Local gingival environmental changes occur in the transition from periodontal health to disease. These changes impact both the microbiome at these sites and the juxtaposed gingival tissues. This study focused on the changes related to apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia as biologic markers of these disease changes.

Keywords: apoptosis, autophagy, hypoxia, nonhuman primate, periodontitis

Summary

Oral mucosal tissues must react with and respond to microbes comprising the oral microbiome ecology. This study examined the interaction of the microbiome with transcriptomic footprints of apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia pathways during periodontitis. Adult Macaca mulatta (n = 18; 12–23 years of age) exhibiting a healthy periodontium at baseline were used to induce progressing periodontitis through ligature placement around premolar/molar teeth. Gingival tissue samples collected at baseline, 0·5, 1 and 3 months of disease and at 5 months for disease resolution were analysed via microarray. Bacterial samples were collected at identical sites to the host tissues and analysed using MiSeq. Significant changes in apoptosis and hypoxia gene expression occurred with initiation of disease, while autophagy gene changes generally emerged later in disease progression samples. These interlinked pathways contributing to cellular homeostasis showed significant correlations between altered gene expression profiles in apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia with groups of genes correlated in different directions across health and disease samples. Bacterial complexes were identified that correlated significantly with profiles of host genes in health, disease and resolution for each pathway. These relationships were more robust in health and resolution samples, with less bacterial complex diversity during disease. Using these pathways as cellular responses to stress in the local periodontal environment, the data are consistent with the concept of dysbiosis at the functional genomics level. It appears that the same bacteria in a healthy microbiome may be interfacing with host cells differently than in a disease lesion site and contributing to the tissue destructive processes.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- HOMD

Human Oral Microbiome Database

- POMD

Primate Oral Microbiome Database

INTRODUCTION

The oral microbiome continuously challenges a range of cells and tissues in the oral cavity that results in activation of innate immune, inflammatory and even adaptive immune pathways. This response includes an array of cells and biomolecules primarily designed to create a symbiotic relationship with the microbes with a goal of maintaining homeostasis and clinical health. However, chronic periodontitis results from an immunoinflammatory destruction of the epithelial barrier, connective tissue and alveolar bone. The dysregulated host inflammatory and immune responses are directly linked to the evolution of dysbiotic microbial biofilms at sites of periodontal lesions. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Historical data have documented microbial changes in disease with specific members of the ecology at disease sites appearing to signify these alterations (e.g., Porphyromonas gingivalis). 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 It is still not clear which of the species or complexes of bacteria are aetiologic in the initiation and progression of a disease lesion; however, substantial information has documented their ability to elicit biologic responses from various host cells that could account for the tissue breakdown of periodontitis. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 However, the current paradigm of the microbiology of periodontitis focuses on the importance of the overall microbiome, interactions including co‐operation and competition among the members, and synergism in the virulence potential of the altered, that is dysbiotic, disease microbiome. 18 , 19

In the context of the microbiome, the oral tissues are required to react with and respond to the breadth of microbes comprising this ecology. Even in health, the tissues need to continually remodel and renew, which requires a constant acquisition of nutrients. However, the microbiome clearly exerts some stress on the host cell biology that with microenvironmental changes with disease increases substantially. Manifestations of these interactions included cellular turnover via programmed cell death (i.e., apoptosis). Apoptosis contributes to maintaining an intact epithelial barrier and regulating the local immunoinflammatory responses. An additional process crucial for maintaining tissue integrity within the periodontal environment, autophagy, is a cellular process for engulfing microbes or damaged cell material for eventual degradation, and recycling intracellular components for nutrition during stress. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Cells with defective autophagy pathways exhibit exaggerated inflammation and increased susceptibility to infections. Additionally, various microbial species appear to modulate autophagy as a virulence strategy to enable persistent survival inside host cells affecting both anti‐microbial and anti‐inflammatory responses. The impact of both apoptosis and autophagy on anti‐microbial and anti‐inflammatory properties suggests that alterations could contribute to the pathogenesis of periodontitis, enabling persistent infection and survival in the oral epithelium via enhanced evasion of host responses. Also related to these types of host stress responses is hypoxia (i.e., oxygen deprivation) that can occur in human tissues and cells, particularly during diseases including chronic inflammation. As the disease‐related subgingival sulcus increases, it creates a hypoxic environment supporting the emergence of anaerobic bacteria; this would put stress on host cells. Low oxygen conditions activate the hypoxia signalling pathway, primarily via the hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 (HIF‐1). 24 , 25 , 26 , 27

The human microbiome differs qualitatively and quantitatively in health, gingivitis and periodontitis, 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 particularly related to anaerobic, asaccharolytic species of bacteria that increase in the enriched nutritional environments of inflamed sites 32 and reflecting low oxygen levels. 33 , 34 In this vein, existing data have identified that selected oral bacteria, often considered as periodontopathogens, produce components that inhibit apoptotic pathways, 35 , 36 , 37 can modulate autophagic responses 35 , 38 , 39 and can impact hypoxic responses in host cells. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43

Examination of gene expression profiles in gingival tissues of nonhuman primates, Macaca mulatta, demonstrated altered patterns of apoptotic, 44 , 45 autophagic 46 , 47 and hypoxic 48 genes that were affected by ageing and naturally occurring periodontitis. This study focused on the analysis of the expression of targeted gene sets related to the pathways of apoptosis, various phases of autophagy and hypoxic stress using a nonhuman primate model of progressing periodontitis. The gingival transcriptome expression was specifically integrated with the characteristics of the oral microbiome to model health and progressing disease to identify patterns that would distinguish the risk of the tissues to express destructive processes during periodontitis.

METHODS

Nonhuman primate model and Oral clinical evaluation

Macaca mulatta (n = 18; eight females and 10 males) housed at the Caribbean Primate Research Center (CPRC) were used in these studies. 45 The adult animals were 12–23 years of age. The nonhuman primates are fed a supplemented diet of 20% protein, 5% fat and 10% fibre monkey diet (diet 8773, Teklad NIB primate diet modified: Harlan Teklad). A protocol conforming to ARRIVE guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Puerto Rico enabled clinical measures of periodontal health/disease including probing pocket depth (PPD) and bleeding on probing (BOP) using full‐mouth measures with four sites/tooth. 49 A ligature‐induced periodontitis model was implemented as we have described previously, by tying 3‐0 silk sutures around the necks of maxillary and mandibular premolar and 1st and 2nd molar teeth in three quadrants in each animal. 50 The untreated quadrant was used to obtain baseline healthy tissue and microbiome samples from each animal (Table 1)

TABLE 1.

Clinical features of periodontitis in ligature‐induced disease

| Monkey | BOP | PPD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | 0·5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | BL | 0·5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Male | 1·2 ± 0·8 | 3·8 ± 0·7* | 3·7 ± 0·8* | 1·9 ± 1·6* | 2·2 ± 1·2* | 2·9 ± 0·4 | 5·3 ± 1·1* | 5·3 ± 1·1* | 5·0 ± 1·2* | 3·6 ± 0·4* |

| Female | 1·5 ± 0·7 | 3·6 ± 0·8* | 4·3 ± 0·5* | 2·0 ± 0·8* | 1·8 ± 0·8 | 2·7 ± 0·5 | 4·9 ± 1·2* | 4·9 ± 1·1* | 3·8 ± 1·2* | 3·0 ± 0·4 |

Values denote means ± 1 SD. BOP units are based upon a scale from 1 to 5, and PPD units are in mm.

Abbreviations: BOP, bleeding on probing; PPD, probing pocket depth.

Statistically significant difference from baseline values.

Tissue sampling and gene expression microarray analysis

As reported previously, we used a standard gingivectomy technique (a crevicular incision followed by an interdental incision at the base of the papillae using a #15 surgical blade), and a buccal gingival papillae from either healthy or periodontitis‐affected tissue from the premolar/molar maxillary region of each animal at each time‐point were analysed. The tissues were maintained frozen in RNAlater for microarray analysis (GeneChip® Rhesus Gene 1.0 ST Array [Affymetrix]). 45 Normalization of values across the chips was accomplished through using Affymetrix RMA and the MAS 5 algorithms. 51 For each gene, differences in expression were assessed across the groups using ANOVA (version 9.3; SAS Inc.). The values for the tissues were then compared between the age groups or compared with health versus periodontitis tissues using a t‐test (P < 0·05). The data have been uploaded into the ArrayExpress database (www.ebi.ac.uk) under accession number: E‐MTAB‐1977. Correlations of microbiome and gingival tissue gene expression levels were determined using a Pearson correlation coefficient analysis (P < 0·05). The data have been uploaded to http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/info/submission.html. Previous data from a cross‐sectional study of naturally occurring periodontitis in nonhuman primates focused on a larger array of genes within the apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia pathways. 44 , 47 , 48 Thus, the specific transcripts that showed alterations in the naturally occurring disease were included in this analysis and focused on a set of apoptosis genes (n = 27; pro‐ and anti‐apoptosis), autophagy genes (n = 33) and hypoxia pathway genes (n = 35; Supplmental Table S1).

Analysis of oral microbiome

Bacterial samples were obtained by a curette and analysed using a MiSeq instrument 52 , 53 for the total composition of the microbiome from each sample. 54 , 55 , 56 Sequences were clustered into phylotypes based on their sequence similarity, and these binned phylotypes were assigned to their respective taxonomic classification using the Human Oral Microbiome Database (HOMD V13; http://www.homd.org/index.php?name=seqDownload&file&type=R).

Recent reports 57 , 58 have provided a robust description of the substantial similarity in the OTUs described in the HOMD and the sequence reads developed from the microbiome of M. mulatta. The results showed a broad range of species diversity, and number of species per animal with over 140 species detected in these studies. A number of these species are unique to the macaque. The most commonly detected species included Gemella morbillorum (a ‘monkey’ version), Abiotrophia defectiva and species of Lachnospiraceae. Many additional species of Streptococcus, Lachnospiraceae and Selenomomas, novel to the macaque, were also detected. Most importantly, from these and subsequent microbiome studies, our collaborators (B.J. Paster, The Forsyth Institute, personal communication) are constructing a Primate Oral Microbiome Database (POMD) consisting of about 125 macaque‐specific phylotypes. 59 , 60 , 61

Raw data were deposited at the NIH NCBI (BioProject ID PRJNA516659). Statistical differences in bacterial OTUs were determined with a t‐test (P < 0·05). Correlations of OTUs within the oral microbiome were determined using a Pearson correlation coefficient analysis (P < 0·05). Correlations between the microbiome components and the gingival gene expression were determined only for matching samples derived from the same tooth in each of the animals. Matching samples with sufficient microbiome signals were compared for 11 healthy, 37 diseased and 11 resolution samples that demonstrated 43 991–234 369 reads.

RESULTS

Altered gene expression in periodontitis

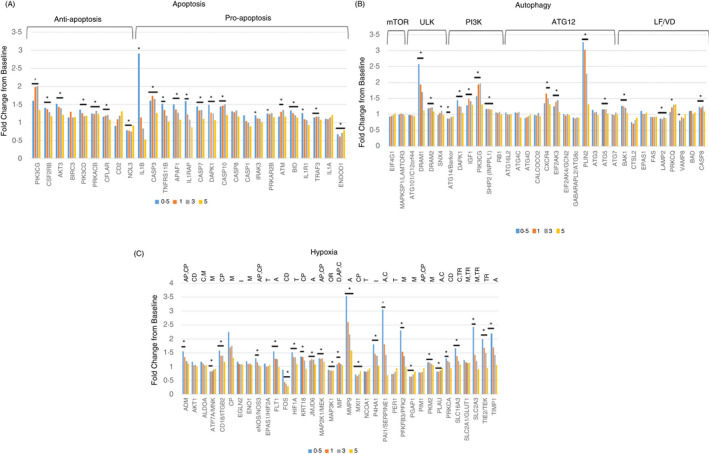

The results in Figure 1 summarize the characteristics of altered gene expression profiles in gingival tissues following ligature‐induced periodontitis, as well as clinical disease resolution. Of the 27 genes examined, a subset of both pro‐ and anti‐apoptotic genes were altered with disease (Figure 1A). The majority of these increased expression levels occurred with disease initiation (0·5 months) and continued to be significantly elevated throughout progression. Generally, the expression decreased to baseline levels in the disease‐resolved tissues. Only NOL3 and ENDOD1 were significantly decreased from health during disease.

FIGURE 1.

Gene expression patterns for apoptosis (A), autophagy (B) and hypoxia (C) genes in gingival tissues (18 samples/time‐point; expect month 1 with 17 samples) during disease (0·5, 1, 3 months) and in resolution (5 months) tissues compared as a fold change from baseline. The asterisk denotes differences from baseline at P < 0·01. See Supplemental Table S1 for denotation of functional relationship of the genes in each of the pathways

Genes associated with multiple complexes/steps in the autophagy pathway were also affected with disease initiation and progression (Figure 1B). These were particularly notable in the early events (ULK, PI3K), as well as in the more terminal events of autophagy (ATG12, LF/VD). Interestingly, in contrast to apoptosis genes that tended to be upregulated to a greater extent at disease initiation, the autophagy gene increases were more prominent during disease progression.

Figure 1C describes the effects of periodontitis on expression of hypoxia genes. Similar to the apoptosis gene expression, the majority of genes that were significantly elevated were greatest at disease initiation and stayed elevated throughout disease progression. Also of interest were a number of genes that were down‐regulated (ATP7A/MNK, FOS, MAP3K1, MXI1, PGAP1, PLAU) that represented varied aspects of hypoxia effects on cell and tissue functions.

Gene expression relationships in periodontitis

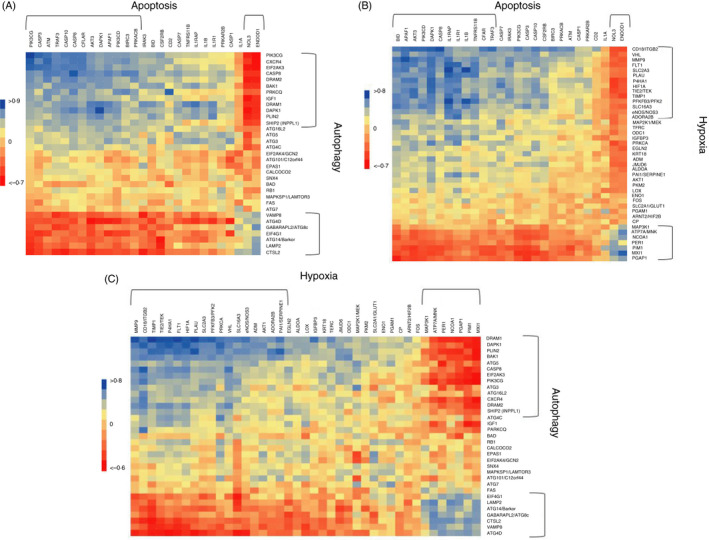

As apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia have some shared pathway genes and clearly functionally interact in cellular stress responses, we evaluated relationships in gene expression patterns across these cellular functions and responses within the gingival tissues. Figure 2A summarizes correlations among the apoptosis and autophagy gene pathways. The results show clear correlations with a subset of apoptosis genes that are significantly positively or negatively correlated with the panel of autophagy genes. Only NOL3 (nucleolar protein 3) and ENDOD1 (endonuclease domain‐containing 1) had a predilection for negative correlations with autophagy genes that contrasted with the primary pattern of these pathway correlations. Figure 2B provides a similar comparison of apoptosis and hypoxia genes. Again, there was clear evidence of significant positive and negative correlations of genes in these two pathways. Both NOL3 and ENDOD1 demonstrated an inverse pattern of correlations with the hypoxia genes. It was noted that only approximately 50% of the apoptosis genes that correlated with both autophagy and hypoxia were similar and that these relationships trended towards representation by pro‐apoptotic genes. Figure 2C describes correlations between autophagy and hypoxia gene expression. A distinct subset of the hypoxia genes was significantly positively correlated with a group of the autophagy genes, generally representing genes in later steps of autophagy. A separate unique set of hypoxia genes was significantly negatively correlated with this same panel of autophagy genes, as well as being positively associated with genes contributing to late stages of autophagosome formation and functions. Comparison across these cellular functional pathways demonstrated many similarities and conserved genes that represented interacting biological activities in the gingival tissues during disease.

FIGURE 2.

Heat maps of correlations of gene expression (89/samples from all time‐points) between apoptosis and autophagy (A), apoptosis and hypoxia (B), and autophagy and hypoxia (C). The brackets enclose groups of genes with similar patterns of correlations. Significant correlation at > 0·324 or <−0·324 with P < 0·001

Bacterial complexes in apoptosis gene expression

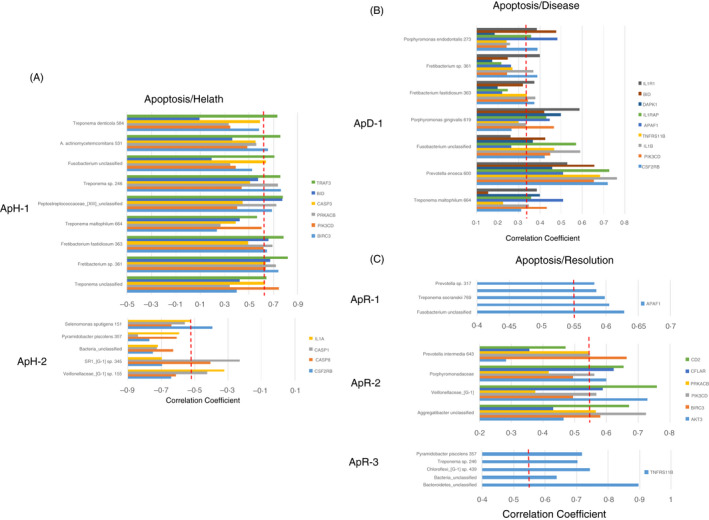

The nonhuman primate model of progressing periodontitis also enables a sample strategy and data outcomes that can ‘match’ microbiome features and changes with gingival transcriptomic patterns in health, disease and resolution of periodontitis. Figure 3A–C provides a summation of the identified bacterial complexes that significantly correlate with groups of apoptosis genes in health, disease and resolution. Two complexes were discovered in health, both of which primarily associated with pro‐apoptotic genes. This included a complex (ApH‐1) with representatives often considered within the pathogenic mix in periodontitis that positively correlated with these genes and a complex (ApH‐2) that significantly negatively correlated with various pro‐apoptotic genes. Only one dominant complex was identified in disease (ApD‐1) that was primarily comprised of microorganisms considered as pathogens, and principally correlated positively with pro‐apoptotic gene expression. Finally, three complexes were related to gene expression in resolution samples. Two of these complexes (ApR‐1 and ApR‐3) were only significantly positively correlated with an individual apoptotic gene. However, the major complex (ApR‐2) was positively correlated with anti‐apoptosis gene expression.

FIGURE 3.

Identification of bacterial complexes with significant correlations to apoptosis genes in health (A; n = 11), disease (combined initiation, progression; B; n = 37) and resolution (C; n = 11)‐derived gingival samples. The red dashed line denotes the level of significance P < 0·05. Designations for bacterial complexes represent apoptosis/health (ApH), apoptosis/disease (ApD) or apoptosis/resolution (ApR)

Bacterial complexes in autophagy gene expression

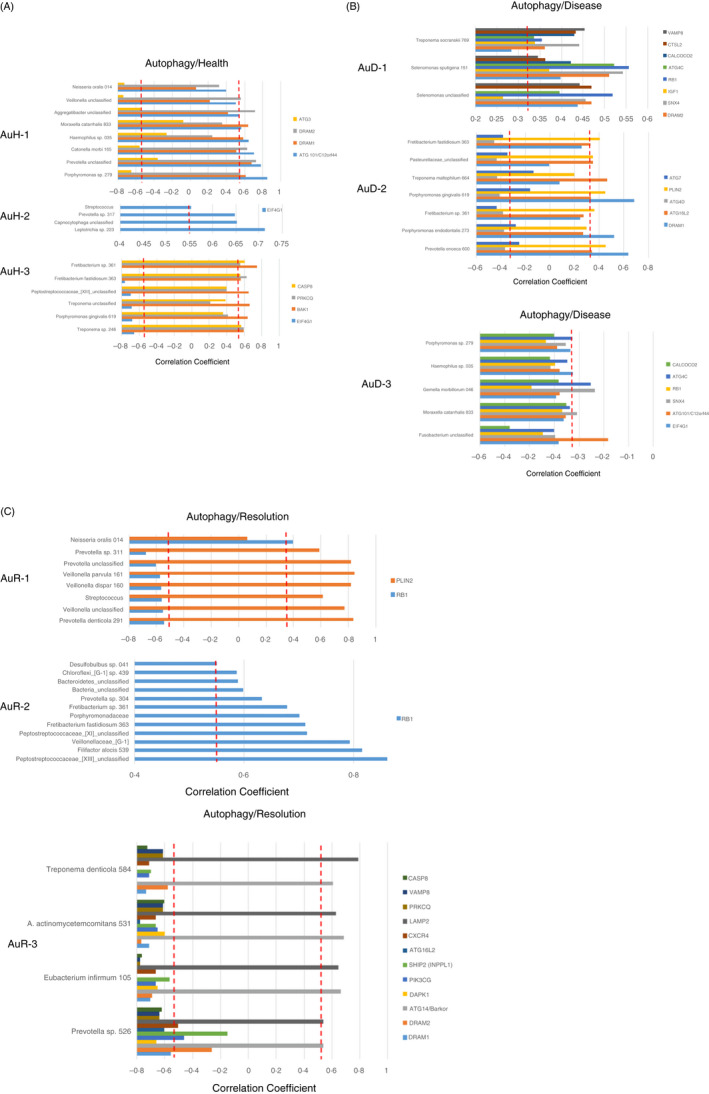

Three complexes were identified that correlated with autophagy genes in healthy samples (Figure 4A). AuH‐1 was comprised of numerous commensal bacteria and was correlated positively with early autophagy events. AuH‐2 was another group of commensals that only correlated with levels of EIF4G1 (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma 1) associated with mTORC1 complex, an early event in autophagy. In contrast, AuH‐3 was comprised primarily of bacteria considered pathogens and significantly positively correlated with LF/VD genes, and was negatively correlated with an early mTORC1 regulatory gene. Transitioning to disease, AuD‐2 comprised a similar bacterial complex as AuH‐3, and demonstrated correlations with genes in the ATG12 autophagy complex particularly negatively correlated with ATG7 as critical component for autophagy and cytoplasmic to vacuole transport, as well as modulating p53‐dependent cell cycle pathways during prolonged metabolic stress (Figure 4B). Additionally, this complex positively correlated with DRAM2 (DNA damage‐regulated autophagy modulator 2), a downregulator of early autophagy events. AuD‐1 was composed of a limited set of commensal bacteria and was positively correlated with genes representing early to late events in autophagy. This finding was coupled with the AuD‐3 complex that was generally composed of commensals that significantly negatively correlated with early events in autophagy. Microbial complex association with autophagy genes in resolution samples showed two large complexes (AuR‐1 and AuR‐2) that correlated with a rather limited number of genes with RB1 negatively (AuR‐1) and positively (AuR‐2) related with the different complexes (Figure 4C). However, AuR‐3 was the dominant complex and generally negatively correlated with a large number of autophagy genes with about ½ early genes and ½ late genes in the pathway.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of bacterial complexes with significant correlations to autophagy genes in health (A; n = 11), disease (combined initiation, progression; B; n = 37) and resolution (C; n = 11)‐derived gingival samples. The red dashed line denotes the level of significance P < 0·05. Designations for bacterial complexes represent autophagy/health (AuH), autophagy/disease (AuD) or autophagy/resolution (AuR)

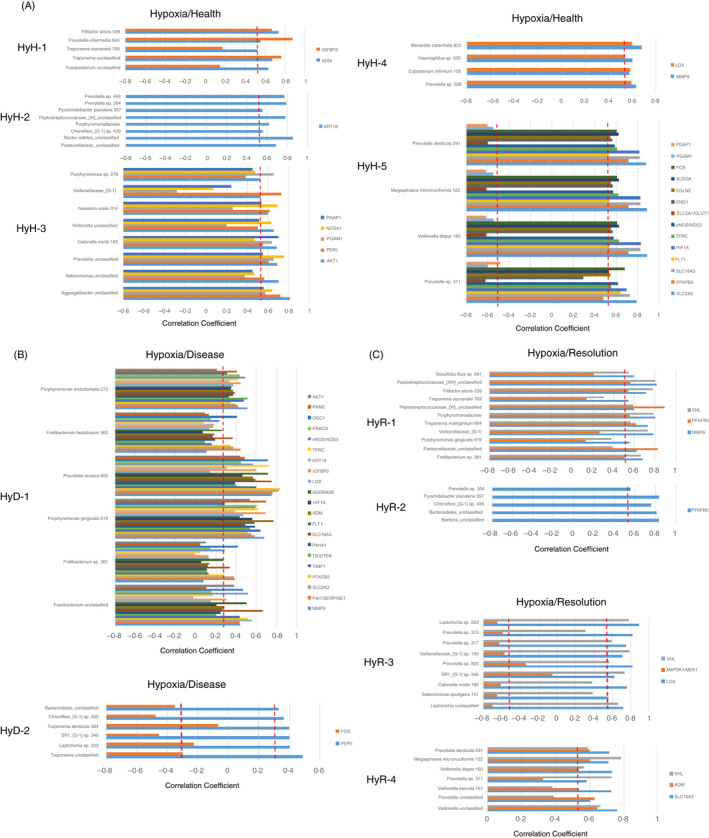

Bacterial complexes in hypoxia gene expression

Figure 5 provides a similar analysis for bacterial complexes related to the expression of hypoxia genes in the gingival tissues. Five complexes were found in healthy samples (Figure 5A) with HyH‐1, HyH‐2 and HyH‐4 positively correlated with a limited set of genes with no distinctive functional pattern. In contrast, HyH‐3 and HyH‐5 showed relationships to the expression of an array of genes. HyH‐3 positively correlated with the expression of both transcription factors and metabolic genes related to hypoxia. However, the HyH‐5 bacterial complex appeared very active in individual complex member bacteria's relationship to hypoxia pathway genes. Generally, there was a significant positive correlation with this complex and the hypoxia gene expression encompassing multiple functions within the pathway. However, a number of metabolic genes (PGAP1, PGAM1, SLC2A1/GLUT1) were negatively correlated with this bacterial complex in health. A substantial consolidation of microbial–host interactions was noted with hypoxia genes during the disease process (Figure 5B). Only two complexes were identified (HyD‐1 and HyD‐2) with HyD‐1 demonstrating a large number of correlations, all of which were positive related to 21 hypoxia genes spanning the breadth of biologic functions within this pathway. As importantly, this complex was primarily composed of bacterial species considered as periodontal pathogens. HyD‐2, composed of a mix of oral commensals and potential pathogens, demonstrated a positive correlation with PER1 as transcription factor and a negative correlation with FOS that would be involved in cellular differentiation. Finally, four clusters of bacteria were identified (HyR‐1, HyR‐2, HyR‐3 and HyR‐4; Figure 5C) in samples from disease‐resolved sites. While each of these complexes was composed of numerous individual species, all tended to be a mixture of commensals and proposed pathogens. Moreover, each of them positively correlated with a rather limited number of hypoxia genes, with only HyR‐3 showing a negative correlation with MAP2K1/MEK1 related to hypoxia functions.

FIGURE 5.

Identification of bacterial complexes with significant correlations to hypoxia genes in health (A; n = 11), disease (combined initiation, progression; B; n = 37) and resolution (C; n = 11)‐derived gingival samples. The red dashed line denotes the level of significance P < 0·05. Designations for bacterial complexes represent hypoxia/health (HyH), hypoxia/disease (HyD) or hypoxia/resolution (HyR)

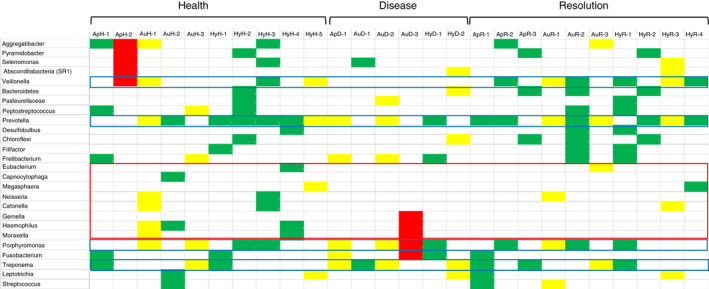

Finally, Figure 6 summarizes the distribution of bacterial phylotypes that appeared in the complexes and correlated with gene expression across the apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia pathways in health, disease and resolved tissue samples. First of note was that many more of the bacterial phylotypes significantly correlated with healthy (n = 28) and resolved (n = 21) versus diseased (n = 14) apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia pathway genes. Second, while many of the phylotypes in the microbial complexes demonstrated overall positive correlations that were identified across the multiple host pathways, there appeared some predilection for these relationships to autophagy and hypoxia genes. Third, the phylotypes within individual disease microbial complexes demonstrated patterns of both positive and negative correlations (i.e., yellow boxes) to groups of genes representing each of the host pathways. Fourth, there appeared to be patterns of phylotypes (Veillonella, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Treponema) in bacterial complexes that showed 10 or greater significant correlations with genes across all these pathways in health, disease and resolution. Thus, these may represent bacterial phylotypes that could be more involved in stress‐associated responses of the oral mucosa. Finally, a group of the phylotypes was not represented in microbial complexes that correlated with genes in these pathways both during disease and with resolution (Eubacterium, Capnocytophaga, Megasphaera, Neisseria, Catonella, Geella, Haemophilus, Moraxella), and appears consistent with alterations in the abundance of these phylotypes independent of the stress pathway gene profiles.

FIGURE 6.

Identification of individual phylotypes comprising the various bacterial complexes in health, disease and resolution samples with significant correlations to apoptosis (Ap), autophagy (Au) or hypoxia (Hy) genes. Green denotes significant positive correlation to all pathway genes, yellow denotes the mixture of positive and negative significant correlations to various pathway genes, and red denotes significant negative correlation to all pathway genes. The blue boxes highlight phylotypes represented in 10 or more of the bacterial complexes that significantly correlated with the expression of genes across the three pathways. The red box identifies a group of phylotypes with minimal host gene expression correlations in samples from clinical disease and resolved tissues

DISCUSSION

Numerous intracellular processes are required to keep cells healthy and enable them to effectively respond to extrinsic signalling, particularly microenvironmental stressors on the cell. These intracellular responses include pathways of programmed cell death (apoptosis), cellular component recycling related to nutrient deprivation (autophagy) and oxygen tension needed for aerobic cellular metabolism (hypoxia). As periodontitis represents a chronic stress on the gingival tissue cells, driven by bacteria and their components triggering dysregulated inflammatory responses, the presence of a transcriptomic footprint related to these pathways in gingival tissues was explored. A nonhuman primate model of ligature‐induced periodontitis 50 was used to compare the footprints in healthy tissues, during disease initiation and progression, and following removal of the ligature resulting in a clinically resolved lesion. The model also enabled an examination of the relationship between members of the oral microbiome at sites juxtaposed to the host response profiles in lesions.

The results demonstrated distinctive patterns for elevated or decreased gene expression signals in apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia. With both apoptosis and hypoxia, the largest gene expression changes generally occurred at disease initiation (0·5 months), while in autophagy these changes appeared to maximize during disease progression (1 and/or 3 months). Finally, few of the genes in any of these pathways were altered in the resolution samples compared with baseline healthy tissues. Also noted were significant correlations in gene expression profiles of individual genes between these different pathways, including both significantly positive and significantly negative correlations suggesting the potential for important synergistic features and cross‐regulation between apoptosis and autophagy in cellular stress reactions. 62 , 63 , 64 Existing literature supports that autophagy provides some level of protection for the cell and contributes to cellular biology processes leading to a decision point of survival or death. In this regard, some of the identified genes in this study could provide additional targets to mechanistically understand molecular mechanisms of cell death in mucosal tissues, such as the gingiva. For example, NOL3 and ENDOD1 could be targets of this crosstalk between pathways.

From these findings were we able to ask questions regarding the potential more specific relationship between different bacteria or bacterial complexes and individual or groups of host genes reflecting a responsiveness that may be specifically dictated by these bacteria. The data demonstrated complexes of bacteria correlating with gene profiles in health, disease and resolution for each of the pathways. The patterns of these bacterial–host correlations were notably similar in healthy and resolution samples. While a number of the bacteria overlapped in complexes in health and disease, most often the correlation direction with host genes differed and the specific genes that were correlated were different in health and disease.

The availability of new technologies and implementation of multi‐parameter ‘omics’ to incorporate a systems biology approach to defining disease has expanded the type of questions, as well as providing very large datasets to query to address these gaps in knowledge. Periodontitis is a chronic immunoinflammatory lesion that reflects a persistent inflammatory response to the oral microbiome. It is clear that the overall bacterial burden increases in disease biofilms and includes the emergence of selected genera/species of bacteria that hallmark these biofilms and likely have some synergistic aetiology for initiation and progression of the lesion. However, the field remains rather unaware of the potential direct interactions and control of the host response armamentarium that occurs in situ by the individual or complexes of bacteria in regulating critical pathways. Numerous cell biology studies have been reported examining individual oral bacteria, albeit primarily proposed pathogens, and single cell‐type cultures. These studies have often focused on single genes and/or products associated with innate immunity and inflammation. 65 , 66 The results clearly demonstrate variation in outcomes based upon the specific challenge and the host cell culture being examined. The field has also progressed somewhat with studies of more complex microbe or biofilm challenge of individual cell types, 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 and inclusion of a broader array of responses using multiplex assays, microarrays or RNA‐Seq assessment of the cellular transcriptome. 1 , 71 , 72 , 73 Finally, a more limited group of investigations has explored the use of organotypic cell cultures and responses to microbial challenge. 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 Nevertheless, each of these has some limitations regarding recapitulating the complexity of the in situ host response, as well as the oral microbiome with the potential for a few hundred species and substantial variation between individuals.

Human studies have been conducted to examine differences in the gingival transcriptome in health and disease coupled in some cases with a limited exploration of the bacterial ecology. 72 , 73 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 These studies have provided insights into genes and pathways demonstrating substantial differences and provided more specific data examining differential expression of critical transcription factors and the potential for miRNA to regulate gene expression and disease outcomes. However, one limitation of these cross‐sectional studies is the lack of clinical markers to identify the phase of the individual periodontal lesions, 82 , 83 , 84 which would be expected to contribute to the heterogeneity of the transcriptome and loss of some power in the final analysis and interpretation. In contrast to these investigations, numerous reports have document changes in the oral microbiome in periodontitis versus health, 19 , 85 , 86 , 87 affected by various modifying factors, 3 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 and comparing starting and ending microbiomes in stable versus progressing sites. 93 The studies generally have not provided any insights into the local host responses to these microbial changes. The nonhuman primate model has been used successfully for decades to examine in additional detail both the microbial aspects, 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 host responses 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 and clinical features of a developing periodontal lesion. Thus, we were able to use this model to identify novel features of the microbiome and gingival transcriptome at specific time‐points throughout the disease process.

While it is clear that a wide array of gene expression changes occur within the local tissue environment of the periodontal lesion, this study focused specifically on three stress pathways, apoptosis, autophagy and hypoxia. Numerous mechanisms are involved in maintaining host cell–microbe interactions at mucosal surfaces to enhance a homeostatic relationship. Apoptosis represents a controlled mechanism of epithelial cell viability and death to maintain physiological and renewal of capabilities for epithelial surfaces. More recent results have also emphasized that this pathway represents an intrinsic innate immune mechanism to help control microbial infections. 103 Apoptotic cell death is considered an essential mechanism that regulates the anti‐pathogen immunoinflammatory response via anti‐inflammatory signals and activating regulatory immune cells. 104 , 105 The role of autophagy in infection and inflammation is also a relatively recent concept that has a clear role in chronic inflammatory diseases 38 , 106 , 107 via regulated cellular responses to environmental stressors that would occur with infection and inflammation. Finally, within the periodontal milieu, the disease environment selects for the emergence of more anaerobic, asaccharolytic bacterial species that strongly correlate with disease expression and progression. These outcomes would suggest a hypoxic local microenvironment with lesion formation. Hypoxia signalling dysregulation commonly occurs during chronic inflammation, with both sustained hypoxia and intermittent hypoxia enhancing the NF‐κB inflammatory pathway. 108 These results demonstrated numerous interactions in gene expression across the three pathways. Also observed was that upregulation of both apoptosis and hypoxia appeared earlier with disease initiation, while autophagy changes were reflected in later phases of disease progression. In health, the bacterial complexes related to apoptosis and hypoxia exhibited substantial overlap, while in resolved site microbiomes, parallels were noted for the bacterial complexes across all three pathways. Even though these complexes demonstrated similarities in health and disease, the complexes in disease were less robust and showed differential correlations with the host pathway genes than those observed in health and resolution. Thus, at least for these pathways, the data are consistent with the concept of dysbiosis at the functional genomics level, where the same bacteria in a healthy microbiome may be interfacing with host cells differently in a disease lesion site and contributing to the tissue destructive processes. Further studies will need to better clarify whether these variations in correlations in this study are reflecting overall tissue differences or whether the differences in health and disease reflect changing microbial interactions with different cell types during lesion progression.

Nevertheless, certain considerations need to be described related to the limitations of this model system. First, the ligatures in primates do elicit both soft and hard tissue changes related to periodontal lesions, albeit, generally the animals do not lose substantial bone architecture in this experimental model that does occur in naturally occurring disease. Second, while the ligature clearly increases the accumulation of bacteria and does provide some mechanical disruption to the tissues that differs somewhat from human disease, the oral microbiome in the nonhuman primates shows extensive overlap in changes observed with naturally occurring 57 and ligature‐induced disease. 56 , 109 Additionally, we have shown that gingival gene expression profiles documenting local host response features for a number of pathways are comparable in naturally occurring and ligature‐induced disease models. 47 , 110 Finally, epidemiologic data support various demographic modifiers (e.g., age, sex) of periodontitis expression in humans, as well as the identification of substantial individual variation in risk for more extensive and severe disease. While the ligature model does not necessarily reflect this individual feature of human periodontitis, we have shown that the magnitude of ligature‐induced disease in the nonhuman primates is altered by age 56 and sex, 111 as well as recent data demonstrating matriline (e.g., genetic, familial) susceptibility age of onset and extent of disease. 112 , 113 Thus, the evidence suggests that this model should be able to provide some insights into the earliest phases of disease initiation and progression that would be difficult to obtain in a human disease model.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict with any information provided in the report.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JE and OG contributed to conception, design, data acquisition and interpretation of the data, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript, and SK contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supporting information

Table S1 Listing of host genes examined for apoptosis and autophagy processes in the gingival tissues. Fxn identified general function for the gene. Functions are denoted as: anti‐apoptosis (A), pro‐apoptosis (P); mTORC1 complex (mTOR), ULK complex (ULK), PI3K complex (PI3K), ATG12 interactions (ATG12), and lysosome fusion/vesicle degradation (LF/VD); angiogenesis (A), regulation of apoptosis (AP), coagulation (C), cell differentiation (CD), regulation of cell proliferation (CP), DNA damage and repair (D), HIF interactors (I), metabolism (M), other response genes (OR), transcription/co‐transcription factors (T), and transporters/channels/receptors (TR).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant P20GM103538. We express our gratitude to the Caribbean Primate Research Center (CPRC) supported by grant P40RR03640 and the Center for Oral Health Research in the College of Dentistry at the University of Kentucky. We thank Drs. M.J. Novak (University of Kentucky) and L. Orraca (University of Puerto Rico) for their support in the clinical aspects of the protocol. We thank Drs. J. Gonzalez Martinez and A.G. Burgos Rodriguez from the Caribbean Primate Research Center for animal husbandry and sampling support. We also thank the Microarray Core and the Genomic Core Laboratory of University Kentucky for their invaluable technical assistance and Dr. A. Stromberg (University of Kentucky) for initial normalization of the host response data.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The microbiome and transcriptome datasets have been deposited as described in the Methods.

REFERENCES

- 1. Solbiati J, Frias‐Lopez J. Metatranscriptome of the oral microbiome in health and disease. J Dent Res. 2018;97:492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belibasakis GN. Microbiological changes of the ageing oral cavity. Arch Oral Biol. 2018;96:230–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sudhakara P, Gupta A, Bhardwaj A, Wilson A. Oral dysbiotic communities and their implications in systemic diseases. Dent J. 2018;6:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mira A, Simon‐Soro A, Curtis MA. Role of microbial communities in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases and caries. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(Suppl 18):S23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanner AC, Kent R Jr, Kanasi E, Lu SC, Paster BJ, Sonis ST, et al. Clinical characteristics and microbiota of progressing slight chronic periodontitis in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:917–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paster BJ, Boches SK, Galvin JL, Ericson RE, Lau CN, Levanos VA, et al. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3770–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teles FR, Teles RP, Uzel NG, Song XQ, Torresyap G, Socransky SS, et al. Early microbial succession in redeveloping dental biofilms in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47:95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colombo AP, Boches SK, Cotton SL, Goodson JM, Kent R, Haffajee AD, et al. Comparisons of subgingival microbial profiles of refractory periodontitis, severe periodontitis, and periodontal health using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1421–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:135–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:134–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pandruvada SN, Ebersole JL, Huja SS. Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis by opsonized Porphyromonas gingivalis . FASEB Bioadv. 2019;1:213–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hou Y, Yu H, Liu X, Li G, Pan J, Zheng C, et al. Gingipain of Porphyromonas gingivalis manipulates M1 macrophage polarization through C5a pathway. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2017;53:593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glowczyk I, Wong A, Potempa B, Babyak O, Lech M, Lamont RJ, et al. Inactive gingipains from P. gingivalis selectively skews T cells toward a Th17 phenotype in an IL‐6 dependent manner. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Silva N, Abusleme L, Bravo D, Dutzan N, Garcia‐Sesnich J, Vernal R, et al. Host response mechanisms in periodontal diseases. J Appl Oral Sci. 2015;23:329–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hajishengallis G, Sahingur SE. Novel inflammatory pathways in periodontitis. Adv Dent Res. 2014;26:23–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graves DT, Li J, Cochran DL. Inflammation and uncoupling as mechanisms of periodontal bone loss. J Dent Res. 2011;90:143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holzhausen M, Spolidorio LC, Ellen RP, Jobin MC, Steinhoff M, Andrade‐Gordon P, et al. Protease‐activated receptor‐2 activation: a major role in the pathogenesis of Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1189–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jakubovics NS, Shi W. A new era for the oral microbiome. J Dent Res. 2020;99:595–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Curtis MA, Diaz PI, Van Dyke TE. The role of the microbiota in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83:14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levine B, Kroemer G. Biological functions of autophagy genes: a disease perspective. Cell 2019; 176:11–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galluzzi L, Baehrecke EH, Ballabio A, Boya P, Bravo‐San Pedro JM, Cecconi F, et al. Molecular definitions of autophagy and related processes. EMBO J. 2017;36:1811–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yin Z, Pascual C, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: machinery and regulation. Microb Cell. 2016;3:588–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schneider JL, Cuervo AM. Autophagy and human disease: emerging themes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;26:16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shay JE, Celeste Simon M. Hypoxia‐inducible factors: crosstalk between inflammation and metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gao L, Chen Q, Zhou X, Fan L. The role of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 in atherosclerosis. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:872–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Semenza GL. Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1: regulator of mitochondrial metabolism and mediator of ischemic preconditioning. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Semenza GL. Hypoxia. Cross talk between oxygen sensing and the cell cycle machinery. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C550–C552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verma D, Garg PK, Dubey AK. Insights into the human oral microbiome. Arch Microbiol. 2018;200:525–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mason MR, Preshaw PM, Nagaraja HN, Dabdoub SM, Rahman A, Kumar PS. The subgingival microbiome of clinically healthy current and never smokers. ISME J. 2015;9:268–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ahn J, Yang L, Paster BJ, Ganly I, Morris L, Pei Z, et al. Oral microbiome profiles: 16S rRNA pyrosequencing and microarray assay comparison. PLoS One 2011;6:e22788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE. Molecular microbial diagnosis. Periodontol 2000. 2009;51:38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Periasamy S, Kolenbrander PE. Mutualistic biofilm communities develop with Porphyromonas gingivalis and initial, early, and late colonizers of enamel. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6804–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Battino M, Bullon P, Wilson M, Newman H. Oxidative injury and inflammatory periodontal diseases: the challenge of anti‐oxidants to free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:458–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Torresyap G, Haffajee AD, Uzel NG, Socransky SS. Relationship between periodontal pocket sulfide levels and subgingival species. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:1003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taxman DJ, Swanson KV, Broglie PM, Wen H, Holley‐Guthrie E, Huang MT, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis mediates inflammasome repression in polymicrobial cultures through a novel mechanism involving reduced endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:32791–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yao L, Jermanus C, Barbetta B, Choi C, Verbeke P, Ojcius DM, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection sequesters pro‐apoptotic Bad through Akt in primary gingival epithelial cells. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2010;25:89–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boisvert H, Duncan MJ. Translocation of Porphyromonas gingivalis gingipain adhesin peptide A44 to host mitochondria prevents apoptosis. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3616–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bullon P, Cordero MD, Quiles JL, Ramirez‐Tortosa Mdel C, Gonzalez‐Alonso A, Alfonsi S, et al. Autophagy in periodontitis patients and gingival fibroblasts: unraveling the link between chronic diseases and inflammation. BMC Med. 2012;10:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tsai CC, Chen HS, Chen SL, Ho YP, Ho KY, Wu YM, et al. Lipid peroxidation: a possible role in the induction and progression of chronic periodontitis. J Periodont Res. 2005;40:378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Golz L, Memmert S, Rath‐Deschner B, Jager A, Appel T, Baumgarten G, et al. Hypoxia and P. gingivalis synergistically induce HIF‐1 and NF‐kappaB activation in PDL cells and periodontal diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:438085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bae WJ, Shin MR, Kang SK, Jun Z, Kim JY, Lee SC, et al. HIF‐2 inhibition suppresses inflammatory responses and osteoclastic differentiation in human periodontal ligament cells. J Cell Biochem 2015;166:1241–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jian C, Li C, Ren Y, He Y, Li Y, Feng X, et al. Hypoxia augments lipopolysaccharide‐induced cytokine expression in periodontal ligament cells. Inflammation 2014;37:1413–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Golz L, Memmert S, Rath‐Deschner B, Jager A, Appel T, Baumgarten G, et al. LPS from P. gingivalis and hypoxia increases oxidative stress in periodontal ligament fibroblasts and contributes to periodontitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014; 2014:986264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gonzalez OA, John Novak M, Kirakodu S, Stromberg AJ, Shen S, Orraca L, et al. Effects of aging on apoptosis gene expression in oral mucosal tissues. Apoptosis 2013;18:249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gonzalez OA, Stromberg AJ, Huggins PM, Gonzalez‐Martinez J, Novak MJ, Ebersole JL. Apoptotic genes are differentially expressed in aged gingival tissue. J Dent Res. 2011;90:880–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ebersole JL, Orraca L, Novak MJ, Kirakodu S, Gonzalez‐Martinez J, Gonzalez OA. Comparative analysis of gene expression patterns for oral epithelium‐related functions with aging. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1197:143–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ebersole JL, Kirakodu SS, Novak MJ, Dawson D, Stromberg A, Orraca L, et al. Gingival tissue autophagy pathway gene expression profiles in periodontitis and aging. J Periodont Res. 2020;55. 10.1111/jre.12789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ebersole JL, Novak MJ, Orraca L, Martinez‐Gonzalez J, Kirakodu S, Chen KC, et al. Hypoxia‐inducible transcription factors, HIF1A and HIF2A, increase in aging mucosal tissues. Immunology 2018;154:452–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ebersole JL, Steffen MJ, Gonzalez‐Martinez J, Novak MJ. Effects of age and oral disease on systemic inflammatory and immune parameters in nonhuman primates. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1067–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ebersole JL, Kirakodu S, Novak MJ, Stromberg AJ, Shen S, Orraca L, et al. Cytokine gene expression profiles during initiation, progression and resolution of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:853–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ferrin J, Kirakodu S, Jensen D, Al‐Attar A, Peyyala R, Novak MJ, et al. Gene expression analysis of neuropeptides in oral mucosa during periodontal disease in non‐human primates. J Periodontol. 2018;89:858–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kirakodu S, Chen J, Gonzalez Martinez J, Gonzalez OA, Ebersole J. Microbiome profiles of ligature‐induced periodontitis in nonhuman primates across the lifespan. Infect Immun. 2019;87(6):e00067‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual‐index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: open‐source, platform‐independent, community‐supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011;27:2194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ebersole J, Kirakodu S, Chen J, Nagarajan R, Gonzalez OA. Oral microbiome and gingival transcriptome profiles of ligature‐induced periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2020;99:746–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Colombo APV, Paster BJ, Grimaldi G, Lourenco TGB, Teva A, Campos‐Neto A, et al. Clinical and microbiological parameters of naturally occurring periodontitis in the non‐human primate Macaca mulatta . J Oral Microbiol. 2017;9:1403843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ocon S, Murphy C, Dang AT, Sankaran‐Walters S, Li CS, Tarara R, et al. Transcription profiling reveals potential mechanisms of dysbiosis in the oral microbiome of rhesus macaques with chronic untreated SIV infection. PLoS One 2013;8:e80863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kirakodu SS, Govindaswami M, Novak MJ, Ebersole JL, Novak KF. Optimizing qPCR for the quantification of periodontal pathogens in a complex plaque biofilm. Open Dent J. 2008;2:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Novak MJ, Novak KF, Hodges JS, Kirakodu S, Govindaswami M, Diangelis A, et al. Periodontal bacterial profiles in pregnant women: response to treatment and associations with birth outcomes in the obstetrics and periodontal therapy (OPT) study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1870–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Peyyala R, Kirakodu SS, Ebersole JL, Novak KF. Novel model for multispecies biofilms that uses rigid gas‐permeable lenses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3413–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nikoletopoulou V, Markaki M, Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:3448–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ryter SW, Mizumura K, Choi AM. The impact of autophagy on cell death modalities. Int J Cell Biol. 2014;2014:502676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nakahira K, Cloonan SM, Mizumura K, Choi AM, Ryter SW. Autophagy: a crucial moderator of redox balance, inflammation, and apoptosis in lung disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:474–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ebersole JL, Dawson D 3rd, Emecen‐Huja P, Nagarajan R, Howard K, Grady ME, et al. The periodontal war: microbes and immunity. Periodontol 2000. 2017;75:52–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Meyle J, Chapple I. Molecular aspects of the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2015;69:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gu Y, Han X. Toll‐like receptor signaling and immune regulatory lymphocytes in periodontal disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ramage G, Lappin DF, Millhouse E, Malcolm J, Jose A, Yang J, et al. The epithelial cell response to health and disease associated oral biofilm models. J Periodontal Res. 2017;52:325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hajishengallis G. The inflammophilic character of the periodontitis‐associated microbiota. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2014;29:248–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Belibasakis GN, Kast JI, Thurnheer T, Akdis CA, Bostanci N. The expression of gingival epithelial junctions in response to subgingival biofilms. Virulence 2015;6:704–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nowicki EM, Shroff R, Singleton JA, Renaud DE, Wallace D, Drury J, et al. Microbiota and metatranscriptome changes accompanying the onset of gingivitis. MBio 2018;9:e00575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sawle AD, Kebschull M, Demmer RT, Papapanou PN. Identification of master regulator genes in human periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2016;95:1010–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kebschull M, Demmer RT, Grun B, Guarnieri P, Pavlidis P, Papapanou PN. Gingival tissue transcriptomes identify distinct periodontitis phenotypes. J Dent Res. 2014;93:459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Shang L, Deng D, Buskermolen JK, Roffel S, Janus MM, Krom BP, et al. Commensal and pathogenic biofilms alter toll‐like receptor signaling in reconstructed human gingiva. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pinnock A, Murdoch C, Moharamzadeh K, Whawell S, Douglas CW. Characterisation and optimisation of organotypic oral mucosal models to study Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion. Microbes Infect. 2014;16:310–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bao K, Papadimitropoulos A, Akgul B, Belibasakis GN, Bostanci N. Establishment of an oral infection model resembling the periodontal pocket in a perfusion bioreactor system. Virulence 2015;6:265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bao K, Belibasakis GN, Selevsek N, Grossmann J, Bostanci N. Proteomic profiling of host‐biofilm interactions in an oral infection model resembling the periodontal pocket. Sci Rep. 2015; 5:15999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kebschull M, Guarnieri P, Demmer RT, Boulesteix AL, Pavlidis P, Papapanou PN. Molecular differences between chronic and aggressive periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2013;92:1081–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Stoecklin‐Wasmer C, Guarnieri P, Celenti R, Demmer RT, Kebschull M, Papapanou PN. MicroRNAs and their target genes in gingival tissues. J Dent Res. 2012;91:934–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kebschull M, Papapanou PN. The use of gene arrays in deciphering the pathobiology of periodontal diseases. Methods Mol Biol. 2010; 666:385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Demmer RT, Behle JH, Wolf DL, Handfield M, Kebschull M, Celenti R, et al. Transcriptomes in healthy and diseased gingival tissues. J Periodontol. 2008;79:2112–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Teles R, Moss K, Preisser JS, Genco R, Giannobile WV, Corby P, et al. Patterns of periodontal disease progression based on linear mixed models of clinical attachment loss. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Goodson JM. Diagnosis of periodontitis by physical measurement: interpretation from episodic disease hypothesis. J Periodontol. 1992;63(Suppl 4S):373–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Goodson JM, Tanner AC, Haffajee AD, Sornberger GC, Socransky SS. Patterns of progression and regression of advanced destructive periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9:472–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Papapanou PN, Park H, Cheng B, Kokaras A, Paster B, Burkett S, et al. Subgingival microbiome and clinical periodontal status in an elderly cohort: The WHICAP ancillary study of oral health. J Periodontol. 2020;91(Suppl 1):S56‐S67. 10.1002/JPER.20-0194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Na HS, Kim SY, Han H, Kim HJ, Lee JY, Lee JH, et al. Identification of potential oral microbial biomarkers for the diagnosis of periodontitis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wade WG. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ganesan SM, Dabdoub SM, Nagaraja HN, Scott ML, Pamulapati S, Berman ML, et al. Adverse effects of electronic cigarettes on the disease‐naive oral microbiome. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ebersole JL, Dawson DA 3rd, Emecen Huja P, Pandruvada S, Basu A, Nguyen L, et al. Age and periodontal health ‐ immunological view. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2018;5:229–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Moon JH, Lee JH, Lee JY. Subgingival microbiome in smokers and non‐smokers in Korean chronic periodontitis patients. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2015;30:227–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bizzarro S, Loos BG, Laine ML, Crielaard W, Zaura E. Subgingival microbiome in smokers and non‐smokers in periodontitis: an exploratory study using traditional targeted techniques and a next‐generation sequencing. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Feres M, Teles F, Teles R, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M. The subgingival periodontal microbiota of the aging mouth. Periodontol 2000. 2016;72:30–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yost S, Duran‐Pinedo AE, Teles R, Krishnan K, Frias‐Lopez J. Functional signatures of oral dysbiosis during periodontitis progression revealed by microbial metatranscriptome analysis. Genome Med. 2015;7:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Moncla BJ, Braham PH, Persson GR, Page RC, Weinberg A. Direct detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis in Macaca fascicularis dental plaque samples using an oligonucleotide probe. J Periodontol. 1994;65:398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Holt SC, Ebersole J, Felton J, Brunsvold M, Kornman KS. Implantation of Bacteroides gingivalis in nonhuman primates initiates progression of periodontitis. Science 1988;239:55–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Velusamy SK, Sampathkumar V, Ramasubbu N, Paster BJ, Fine DH. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans colonization and persistence in a primate model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:22307–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schou S, Holmstrup P, Keiding N, Fiehn NE. Microbiology of ligature‐induced marginal inflammation around osseointegrated implants and ankylosed teeth in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7:190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ebersole JL, Cappelli D, Holt SC, Singer RE, Filloon T. Gingival crevicular fluid inflammatory mediators and bacteriology of gingivitis in nonhuman primates related to susceptibility to periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2000;15:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ebersole JL, Kornman KS. Systemic antibody responses to oral microorganisms in the cynomolgus monkey: development of methodology and longitudinal responses during ligature‐induced disease. Res Immunol. 1991;142:829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Blanchard SB, Cox SE, Ebersole JL. Salivary IgA responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis in the cynomolgus monkey. 1. Total IgA and IgA antibody levels to P. gingivalis . Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1991;6:341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Persson GR. Immune responses and vaccination against periodontal infections. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):39–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Persson GR, Engel LD, Whitney CW, Weinberg A, Moncla BJ, Darveau RP, et al. Macaca fascicularis as a model in which to assess the safety and efficacy of a vaccine for periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1994;9:104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Carvalho‐Filho PC, Trindade SC, Olczak T, Sampaio GP, Oliveira‐Neto MG, Santos HA, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis HmuY stimulates expression of Bcl‐2 and Fas by human CD3+ T cells. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Nakahashi‐Oda C, Udayanga KG, Nakamura Y, Nakazawa Y, Totsuka N, Miki H, et al. Apoptotic epithelial cells control the abundance of Treg cells at barrier surfaces. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:441–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Henson PM, Bratton DL. Antiinflammatory effects of apoptotic cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2773–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Memmert S, Nogueira AVB, Damanaki A, Nokhbehsaim M, Eick S, Divnic‐Resnik T, et al. Damage‐regulated autophagy modulator 1 in oral inflammation and infection. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:2933–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Cario E. Innate immune signalling at intestinal mucosal surfaces: a fine line between host protection and destruction. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Nanduri J, Yuan G, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Transcriptional responses to intermittent hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164:277–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Ebersole JL, Kirakodu SS, Neumann E, Orraca L, Gonzalez Martinez J, Gonzalez OA. Oral Microbiome and Gingival Tissue Apoptosis and Autophagy Transcriptomics. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:585414. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.585414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Ebersole JL, Kirakodu S, Novak MJ, Orraca L, Stormberg AJ, Gonzalez‐Martinez J, et al. Comparative analysis of expression of microbial sensing molecules in mucosal tissues with periodontal disease. Immunobiology 2019;224:196–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ebersole JL, Steffen MJ, Reynolds MA, Branch‐Mays GL, Dawson DR, Novak KF, et al. Differential gender effects of a reduced‐calorie diet on systemic inflammatory and immune parameters in nonhuman primates. J Periodontal Res. 2008;43:500–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Ebersole JL, Orraca L, Kensler TB, Gonzalez‐Martinez J, Maldonado E, Gonzalez OA. Periodontal disease susceptible matrilines in the Cayo Santiago Macaca mulatta macaques. J Periodontal Res. 2019;54:134–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Gonzalez OA, Orraca L, Kensler TB, Gonzalez‐Martinez J, Maldonado E, Ebersole JL. Familial periodontal disease in the cayo santiago rhesus macaques. Am J Primatol. 2016;78:143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Listing of host genes examined for apoptosis and autophagy processes in the gingival tissues. Fxn identified general function for the gene. Functions are denoted as: anti‐apoptosis (A), pro‐apoptosis (P); mTORC1 complex (mTOR), ULK complex (ULK), PI3K complex (PI3K), ATG12 interactions (ATG12), and lysosome fusion/vesicle degradation (LF/VD); angiogenesis (A), regulation of apoptosis (AP), coagulation (C), cell differentiation (CD), regulation of cell proliferation (CP), DNA damage and repair (D), HIF interactors (I), metabolism (M), other response genes (OR), transcription/co‐transcription factors (T), and transporters/channels/receptors (TR).

Data Availability Statement

The microbiome and transcriptome datasets have been deposited as described in the Methods.