Dear Editor,

COVID-19 has been at the centre of a devastating 21st century pandemic, claiming over 600,000 lives as of August 1st, 2020.1 With a limited supply of vaccines against COVID-19, protective measures remain key for slowing down its spread. Since the start of the pandemic, protective measures have been implemented on a worldwide level. Implementation of such measures necessitates awareness of the public. Raising public awareness requires powerful and impactful messages, displayed on widely viewed communication platforms for rapid dissemination of accurate information.

For many, social media have been the primary sources of information and insight into the COVID-19 pandemic.2 While the landscapes of social media do harbour trustworthy material from reliable sources, rumours or misinformation have often propagated faster and on larger scales.2–4 In these times of crises, rumours running rampant can often escalate anxiety and fear among the public, leading to a state of information overload or cyberchondria, which ultimately results in wrongful and harmful practices.4,5 For instance, claims in March 2020 by the previous President of the United States, Donald Trump, regarding his own personal intake of hydroxychloroquine for prevention of COVID-19 lead to a sharp increase in both hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine prescriptions in the United States.6 Ultimately, this has led to several reports of drug overdose in people that took the drug without medical supervision.4–6

While the world struggles to control the virus, reduction of misinformation and rumours is vital in the management of this pandemic. An impactful way to combat misinformation is through strong and influential presence of medical professionals on social media. Although increasing in prevalence, the collective social media presence of medical professionals has been lacking.7 A recent report concluded that only 43% of healthcare practitioners who own social media accounts would utilise them for educational purposes, with the probability significantly decreasing in those ≥40 years old.8 Additionally, in a survey encompassing more than 4,000 physicians, more than 90% of physicians reported the use of social media for personal activities. However, only 65% reported use of such platforms for professional purposes.9,10 The shortage of sound and influential professional voices on social media has created a significant void that was deepened by the public thirst for knowledge and filled with misconceptions and false information.

It is time for medical professionals to embrace social media’s formidable influence and put it to good use. The traditional methods of spreading public awareness via intermediaries such as television channels, locally organised public events and others have limited reach. They are usually time, cost and space prohibitive at the time of a pandemic. On the other hand, through social media’s digitalised platforms, medical professionals can reach hundreds, if not tens of thousands of people, with just a few clicks and at little to no cost.11

Social media’s value extends beyond combating misinformation to fueling public learning of vital medical concepts during COVID-19. Such concepts include principles in vaccine development, experimental drug treatments and others. Explaining and rationalising complex medical ideas in simple terms can lift the haze of ambiguity. Ambiguity, during times of uncertainty, generates fear, reluctance and ultimately avoidance.

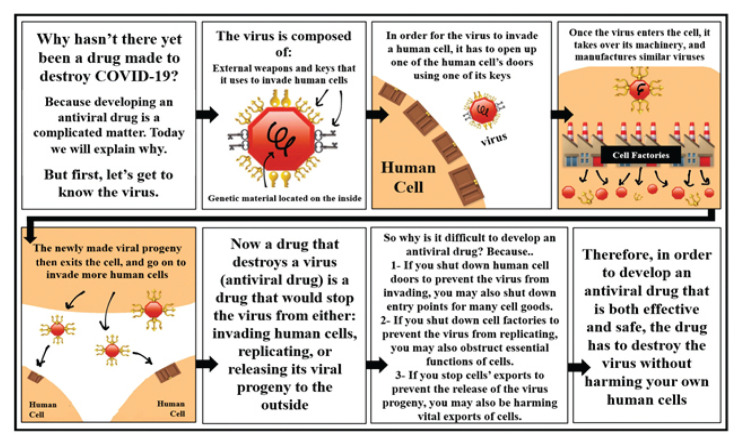

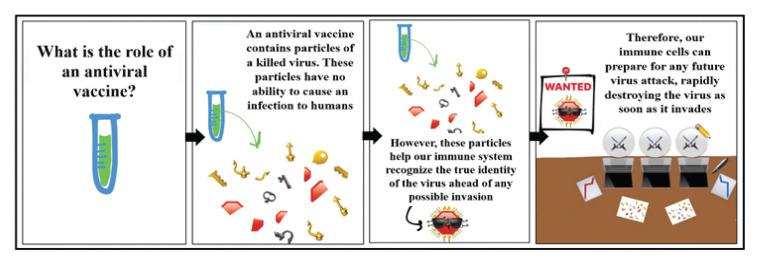

Through a self-developed professional social media presence that hosts over 100,000 users, I have constructed numerous self-made visuals and videos that have illustrated various medical concepts before and during this pandemic.12 Through the simple yet compounded usage of “emojis”, I have developed constructs on principles of antiviral development and vaccinations against viruses [Figures 1 and 2].13,14 These constructs received a broad public appraisal, registering over 135,000 views in one month.13,14 While many physicians have adopted similar professional digital platforms for health education, the utilisation of simplistic yet expressive and elaborative emoji-constructed health demonstrations has not been done before the same extent expressed in this letter by the author. The adaptation of common everyday humanistic activities (i.e. unlocking of doors with keys, invasion of foreign territories) and utilising such activities to illustrate and mirror complex medical principles is both creative and extremely engaging.12 More importantly, these constructions can be done with the simple tools located in any smartphone without any prior knowledge of sophisticated digital design software. The combination of simple language, brief but robust statements, entertaining visuals and drawing resemblances to everyday life have made these simple illustrations incredibly impactful. In this instance, a picture was worth a thousand words.

Figure 1.

Visual illustration, as it appeared on social media on March 13th, 2020, showing the structure of COVID-19, its mechanism of human cell invasion, replication and release from human cells.13

Figure 2.

Visual illustration, as posted on social media on March 19th, 2020, explaining the principles in development of vaccines against viruses.14

It is worth noting here that the latter demonstrations in Figures 1 and 2 were originally posted in Arabic, targeting the Arabic-speaking population and were subsequently adapted and translated for the present paper. From my years of experience building my health education platform, the extent of public education for Arabic speaking nations has been lacking. It often does not meet the public’s demand for updated health information. Additionally, pre-existing methods and tools for education lack the element of simplicity and public engagement. The designs and posts illustrated in this letter and many others have served to bridge the gap in these critical educational healthcare delivery domains.15

Social media is here to stay. Moreover, without a clear direction in the form of robust medical professional presence on social media, public health education, particularly in the Arab world, will suffer. We ought not to fear from engaging in the online world of social media. Instead, we should embrace it and plan to engage in it strategically and thoughtfully. Here, I present a condensed list of recommendations for building an educational social media presence. First, start by creating a public, visible profile on one social media platform. Second, pick medical themes relevant to your speciality or time of posting. Then, explain the themes and concepts in simple terms, preferably drawing examples from everyday life. Seek feedback from viewers and colleagues on areas to improve (visuals, sound effects, selection of topics, or even presentation style). Finally, always be cognizant of your professional presence and maintain the same ethical standards exercised during in-person dealings. It must also be emphasised here that building a widely viewed platform is no easy task; it takes grit, time and resilience. Nevertheless, the impact could be remarkable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019 situation reports. [Accessed: Aug 2020]. From: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports.

- 2.Armitage L, Lawson BK, Whelan ME, Newhouse N. Paying SPECIAL consideration to the digital sharing of information during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. BJGP Open. 2020;4 doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101072. bjgpopen20X101072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llewellyn S. Covid-19: How to be careful with trust and expertise on social media. BMJ. 2020;368:m1160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasnim S, Hossain MM, Mazumder H. Impact of Rumors and Misinformation on COVID-19 in Social Media. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020;53:171–4. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farooq A, Laato S, Islam AKMN. Impact of Online Information on Self-Isolation Intention During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19128. doi: 10.2196/19128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman J, Giles C. Coronavirus and hydroxychloroquine: What do we know? [Accessed: Aug 2020]. From: https://www.bbc.com/news/51980731.

- 7.Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: Benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39:491–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pizzuti AG, Patel KH, McCreary EK, Heil E, Bland CM, Chinaeke E, et al. Healthcare practitioners’ views of social media as an educational resource. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, Patients and Social Media. [Accessed: Feb 2021]. From: www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/doctorspatientsocialmedia.pdf.

- 10.Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: Benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39:491–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lake H, Bermingham F, Johnson G, Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:E2997. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali KF. Instagram. [Accessed: Aug 2020]. From: www.instagram.com/dr.khawla.fuad.ali.

- 13.Ali KF. Instagram. [Accessed: Aug 2020.]. From: www.instagram.com/p/B9q4sZoH8Kw/

- 14.Ali KF. Instagram. [Accessed: Aug 2020.]. From: www.instagram.com/p/B96snfUHvQl/

- 15.Elkhayat H, Amin MT, Thabet AG. Patterns of use of social media in cardiothoracic surgery; surgeons’ prospective. J Egypt Soc CardioThorac Surg. 2018;26:231–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jescts.2018.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]