavlyukov MS, Das A, Kim SH, Shin YJ, Lee Y, Koo H, Snigdha K, Waghmare I, Guo X, Mohyeldin A, Gallego-Perez D, Wang J, Chen D, Cheng P, Mukheef F, Contreras M, Reyes JF, Vaillant B, Sulman EP, Cheng SY, Markert JM, Tannous BA, Lu X, Kango-Singh M, Lee LJ, et al. , Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lee JH, Lee JE, Kahng JY, Kim SH, Park JS, Yoon SJ, Um JY, Kim WK, Lee JK, Park J, Kim EH, Lee JH, Lee JH, Chung WS, Ju YS, Park SH, Chang JH, Kang SG, Lee JH, Nature 2018, 560, 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Katsuda T, Kosaka N, Ochiya T, Proteomics 2014, 14, 412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Becker A, Thakur BK, Weiss JM, Kim HS, Peinado H, Lyden D, Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Abels ER, Breakefield XO, Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 2016, 36, 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2018, 19, 213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO, Nat. Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zaborowski MP, Balaj L, Breakefield XO, Lai CP, Bioscience 2015, 65, 783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Maas SLN, Breakefield XO, Weaver AM, Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Abels ER, Maas SLN, Nieland L, Wei Z, Cheah PS, Tai E, Kolsteeg CJ, Dusoswa SA, Ting DT, Hickman S, El Khoury J, Krichevsky AM, Broekman MLD, Breakefield XO, Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zomer A, Maynard C, Verweij FJ, Kamermans A, Schäfer R, Beerling E, Schiffelers RM, De Wit E, Berenguer J, Ellenbroek SIJ, Wurdinger T, Pegtel DM, Van Rheenen J, Cell 2015, 161, 1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Barile L, Vassalli G, Pharmacol. Ther 2017, 174, 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Saadatpour L, Fadaee E, Fadaei S, Nassiri Mansour R, Mohammadi M, Mousavi SM, Goodarzi M, Verdi J, Mirzaei H, Cancer Gene Ther. 2016, 23, 415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Xu R, Rai A, Chen M, Suwakulsiri W, Greening DW, Simpson RJ, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2018, 15, 617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Melo SA, Sugimoto H, O’Connell JT, Kato N, Villanueva A, Vidal A, Qiu L, Vitkin E, Perelman LT, Melo CA, Lucci A, Ivan C, Calin GA, Kalluri R, Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Boelens MC, Wu TJ, Nabet BY, Xu B, Qiu Y, Yoon T, Azzam DJ, Twyman-Saint Victor C, Wiemann BZ, Ishwaran H, Ter Brugge PJ, Jonkers J, Slingerland J, Minn AJ, Cell 2014, 159, 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Luga V, Zhang L, Viloria-Petit AM, Ogunjimi AA, Inanlou MR, Chiu E, Buchanan M, Hosein AN, Basik M, Wrana JL, Cell 2012, 151, 1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cai Z, Yang F, Yu L, Yu Z, Jiang L, Wang Q, Yang Y, Wang L, Cao X, Wang J, J. Immunol 2012, 188, 5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Xin H, Li Y, Buller B, Katakowski M, Zhang Y, Wang X, Shang X, Zhang ZG, Chopp M, Stem Cells 2012, 30, 1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Felicetti F, De Feo A, Coscia C, Puglisi R, Pedini F, Pasquini L, Bellenghi M, Errico MC, Pagani E, Carè A, J. Transl. Med 2016, 14, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wiklander OPB, Brennan M, Lötvall J, Breakefield XO, Andaloussi SEL, Sci. Transl. Med 2019, 11, eaav8521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hall J, Prabhakar S, Balaj L, Lai CP, Cerione RA, Breakefield XO, Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 2016, 36, 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yap TA, Gerlinger M, Futreal PA, Pusztai L, Swanton C, Sci. Transl. Med 2012, 4, 127ps10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Reinartz R, Wang S, Kebir S, Silver DJ, Wieland A, Zheng T, Kupper M, Rauschenbach L, Fimmers R, Shepherd TM, Trageser D, Till A, Schafer N, Glas M, Hillmer AM, Cichon S, Smith AA, Pietsch T, Liu Y, Reynolds BA, Yachnis A, Pincus DW, Simon M, Brustle O, Steindler DA, Scheffler B, Clin. Cancer Res 2017, 23, 562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Stommel JM, Kimmelman AC, Ying H, Nabioullin R, Ponugoti AH, Wiedemeyer R, Stegh AH, Bradner JE, Ligon KL, Brennan C, Chin L, DePinho RA, Science 2007, 318, 287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Szerlip NJ, Pedraza A, Chakravarty D, Azim M, McGuire J, Fang Y, Ozawa T, Holland EC, Hused JT, Jhanwar S, Leversha MA, Mikkelseni T, Brennan CW, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sottoriva A, Spiteri I, Piccirillo SGM, Touloumis A, Collins VP, Marioni JC, Curtis C, Watts C, Tavaré S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Zomer A, Van Rheenen J, Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Del Fattore A, Luciano R, Saracino R, Battafarano G, Rizzo C, Pascucci L, Alessandri G, Pessina A, Perrotta A, Fierabracci A, Muraca M, Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 2015, 15, 495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, Lhotak V, May L, Guha A, Rak J, Nat. Cell Biol 2008, 10, 619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yang JK, Yang JP, Tong J, Jing SY, Fan B, Wang F, Sun GZ, Jiao BH, J. Neurooncol 2017, 131, 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Pinet S, Bessette B, Vedrenne N, Lacroix A, Richard L, Jauberteau MO, Battu S, Lalloué F, Oncotarget 2016, 7, 50349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zeng AL, Yan W, Liu YW, Wang Z, Hu Q, Nie E, Zhou X, Li R, Wang XF, Jiang T, You YP, Oncogene 2017, 36, 5369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Garnier D, Meehan B, Kislinger T, Daniel P, Sinha A, Abdulkarim B, Nakano I, Rak J, Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ricklefs F, Mineo M, Rooj AK, Nakano I, Charest A, Weissleder R, Breakefield XO, Chiocca EA, Godlewski J, Bronisz A, Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Schweiger MW, Li M, Giovanazzi A, Fleming RL, Tabet EI, Nakano I, Würdinger T, Chiocca EA, Tian T, Tannous BA, Adv. Biosyst 2020, 1900312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Gyuris A, Navarrete-Perea J, Jo A, Cristea S, Zhou S, Fraser K, Wei Z, Krichevsky AM, Weissleder R, Lee H, Gygi SP, Charest A, Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, Cell 2011, 144, 646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Friedl P, Alexander S, Cell 2011, 147, 992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Chen F, Zhuang X, Lin L, Yu P, Wang Y, Shi Y, Hu G, Sun Y, BMC Med. 2015, 13, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kore RA, Abraham EC, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2014, 453, 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Guescini M, Genedani S, Stocchi V, Agnati LF, J. Neural Transm 2010, 117, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hallal S, Mallawaaratchy DM, Wei H, Ebrahimkhani S, Stringer BW, Day BW, Boyd AW, Guillemin GJ, Buckland ME, Kaufman KL, Mol. Neurobiol 2019, 56, 4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Oushy S, Hellwinkel JE, Wang M, Nguyen GJ, Gunaydin D, Harland TA, Anchordoquy TJ, Graner MW, Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B 2018, 373, 20160477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Bian EB, Chen EF, Di Xu Y, Yang ZH, Tang F, Ma CC, Wang HL, Zhao B, Int. J. Oncol 2019, 54, 713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Bronisz A, Wang Y, Nowicki MO, Peruzzi P, Ansari KI, Ogawa D, Balaj L, De Rienzo G, Mineo M, Nakano I, Ostrowski MC, Hochberg F, Weissleder R, Lawler SE, Chiocca EA, Godlewski J, Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Gao X, Zhang Z, Mashimo T, Shen B, Nyagilo J, Wang H, Wang Y, Liu Z, Mulgaonkar A, Hu XL, Piccirillo SGM, Eskiocak U, Davé DP, Qin S, Yang Y, Sun X, Fu YX, Zong H, Sun W, Bachoo RM, ping Ge W, Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z, Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX, Nat. Immunol 2013, 14, 1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Hamilton A, Sibson NR, Mol. Cell. Neurosci 2013, 53, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Abusamra AJ, Zhong Z, Zheng X, Li M, Ichim TE, Chin JL, Min WP, Blood Cells, Mol. Dis 2005, 35, 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lundholm M, Schröder M, Nagaeva O, Baranov V, Widmark A, Mincheva-Nilsson L, Wikström P, PLoS One 2014, 9, 108925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Muller L, Mitsuhashi M, Simms P, Gooding WE, Whiteside TL, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 32643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Clayton A, Mitchell JP, Court J, Linnane S, Mason MD, Tabi Z, J. Immunol 2008, 180, 7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Clayton A, Mitchell JP, Court J, Mason MD, Tabi Z, Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 7458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Clayton A, Al-Taei S, Webber J, Mason MD, Tabi Z, J. Immunol 2011, 187, 676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].De Vrij J, Niek Maas SL, Kwappenberg KMC, Schnoor R, Kleijn A, Dekker L, Luider TM, De Witte LD, Litjens M, Van Strien ME, Hol EM, Kroonen J, Robe PA, Lamfers ML, Schilham MW, Broekman MLD, Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Liu ZM, Bin Wang Y, Yuan XH, Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev 2013, 14, 309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].van der Vos KE, Abels ER, Zhang X, Lai C, Carrizosa E, Oakley D, Prabhakar S, Mardini O, Crommentuijn MHW, Skog J, Krichevsky AM, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Mempel TR, El Khoury J, Hickman SE, Breakefield XO, Neuro Oncol. 2016, 18, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Ricklefs FL, Alayo Q, Krenzlin H, Mahmoud AB, Speranza MC, Nakashima H, Hayes JL, Lee K, Balaj L, Passaro C, Rooj AK, Krasemann S, Carter BS, Chen CC, Steed T, Treiber J, Rodig S, Yang K, Nakano I, Lee H, Weissleder R, Breakefield XO, Godlewski J, Westphal M, Lamszus K, Freeman GJ, Bronisz A, Lawler SE, Chiocca EA, Sci. Adv 2018, 4, eaar2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Hellwinkel JE, Redzic JS, Harland TA, Gunaydin D, Anchordoquy TJ, Graner MW, Neuro Oncol. 2016, 18, 497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Domenis R, Cesselli D, Toffoletto B, Bourkoula E, Caponnetto F, Manini I, Beltrami AP, Ius T, Skrap M, Di Loreto C, Gri G, PLoS One 2017, 12, 0169932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Ridder K, Sevko A, Heide J, Dams M, Rupp AK, Macas J, Starmann J, Tjwa M, Plate KH, Schlaudraff H, Altevogt P, Umansky V, Momma S, Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, 1008371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Carmeliet P, Jain RK, Nature 2000, 407, 249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Bre S, Cotran R, Folkman J, J. Natl. Cancer Inst 1972, 48, 347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Reiss Y, Machein MR, Plate KH, Brain Pathol. 2006, 15, 311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Schmidt NO, Westphal M, Hagel C, Ergün S, Stavrou D, Rosen EM, Lamszus K, Int. J. Cancer 1999, 84, 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Das S, Marsden PA, N. Engl. J. Med 2013, 369, 1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Abdel Hadi L, Anelli V, Guarnaccia L, Navone S, Beretta M, Moccia F, Tringali C, Urechie V, Campanella R, Marfia G, Riboni L, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Millimaggi D, Mari M, D’Ascenzo S, Carosa E, Jannini EA, Zucker S, Carta G, Pavan A, Dolo V, Neoplasia 2007, 9, 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Kim CW, Lee HM, Lee TH, Kang C, Kleinman HK, Gho YS, Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 6312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Feng Q, Zhang C, Lum D, Druso JE, Blank B, Wilson KF, Welm A, Antonyak MA, Cerione RA, Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 14450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Maji S, Chaudhary P, Akopova I, Nguyen PM, Hare RJ, Gryczynski I, Vishwanatha JK, Mol. Cancer Res 2017, 15, 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Kerbel RS, Allison AC, Rak J, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Skog J, Würdinger T, van Rijn S, Meijer DH, Gainche L, Curry WT, Carter BS, Krichevsky AM, Breakefield XO, Nat. Cell Biol 2008, 10, 1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Giusti I, Delle Monache S, Di Francesco M, Sanità P, D’Ascenzo S, Gravina GL, Festuccia C, Dolo V, Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Kucharzewska P, Christianson HC, Welch JE, Svensson KJ, Fredlund E, Ringnér M, Mörgelin M, Bourseau-Guilmain E, Bengzon J, Belting M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Treps L, Perret R, Edmond S, Ricard D, Gavard J, Extracell J. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1359479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Svensson KJ, Kucharzewska P, Christianson HC, Sköld S, Löfstedt T, Johansson MC, Mörgelin M, Bengzon J, Ruf W, Belting M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Sun X, Ma X, Wang J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Bihl JC, Chen Y, Jiang C, Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Li CCY, Eaton SA, Young PE, Lee M, Shuttleworth R, Humphreys DT, Grau GE, Combes V, Bebawy M, Gong J, Brammah S, Buckland ME, Suter CM, RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Lang HL, Hu GW, Chen Y, Liu Y, Tu W, Lu YM, Wu L, Xu GH, Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci 2017, 21, 959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Lai A, Tran A, Nghiemphu PL, Pope WB, Solis OE, Selch M, Filka E, Yong WH, Mischel PS, Liau LM, Phuphanich S, Black K, Peak S, Green RM, Spier CE, Kolevska T, Polikoff J, Fehrenbacher L, Elashoff R, Cloughesy T, J. Clin. Oncol 2011, 29, 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, Henriksson R, Saran F, Nishikawa R, Carpentier AF, Hoang-Xuan K, Kavan P, Cernea D, Brandes AA, Hilton M, Abrey L, Cloughesy T, N. Engl. J. Med 2014, 370, 709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Mu W, Rana S, Zöller M, Neoplasia 2013, 15, 875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].LeBlanc R, Catley LP, Hideshima T, Lentzsch S, Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Neuberg D, Goloubeva O, Pien CS, Adams J, Gupta D, Richardson PG, Munshi NC, Anderson KC, Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Morad G, Moses MA, J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1627164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Shao H, Chung J, Lee K, Balaj L, Min C, Carter BS, Hochberg FH, Breakefield XO, Lee H, Weissleder R, Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Shao H, Chung J, Balaj L, Charest A, Bigner DD, Carter BS, Hochberg FH, Breakefield XO, Weissleder R, Lee H, Nat. Med 2012, 18, 1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Berenguer J, Lagerweij T, Zhao XW, Dusoswa S, van der Stoop P, Westerman B, Gooijer MCD, Zoetemelk M, Zomer A, Crommentuijn MHW, Wedekind LE, López-López À, Giovanazzi A, Bruch-Oms M, va. der Meulen-Muileman IH, Reijmers RM, van Kuppevelt TH, García-Vallejo JJ, van Kooyk Y, Tannous BA, Wesseling P, Koppers-Lalic D, Vandertop WP, Noske DP, van Beusechem VW, van Rheenen J, Pegtel DM, van Tellingen O, Wurdinger T, J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1446660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].André-Grégoire G, Bidère N, Gavard J, Biochimie 2018, 155, 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Zhang Z, Yin J, Lu C, Wei Y, Zeng A, You Y, J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res 2019, 38, 6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Yin J, Zeng A, Zhang Z, Shi Z, Yan W, You Y, EBioMedicine 2019, 42, 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Dai X, Liao K, Zhuang Z, Chen B, Zhou Z, Zhou S, Lin G, Zhang F, Lin Y, Miao Y, Li Z, Huang R, Qiu Y, Lin R, Int. J. Oncol 2019, 54, 261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Pavlyukov MS, Yu H, Bastola S, Minata M, Shender VO, Lee Y, Zhang S, Wang J, Komarova S, Wang J, Yamaguchi S, Alsheikh HA, Shi J, Chen D, Mohyeldin A, Kim SH, Shin YJ, Anufrieva K, Evtushenko EG, Antipova NV, Arapidi GP, Govorun V, Pestov NB, Shakhparonov MI, Lee LJ, Nam DH, Nakano I, Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Simon T, Pinioti S, Schellenberger P, Rajeeve V, Wendler F, Cutillas PR, King A, Stebbing J, Giamas G, Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Smyth T, Kullberg M, Malik N, Smith-Jones P, Graner MW, Anchordoquy TJ, J. Controlled Release 2015, 199, 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Ohno SI, Takanashi M, Sudo K, Ueda S, Ishikawa A, Matsuyama N, Fujita K, Mizutani T, Ohgi T, Ochiya T, Gotoh N, Kuroda M, Mol. Ther 2013, 21, 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Aswad H, Forterre A, Wiklander OPB, Vial G, Danty-Berger E, Jalabert A, Lamazière A, Meugnier E, Pesenti S, Ott C, Chikh K, El-Andaloussi S, Vidal H, Lefai E, Rieusset J, Rome S, Diabetologia 2014, 57, 2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Hood JL, San Roman S, Wickline SA, Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Grange C, Tapparo M, Bruno S, Chatterjee D, Quesenberry PJ, Tetta C, Camussi G, Int. J. Mol. Med 2014, 33, 1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Zhou S, Abdouh M, Arena V, Arena M, Arena GO, PLoS One 2017, 12, 0169899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Maas SLN, De Vrij J, Van Der Vlist EJ, Geragousian B, Van Bloois L, Mastrobattista E, Schiffelers RM, Wauben MHM, Broekman MLD, Nolte-’T Hoen ENM, J. Controlled Release 2015, 200, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Pužar Dominkuš P, Stenovec M, Sitar S, Lasič E, Zorec R, Plemenitaš A, Žagar E, Kreft M, Lenassi M, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2018, 1860, 1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Takov K, Yellon DM, Davidson SM, J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1388731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Lai CP, Mardini O, Ericsson M, Prabhakar S, Maguire CA, Chen JW, Tannous BA, Breakefield XO, ACS Nano 2014, 8, 483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Mondal A, Ashiq KA, Phulpagar P, Singh DK, Shiras A, Biol. Proced. Online 2019, 21, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Hwang DW, Choi H, Jang SC, Yoo MY, Park JY, Choi NE, Oh HJ, Ha S, Lee YS, Jeong JM, Gho YS, Lee DS, Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 15636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Varga Z, Gyurkó I, Pálóczi K, Buzás EI, Horváth I, Hegedus N, Máthé D, Szigeti K, Cancer Biother. Radiopharm 2016, 31, 168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Morishita M, Takahashi Y, Nishikawa M, Sano K, Kato K, Yamashita T, Imai T, Saji H, Takakura Y, J. Pharm. Sci 2015, 104, 705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Busato A, Bonafede R, Bontempi P, Scambi I, Schiaffino L, Benati D, Malatesta M, Sbarbati A, Marzola P, Mariotti R, Int. J. Nanomed 2016, 11, 2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Hu L, Wickline SA, Hood JL, Magn. Reson. Med 2015, 74, 266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Gangadaran P, Hong CM, Ahn BC, Biomed Res. Int 2017, 2017, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Tannous BA, Nat. Protoc 2009, 4, 582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Badr CE, Tannous BA, Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Lai CP, Kim EY, Badr CE, Weissleder R, Mempel TR, Tannous BA, Breakefield XO, Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 7029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Zaborowski MP, Cheah PS, Zhang X, Bushko I, Lee K, Sammarco A, Zappulli V, Maas SLN, Allen RM, Rumde P, György B, Aufiero M, Schweiger MW, Lai CPK, Weissleder R, Lee H, Vickers KC, Tannous BA, Breakefield XO, Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 17387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Takahashi Y, Nishikawa M, Shinotsuka H, Matsui Y, Ohara S, Imai T, Takakura Y, J. Biotechnol 2013, 165, 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Suetsugu A, Honma K, Saji S, Moriwaki H, Ochiya T, Hoffman RM, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2013, 65, 383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Chen L, Brigstock DR, Methods Mol. Biol 2017, 1489, 465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Hyenne V, Ghoroghi S, Collot M, Bons J, Follain G, Harlepp S, Mary B, Bauer J, Mercier L, Busnelli I, Lefebvre O, Fekonja N, Garcia-Leon MJ, Machado P, Delalande F, López AA, Silva SG, Verweij FJ, van Niel G, Djouad F, Peinado H, Carapito C, Klymchenko AS, Goetz JG, Dev. Cell 2019, 48, 554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Ridder K, Keller S, Dams M, Rupp AK, Schlaudraff J, Del Turco D, Starmann J, Macas J, Karpova D, Devraj K, Depboylu C, Landfried B, Arnold B, Plate KH, Höglinger G, Sültmann H, Altevogt P, Momma S, PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, 1001874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Krol I, Castro-Giner F, Maurer M, Gkountela S, Szczerba BM, Scherrer R, Coleman N, Carreira S, Bachmann F, Anderson S, Engelhardt M, Lane H, Jeffry Evans TR, Plummer R, Kristeleit R, Lopez J, Aceto N, Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Sullivan JP, Nahed BV, Madden MW, Oliveira SM, Springer S, Bhere D, Chi AS, Wakimoto H, Michael Rothen-berg S, Sequist LV, Kapur R, Shah K, John Iafrate A, Curry WT, Loeffler JS, Batchelor TT, Louis DN, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA, Cancer Discovery 2014, 4, 1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Santiago-Dieppa DR, Steinberg J, Gonda D, Cheung VJ, Carter BS, Chen CC, Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn 2014, 14, 819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Catalano M, O’Driscoll L, J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1703244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].Kosgodage US, Uysal-Onganer P, MacLatchy A, Mould R, Nunn AV, Guy GW, Kraev I, Chatterton NP, Thomas EL, Inal JM, Bell JD, Lange S, Transl. Oncol 2019, 12, 513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [158].Fraser K, Jo A, Giedt J, Vinegoni C, Yang KS, Peruzzi P, Chiocca EA, Breakefield XO, Lee H, Weissleder R, Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [159].Im H, Shao H, Il Park Y, Peterson VM, Castro CM, Weissleder R, Lee H, Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32, 490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]