Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is a curative-intent therapy for patients with hematological malignancies, but despite advances in the field in recent years, there is still a significant risk of post-transplant mortality. In addition to relapse of the underlying malignancy, the key contributors to this high mortality are graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and infection. The intestinal microbiota is the collective term describing the community of bacteria, fungi, viruses and protozoa that resides in the human gastrointestinal tract. Bacterial communities have been studied most comprehensively, and disruption of these communities has been associated with the development of a variety of medical conditions in large clinical associative studies. Preclinical studies suggest a mechanistic role for the intestinal microbiota in the instruction and maintenance of both intestinal and systemic immune cell function. This review outlines our current understanding of the relationship between gut bacteria and allo-HCT outcomes, including infection, immune reconstitution, GVHD and relapse, drawing on evidence from both clinical associative studies and preclinical mechanistic studies.

Introduction

The digestive tract harbors the largest microbial community of the mammalian body, and these micro-organisms have significant capacity to interact with and influence their host, due to direct contact with both parenchymal and hematopoietic cell populations, and their capacity to produce circulating metabolites. Advances in sequencing technologies in recent years have facilitated the rapid progress of clinical associative studies and these, in turn, have served as valuable hypothesis-generating tools for mechanistic studies in preclinical animal models.

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is a curative-intent treatment for patients with hematological malignancies. However, it is a high-risk therapy, as overall post-transplant mortality remains in the order of 50%, most commonly due to disease progression or relapse, infection and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [1]. Microbial diversity, a summary measurement of the richness and evenness of unique bacterial taxa, is a useful measure of intestinal microbiota health. Several groups have observed a decline in intestinal microbial diversity manifesting early in the course of allo-HCT, and this injury to the intestinal microbiota is associated with lower overall survival after allo-HCT [2, 3]. Exposures to broad-spectrum antibiotics are associated with a decrease in the intestinal microbiota biodiversity during allo-HCT, although other factors such as dietary changes, conditioning regimens and other medications are likely to influence the post-HCT intestinal microbiota dynamics (Table 1) [4, 5].

Table 1.

Potential modulators of the intestinal microbiota during allo-HCT

| Factors | Impacts | References |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | ||

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics (β-lactam, metronidazole, meropenem) | Broad-spectrum antibiotics target obligate anaerobes which are typically producers of short-chain fatty acids in the gut and allows the expansion of opportunistic pathogens | [4, 55] |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | Imipenem-cilastatin treatment in mice leads to expansion of the mucus-degrading bacteria Akkermansia | [55] |

| Fluoroquinolones | Prophylactic fluoroquinolones lead to a decreased risk of intestinal domination by Gram-negative bacteria | [10] |

| Transplant-associated factors | ||

| Conditioning chemotherapy: carmustine, etoposide, aracytin and melphalan | After conditioning, the intestinal microbiota diversity declined, accompanied by a decrease in Faecalibacterium abundance and an increase in Escherichia abundance | [72] |

| Conditioning intensity | Patients receiving non-myeloablative conditioning regimens have higher intestinal diversity at engraftment time compared to patients receiving myeloablative conditioning regimens | [5] |

| Total body radiation | Total body radiation in mice leads to reduction in the intestinal microbiota diversity and a shift in the overall microbial compositions compared to controls | [73] |

| Immuno-suppressive medications (methotrexate, cyclosporine A) | In a high-throughput in vitro drug screen, some human-target drugs show antibacterial activities to some commensal bacterial strains often found in the human gut | [74] |

| Diet | ||

| Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) | Use of long-term TPN (≥10 days) is associated with a loss of Blautia | [8] |

| Western diet/Fiber-free diet | Mice fed on a prolonged fiber-free diet experience decreased intestinal microbiota diversity, a decrease in Bifidobacteria and an increase in mucus-degrading Akkermansia | [30,31] |

| Dietary fiber inulin supplementation | Inulin supplementation restores mucus functions in mice fed on a Western diet and restore microbiota loads | [75] |

| High-fiber (pectin, cellulose) diet | High-fiber diets containing cellulose and pectin lead to increased cecal and systemic levels of short-chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate and butyrate | [76] |

| Host genetics | ||

| rs4988235 SNP conferring lactase expression and lactose intolerance in European populations | C/C SNP is associated with non-absorbers of lactose and increased risk of Enterococcus domination after allo-HCT | [54] |

| Paneth cell ⍺-defensin-5 gene SNPs | rs4415345G is associated with a higher abundance of a butyrogenic obligate anaerobe, Odoribacter splanchnicus, which is associated with a reduced risk of acute GHVD | [77] |

| NLRP6 deficiency | NLRP6 deficiency in the intestinal epithelial cells leads downregulation of IL-18 and alters the AMP production to a profile that favors intestinal microbiota dysbiosis | [33] |

One of the first indications that the intestinal microbiota could play a role in transplant outcome came from the observation that transplanted germ-free mice had improved survival compared to specific-pathogen free mice with intact microbiota [6]. Since then, clinical strategies aimed at “decontaminating” the gut have been an area of active investigation, although these clinical trials have produced conflicting results, suggesting the need for mechanistic studies using preclinical models to fully identify important taxonomic groups and their interactions with the human host during allo-HCT [7]. Several clinical studies have reported associations between specific features of the intestinal microbiota and transplant outcomes, some favorable and some unfavorable [3, 8–13]. Many currently active clinical trials employ therapeutic strategies that aim to eliminate microbiome features associated with adverse transplant outcomes, while preserving features associated with desirable outcomes, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intestinal microbiota-focused clinical trials in allo-HCT patients

| Trial title | Phase | Aims and intervention | NCT number/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | |||

| Autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (Auto-FMT) for prophylaxis of Clostridium difficile infection in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | II | Assess the efficacy of auto-FMT for prevention of C. difficile infection in allo-HCT patients | NCT02269150 [37] |

| Oral supplementation of 2’-fucosyllactose in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients | I/II | 2’-fucosyllactose supplementation will lead to lower incidence of acute GVHD and blood-stream infection at day 100 post-allo-HCT | NCT04263597 |

| Oligosaccharide for Cdiff(+) heme-onc patients | Assess the feasibility of oligosaccharide supplementation (potato starch) in preventing C.

difficile colonization |

NCT03778606 | |

| GVHD | |||

| Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG in reducing incidence of graft-versus-host disease in patients who have undergone donor stem cell transplant | Assess the treatment of allo-HCT with a probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in reducing incidence of lower GI acute GVHD | NCT02144701 [78] | |

| Dietary manipulation of the microbiome-metabolomic axis for mitigating GVHD in allo HCT patients | II | Evaluate the feasibility, safety and efficacy of administering potatobased resistant starch to allo-HCT patients | NCT02763033 |

| Study of IL-22 IgG2-Fc (F-652) for subjects with grade II-IV lower GI aGVHD | I/II | Investigate the safety and pharmacokinetics of F-652 (in combination with corticosteroids) in allo-HCT patients with grade II-IV lower GI aGVHD | NCT02406651 |

| Prebiotic galacto-oligosaccharide and acute GVHD | Determine whether the prebiotic galacto-oligosaccharide can modulate the intestinal microbiota and help prevent GVHD | NCT04373057 | |

| Lipopolysaccharide metabolism and identification of potential biomarkers predictive of graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (MetAlloLip) | Assess whether LPS activity index can be quantified early after allo-HCT and predictive of the risk of severe GVHD | NCT03918343 | |

| Lactobaccilus Plantarum in preventing acute graft-versus-host diseae in children undergoing donor stem cell transplant | III | Assess the efficacy of orallyadministered Lactobacillus plantarum in preventing the development of GI acute GHVD | NCT03057054 |

| Fructooligosacharides in treating patients with blood cancer undergoing donor stem cell transplant | I | Evaluate the side effects and optimal dose of prebiotic fructooligosaccharides in the prevention of acute GVHD | NCT02805075 |

| Individualized nutrition for adult recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplantations - effects on quality of life (NASQ) | Assess the effect of lactose-reduced and energy-enriched oral nutrition on acute GVHD incidence, engraftment time and neutropenic fever | NCT01181076 | |

| Human lysozyme goat milk for the prevention of graft versus host disease in patients with blood cancer undergoing a donor stem cell transplant | Assess the feasibility, toxicity and efficacy of human lysozyme goat milk in the prevention of GVHD | NCT04177004 | |

| Immune reconstitution | |||

| Dysbiosis and immune reconstitution after allo-HSCT (PARI-DYS) | Explore the changes in the intestinal microbiota and early post-transplant reconstitution of invariant NKT cells | NCT03616015 | |

| Monitoring of immune and microbial reconstitution in (HCT) and novel immunotherapies | Correlate microbiota changes and their interactions with immune reconstitution and immune functions after allo-HCT | NCT03557749 | |

| Strategies to manipulate the gut microbiota during allo-HCT | |||

| Aims and intervention | NCT number/ References | ||

| Fecal microbiota transplantation in restoring the intestinal microbiota health and in preventing infections and acute high-risk GVHD during allo-HCT | NCT03720392; NCT04014413; NCT03359980; NCT03678493; NCT04139577; NCT03549676; NCT04059757; NCT03812705; NCT04285424; NCT04280471; NCT03819803; NCT04269850 | ||

| Optimizing antibiotics treatment to minimize intestinal microbiota damage, prevent subsequent infections and GVHD during allo-HCT | NCT03733340; NCT03078010; NCT03727113; NCT02641236 | ||

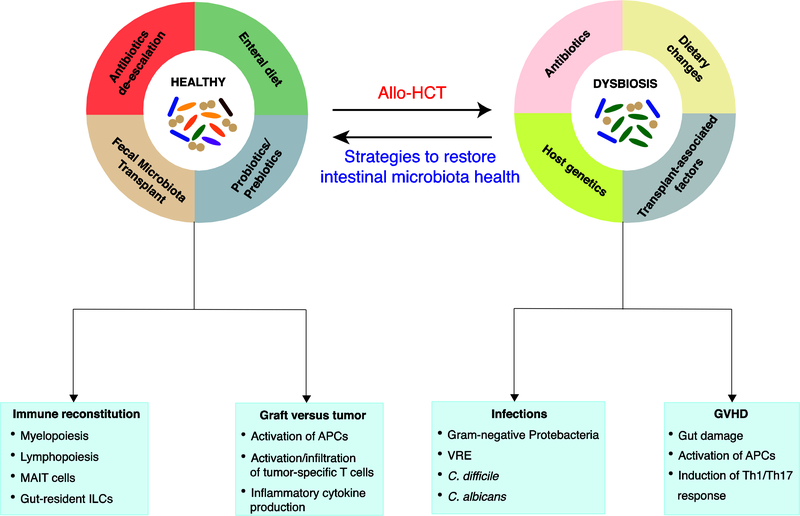

This review outlines our current understanding of the role of the intestinal microbiota in allo-HCT, focusing on four important clinical outcomes: infection, immune reconstitution, GVHD and relapse (Fig. 1). Allo-HCT patients are at an increased risk of infection due to high degree of immunosuppression and prolonged hospital admissions, and several studies have suggested that the intestinal commensals play a role in preventing intestinal domination by both opportunistic pathogens and commensal bacteria, which can lead to subsequent blood-stream infections [14–16]. Acute GVHD (aGVHD) is a systemic, potentially fatal condition that occurs following allo-HCT, in which donor-derived T cells recognize host antigens as foreign, resulting in cytotoxic tissue damage to predominantly the skin, the liver and the gastrointestinal tract [17]. Reconstitution of the immune system is critical for the recovery of transplant patients, and aberrant immune reconstitution can lead to increased late infections, increased GVHD incidences and failure of graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect [18]. Lastly, the GVT effect following allo-HCT, in which graft-derived T cells and NK cells eliminate host malignant cells, is critical in ensuring long-term survival in allo-HCT patients.

Figure 1. Intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and patient outcomes following allo-HCT.

Allo-HCT patients are exposed to various environmental conditions including cytotoxic conditioning regimens, antibiotics, and dietary changes that might contribute to changes in the intestinal microbiota. These injuries to the intestinal microbiota, in turn, are associated with transplant outcomes such as infections, immune reconstitution, GVHD and relapse through various different immunological mechanisms involving different hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cell populations. Strategies to restore the intestinal microbiota health include fecal microbiota transplantation, de-escalated antibiotic exposures and enteral diets that promote the growth of beneficial bacteria. VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; MAIT, mucosal-associated invariant T cell; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; APC, antigen-presenting cell; Th, T helper.

How does the intestinal microbiome interact with the mammalian host?

The intestinal bacterial community consists of over 2000 species, the majority of which belong to phyla Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes [19, 20]. Gut bacterial communities are highly variable in healthy people, but are thought to remain relatively stable within individuals over time. In healthy adults, the inter-personal variations in the gut bacterial community structure can be partially, though not entirely, explained by variation in diet [21–23].

The majority of studies of the role of the intestinal microbiota in allo-HCT outcome have utilized 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, which relies on pre-amplification of the hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene prior to sequencing. This technique allows identification of the intestinal microbiota at genus-level resolution, and is practical to scale to a large collection of fecal samples. The disadvantage of 16S amplicon sequencing, however, is the lack of taxonomic resolution at species and strain-specific levels [24]. To address this challenge, whole-genome metagenomic sequencing can be performed, which provides the genomes of all micro-organisms present in fecal samples, resulting in high-resolution profiles of the intestinal bacterial compositions and predictions of functional potential of these micro-organisms [25–27]. In addition, advances in metabolomics have allowed further assessment of the function of intestinal bacteria by measuring actual metabolites produced by the gut microbes. Together, sequencing and metabolomic analyses of clinical samples can generate high-quality hypotheses to be tested in pre-clinical mechanistic models of human health and disease [20, 28, 29].

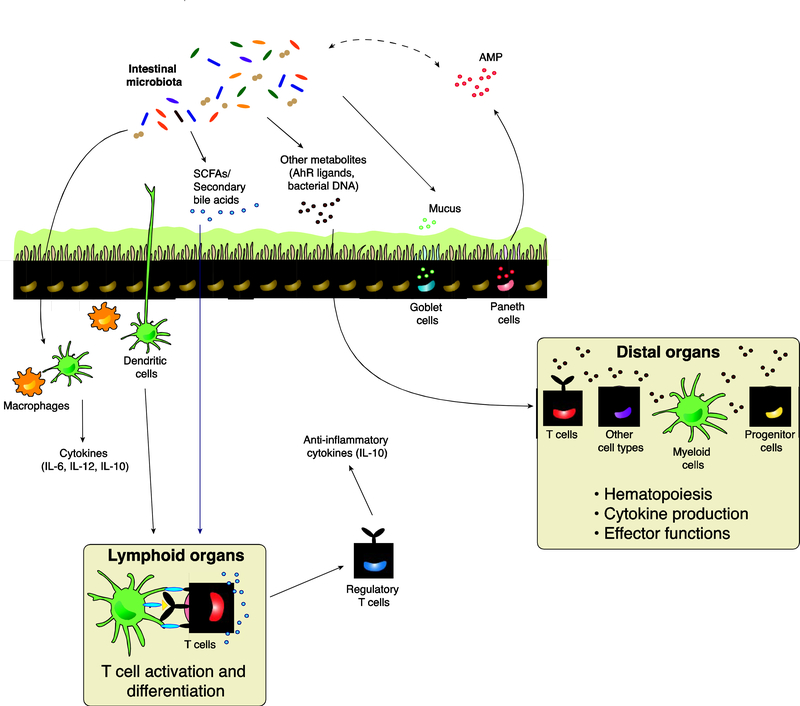

The gut commensals can influence local and systemic immunity through both direct interactions with immune cells, and indirect interactions mediated via secreted microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), secondary bile acids and other small molecules (summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2) [30]. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate and acetate, are produced as a result of the fermentation of dietary fiber by the intestinal microbiota. Butyrate (and to a lesser extent propionate) acts as a histone deacetylase inhibitor to promote the differentiation of colonic FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) in mice [31, 32]. Propionate and acetate also induce anti-inflammatory responses and improve intestinal epithelial barrier integrity [33, 34]. Secondary bile acids, which are produced as a result of microbial metabolism of primary bile acids excreted by the liver, can also induce differentiation of peripheral Tregs [35, 36]. Microbe-derived indole derivatives from tryptophan metabolism confer a protective effect against epithelial barrier damage after total body irradiation (TBI) and in a chemically-induced colitis model [37, 38]. Moreover, the intestinal microbiota also produces many metabolites that act as ligands for the aryl hydrocarbon receptors (AhR), which are expressed by many cell types, and can play an important role in the induction and development of immune-mediated diseases (Fig. 2) [39–41].

Figure 2. Interactions between the intestinal microbiota and the mammalian host.

Within the gut lumen and intestinal epithelial environment, the intestinal microbiota promotes mucus production from goblet cells, as well as antimicrobial peptides production from Paneth cells to maintain gut homeostasis. Antimicrobial peptides, in turn, regulate the intestinal microbial compositions. Signals from the intestinal microbiota also activate antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, leading to downstream production of cytokines that promote context-specific inflammation or tolerance. Dendritic cells can also migrate to lymphoid organs to present antigens and activate T cells, and microbially derived metabolites such as SCFAs and secondary bile acids could mediate this process by influencing T cell activation and differentiation. Other microbially derived products such as AhR ligands, bacterial DNA and bacterial components can also translocate across the intestinal epithelial barrier into systemic circulation, reaching distal organs such as the liver, the lung and the bone marrow and modulate the generation, activation and differentiation of different cell subsets at these sites. SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; AhR, aryl-hydrocarbon receptor; AMP, anti-microbial peptide; IL, interleukin.

The intestinal microbiota contributes to the maintenance and degradation of the mucus layer in the GI tract, which forms a protective barrier between microbes and intestinal epithelial cells (IECs). However, the outgrowth of bacteria with mucus-degrading activities can potentially lead to impaired intestinal barrier integrity in mice [42–44]. In addition, the intestinal microbiota also modulates antimicrobial peptide (AMP) production by intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), such that disruption of the indigenous microbiota can affect AMP expression to favor the expansion of pathogenic bacteria in mice (Fig. 2) [45]. Alternatively, host genetics can also modulate the intestinal microbiota compositions: NLRP6 deficiency in mice leads to aberrant AMP production that favors intestinal microbiota dysbiosis (Table 1) [45]. Gut commensals can also directly induce the expression of critical innate immune effectors and AMPs to maintain intestinal mucosal integrity and prevent colonization by opportunistic pathogens [46, 47]. The intestinal commensals, by themselves, also confer colonization resistance against opportunistic pathogens by nutrient limitation and bacteriocins [14, 48, 49].

The intestinal microbiota and infections after allo-HCT

Clinical evidence

Infections account for about 30% of deaths within the first 100 days after allo-HCT [1]. During allo-HCT, intestinal microbiota diversity rapidly declines, commonly accompanied by domination of a single bacterial taxon such as members of the Enterococcus and Streptococcus genera, and members of the class Proteobacteria [5, 10]. Domination of the intestinal flora by organisms in the class Proteobacteria, as well as by organisms in the genus Enterococcus such as vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), commonly precedes, and is predictive of subsequent bacterial blood-stream infections by Gram-negative bacteria and VRE bacteremia, respectively [4, 50]. Exposure to fluoroquinolone prophylaxis was associated with a decreased risk of intestinal domination by Proteobacteria, as well as a decreased risk of Gram-negative infection in a multivariate analysis controlled for graft source, underlying disease and other antibiotic prophylactic regimens (Table 1) [4, 10].

Given the now well-established decline in microbiota diversity following allo-HCT and its association with poor transplant outcomes, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) represents a potentially efficacious intervention to restore the intestinal microbiota health following allo-HCT [3, 5, 11, 12, 51]. While the efficacy and safety of FMT remains under investigation, this procedure has proved to be effective to treat recurrent C. difficile infection (CDI) [51, 52]. Higher relative abundance of three specific bacterial families, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococceae and Bacteroidaceae, is associated with a reduced risk of CDI in allo-HCT patients [53]. These bacteria are some of the most abundant families in the intestinal microbiota of healthy people.

A recent clinical study described an association between the intestinal microbiota and fungal infection with Candida spp. during allo-HCT. Specifically, a decrease of total bacterial biomass and biodiversity, as well as loss of Lachnospiraceae and Bacteroidetes, is associated with increased relative abundance of Candida spp [54]. Increased intestinal abundance of butyrate producers, such as Clostridiales and Faecalibacterium, has been associated with a decreased risk of lower respiratory tract infection in allo-HCT patients [55].

Preclinical evidence

There are few preclinical studies focusing on the mechanisms by which the intestinal microbiota influences infections following allo-HCT. Microbe-derived metabolites and small molecules such as SCFAs, secondary bile acids and bactericidal toxins can directly inhibit the growth and colonization of opportunistic pathogens such C. albicans and VRE [14, 46, 56, 57]. However, it is necessary to validate these findings in the specific context of allo-HCT in order to develop appropriate microbiome-targeted interventions.

Intestinal microbiota and immune reconstitution post-allo-HCT

Clinical evidence

The influence of the intestinal microbiota on immune reconstitution in allo-HCT patients is an important and active area of research in the transplant field; however, thus far there are limited clinical data available. In a high-resolution computational analysis combining longitudinal data of total white blood cell count and fecal 16S sequencing from 2,047 allo-HCT patients, Bacteroidaceae, Prevotellaceae and Ruminococcaceae were associated with increased lymphocyte, monocyte and neutrophil counts, respectively [58]. Furthermore, high intestinal microbial biodiversity, high abundance of Blautia and Bacteroidetes, as well as high relative abundance of genes associated with the riboflavin synthesis pathway, have been associated with increased numbers of mucosal-associated variant T (MAIT) cells following allo-HCT in patients, although these findings need to be interpreted with caution due to small sample sizes [59, 60].

Preclinical evidence

Depletion of the intestinal microbiota with broad-spectrum antibiotics leads to impaired recovery of lymphocytes and neutrophils after total body irradiation (TBI) in mice, an effect which was able to be restored with caloric supplementation. Specifically, treatment of transplanted mice with sucrose supplementation did not significantly alter the total fecal bacterial abundance or the compositions of the gut flora, suggesting that the intestinal microbiota potentially provides additional nutrition from the diet to support early immune reconstitution [61]. At steady state, antibiotic-treated mice show significant bone marrow suppression and reduced peripheral lymphocyte counts, potentially an effect mediated via STAT1 signaling in progenitor cells [62], however, these findings have yet to be examined in the setting of allo-HCT.

Intestinal microbiota and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

Clinical evidence

Several studies have reported that increased microbial diversity during the peri-neutrophil engraftment period is associated with a decreased risk of GVHD-related mortality [3, 5, 11–13]. The intestinal microbial diversity during allo-HCT is most commonly determined through 16S sequencing of fecal samples that identify unique bacterial taxa and their relative abundance. Indoxyl sulfate, a product of the tryptophan metabolism by the intestinal microbiota, is a potential biomarker of intestinal biodiversity which can be measured in urine and which has been studied in a pilot study of 31 allo-HCT patients [11]. Decreased concentrations of these indole-derived metabolites were observed in allo-HCT patients with active aGVHD compared to patients without aGVHD [63].

Several specific members of the intestinal microbial community have been associated with either increased or decreased rates of GVHD. SCFA-producing members of the families Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, such as Blautia, Clostridium and Lachnoclostridium, are associated with protection against aGVHD-related mortality and chronic GVHD development [8, 64]. The absence of these beneficial bacteria attributed to broad-spectrum antibiotics is correlated with an increased risk of GVHD development, specifically in the GI tract [65, 66]. High relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae has also been correlated with an increased ratio of Treg/Th17 cells, potentially maintaining the balance of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory responses during GVHD [65, 67].

In addition, some bacterial taxa have been associated with increased GVHD severity. Enterococcus domination post-allo-HCT is associated with an increased risk of severe GVHD and GVHD-related mortality in allo-HCT patients, as well as in mice [11, 68]. Furthermore, Enterococcus requires lactose as a source of nutrition for maximal growth, and patients with the single-nucleotide polymorphism associated with lactose intolerance (thus retention of lactose in the gut lumen) also saw an increased risk of Enterococcus domination following allo-HCT [68]. Akkermansia expansion, which is associated with exposures to piperacillin/tazobactam and imipenem during transplant, is also correlated with an increased risk of GVHD-related mortality in both humans and mice [42, 69]. Moreover, this genus has been associated with an increased risk of chronic GVHD [64].

Preclinical evidence

The intestinal microbiota potentially makes a mechanistic contribution to the development of GVHD through multiple mechanisms. Tissue damage caused by conditioning regimens allow translocation of pathogen-associated molecular patterns such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) across the intestinal barrier, which can activate the innate immune system and is thought to be key for initiation of GVHD [70, 71]. Exposure to imipenem leads to decreased gut barrier integrity, resulting in more severe GVHD in mice, potentially due to the resultant increase in relative abundance of Akkermansia [69]. Treatment with indole-3-carboxaldehyde, an indole derivative, limits gut epithelial damage and prevents the initial cascade of inflammatory responses triggered by TBI in a mouse model of GVHD [37]. Other indole derivatives can also activate AhR on innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) and induce IL-22 expression, which promotes epithelial regeneration after radiation and improves GVHD survival in mice [39, 40, 72].

In addition, propionate, and to a lesser extent butyrate, has been shown to promote the activation of the NLPR3 inflammasome to support intestinal crypt regeneration post-allo-HCT [73]. Oral dosing of mice with 17 butyrate-producing Clostridium strains after allo-HCT restores the intestinal butyrate levels and improves intestinal epithelial integrity, thereby reducing GVHD severity [74]. Oral administration of butyrate in a mouse model of allo-HCT also promotes epithelial cell regeneration and mitigates GVHD [74].

Bacteria signal through toll-like receptors to recruit neutrophils into the ileum after allo-HCT, where they generate reactive oxygen species that further amplify radiation-induced damages in the GI tract of recipient mice [75]. Moreover, neutrophil migration from the ileum to the mesenteric lymph nodes also depends on the intestinal microbiota, promoting alloantigen presentation to donor T cells [76]. The intestinal microbiota also promotes MHC class II expression on IECs in a MyD88/TRIF-dependent manner, following the cues of inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12, thereby increasing alloantigen presentation to donor T cells [77]. Furthermore, professional donor-derived APCs such as CD103+ DCs migrate from the lamina propria to the mesenteric lymph nodes, where they promote the activation and proliferation of donor T cells through antigen presentation, and release inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-12 in a MyD88/TRIF-dependent manner, suggesting the involvement of the intestinal microbiota in the activation and migration of APCs in GVHD pathophysiology [78]. Pre-transplant Enterococcus colonization led to increased GVHD severity and mortality in a germ-free mouse model of GVHD and furthermore, feeding experimental mice a lactose-free diet prevented Enterococcus growth while preserving other members of the gut commensals, leading to improvement in GVHD-related survival in a mouse model of allo-HCT [68]. The specific mechanism by which Enterococcus modulates post-transplant immune function and influences alloreactive T cells during GVHD remains unclear and requires further investigation [68].

Not unsurprisingly, the influence of the complex bacterial community in the GI tract on GVHD outcome is complex, with some bacterial taxa appearing to be protective and others pathogenic. This highlights the need for novel therapeutic approaches which enhance the protective taxa while eliminating or decreasing the pathogenic taxa.

Intestinal microbiota and graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect

Clinical evidence

Relapse and/or progression of disease remains the most common cause of death in allo-HCT patients, accounting for 51–59% of mortality at or after day 100 post-transplant [1]. Features of the intestinal microbiota might serve as a potential biomarker of relapse following allo-HCT [31, 35, 79, 80]. In the context of allo-HCT, a cluster of bacteria including Eubacterium limosum has been associated with a decreased risk of relapse in a multivariate analysis of 541 patients from MSKCC, where the analysis was controlled for graft source, conditioning intensity, HLA-match and disease [9]. E. limosum is a producer of butyrate, propionate, acetate and lactate, and has previously been demonstrated to attenuate the severity of chemically induced colitis [81]. Whether this particular species may influence GVT responses after allo-HCT remains unclear and should be explored further.

Preclinical evidence

Several studies using mouse models have suggested that the intestinal microbiota might influence antitumor activities of immunotherapies outside the context of allo-HCT [82–85]. It is necessary to follow up on the finding regarding the influence of E. limosum on the graft-versus-tumor effects with a mechanistic study using mouse models of allo-HCT, as well as exploring the role of other bacterial taxa in the antitumor activities in the setting of allo-HCT.

Therapeutic interventions

There are currently a number of clinical trials underway that target the intestinal microbiota in the allo-HCT patient population (summarized in Table 1). Multiple clinical trials are exploring the safety and efficacy of pre- and post-transplant FMT in the prevention of C. difficile and other infections in allo-HCT patients, as well as exploring microbiome-targeted strategies for prevention and treatment of steroid-refractory acute GVHD. Optimization of antibiotic regimens to limit the damage to the gut flora is also being actively investigated in the clinic. While previous studies indicate that the intestinal microbiota states during the pre-transplant and peri-neutrophil-engraftment periods can predict patient outcomes, the timeframe in which microbiome-targeted therapies may provide maximal benefits requires further investigations in clinical trials [3]. Additionally, multi-omic approaches, incorporating metagenomics and metabolomics in the context of well-designed clinical trials will further expound on the potential mechanisms by which the intestinal microbiota influences allo-HCT outcomes.

Conclusion

Clinical investigations have described relationships between the intestinal microbiota during allo-HCT and multiple patient outcomes, most notably GVHD and infection, but also immune reconstitution and GVT. Preclinical studies have furthered these clinical findings by elucidating some key mechanisms, most importantly the activation and increased antigen-presenting functions of APCs, effector functions of T cells and key mediated cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-12. However, knowledge gaps persist that could potentially limit the clinical application of microbiota-modulating therapies. Specifically, it is unclear whether the intestinal microbiota needs direct contact with immune cells to exert effects, or whether these interactions are mediated through microbially derived metabolites which can be potentially neutralized with inhibitors. Furthermore, the critical time points in which the intestinal microbiota exerts its influence on outcomes in allo-HCT remain unclear, and this is critical data that is required to determine the time window for clinical interventions. The future of microbiota research in the context of allo-HCT will combine the insights of clinical and preclinical studies, and translating these observational and mechanistic understandings into clinical trials will be key to developing microbiome-targeted strategies to maximize patient outcomes following allo-HCT.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest

Dr. van den Brink reports grants from NCI: P01 CA023766-40, grants from NCI: P30 CA008748-54, grants from NCI: R01 CA228308-03, grants from NIAID: U01 AI124275-05, grants from Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, Co-Director, grants, personal fees and other from Seres Therapeutics, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Merck & Co, Inc., personal fees from Acute Leukemia Forum, personal fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Therakos, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from PureTech, personal fees from Straximm, personal fees from Rubius Therapeutics, personal fees and other from DKMS, personal fees from Magenta Therapeutics, personal fees from WindMIL Therapeutics, grants from NIA: P01 AG052359-04, grants from NHLBI: R01 HL123340-06, grants from NHLBI: R01 HL125571-05, grants from NCI: R01 CA228358-03, grants from Tri-Institutional Stem Cell Initiative award 2016-13, grants from The Lymphoma Foundation, grants from The Susan and Peter Solomon Divisional Genomics Program, personal fees from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Kite Pharma, Inc., grants from NHLBI: R01 HL147584-02, grants from Cycle for Survival, grants from Starr Cancer Consortium, grants from Hyundai Hope on Wheels, grants from Tri-Institutional Stem Cell Initiative, outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. van den Brink has a patent Intestinal Blautia and reduced GVHD-related Mortality with royalties paid to Seres Therapeutics, a patent Methods And Compositions For Detecting Risk Of Cancer Relapse with royalties paid to Seres Therapeutics, and a patent Bacterial Compositions and Methods for Cancer Survival pending. Dr. van den Brink has stock options with Seres Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.D’ Souza A FC, Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT): CIBMTR Summary Slides. 2019.

- 2.Ying Taur RRJ, Miguel-Angel Perales, et al. , The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood, 2014. 124(7): p. 1174–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peled JU, et al. , Microbiota as Predictor of Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382(9): p. 822–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoma I, et al. , Compositional flux within the intestinal microbiota and risk for bloodstream infection with gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taur Y, et al. , The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood, 2014. 124(7): p. 1174–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Bekkum DW, et al. , Mitigation of secondary disease of allogeneic mouse radiation chimeras by modification of the intestinal microflora. J Natl Cancer Inst, 1974. 52(2): p. 401–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fredricks DN, The gut microbiota and graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest, 2019. 129(5): p. 1808–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenq RR, et al. , Intestinal Blautia Is Associated with Reduced Death from Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2015. 21(8): p. 1373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peled JU, et al. , Intestinal Microbiota and Relapse After Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. J Clin Oncol, 2017. 35(15): p. 1650–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taur Y, et al. , Intestinal domination and the risk of bacteremia in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis, 2012. 55(7): p. 905–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holler E, et al. , Metagenomic analysis of the stool microbiome in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplantation: loss of diversity is associated with use of systemic antibiotics and more pronounced in gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2014. 20(5): p. 640–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golob JL, et al. , Stool Microbiota at Neutrophil Recovery Is Predictive for Severe Acute Graft vs Host Disease After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Clin Infect Dis, 2017. 65(12): p. 1984–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simms-Waldrip TR, et al. , Antibiotic-Induced Depletion of Anti-inflammatory Clostridia Is Associated with the Development of Graft-versus-Host Disease in Pediatric Stem Cell Transplantation Patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2017. 23(5): p. 820–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SG, et al. , Microbiota-derived lantibiotic restores resistance against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Nature, 2019. 572(7771): p. 665–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leslie JL, et al. , The Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Clearance of Clostridium difficile Infection Independent of Adaptive Immunity. mSphere, 2019. 4(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen J, Lindner C, and Hakki M, Incidence and Outcomes of Bacterial Bloodstream Infections during Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Involving the Gastrointestinal Tract after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2019. 25(8): p. 1648–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrara JL, Levy R, and Chao NJ, Pathophysiologic mechanisms of acute graft-vs.-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 1999. 5(6): p. 347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Brink MR, Velardi E, and Perales MA, Immune reconstitution following stem cell transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2015. 2015: p. 215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, et al. , An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nat Biotechnol, 2014. 32(8): p. 834–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poyet M, et al. , A library of human gut bacterial isolates paired with longitudinal multiomics data enables mechanistic microbiome research. Nat Med, 2019. 25(9): p. 1442–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costello EK, et al. , Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science, 2009. 326(5960): p. 1694–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.David LA, et al. , Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature, 2014. 505(7484): p. 559–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson AJ, et al. , Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans. Cell Host Microbe, 2019. 25(6): p. 789–802 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janda JM and Abbott SL, 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification in the diagnostic laboratory: pluses, perils, and pitfalls. J Clin Microbiol, 2007. 45(9): p. 2761–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang X, et al. , Metagenomics-Based, Strain-Level Analysis of Escherichia coli From a Time-Series of Microbiome Samples From a Crohn’s Disease Patient. Front Microbiol, 2018. 9: p. 2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vatanen T, et al. , The human gut microbiome in early-onset type 1 diabetes from the TEDDY study. Nature, 2018. 562(7728): p. 589–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin J, et al. , A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature, 2012. 490(7418): p. 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lloyd-Price J, et al. , Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature, 2019. 569(7758): p. 655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zierer J, et al. , The fecal metabolome as a functional readout of the gut microbiome. Nat Genet, 2018. 50(6): p. 790–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belkaid Y and Harrison OJ, Homeostatic Immunity and the Microbiota. Immunity, 2017. 46(4): p. 562–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furusawa Y, et al. , Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature, 2013. 504(7480): p. 446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arpaia N, et al. , Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature, 2013. 504(7480): p. 451–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda S, et al. , Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature, 2011. 469(7331): p. 543–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trompette A, et al. , Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med, 2014. 20(2): p. 159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hang S, et al. , Bile acid metabolites control TH17 and Treg cell differentiation. Nature, 2019. 576(7785): p. 143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell C, et al. , Bacterial metabolism of bile acids promotes generation of peripheral regulatory T cells. Nature, 2020. 10.1038/s41586-020-2193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swimm A, et al. , Indoles derived from intestinal microbiota act via type I interferon signaling to limit graft-versus-host disease. Blood, 2018. 132(23): p. 2506–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimada Y, et al. , Commensal bacteria-dependent indole production enhances epithelial barrier function in the colon. PLoS One, 2013. 8(11): p. e80604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zelante T, et al. , Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity, 2013. 39(2): p. 372–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JS, et al. , AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat Immunol, 2011. 13(2): p. 144–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manfredo Vieira S, et al. , Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science, 2018. 359(6380): p. 1156–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desai MS, et al. , A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell, 2016. 167(5): p. 1339–1353 e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schroeder BO, et al. , Bifidobacteria or Fiber Protects against Diet-Induced Microbiota-Mediated Colonic Mucus Deterioration. Cell Host Microbe, 2018. 23(1): p. 27–40 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sovran B, et al. , Age-associated Impairment of the Mucus Barrier Function is Associated with Profound Changes in Microbiota and Immunity. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levy M, et al. , Microbiota-Modulated Metabolites Shape the Intestinal Microenvironment by Regulating NLRP6 Inflammasome Signaling. Cell, 2015. 163(6): p. 1428–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fan D, et al. , Activation of HIF-1alpha and LL-37 by commensal bacteria inhibits Candida albicans colonization. Nat Med, 2015. 21(7): p. 808–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cash HL, et al. , Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science, 2006. 313(5790): p. 1126–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sorbara MT and Pamer EG, Interbacterial mechanisms of colonization resistance and the strategies pathogens use to overcome them. Mucosal Immunol, 2019. 12(1): p. 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rogers LA, The Inhibiting Effect of Streptococcus Lactis on Lactobacillus Bulgaricus. J Bacteriol, 1928. 16(5): p. 321–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ford CD, et al. , Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus Colonization and Bacteremia and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2017. 23(2): p. 340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taur Y, et al. , Reconstitution of the gut microbiota of antibiotic-treated patients by autologous fecal microbiota transplant. Sci Transl Med, 2018. 10(460). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hui W, et al. , Fecal microbiota transplantation for treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection: An updated randomized controlled trial meta-analysis. PLoS One, 2019. 14(1): p. e0210016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Lee YJ, et al. , Protective Factors in the Intestinal Microbiome Against Clostridium difficile Infection in Recipients of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. J Infect Dis, 2017. 215(7): p. 1117–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhai B, et al. , High-resolution mycobiota analysis reveals dynamic intestinal translocation preceding invasive candidiasis. Nat Med, 2020. 26(1): p. 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haak BW, et al. , Impact of gut colonization with butyrate-producing microbiota on respiratory viral infection following allo-HCT. Blood, 2018. 131(26): p. 2978–2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McKenney PT, et al. , Intestinal Bile Acids Induce a Morphotype Switch in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus that Facilitates Intestinal Colonization. Cell Host Microbe, 2019. 25(5): p. 695–705 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Britton RA and Young VB, Interaction between the intestinal microbiota and host in Clostridium difficile colonization resistance. Trends Microbiol, 2012. 20(7): p. 313–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schluter J, et al. , The gut microbiota influences circulatory immune cell dynamics in humans. bioRxiv, 2020. 10.1101/618256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhattacharyya A, et al. , Graft-Derived Reconstitution of Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2018. 24(2): p. 242–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Konuma T, et al. , Reconstitution of Circulating Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Its Association with the Riboflavin Synthetic Pathway of Gut Microbiota in Cord Blood Transplant Recipients. J Immunol, 2020. 204(6): p. 1462–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Staffas A, et al. , Nutritional Support from the Intestinal Microbiota Improves Hematopoietic Reconstitution after Bone Marrow Transplantation in Mice. Cell Host Microbe, 2018. 23(4): p. 447–457 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Josefsdottir KS, et al. , Antibiotics impair murine hematopoiesis by depleting the intestinal microbiota. Blood, 2017. 129(6): p. 729–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michonneau D, et al. , Metabolomics analysis of human acute graft-versus-host disease reveals changes in host and microbiota-derived metabolites. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Markey KA, et al. , Microbe-derived short chain fatty acids butyrate and propionate are associated with protection from chronic GVHD. Blood, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han L, et al. , Intestinal Microbiota at Engraftment Influence Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease via the Treg/Th17 Balance in Allo-HSCT Recipients. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee SE, et al. , Alteration of the Intestinal Microbiota by Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Use Correlates with the Occurrence of Intestinal Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2019. 25(10): p. 1933–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han L, et al. , Intestinal Microbiota Can Predict Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2019. 25(10): p. 1944–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stein-Thoeringer CK, et al. , Lactose drives Enterococcus expansion to promote graft-versus-host disease. Science, 2019. 366(6469): p. 1143–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shono Y, et al. , Increased GVHD-related mortality with broad-spectrum antibiotic use after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in human patients and mice. Sci Transl Med, 2016. 8(339): p. 339ra71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cooke KR, et al. , LPS antagonism reduces graft-versus-host disease and preserves graft-versus-leukemia activity after experimental bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Invest, 2001. 107(12): p. 1581–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao Y, et al. , TLR4 inactivation protects from graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cell Mol Immunol, 2013. 10(2): p. 165–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindemans CA, et al. , Interleukin-22 promotes intestinal-stem-cell-mediated epithelial regeneration. Nature, 2015. 528(7583): p. 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fujiwara H, et al. , Microbial metabolite sensor GPR43 controls severity of experimental GVHD. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mathewson ND, et al. , Gut microbiome-derived metabolites modulate intestinal epithelial cell damage and mitigate graft-versus-host disease. Nat Immunol, 2016. 17(5): p. 505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schwab L, et al. , Neutrophil granulocytes recruited upon translocation of intestinal bacteria enhance graft-versus-host disease via tissue damage. Nat Med, 2014. 20(6): p. 648–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hulsdunker J, et al. , Neutrophils provide cellular communication between ileum and mesenteric lymph nodes at graft-versus-host disease onset. Blood, 2018. 131(16): p. 1858–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koyama M, et al. , MHC Class II Antigen Presentation by the Intestinal Epithelium Initiates Graft-versus-Host Disease and Is Influenced by the Microbiota. Immunity, 2019. 51(5): p. 885–898 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koyama M, et al. , Donor colonic CD103+ dendritic cells determine the severity of acute graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med, 2015. 212(8): p. 1303–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Round JL and Mazmanian SK, Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(27): p. 12204–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ivanov II, et al. , Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell, 2009. 139(3): p. 485–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kanauchi O, et al. , Eubacterium limosum ameliorates experimental colitis and metabolite of microbe attenuates colonic inflammatory action with increase of mucosal integrity. World J Gastroenterol, 2006. 12(7): p. 1071–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Routy B, et al. , Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science, 2018. 359(6371): p. 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sivan A, et al. , Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science, 2015. 350(6264): p. 1084–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vetizou M, et al. , Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science, 2015. 350(6264): p. 1079–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gopalakrishnan V, et al. , Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science, 2018. 359(6371): p. 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]