Abstract

Aim:

To conduct an integrative review of empirical studies examining factors affecting trust in the healthcare provider relationship among adolescents.

Design:

An integrative review was conducted.

Data Sources:

The keywords adolescent, trust, healthcare provider and related words were searched in multiple online research databases. The results were limited to research published between 2004–2019. Seventeen primary sources were identified and synthesized in the final review.

Review Method:

Guided by the Whittemore and Knafl integrative review method, a data-based convergent synthesis design was used to explore the key research question in both qualitative and quantitative research.

Results:

This integrative review found that health care provider behaviors, such as confidentiality, honesty, respect and empathy, promote adolescent’s trust of the healthcare provider. Notable gaps in the literature were also identified, including a lack of diversity among adolescent samples and healthcare provider types and underdeveloped measures of adolescent trust of healthcare provider.

Conclusion:

This integrative review informed the development of a new conceptual definition of adolescent trust of healthcare provider, which embodies the key findings of the importance of healthcare provider confidentiality, honesty, respect and empathy. This definition can be used to develop instruments, interventions and policies that promote healthcare provider trust among adolescents. Future research is needed to develop instruments to measure adolescents’ trust of healthcare providers, evaluate trust of healthcare providers among diverse samples of adolescents and evaluate adolescent trust of healthcare providers with a variety of healthcare provider types.

Impact:

The new conceptual definition of adolescent trust of healthcare provider can be used to enhance nursing practice and design behavioral interventions to improve trust of healthcare provider. To foster adolescent trust of healthcare provider, policies should be enacted in healthcare institutions to explain confidentiality, provide notification of reporting mandates and formalize consent, assent and dissent for adolescents seeking health care.

Keywords: adolescent, trust, confidentiality, honesty, respect, empathy, nurse, healthcare provider, integrative review, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Patient-centered healthcare is necessary to improve the quality of healthcare across the lifespan. Based on input from 25 nations, the World Health Organization established global standards for adolescent healthcare quality that promote patient-centered, developmentally-appropriate healthcare for youth (Nair et al., 2015). One of these standards is adolescent participation, which requires the adolescent’s trust of healthcare provider (HCP) as a prerequisite. Among adults, trust of HCP has been described as encompassing interpersonal and technical competence, moral comportment and vigilance (Murray & McCrone, 2015); however, it is unknown how trust of HCP is experienced and defined among adolescents. Many of adolescents’ developmental processes and associated health needs are consistent among youth around the world, which is signaled in the global standards for adolescent healthcare quality. Therefore, an international assessment of adolescent trust of healthcare provider was warranted.

Trust is a fundamental aspect of the relationship between an adolescent and their healthcare provider (HCP). As adolescents pass through the developmental period of skepticism that accompanies learning relativity (Steinberg, 2020), trust may become of greater concern. Legally, an adolescent minor cannot autonomously consent to all treatments; therefore, the adolescent’s relationship with the HCP is instead a contract between the adolescent’s parents and the HCP. As a result, adolescents may not inherently trust the HCP, which is compounded by the natural power differential between the HCP and adolescent. When a power differential exists, it is prudent for the vulnerable individual to be vigilant for violations of trust (Brennan et al., 2013). Variations in trust between adults and their HCPs has been noted in past studies and has similarly been observed in adolescents (Brennan et al., 2013; Hardin et al., 2018; Murray & McCrone, 2015). While several systematic reviews have examined adult trust of HCPs, none have examined adolescent trust of HCPs. This integrative review seeks to examine and address this gap in the literature.

BACKGROUND

An integrative review is a method that summarizes empirical or theoretical literature to develop a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon and builds nursing science by informing research, practice and policy initiatives (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Little is known about adolescents’ trust of HCPs; therefore, an integrative review design was used because the review method is broad enough to include primary sources using diverse methodologies while maintaining enough structure to remain focused on the primary topic. Whittemore and Knafl’s updated integrative review method (2005) identifies five stages of integrative review, including: (a) problem identification; (b) literature search; (c) data evaluation; (d) data analysis; and (e) presentation. An integrative approach enabled a comprehensive portrayal of both the quantitative and qualitative data available and studies that used quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. The problem identification stage includes identification of the variables of interest, the sampling frame and the review purpose. The literature search stage collects all relevant primary sources on the topic using multiple search strategies such as online databases, research registries and hand-searching reference lists of relevant literature. In the data evaluation stage, relevant data are extracted from literature sources and the quality of the data is evaluated and interpreted. Data from each source are categorized, coded and summarized into a single page in the data analysis stage. Then, the data are compared to identify patterns, themes and relationships in an effort to synthesize the evidence into general conclusions. Finally, the integrative review conclusions are presented in table format to show the logical sequence of evidence. This five-stage integrative review process was undertaken using key variables of interest—adolescent, trust and healthcare provider.

THE REVIEW

Aim

The aim of the integrative review was to conduct a systematic, interdisciplinary review of empirical literature examining trust of HCPs in adolescents. This study sought to: (a) conduct an integrative review of relevant empirical literature from multiple disciplines related to trust of HCPs in adolescents; (b) synthesize the empirical literature identified; and (c) identify gaps in the literature related to trust of HCPs in adolescents. In this review, adolescence was defined as including individuals 11–21 years old (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2017). The question used to guide the review was: How is trust in the HCP relationship conceptualized and experienced by individuals’ ages 11–21 years in the context of primary health care?

Design

An integrative review of trust of HCPs among adolescents was conducted using a data-based convergent synthesis design (Hong et al.,2017). This method was selected due to the broad nature of the research question and because it enabled a comprehensive synthesis of results into key groupings across studies that used quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches (Hong et al., 2017). Search methods and quality appraisal were designed to examine a variety of sources and research methods. The process for ensuring internal validity of the integrative review included at least two authors conducting and reconciling each at step: data extraction (HH and CH), quality appraisal (HH and AB) and synthesis of data (all authors).

Search Methods

An electronic literature search was conducted in April 2020 for relevant empirical literature in each of the following five databases: Cochrane, PsycInfo EBSCO, Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL and PubMed. The keywords “adolescent,” “trust,” and “healthcare provider” were each searched individually; then, the individual searches were combined with “and” to locate articles common to all three keywords. The searches were limited to the English language and publication dates were limited to between 2004 and 2019. The literature search was expanded to include related words to locate articles using variations of the search terms, such as distrust, youth, physician and nurse.

Search Outcome

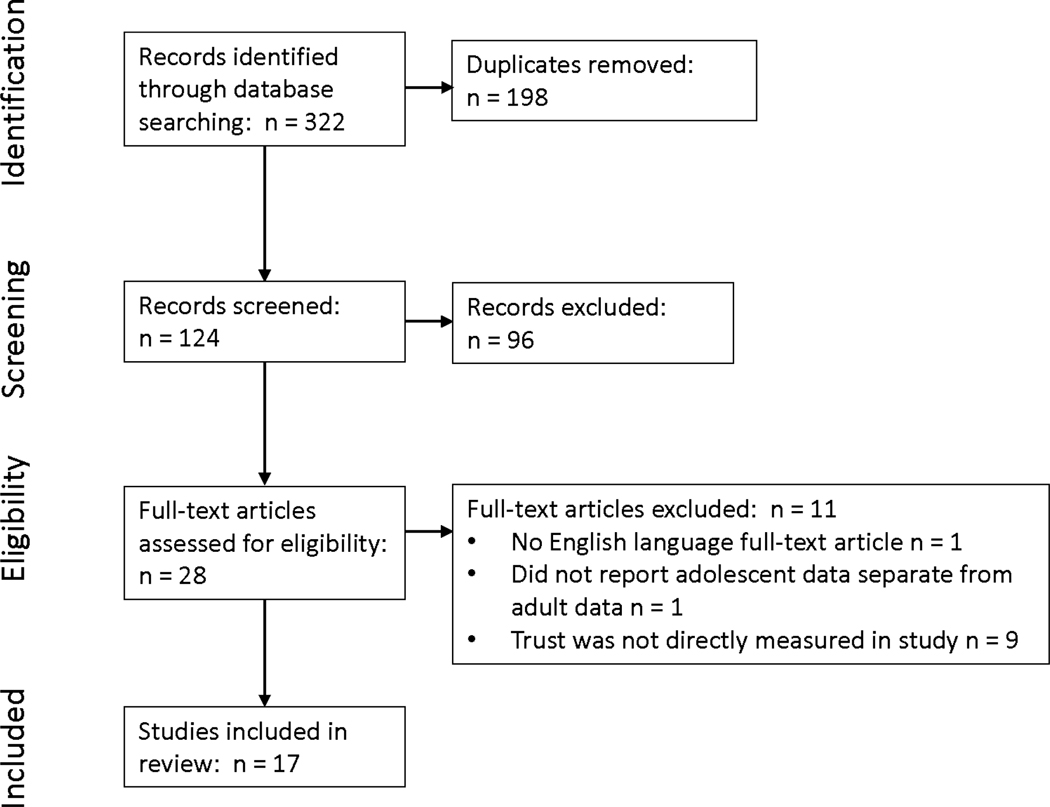

The electronic literature search of the five databases returned 322 abstracts. Titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine relevancy. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed journal articles, English language, the identified keywords listed above and qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. International studies that met inclusion criteria were included; while the healthcare systems between countries differ, many developmental and healthcare needs of adolescents translate across borders. Exclusion criteria were duplicate articles, grey literature, use of trust in a financial sense and inclusion of adolescent participants (ages 11–21) without reporting adolescent data separate from adult (>21 years old) data. The latter three exclusion criteria were selected to: ensure quality (included articles were evaluated in a peer-review publication process), tap into the relational trust experience between adolescents and their HCPs that was central to the research question and reflect unique adolescent experiences, respectively. Application of exclusion criteria resulted in 28 research reports for further screening. Each article was requested from the university library and then compiled in a binder in alphabetical order by the primary author’s name. One abstract did not have an English language translation, one article did not report adolescent data separate from adult data and nine articles discussed trust, but did not measure trust directly; therefore, these eleven abstracts were discarded, resulting in 17 articles remaining for review. See Figure 1 for the flow of literature through the search process (Moher et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of literature in the search process

Quality Appraisal

Gauging the quality of sources in an integrative review is complex but essential to sustaining the methodological rigor of the review. The literature was examined by two authors independently, using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) criteria established by Pluye and colleagues (2011). The MMAT provides appraisal guidelines for qualitative, quantitative and mixed method studies across multiple domains (e.g., study design, sampling, reliability/validity or rigor). For qualitative and quantitative (nonrandomized) studies, four different domains were assessed for each methodological approach; for mixed method studies, the four domains for both qualitative and quantitative domains (eight total) and an additional three domains specific for mixed methods studies were applied. No studies were excluded based on this data evaluation rating system; however, the quality appraisal was included as a variable in the data analysis stage to understand the limitations of the current level of evidence and identify avenues for future research (Supplemental Table 2).

Data abstraction and synthesis

Relevant articles were reviewed and data extracted from the publications using data extraction forms (see also Fleming et al., 2018). Data from primary sources included the study purpose, sample size, population focus, location, setting, methodology, study outcome variables and key findings related to trust of HCPs in adolescents. Data were compiled in a table format; Table 1 shows characteristics of included studies and Supplementary Table 1 displays data from each report by category. Using a data-based convergent synthesis design, two authors reviewed and compared the extracted data, then the data were compared to identify patterns, themes and relationships and the data were reviewed again to verify congruence with original primary sources. Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies were treated similarly during data extraction per the data-based convergent synthesis design (Hong et al., 2017). Key findings were categorized into six topics (defining characteristics of trust, age of adolescent, sex and gender identity, healthcare provider expertise, special populations and healthcare service type), which provided a structure through which to synthesize and discuss the data systematically. Reporting was informed by guidelines for reporting synthesis of quantitative studies by PRISMA (Moher et al., 2009) and qualitative studies by ENTREQ (Tong et al.,2012),

Table 1.

Empirical reports of trust in the healthcare provider relationship among adolescents

| Author(s), year | Sample, country, methodology | Variables associated to adolescent trust of healthcare provider (HCP) |

|---|---|---|

| Blake, Robley, & Taylor 2012 | Ages 13–17, HIV+, n = 18 United States Thematic analysis of focus groups and interviews |

Trust was built over time when HCPs supplied treatment, education, referrals, support, and patience without judgement Trust had an essential role in adherence to prescribed treatment |

| Breland-Noble, Burriss & Poole 2010 | Ages 11–17, African American, N = 28 United States Grounded theory analysis of focus groups and interviews |

Distrust of HCPs that failed to help or exacerbated their depressive symptoms Unwilling to trust those who betrayed their trust by sharing secrets or who would not make a genuine effort to listen and demonstrate care All quotes related to trust were made by 13 and 14 year old girls |

| Britto, et al. 2004 | Ages 11–19, chronic illness, N = 155 United States Self-administered quantitative written survey |

Trust of HCP measured using the Health Care Preference Measure Respect/trust was rated as the most important factor in healthcare preferences Respect/trust items measured honesty, competence, and empathy Lower parental education predicted greater adolescent preference for the respect/trust factor |

| Chandra & Minkovitz 2006 | Eighth grade students, N = 274 United States Self-administered quantitative written survey |

Trust of HCP measured using one item of HCP distrust Distrust of mental HCP was reported by 42.7%, which served as a barrier to seeking mental healthcare for half of those reporting distrust of HCP Girls were more likely than boys to identify interpersonal trust as influencing their help-seeking efforts for mental health concerns |

| Corry & Leavey 2017 | Ages 13–16, N = 54 United Kingdom Thematic analysis of focus groups |

Distrust of general HCPs related to psychological care included limited prior contact, anxiety about seeking help from general HCPs, confidentiality regarding parental involvement, professional competence Girls were more distrusting of general HCPs than boys |

| Farrant & Watson 2004 | Ages 13–18, chronic illness, N = 53 New Zealand Self-administered quantitative written survey |

Trust of HCP was measured using two items 75% of adolescents trusted HCP confidentiality, while 100% of parents trusted HCP confidentiality 19% of adolescents reported withholding information from the HCP due to a lack of trust Trust-building HCP qualities: ensuring confidentiality, listening well, and possessing good medical knowledge |

| Hardin, et al. 2018 | Ages 14–19, N = 224 United States Self-administered quantitative paper survey |

Trust of HCP was measured using the Wake Forest Interpersonal Trust of Physician’s Scale Adolescent characteristics predicting higher trust of HCP scores included having a HCP as a usual source of healthcare (rather than urgent care/emergency department), having private health insurance, healthier lifestyle behavior, and no difficulty finding transportation to HCP visits Higher levels of trust of HCP predicted healthier lifestyle behaviors Trust of HCP did not predict use of health services (HCP visits, emergency department visits) |

| Ingram & Salmon 2007 | Ages 13–21, N = 153 United Kingdom Thematic analysis of interviews and self-administered quantitative written surveys |

Trust of HCP was measured with a single item 100% trusted HCP at the No Worries clinic Participants preferred the close proximity, drop-in nature, confidentiality, professionalism, and friendly staff Participants report feeling more confident, more informed about sex and STIs, and less likely to take sexual risks |

| Klostermann, Slap, Nebrig, Tivorsak, & Britto 2005 | Ages 11–19, healthy and with chronic conditions, N = 54 United States Thematic analysis of focus groups |

Younger adolescents were more concerned about confidentiality than older adolescents Adolescents with chronic illness expressed more desire for parental involvement in health care than healthy adolescents Adolescents with chronic illness were also more likely to value HCP honesty and advocacy 4–5 HCP visits to determine trustworthiness of HCP HCP behaviors to improve trust include being truthful, friendly, reliable, asking for the adolescent’s opinion, keeping private information confidential, not withholding information, and engaging in small talk to show concern Violations of trust included medical mistakes, breaches of confidentiality, and taking advantage of vulnerable patients Increasing age was modestly associated with an increase in trust of HCP |

| Leavey, Rothi, & Paul 2011 | Ages 14–15, N = 48 United Kingdom Self-administered quantitative written survey and content analysis of focus groups |

Trust of HCP measured by help-seeking around a range of health concerns Trust meant the general HCP kept information private and confidential from the adolescents’ family members Participants recommended focusing on getting to know the general HCP during the first visit Participants perceived general HCPs as specializing in physical illness only and did not trust general HCPs to help with emotional difficulties |

| Majumder, et al. 2018 | Ages 15–18, refugee adolescents, N=15 United Kingdom Thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews |

Refugees often lacked trust in mental HCPs Most refugee lacked experience with mental HCPs in their home country Cultural differences between the adolescent and mental HCP contributed to adolescents’ distrust Refugee adolescents did not feel safe with mental HCPs in their host country; immigration status did not appear to influence adolescents’ trust Traumatic experiences experienced by the participants contributed to feeling unsafe and distrust |

| McKee & Fletcher 2006 | Ages 13–19, low income, ethnic minority, N = 819 United States Computer-assisted, self-report survey |

Trust of HCPs was assessed with two investigator-developed items Most participants (89%, 85.4%) reported agreement with the trust Trust of HCPs did not predict forgone care and did not differ for participants with and without a usual source of care Trust of physicians was associated with self-efficacy for confidential care Older girls were more likely to report experiencing confidential care |

| McKee, Fletcher, & Schechter 2006 | Ages 13–19, low income, ethnic minority, N = 819 United States Computer-assisted, self-report survey |

Trust of HCPs was assessed with two investigator-developed items Trust of HCP did not predict time to initiation of gynecologic care |

| Renker 2006 | Ages 18–20, history of perinatal violence, N = 20 United States Content analysis of semi-structured interviews |

Distrust of HCP occurred due to confidentiality concerns, and fear of abuse being reported to authorities by HCP, which may result in retaliation from the abuser Distrust of authority figures—including HCPs—prevents adolescents from acknowledging the abuse One negative experience with an authority figure results in diminished trust of all authority figures |

| Saftnery, Martyn, & Momper 2014 | Ages 15–19, American Indian, N = 20 United States Ground theory analysis of interviews and talking circles |

Girls reported trust of HCP was influenced by HCP honesty, confidential care, nonjudgmental, and comprehensive healthcare |

| Scott & Davis 2006 | Ages 18–19, African-American males transitioning out of foster care, n = 74 United States Quantitative survey |

Mistrust was measured with the interpersonal relations subscale of the Cultural Mistrust Inventory modified to measure mistrust of mental HCPs (α = .78) Participants reported a modest level of cultural mistrust of white mental HCPs Cultural distrust was associated with negative social contextual experiences |

| van Staa, Jedeloo & van der Stege 2011 | Ages 12–19, chronic conditions, N = 1055 Netherlands Quantitative survey and thematic analysis of interviews |

Chronically ill adolescents ranked being trustworthy and honest was the second highest desired HCP quality Participants desired a mutually trusting relationship with their HCP identified as honest and confidential Boys attached more importance to the trustworthiness, honesty, and professional expertise of HCPs than did girls Girls preferred more attention to older children and rated listening as a more important provider quality than boys Older adolescents had a stronger preference for staff being focused on them (rather than parents) and listening to them, while younger adolescents were more concerned about staff kindness |

RESULTS

The sample of research articles examining trust of HCPs in adolescents included 17 studies. A total of six quantitative studies, seven qualitative studies and four mixed methods studies were included and reflected research conducted in the Netherlands, New Zealand, United Kingdom and the United States. Guided by a data-based convergent synthesis design, a constant comparison method was used to evaluate categorized data (Hong et al., 2017). In this evaluation, data were compared and contrasted by sample characteristics and healthcare service type to identify patterns, themes and relationships.

Defining Characteristics

Frequently reported characteristics defining trust of HCP in adolescents included confidentiality, honesty, respect and empathy. Confidentiality was reported most often by adolescents as a defining characteristic of trust of their HCPs (Breland-Noble et al., 2010; Corry & Leavey, 2017; Farrant & Watson, 2004; Ingram & Salmon, 2007; Klostermann et al., 2005; Leavey, et al., 2011; McKee & Fletcher, 2006; Renker, 2006; Saftner et al,2014; van Staa et al., 2011). Adolescents defined confidentiality as maintaining the privacy of the secrets disclosed to the HCP from family members and authorities (Breland-Noble et al., 2010; Farrant & Watson, 2004; Leavey et al., 2011; Renker, 2006). Honesty was also identified as a building block of trust and meant telling the truth and not withholding information, as well as notifying the adolescent of reporting mandates prior to assessing sensitive information (Britto et al., 2004; Corry & Leavey, 2017; Klostermann et al.; Renker 2006; van Staa et al., 2011). Respect meant two-way, equal communication and valuing the adolescent’s opinion (Britto et al., 2004, Klostermann et al., 2005; McKee & Fletcher, 2006). Empathy was characterized as making a genuine effort to listen and demonstrating concern (Britto et al., 2004, Breland-Noble et al., 2010; Klostermann et al., 2005).

Like the results identified here, Rotenberg (2010) theorized children and adolescents’ trust of others in general is framed by the concepts of honesty, reliability and emotional connection. In Rotenberg’s framework of trust, confidentiality is complementary to honesty and empathy was encompassed within the emotional connection concept (2010). These characteristics were also mentioned in theories of adult trust of HCPs (Bova et al., 2006; Hall, 2001; Kao et al., 1998), which highlights the importance of these components of trust across both adolescents and adults. However, across studies included in this review, confidentiality was consistently indicated as the most salient element of trust of HCPs in adolescents. The same foregrounding of confidentiality was not observed in theoretical framings of adult trust of HCPs, highlighting the particular concern of this facet of trust with HCPs in adolescents.

Adolescent Age

Theory suggests trust beliefs change as young people pass through early adolescence and are associated with developmental skepticism, imaginary audience, self-consciousness and increased risk behaviors (Chandler, 1987; Steinberg, 2020). There is preliminary evidence associating age and trust of HCPs in adolescents. A survey measuring trust of HCPs to maintain confidentiality reported that adolescents 13 to 18 years old were less trusting of their HCPs than their parents (Farrant & Watson, 2004). An age-specific analysis of focus groups that explored how adolescents perceive HCP trust revealed that increasing age was modestly associated with an increase in trust (Klostermann et al., 2005). Adolescents taking part in focus groups identified quotes from youths 13 to 14 years old that expressed low levels of trust of HCP (Breland-Noble et al., 2010). However, a survey measuring trust of HCPs among youths 14 to 19 years old showed no difference in trust of HCP scores by age (Hardin et al., 2018), nor did a survey of low-income, sexually active girls 13–19 years old seeking gynecological care (McKee & Fletcher, 2006). Alternatively, in a survey of healthcare preferences in adolescents ages 12 to 19 years old with a chronic condition, older age was strongly associated with concerns around communication and listening, while younger adolescents reported greater concerns about empathy and kindness of HCPs (van Staa et al., 2011). Preliminary evidence suggests older adolescents may have greater trust of HCPs than younger adolescents; however, adolescents’ concerns with specific components of HCP trust may change with age.

Sex and Gender

There is conflicting evidence concerning the influence of sex and gender on trust of HCPs in adolescents. Focus groups exploring adolescents’ attitudes toward HCPs reported that girls were more distrusting of HCPs than boys (Corry & Leavey, 2017). In focus groups conducted with adolescents, quotes questioning the trustworthiness of HCPs were made only by girls (Breland-Noble et al., 2010). Girls were more likely than boys to identify trust as influencing their help-seeking efforts for mental health concerns (Chandra & Minkovitz, 2006). However, in a survey of adolescents 14 to 19 years old, there were no differences in trust of HCP score by sex (Hardin et al., 2018). A healthcare preferences survey found that boys attached more importance to the trustworthiness, honesty and professional expertise of HCPs than girls, while girls rated kindness and listening as a more important HCP quality than boys (van Staa et al., 2011). More girls than boys also reported concern that HCPs provide greater attention to the needs of older adolescents (van Staa et al., 2011). Several of the reviewed studies evaluated a single gender, which prevented comparison between boys and girls (McKee & Fletcher 2006; McKee et al., 2006; Renker 2006; Saftner et al., 2014; Scott & Davis, 2006). None of the reviewed studies assessed either sexual orientation or gender identity of the adolescent or HCP.

Healthcare Provider Expertise

There is some preliminary evidence that adolescents may experience greater trust of pediatric HCPs than family or adult HCPs. Most of the studies reviewed did not ask the adolescents whether their HCP had expertise in pediatric health care. However, a few studies focused on adolescents attending pediatric clinics, while a few others focused on adolescents seeing family HCPs.

Adolescents treated by pediatric HCPs report mixed levels of trust. A study of adolescents with chronic conditions at a specialty pediatric clinic revealed a strong preference for HCPs who are trustworthy (van Staa et al., 2011). At an adolescent sexual health clinic, all participants reported trusting the HCP, which the authors suggest was a result of explicit confidentiality assurance (Ingram & Salmon, 2007). A study of adolescent refugees receiving mental health treatment from HCPs reported a strong distrust of HCPs (Majumder, et al., 2018); however the authors suggested the distrust may have been related to both recent traumatic experiences and cultural beliefs about mental health. The limited evidence is unclear concerning adolescents’ trust of pediatric HCPs.

Among studies focusing on adolescent trust of family HCPs, two studies were reviewed, both of which focused on mental health issues. A focus group study of adolescents’ attitudes toward consulting family HCPs about mental health issues revealed distrust due to confidentiality concerns and parents also receiving care from the same HCP (Corry & Leavey, 2017). Similarly, a mixed method study of adolescents’ help-seeking preferences about mental health concerns revealed a strong distrust of the family HCP to keep information confidential from both immediate and extended family members (Leavey, et al., 2011). The limited evidence suggests adolescents do not trust that family HCPs will maintain confidentiality from other family members. These results may also echo mental health stigma, rather than a reflection of adolescents’ trust of family HCPs.

Specialized Adolescent Populations

In this review, studies examined trust of HCPs among specialized adolescent populations defined by race/ethnicity, immigration status and urban versus rural residence. Two studies of African-American adolescents demonstrated a lack of trust in HCPs (Breland-Noble et al., 2010; Scott & Davis, 2006). African-American adolescents diagnosed with depression reported distrust of HCPs who failed to help in managing their depressive symptoms, while African-American adolescent males transitioning out of foster care reported a cultural mistrust of mental HCPs (Breland-Noble et al., 2010; Scott & Davis, 2006). Similar cultural distrust was also reported among unaccompanied refugee adolescents primarily from Afghanistan (Majumder et al., 2018). This group of adolescents reported similar distrust and concerns around receipt of mental health services, attributing this, in part, to cultural differences between themselves and their HCPs.

Two other studies drawn from a single dataset described moderately high trust of HCPs among a mostly Hispanic adolescent female sample (McKee & Fletcher 2006; McKee et al. 2006). These studies reported that 89% of Hispanic adolescent females trusted HCPs, in general. McKee et al. (2006) determined that trust of HCPs did not affect use of reproductive healthcare services within the sample. Interviews with Native American girls reported high levels of trust of female HCPs when accessing sexual health services (Saftner et al., 2014).

The integrative review also captured similarities and differences among rural- and urban-dwelling adolescents and HCP trust. For adolescents residing in rural areas, healthcare access and lifestyle behaviors were significantly predictive of HCP trust (Hardin, et al., 2018). Adolescents with a usual source of health care, with private health insurance coverage, that reported higher levels of healthy lifestyle behaviors and no transportation difficulty were more likely to report higher levels of HCP trust (Hardin et al., 2018). Healthcare accessibility (e.g., convenience of health center location, payment for services) also emerged as an important theme in a study among urban Native American girls (Saftner et al., 2014). These adolescents reported that access to trusted HCPs was an essential component of being able to maintain their health and well-being.

Mental Health

Four studies showed a lack of trust of mental HCPs in adolescents (Breland-Noble, Burriss, & Poole, 2010; Chandra & Minkovitz, 2006; Farrant & Watson, 2004; Leavey, et al., 2011). In one study, nearly 43% of those adolescents surveyed reported distrust of mental HCPs and of those reporting distrust, more than half were unwilling to use mental health services if needed (Chandra & Minkovitz, 2006). Across studies, multiple reasons were cited for this distrust of mental HCPs and reticence to reach out for mental health services. Two studies highlighted adolescents’ concerns around receiving competent, effective mental health services (Breland-Noble et al., 2010; Leavey et al., 2011). A grounded theory analysis of African-American adolescents diagnosed with depression revealed distrust of HCPs who exacerbated or failed to help their depressive symptoms, or had breached their trust previously (Breland-Noble et al., 2010). A study with British adolescents in secondary school reported low levels of trust in general HCPs to provide mental health care because they were perceived as specializing in physical illness and lacking skills to treat mental illness (Leavey et al., 2011). Accessibility of mental health services also emerged as a barrier to HCP trust. Finally, one study of adolescents with chronic illness in New Zealand demonstrated adolescents’ desire to discuss mental health concerns with their HCPs, but they did not have the opportunity to do so (Farrant & Watson, 2004).

Taken as a whole, the results of these studies suggest widespread distrust of mental HCPs in adolescents. There are multiple possible reasons for this distrust. First, adolescents may fear being stigmatized for presenting mental health concerns and experience uncertainty about the HCP’s qualifications to care for mental health concerns. Alternatively, lack of trust in HCPs—and others—may be a symptom of mental illness and may be reported irrespective of the actual performance and quality of care offered by the HCP.

Chronic Conditions

Six studies measured HCP trust in adolescents with chronic conditions (Blake et al. 2012; Britto et al. 2004; Farrant & Watson, 2004; Klostermann et al., 2005; van Staa et al., 2011). In a study of American adolescents with chronic conditions, healthcare preferences were measured with a scale containing three subscales (respect/trust, power/control, caring/closeness). Participants rated the respect/trust subscale (α = .86) as the most important of the three factors (Britto et al., 2004). Of five HCP qualities (competence, trust/honesty, kindness/reassurance, patience and personal attention), adolescents with chronic conditions in the Netherlands rated trust/honesty as the second most important HCP quality, following HCP competence (van Staa et al., 2011). Focus groups with HIV+ youth showed that trusting relationships were built over time when HCPs supplied health services without judgment and a trusting relationship with an HCP influenced the adolescent’s adherence to prescribed treatment (Blake et al. 2012). A survey of New Zealand adolescents with chronic conditions revealed that a quarter of the participants did not trust their HCPs to keep information confidential and 19% of the participants withheld information from their HCPs due to that lack of trust (Farrant & Watson, 2004). However, comparisons between healthy adolescents and adolescents with chronic conditions in the U.S. revealed that adolescents with chronic conditions are more interested in having parents involved in their health care than healthy adolescents (Klostermann, et al., 2005). The evidence presented in these studies revealed that adolescents with chronic illness highly value mutual trust in the HCP relationship, honesty, listening skills, professional competence and may prefer greater parental involvement in health care. Honesty may be of greater concern in the adolescent chronic condition population due to the possibility of receiving bad news. The preference for parental involvement in adolescents with a chronic condition is contrary to the preferences of healthy adolescents and is likely a result of the serious nature of the chronic condition. These results also provide preliminary evidence that an adolescent’s trusting relationship with an HCP supports adherence to prescribed treatment.

Reproductive Health Care

Four studies concerning adolescent trust of reproductive HCPs were evaluated (Ingram & Salmon, 2007; McKee et al., 2006; Renker, 2005; Saftner et al., 2014). Two studies of adolescents receiving reproductive health care reported high levels of HCP trust, which was accompanied by high levels of perceived accessibility and confidentiality (Ingram & Salmon, 2007; Saftner etal., 2014). Girls with a history of experiencing domestic abuse attending a gynecology clinic reported one negative experience with an authority figure resulted in diminished trust of all authority figures (Renker, 2005). One study by McKee et al. reported that trust of HCPs had no influence on use of reproductive care, although the measure of trust of HCPs may have been inadequate (2006). The results of these studies suggest that confidentiality and accessibility significantly influence adolescents’ trust of reproductive HCPs.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of these empirical studies illuminates several important issues. First, significant differences are evident between adolescents seeking general, reproductive, or mental health care and those adolescents seeking health care for a chronic illness. The adolescents with chronic illness report a preference for parental involvement, which contradicts the preferences of adolescents accessing general, reproductive, or mental health care. This evidence suggests adolescents make conscious decisions in determining which health concerns to share with and entrust to their parents. It also demonstrates adolescents have strong preferences concerning healthcare autonomy, privacy and confidentiality.

In addition, concern exists regarding distrust of HCPs among specialized adolescent populations. Two studies of African-American adolescents demonstrated consistent distrust of health care providers (Breland-Noble et al., 2010; Scott & Davis, 2006). By contrast, a sample of Hispanic adolescent females and a sample of Native American adolescents indicated moderately high trust of HCPs that had no effect on use of health services (McKee & Fletcher, 2006; McKee et al., 2006; Saftner et al., 2014). Both rural- and urban-dwelling adolescents emphasized the importance of healthcare access in determining HCP trust (Hardin, et al., 2018; Saftner et al., 2014).

Research of both general trust and trust of HCPs has suggested older adolescents may be more trusting than younger adolescents (Klostermann, et al., 2005; Rotenberg, 2010; van Staa et al., 2011). These results reflect theoretical evidence concerning developmental skepticism, increased risk behaviors, imaginary audience and associated self-consciousness that affects the first half of adolescence (Steinberg, 2020). However, this review revealed conflicting evidence concerning changes in trust of HCP as adolescents age. One study suggested older and younger adolescents’ concerns with specific components of HCP trust (confidentiality, honesty, empathy, respect) varies. The lack of instruments to measure trust of HCPs in adolescents and the lack of longitudinal studies likely contributed to this lack of clarity concerning age and trust of HCP.

It is unknown if trust of HCPs changes across sex or gender identity of either the adolescent or HCP. No studies of adolescent trust of HCPs measured gender identity and no studies used a measure of trust of HCPs designed for adolescents. The lack of evidence may be due to the insensitivity of instruments measuring trust of HCP. Alternatively, adolescents’ concerns with specific components of HCP trust may differ across sex and/or gender identity. Clarifying the role of biological and social influences on trust of HCPs would allow clinical interventions to be developed and tested, along with institutional and governmental policies to promote adolescent-HCP trust.

Limitations

Limitations exist in this integrative review of trust of HCPs in adolescents. Ideally, all relevant literature is included in a review, but it is likely more studies that are eligible exist. Future efforts should identify and obtain additional eligible studies through methods such as hand-searching of key, relevant journals and citations listed in relevant systematic reviews. A dearth of empirical evidence concerning trust of health care in adolescents exists, which results in significant gaps in the literature. The sample of empirical reports included in this review also lacks adequate participant diversity, which limits the generalizability of the findings detailed herein. None of the studies included explored other factors of diversity, such as sexual orientation or membership in a religious minority. These factors, as well as others (e.g., ethnicity, experiences of trauma), should be examined to best understand trust of HCPs among diverse population samples.

Most (82%) of these studies were composed of small samples (< 500 participants) and the quality and rigor of the studies varied; therefore, the findings in this study should be interpreted with some caution. Only two of the nine quantitative studies used a valid and reliable measurement tool to measure trust of HCPs (Hardin, et al., 2018; Scott & Davis, 2006), but neither of those measures were designed with adolescents in mind. In one study, trust of HCPs was measured with two investigator-developed items and the authors suggested the measure of trust of HCPs may have been inadequate (McKee & Fletcher, 2006). Trust of HCPs in adolescents should be measured with a valid and reliable instrument that reflects the defining characteristics of trust of HCP (confidentiality, honesty, respect, empathy) identified here. Existing instruments measuring trust of HCPs that were designed for adults do not contain measures for all four characteristics of adolescent trust of HCPs (Anderson & Dedrick, 1990; Bova, et al., 2006; Hall et al., 2002; Kao, et al., 1998). Future research should include longitudinal studies using a psychometrically valid and developmentally appropriate measure of trust of HCPs to evaluate how sex, gender identity and age influences trust of HCPs among diverse samples of adolescents. The Health Care Preferences Questionnaire (α = .78–.90), which was designed to rank the healthcare preferences of adolescents with chronic illness, contains a “respect/trust” subscale and the remaining subscales (power/control, caring/closeness) encompass the concepts of confidentiality, honesty and empathy (Britto et al., 2004). Revising the Health Care Preference Questionnaire to function as a measure of adolescent-specific trust of HCPs is one potential solution.

CONCLUSION

This review shows that adolescents place great emphasis on confidentiality, honesty, empathy and respect in their relationships with HCPs, which varies from the definition identified among adults—interpersonal and technical competence, moral comportment and vigilance (Murray & McCrone, 2014). This is likely a result of developmentally appropriate issues of skepticism, independence and identity (Erikson, 1963; Chandler, 1987; Havighurst, 1953). The power dynamic between the adolescent and the HCP is such that it will require the HCP to clearly state parameters around the provider-patient relationship (e.g., mandated reporting guidelines), to verbalize promises, demonstrate reliability and ensure confidence prior to developing an adolescent’s trust.

The findings of this review of the literature suggest that to promote the trust of the adolescent patient, an HCP must: (1) maintain the patient’s confidentiality of sensitive information from family members and authorities; (2) honestly disclose pertinent information to adolescent patients and notify them of any reporting mandates prior to assessing sensitive information; (3) use respectful, two-way communication that values the adolescent’s opinion; and (4) make a genuine effort to listen and demonstrate empathy. Interventions to establish, maintain, or improve trust should focus on these modifiable behaviors (Murray & McCrone, 2015) and adolescents’ access to HCP services (transportation, location, payment). To measure the degree of trust among HCPs and adolescents, reliable and valid instruments should be developed and tested among diverse samples with various provider types. Policies enacted in healthcare institutions that explain confidentiality, disclose reporting mandates and formalize consent, assent and dissent for adolescents seeking health care may also influence trust of HCPs. Implementing these practices and policies may significantly lessen adolescent anxiety, while increasing trust and disclosure for improved adolescent health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge Matt McManus for his editorial services.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [1T32NR015433] and the Rural Nurses Organization [small grant].

Author Contributions: All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria (recommended by the ICMJE*):

substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

*http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/

| Criteria | Author Initials |

|---|---|

| Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; | HH, AB, CH, BH |

| Involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; | HH, AB, CH, BH |

| Given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; | HH, AB, CH, BH |

| Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. | HH |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Contributor Information

Heather K. HARDIN, Case Western Reserve University, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing.

Anna E. BENDER, Case Western Reserve University, Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences.

Carla P. HERMANN, Indiana University, School of Nursing.

Barbara J. SPECK, University of Louisville, School of Nursing.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2017). Bright futures guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents. Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, & Dedrick RF (1990). Development of the Trust in Physician scale: A measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychological Reports, 67(3), 1091–1100. 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake B, Robley L, & Taylor G (2012). A lion in the room: Youth living with HIV. Pediatric Nursing, 38(6), 311–318. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23362629 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bova C, Fennie KP, Watrous E, Dieckhaus K, & Williams AB (2006). The health care relationship (HCR) trust scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 477–488. 10.1002/nur.20158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland-Noble AM, Burriss A, & Poole HK (2010). Engaging depressed African American adolescents in treatment: Lessons from the AAKOMA PROJECT. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(8), 868–879. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan N, Barnes R, Calnan M, Corrigan O, Dieppe P and Entwistle V (2013). Trust in the health-care provider–patient relationship: A systematic mapping review of the evidence base, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 25(6), 682–688. 10.1093/intqhc/mzt063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto MT, DeVellis RF, Hornung RW, DeFriese GH, Atherton HD, & Slap GB (2004). Health care preferences and priorities of adolescents with chronic illnesses. Pediatrics, 114(5), 1272–1280. 10.1542/peds.2003-1134-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M (1987). The Othello effect: Essay on the emergence and eclipse of skeptical doubt. Human Development, 30, 137–159. 10.1159/000273174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A & Minkovitz CS (2006). Stigma starts early: Gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(6), 754e751–758. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry DAS, & Leavey G (2017). Adolescent trust and primary care: Help-seeking for emotional and psychological difficulties. Journal of Adolescence, 54, 1–8. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1963). Childhood in Society. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Farrant B, & Watson PD (2004). Health care delivery: Perspectives of young people with chronic illness and their parents. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 40(4), 175–179. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming K, Booth A, Hannes K, Cargo M, & Noyes J (2018). Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series—paper 6: reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation and process evaluation evidence syntheses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 97, 79–85. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA (2001). Do patients trust their doctors? Does it matter? North Carolina Medical Journal, 62(4), 188–191. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.11002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, & Mishra AK (2001). Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured and does it matter? Milbank Quarterly, 79(4), 613–639. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.11002.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, Camacho F, Kidd KE, Mishra A, & Balkrishnan R (2002). Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Medical Care Research & Review, 59(3), 293–318. 10.1177/1077558702059003004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin HK, McCarthy VL, Speck BJ, & Crawford TN (2018). Diminished trust of healthcare providers, risky lifestyle behaviors and low use of health services: A descriptive study of rural adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing, 34(6), 458–467. 10.1177/1059840517725787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havighurst R (1953). Human Development and Education. New York: Longmans, Green & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, & Wassef M (2017). Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: Implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Systematic Reviews, 6(61), 1–14. 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J, & Salmon D (2007). ‘No worries!’: Young people’s experiences of nurse-led drop-in sexual health services in South West England. Journal of Research in Nursing, 12(4), 305–315. 10.1177/1744987107075583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kao AC, Green DC, Davis NA, Koplan JP, & Cleary PD (1998). Patients’ trust in their physicians: Effects of choice, continuity and payment method. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 13(10), 681–686. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00204.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann BK, Slap GB, Nebrig DM, Tivorsak TL, & Britto MT (2005). Earning trust and losing it: Adolescents’ views on trusting physicians. Journal of Family Practice, 54(8), 679–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavey G, Rothi D, & Paul R (2011). Trust, autonomy and relationships: The help-seeking preferences of young people in secondary level schools in London. Journal of Adolescence, 34(4), 685–693. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder P, Vostanis P, Karim K, & O’Reilly M (2019). Potential barriers in the therapeutic relationship in unaccompanied refugee minors in mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 28(4), 372–378. 10.1080/09638237.2018.1466045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee MD, & Fletcher J (2006). Primary care for urban adolescent girls from ethnically diverse populations: Foregone care and access to confidential care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 17(4), 759–774. 10.1353/hpu.2006.0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee MD, Fletcher J, & Schechter CB (2006). Predictors of timely initiation of gynecologic care among urban adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(2), 183–191. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & Group P (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. British Medical Journal, 339, b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray B, & McCrone S (2015). An integrative review of promoting trust in the patient-primary care provider relationship. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(1), 3–23. 10.1111/jan.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair M, Baltag V, Bose K, Boschi-Pinto C, Lambrechts T, & Mathai M (2015). Improving the quality of health care services for adolescents, globally: A standards-driven approach. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(3), 288–298. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, … Rousseau MC (2011). Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Retrieved from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com

- Renker PR (2006). Perinatal violence assessment: Teenagers’ rationale for denying violence when asked. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 35(1), 56–67. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00018.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg K (2010). Interpersonal Trust During Childhood and Adolescence. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saftner MA, Martyn KK, & Momper SL (2014). Urban dwelling American Indian adolescent girls’ beliefs regarding health care access and trust. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 3(1), 1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD, & Davis LE (2006). Young, black and male in foster care: Relationship of negative social contextual experiences to factors relevant to mental health service delivery. Journal of Adolescence, 29(5), 721–736. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2020). Adolescence. New York, NY: McGraw-HIll. [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, & Craig J (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(181), 1–8. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staa AL, Jedeloo S, & van der Stege H (2011). “What we want”: Chronically ill adolescents’ preferences and priorities for improving health care. Patient Preference and Adherence, 5, 291–305. 10.2147/PPA.S17184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemoore R, & Knafl KA (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.