Abstract

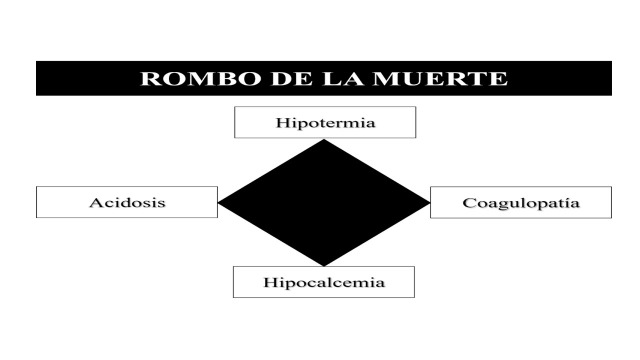

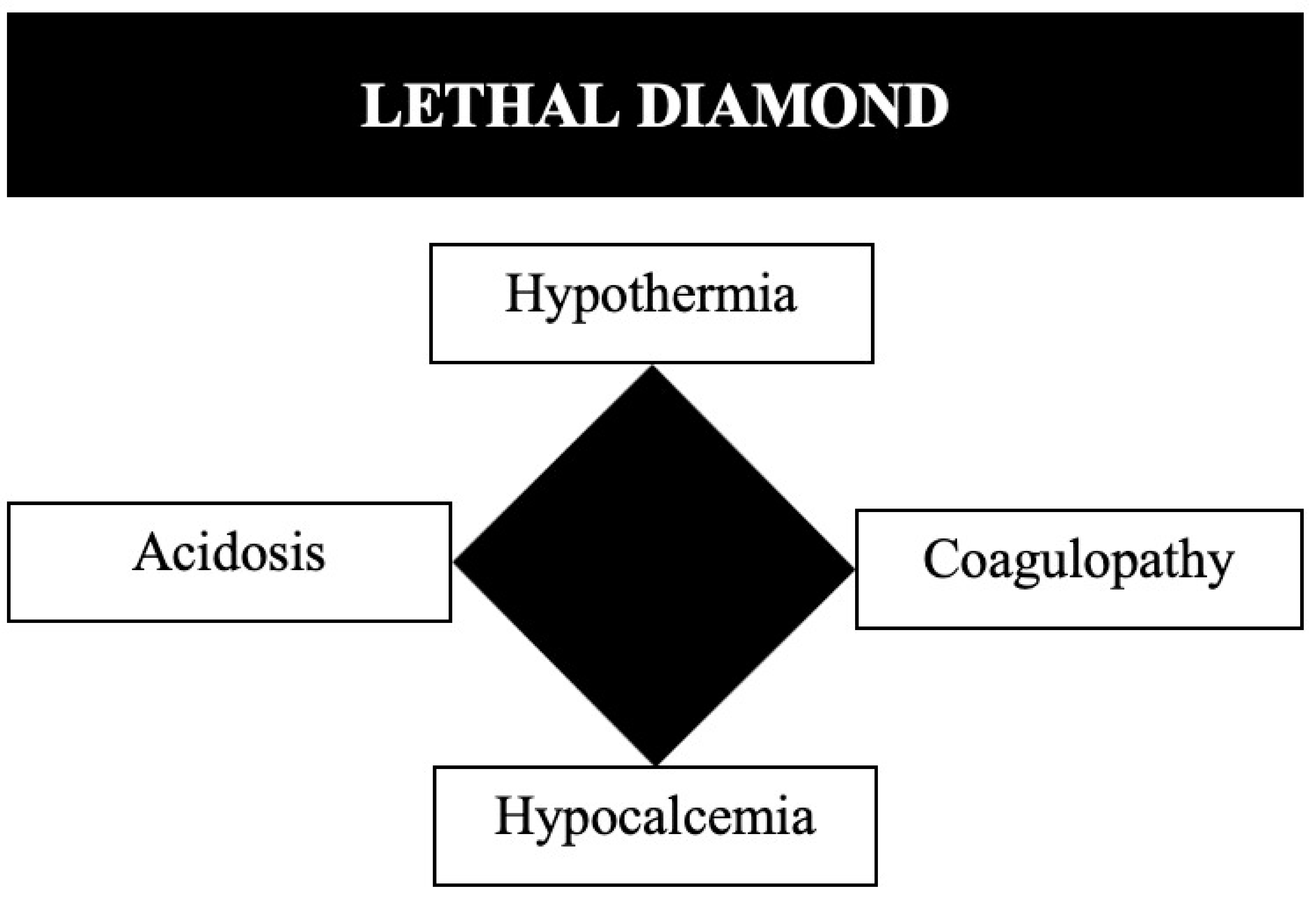

Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) seeks to combat metabolic decompensation of the severely injured trauma patient by battling on three major fronts: Permissive Hypotension, Hemostatic Resuscitation, and Damage Control Surgery (DCS). The aim of this article is to perform a review of the history of DCR/DCS and to propose a new paradigm that has emerged from the recent advancements in endovascular technology: The Resuscitative Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA). Thanks to the advances in technology, a bridge has been created between Pre-hospital Management and the Control of Bleeding described in Stage I of DCS which is the inclusion and placement of a REBOA. We have been able to show that REBOA is not only a tool that aids in the control of hemorrhage, it is also a vital tool in the hemodynamic resuscitation of a severely injured blunt and/or penetrating trauma patient. That is why we propose a new paradigm “The Fourth Pillar”: Permissive Hypotension, Hemostatic Resuscitation, Damage Control Surgery and REBOA.

Keywords: Hemorrhage, Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, REBOA

Resumen

La resucitación en control de daños busca combatir la descompensación metabólica del paciente severamente traumatizado mediante tres ejes: la hipotensión permisiva, la resucitación hemostática y la cirugía de control de daños. El objetivo de este artículo es hacer una revisión de la historia de la resucitación en control de daños y la cirugía de control de daños proponiendo un nuevo paradigma basado en los recientes avances de la tecnología endovascular. Un puente ha sido creado entre el manejo prehospitalario y el control del sangrado, descrito antes de la etapa I de la cirugía de control de daños, que es la inclusión y colocación de un REBOA. Esta es una herramienta adicional en el control de la hemorragia y de soporte en la resucitación hemodinámica de los pacientes con trauma severo de tipo cerrado y/o penetrante. Por lo que se propone un nuevo paradigma “El cuarto pilar”: Hipotensión permisiva, resucitación hemostática, cirugía de control de daños y REBOA.

Palabras clave: Cirugía de control de daños, REBOA, resucitación en control de daños, rombo de la muerte

Introduction

Damage Control Surgery (DCS) is a strategy for the management of patients with severe trauma, these patients face a giant metabolic challenge given the severity of their injury and blood loss. The main surgical goal of DCS is to be a bridge between hemorrhage control and patient recovery. The aim of this article is to perform a review of the history of DCS and to propose a new paradigm that has emerged from the recent advancements in endovascular technology: The Resuscitative Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA). This article is a consensus that synthesizes the experience earned during the past 30 years in trauma critical care management of the severely injured patient from the Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group (CTE) of Cali, Colombia which is made up of experts from the University Hospital Fundación Valle del Lili, the University Hospital del Valle "Evaristo García", Universidad del Valle and Universidad Icesi, Colombian Association of Surgery, the Pan-American Trauma Society and the collaboration of international specialists of the United States of America.

History

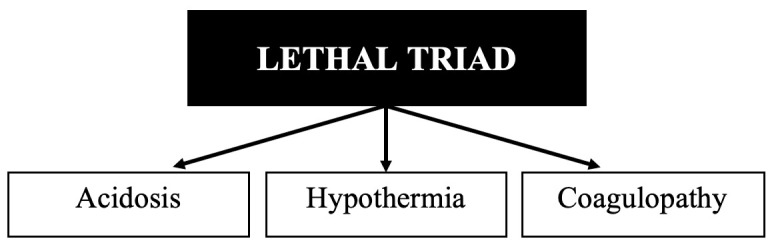

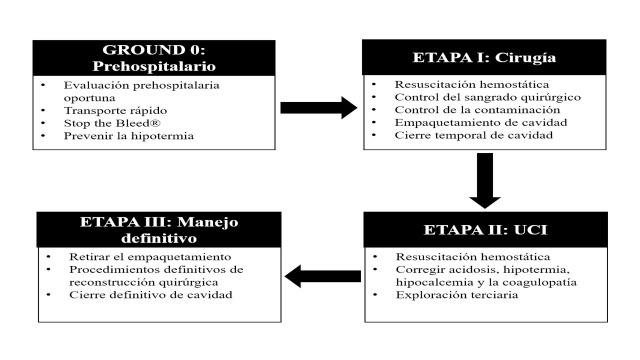

During the second half of the XX century, surgeons exposed to trauma performed aggressive and definitive surgical management of their patients that required in most cases long complex anatomical repairs. Exsanguination, massive volume resuscitation, and subsequent inflammatory responses triggered a metabolic failure that is now known as the lethal triad: acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Lethal Triad.

However, there were experiences contrary to this position that only until the 1980's were coined “abbreviated laparotomies” by Stone et al, which consisted of early termination of abdominal surgeries. This subsequently was morphed into the concept of “staged management” in which intra-abdominal packing was introduced accompanied by delayed surgical completion after correcting the patients' coagulopathy 1 . At the time this newly devised concept was revolutionary and controversial although survival rates were >50% 2 - 6 . Dr. Rotondo in 1993 used the term "damage control", an expression taken from the US Navy associated with the ability to absorb and repair a damaged warship without interrupting the mission and eventually docking the vessel to the nearest port for definitive repairs 5 . He applied this concept to a group of exsanguinating patients in three specific stages 7 :

Stage I: Control of bleeding and / or contamination, abdominal packing and temporary cavity closure.

Stage II: Resuscitation and physiologic restoration.

Stage III: Re-exploration, treatment and definitive closure.

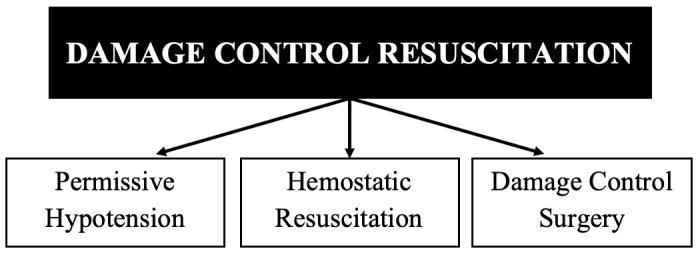

The initial reported overall survival rate was 58% which caused the medical community of the time to reflect on its utility. An example of such reflections was Johnson et al, who added a Stage 0 also known as Ground Zero in which prehospital management and early triage of these patients were included 6 , 8 . This was the beginning of a conceptual revolution in trauma surgery that included the importance of a balanced resuscitation which was later named Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) 9 - 11 . DCR seeks to combat metabolic decompensation of the severely injured trauma patient by battling three major fronts: Permissive Hypotension, Hemostatic Resuscitation, and Damage Control Surgery (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Damage Control Resuscitation: Classic Description.

Damage control resuscitation

Permissive hypotension

The aim of this concept is to keep the blood pressure low enough to avoid dislodging a potentially forming soft blood clot at the site of traumatic hemorrhage and/or minimize the blood loss from it but high enough to continue to perfuse vital organs. Cannon and Fraser in 1918 stated that if the blood pressure rises before the surgeon was ready to control the source of bleeding then the blood that is badly needed to maintain life may be lost 10 . This concept was placed in practice and reinforced by Beecher during World War II, calling it "hypotensive resuscitation" with the recommendation of maintaining a systolic blood pressure (SBP) between 70 and 80 mmHg before definitive surgical repair 9 . Bickel and Mattox described in 1994 that resuscitating with low volumes of crystalloids in combination with permissive hypotension with a set SBP goal between 70-90 mmHg was associated with decreased mortality and adverse events 12 .

Hemostatic resuscitation

Deliberate administration of large volumes of crystalloids and packed red blood cells intravenously have been found to exacerbate coagulopathy in patients with severe trauma promoting ongoing bleeding 13 . It is currently recommended that volumetric restoration of blood loss should be achieved via a 1: 1: 1: 1 blood component ratio of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets and cryoprecipitates 14 , 15 . This strategy has shown to decrease mortality from 65% to about 19% and also decreases the overall incidence of complications including the chances of rebleeding and sepsis 16 , 17 . The following goals of blood loss replacement are sought:

Hemoglobin of ≥ 8g / dL

Platelet count ≥100,000 / dL

Normalization of coagulation times (Thromboelastography / Rotational Thromboelastometry)

Fibrinogen >100 mg / dL

Furthermore, from the recent US conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan the military concept of whole blood transfusion has re-emerged but has had huge hurdles in its translation to civilian trauma centers because of the technical, logistical and business model difficulties that this concept implies to regional civilian blood banks 18 , 19 . On this subject, the Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group (CTE) of Cali, Colombia have been leading the crusade in Latin America and the World that whole blood contains all the essential components including red blood cells, clotting factors, and platelets which in turn can provide an effective hemostatic capacity to meet the transfusion needs of a patient with ongoing hemorrhage. Thus, whole blood applied in civilian trauma centers may in turn decrease total blood usage and complications related to massive blood transfusions 20 , 21 .

Fifty five percent of all trauma patients that are brought to a treating facility have hypocalcemia prior to receiving any kind of blood transfusion 22 . This pre-existing trauma state of hypocalcemia is potentially aggravated by initial management via a DCR in which blood and blood products are transfused, because these units are typically stored in local blood banks using citrate which in turn chelates ionized calcium in the bloodstream. The early management of hypocalcemia in trauma patients may be of more significance than previously believed because as serum calcium levels drop, coagulopathy occurs, which can lead to continued hemorrhage and possible death. Ditzel and Anderson 23 have recently included the concept of hypocalcemia as a new component of the classic lethal triad and so creating the new “Lethal Diamond” (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Lethal Diamond.

Damage control surgery

Principles

DCS is a strategy that safeguards the trauma patients physiological reserve but it can also be potentially harmful in cases that do not meet the true indications for its use 24 - 26 . It can be applied to any compromise body cavity including chest, abdomen, pelvis, extremities, among others. This strategy is not only an intra-operative clinical decision, it must start with a series of simultaneous interventions from the identification of the patient at the scene of the accident or incident which include:

Penetrating and/or blunt trauma with initial SBP < 90 mm Hg

Major trauma with an estimated blood loss > 1200 ml

Inability to control bleeding by direct pressure, wound packing and/or tourniquet (Stop the Bleed®)

Worsening acidosis, hypothermia, hypocalcemia and/or coagulopathy

These criteria are not exclusive at the prehospital scenario but also can be applied in the ER/Trauma bay and the operating room (OR). Once the patient is under the trauma team’s care, the criteria that may influence the implementation of DCS are:

Inability to control surgical bleeding

Inability to close the body cavity without creating associated intra-cavitary hypertension due to massive visceral edema

Definitive surgical management exceeds intraoperative time restraints

Philosophy

DCS requires not only the coordination of various participants in order to contain the injury and prevent the lethal diamond of death (acidosis, hypothermia, coagulopathy and hypocalcemia), it also requires a complete re-thinking on their behalf. They must constantly anticipate the repercussions of potential injuries and at the same time recognize the metabolic demand of the trauma victim that is fighting for his or her life 27 . This change of thinking is a holistic vision towards the problem which include:

Asking for assistance when required, which indicates good judgment

Definitive surgical management is not the ultimate goal instead the goal should be control of all surgical bleeding, bowel contamination and the restoration of normal physiology

The application of a four-stage approach aimed at preventing the deadly cascade of events that will culminate in the patient’s death

The four stages of DCS

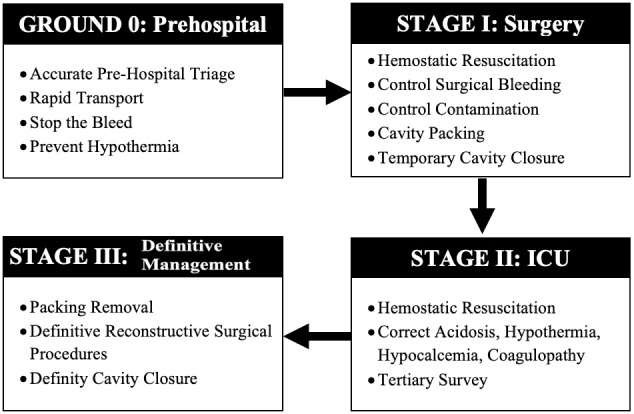

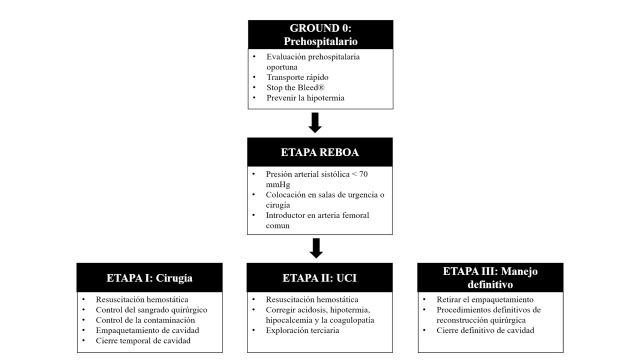

As previously stated, DCS is divided into four classic stages which are (Figure 4):

Figure 4. The Four Stages of DCS.

Ground 0: Prehospital Management

At the trauma scene, the evaluation begins with the "ABCDE" proposed by the American College of Surgeons in their Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) course, in which the initial triage of the severely injured victim is recognized and the concept of “pick and run” is applied to achieve optimal transport times. Also, the principles of “Stop the bleed ®” by the American College of Surgeons and the Committee on Trauma which include the recognition and control of life-threatening hemorrhage via direct pressure, wound packing and/or tourniquet application. Upon arrival to the Emergency Room (ER) / Trauma Center, a multidisciplinary team rapidly corroborates the initial prehospital evaluation and establishes the clinical management algorithm to be followed and whether the patient is or is not a candidate for DCS 6 . If so, balanced blood product resuscitation is initiated and the patient is moved quickly to the OR.

Stage I: Control of Bleeding and Contamination

A process of containment of the injury begins in the OR. The objective of the first surgical intervention is to control the sources of surgical bleeding and to carry out quick brief interventions which include packing, vessel ligation, temporary shunts and balloon tamponading among others to achieve this goal 28 - 30 . Hollow viscus injuries are also addressed during this initial surgical intervention and controlled also via simple procedures such as transection and ligation of ends. The surgeon must be aware that he or she is in a race against time due to the impending on slot of the diamond of death upon the patient, limiting the initial operative procedure to 60 and up to 120 minutes 31 , 32 . A temporary closure of the inflicted cavity should follow with a negative pressure system and the patient should be immediately transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for rewarming, correction of coagulopathy, hypocalcemia and acidosis 33 .

Stage II: ICU Management

Hemodynamic recovery of the severely injured patient requires several measures which have been initiated in the ER/OR and are continued in the ICU. These include implementation of DCR at a 1: 1: 1: 1 transfusion ratio of blood products plus the addition of tranexamic acid, hypothermia prevention maneuvers and close hemodynamic monitoring 34 . A tertiary review of the patient is completed with imaging studies, if needed, to rule out or assist in the control of ongoing critical injuries that need to be addressed. Also, continuous monitoring of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) in the ICU is essential to avoid the development of both intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) even in the trauma patient with an open abdomen. This preventative measure ultimately increases the patient’s overall survival after DCS 35 .

Stage III: Definitive Surgical Management

When the initial ICU goals of DCR have been achieved, then the patient should be taken back to the OR for packing removal, cavity washout, definitive vascular, solid and/or hollow viscus injury repair and permanent cavity closure 36 . However, the return to the OR may occur under a planned situation as previously described or as an unplanned scenario in which ongoing hemodynamic instability persists which is usually secondary to ongoing uncontrolled surgical bleeding, missed hollow viscus injury or a developing compartment syndrome that can develop even in patients with an open cavity. Obviously, the ideal is to return to the OR in a planned controlled manner which usually is within the first 24 to 48 hours once the resuscitation efforts performed aggressively in the ICU have restored the homeostasis of the patient 31 , 37 .

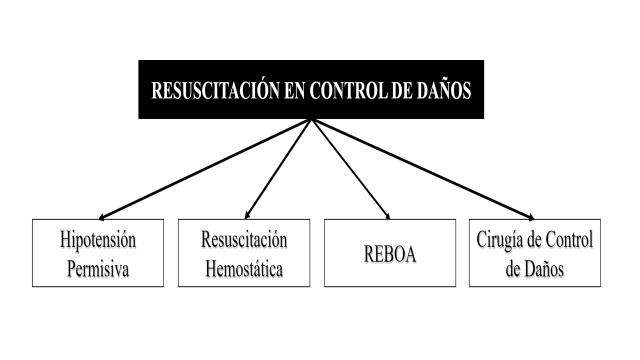

Stage: REBOA Resuscitative Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta

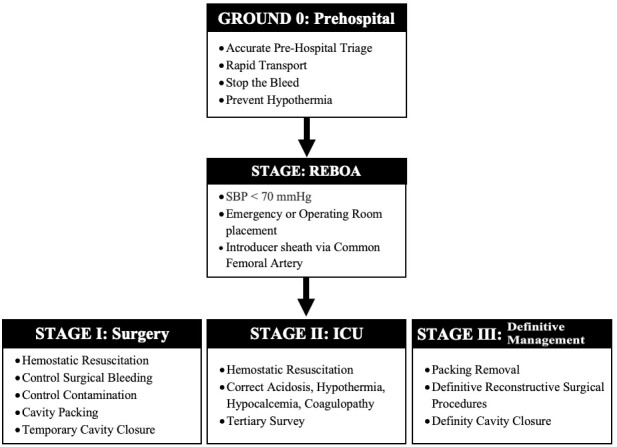

We have just described the classic stages involved in the concept of DCR/DCS, however, thanks to the advances in technology, a bridge has been created between Pre-hospital Management and the Control of Bleeding described before Stage I of DCS which is the inclusion and placement of a REBOA 38 , 39 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Damage Control Surgery: Stages including REBOA.

This endovascular balloon technique is not a recent development, the first reports on this technique dates back to 1954 during the Korean War 40 , 41 . However, the development of a specific balloon catheter for hemorrhage control in trauma scenarios has only occurred recently, being the CTE Cali Group an international pioneer in its clinical implementation and a source of scientific evidence that has contributed to its consolidation in the field of trauma surgery 42 , 43 . Such findings have included the following:

REBOA is not only a tool that aids in the control of hemorrhage, it is also a vital tool in the hemodynamic resuscitation of a severely injured patient allowing for the intra-vascular volumetric content to remain directed towards essential organs which include the brain and the heart 44 , 45

REBOA is a dynamic tool that requires the placement and ongoing management by a skilled and well-trained surgeon 46 - 48

REBOA poses a new paradigm shift in which soon after the initial ABCDE evaluation proposed by ATLS, an introducer sheath should be placed via the common femoral artery in the Trauma Bay / ER, which allows for immediate ongoing real time blood pressure monitoring of the hemodynamically unstable severely injured trauma patient and if indicated (SBP <70 mmHg) the placement of a REBOA with the aim of reducing cell injury and hemodynamic decompensation by early proximal control of the source of bleeding in both blunt and penetrating trauma 42 , 46 , 49 , 50

It is our belief that the classic description of DCR may be leaving out one other crucial arm that may interact positively with the other three. We propose a new paradigm “The Fourth Pillar”: Permissive Hypotension, Hemostatic Resuscitation, Damage Control Surgery and REBOA (Figure 6). To this point, we have extended the indications of REBOA use and have applied it to salvage patients with penetrating and blunt trauma not only of the abdomen and pelvis 40 , 44 but also of the chest which until our reported initial successful experience was considered a contraindication 42 , 46 , 51 - 53 . However, we are not promoting its vast use for all trauma patients but instead its use in specific well indicated dire scenarios of hemodynamic instability from ongoing non-compressible torso hemorrhage and impending cardiac arrest 54 .

Figure 6. REBOA as an integral component of DCR/DCS.

Finally, we are aware that the inclusion of a REBOA program as part of a Trauma Teams’ armamentarium is costly and requires a significant investment that may be out of reach to many centers in Latin America and other parts of the world but we believe that in time this technology will be accessible to all those that may benefit from its use.

Conclusion

The development of the concepts of Damage Control Resuscitation and Damage Control Surgery have been one of the most important advancements in trauma surgery. These concepts have been classically based on three fundamental pillars: permissive hypotension, hemostatic resuscitation and surgical damage control. We have introduced a fourth pillar which is the inclusion of the Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA).

References

- 1.Stone HH, Strom PR, Mullins RJ. Management of the major coagulopathy with onset during laparotomy. Ann Surg. 1983;197:532–535. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198305000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmona RH, Lim RC, Lim RC. The role of packing and planned reoperation in severe hepatic trauma. J Trauma. 1984;24:779–784. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198409000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, Burch JM, Bitondo CG, Jordan GL. Packing for control of hepatic hemorrhage. J Trauma. 1986;26:738–743. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198608000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krige JEJ, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Therapeutic perihepatic packing in complex liver trauma. Br J Surg. 1992;79:43–46. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotondo MF, Zonies DH. The damage control sequence and underlying logic. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:761–777. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70582-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson JW, Gracias VH, Schwab CW, Reilly PM, Kauder DR, Shapiro MB. Evolution in damage control for exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:261–271. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara A, MacArthur JD, Wright HK, Modlin IM, McMillen MA. Hypothermia and acidosis worsen coagulopathy in the patient requiring massive transfusion. Am J Surg. 1990;160:515–518. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)81018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmermans J, Nicol A, Kairinos N, Teijink J, Prins M, Navsaria P. Predicting mortality in damage control surgery for major abdominal trauma. S Afr J Surg. 2010;48:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beecher H. Preparation of battle casualties for Surgery. Ann Surg. 1945;121:769–792. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194506000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannon E. Nature and treatment of wound shock and allied conditions. JAMA. 1918;70:520–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.1918.02600080022008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holcomb JB, Jenkins D, Rhee P, Johannigman J, Mahoney P, Mehta S. Damage control resuscitation Directly addressing the early coagulopathy of trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62:307–310. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180324124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bickell WH, Wall MJ, Pepe PE, Martin RR, Ginger VF, Allen MK. Immediate versus Delayed Fluid Resuscitation for Hypotensive Patients with Penetrating Torso Injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1105–1109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox CJ, Gillespie DL, Cox ED, Kragh JF, Mehta SG, Salinas J. Damage control resuscitation for vascular surgery in a combat support hospital. J Trauma. 2008;65:1–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318176c533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannon JW, Khan MA, Raja AS, Cohen MJ, Como JJ, Cotton BA. Damage control resuscitation in patients with severe traumatic hemorrhage A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:605–617. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, Fox EE, Wade CE, Podbielski JM. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1 1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: The PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:471–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borgman MA, Spinella PC, Perkins JG, Grathwohl KW, Repine T, Beekley AC. The ratio of blood products transfused affects mortality in patients receiving massive transfusions at a combat support hospital. J Trauma. 2007;63:805–813. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181271ba3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sperry JL, Ochoa JB, Gunn SR, Alarcon LH, Minei JP, Cuschieri J. An FFP PRBC transfusion ratio >/=1:1.5 is associated with a lower risk of mortality after massive transfusion. J Trauma. 2008;65:986–993. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181878028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhee P, Koustova E, Alam HB. Searching for the optimal resuscitation method Recommendations for the initial fluid resuscitation of combat casualties. J. Trauma. 2003;54:S52–S62. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000064507.80390.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holcomb JB. Transport time and preoperating room hemostatic interventions are important Improving outcomes after severe truncal injury. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:447–453. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holcomb JB, Jenkins DH. Get ready whole blood is back and it's good for patients. Transfusion. 2018;58:1821–1823. doi: 10.1111/trf.14818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pivalizza EG, Stephens CT, Sridhar S, Gumbert SD, Rossmann S, Bertholf MF, et al. Whole blood for resuscitation in adult civilian trauma in 2017: A narrative review. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:157–162. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giancarelli A, Birrer KL, Alban RF, Hobbs BP, Liu-Deryke X. Hypocalcemia in trauma patients receiving massive transfusion. J Surg Res. 2016;202:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ditzel RM, Anderson JL, Eisenhart WJ, Rankin CJ, DeFeo DR, Oak S. A review of transfusion- And trauma-induced hypocalcemia Is it time to change the lethal triad to the lethal diamond? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88:434–439. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asensio JA, Petrone P, Roldán G, Kuncir E, Ramicone E, Chan L. Has evolution in awareness of guidelines for institution of damage control improved outcome in the management of the posttraumatic open abdomen. Arch Surg. 2004;139:209–214. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arthurs Z, Kjorstad R, Mullenix P, Rush RM, Sebesta J, Beekley A. The use of damage-control principles for penetrating pelvic battlefield trauma. Am J Surg. 2006;191:604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrada R, Birolini D. New concepts in the management of patients with penetrating abdominal wounds. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:1331–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirshberg A, Mattox KL. Top Knife. Springer; 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Digiacomo JC, Rotondo MF, Schwab CW. Transcutaneous balloon catheter tamponade for definitive control of subclavian venous injuries. J Trauma. 1994;37:111–113. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199407000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAnena OJ, Moore EE, Moore FA. Insertion of a retrohepatic vena cava balloon shunt through the saphenofemoral junction. Am J Surg. 1989;158:463–466. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas S V, Dulchavsky SA, Diebel LN. Balloon tamponade for liver injuries Case report. J Trauma. 1993;34:448–449. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199303000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugrue M, Jones F, Janjua KJ, Deane SA, Bristow P, Hillman K. Temporary abdominal closure a prospective evaluation of its effects on renal and respiratory physiology. J Trauma. 1998;45:914–921. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Degiannis E, Levy RD, Velmahos GC, Mokoena T, Daponte A, Saadia R. Gunshot injuries of the liver The Baragwanath experience. Surgery. 1995;117:359–364. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(05)80053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen R, Sarani B. Evaluation and management of intraabdominal hypertension. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2020;26:192–196. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abramson D, Scalea TM, Hitchcock R, Trooskin SZ, Henry SM, Greenspan J. Lactate clearance and survival following injury. J Trauma. 1993;35:584–589. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199310000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maluso P, Olson J, Sarani B. Abdominal Compartment Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirshberg A, Mattox KL. Planned reoperation for severe trauma. Ann Surg. 1995;222:3–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris JA, Eddy VA, Rutherford EJ. The trauma celiotomy The evolving concepts of damage control. Curr Probl Surg. 1996;33:609–700. doi: 10.1016/s0011-3840(96)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butler FK, Holcomb JB, Shackelford S, Barbabella S, Bailey JA, Baker JB. Advanced Resuscitative Care in Tactical Combat Casualty Care TCCC Guidelines Change 18-01:14 October 2018. J Spec Oper Med. 2018;18:37–55. doi: 10.55460/YJB8-ZC0Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biffl WL, Fox CJ, Moore EE. The role of REBOA in the control of exsanguinating torso hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:1054–1058. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hughes CW. Use of an intra-aortic balloon catheter tamponade for controlling intra-abdominal hemorrhage in man. Surgery. 1954;36:65–68. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belenkiy SM, Batchinsky AI, Rasmussen TE, Cancio LC. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control Past, present, and future. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:S236–S242. doi: 10.5555/uri:pii:0039606054902664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ordoñez CA, Manzano-Nunez R, Rodriguez F, Burbano P, García AF, Naranjo MP. Current use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in trauma. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2017;45:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.rca.2017.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brenner ML, Moore LJ, DuBose JJ, Tyson GH, McNutt MK, Albarado RP. A clinical series of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control and resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:506–511. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e31829e5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beyer CA, Hoareau GL, Kashtan HW, Wishy AM, Caples C, Spruce M, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in a swine model of hemorrhagic shock and blunt thoracic injury. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46(6):1357–1366. doi: 10.1007/s00068-019-01185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beyer CA, Johnson MA, Galante JM, DuBose JJ. Zones matter Hemodynamic effects of zone 1 vs zone 3 resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta placement in trauma patients. Injury. 2019;50:855–858. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ordoñez CA, Khan M, Cotton B, Perreira B, Brenner M, Ferrada P, et al. The Colombian Experience in Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA): The Progression from a Large Caliber to a Low-Profile Device at a Level I Trauma Center. Shock. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manzano-Nunez R, Herrera-Escobar JP, DuBose J, Hörer T, Galvagno S, Orlas CP. Could resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta improve survival among severely injured patients with post-intubation hypotension. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44:527–533. doi: 10.1007/s00068-018-0947-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parra MW, Ordoñez CA, Herrera-Escobar JP, Gonzalez-Garcia A, Guben J. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for placenta percreta/previa. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:403–405. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGreevy DT, Abu-Zidan FM, Sadeghi M, Pirouzram A, Toivola A, Skoog P. Feasibility and Clinical Outcome of Reboa in Patients with Impending Traumatic Cardiac Arrest. Shock. 2019;54(2):218–223. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ordoñez CA, Herrera-Escobar JP, Parra MW, Rodriguez-Ossa PA, Puyana JC, Brenner M. A severe traumatic juxtahepatic blunt venous injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:674–676. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.García AF, Manzano-Nunez R, Orlas CP, Ruiz-Yucuma J, Londoño A, Salazar C, et al. Association of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) and mortality in penetrating trauma patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meléndez JJ, Ordóñez CA, Parra M, Orlas CP, Manzano-Núñez R, García AF. Balón de reanimación endovascular de aorta para pacientes en riesgo o en choque hemorrágico experiencia en un centro de trauma de Latinoamérica. Rev Colomb Cir. 2019:124–131. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ordoñez CA, Rodríguez F, Parra M, Herrera JP, Guzmán-Rodríguez M, Orlas C. Resuscitative endovascular balloon of the aorta is feasible in penetrating chest trauma with major hemorrhage Proposal of a new institutional deployment algorithm. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89:311–319. doi: 10.1097/ta.0000000000002773.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bulger EM, Perina DG, Qasim Z, Beldowicz B, Brenner M, Guyette F. Clinical use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in civilian trauma systems in the USA, 2019: a joint statement from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians and the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2019;4:e000376. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2019-000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]