Abstract

Background:

Although incarcerated women are a highly victimized population, therapy for sexual violence victimization (SVV) sequela is not routinely offered in prison. SHARE is a group therapy for SVV survivors that was successfully implemented and sustained in a women’s correction center. Here, we aimed to identify implementation factors and strategies that led to SHARE’s success and describe incarcerated women’s perspectives on the program.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective process evaluation using interviews structured according to EPIS, a well-established implementation science framework. Participants (N = 22) were incarcerated women, members of the SHARE treatment team, and members of the correction center’s leadership, therapeutic team, and volunteer program.

Results:

Factors that facilitated SHARE implementation varied by EPIS phase and organization. Positive inter-organizational and interpersonal relationships were key across phases, as were the synergies between both the strengths and needs of each organization involved in implementation. Incarcerated women reported a strong need for SHARE and did not report any concerns about receiving trauma therapy in a carceral setting.

Conclusions:

Therapy for SVV sequelae, including exposure-based therapy, is possible to implement and sustain in carceral settings. Community–academic partnerships may be a particularly feasible way to expand access to SVV therapy for incarcerated women.

Keywords: sexual violence, group therapy, incarcerated women, implementation science, PTSD

Over the last 40 years, more expansive law enforcement, stiffer drug sentencing laws, and unique barriers to successful community reentry have caused the number of women who are incarcerated in the U.S. to increase over 750%, or from 26,378 in 1980 to 225,060 in 2017 (Bronson & Carson, 2019). The “war on drugs” had a profound impact on women; even though women are less likely than men to play a central role in the drug trade, they are more likely to serve time for drug-related offenses or property crime (Bronson & Carson, 2019). Policy changes are needed to reverse these national trends; however, interventions that reduce barriers to women’s successful community reentry may improve quality of life and reduce re-incarceration.

As sexual violence victimization (SVV) sequelae (e.g., drug use, mental illness, sex work) are known contributors to incarceration and recidivism (Grella, Stein, & Greenwell, 2005; Scott, Grella, Dennis, & Funk, 2014), they have emerged as clear targets for interventions aiming to improve the outcomes of incarcerated women (Aday, Dye, & Kaiser, 2014; Herbst et al., 2016; Karlsson & Zielinski, 2018). A recent review found that SVV prevalence among incarcerated women is 50%–66% in childhood, 28%–68% in adulthood, and 56%–82% for lifetime (Karlsson & Zielinski, 2018). SVV confers increased risk for psychiatric problems (Dworkin, Menon, Bystrynski, & Allen, 2017); in turn, psychiatric problems increase risk for justice involvement (Lynch et al., 2017). For example, posttraumatic stress symptoms are associated with drug use severity (Back et al., 2000; McCauley, Kileen, Gros, Brady, & Back, 2012) even after drug treatment (Glasner-Edwards, Mooney, Ang, Hillhouse, & Rawson, 2013) and predict post-release relapse and recidivism (Kubiak, 2004). A study of women in prison found that women with an SVV history were also more likely to use drugs and exchange sex for money or drugs (Abrams, Etkind, Burke, & Cram, 2008). Moreover, women are often intoxicated on drugs and/or alcohol at the time of their offense (Greenfeld & Snell, 2000). Collectively, findings indicate links between SVV exposure and women’s involvement in the criminal justice system.

Yet, therapy for addressing psychological sequela (e.g., PTSD, depression, anxiety) of SVV and/or other traumas is not yet part of routine care in carceral settings. Some barriers to therapy in prisons are practical (e.g., spontaneous relocation, segregation; Wolff et al., 2015). There are also fears that trauma-focused therapy implementation in prison risks “emotionally destabilizing [people] who are already vulnerable” (Miller & Najavits, 2012). These challenges highlight the need to better understand how to effectively implement therapy for SVV and other traumas in light of carceral facility characteristics and appropriate consideration for vulnerable persons. The voices of people who are or have been incarcerated are critical to prioritize in such discussions—yet, incarcerated women’s voices on this topic are notably lacking in the literature to date.

Implementation of Survivors Healing from Abuse: Recovery through Exposure (SHARE)

Since 2012, members of our research team have been implementing, supervising, and/or evaluating SHARE (Karlsson, Zielinski, & Bridges, 2019b), a promising, exposure-based group therapy for incarcerated women who are SVV survivors (see Table 1 for an overview). Open-label pilot studies have demonstrated that SHARE is a feasible and acceptable therapy for incarcerated women, with over 250 women completing SHARE to date (Karlsson, Bridges, Bell, & Petretic, 2014; Karlsson, Zielinski, & Bridges, 2015, 2019a). Across pilots, SHARE has also demonstrated large pre-treatment to post-treatment effects on PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Since its inception, SHARE has been continuously offered at one women’s correction center—providing a ripe context for studying factors that have facilitated successful implementation.

Table 1.

SHARE Overview

| Sessions | Components | Therapeutic Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | • Establishing group norms • Psychoeducation about trauma and rationale for imaginal exposure • Coping skills |

• Build rapport • Enhance motivation • Build efficacy |

| 3–7 | • Imaginal exposure (1–2 per session) with supportive feedback from group members and therapists | • Approach (rather than avoid) distressing memories • Break learned fear response/allow natural emotions to occur • Normalize experiences |

| 5–7 | • Discuss/challenge common cognitive themes that emerge in trauma narratives | • Develop more balanced views of the traumatic event and one’s role in it |

| 8 | • Consolidate group experience • Relapse prevention |

• Anticipate lapses • Provide hope for continued healing |

Studies of long-term sustainability of interventions are rare, often ending at the end of a funded research study. SHARE implementation was not grant-funded; rather, it began as a partnership between a women’s correction center, a clinical psychology doctoral program, and a domestic violence shelter. Such university-community partnerships are common avenues through which psychologists foster training opportunities for students and enact community psychology values such as a commitment to collaboration with contexts that can improve health equity. Rigorously studying the implementation and sustainment of SHARE has potential to guide community psychologists who may be pursuing similar collaborations and aligns with the community psychology value of pursuing science in the service of social justice (SCRA, 2020).

SHARE Implementation Setting and Partners

Women’s Community Correction Center.

Northwest Arkansas Community Correction Center (NWACCC) is the 120-bed minimum-security women’s prison where SHARE has been offered since January 2012. Most residents are non-Latina White (~97%), incarcerated on drug and/or financial felony charges, and serving sentences of 3 years or less. Residents are typically eligible for parole after serving one third of their sentence. Leadership consists of a Center Supervisor (akin to a Warden) and Assistant Center Supervisor, who oversee the treatment and security staff. Treatment staff offer daily group programming, monthly individual counseling sessions, and reentry planning services. NWACCC also has a robust volunteer program through which community members facilitate recovery groups (e.g., AA), recreational activities, GED and college courses, job skill classes, and religious services. The Chaplain oversees the volunteer program, including the training, approval (with background checks), and schedule. NWACCC residents who self-identify as having problems due to SVV are eligible to enroll in SHARE.

Clinical Psychology Doctoral Program.

The clinical psychology doctoral program at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville (UAF) has staffed student therapists to facilitate SHARE at NWACCC since 2012. UAF follows the scientist–practitioner model of training. Students are admitted in small cohorts, typically ranging from 4 to 6 students, and graduate with PhD degrees in an average of 5–7 years. Faculty are licensed psychologists and supervise most student clinical work. SHARE has had the same clinical supervisor, who is UAF faculty, since its inception.

Domestic Violence Shelter.

Peace at Home Family Shelter (PAH) is a nonprofit agency that provides emergency shelter, housing assistance, financial assistance, resource access, legal aid, and counseling to victims of domestic violence. PAH employs advocates and case managers, some of whom have specialized legal expertise, and views its mission as including residential services, outpatient services, and community outreach. Each year since 2011, the staff at PAH has included a UAF doctoral student therapist assigned to complete a 20-hour weekly, 9-month practicum. A social worker from PAH shelter linked UAF’s clinical psychology program and NWACCC, and initially co-led SHARE groups with the first UAF student therapist.

Collaboration between NWACCC, UAF, and PAH.

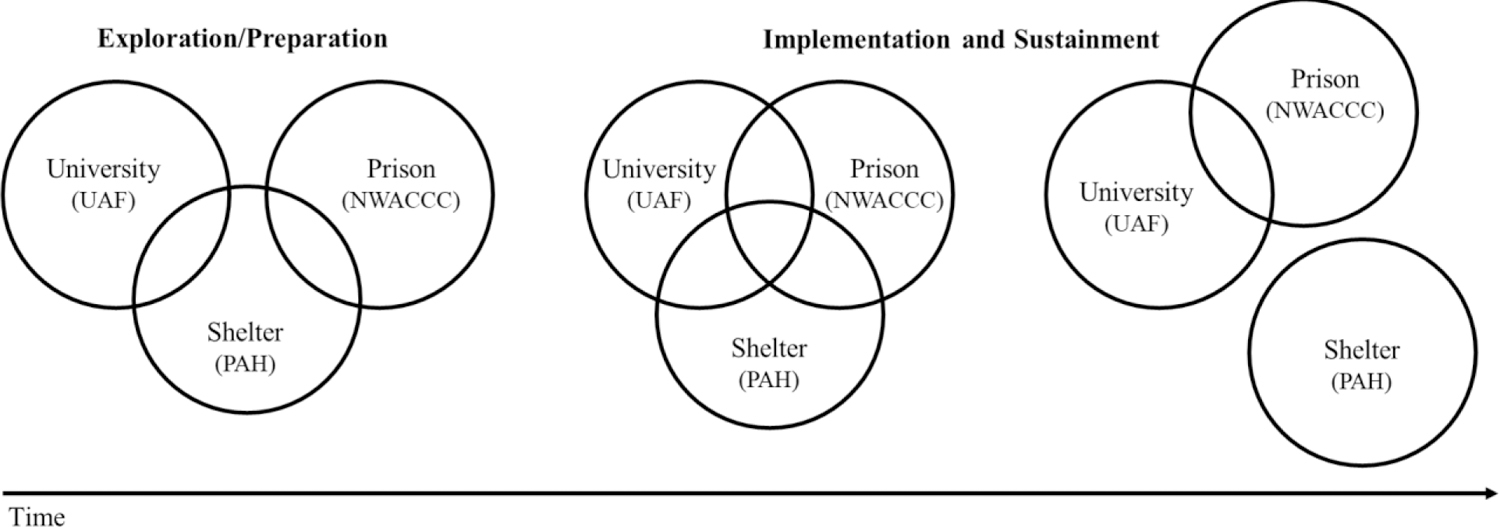

Prior to SHARE implementation, PAH shelter had provided domestic violence education for NWACCC residents. PAH shelter was also a practicum site for UAF’s clinical psychology program, which provided a student therapist each year. NWACCC and UAF’s clinical psychology program did not collaborate prior to this time (see Figure 1, Exploration/Preparation Phase).

Figure 1.

Partnering Agency Roles in SHARE Implementation by EPIS Phase

The three organizations began their collaboration following a community coalition meeting in which staff from NWACCC and PAH shelter discussed the need for NWACCC residents to have access to therapy to address consequences of interpersonal violence. The PAH shelter social worker then approached the UAF student therapist who was placed at PAH shelter about her willingness to lead therapy groups through the volunteer program at NWACCC as part of her practicum. The UAF student therapist agreed. After consulting existing research on interpersonal violence exposure among incarcerated women and learning of the high prevalence of SVV, the UAF student therapist co-created SHARE with her UAF faculty supervisor. Viewing SVV as relevant to the mission of PAH shelter, the PAH social worker co-led SHARE at NWACCC with the UAF student therapist for the first two SHARE groups. During this time, the SHARE treatment team’s UAF members and NWACCC staff members solidified a relationship that would continue after the PAH social worker’s departure (see Figure 1, Implementation and Sustainment phases). To date, more than 40 SHARE groups have been completed at NWACCC. Here, we investigated factors that have contributed to this success.

The Current Study

We conducted a retrospective process evaluation to identify influences on the successful implementation and sustainment of SHARE (i.e., barriers and facilitators). We structured and analyzed our stakeholder interview guide according to an established implementation framework (Aarons, Hurlburt, & Mc Cue Horwitz, 2011; Moullin, Dickson, Stadnick, Rabin, & Aarons, 2019) and aligned our results with this framework and with an existing taxonomy of implementation strategies (Powell et al., 2015). Our primary research questions were:

What factors influenced implementation and sustainment of SHARE?

What strategies were used to support SHARE implementation and sustainment?

We also preliminarily examined the following questions through interviews with residents:

What were residents’ perspectives on SHARE’s fit with the setting and their needs?

What factors influenced (non)participation in SHARE?

Together, this study builds foundational knowledge on how psychologists can successfully partner with carceral systems to address the needs of incarcerated SVV survivors.

Method

Participants and Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. After consent was obtained, participants (N = 22) completed individual semi-structured interviews, which were recorded for later transcription and analysis.

Stakeholder Interviews

Sampling.

Stakeholders were purposively interviewed based on their role in SHARE implementation or at NWACCC. Interviewees were members of the SHARE treatment team (n = 6; UAF student therapists, UAF faculty supervisor, and PAH social worker), members of NWACCC leadership (n = 5; Center Supervisors, Treatment Supervisors, Chaplain), and other NWACCC volunteers (n = 2; addiction recovery group leaders). All stakeholder interviews were completed over the phone and ranged from 20 to 90 minutes (M = 50 minutes).

Interview Guides.

The primary stakeholder interview guide1 was organized by the phases of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment framework (EPIS; Aarons et al., 2011; Moullin et al., 2019).2 Questions aligned with the Exploration/Preparation phase focused on how stakeholders considered the needs NWACCC residents, selected SHARE as a therapy that would address those needs, considered potential implementation influences, and developed an implementation plan. Questions aligned with the Implementation phase asked stakeholders to speak about SHARE initiation and how implementation strategies were adjusted and/or refined. Finally, questions aligned with the Sustainment phase sought to elicit factors that had supported SHARE’s ongoing implementation over time.

Across phases, EPIS posits that the process and success of implementation is determined by 1) the layered contexts in which implementation happens (including Inner Setting and Outer Setting factors, and Bridging Factors that link the two), 2) the characteristics of the people implementing and receiving the intervention, and 3) the characteristics of the intervention itself (Innovation Factors, such as intervention characteristics and fit with the setting). Key Inner Setting factors involve organizational characteristics (e.g., culture and climate, leadership) and individual characteristics (e.g., staff attitudes towards the intervention). Key Outer Setting factors reflect the broader sociopolitical climate and might include funding, networking between organizations, and client characteristics. Therefore, across EPIS phases, we asked about: 1) EPIS constructs as factors at the Inner and Outer Settings affecting SHARE implementation and 2) implementation strategies employed. We anticipated that Bridging Factors would emerge, but did not directly prompt for their occurrence.

Resident Interviews

Sampling.

NWACCC residents were selected for interviews based on three predefined strata (n = 3 for each group): 1) residents who completed SHARE, 2) residents who were interested in SHARE but had not enrolled, and 3) residents who were not interested and had not enrolled. All residents were selected randomly from a larger pool that completed screening measures during a facility meeting. Each resident consented to participate, and interviews occurred in-person in a private office. Residents were incarcerated for a mean of 8.67 months (median = 7 months; range = 4–20 months). Interviews lasted from 20 to 46 minutes (M = 29 minutes). Residents were compensated $10 via account deposit for their time spent participating.

Interview Guide.

NWACCC residents answered questions from a third interview guide, which focused on identifying the factors that influenced their decisions about whether or not to participate in SHARE, including prompts for Inner and Outer Setting factors that might affect their choices. They were also asked about their general perception of SHARE.

Qualitative Analysis

All interviews were transcribed, checked for quality, and analyzed using MAXQDA qualitative software. For stakeholder interviews, we first reviewed each transcript and assigned EPIS phases (Exploration/Preparation, Implementation, or Sustainment) to segments of data. Segments in which stakeholders discussed implementation influences were coded by EPIS domain for each of the three partnering organizations (i.e., factors related to the Inner Setting and Outer Setting of NWACCC, UAF’s clinical psychology program, and PAH shelter), and coded as either facilitators or barriers. Innovation Factors relevant to SHARE implementation were also coded across phases. Finally, the implementation strategies that were discussed were coded, with terms that mapped on to strategies included in the ERIC study (Powell et al., 2015) used when appropriate. We then re-reviewed all contextual segments and inductively coded factors related to the EPIS constructs with descriptive summaries and sub-codes.

Separately, we deductively coded resident interviews. The codebook for resident interviews was created using the interview guide and an iterative process of discussion and refinement. Emergent themes were recorded during analysis.

Results

Factors that Influenced Implementation of SHARE

A summary of the factors that influenced SHARE implementation are displayed in Tables 2 and 3; here, we elaborate upon the identified factors and provide illustrative quotes.

Table 2.

Inner Setting Factors Influencing Implementation of SHARE, by EPIS Phase and Setting

| Setting | Summary Factor | Contributing Codes | E/P | I | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Partners recognized that incarcerated women need therapy for SVV sequelae. | 1. Recognition of need for SVV therapy | + | + | + |

| All | Partners had compatible availability. | 1. Evening availability | + | + | + |

| All | Partners were linked to other agencies. | N/A – fully described by summary factor | + | + | |

| NWACCC and UAF | Email communication is common. | N/A – fully described by summary factor | + | + | +/− |

| NWACCC | Many residents have SVV exposure. | N/A – fully described by summary factor | + | + | + |

| NWACCC | Facility is rehabilitation-focused, but internal treatment staff lacks expertise needed to provide therapy for SVV themselves. | 1. Rehabilitation focused 3. Counselors lack expertise in trauma-focused therapy 4. Counselor limitations |

+ | + | + |

| NWACCC | Relies on volunteers for programming and has been very successful in formalizing operations to support a robust volunteer program. | 1. Relies on volunteers for programming 2. Treatment Supervisor championed implementation of SHARE 3. Had a process for onboarding volunteers 4. Had a system for scheduling and resident selection/enrollment 5. Had a process for approving materials 6. Able to designate physical space for programs |

+ | + | + |

| NWACCC | Leadership support for SHARE was strong. | 1. Supportive leadership 2. Stable leadership 3. Center supervisor was female and had a mental health background* 4. Willing to make changes to support SHARE |

+ | + | + |

| NWACCC | Although rehabilitation-focused, NWACCC is still a prison and shares characteristics with more traditional prisons. | 1. Prisons have rules 2. Security is a competing priority for staff 3. Culture emphasizes accountability 4. Coercive environment 5. Residents have limited privacy 6. Need for staff sensitivity but no training 7. Resident population is fluid** 8. Unpredictable room conditions |

− | − | − |

| NWACCC | Prisons are residential settings that have distinct advantages for recruitment/enrollment. | 1. Residential setting (parent code) a. Can identify residents who need SHARE b. Strong peer-to-peer networks c. Staff able to see that SHARE helps. 2. Facility-wide meetings held twice per day |

+ | + | + |

| NWACCC | Competing programming exists, both internally- and externally-facilitated. | 1. Competing programming exists 2. Competing programs offered in nearby rooms may be loud and/or disruptive 3. Residents have competing priorities |

− | − | − |

| UAF | Presence of a student champion with strong interpersonal skills. | 1. Student champion 2. Willingness to do tasks outside group time 3. Strong interpersonal skills and professionalism |

+ | + | +/− |

| UAF | Presence of a faculty supervisor whose skills and approach were well-matched to SHARE implementation. | 1. Faculty champion 2. Weekly supervision available a. Willingness to supervise community sites b. Had provided therapy in prison before 2. Openness to pilot innovative programming 3. Ability to align SHARE with job expectations a. Valued research/program evaluation b. Obtained research grant |

+ | + | + |

| UAF | Continuous availability of professional and engaging clinically-trained students to lead SHARE. | 1. Students need clinical hours/experiences 2. UAF often admits students with interests relevant to SHARE 2. Students enjoy leading SHARE 3. Peer networks help with recruiting new leaders 3. Long training duration allows students to commit to long-term practicum sites 4. Research skills, interests, and needs |

+ | + | + |

| UAF | UAF is a relatively resource-rich, research- intensive academic environment. | 1. University had funding/resources 2. Faculty have autonomy in community outreach |

+ | + | + |

| PAH | Organization views outreach as part of its mission. | 1. Staff facilitated domestic violence information groups at NWACCC 2. Staff member co-led SHARE 3. SHARE hours were allowed to count toward required PAH practicum hours |

+ | + | +/o |

| PAH | Staff had experience working with interpersonal violence survivors but not providing psychotherapy for SVV. | 1. Staff not prepared to provide trauma-focused therapy, including therapy for SVV sequelae | + |

Phase Notes. EPIS: E/P = Exploration/Preparation, I = Implementation, S = Sustainment

Other Notes.

indicates factor is a facilitator;

indicates factor is a barrier;

indicates factor is both facilitator and barrier;

indicates that a factor was a facilitator in early sustainment but was absent in later sustainment;

SHARE = Survivors Healing from Abuse: Recovery through Exposure

True through early sustainment. Center supervisor in later sustainment did not have a mental health background and was male.

This individual factor is both +/− as population shifts influence SHARE enrollment both positively and negatively.

Table 3.

Outer Setting Factors Influencing Implementation of SHARE, by EPIS Phase and Setting.

| Setting | Summary Factor | E/P | I | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Sexual violence is common. | + | + | + |

| All | Northwest Arkansas is a climate in which there are willing and able volunteers. | + | + | + |

| NWACCC and PAH | Involved in community coalition for agencies serving victims of domestic violence. | + | ||

| NWACCC and UAF | Has existing research approvals process. | + | + | + |

| NWACCC | Accreditation standards as licensed substance use treatment facilities mandate 20 hours of weekly programming facilitated by staff (volunteer groups do not count). | − | − | − |

| NWACCC | Policy changes are shortening sentence lengths and reinforcing practical support over therapeutic programs more similar to SHARE. | − | ||

| UAF | Academic environment has access to research literature, reinforces publishing and grant writing, and provides venues in which to disseminate new knowledge. | + | + | |

| UAF | Clinical psychology trainees are reinforced for unique clinical experiences and for clinical training hours when applying to internships. | + | + | + |

Phase Notes. EPIS: E/P = Exploration/Preparation, I = Implementation, S = Sustainment

Other Notes.

indicates factor is a facilitator;

indicates factor is a barrier;

indicates factor is both facilitator and barrier;

indicates that a factor was a facilitator in early sustainment but was absent in later sustainment;

SHARE = Survivors Healing from Abuse: Recovery through Exposure

Factors that were Shared by Multiple Implementation Partners

Several SHARE facilitators were mentioned during stakeholder interviews across partners (i.e., NWACCC, UAF’s clinical psychology program, PAH shelter). For example, all partners recognized residents’ need for SHARE. One stakeholder stated, “there was recognition across the board [of SHARE’s] relevance to the residents and…how these experiences influence[d] and in a lot of cases landed them [at NWACCC] because [SVV] was connected to their arrest…to drug use or money problems or whatever.” Positive relationships were also described as critical. One stakeholder summarized this well: “The connections…That’s what did it…there were lots of ups and downs for a while, so…a good working relationship was very important.”

Several Outer Setting facilitators also emerged. The fact that SVV is common in the U.S., particularly among incarcerated women, was influential across all phases of EPIS; it resulted in a consistent need for SHARE among NWACCC’s population. The broader social climate in which all partners are nested was also influential. One NWACCC staff member said, “We’ve never had any issues with volunteers wanting to come in…I think our first year we were open, we had 200 [volunteers], and now we’re almost at 400…the environment here is very caring.” A community domestic violence coalition was also crucial during the Exploration/Preparation phase. Without this meeting, which provided NWACCC and PAH shelter an opportunity to discuss collaborations, SHARE would not have been created or implemented.

NWACCC-Specific Factors that Influenced SHARE Implementation

Nearly all of the NWACCC influences on SHARE implementation (Table 2) were consistent across EPIS phases, which created a stable implementation climate. Stakeholders highlighted NWACCC’s focus on rehabilitation as a facilitator. One SHARE treatment team member said, “It’s an amazing facility…it’s very, very rehabilitation focused and that’s evident in all the ways they talk about the residents and the ways that they worked with us.” However, competing programs—including those offered by other volunteers, 20 hours per week of group programming facilitated by staff, and resident job obligations—were often identified as barriers. SHARE student therapists’ evening availability was crucial, as it was the only time that voluntary programs were held at NWACCC. Former student therapists noted that competing programs still occasionally created suboptimal conditions for SHARE. One said, “There were times we were doing an exposure and people [were] really sad and emotional, and we had the church group next door singing…in a very joyful kind of way. And sometimes it was distracting.”

Several barriers stemmed from the fact that, despite being rehabilitation focused, NWACCC is still a prison. Sporadic population counts, limited privacy, and periodic individual and facility-wide disciplinary sanctions all affected SHARE. One SHARE therapist described, “There was a period of weeks that…[residents] were all on code of silence [a sanction that prohibited most conversation]…we wondered [if it was] going to impact treatment, because they can’t use each other for support during that time.” Thus, it was crucial that NWACCC leadership was willing to problem-solve and often even make accommodations to typical rules to facilitate SHARE. One SHARE treatment team member explained, “they facilitated things tremendously…they gave us a lot of flexibility for creating a particular therapeutic kind of milieu in our group.” This flexibility was likely due to strong NWACCC leadership support for SHARE. Stakeholders also noted that NWACCC’s residential nature was a facilitator. For example, one SHARE therapist explained that many residents “join through word of mouth…it’s something different coming from the women themselves, who’ve previously been in the group, than it is coming from us as leaders.” Daily all-facility meetings also gave SHARE therapists a time to introduce themselves and the group to nearly all residents at once.

The NWACCC Treatment Supervisors involved in SHARE implementation served as internal champions throughout all EPIS phases—they guided the SHARE treatment team through approvals, collaboratively problem-solved challenges, encouraged residents to enroll, and facilitated access for evaluation research. One SHARE treatment team member described the NWACCC Treatment Supervisor involved for nearly all of SHARE as “our beacon in the night.” Implementation was also facilitated by NWACCC’s reliance on volunteers, such as the student therapists, due to funding limitations and internal staff’s limited training in therapy and SVV. A stakeholder explained that most treatment staff at NWACCC are not clinically trained, and some do not have even bachelor’s-level education in a human services field like social work or psychology. One NWACCC staff member described, “if we had funding for trainings and things like that…we wouldn’t have needed…volunteers to come in and provide [SHARE].”

During the Sustainment phase, policy changes led to quicker release eligibility for NWACCC residents; however, SHARE implementation was minimally affected because it is a brief therapy. Yet, one NWACCC staff member noted that pressures for carceral settings to prioritize programs seen as more core to basic reentry needs could be a barrier to SHARE in the future: “I audit facilities around the country…some of them just focus on reentry and job applications and that kind of thing. And sadly, it’s moving more and more in that direction, where you’re just dealing with…housing and food and clothing and driver’s license and social security cards rather than dealing with some of the more underlying issues that led to them coming to prison.”

University-Specific Factors that Influenced SHARE Implementation

The influences on SHARE implementation stemming from the Inner Setting of UAF’s clinical psychology program were more varied across EPIS phases. Early on, having a student therapist with strong interpersonal skills and a faculty supervisor whose expertise and approach matched SHARE implementation needs was critical. The first student therapist was described by NWACCC staff as key to forming the relationship between UAF’s clinical psychology program and NWACCC. One NWACCC staff member said, “I was very impressed with [student therapist]…I just knew off the bat that she would be a good part of our program…that she would fit in very well.” From the faculty supervisor’s perspective, having a highly competent student to champion SHARE limited the burden of starting a new practicum site: “her being the communication figurehead with those interpersonal skill sets was critical…In other settings where I developed community partnerships, I have been the one who is much more involved.”

Interviews with SHARE student therapists also noted the ongoing commitment of the faculty supervisor as a critical facilitator across all EPIS phases. In the Exploration/Preparation and Implementation phases, her prior experience doing therapy in a prison and openness to pilot SHARE facilitated rapid implementation. Her ability to align her role in SHARE with several of her job demands—especially research expectations—helped her to sustain her commitment to an unpaid external practicum. She explained, “We get to help the women, we get to train students, and I get to do research and publish. It’s meeting multiple demands…that’s critical because otherwise it’s easy to say ‘let’s take [SHARE] off your plate’.”

Sustainment was also facilitated by the continuous availability of students to lead SHARE and the resources available in the research-intensive academic environment in which UAF’s clinical psychology program resides. Students’ need for unique clinical and research experiences, the long duration of doctoral training, and the alignment between SHARE’s foci and students’ professional goals were all facilitators that led to a steady stream of students willing to co-lead SHARE. For example, one student therapist said, “[I had] a specialized interest with working with women that don’t have access to high quality services…the fit for me was perfect.” Student therapists also reported recruiting one another to the SHARE treatment team, another likely implementation facilitator.

In the Sustainment phase NWACCC staff reported that there was not a clear UAF student champion leading implementation; this was missed and feeling less connected to the SHARE treatment team was described as something that could become a barrier to sustainment in the future. However, NWACCC staff reported that the student therapists remained a good fit for the residents, who “really connected with the [student therapists]. They have this thing with trusting…and being genuine and sincere [and the student therapists] really are—[the residents] express that a lot of the time.” The student therapists’ dependability was also highlighted by an NWACCC staff member, who said, “we need [volunteers] to be here consistently and not have absenteeism…I can’t even recall [the student therapists] not being here unless it was inclement weather.” The resources available within UAF’s clinical psychology program were seemingly critical to this consistency. For example, when selecting student therapists’ practicum sites, funding stability allows faculty to prioritize positive training experiences. UAF’s clinical psychology program is also able to pay for SHARE’s operational expenses (e.g., printing costs). This facilitator was mentioned by multiple NWACCC staff members. One staff member noted that the SHARE treatment team “didn’t charge for their services. If they had, that would have been a barrier.” Another said, “we didn’t have to provide any of the staff for [SHARE]…We didn’t have expertise that was being offered so someone had to pay for that, but it wasn’t us.”

The broader academic context in which UAF’s clinical psychology program exists had a more primary role in the Sustainment phase. Academics have made products like articles and web-based trainings that can be leveraged to train student therapists with a lesser burden on faculty supervisors. Additionally, all stakeholders from UAF’s clinical psychology program mentioned consequences of being on the SHARE treatment team that are reinforced by the priorities/requirements of academia (e.g., clinical hours are required for student therapists, publishing is linked to advancement opportunities for faculty).

Shelter-Specific Factors that Influenced SHARE Implementation

Inner Setting factors that are specific to PAH shelter were mostly mentioned as relevant to the Exploration/Preparation and Implementation phases, which aligned with our knowledge that the PAH social worker co-led only the first two SHARE groups. Facilitators that arose were: 1) PAH viewed NWACCC outreach as included within its mission and 2) PAH staff had experience working with SVV survivors and providing education related to SVV and other forms of interpersonal violence, but not with providing trauma-focused therapy. The PAH social worker summarized these facilitators well, saying, “I used to run…domestic violence informational groups [at NWACCC]…I’d bring handouts and we’d kind of have a topic, but then it was a support group style…I loved working with [NWACCC] and…wish[ed] we could be even more involved.” No Outer Setting factors unique to PAH arose during our interviews.

Innovation Factors that Influenced SHARE Implementation

SHARE was developed specifically for implementation within NWACCC; unsurprisingly innovation factors—and particularly the fit with the NWACCC setting and residents—were identified as contributing to success during the Implementation and Sustainment phases. SHARE’s brief duration made it accessible to residents with relatively short sentences. One SHARE treatment team member highlighted “we needed to be brief because we wanted to make sure [residents] have the opportunity to complete a course of treatment…” The small group format was also described as therapeutic. One NWACCC staff member explained that the “…small group was a help. It gave the [residents a] chance to feel…some security with opening up and…[see that others] share similar problems and help them realize they weren’t alone…”

SHARE’s general structure—including that the group was closed and that expectations about confidentiality and exposure were discussed upfront—were described as a facilitator. However, at times it was reportedly challenging to accomplish the goals of the group within the 1.5 hour session length. One student therapist said “running two exposures during [a] one-and-a-half-hour group, is difficult. A lot of the times that that happens we’ll end up getting out late…” Because the NWACCC building schedule precluded longer sessions, this challenge continued.

Multiple stakeholders mentioned SHARE’s adaptability and fit as key to its success. Its protocol allows each group to decide their own norms and rules, including what is considered a confidentiality violation and how each group session ends. The protocol also prohibits the use of “tools” (i.e., actions that residents can normally take to reinforce or punish other residents’ behavior in NWACCC’s modified therapeutic community structure). Towards the end of SHARE, women are asked about special topics that they would like more information on and there is time devoted to addressing these topics in group and/or resources provided to residents for self-study. However, the innovation factor mentioned as a facilitator by the most people interviewed was that SHARE is a voluntary group. This factor, coupled with SHARE’s consistent presence in NWACCC over time was described as a facilitator. For example, one NWACCC staff member said, “…the [residents] weren’t forced to go and I just think [that] the consistency of…[SHARE] creates a trusting environment…where [residents] are willing to show up and open up.” Notably, SHARE’s exposure-based approach was compatible with NWACCC leadership’s beliefs about effective programming. One Center Supervisor described this compatibility using a metaphor: “In Israel, there’s two seas, [the] Dead Sea and [the] Sea of Galilee…the difference is [that] the sea of Galilee has an outlet, so even though the bad stuff gets in, there’s a place for it to leave. …Most of the ladies coming here are like the Dead Sea. They have all this bad stuff come into their life, but they never had a way for any of it to get out…So [NWACCC’s] whole program [is] centered around getting them to turn everything, deal with it…Can’t none of us change our past, but we can all deal with it. And most of them have turned to drugs, and alcohol…so, we give them another way. And [SHARE] is just another way to prevent- deal with issues that otherwise they wouldn’t.”

SHARE Implementation Strategies

Many strategies were used to enhance the implementation of SHARE; most were among the strategies defined in the ERIC study (Powell et al., 2015) and have been highlighted here in bold for clear identification. The SHARE treatment team identified and prepared champions and local opinion leaders within NWACCC during the Exploration/Preparation and Implementation phases. In the early days, the SHARE treatment team and NWACCC stakeholders held educational meetings in which they also assessed for readiness and identified facilitators and barriers to SHARE implementation. Meetings also provided an opportunity to purposefully reexamine and tailor strategies throughout the Implementation and Sustainment phases. For example, one SHARE therapist said “ [we] started [giving] certificates of completion. That wasn’t something we planned on the front end, but it turned out to be super important.”

The academic partnership between UAF’s clinical psychology program and NWACCC combined individual expertise that facilitated SHARE development and research. The UAF faculty supervisor also met annually with NWACCC leadership throughout the Sustainment phase and provided clinical supervision across all phases—a critical strategy because student therapists require this to practice. Because NWACCC staff desired close communication with the SHARE treatment team, ongoing communication with internal champions was also critical. SHARE student therapists sent emails with updates, questions, and concerns to NWACCC’s Treatment Supervisor, who was an implementation facilitator, weekly. One SHARE treatment team member said, “She had to help us set up a system for how to recruit and how to enroll them in the group, and how to notify who was going to be in the group. But also how to deal with any potential issues that would show up in relation to the group.” The SHARE treatment team also developed tools for fidelity and quality monitoring and obtained feedback from residents during the Implementation phase. This feedback was used to adjust SHARE materials and implementation strategies. One SHARE therapist said, “A lot of it was asking [the residents] for feedback. Every time we would run the group, we would ask them at the end, ‘What was it like for you to sign up for this group?’ or, ‘What were your thoughts about it?’….We would just learn from what they were telling us.” Residents also became involved in recruitment, offering to share their stories with peers: “women wrote about their experience in the SHARE group…we read those at the recruitment meetings.”

The SHARE treatment team was structured according to a vertical training model, which created a sustainable model for onboarding SHARE student therapists. One student therapist explained that training was mostly “through observation…and we have a SHARE Dropbox folder, where we have [webinar links], relevant articles about exposure, and materials related to group…and then through peer-supervision…” Each SHARE group is co-led by two student therapists: a junior student first observing the senior student, then leading group themselves with the guidance of the senior student. The development of these clinical implementation teams has contributed to sustainability even though some key stakeholders have left their original positions and/or are no longer directly involved.

Organizational Shifts over Implementation

SHARE provided an opportunity for NWACCC and UAF’s clinical psychology program to form a relationship that was initially facilitated by, but grew increasingly independent of PAH shelter. As one NWACCC leader explained, “Certainly the staff grew to respect [the SHARE student therapists] and they became part of the team.” Ultimately, this made it possible for SHARE to continue despite the decreasing role of PAH shelter in SHARE implementation over time (the PAH social worker who initially co-led SHARE left PAH after two groups and student therapists for UAF’s clinical psychology program who were not placed at PAH shelter were eventually allowed to join the SHARE treatment team; Figure 1).

Resident Perspectives on SHARE

Residents gave their perspective on SHARE and on factors that influenced their decisions about whether or not to enroll. Perhaps most strikingly, all residents—regardless of whether or not they completed the SHARE program—felt that correctional centers should offer therapy for SVV. One resident said, “those memories and the trauma and the feelings, and opening those old scars back up is painful. It hurts. A lot of the reason why we did a lot of the things we did out there is because it hurt and we were just trying to avoid everything to do with it. So, I think it’s great to do it in here. It’s a safe place. We can’t hurt ourselves or anybody else… I couldn’t think of a better place.” Another resident said that she had time for self-improvement because she was incarcerated; for her, there were fewer competing obligations and the cost of treatment was not a barrier. She, in part, said, “I’m very grateful for [SHARE]. Because I know that’s not something I’d go get treatment for on the outside, and treatment like that costs a lot of money too, you know? So…I’m very happy that I was referred to [SHARE] and was able to go to it.”

When asked about factors they considered when deciding whether to participate in SHARE, residents often mentioned being scared to trust others and worries about confidentiality. Some residents perceived strong emotions (e.g., shame, general social anxieties) and discomfort talking about SVV experiences as reasons that some women never enroll in SHARE. No residents expressed concerns specific to the NWACCC environment or to being incarcerated, despite being explicitly asked. Across all participant strata, residents frequently cited a desire for self-improvement as a primary factor when choosing among competing programs. Notably, competing programming and its perceived relevance to one’s own goals was described as a primary influence on participation in various groups. Residents perceived that people who enrolled in SHARE likely wanted to “get [their experiences] off their chest.”

Residents who had completed SHARE noted that they chose to participate because they were driven to improve their lives. They also reported that sharing their story of SVV was helpful. For example, one resident said, “Now I feel great. I feel like I can talk about it, and I can share my testimony…it gives me hope and I don’t feel like I’m damaged anymore.” Another resident said, “I liked the fact that I could deal with it and get it off my chest…I think keeping it in just makes the problems worse.” Residents also noted that staff were influential in raising awareness about SHARE and helping them see its applicability. One woman stated, “I didn’t think I needed [SHARE]. I thought I was okay…and I really think it helped a lot.” When asked about incentives for SHARE participation, many residents noted the importance of receiving a certificate of completion. One resident explained, “I like my certificate, because it shows that I completed something…And I don’t really [complete] a lot of things in life, so to be able to [complete SHARE], I feel like I took care of it. I have a piece of paper to show that I took care of it.”

Discussion

Incarcerated women have tremendous need for therapy that, like SHARE, empowers them to acknowledge and heal from SVV. The sustainment of SHARE at NWACCC demonstrates that psychologists and their trainees can help to fill this crucial service gap through collaboration with community and carceral settings in a manner that provides a benefit to all involved. Resident interviews revealed that incarcerated women believe that it is imperative to offer therapy for SVV in carceral settings, and provided insight in to factors that influence their decisions about whether to enroll in such programs. These insights will assist community providers as they collaboratively implement promising new practices, such as SHARE, in carceral settings with the goal of improving health equity among people who are underserved.

Our evaluation highlights that factors specific to the organization(s) from which community psychologists come, the partnering carceral agency, and their overlap heavily influence implementation efforts. Summarizing across these factors, it seems that SHARE implementation was successful in large part because each implementation partner brought something needed—but not already available within the other organization(s)—to the partnership and shared a mutual goal of improving incarcerated women’s access to therapy to address the consequences of SVV. The degree to which values, visions, and priorities are similar between organizations has recently been termed “inter-organizational alignment” (Lyon et al., 2018). Here, we found that differing but complementary organizational priorities can lead to sustainment of interventions that, like SHARE, are needed by the population all agencies strive to serve. Notably, this was the case even with limited financial resources and without financial compensation for services rendered. Relationships and interpersonal characteristics were also crucial to SHARE implementation—especially in the early stages. Implementation facilitation, a relationally-grounded strategy often involving internal and external champions, may be well-matched to carceral settings. Bridging factors (e.g., volunteer programs, contracts) may too prove critical.

It is also worth noting that the extraordinarily high SVV prevalence among incarcerated women facilitated SHARE because it resulted in a constant stream of women who need and are referred to treatment. This large potential SHARE recipient base points to the need for SVV prevention programs and societal safety nets that keeps women out of incarceration. Although intervention sustainability is commonly discussed as desirable, true success may occur when SHARE is no longer sustainable because it is no longer needed. Until this happens, our results incrementally build upon the nascent knowledge of strategies that community psychologists use to sustainably support programs like SHARE in carceral settings (see Table 4 for summary considerations). Additional rigorously-designed implementation-focused research is needed.

Table 4.

Considerations for Community Psychologists Wanting to Volunteer Within Corrections

| Community Agency and/or Academic Program |

|---|

| • Internal Capacity – By whom will your program be staffed and/or supervised? How often do you anticipate provider turnover? How will you handle training given your response to the prior questions? Is there a way to increase capacity by adding incentives (e.g., course credit or credit in teaching load, ability to use program data for research milestones or publications)? • Availability of Champions – Who will take the lead on all of the extra obligations that come with leading programming externally (beyond direct service time)? Does this person have strong interpersonal skills and investment? If not, are there other options? • Resources – What resources will support program implementation? Will you need to secure additional resources or funding for program implementation to be feasible? • Existing Relationships – Does your team have existing relationships that will facilitate your ability to partner with corrections? Consider connection through other community groups, coalitions, and committees or reaching out to organizations currently offering programming for advice if not. • Research Capacity – Do you have capacity to integrate research/evaluation as a routine part of the program? If not, is there an agency you can partner with to do this? |

| Carceral Setting |

| • Population Size and Characteristics – Are there enough people in the facility in need of your program? What are their priorities and existing obligations? Is the length of your program feasible given the population flow? • Degree of Capacity and Need for Community Engagement – Does the facility permit and/or encourage externally-facilitated programs? Through what office? What are the requirements and procedures for new volunteers? • Availability of Champions – Who will take the lead on shepherding your organization through approvals, recruitment, enrollment, and problem-solving facility challenges? • Climate – How supportive are the facility leadership and staff of your program? What internal barriers and facilitators are expected? How can barriers be problem solved? Are there any barriers that will prohibit implementation if not possible to overcome? • Research Support – Are you prepared to support research/evaluation? Are there formal processes/procedures outlined that can be shared with people implementing programs? |

| All Settings |

| • Mutual Goals – What are the mutual goals of each setting? If goals seem disparate, are there less obvious goals that might be facilitated if the program were to launch? How can each system help the other get credit for its commitment? • Communication – How do agencies typically prefer to communicate? Consider mode, frequency of contact, and individuals involved. How do preferred methods change in the case of urgencies or emergencies (e.g., suicidality, mandated reporting needs)? • Overlapping Availability – Are the schedules of both settings compatible? What competing programming or priorities might interfere program consistency? Can changes be made to decrease interference or better align schedules? |

Note: Program leaders should anticipate that responses to many of these considerations are likely to be dynamic and need to be re-evaluated periodically.

Our results also challenge beliefs that prisons do not meet standards for exposure therapy (Wolff et al., 2015) and that these interventions risk destabilizing residents if offered (Miller & Najavits, 2012). Rather, incarcerated women in our study described prison as an acceptable—and sometimes even advantageous—setting in which to complete SHARE, which is an exposure therapy. Our data converged with some points made in these past publications—we did find that lack of staff with formal training in mental health and lack of funding for training were reasons why NWACCC had not implemented trauma-focused therapy themselves. However, we also found that when a different implementation strategy was used (i.e., UAF student therapists providing therapy through NWACCC’s volunteer program), these limitations were easily overcome. Our results also highlighted several potential benefits of providing SVV interventions in carceral settings, where there are fewer barriers to therapy attendance and engagement. Offering trauma-focused therapy in carceral settings may be an important way to promote health equity—the community-academic partnership formed through SHARE allowed for highly marginalized people to access an evidence-informed treatment that likely would have otherwise been inaccessible. Moreover, the training opportunity SHARE provided led at least two former student therapists—who are now licensed clinical psychologists supervising their own students—to focus their careers on improving access to evidence-based therapy in carceral settings.

Given NWACCC’s heavy rehabilitative focus, it is tempting to assume that SHARE’s success would not be possible in other facilities. Although our study was limited to one facility and may not directly generalize to others, this hypothesis should be tested rather than assumed—and the voices of people who are incarcerated should be prioritized in the process. In light of the strong links between trauma exposure and incarceration, the question at hand should be how to best address these needs—not if it is possible. In our experience, it has been feasible to provide SHARE and other evidence-based therapies in carceral settings that were less treatment-oriented. Other study limitations include its retrospective nature and that PAH stakeholders interviewed were few. Some information about SHARE implementation may thus have been unavailable or misremembered. Study strengths included our use of a well-established framework throughout all phases of the study and the wide variety of stakeholders interviewed, which maximized perspectives on SHARE implementation and included the voices of incarcerated women.

In closing, we believe our study highlights the added value that community psychologists may find if they integrate implementation science in their work. Conducting process evaluation throughout implementation would maximize collection of knowledge on effective and ineffective strategies and corresponding factors. This kind of purposeful accounting of the dynamic factors that affect program outcomes will best prepare psychologists to pursue social justice endeavors.

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank the staff and residents at the Northwest Arkansas Community Corrections Center for their support and involvement in this project. The content and findings are the responsibility of the authors; Arkansas Community Corrections does not necessarily approve of or endorse these findings. We thank Geoffrey Curran, PhD, Jure Baloh, PhD, and the Center for Implementation Research at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) for their conceptual feedback. We also thank the members of the Health and the Legal System (HEALS) Lab at UAMS for their assistance with interview transcription.

Financial Disclosure: Execution of this study and manuscript preparation were supported by K23DA048162 (PI: Zielinski), R25DA037190 (PI: Beckwith), and T32DA022981 (PI: Kilts). During the development of this manuscript, Dr. Kirchner was supported by the Translational Research Institute (TRI), U54 TR001629 and UL1 TR003107, through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

A second, briefer interview guide was used to interview the two addiction recovery group leaders, who were not involved in SHARE implementation. These interviews were conducted to gather collateral information on NWACCC’s Inner Setting.

The Exploration and Preparation phases were asked about jointly.

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Mc Cue Horwitz S (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams GB, Etkind P, Burke MC, & Cram V (2008). Sexual violence and subsequent risk of sexually transmitted disease among incarcerated women. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 14(2), 80–88. doi: 10.1177/1078345807313797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aday RH, Dye MH, & Kaiser AK (2014). Examining the traumatic effects of sexual victimization on the health of incarcerated women. Women & Criminal Justice, 24(4), 341–361. doi: 10.1080/08974454.2014.909758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Back S, Dansky BS, Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Sonne S, & Brady KT (2000). Cocaine dependence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: A comparison of substance use, trauma history and psychiatric comorbidity. American Journal on Addictions, 9(1), 51–62. doi: 10.1080/10550490050172227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson J, & Carson A (2019). Prisoners in 2017.

- Dworkin ER, Menon SV, Bystrynski J, & Allen NE (2017). Sexual assault victimization and psychopathology: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 56, 65–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Ang A, Hillhouse M, & Rawson R (2013). Does posttraumatic stress disorder affect post-treatment methamphetamine use? Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 9(2), 123–128. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2013.779157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld LA, & Snell TL (2000). Women Offenders. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Grella CE, Stein J. a, & Greenwell L (2005). Associations among childhood trauma, adolescent problem behaviors, and adverse adult outcomes in substance-abusing women offenders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19, 43–53. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Branscomb-Burgess O, Gelaude DJ, Seth P, Parker S, & Fogel CI (2016). Risk profiles of women experiencing initial and repeat incarcerations: Implications for prevention programs. AIDS Education and Prevention, 28(4), 299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson ME, Bridges AJ, Bell J, & Petretic P (2014). Sexual violence therapy group in a women’s correctional facility: A preliminary evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 361–364. doi: 10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson ME, & Zielinski MJ (2018). Sexual victimization and mental illness prevalence rates among incarcerated women: A literature review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, Online first publication. doi: 10.1177/1524838018767933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Karlsson ME, Zielinski MJ, & Bridges AJ (2015). Expanding research on a brief exposure-based group treatment with incarcerated women. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 54(8), 599–617. doi: 10.1080/10509674.2015.1088918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson ME, Zielinski MJ, & Bridges AJ (2019a). Replicating outcomes of SHARE: A brief exposure-based group treatment for incarcerated survivors of sexual violence. Psychological Trauma: Theory , Research , Practice, and Policy. doi: 10.1037/tra0000504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Karlsson ME, Zielinski MJ, & Bridges AJ (2019b). Survivors Healing from Abuse: Recovery through Exposure. Unpublished Manual. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kubiak SP (2004). The effects of PTSD on treatment adherence, drug relapse, and criminal recidivism in a sample of incarcerated men and women. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(6), 424–433. doi: 10.1177/1049731504265837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SM, DeHart DD, Belknap J, Green BL, Dass-Brailsford P, Johnson KM, & Wong MM (2017). An examination of the associations among victimization, mental health, and offending in women. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(6), 796–814. doi: 10.1177/0093854817704452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Kileen T, Gros DF, Brady K ., & Back SE (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder and co-occurring substance use disorders: Advances in assessment and treatment. Clinical Psychology, 19(3), 1–27. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NA, & Najavits LM (2012). Creating trauma-informed correctional care: A balance of goals and environment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3, 17246. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, & Aarons GA (2019). Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science, 14, 1. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, … Kirchner JAE (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Grella CE, Dennis ML, & Funk RR (2014). Predictors of recidivism over 3 years among substance-using women released from jail. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(11), 1257–1289. doi: 10.1177/0093854814546894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff N, Huening J, Shi J, Frueh B, Hoover DR, & McHugo G (2015). Implementation and effectiveness of integrated trauma and addiction treatment for incarcerated men. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 30, 66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]