Abstract

Hair products can contain hormonally active and carcinogenic compounds. Adolescence may be a period of enhanced susceptibility of the breast tissue to exposure to chemicals. We therefore evaluated associations between adolescent hair product use and breast cancer risk. Sister Study participants (ages 35–74 years) who had completed enrollment questionnaires (2003–2009) on use of hair dyes, straighteners/relaxers, and perms at ages 10–13 years (N=47,522) were included. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for associations between hair products and incident breast cancer (invasive cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ), with consideration of heterogeneity by menopausal status and race/ethnicity. Over an average of 10 years of follow-up, 3,380 cases were diagnosed. Frequent use of straighteners and perms was associated with a higher risk of premenopausal (HR=2.11, 95% CI 1.26–3.55 and HR=1.55, 95%CI: 0.96–2.53, respectively) but not postmenopausal breast cancer (HR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.76–1.30 and HR=1.09, 95% CI: 0.89–1.35, respectively). Permanent hair dye use during adolescence was uncommon (<3%) and not associated with breast cancer overall (HR=0.97, 95% CI: 0.78–1.20), though any permanent dye use was associated with a higher risk among Black women (HR=1.77, 95% CI: 1.01–3.11). Although frequency of use of perms (37% non-Hispanic white vs. 9% Black) and straighteners (3% non-Hispanic white vs 75% Black) varied by race/ethnicity, associations with breast cancer did not. Use of hair products, specifically perms and straighteners, during adolescence may be associated with a higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer, hair dye, straighteners, hair products, early life

Background

In the United States, breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed among women.1 Breast cancer prior to menopause tends to present at more advanced stages and has a less favorable prognosis compared to breast cancer diagnosed after menopause.2,3 Accumulating evidence suggests etiologic heterogeneity by menopausal status at diagnosis.4 Certain early life risk factors, such as birth weight5 and age at menarche,6 are more strongly related to premenopausal compared to postmenopausal breast cancer. Early life, including puberty, which is a period of rapid cell changes and growth in the breast, has been hypothesized to be a potential window of susceptibility for breast cancer.7

Use of hair products is extremely common and use often begins during childhood and adolescence.8,9 Hair products are a potential source of exposure to carcinogens and endocrine disruptors.10 Hair product use patterns vary substantially by race/ethnicity, with use of straighteners/relaxers being much more common in Black women compared to white women.11,12 The pattern of use of chemical hair products has been hypothesized to be a contributor to the higher body burden of endocrine disrupting compounds observed in non-Hispanic Black women compared to white women.13,14 Black women are more likely than white women to be diagnosed with breast cancer at earlier ages15 and with hormone receptor-negative tumor subtypes,16 both of which are associated with lower survival.3,17,18 Chemical hair products have been proposed to be one potential factor that may contribute to racial disparities in breast cancer.19,20

Research considering the risk of breast cancer associated with early life use of hair products in a racially and ethnically diverse population is limited. Previous epidemiologic research on hair products has largely been inconclusive, focusing primarily on the relationship between adult use of hair dye use and breast cancer risk, largely in populations that were not racially/ethnically diverse.21–26 In the Sister Study, we previously reported a positive association of permanent hair dye and straighteners with overall breast cancer risk focusing on use in the year prior to enrollment; associations for permanent dye were notably stronger in Black women.27

In this study, we have expanded on our previous study focused on adult hair product use by investigating the association between adolescent use of various types of hair products and incident breast cancer risk in a large, prospective cohort of women. We hypothesized that breast cancer risk would be highest for women who frequently used these hair products during adolescence and that associations would vary by timing of breast cancer (e.g. premenopausal vs. postmenopausal breast cancer) and by race/ethnicity.

Methods

Study Population.

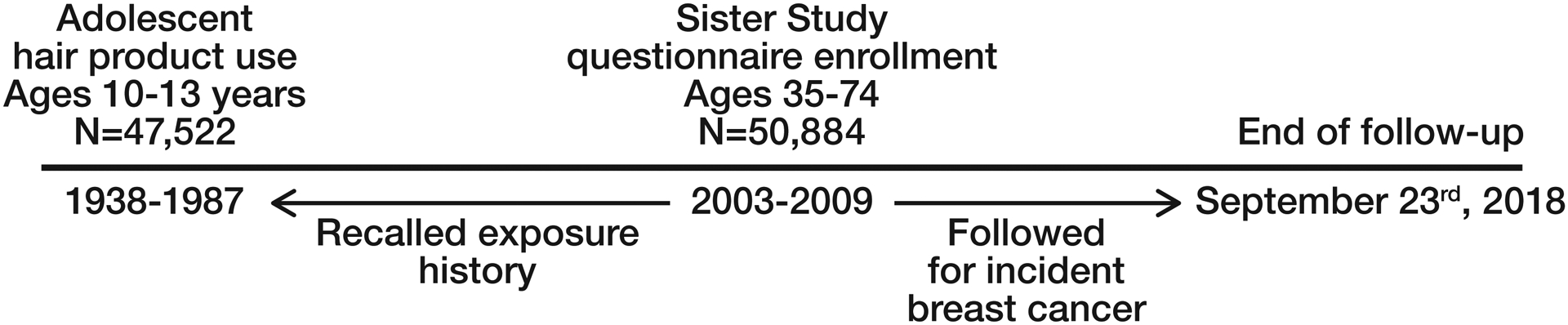

The prospective Sister Study cohort enrolled 50,884 women between 2003–2009 with the goal to evaluate environmental and lifestyle risk factors for incident breast cancer.28 Eligibility criteria included being between the ages of 35–74 years, living in the United States including Puerto Rico, and never having been diagnosed with breast cancer but having at least one full or half-sister who had been diagnosed with the disease. At the time of enrollment, study participants completed extensive structured questionnaires and computer-assisted telephone interviews, including questions on hair product use during adolescence. All participants had a home visit and a trained examiner measured height and weight. During study follow-up, participants complete annual health updates in addition to more detailed follow-up surveys every 2–3 years. Response rates have remained at approximately 90% throughout follow-up. This report includes follow up through September 23rd, 2018 (Data Release 8.0). A study timeline is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Outcome Assessment.

Breast cancer diagnoses are ascertained through self-report. Medical record and pathology reports are obtained in order to confirm the diagnosis and to get further information on the tumor including estrogen receptor (ER) status and staging. Medical records were available for over 82% of cases. When medical record data were not available, we used self-reported data. Agreement between self-reported and medical record obtained tumor characteristics has been high.29

Cases were defined as women who were diagnosed with either incident invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). We excluded women who were diagnosed with breast cancer before completing all enrollment activities or had an unknown age at breast cancer diagnosis (n=106) or contributed no follow-up time (n=314). We evaluated whether associations varied by menopausal status, ER status, and tumor extent (invasive vs. DCIS).

Exposure Assessment.

Adolescent use of hair products, assessed by questionnaire, was defined as frequency of use at ages 10–13 years. An early phase of the personal care product questionnaire differed in how adolescent hair product use was queried, asking about any use during “teen years” (not specific to ages 10–13 years), so women who completed that version were excluded (N=2,278). Women were asked about their frequency of personal use (defined as either self-application or application by another person) of several hair coloring products including permanent and semi-permanent dyes, temporary dyes and bleach. In the questionnaire, permanent dye was described as dye that shows your roots when the color grows out and semi-permanent dye was described as dye that fades in 6–8 weeks. Women were also asked about how often they “straightened or relaxed [their] hair or used pressing products” (referred to here as straighteners) and application of “hair permanents or body waves” (referred to here as perms). The response options included (1) did not use, (2) sometimes and (3) frequently. Due to low prevalence of hair coloring products, the response options for hair dyes were collapsed to did not use vs. ever used.

Covariate assessment.

Women reported self-identified race/ethnicity and were asked about sociodemographic characteristics of their household when they were around the age of 13 years, including educational attainment of family members and qualitative household income. Age at menarche and menopausal status were asked at enrollment and menopausal status and age at menopause were updated throughout follow-up.

Statistical Analysis.

We conducted a descriptive analysis evaluating participant characteristics by adolescent use of straighteners and perms. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for the association between adolescent hair product use and breast cancer risk. Age was the timescale of the Cox model, with women entering the model at age at baseline and being followed until breast cancer diagnosis or censoring event, which was defined as age of last follow-up or death. We tested for a linear trend for frequency of use with a chi-square test for the ordinal characterization of the variable for straightener and perm use. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using a likelihood ratio test and Schoenfeld residuals to compare models with and without interaction terms between each covariate and age with an α=0.05. There was no evidence of violations of the proportional hazard assumption.

The confounder adjustment set was identified using a directed acyclic graph. All models were adjusted for race (non-Hispanic white, Black, other), highest level of household educational attainment at age 13 years (< high school degree, high school degree or equivalent, some college/technical school, 4-year college degree or higher) and household income at age 13 years (well off, middle income, low income, poor). All women who self-identified as being Black, regardless of ethnicity, were classified as Black. We conducted a complete case analysis as missing data for the covariates (N=664) was <2%. The final sample size was N=47,522.

We considered whether associations varied by menopausal status by stratifying person-time based on menopausal status. For example, women became at risk for postmenopausal breast cancer at age at enrollment or age at menopause, whichever occurred later. Women who were premenopausal at enrollment were censored for premenopausal breast cancer at their age of menopause. To test for heterogeneity by menopausal status at diagnosis, menopause status was included as a time-varying term in the model. When considering whether hair product use was associated with ER+ breast cancer, women diagnosed with ER− were censored at the time of diagnosis. Similarly, when the outcome of interest was ER− breast cancer, women diagnosed with ER+ breast cancer were censored at the time of diagnosis. Heterogeneity in the associations by ER status was tested using joint Cox models, which is an approach used to compare exposure-disease associations across multiple disease subtypes.30

We estimated stratum-specific effect estimates for these associations among non-Hispanic white and Black women. Effect measure modification of the associations between hair products and breast cancer risk by race were evaluated by comparing models with and without cross-product terms using likelihood ratio tests. We did not estimate stratum-specific estimates for women who self-identified as other races/ethnicities (predominately Hispanic and Asian women) due to small sample size and limited power. We additionally estimated cumulative risk of premenopausal breast cancer by age 55 and assessed risk differences (RD) in the absolute risk among frequent versus never users of straighteners or perms using the Breslow method.31 There is evidence to suggest that early life use of hair products may be related to age at menarche,11 suggesting it may be a mediator rather than a confounder, which is why it was not included a priori in our adjustment set. However, to address the possibility of potential confounding by age at menarche, we conducted a sensitivity analysis including age at menarche in the adjustment set. As an additional sensitivity analysis, we explored associations for early life hair product use excluding women who were reported being users of that hair product in the 12 months prior to study baseline.

All analyses were completed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Adolescent use of hair dye was rare, with <3% of women reporting any use of either permanent or semi-permanent hair dye. In contrast, adolescent use of straighteners and hair perms was more common with approximately 10% of women reporting any use of straighteners and 34% of women reporting any hair perm use.

The frequency of use of straighteners and perms varied substantially by race/ethnicity (Table I). Black women were much more likely to use hair straighteners; 75% of Black women reported any straightener use during adolescence compared to 3% of white women. In contrast, 37% of white women and 9% of black women reported any perm use during adolescence. There was some suggestion of exposure trends by age at enrollment in the study, with older women more likely to report adolescent use of perms and women younger than 60 at enrollment more likely to report adolescent use of straighteners. Women with a household educational attainment of 4-year college degree or higher at age 13 were less likely to report being frequent users of both straighteners and perms compared to those with less household educational attainment. Study participant characteristics stratified by race/ethnicity and adolescent straightener and perm use are shown in Supplemental Table I.

Table I.

Study population characteristics at baseline by chemical straightener and perm use between the ages of 10–13 years, Sister Study, 2003–2009.

| Characteristics | Straightener Use | Perm use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not use | Sometimes used | Frequently used | Did not use | Sometimes used | Frequently used | ||

| (N = 41,799) | (N = 2,388) | (N = 2,168) | (N = 30,200) | (N = 13,993) | (N =1,350) | ||

| N (row %) | N (row %) | N (row %) | N (row %) | N (row %) | N (row %) | ||

| Age at baseline | |||||||

| ≤45 | 5,339 (88.8%) | 303 (5.0%) | 372 (6.2%) | 4,333 (72.6%) | 1,456 (24.4%) | 178 (3.0%) | |

| 46–50 | 6,221 (88.4%) | 413 (5.9%) | 403 (5.7%) | 5,901 (84.6%) | 1,004 (14.4%) | 74 (1.1%) | |

| 51–55 | 7,736 (86.1%) | 714 (7.9%) | 532 (5.9%) | 6,457 (72.9%) | 2,217 (25.0%) | 186 (2.1%) | |

| 56–60 | 8,172 (88.6%) | 569 (6.2%) | 478 (5.2%) | 5,406 (59.8%) | 3,320 (36.7%) | 319 (3.5%) | |

| 61–65 | 6,609 (93.0%) | 251 (3.5%) | 248 (3.5%) | 3,776 (54.4%) | 2,845 (41.0%) | 319 (4.6%) | |

| >65 | 7,722 (96.6%) | 138 (1.7%) | 135 (1.7%) | 4,327 (55.8%) | 3,151 (40.6%) | 274 (3.5%) | |

| Age at menarche, mean (SD) | 12.67 (1.51) | 12.5 (1.61) | 12.36 (1.64) | 12.66 (1.53) | 12.61 (1.5) | 12.53 (1.8) | |

| Race | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 37,543 (96.5%) | 1,192 (3.1%) | 158 (0.4%) | 23,879 (62.6%) | 13,033 (34.2%) | 1,209 (3.2%) | |

| Black | 976 (24.6%) | 1,013 (25.6%) | 1,975 (49.8%) | 3,627 (91.5%) | 252 (6.4%) | 85 (2.1%) | |

| Other | 3,280 (93.8%) | 183 (5.2%) | 35 (1%) | 2,694 (77.9%) | 708 (20.5%) | 56 (1.6%) | |

| Household education at age 13 years | |||||||

| <High school degree | 7,148 (84.4%) | 577 (6.8%) | 740 (8.7%) | 5,711 (68.7%) | 2,353 (28.3%) | 250 (3%) | |

| High school degree or equivalent | 14,969 (90.2%) | 845 (5.1%) | 782 (4.7%) | 10,414 (63.9%) | 5,315 (32.6%) | 577 (3.5%) | |

| Some college/technical school | 7,952 (91.2%) | 425 (4.9%) | 344 (3.9%) | 5,367 (62.9%) | 2,903 (34%) | 269 (3.2%) | |

| 4-year college degree or higher | 11,730 (93.3%) | 541 (4.3%) | 302 (2.4%) | 8,708 (70.3%) | 3,422 (27.6%) | 254 (2.1%) | |

| Household income at age 13 years | |||||||

| Well off | 2,738 (91.9%) | 162 (5.4%) | 80 (2.7%) | 2,131 (72.6%) | 722 (24.6%) | 83 (2.8%) | |

| Middle income | 25,577 (92%) | 1,300 (4.7%) | 915 (3.3%) | 17,939 (65.7%) | 8,569 (31.4%) | 781 (2.9%) | |

| Low income | 10,511 (87.8%) | 676 (5.6%) | 787 (6.6%) | 7,571 (64.4%) | 3,800 (32.3%) | 393 (3.3%) | |

| Poor | 2,973 (82.4%) | 250 (6.9%) | 386 (10.7%) | 2,559 (72%) | 902 (25.4%) | 93 (2.6%) | |

With an average of 10 years of follow-up, we identified 3,380 incident breast cancer cases. Hair coloring products were not associated with breast cancer risk overall or by menopausal status (Table II). Frequent use of both straighteners and perms were marginally associated with a higher breast cancer risk overall (HR=1.14 and HR=1.14, respectively). However, associations varied by menopausal status. Sometime (HR=1.37, 95% CI: 0.93–2.01) and frequent (HR=2.11, 95% CI: 1.26–3.55) use of straighteners were positively associated with premenopausal breast cancer (p-for-trend=0.004), but not postmenopausal breast cancer (sometimes used, HR=0.90, 95% CI: 0.73–1.10; frequently used, HR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.76–1.30) (p-for-heterogeneity= 0.02). When estimating the absolute risk difference, frequent straightener use was associated with an 11% (95% CI: 1%, 21%) higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer compared to never use. Similarly, frequent perm use was associated with a higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer (HR=1.55, 95% CI: 0.96–2.53), but to a lesser extent with postmenopausal breast cancer (HR=1.09, 95% C: 0.89–1.35) (p-for-heterogeneity=0.2). When estimating the absolute risk difference, frequent perm use was associated with a 6% (95% CI: −2%, 14%) higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer compared to never use. Findings for both straighteners and perms were essentially unchanged with further adjustment for age at menarche (data not shown). For both straighteners and perms, the positive association with premenopausal breast cancer remained in sensitivity analyses when we excluded those who used these products in the 12 months prior to enrollment (frequent straightener use, N=13 exposed cases, HR=2.07, 95% CI: 1.19–3.61; frequent perm use, N=14 exposed cases, HR=1.54, 95% CI: 0.90–2.63).

Table II.

Associations between hair product use between the ages of 10–13 years and breast cancer risk overall and by menopausal status, Sister Study 2003–2018.

| Overall Breast Cancer | Premenopausal Breast Cancer |

Postmenopausal Breast Cancer |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of hair product use between the ages of 10–13 years | Cases (N=3,380) | Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | Cases (N=573) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | Cases (N=2,807) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | p-valueb | ||

| Permanent dye use | ||||||||||

| None | 3,225 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 542 | 1.00 (referent) | 2,683 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Sometimes or frequently | 87 | 0.97 (0.78, 1.20) | 0.97 (0.78, 1.20) | 15 | 1.00 (0.60, 1.67) | 72 | 0.97 (0.77, 1.23) | 0.9 | ||

| Semi-permanent dye use | ||||||||||

| None | 3,242 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 546 | 1.00 (referent) | 2,696 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Sometimes or frequently | 64 | 0.87 (0.68, 1.11) | 0.87 (0.68, 1.12) | 12 | 0.93 (0.53, 1.65) | 52 | 0.86 (0.65, 1.13) | 0.8 | ||

| Temporary hair dye use | ||||||||||

| None | 3,225 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 549 | 1.00 (referent) | 2,676 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Sometimes or frequently | 80 | 0.87 (0.69, 1.08) | 0.87 (0.69, 1.08) | 7 | 0.77 (0.37, 1.63) | 73 | 0.88 (0.70, 1.11) | 0.7 | ||

| Bleach use | ||||||||||

| None | 3,173 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 534 | 1.00 (referent) | 2,639 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Sometimes or frequently | 135 | 1.01 (0.85, 1.20) | 1.01 (0.85, 1.20) | 23 | 0.87 (0.57, 1.32) | 112 | 1.04 (0.86, 1.26) | 0.4 | ||

| Straightener use | ||||||||||

| None | 3,024 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 491 | 1.00 (referent) | 2,533 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Sometimes | 148 | 0.94 (0.80, 1.12) | 0.97 (0.81, 1.16) | 32 | 1.37 (0.93, 2.01) | 116 | 0.90 (0.73, 1.10) | |||

| Frequently | 145 | 1.08 (0.91, 1.27) | 1.14 (0.90, 1.45) | 37 | 2.11 (1.26, 3.55) | 108 | 0.99 (0.76, 1.30) | |||

| p for trend | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.004 | 0.7 | 0.02 | |||||

| Permanent wave use (perm) | ||||||||||

| None | 2,069 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 434 | 1.00 (referent) | 1,635 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Sometimes | 1,069 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 102 | 0.92 (0.74, 1.14) | 967 | 1.06 (0.98, 1.15) | |||

| Frequently | 111 | 1.14 (0.94, 1.39) | 1.14 (0.94, 1.38) | 17 | 1.55 (0.96, 2.53) | 94 | 1.09 (0.89, 1.35) | |||

| p for trend | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |||||

adjusted for race, household education and income at age 13

p-for-heterogeneity from Wald test of a hair product by menopausal status (time-varying) interaction term

There was limited power to consider stratum-specific estimates for non-Hispanic white and Black women separately (Table III). Based on a small number of exposed cases (N=13), we observed a higher risk for breast cancer associated with permanent dye use among Black women (HR=1.77, 95% CI: 1.01–3.11) but not among white women (N= 70 exposed cases, HR=0.93, 95% CI: 0.74–1.18) (p for heterogeneity=0.06). Black women who reported using permanent hair dye during adolescence largely reported also using permanent hair dye in the 12 months prior to baseline (N=10 of 13 exposed cases) and so we could not reliably estimate the association of only using permanent hair dye during adolescence. The associations for hair straightener use and perm use did not vary appreciably by race (p-for heterogeneity=0.5 and p=0.6, respectively).

Table III.

Associations between hair product use between the ages of 10–13 years and breast cancer risk overall by race/ethnicity, Sister Study 2003–2018.

| Non-Hispanic White | Black | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of hair product use between the ages of 10–13 years | Cases (N=2,886) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | Cases (N=271) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

| Permanent dye use | ||||||

| None | 2,776 | 1.00 (referent) | 233 | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Sometimes or frequently | 70 | 0.93 (0.74, 1.18) | 13 | 1.77 (1.01, 3.11) | 0.06 | |

| Semi-permanent dye use | ||||||

| None | 2,782 | 1.00 (referent) | 243 | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Sometimes or frequently | 54 | 0.88 (0.67, 1.15) | 6 | 0.91 (0.40, 2.04) | 0.9 | |

| Temporary hair dye use | ||||||

| None | 2,765 | 1.00 (referent) | 241 | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Sometimes or frequently | 72 | 0.90 (0.71, 1.13) | 6 | 1.10 (0.49, 2.47) | 0.7 | |

| Bleach use | ||||||

| None | 2,713 | 1.00 (referent) | 245 | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Sometimes or frequently | 127 | 1.01 (0.85, 1.21) | 3 | NE | NE | |

| Straightener use | ||||||

| None | 2,753 | 1.00 (referent) | 64 | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Sometimes | 83 | 1.02 (0.82, 1.27) | 55 | 0.84 (0.59, 1.21) | ||

| Frequently | 14 | 1.37 (0.81, 2.31) | 128 | 1.04 (0.77, 1.40) | ||

| p for trend | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | |||

| Permanent wave use (perm) | ||||||

| None | 1,681 | 1.00 (referent) | 223 | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Sometimes | 1,005 | 1.04 (0.96, 1.13) | 18 | 1.36 (0.84, 2.20) | ||

| Frequently | 100 | 1.13 (0.93, 1.39) | 6 | 1.35 (0.60, 3.05) | 0.6 | |

| p for trend | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||

NE=Not estimated

adjusted for race, household education and income at age 13

p-for-heterogeneity from a likelihood test comparing models with and without interaction terms between the hair product and race

Frequent use of straighteners during adolescence appeared to be more strongly related to ER− breast cancer (HR=1.61, 95% CI: 0.88–2.96) compared to ER+ breast cancer (HR=1.08, 95% CI: 0.80–1.46), although the difference was not statistically significant (p-for-heterogeneity=0.5) (Supplemental Table II). With the exception of frequent perm use which appeared positively associated with invasive breast cancer (HR=1.24, 95% CI: 1.01–1.53) but inversely associated with DCIS (HR=0.72, 95% CI: 0.43–1.21), there were few differences by tumor extent (Supplemental Table III).

Discussion

In this large prospective cohort study of U.S. women, we found that frequent adolescent use of hair products that modify hair texture, specifically hair straighteners and perms, was associated with a higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer. Although based on a small number of cases, adolescent permanent hair dye use was also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer in Black women. This is the first study to examine the use of multiple hair products during adolescence in relation to breast cancer risk. These findings are important as the use of hair products to dye and modify hair texture is common and starts at young ages.8,9

It is biologically plausible that constituents in hair dye and other hair products may be relevant for breast cancer risk. Established carcinogens such as aromatic amines have been identified in hair dye and perm products.32–34 Interestingly, aromatic amine-DNA adducts associated with hair dye use were measured in breast milk epithelial cells; indicating that not only are these compounds circulating in the body and reaching the breast tissue, but they are also binding to DNA, which is a potential carcinogenic mechanism.32 Certain formulations of hair straighteners and relaxers have been found to include formaldehyde-releasing products when heated35 in addition to containing endocrine disrupting compounds such as phthalates, parabens and metals.10,36

We found evidence to support a role for hair straighteners and perms in the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, but not postmenopausal breast cancer. Other breast cancer risk factors, in particular obesity, have been shown to differ based on menopausal status at diagnosis.37,38 In our study of adult hair product use and breast cancer, associations did not vary by menopausal status,27 which supports that the finding observed here is not simply a reflection of continued use of these products in adulthood. It is plausible that adolescence may be a more relevant exposure window for premenopausal breast cancer risk than for breast cancer occurring after menopause. This is consistent with some prior research suggesting that breast cancer risk factors occurring during adolescence, such as age at menarche,6 may be more strongly related to premenopausal than postmenopausal breast cancer. It is also possible that the association observed here between adolescent use of hair products and premenopausal, but not postmenopausal, breast cancer could be due at least in part to the induction period of this specific exposure. Understanding the etiology of premenopausal breast cancer is critical as women diagnosed with breast cancer before menopause have worse prognosis compared to diagnoses after menopause3 and have other potential adverse health effects such as decreased fertility from cancer treatments.39

Hair straighteners/relaxers have been previously associated with breast cancer risk, including adult use of straighteners/relaxers in this study population. We previously observed that use of straighteners in the year prior to baseline was associated with an 18% higher risk of breast cancer overall and this association was stronger with increasing frequency of use.27 Other studies considering the risk associated with hair straighteners have been able to evaluate the risk associated with exposure during childhood or adolescence in addition to adult use. In the Women’s Circle of Health Study (WCHS), a case-control study of women in New York, use of relaxers before age 12 and between the ages of 13–19 years was positively, but imprecisely, associated with ER− breast cancer among African-American women;24 which is consistent with our finding of a suggestive higher risk for ER− tumors. In the Ghana Breast Health study, use of relaxers was associated with a higher risk overall and risk was elevated regardless of age of first use, including in the youngest age category (<21 years).40 In contrast, among women in the Black Women’s Health Study, age at first use of hair relaxers during childhood or adolescence (defined as < 10 years or 10–19 years) was not associated with breast cancer risk.41 The differences in findings across these study populations could be due to variability in behavioral patterns in terms of timing of exposure to various hair products across cohorts and study periods. Associated changes in formulations of straighteners/relaxers over time and by geographic location may also contribute to variation.

Hair coloring products, including permanent, semi-permanent and temporary dyes, were rarely used between the ages of 10–13 years in our cohort. Overall, there was little evidence to support that adolescent hair dye use was associated with breast cancer risk. We did not identify other studies that have specifically evaluated adolescent use of hair dyes in relation to breast cancer risk. The null association for adolescent hair dye use is largely consistent with previous studies of adult hair dye which have suggested that any hair dye-associated risks with overall breast cancer may be small.21–27,42 However, most, but not all, of these studies have been conducted in predominately white study populations; therefore, these findings may not be applicable to Black women.

In the current study, permanent hair dye use was associated with an imprecise, but elevated, breast cancer risk in Black women. This higher risk is consistent with our previous finding of a stronger association for adult use of permanent hair dye in Black women compared to non-Hispanic white women.27 Adult use of hair dye, in particular dark dyes, was associated with a higher risk of breast cancer among African-American women in WCHS.24 Most of the Black women who reported using permanent hair dye during adolescence in our study population also reported using permanent hair dye in the 12 months before study baseline and thus, we could not reliably estimate the risk due to adolescent use alone. In addition, this observed higher risk is based on a small number of exposed cases and requires caution and replication in other study populations that are well-powered to evaluate these associations in Black women.

This is a prospective cohort; women were asked to recall their exposures prior to any diagnosis of breast cancer which will eliminate recall bias. However, women were asked to consider hair product use many decades prior which would undoubtedly result in some measurement error and possible non-differential misclassification. Frequency of use response categories were broad (never, sometimes, frequently), which may minimize misclassification. Our observation that higher risks were largely limited to women who reported frequently using hair straighteners and perms suggests that we are correctly identifying those with the highest exposure. Although we adjusted our statistical models for race/ethnicity, household education and relative income during childhood, it is possible that residual confounding by other early life sociodemographic factors may play a role.

A strength of this study is that we were able to compare across a wide range of hair products including different types of hair dye in addition to straighteners and perms, which previous studies have not done. However, we did not have information on specific formulations or products that were used. Women in our cohort would have been between the ages of 10–13 years between 1939–1987 and thus the findings presented here represent exposure to products during this time. Although some of the main constituents of hair products appear to be relatively stable over time42,43, formulations have changed44 and would vary by brand. As such, we are unable to identify specific chemical constituents which may be contributing to risk. In this cohort, the frequency of use of hair dye use during adolescence was very low and therefore we were unable to conduct dose-response analyses, which may in part explain the lack of association observed overall if adolescent hair dye use does contribute to breast cancer risk. Adolescents today may be more likely to use hair dye products,9 and formulations may differ; this should be considered in future studies.

Consistent with prior studies, we observed that Black women are much more likely to use hair straighteners than white women and use starts at young ages.8,11 However, our questionnaire asked about combined use of hair straighteners, relaxers, or “pressing products” which refers to heat-based methods to straighten hair. This more temporary approach to straightening does not involve the use of chemical straighteners or relaxers, although some type of hair product may be used along with the heated comb or flatiron. Thus, some women classified as exposed may not have been truly exposed to the chemical products of interest suggesting that the magnitude of findings reported here may underestimate the true risk. Furthermore, this misclassification could be differential by race.

Despite having over 50,000 women in this study and ten years of follow-up time, adolescent exposure to hair products was rare and race-specific estimates were imprecise. We were also unable to jointly stratify by race and breast cancer characteristics such as menopausal status and ER tumor subtype. Given the higher prevalence of straightener use in Black women and the associations observed here between straightener use and premenopausal and ER− breast cancer, the potential contribution of chemical straighteners to racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer warrant further study.45 Future research may require pooling efforts to be adequately powered to address this research question in Black women with consideration of either tumor subtype or menopausal status. Finally, this study population includes women who all have a family history of breast cancer and thus, these results may not be generalizable to all women.

In this large prospective cohort, we found evidence to suggest that use of hair products during adolescence, in particular straighteners and perms, is a potential risk factor for premenopausal breast cancer. These findings are reflective of hair products that were on the market decades ago. More research is needed to understand the potential health impact of hair products that are currently being used, to evaluate how these products may contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer and to better understand which components within these products could increase breast cancer risk.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Impact:

Hair products including dye, straighteners and perms contain numerous chemicals which may play a role in cancer risk and are often used starting in adolescence. This study evaluated the relationship between use of hair dye, chemical straighteners and perms, during the ages of 10–13 years and later breast cancer risk in a large prospective cohort. Frequent use of straighteners and perms was associated with a higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer.

Source of Funding:

This work was funded in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Z1A ES-103332 (AJW), Z1A ES103325 (CLJ), Z01 ES044005 (DPS)

Abbreviations:

- 95% CIs

95% confidence interval

- DCIS

ductal carcinoma in situ

- ER

estrogen receptor

- HR

hazard ratio

- NE

not estimated

- RD

risk differences

- WCHS

Women’s Circle of Health Study

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: All Sister Study participants provided written informed consent. The Sister Study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Institute of Health.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest

Data availability Statement: Data used here may be requested through the Sister Study data management system; information on requesting data can be found at https://sisterstudy.niehs.nih.gov/English/data-requests.htm. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders CK, Hsu DS, Broadwater G, Acharya CR, Foekens JA, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Marcom PK, Marks JR, Febbo PG, Nevins JR, Potti A, et al. Young age at diagnosis correlates with worse prognosis and defines a subset of breast cancers with shared patterns of gene expression. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3324–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt J, Garne JP, Tengrup I, Manjer J. Age at diagnosis in relation to survival following breast cancer: a cohort study. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2015;13:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols HB, Schoemaker MJ, Wright LB, McGowan C, Brook MN, McClain KM, Jones ME, Adami H-O, Agnoli C, Baglietto L, Bernstein L, Bertrand KA, et al. The Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaboration: A Pooling Project of Studies Participating in the National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:1360–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou W, Chen X, Huang H, Liu S, Xie A, Lan L. Birth Weight and Incident of Breast Cancer: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Clinical Breast Cancer [Internet] 2020. [cited 2020 Jun 8];Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1526820920300896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Ajmi K, Lophatananon A, Ollier W, Muir KR. Risk of breast cancer in the UK biobank female cohort and its relationship to anthropometric and reproductive factors. PLoS One [Internet] 2018. [cited 2020 Jun 8];13. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6062099/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terry MB, Michels KB, Brody JG, Byrne C, Chen S, Jerry DJ, Malecki KMC, Martin MB, Miller RL, Neuhausen SL, Silk K, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Environmental exposures during windows of susceptibility for breast cancer: a framework for prevention research. Breast Cancer Research 2019;21:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaston SA, James-Todd T, Harmon Q, Taylor KW, Baird D, Jackson CL. Chemical/straightening and other hair product usage during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood among African-American women: potential implications for health. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2020;30:86–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo J-J, Kim H-Y. Use of Beauty Products among U.S. Adolescents: An Exploration of Media Influence. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 2010;1:172–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, Rudel RA, Dodson RE. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by Black women. Environmental Research 2018;165:448–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James-Todd T, Terry MB, Rich-Edwards J, Deierlein A, Senie R. Childhood Hair Product Use and Earlier Age at Menarche in a Racially Diverse Study Population: A Pilot Study. Ann Epidemiol 2011;21:461–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor KW, Baird DD, Herring AH, Engel LS, Nichols HB, Sandler DP, Troester MA. Associations among personal care product use patterns and exogenous hormone use in the NIEHS Sister Study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2017;27:458–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calafat A, Ye Xiaoyun, Wong Lee-Yang, Bishop Amber M., Needham Larry L. Urinary Concentrations of Four Parabens in the U.S. Population: NHANES 2005–2006. Environmental Health Perspectives 2010;118:679–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James-Todd TM, Meeker JD, Huang T, Hauser R, Seely EW, Ferguson KK, Rich-Edwards JW, McElrath TF. Racial and ethnic variations in phthalate metabolite concentration changes across full-term pregnancies. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 2017;27:160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson LC, Henley SJ, Miller JW, Massetti G, Thomas CC. Patterns and Trends in Age-Specific Black-White Differences in Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality – United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1093–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019–2020. 2019.

- 17.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, Deming SL, Geradts J, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 2006;295:2492–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien KM, Cole SR, Tse C-K, Perou CM, Carey LA, Foulkes WD, Dressler LG, Geradts J, Millikan RC. Intrinsic Breast Tumor Subtypes, Race, and Long-Term Survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:6100–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donovan M, Tiwary CM, Axelrod D, Sasco AJ, Jones L, Hajek R, Sauber E, Kuo J, Davis DL. Personal care products that contain estrogens or xenoestrogens may increase breast cancer risk. Med Hypotheses 2007;68:756–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James-Todd T, Senie R, Terry MB. Racial/ethnic differences in hormonally-active hair product use: a plausible risk factor for health disparities. J Immigr Minor Health 2012;14:506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green A, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Bain C, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Use of permanent hair dyes and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1987;79:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heikkinen S, Pitkäniemi J, Sarkeala T, Malila N, Koskenvuo M. Does Hair Dye Use Increase the Risk of Breast Cancer? A Population-Based Case-Control Study of Finnish Women. PLoS One [Internet] 2015. [cited 2020 Mar 30];10. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4532449/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koenig KL, Pasternack BS, Shore RE, Strax P. Hair dye use and breast cancer: a case-control study among screening participants. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:985–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llanos AA, Rabkin A, Bandera EV, Zirpoli G, Gonzalez BD, Xing CY, Qin B, Lin Y, Hong C-C, Demissie K, Ambrosone CB. Hair product use and breast cancer risk among African American and White women. Carcinogenesis 2017;38:883–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendelsohn JB, Li Q-Z, Ji B-T, Shu X-O, Yang G, Li H-L, Lee K-M, Yu K, Rothman N, Gao Y-T, Zheng W, Chow W-H. Personal use of hair dye and cancer risk in a prospective cohort of Chinese women. Cancer Sci 2009;100:1088–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stavraky KM, Clarke EA, Donner A. Case-control study of hair dye use by patients with breast cancer and endometrial cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1979;63:941–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eberle CE, Sandler DP, Taylor KW, White AJ. Hair dye and chemical straightener use and breast cancer risk in a large US population of black and white women. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CANCER 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler DP, Hodgson ME, Deming-Halverson SL, Juras PS, D’Aloisio AA, Suarez LM, Kleeberger CA, Shore DL, DeRoo LA, Taylor JA, Weinberg CR, the Sister Study Research Team. The Sister Study Cohort: Baseline Methods and Participant Characteristics. Environ Health Perspect 2017;125:127003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Aloisio AA, Nichols HB, Hodgson ME, Deming-Halverson SL, Sandler DP. Validity of self-reported breast cancer characteristics in a nationwide cohort of women with a family history of breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2017;17:692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue X, Kim MY, Gaudet MM, Park Y, Heo M, Hollenbeck AR, Strickler HD, Gunter MJ. A Comparison of the Polytomous Logistic Regression and Joint Cox Proportional Hazards Models for Evaluating Multiple Disease Subtypes in Prospective Cohort Studies. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 2013;22:275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breslow N. Discussion on Professor Cox’s Paper. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1972;34:202–20. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ambrosone CB, Abrams SM, Gorlewska-Roberts K, Kadlubar FF. Hair dye use, meat intake, and tobacco exposure and presence of carcinogen-DNA adducts in exfoliated breast ductal epithelial cells. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2007;464:169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson GM, Jönsson BAG, Axmon A, Lindh CH, Lind M-L, Gustavsson M, Broberg K, Boman A, Meding B, Lidén C, Albin M. Exposure of hairdressers to ortho- and meta-toluidine in hair dyes. Occup Environ Med 2015;72:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turesky RJ, Freeman JP, Holland RD, Nestorick DM, Miller DW, Ratnasinghe DL, Kadlubar FF. Identification of aminobiphenyl derivatives in commercial hair dyes. Chem Res Toxicol 2003;16:1162–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2013;12:144–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwegbue CMA, Emakunu OS, Obi G, Nwajei GE, Martincigh BS. Evaluation of human exposure to metals from some commonly used hair care products in Nigeria. Toxicol Rep 2016;3:796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoemaker MJ, Nichols HB, Wright LB, Brook MN, Jones ME, O’Brien KM, Adami H-O, Baglietto L, Bernstein L, Bertrand KA, Boutron-Ruault M-C, Braaten T, et al. Association of Body Mass Index and Age With Subsequent Breast Cancer Risk in Premenopausal Women. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e181771–e181771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White AJ, Nichols HB, Bradshaw PT, Sandler DP. Overall and central adiposity and breast cancer risk in the Sister Study. Cancer 2015;121:3700–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kasum M, Beketić-Orešković L, Peddi PF, Orešković S, Johnson RH. Fertility after breast cancer treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;173:13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brinton LA, Figueroa JD, Ansong D, Nyarko KM, Wiafe S, Yarney J, Biritwum R, Brotzman M, Thistle JE, Adjei E, Aitpillah F, Dedey F, et al. Skin lighteners and hair relaxers as risk factors for breast cancer: results from the Ghana breast health study. Carcinogenesis 2018;39:571–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg L, Boggs DA, Adams-Campbell LL, Palmer JR. Hair Relaxers Not Associated with Breast Cancer Risk: Evidence from the Black Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16:1035–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Birmann BM, Han J, Giovannucci EL, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Schernhammer ES. Personal use of permanent hair dyes and cancer risk and mortality in US women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020;m2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humans IWG on the E of CR to. Some Aromatic Amines, Organic Dyes, and Related Exposures. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hair Dyes and Cancer Risk - National Cancer Institute [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2020 Oct 16];Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/myths/hair-dyes-fact-sheet

- 45.Ward JB, Gartner DR, Keyes KM, Fliss MD, McClure ES, Robinson WR. How do we assess a racial disparity in health? Distribution, interaction, and interpretation in epidemiological studies. Annals of Epidemiology 2019;29:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.