Abstract

Hemorrhagic shock and its complications are a major cause of death among trauma patients. The management of hemorrhagic shock using a damage control resuscitation strategy has been shown to decrease mortality and improve patient outcomes. One of the components of damage control resuscitation is hemostatic resuscitation, which involves the replacement of lost blood volume with components such as packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and platelets in a 1:1:1:1 ratio. However, this is a strategy that is not applicable in many parts of Latin America and other low-and-middle-income countries throughout the world, where there is a lack of well-equipped blood banks and an insufficient availability of blood products. To overcome these barriers, we propose the use of cold fresh whole blood for hemostatic resuscitation in exsanguinating patients. Over 6 years of experience in Ecuador has shown that resuscitation with cold fresh whole blood has similar outcomes and a similar safety profile compared to resuscitation with hemocomponents. Whole blood confers many advantages over component therapy including, but not limited to the transfusion of blood with a physiologic ratio of components, ease of transport and transfusion, less volume of anticoagulants and additives transfused to the patient, and exposure to fewer donors. Whole blood is a tool with reemerging potential that can be implemented in civilian trauma centers with optimal results and less technical demand.

Keywords: Crystalloid solutions; shock; hemorrhagic; disseminated intravascular coagulation; trauma centers, blood safety; hemostatics; hypothermia; hypocalcemia; blood coagulation factors; respiratory distress syndrome; compartment syndromes

Resumen

El choque hemorrágico y sus complicaciones son la principal causa de muerte en los pacientes con trauma. La resucitación en control de daños ha demostrado una disminución en la mortalidad y mejoría en el manejo del paciente. La resucitación hemostática consiste en la recuperación del volumen con hemoderivados como glóbulos rojos, plasma, crioprecipitado y plaquetas, en proporciones de 1:1:1:1. Sin embargo, esta demanda de hemo componentes podría no aplicarse para toda Latinoamérica u otros países de medianos y bajos ingresos. Las principales barreras para la implementación de esta estrategia serían la escasa disponibilidad de bancos de sangre y de hemoderivados insuficientes para contar con un protocolo de transfusión masiva. Una propuesta para superar estas barreras es el uso de sangre total fresca fría para la resucitación hemostática de los pacientes exsanguinados. Ecuador ha sido pionero en la implementación de esta estrategia con una experiencia ya de seis años, en que han demostrado que la sangre total tiene ventajas sobre la terapia de hemo componentes incluyendo, pero no limitando, la trasfusión de sangre con una razón fisiológica de componentes, fácil transporte y transfusión, menor volumen de anticoagulantes y aditivos trasfundidos al paciente, y menor exposición a donantes. La sangre total es una herramienta con un potencial reemergente que puede ser implementado en centros de trauma civil con óptimos resultados y menor demanda técnica.

Palabras clave: Sangre total, resucitación de control de daños, transfusión soluciones cristaloides, choque hemorrágico, coagulación intravascular diseminada, centros de trauma, seguridad sanguínea, hemostáticos, hipotermia, hipocalcemia, factores de coagulación sanguínea, síndrome de dificultad respiratoria, síndromes compartimentales

Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| This study aims to discuss the emerging role that whole blood is playing in hemostatic resuscitation for severely injured trauma patients in hemorrhagic shock. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| In damage control resuscitation, the gold standard for resuscitation is a balanced component therapy with a 1:1:1 ratio. This strategy attempts to imitate the composition of the fluid that has been lost, shining light on the new proposals for the use of whole blood in hemostatic resuscitation. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| Whole blood confers numerous practical advantages over component therapy. |

Introduction

The majority of preventable trauma deaths occur due to hemorrhage, with most of these deaths occurring within the first 2-3 hours after injury 1 - 3 . It is estimated that up to one-fourth of trauma-related deaths can be averted with early damage control measures 1 . Intertwined with the concept of damage control surgery is that of damage control resuscitation (DCR), which aims to control hemorrhage, restore tissue hypoxia, and mitigate trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) 1 , 4 , 5 .

Hemostatic resuscitation is a central tenet of DCR 4 and the focus of this review. A blood-based strategy is now considered the standard of care in DCR 2 , 5 - 8 . The current gold-standard is a balanced, 1:1:1 transfusion strategy with packed red blood cells (pRBCs), fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets, as described in several trials throughout the last decade 2 , 9 , 10 . The Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group (CTE) of Cali, Colombia has proposed that the ideal resuscitation should be done in a 1:1:1:1 proportion with pRBCs, FFP, platelets, and cryoprecipitate. Several studies are now challenging this paradigm, suggesting that whole blood rather than balanced component therapy may be the ideal resuscitative fluid 4 , 6 , 11 , 12 . We aim to discuss the emerging role that whole blood is playing in hemostatic resuscitation for severely injured trauma patients in hemorrhagic shock.

This article is a consensus that synthesizes the experience earned during the past 30 years in trauma critical care management of the severely injured patient from the Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group (CTE) of Cali, Colombia which is made up of experts from the University Hospital Fundación Valle del Lili, the University Hospital del Valle "Evaristo García", the Universidad del Valle and Universidad Icesi, the Asociación Colombiana de Cirugia, the Pan-American Trauma Society and the collaboration of national and international specialists of the United States of America and Latin America.

Epidemiology

The availability of blood products has an inverse effect on mortality from hemorrhagic shock caused by trauma. It has recently been described that the presence of at least 4 blood banks per city in Colombia is associated with decreased mortality from hemorrhagic shock in trauma 13 . In a modeling study of the global availability of blood products based on the 2016 World Health Organization - Global Status Report on Blood Safety and Availability, it was estimated that 61% of the 195 included countries did not have sufficient blood products to meet the population’s needs 14 .

The availability of blood products varies among countries; blood donation rates can provide a marker for blood accessibility. Of the 117.4 million blood donations collected worldwide annually, 42% are collected in high-income countries, which are home to only 16% of the world’s population. Blood donation rates per 1000 people are 32.6 in high-income countries, 15.1 in upper-middle-income countries, 8.1 in lower-middle income countries, and 4.4 in low-income countries 15 .

The rate of blood donations in Latin America and the Caribbean was 14.84 per 1,000 population in 2014 16 . The blood donation rate in Colombia in 2015 was 16.07 per 1,000 people. Of the 795,792 donations in one year, 725,209 (91.13%) were registered as voluntary donations and 70,429 (8.85%) were registered as replacement donations 17 .

Pathophysiology

Coagulopathy is present in up to 25% of trauma patients on admission 10 . Macleod et al. 18 , found that an initial prothrombin time (PT) greater that 14 seconds and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) greater than 34 seconds were independent predictors of mortality with adjusted odds ratios of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.11-1.68; p <0.001) and 4.26 (95% CI: 3.23-5.63; p <0.001), respectively. The presence of coagulopathy on admission is associated with increased transfusion requirements, length-of-stay, ventilator support, and multisystem organ failure 19 .

TIC occurs due to a combination of acute trauma coagulopathy and resuscitation-associated coagulopathy 19 . Acute trauma coagulopathy can develop within 30 minutes of injury 20 and occurs due to systemic activation of the coagulation cascade followed by consumption coagulopathy and increased fibrinolysis. Resuscitation-induced coagulopathy contributes to worsening acidosis, hypothermia, and dilution of clotting factors often through excessive crystalloid infusion 19 . Termed the “lethal trial,” coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis can lead to the “vicious cycle of trauma,” which will ultimately lead to death. Hypothermia can lead to decreased platelet and enzyme function. Inadequate tissue perfusion leads to a lactic acidosis that can be further exacerbated with high chloride crystalloid solutions. The activity of coagulation factors also decreases with decreasing blood pH 20 . A recent review by Ditzel et al. 21 , suggests that the concept of the “lethal triad” should be revised to the “lethal diamond,” recognizing the role of hypocalcemia as an independent predictor of mortality and exacerbate coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis 22 .

Prior to the advent of damage control resuscitation, trauma care patient was driven by large boluses of crystalloid solution, which early studies suggested would improve cardiac output and oxygen delivery 23 . A subsequent study by Kasotakis et al. 24 , demonstrated that crystalloid resuscitation was associated with the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome, multisystem organ failure, bloodstream and surgical site infections, as well as abdominal and extremity compartment syndromes in a dose-dependent fashion. Brickell and Mattox’s landmark paper showed an increase in survival with a delay in crystalloid administration to trauma patients 25 . A recent multivariate logistic regression analysis performed on a sample of 3,137 patients receiving crystalloid resuscitation found that fluid volumes of 1.5 L or more was associated with increased mortality in both elderly and nonelderly populations 26 .

The aim of damage control resuscitation is to mitigate the effects of acute trauma coagulopathy, reversal of acidosis, and the prevention of hypothermia 21 . The recognition of the deleterious effects of a crystalloid-based strategy, the pendulum began to swing back toward a balanced and blood-based strategy 11 . Within the past two decades, studies have suggested that the inclusion of FFP and platelets in resuscitation at higher ratios lead to increased survival in bleeding patients with traumatic injuries 9 , 27 . The PROPPR trial, a pivotal study in the trauma literature, found that patients randomized to receive platelets, FFP, and pRBCs in a 1:1:1 ratio had significantly increased hemostasis and decreased death from hemorrhage compared with a group treated with the same products in a 1:1:2 ratio 2 . However, many institutions in low-middle income countries do not have access to blood banks with enough blood products to administer a blood-based resuscitation in a 1:1:1 ratio. The relative success of the 1: 1: 1 formulation and the challenge of its availability have recently rekindled the discussion about the substance being imitated: whole blood itself.

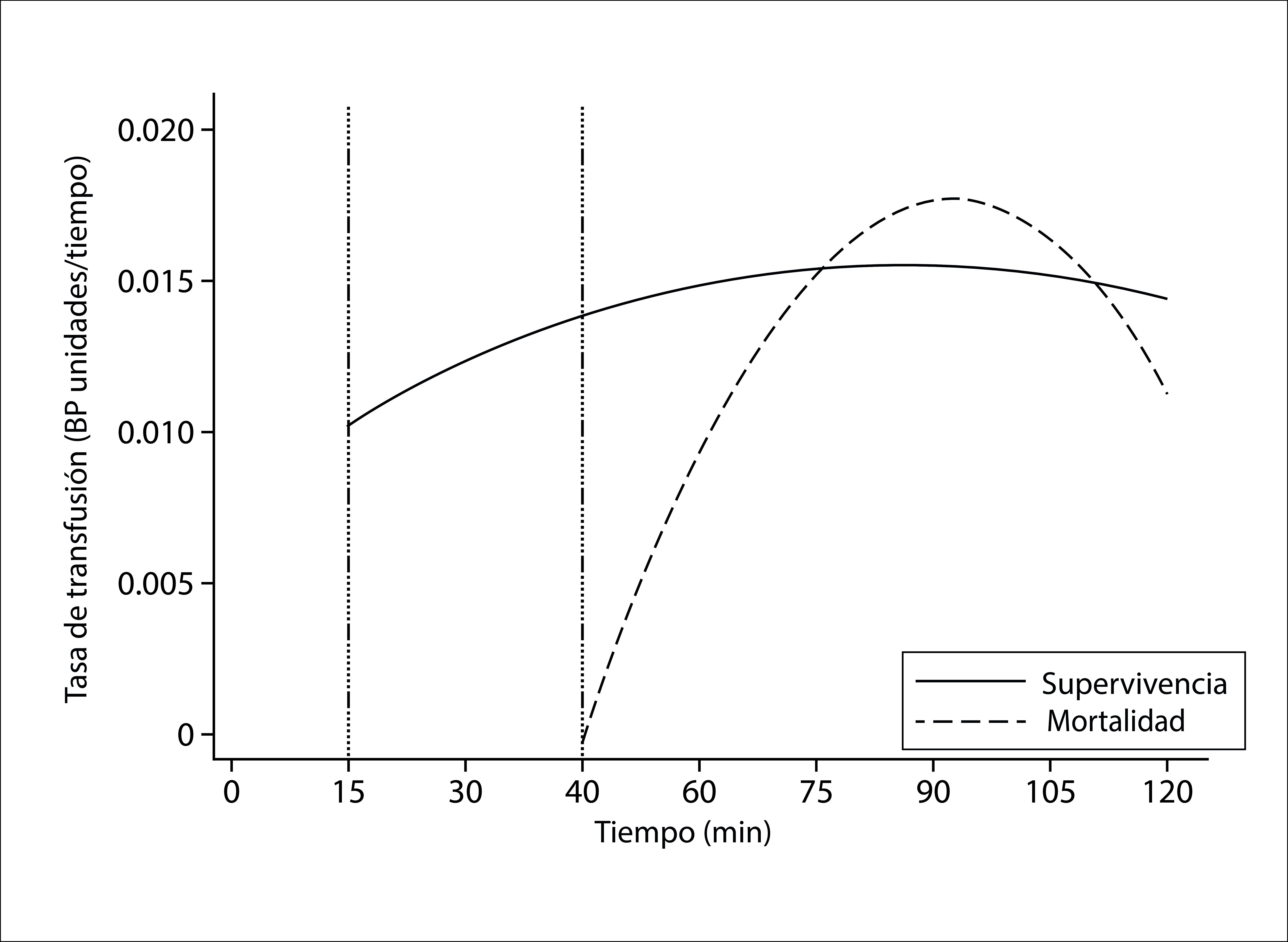

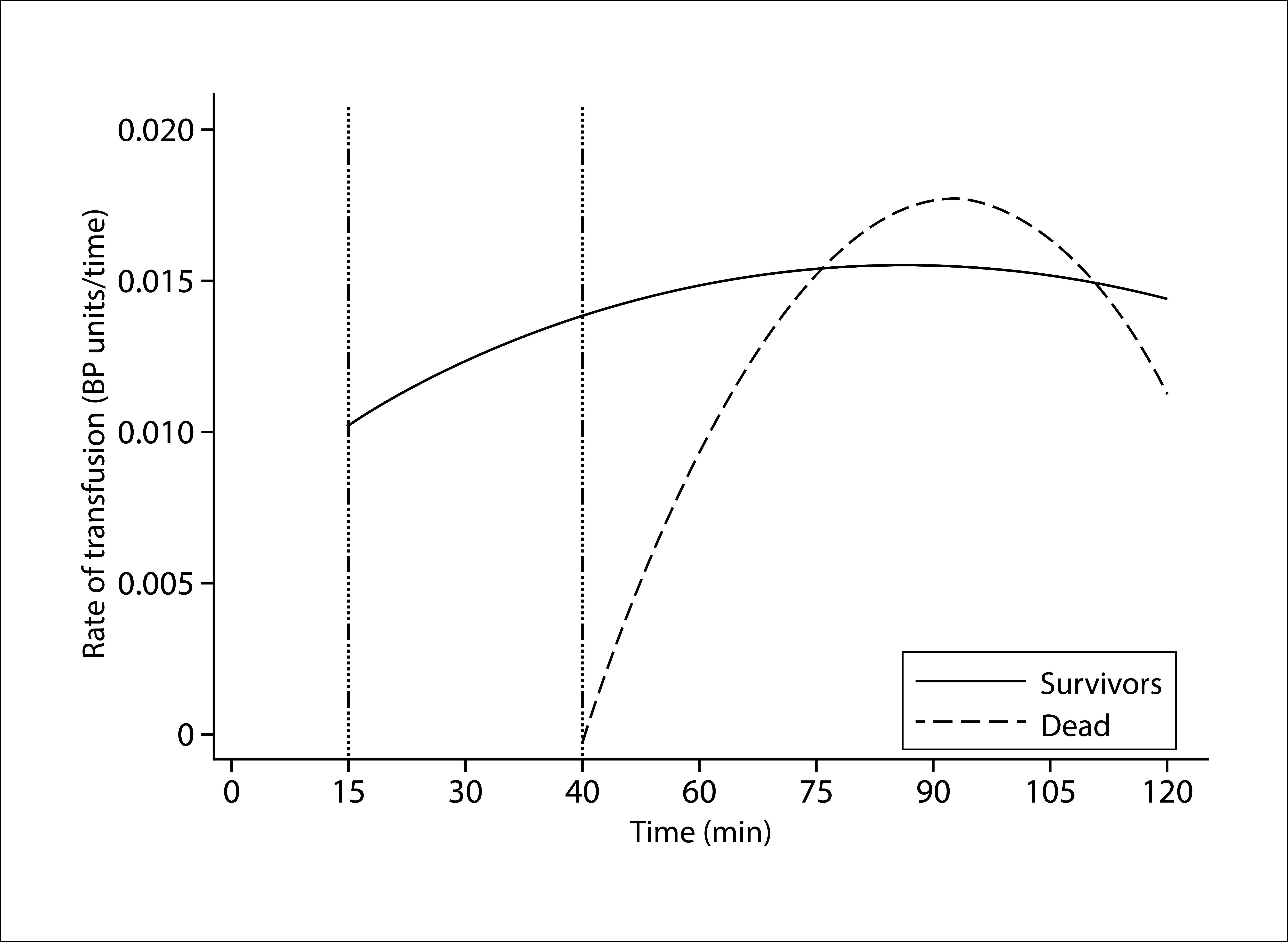

Figure 1 shows the importance of the early initiation (within 15 minutes) and administration of blood components complying with the 1: 1: 1 ratio. Through the early administration of blood components in a balanced ratio, it is possible to improve mortality and utilize fewer blood components; later initiation of a blood-based transfusion strategy is associated with higher mortality and increased number of blood components utilized 8 . Taking into account this evidence, it is easy to extrapolate the advantages of a hemostatic resuscitation strategy that utilizes whole blood, as this product can be initiated more quickly and efficiently than component therapy, thereby achieving a better outcome for patients.

Figure 1. Transfused hemocomponents rate according to surgery time (The survival of patients is associated with an earlier and constant rate of transfusion).

Which patients benefit from hemostatic resuscitation?

While only a 1-3% of patients that present to a major urban trauma center will require massive transfusion protocol, defined as the need for >10 units of blood within 24 hours, it is important to identify the patients who will benefit from early activation. This definition of massive transfusion in the literature is somewhat arbitrary and prone to survival bias 28 .

Although many surgeons rely only on clinical judgment, a study that included 10 US Level I trauma centers determined that "clinical gestalt" alone had a sensitivity of 65.6% and a specificity of 63.8% in the identification of patients who ultimately required massive transfusion; that is, it is not a reliable strategy 29 . There are various scales to assist in deciding whether or not to activate a massive transfusion protocol. We believe that the most practical scores do not require extensive calculations, making decision-making easier, using clinical assessment with rapidly available information such as blood gas and FAST. A summary of some scales to determine the probability of needing a massive transfusion is found in Table 1.

Table 1. Tools used for the prediction in hemodynamically unstable patient of massive transfusion.

| Tool | Components of the Tool | Clinical Data | Imaging Data | Laboratory Data | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Gestalt 28 | Clinical judgment of the attending surgeon | X | -- | -- | 0.62 |

| Shock Index (SI) 29 - 31 | SI >0.9 | X | -- | -- | 0.80 |

| McLaughlin 32 | Variables included: HR >105 bpm, SBP <110mmHg, Hematocrit <32%, pH <7.25 | X | -- | X | 0.84 |

| Assessment of Blood Consumption score 33 | A score of 2 or more, given 1 point for each of the following: Penetrating mechanism, HR >120 bpm, SBP <90mmHg | X | X | -- | 0.86 |

| ABCD 8 | Predicts the need for MTP if these 4 variables are present: Base excess ≥8, Blood loss>1500 ml, Hypothermia, <35° C, NISS score>35 | X | -- | X | 0.87 |

| TASH 34 | Score of >16 predicts MTP, maximum score of 27. Variables included SBP, Hemoglobin, Presence of intraabdominal fluid, Presence of complex long bone fractures or pelvic fractures, HR, Base excess, Male sex | X | X | X | 0.89 |

SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure. HR: Heart rate.

TASH: Trauma associated severe hemorrhage

ABCD: A: Airway B: Breathing C: Circulatory D: Disability

MTP: Massive transfusion protocol

If available, thrombelastography is a valuable tool for decision making in the critically ill patient with hemorrhagic shock. thrombelastography takes into account the plasma and cellular components involved in clot formation, in addition to the lysis of the clot. Thus, this tool objectively allows one to determine which element or elements are specifically driving the "vicious cycle of trauma" in each patient 30 . A summary of the elements of a thrombelastography is found in Table 2. Any deviation from normal values suggests a specific coagulation disorder. Although there is controversy in the literature about the applicability of thrombelastography in trauma patients 31 , a clinical trial in 2016 by González et al, 32 . showed that, patients who had TEG-guided resuscitation had less mortality (p: 0.049), less use of FFP (p: 0.022) and less use of platelets (p: 0.041) compared to patients who had resuscitation guided by conventional values (INR, PT, PTT, fibrinogen).

Table 2. Summary of the critical elements of a thrombelastography 38 .

| Phase of Coagulation | TEG Parameter | Normal Range | Description | Interpretation in a Hypocoagulable Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activation | R time | 5-10 minutes | Time period from the start of the test until the initial clot formation | If R time >10 minutes, consider: FFP, prothrombin complex, anticoagulant reversal |

| Amplification | K time | 1-3 minutes | Time from beginning of clot formation to reaching a certain strength, specifically an amplitude of 20mm | If K time >3 minutes, consider: Fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate |

| Propagation | α angle | 53.0-70.0mm | Angle between R and the imaginary line from the initial clot formation to the point of maximum strength related to the K time | If α angle <53mm, consider: Fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate |

| Termination | MA angle | 50-70mm | Highest point on the curve that represents the maximum clot strength | Si MA <50mm, consider: Platelets |

| Fibrinolysis | LY30 | 0-3% | Percentage of reduction in amplitude 30 minutes after the MA | If LY30 >3%, consider: Tranexamic acid |

TEG: thrombelastography

The evidence for whole blood

The goal of 1:1:1 resuscitation is to return to the patient in hemorrhagic shock what has been lost whole blood. While level 1 evidence is lacking, studies in the last decade suggest that damage control resuscitation should move from mimicking whole blood to transfusing it 4 , 12 .

Whole blood confers numerous practical advantages over component therapy. Whole blood returns blood to the hemorrhaging patient in a physiologic ratio. Each component unit contains an increased amount of anticoagulants and additives that contribute to a patient’s overall coagulopathy compared to one unit of whole blood 33 . One study found that 825 mL of anticoagulants and additives transfused in the first 24 hours increased the risk of dilutional coagulopathy 34 . Hess et al. 12 , 35 , found that reconstituted whole blood via components in a 1:1:1 ratio yielded a dilute mixture with a hematocrit of 29%, platelet count of 90,000, and coagulation factors diluted to 62% of whole blood concentrations. Stored whole blood, depending on duration of storage, has been shown to have a hematocrit 35-38%, platelet count of 150,000-200,000 and coagulation factors present at approximately 85% of pre-donation values 12 . The use of whole blood in the prehospital environment is ideal as whole blood is significantly easier to transport and administer than component therapy (Table 3).

Table 3. The benefits of whole blood compared to component therapy at our institution 37 .

| Components | Whole Blood |

|---|---|

| Larger volume of additives and anticoagulants | Less volume of additives and anticoagulants |

| Requires transfusion of 3 bags | Requires transfusion of 1 bag |

| Applicable in few hospitals worldwide | Easy to replicate |

| Less accessible inresource-limited environment or in resource limited settings | Easy to implement in the prehospital environment and resources limited settings |

| More expensive | Cheaper |

With an increase in surgical patient volume at the Trauma and Acute Care Surgery service at Hospital Vicente Corral Moscoso in Southern Ecuador 36 , a whole blood program was implemented for the resuscitation of these critical patients. Whole blood is collected from donors, screened and available to surgical services for 48 hours, after which it is fractionated into components. Packed red blood cells and FFP are available, but platelets are sent to the local cancer hospital and are not available for transfusion after fractionation. Prior to the implementation of the whole blood program at our institution, pRBCs and FFP were available on an inconsistent and variable basis; platelets were rarely, if ever, available. We have recently demonstrated the feasibility of this strategy in a series of 93 patients who suffered hemorrhagic shock due to trauma or obstetric emergencies 37 .

Mortality

Evidence from the military literature in the United States from recent conflicts in the Middle East have focused primarily on fresh whole blood, as combat scenarios necessitate the collection from prescreened donors in a “walking blood bank” on an emergency basis. Fresh whole blood (FWB) is typically stored at room temperature and used within 72 hours of collection, usually without prior refrigeration 12 . In a retrospective study, Spinella et al. 33 , described an improvement in 24-hour and 30-day mortality (p: 0.002) in patients resuscitated with fresh whole blood in addition to pRBCs and FFP, compared to component therapy, including apheresis platelets. The fresh whole blood group, however, had a significantly lower temperature on admission compared to the component therapy group and had a higher incidence of requiring massive transfusion 33 . However, Perkins et al. 38 , described an increase in 24-hour survival in the fresh whole blood group that approached significance (p= 0.06), with no difference in 30-day mortality. In this study, the fresh whole blood group presented with a higher ISS and a lower TRISS than the group treated with component therapy. Similarly, Nessen et al. 39 , found that fresh whole blood was associated with better survival compared to pRBCs and FFP alone (OR: 0.096, 95% CI: 0.02-0.53), despite the fresh whole blood group having higher ISS and respiratory rate, and a lower SBP and temperature on admission than the group managed with component therapy. A prospective civilian study in Australia, comparing fresh whole blood and component therapy in patients from various surgical specialties requiring massive transfusion, found no difference in 24-hour or 30-day mortality with no significant difference in baseline characteristics in the two groups 40 .

However, the civilian sector has been focused on stored whole blood largely due to the infectious concerns related to transfusion of fresh whole blood. Stored whole blood is kept at 1-6° C for up to 21 or 35 days depending on the anticoagulant used to sustain the red blood cell integrity 12 . Civil studies predominantly demonstrate the equivalence or superiority of whole blood over component therapy. A single-institution randomized control trial compared modified whole blood (leuko-reduced whole blood with additional platelet transfusion) with component therapy, and did not find any difference in 24-hour or 30-day mortality. However, the researchers did not initially exclude traumatic brain injury patients from the study. Most deaths in the modified whole blood arm occurred due to traumatic brain injury 41 . In a retrospective study using historical controls, a decrease in trauma mortality was observed in patients treated with stored whole blood (8.8% in component therapy versus 2.2% with stored whole blood, p: 0.039), with no difference in 30-day mortality 42 . A recent prospective trial conducted in prehospital and emergency room settings found on multivariate analysis that low titer group O whole blood transfusion was an independent predictor of longer 30-day survival, despite the fact that patients receiving low-titer group O whole blood presented with evidence of more severe shock since they had a lower pH, worse base deficit and higher lactate than those in the component therapy group 43 .

Use of blood products

Some studies do not describe differences in blood product utilization rates among whole blood-treated patients compared to those managed with component therapy 40 , 42 , 44 , 45 . While the study by Cotton et al. found no differences in the use of components at 24 hours, there was a trend towards a lower use of plasma and platelets in the first three hours in the group managed with modified whole blood (p: 0.11 whole blood p: 0.08, respectively) 41 The recent evaluation of prehospital and emergency room whole blood administration found up to a 50% reduction in the use of blood products after leaving the emergency room in those patients managed with whole blood transfusion 43 .

Role of autotransfusion

In centers where whole blood may not be available, autotransfusion provides an attractive alternative. A study of 272 patients at two level I trauma centers demonstrated that autotransfusion from the hemithorax in trauma patients was associated with no difference in complications and a significant decrease in use of packed red blood cells (p: 0.01) and platelets (p: 0.01), as well as decreased overall cost (p: 0.01). In the process of autotransfusion, blood is suctioned from the patient into a collection system with citrate phosphate dextrose solution, after which the anticoagulated product is transfused directly back to the patient without necessitating a type and cross 46 . Similarly, Folkersen et al. 47 , described a significant decrease in the units of red blood cells (p: 0.11) and decreased postoperative drainage (p: 0.032) in cardiac surgery patients treated with reinfusion of shed mediastinal blood.

Hemostatic capacity of whole blood

Much of the reluctance to accept whole blood in civilian centers is the concern regarding the hemostatic efficacy of cold-stored platelets and the risk of transfusion reactions in non-group O recipients of group-O whole blood. The American Association of Blood Banks (AABB) standards recommend that platelets be stored at 22-24° C with continuous gentle agitation for a maximum of 5 days. The reasoning behind this policy is that platelets best retain their function after transfusion under these conditions. Room temperature storage, however, increases the chance of bacterial contamination and leads to a decline in platelet function due to a decrease in pH associated with persistent metabolic activity 48 . New studies suggest that cold-stored platelets retain hemostatic function for up to 21 days and that refrigerated platelets may achieve hemostasis more effectively than room-temperature platelets 12 .

The Trauma and Emergency Surgery group in Cali, Colombia, has recently completed a whole blood validation project, using a platelet-sparing leukoreduction system, whereby the hemostatic capacity of whole blood is compared ex vivo to component therapy. Twenty units of whole blood from young, male and nulliparous female donors was performed. Blood was stored in refrigeration without agitation at 2-8° C. While hemoglobin and hematocrit remained stable, platelet count decreased in the first 6 days; the platelet count, however, remained above 100,000 per microliter. In this same timeframe, clotting factors, fibrinogen and protein C remained in normal ranges. Its hemostatic property was also evaluated by thrombelastography, which demonstrated a slight prolongation in the initiation of the clot, but stable clot formation throughout. These preliminary results are the basis for the development of the WEBSTER randomized control clinical trial which will test this whole blood system, pioneering the application of whole blood in civilian trauma 49 .

Safety of whole blood

At the Hospital Vicente Corral Moscoso in Southern Ecuador, group-O whole blood that is untitered and non-leukoreduced is available for surgical patients presenting in hemorrhagic shock. In a recent series of 93 patients in hemorrhagic shock in the trauma or obstetrics and gynecology services, no symptomatology consistent with that of a hemolytic transfusion reaction was observed 37 .

Several studies have demonstrated no statistically significant difference in the rate of transfusion reactions occurring in recipients of LTOWB compared to component therapy. In comparing patients resuscitated with LTOWB and component therapy, no statistically significant difference is described in rates of hemolysis and transfusion, 42 , 44 , with one possible case of transfusion related circulatory overload (TACO) in a patient transfused with LTOWB 42 . No change in hemolysis markers has been documented with the administration of up to 4 units of whole blood 43 , 45 , 50 .

Conclusion

Resuscitation of patients presenting in hemorrhagic shock due to trauma has evolved from the administration of high volumes of crystalloid to the concept of hemostatic resuscitation. In damage control resuscitation, the gold standard for resuscitation is a balanced component therapy with a 1:1:1 ratio. This strategy attempts to imitate the composition of the fluid that has been lost, shining light on the new proposals for the use of whole blood in hemostatic resuscitation.

References

- 1.Eastridge BJ, Holcomb JB, Shackelford S. Outcomes of traumatic hemorrhagic shock and the epidemiology of preventable death from injury. Transfusion. 2019;59(S2):1423–1428. doi: 10.1111/trf.15161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, Fox EE, Wade CE, Podbielski JM. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1 1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(5):471–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore SE, Decker A, Hubbard A, Callcut RA, Fox EE, Del Junco DJ. Statistical Machines for Trauma Hospital Outcomes Research Application to the PRospective, Observational, Multi-Center Major Trauma Transfusion (PROMMTT) Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spinella PC, Pidcoke HF, Strandenes G, Hervig T, Fisher A, Jenkins D. Whole blood for hemostatic resuscitation of major bleeding. Transfusion. 2016;56(2):S190–S202. doi: 10.1111/trf.13491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cap AP, Pidcoke HF, Spinella P, Strandenes G, Borgman MA, Schreiber M. Damage Control Resuscitation. Mil Med. 2018;183(Suppl 2):36–43. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang R, Holcomb JB. Optimal Fluid Therapy for Traumatic Hemorrhagic Shock. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(1):15–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolley T, Thompson P, Kirkman E, Reed R, Ausset S, Beckett A. Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research Network position paper on the role of hypotensive resuscitation as part of remote damage control resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(6S Suppl 1):S3–S13. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ordoñez CA, Badiel M, Pino LF, Salamea JC, Loaiza JH, Parra MW. Damage control resuscitation early decision strategies in abdominal gunshot wounds using an easy “ABCD” mnemonic. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5):1074–1078. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31826fc780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holcomb JB, Fox EE, Wade CE, Group PS. The PRospective Observational Multicenter Major Trauma Transfusion (PROMMTT) study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(1 Suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182983876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JB, Guyette FX, Neal MD, Claridge JA, Daley BJ, Harbrecht BG. Taking the Blood Bank to the Field The Design and Rationale of the Prehospital Air Medical Plasma (PAMPer) Trial. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19(3):343–350. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2014.995851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spinella PC, Cap AP. Whole blood back to the future. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016;23(6):536–542. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cap AP, Beckett A, Benov A, Borgman M, Chen J, Corley JB. Whole Blood Transfusion. Mil Med. 2018;183(suppl_2):44–51. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muñoz-Valencia A, Bonilla-Escobar F, Puyana JC. Effect of blood bank availability on mortality due to shock after trauma in a middle-income country. San Francisco, CA: American College of Surgeons; 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts N, James S, Delaney M, Fitzmaurice C. The global need and availability of blood products a modelling study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(12):e606–ee15. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The World Health Organization Blood safety and availability. 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blood-safety-and-availability

- 16.Pan American Health Association . Latin America and the Caribbean approaching half-way mark toward goal of 100% voluntary blood donation. Pan American Health Association; 2016. https://www.paho.org/salud-en-las-americas-2017/?tag=en [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan American Health Organization . Supply of Blood for Transfusion in Latin American and Caribbean Countries 2014 and 2015. Washington D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLeod JB, Lynn M, McKenney MG, Cohn SM, Murtha M. Early coagulopathy predicts mortality in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55(1):39–44. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000075338.21177.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kushimoto S, Kudo D, Kawazoe Y. Acute traumatic coagulopathy and trauma-induced coagulopathy: an overview. J Intensive Care. 2017;5(6) doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizobata Y. Damage control resuscitation: a practical approach for severely hemorrhagic patients and its effects on trauma surgery. J Intensive Care. 2017;5(4) doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ditzel RM, Anderson JL, Eisenhart WJ, Rankin CJ, DeFeo DR, Oak S. A review of transfusion- and trauma-induced hypocalcemia Is it time to change the lethal triad to the lethal diamond? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(3):434–439. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ordoñez CA, Parra MW, Serna JJ, Rodríguez HF, García AF, Salcedo A. Damage Control Resuscitation : REBOA as the New Fourth pillar. Colomb Med (Cali) 2020;51(4):e–4014353. doi: 10.25100/cm.v51i4.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Kram HB, Waxman K, Lee TS. Prospective trial of supranormal values of survivors as therapeutic goals in high-risk surgical patients. Chest. 1988;94(6):1176–1186. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.6.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasotakis G, Sideris A, Yang Y, de Moya M, Alam H, King DR. Aggressive early crystalloid resuscitation adversely affects outcomes in adult blunt trauma patients an analysis of the Glue Grant database. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(5):1215–1221. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182826e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bickell WH, Wall MJ, Pepe PE, Martin RR, Ginger VF, Allen MK. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(17):1105–1109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ley EJ, Clond MA, Srour MK, Barnajian M, Mirocha J, Margulies DR. Emergency department crystalloid resuscitation of 1 5 L or more is associated with increased mortality in elderly and nonelderly trauma patients. J Trauma. 2011;70(2):398–400. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318208f99b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgman MA, Spinella PC, Perkins JG, Grathwohl KW, Repine T, Beekley AC. The ratio of blood products transfused affects mortality in patients receiving massive transfusions at a combat support hospital. J Trauma. 2007;63(4):805–813. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181271ba3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savage SA, Zarzaur BL, Croce MA, Fabian TC. Redefining massive transfusion when every second counts. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(2):396–400. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827a3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pommerening MJ, Goodman MD, Holcomb JB, Wade CE, Fox EE, Del Junco DJ. Clinical gestalt and the prediction of massive transfusion after trauma. Injury. 2015;46(5):807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson PI, Stissing T, Bochsen L, Ostrowski SR. Thrombelastography and tromboelastometry in assessing coagulopathy in trauma. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:45–45. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt H, Stanworth S, Curry N, Woolley T, Cooper C, Ukoumunne O, et al. Thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) for trauma induced coagulopathy in adult trauma patients with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD010438. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010438.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez E, Moore EE, Moore HB. Management of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy with Thrombelastography. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(1):119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinella PC, Perkins JG, Grathwohl KW, Beekley AC, Holcomb JB. Warm fresh whole blood is independently associated with improved survival for patients with combat-related traumatic injuries. J Trauma. 2009;66(4 Suppl):S69–S76. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819d85fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yazer MH, Cap AP, Spinella PC. Raising the standards on whole blood. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(6S Suppl 1):S14–SS7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hess JR. Resuscitation of trauma-induced coagulopathy. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:664–667. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarmiento Altamirano D, Himmler A, Chango Sigüenza O, Pino Andrade R, Flores Lazo N, Reinoso Naranjo J, et al. The successful implementation of a trauma and acute care surgery model in Ecuador. World J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Himmler A, Galarza M, Reinoso J, Peña S, Sarmiento D, Flores N, et al. Is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? The implementation and outcomes of a whole blood program in Ecuador. Res Sq. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-66244/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perkins JG, Cap AP, Spinella PC, Shorr AF, Beekley AC, Grathwohl KW. Comparison of platelet transfusion as fresh whole blood versus apheresis platelets for massively transfused combat trauma patients (CME) Transfusion. 2011;51(2):242–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nessen SC, Eastridge BJ, Cronk D, Craig RM, Berséus O, Ellison R. Fresh whole blood use by forward surgical teams in Afghanistan is associated with improved survival compared to component therapy without platelets. Transfusion. 2013;53(1):107S–113S. doi: 10.1111/trf.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho KM, Leonard AD. Lack of effect of unrefrigerated young whole blood transfusion on patient outcomes after massive transfusion in a civilian setting. Transfusion. 2011;51(8):1669–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cotton BA, Podbielski J, Camp E, Welch T, del Junco D, Bai Y. A randomized controlled pilot trial of modified whole blood versus component therapy in severely injured patients requiring large volume transfusions. Ann Surg. 2013;258(4):527–532. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a4ffa0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazelton JP, Cannon JW, Zatorski C, Roman JS, Moore SA, Young AJ. Cold-stored whole blood A better method of trauma resuscitation? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(5):1035–1041. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams J, Merutka N, Meyer D, Bai Y, Prater S, Cabrera R. Safety profile and impact of low-titer group O whole blood for emergency use in trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(1):87–93. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yazer MH, Jackson B, Sperry JL, Alarcon L, Triulzi DJ, Murdock AD. Initial safety and feasibility of cold-stored uncrossmatched whole blood transfusion in civilian trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seheult JN, Anto V, Alarcon LH, Sperry JL, Triulzi DJ, Yazer MH. Clinical outcomes among low-titer group O whole blood recipients compared to recipients of conventional components in civilian trauma resuscitation. Transfusion. 2018;58(8):1838–1845. doi: 10.1111/trf.14779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhee P, Inaba K, Pandit V, Khalil M, Siboni S, Vercruysse G. Early autologous fresh whole blood transfusion leads to less allogeneic transfusions and is safe. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(4):729–734. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Folkersen L, Tang M, Grunnet N, Jakobsen CJ. Transfusion of shed mediastinal blood reduces the use of allogenic blood transfusion without increasing complications. Perfusion. 2011;26(2):145–150. doi: 10.1177/0267659110393299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bahr MP, Yazer MH, Triulzi DJ, Collins RA. Whole blood for the acutely haemorrhaging civilian trauma patient a novel idea or rediscovery? Transfus Med. 2016;26(6):406–414. doi: 10.1111/tme.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macia C, Guzmán M, Hernández E, Alcala M, García A, Caicedo Y. Whole blood prepared via a platelet-sparing leukoreduction filtration system preserves the hemostatic function for 21 days early results of a pilot study to expand the use of whole blood for trauma in South America. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231:e64. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.08.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seheult JN, Triulzi DJ, Alarcon LH, Sperry JL, Murdock A, Yazer MH. Measurement of haemolysis markers following transfusion of uncrossmatched, low-titre, group O+ whole blood in civilian trauma patients initial experience at a level 1 trauma centre. Transfus Med. 2017;27(1):30–35. doi: 10.1111/tme.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]