Abstract

Laryngotracheal trauma is rare but potentially life-threatening as it implies a high risk of compromising airway patency. A consensus on damage control management for laryngotracheal trauma is presented in this article. Tracheal injuries require a primary repair. In the setting of massive destruction, the airway patency must be assured, local hemostasis and control measures should be performed, and definitive management must be deferred. On the other hand, management of laryngeal trauma should be conservative, primary repair should be chosen only if minimal disruption, otherwise, management should be delayed. Definitive management must be carried out, if possible, in the first 24 hours by a multidisciplinary team conformed by trauma and emergency surgery, head and neck surgery, otorhinolaryngology, and chest surgery. Conservative management is proposed as the damage control strategy in laryngotracheal trauma.

Keywords: larynx, laryngotracheal trauma, penetrating trauma, neck trauma, tracheostomy, cricoid cartilage, thyroid cartilage, laryngeal edema, neck injuries, subcutaneous emphysema

Resumen

El trauma laringotraqueal es poco frecuente, pero con alto riesgo de comprometer la permeabilidad la vía aérea. El presente artículo presenta el consenso de manejo de control de daños del trauma laringotraqueal. En el manejo de las lesiones de tráquea se debe realizar un reparo primario; y en los casos con una destrucción masiva se debe asegurar la vía aérea, realizar hemostasia local, medidas de control y diferir el manejo definitivo. El manejo del trauma laríngeo debe ser conservador y diferir su manejo, a menos que la lesión sea mínima y se puede optar por un reparo primario. El manejo definitivo se debe realizar durante las primeras 24 hora por un equipo multidisciplinario de los servicios de cirugía de trauma y emergencias, cirugía de cabeza y cuello, otorrinolaringología, y cirugía de tórax. Se propone optar por la estrategia de control de daños en el trauma laringotraqueal.

Palabras clave: laringe, trauma laringotraqueal, trauma penetrante, trauma de cuello, traqueotomía, cartílago cricoides, cartílago tiroideo, edema laríngeo, lesiones de cuello, enfisema subcutáneo

Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| Laryngotracheal trauma is rare but potentially life-threatening. A consensus on damage control management for laryngotracheal trauma is presented in this article. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| The priority in laryngotracheal damage control is to secure the airway and identify the severity of the lesion. Definitive management must be carried out in the first 24 hours by a multidisciplinary team. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| The consensus allows to make an opportune decision between a primary repair or a conservative approach, which includes an optimal metabolic resuscitation and posterior definitive management within the first 24 hours. |

Introduction

Laryngotracheal trauma is a rare entity, with an incidence of 1 in 125,000 visits to the emergency department 1 . Laryngotracheal injuries are reported in 0.1 to 10% of those with cervical trauma and involvement of adjacent structures has been evidenced in 66.9% of these cases 1 - 4 . Since this type of trauma can produce airway obstruction, maintaining its permeability becomes a priority. In the context of unstable hemodynamic patients with components of lethal diamond (acidosis, hypothermia, coagulopathy, and hypocalcemia), laryngotracheal trauma may require temporary maneuvers through damage control surgery 3 - 5 . This article aims to present laryngeal and tracheal trauma management following basic damage control surgery principles.

This consensus synthesizes the experience earned during the past 30 years in trauma critical care management of the severely injured patient from the Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group (CTE) of Cali, Colombia, which is made up of experts from the University Hospital Fundación Valle del Lili, the University Hospital del Valle "Evaristo García", the Universidad del Valle and Universidad Icesi, the Asociación Colombiana de Cirugía, the Pan-American Trauma Society and the collaboration of national and international specialists of the United States of America.

Epidemiology

Laryngotracheal trauma incidence is variable; the US National Emergency Service Sample reports an incidence of 1 in 125,000 visits to the emergency department 1 . Shaefer reported an incidence of 1 in 30,000 emergency department visits and 1 out of each 445 patients admitted with head-neck injuries 6 , 7 . Airway injuries present a mortality rate of 82% at the scene 8 .

Traffic accidents are the leading cause of laryngeal trauma, accounting for 26% to 37% of the cases 1 , 7 followed by direct trauma to the neck and sports injuries in 32% of the patients 9 . While in areas with a higher incidence of penetrating trauma, gunshot wounds are the main cause 1 , 7 . The severity of laryngeal injuries is assessed according to Schaefer-Fuhrman’s classification (Table 1). Grade I injuries are the most frequent, present in 52% of the patients 10 , followed by Grade II injuries representing 37% to 45% of the cases 6 , 7 . Laryngeal trauma mortality rate is reported between 1.6% and 11% and is associated with secondary lesions 1 , 6 , 7 , 10 .

Table 1. Schaeffer-Furhrmans classification of laryngeal injuries.

| Grade of laryngeal injury | Description of the injury |

|---|---|

| I | Minor endolaryngeal hematoma, without detectable fracture |

| II | Edema, hematoma, minor mucosal disruption without exposed cartilage, and nondisplaced fractures |

| III | Massive endolaryngeal edema, extensive mucosal lacerations, exposed cartilage, displaced fracture or vocal cord immobility |

| IV | Same as grade III, but with anterior larynx disruption, unstable fractures, > 2 fracture lines or severe mucosal injury |

| V | Complete laryngotracheal disruption |

Tracheal injuries are usually located at the second or sixth tracheal ring and have been described as tears or partial to complete ruptures 8 . The clinical approach differs depending on the traumatic mechanism, which varies according to the geographical area. The management of patients with blunt trauma can be conservative in up to 65% of patients 1 , while in penetrating trauma, the management is mainly operative 11 - 13 . Mortality can be around 25% in blunt tracheal trauma, and 13.6% in penetrating trauma 11 , 14 .

Initial approach and diagnosis

The clinical features of laryngotracheal trauma are variable and have been reported from asymptomatic presentations to patients presenting with dyspnea, stridor and hoarseness; the latter is known as the laryngeal trauma triad 15 , 16 . Other symptoms such as dysphonia, neck pain, and hemoptysis have been described. Physical examination edema, crushing of the thyroid cartilage bulge, abnormal palpation of the laryngeal outline, crepitation, subcutaneous emphysema, blowing wound, or decreased respiratory rate can be observed 1 , 17 , 18 .

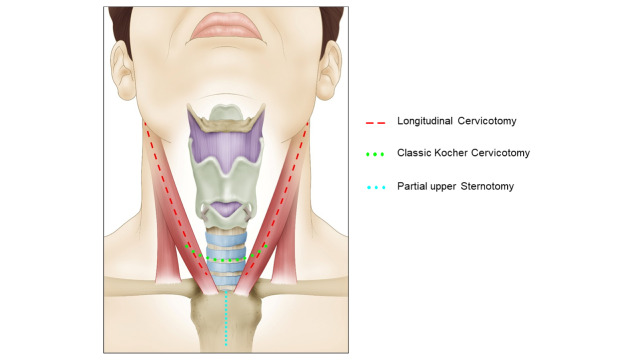

Nonetheless, these symptoms and signs do not necessarily indicate an initial emergency surgical approach. In contrast, imminent risk of airway obstruction, active bleeding, expansive hematoma, evolving cerebral ischemia, and refractory hemodynamic instability suggest an injury with a high risk of mortality or the possibility of generating medium and long term sequelae. In this scenario, a surgical approach through cervicotomy is indicated (Figure 1). In the case of hemodynamic stability, the patient should be evaluated by a CT scan with intravenous contrast 19 - 21 .

Figure 1. Surgical Approach to the Larynx or Tracheal Injuries. Three incisions can be used for the surgical approach to the laryngotracheal area: 1. Longitudinal Cervicotomy (over the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (red line)), 2. Transverse Cervicotomy (the Kocher type incision, 3 cm above the sternal manubrium (green line)), and if necessary, a 3. Partial sternotomy (blue line).

Management

In the surgical management of laryngeal and tracheal trauma, the priorities are evaluating the risk of airway obstruction and classifying the severity of the injury. Laryngeal injuries are grouped into five grades according to the Shaefer-Furhman’s classification (Table 1). There is no severity classification for tracheal injuries, but the presence of partial or complete disruption, with or without massive destruction of the trachea can be used as a reference.

The steps for the management of this type of trauma are:

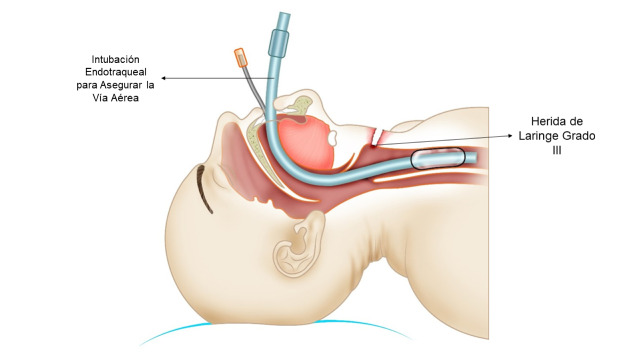

Step 1. Secure the airway: All patients with hemodynamic instability or high risk of a difficult airway, should undergo orotracheal intubation by expert personnel, through direct vision, ideally using a fiberoptic bronchoscope, placing the balloon distal to the lesion and without applying pressure on the cricoid cartilage. If orotracheal intubation is not possible, the need for an emergency tracheostomy or a cricothyroidotomy, as a last resource, should be evaluated. If the patient is not at risk of airway compromise, secondary screening studies can be performed. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Airway Management. Orotracheal intubation is the preferred strategy to secure the airway. It must be performed through direct vision, placing the balloon distal to the lesion and without applying pressure on the cricoid cartilage.

Step 2. Identify the degree of the injury: In patients with hemodynamic instability and/or hard signs of vascular/airway lesions, direct exploration of the laryngotracheal area is indicated by performing either a transverse cervicotomy through the Kocher incision 3 cm above the sternal manubrium, or a longitudinal cervicotomy following the medial edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle from the jugular or sternal notch to the mastoid. These maneuvers allow a proper exploration of the posterior laryngotracheal wall, esophagus, and blood vessels. In some cases, it will be necessary to extend the sternal incision with a partial sternotomy to achieve a better exposition of the distal segment of the cervical trachea and the cervicothoracic junction in the exploration of associated vascular lesions at the thoracic outlet level (Figure 1).

Laryngeal Trauma:

In massive laryngeal edema, with local bleeding and without disruption of the airway, a conservative approach and local hemostasis maneuvers should be performed.

For grade II laryngeal lesions, a simple suture using 3-0 absorbable monofilament should be performed.

Finally, for grade III-IV-V laryngeal lesions, primary repair should not be attempted. The airway must be secured by orotracheal intubation, if not possible, a tracheostomy should be made, and management by the head and neck surgery service should be deferred (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Severe Laryngeal Trauma. Grade IV Shaefer-Furhman Laryngeal Injury. Multiple fractures with massive mucosal injury can be observed.

Tracheal Trauma

In tracheal injuries with less than 50% disruption on the circumference, a primary repair should be performed through suture using simple stitches of absorbable monofilament material or 3-0 vicryl.

In tracheal lesions with a disruption greater than 50% of its circumference, the airway must be guaranteed. A primary repair can be attempted by suturing with simple stitches using absorbable monofilament material or 3-0 vicryl. In massive destruction, the airway must be secured, local hemostasis performed, a negative pressure system placed, and the management by head and neck surgery should be delayed (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Surgical Management of Tracheal Injuries. For tracheal injuries with partial disruption of the tracheal ring, a primary repair should be performed with absorbable monofilament 3-0 using interrupted sutures.

In addition to managing the laryngeal or tracheal injury, damage control of associated lesions, hemostasis and packaging should be performed if necessary.

Step 3. Transfer to ICU: after initial control measures, the patient should undergo optimal resuscitation, metabolic stabilization and must achieve recovery from coagulopathy, acidosis, and hypothermia in the ICU. Subsequently, the patient should be evaluated using imaging studies to rule out vascular lesion of the carotid or subclavian artery through a computed tomography angiogram and the risk of an esophageal lesion through esophagoscopy.

If there is strong clinical suspicion and the laryngotracheal lesion has not been identified, an assessment should be made through fibronasolaryngoscopy or fiberoptic bronchoscopy for diagnostic purposes reference for surgical decision making for the head and neck surgery or otolaryngology group.

Step 4: In the first 24 hours, a multidisciplinary team conformed by the emergency and trauma surgeon, the head and neck surgery team, otorhinolaryngology, and thoracic surgery must be notified to decide the best laryngeal or tracheal reconstruction approach.

Discussion

The main challenge when dealing with neck trauma with suspected laryngeal and/or tracheal injury is to ensure airway patency since this is the leading cause of death in this type of trauma 22 . It is considered a difficult airway, and the first management option should be orotracheal intubation under direct vision by expert personnel and without applying pressure on the cricoid. The reported complications associated with this procedure are pharyngeal mucosal or skeletal injury, iatrogenic injury, or respiratory arrest 23 , 24 . Other ways to secure the airway include tracheostomy and endotracheal tube passage through the traumatic wound reported in up to 25% of the cases 6 , 18 , 25 .

The management of this type of trauma depends on the severity of larynx or tracheal injuries. In tracheal injuries, a primary repair should be attempted whenever possible. If the patient appears with massive destruction, airway patency should be guaranteed, along with control measures and management deferral 23 . Tracheostomy is not suggested as the first approach because it may lead to additional damage. It is recommended to define and perform definitive management for laryngotracheal injuries in the early 24 hours since this has shown to provide better airway permeability and voice preservation 7 , 10 . Concerning airway permeability, in 1983, Leopold reported a success rate of 87% when the repair was made within the first 24 hours and 69% when the repair was made between the second and seventh day; on the other hand, voice preservation was achieved in 58% of patients with early repair and only 15% of patients repaired after 48 hours 26 . Posteriorly, Bent et al. reported a significant difference between early and late repair outcomes, where the incidence of complications was lower among patients with early repair (1.6%) compared to those repaired after the first 48 hours (21.4%) 27 . Similarly, Shaefer documented that 86% of the patients who underwent voice repair within the early 24 hours had better outcomes in vocal cord functionality 7 .

Complications

Suture related complications include granuloma formation and anastomosis dehiscence or leakage. The dehiscence in surgical excisions and laryngotracheal or tracheal end-to-end anastomosis occurs in 4.1% to 5.8% of the patients 28 , 29 . Complications are related to the severity of the injury, the anatomical location of the wound, time-lapse until repair, and the presence of secondary lesions.

The complications in laryngotracheal trauma are more frequently manifested in the quality of voice, with sequelae such as hoarseness or permanent dysphonia. The airway obstruction can also generate intolerance to physical activity, limiting the functional capacity. A higher complication rate has been observed in the most severe lesions such as grade IV and V in the Shaefer-Furhman’s classification, which has been estimated at 31% for voice sequelae and 6.1% for any grade of airway obstruction 7 . The glottis compromise is a crucial factor in determining voice impairment and the remaining sequelae 6 .

Conclusion

The priority in laryngotracheal damage control is to secure the airway and identify the degree of the lesion. This allows an opportune decision between a primary repair or a conservative approach, which includes an optimal metabolic resuscitation and definitive posterior management within the first 24 hours. Our recommendation is to opt for conservative management as a damage control measure in laryngotracheal trauma.

References

- 1.Sethi RKV, Khatib D, Kligerman M, Kozin ED, Gray ST, Naunheim MR. Laryngeal fracture presentation and management in United States emergency rooms. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:2341–2346. doi: 10.1002/lary.27790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford HR, Gardner MJ, Lynch JM. Laryngotracheal disruption from blunt pediatric neck injuries Impact of early recognition and intervention on outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:331–335. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90584-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demetriades D, Velmahos GG, Asensio JA. Cervical pharyngoesophageal and laryngotracheal injuries. World J Surg. 2001;25:1044–1048. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angood PB, Attia EL, Brown RA, Mulder DS. Extrinsic civilian trauma to the larynx and cervical trachea-important predictors of long-term morbidity. J Trauma. 1986;26:869–873. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198610000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ditzel RM, Anderson JL, Eisenhart WJ, Rankin CJ, DeFeo DR, Oak S. A review of transfusion- And trauma-induced hypocalcemia Is it time to change the lethal triad to the lethal diamond? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88:434–439. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randall DR, Rudmik L, Ball CG, Bosch JD. Airway management changes associated with rising radiologic incidence of external laryngotracheal injury. Can J Surg. 2018;61:121–127. doi: 10.1503/cjs.012216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaefer SD. The acute management of external laryngeal trauma a 27-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 1992;118:598–604. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880060046013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertelsen S, Howitz P. Injuries of the trachea and bronchi. Thorax. 1972;27:188–194. doi: 10.1136/thx.27.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DePorre AR, Schechtman SA, Hogikyan ND, Thompson A, Westman AJ, Sargent RA. Airway management and clinical outcomes in external laryngeal trauma a case series. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:e52–e54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verschueren DS, Bell RB, Bagheri SC, Dierks EJ, Potter BE. Management of laryngo-tracheal injuries associated with craniomaxillofacial trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider T, Volz K, Dienemann H, Hoffmann H. Incidence and treatment modalities of tracheobronchial injuries in Germany. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;8:571–576. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.196790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim CW, Hwang JJ, Cho HM, Cho JS, I HS, Kim YD. The Surgical outcome for patients with tracheobronchial injury in blunt group and penetrating group. J Trauma Inj. 2016;29:1–7. doi: 10.20408/jti.2016.29.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly JP, Webb WR, Moulder P V, Everson C, Burch BH, Lindsey ES. Management of airway trauma I tracheobronchial injuries. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;40:551–555. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)60347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiser AC. O'Brien SM.Detterbeck FC Blunt tracheobronchial injuries Treatment and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:2059–2065. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02453-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan JYW, Khoo WX, Hing ECH, Yap YL, Lee H, Nallathamby V. An algorithm for the management of concomitant maxillofacial, laryngeal, and cervical spine trauma. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;77:S36–S38. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krausz AA, Krausz MM, Picetti E. Maxillofacial and neck trauma: A damage control approach. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:31–31. doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madkhali EEA, Albati SA, Ahmad HF. Emergency airway management in neck trauma. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;70:409–413. doi: 10.12816/0043478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demetriades D, Theodorou D, Cornwall E, Berne T V, Asensio J, Beizberg H. Evaluation of penetrating injuries of the neck Prospective study of 223 patients. World J Surg. 1997;21:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s002689900191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prichayudh S, Choadrachata-Anun J, Sriussadaporn S, Pak-Art R, Sriussadaporn S, Kritayakirana K. Selective management of penetrating neck injuries using "no zone" approach. Injury. 2015;46:1720–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibraheem K, Khan M, Rhee P, Azim A. O'Keeffe T.Tang A.et al "No zone" approach in penetrating neck trauma reduces unnecessary computed tomography angiography and negative explorations J Surg. Res. 2018;221:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madsen AS, Laing GL, Bruce JL, Oosthuizen G V, Clarke DL. An audit of penetrating neck injuries in a South African trauma service. Injury. 2016;47:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong DC, Breeze J. Damage control surgery and combat-related maxillofacial and cervical injuries A systematic review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mercer SJ, Jones CP, Bridge M, Clitheroe E, Morton B, Groom P. Systematic review of the anaesthetic management of non-iatrogenic acute adult airway trauma. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:i49–i59. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karmy-Jones R, Wood DE. Traumatic injury to the trachea and bronchus. Thorac Surg Clin. 2007;17:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennan J, Gibbons MD, Lopez M, Hayes D, Faulkner J, Eller RL. Traumatic airway management in operation Iraqi freedom. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:376–380. doi: 10.1177/0194599810392666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leopold DA. Laryngeal trauma a historical comparison of treatment methods. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:106–111. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800160040010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bent JP, Silver JR, Porubsky ES. Acute laryngeal trauma A review of 77 patients. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 1993;109:441–449. doi: 10.1177/019459989310900309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright CD, Grillo HC, Wain JC, Wong DR, Donahue DM, Gaissert HA. Anastomotic complications after tracheal resection Prognostic factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:731–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapidzic A, Alagic-Smailbegovic J, Sutalo K, Sarac E, Resic M. Postintubation tracheal stenosis. Med Arch. 2004;58:384–385. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(95)70279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]