Abstract

Background:

Accurate characterization of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) is challenging due to inconsistent use of screening questionnaires in routine prenatal care and substantial underreporting due to stigma associated with alcohol use in pregnancy. The aim of this study is to identify self-report tools that are efficient in accurate characterization of PAE.

Methods:

Participants meeting eligibility criteria for mild-to-moderate PAE who completed the baseline study visit were recruited into the prospective University of New Mexico ENRICH cohort (N=121). Timeline follow-back (TLFB) interviews were administered to capture alcohol use in the periconceptional period and 30 days before enrollment; reported quantity was converted to oz absolute alcohol (AA), multiplied by frequency of use and averaged across two TLBF calendars. The interview also included questions about timing and number of drinks at the most recent drinking episode, maximum number of drinks in a 24-hour period since last menstrual period, and number of drinks on ‘special occasions’ (irrespective of whether these occurred within the TLFB reported period). Continuous measures of alcohol use were analyzed to yield number of binge episodes by participants who consumed ≥4 drinks/occasion. Proportion of women with ≥1 binge episode was also tabulated for each type of assessment.

Results:

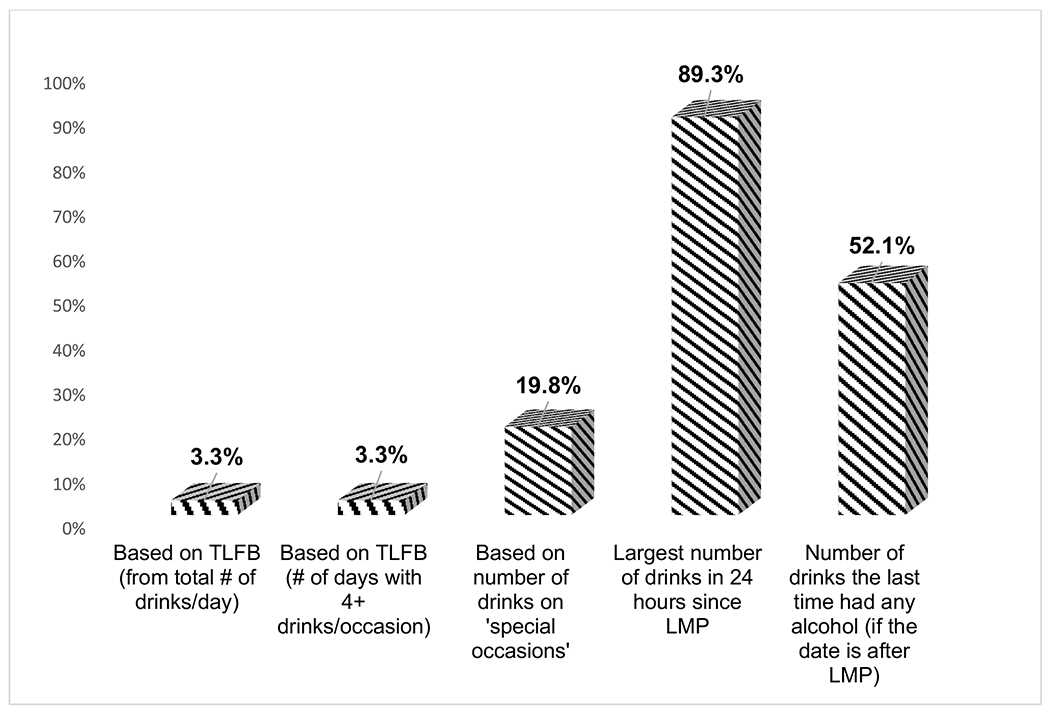

Average alcohol consumption was 0.6±1.3 oz of AA/day (≈ 8.4 drinks/week). Only 3.3% of participants reported ≥1 binge episode on the TLFB, 19.8% had ≥1 when asked about ‘special occasions,’ and 52.1% when asked about number of drinks the last time they drank alcohol. Even higher prevalence (89.3%) of bingeing was obtained based on maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period.

Conclusions:

Self-reported quantity of alcohol use varies greatly based on type of questions asked. Brief targeted questions about maximum number of drinks in 24 hours and total number of drinks at the most recent drinking episode provide much higher estimates of alcohol use and thus might be less affected by self-reporting bias.

Keywords: prenatal alcohol exposure, binge drinking, questionnaires, screening, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol is a well-established teratogen associated with life-long impairments in affected individuals who are identified as having fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Current prevalence estimates at 1.1 - 5.0% among school-aged children place FASD as the most common preventable developmental disorders in the U.S. (May et al., 2018). Diagnosis of less severe nonsyndromal cases of FASD without the characteristic facial dysmorphia require documentation of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) (Riley et al., 2011). Due to the stigma associated with PAE, challenges in identifying children without facial dysmorphia, and variability in behavioral phenotype, more than 80% of children with FASD go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed until school-age (Chasnoff et al., 2015, May et al., 2018, Bakhireva et al., 2017), preventing them from receiving early and appropriate interventions. The ambiguity about PAE often results in further delays in diagnosis and access to services for affected children (Bakhireva et al., 2017).

Accurate assessment of alcohol use in pregnancy in routine prenatal care is challenging due to associated stigma, fear of legal consequences, inconsistent screening, limited tools to elicit honest responses, and limited resources for referral and treatment. It is important to recognize that despite recommendated universal screening for alcohol and other drug use in pregnancy, prenatal substance use screening cannot result in accurate self-report if judgmental language (as exemplified in the title of this commentary), subjective questioning, or unwarranted assumptions about patient’s alcohol consumption level based on socio-demographic characteristics are employed (Trocin et al., 2020). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Antepartum Record can be used to ascertain the amount of alcohol use before and during pregnancy and the number of years of alcohol use (Chang, 2014). ACOG also recommends use of screening questionnaires to identify signs of alcohol abuse/dependence (ACOG, 2011). Accuracy of these tools is acceptable for identification of chronic heavy use, alcohol dependence, and alcohol use disorders but drops dramatically for episodic binge drinking or moderate consumption (Chang, 2014). It is important to note that moderate alcohol consumption is equally important to accurately ascertain, given that there is no established threshold below which alcohol consumption is deemed safe during pregnancy (Riley et al., 2011). In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a new diagnostic category, Neurodevelopmental Disorder Associated with PAE (ND-PAE), was introduced under “Conditions for further study,” defining the PAE risk threshold as >13 drinks/month during pregnancy, a cut-point that the authors acknowledged was not empirically based and in need of prospective longitudinal research to study the effects at this exposure level (Kable and Mukherjee, 2017).

A growing body of literature, including our findings, advocates for the combined use of self-reported measures and ethanol biomarkers (Bakhireva and Savage, 2011); however, self-report remains the most widely used and accessible method to screen for alcohol use during routine prenatal care. Acknowledging the ethical and legal issues associated with screening for substance use in pregnancy (Zizzo et al., 2013), which are beyond the scope of this report, the aim of the current study was to compare the prevalence of self-reported alcohol use obtained using different approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The study sample consists of participants from the Ethanol, Neurodevelopment, Infant and Child Health (ENRICH-1) cohort (Bakhireva et al., 2018a), who were recruited from the University of New Mexico prenatal clinics from October 2013-August 2017. The ENRICH-1 cohort study focused on the effects of moderate alcohol and/or opioid exposure in pregnancy on development and includes four study visits (i.e., prenatal, at delivery/birth, at 6 months postpartum, and at 20 months postpartum). Four groups of pregnant women in the ENRICH-1 study were recruited: healthy controls who did not use alcohol or opioids during pregnancy, women who used alcohol during pregnancy (Alcohol), patients receiving medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder (MOUD) who did not use alcohol during pregnancy, and MOUD patients who concurrently used alcohol (MOUD+Alcohol).

For purposes of the analysis in this paper, the sample was restricted to 121 women who completed the baseline visit (on average at 24.3 weeks gestation) and had been classified as either Alcohol or MOUD+Alcohol. Participants recruited into the MOUD and healthy control groups were excluded from this analysis since “any alcohol use during pregnancy” was an exclusionary criteria for those groups. The following criteria had to be met in order to be classified into either of the two alcohol-using groups: 1) a score of ≥ 2 on the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C) questionnaire and 2) ≥2 binge drinking episodes in the time between the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP) and pregnancy recognition OR ≥ 3 drinks per week on average in the period between LMP and pregnancy recognition. Binge drinking was defined as consumption of 4 or more standard drinks on at least one occasion. At the baseline visit, eligible and consented participants participated in the semi-structured questionnaire and collection of biospecimens (blood, urine). The University of New Mexico (UNM) Human Research Review Committee (HRRC) approved all study procedures.

Procedure

Demographic information was collected from each participant. Alcohol use was ascertained using a TLFB interview (Jacobson et al., 2002), which captured alcohol use in the past 30 days and generated total number of drinks and number of binge episodes. In the TLFB, the mother was interviewed individually to determine incidence and amount of drinking on a day-by-day basis during the periconceptional period (i.e., 2 weeks prior and 2 weeks following LMP) and the 30-day period before enrollment. Recall was linked to specific times of day and activities and volume was recorded for each type of beverage consumed each day, converted to absolute alcohol (AA) using multipliers proposed by Bowman et al. (1975), and averaged across two TLFB calendars. One oz of AA is equivalent to ≈ 2 standard drinks.

The maternal interview also included questions about timing of alcohol use and number of drinks the last time the individual had any alcohol, maximum number of drinks in a 24-hour period since the LMP, number of drinks on ‘special occasions’ (e.g., holidays, birthdays) when the individual might consume greater quantities of alcohol than usual. These questions were focused on the periconceptional period (i.e., 2 weeks prior and 2 weeks following LMP) and for the time window from LMP to the baseline visit. The standard ACOG approach for estimating pregnancy dating and expected date of delivery (EDD) was used (ACOG, 2017). When asked to report maximum number of drinks in a 24-hour period, participants were provided with the dates between their LMP date (actual or estimated) and the date of the interview. They were asked to report the date of the last time they had any alcohol and the number of drinks consumed on that date, which was later compared to the LMP to determine if drinking happened during pregnancy or before. Continuous measures of alcohol intake were converted into binge episodes if participants reported consuming ≥ 4 drinks per occasion, the amount of alcohol intake considered a binge for female drinkers.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the demographic and medical characteristics and alcohol consumption patterns. The summary for continuous variables included means and standard deviations, along with medians and inter-quartile range (Q1-Q3) for non-normally distributed variables, and proportions for categorical variables. The proportion of women with ≥ 1 binge episode was calculated for each type of assessment. Dates of the last drinking episode were compared to the LMP date; only alcohol use after LMP was considered in this analysis. Although to date there is no ‘gold standard’ or biomarker by which to definitively confirm alcohol use, for purposes of this analysis we considered responses reporting higher use to represent more honest/accurate information.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. Women ranged in age at enrollment from 18 to 43 years, and the majority of participants were recruited during the second trimester (mean gestational age 24.3±7.1 weeks). The majority of the study participants were Hispanic/Latina (61.2%) and more than 10% were American Indian women. Participants with both low (19.8% less than high school) and relatively high (57.9% some college or higher) level of education were represented in the sample. Only 44.6% of the women were employed at enrollment, 70.2% were covered by Medicaid and 36.4% were living without a partner. Mean alcohol consumption in the periconceptional period and 30 days before the baseline interview were 1.83±4.05 and 0.05±0.32 oz of AA per day, respectively, resulting in an average across two TLFB calendars of 0.94±2.07 (median: 0.28; Q1: 0.16, Q3: 0.62, equivalent to approximately 4 standard drinks per week).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics (N=121)

| Patient characteristics | Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Maternal age at enrollment (years) | 28.6±5.7 |

| Gestational age at enrollment (weeks) | 24.3±7.1 |

| Absolute oz of alcohol/daya | 0.94±2.07 |

| n (%) | |

| Marital/cohabiting status: | |

| Single/separated/divorced | 44 (36.4) |

| Married/cohabitating | 77 (63.6) |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic/Latina | 74 (61.2) |

| Race: | |

| African American | 4 (3.3) |

| American Indian | 14 (11.6) |

| Other | 4 (3.3) |

| White | 99 (81.8) |

| Education level: | |

| Less than high school | 24 (19.8) |

| High school graduate or GED | 27 (22.3) |

| Some college or higher | 70 (57.9) |

| Employed (at enrollment) | 54 (44.6) |

| Health insurance status: | |

| Employer-based/Self-Purchased/Other | 34 (28.1) |

| Medicaid Insurance | 85 (70.2) |

| No insurance | 2 (1.7) |

| Receiving MOUD | 53 (43.8) |

Averaged among two TLFB calendars including periconceptional period and 30 days before enrollment.

MOUD, medications for opioid use disorder

Only 3.3% of the participants reported at least one binge episode on the TLFB calendar interview (Figure 1). In contrast, 19.8% had ≥1 binge episode when asked about ‘special occasions’ and 52.1% when asked about number of drinks the last time they had any alcohol. (Note that only dates after LMP were considered in calculating this proportion). Even higher prevalence (89.3%) was obtained when the women were asked about maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period. Participants were not asked ‘since pregnancy’ but were given a timeframe between estimated LMP and date of the interview. No statistically significant differences were observed in the proportion of women with ≥ 1 binge episode for each type of assessment by MOUD status, race, ethnicity, or education levels (all p’s > 0.05; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Proportion of Gravidas with at Least 1 Binge Episode (≥4 drinks/occasion) based on Different Self-Reported Assessment Approaches

DISCUSSION

Self-reported quantity of occasional binge drinking varies greatly based on the type of questions asked. Whereas prospective, repeated, in-depth TLFB interviews are considered the best research tool to quantify alcohol use across pregnancy, they do not provide a good ‘snapshot’ when administered once. Moreover, the TLFB interview takes approximately 30-45 minutes to administer and is thus not a realistic option in a clinical setting. Brief targeted questions about maximum number of drinks in 24 hours and total number of drinks at the most recent drinking episode appear to provide the most valid estimate of binge drinking, especially in early pregnancy.

A systematic review of the screening questionnaires evaluated cumulatively among 6724 pregnant women demonstrated relatively high sensitivity (69-95%) and moderate specificity (71-85%) for the T-ACE (Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut down, Eye-opener), TWEAK (Tolerance, Worried, Eye-opener, Amnesia, K(C)ut down), and AUDIT-C questionnaires for the identification of risky drinking and even high validity for the last year regarding alcohol dependence or alcohol use disorder (Burns et al., 2010). Focus groups with pregnant women and new mothers found that in-depth questions on alcohol consumption might be anxiety-generating and suggestive of an underlying potential for harm to the fetus (Muggli et al., 2015). Complexity of the study instrument, especially when women were asked to recall alcohol consumption during different stages of pregnancy, use of subjective language, and difficulties with recall were identified as potential limitations for accurate reporting. Similar to our findings, qualitative research study indicated that the question about ‘special occasions’ helped women more accurately report occasional high-intake events, which might not be captured by questions about ‘typical’ drinking behavior (Muggli et al., 2015).

Study findings should be viewed in light of their limitations. First, the prevalence of alcohol use was ascertained in a group of pregnant women pre-screened into the alcohol exposure study group by disclosing either at least one binge drinking episode or an average consumption of at least 3 drinks per week in pregnancy. Additionally, the sample included high risk women on MOUD. While such sampling cannot be used to estimate prevalence of alcohol use in all pregnant women, it allows for comparison of the validity of different questions used to estimate frequency of risky drinking. We have previously reported that the prevalence of any alcohol use in periconceptional period and early pregnancy is similar in pregnant women on MOUD and the general obstetrics population; however, level of alcohol consumption is higher in the MOUD group (Bakhireva et al., 2018b). It is important to note though that in the general population of pregnant women as many as 30% report alcohol use sometime during pregnancy (Ethen et al., 2009), 7.5-24.7% might engage in binge drinking behavior in early pregnancy (Ethen et al., 2009, Bakhireva et al., 2018b) and 2.8-8.3% anytime during pregnancy (Ethen et al., 2009, Popova et al., 2018). Additionally, pregnant women across all socio-economic and ethnic background groups might be at risk of drinking excessively or bingeing during pregnancy (Perreira and Cortes, 2006). This is consistent with our findings demonstrating no differences in reported alcohol use by racial/ethnic and education levels; however, we cannot definitively conclude whether this indicates lack of differences in reporting or alcohol consumption pattern among different subgroups.

Second, this paper compares frequency of binge drinking as obtained using an in-depth TLFB calendar interview and additional individual questions. While our study findings indicate that individual questions about the maximum number of drinks in 24 hours and total number of drinks at the most recent drinking episode result in higher disclosure, validity of these questions needs to be assessed against validated alcohol screening tools. While it is unlikely that higher self-reported prevalence is driven by false positive responses, the current analysis does not estimate sensitivity and specificity of these brief questions. Future studies should compare validity of these questions against other brief screening questionnaires (e.g., TWEAK, T-ACE, AUDIT) and clinical tools (e.g., ACOG Antepartum Record) to ascertain alcohol use in pregnancy.

Binge drinking in early pregnancy, which can represent alcohol use prior to pregnancy recognition for many women, is predictive of risky drinking later in gestation and is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes (ACOG, 2011). Asking about alcohol consumption during the timeframe since estimated LMP, instead of asking directly about alcohol use ‘in pregnancy,’ may also elicit more honest responses. These brief and incisive questions, which can readily be asked by the clinician, generate information critical for the long-term health of the mother and infant. Future studies should further validate self-reported information against ethanol biomarkers, test feasibility and acceptability of targeted alcohol screening questionnaires in clinical settings for universal screening of PAE and determine what is the association between specific patterns of alcohol use during pregnancy with subsequent pregnancy outcomes as well as neurodevelopmental and behavioral outcomes in affected children.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mary Carmody, Lidia Enriquez Marquez, Xingya Ma, and Dr. Shikhar Shrestha (from the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center) for their work on data collection, data management, reference management, and preliminary analyses. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (research grant R01 AA021771) and the NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse (research grant 1R34DA050237) and the Lycaki-Young Grant from the State of Michigan.

Financial support: This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (research grant R01 AA021771) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (research grant 1R34DA050237) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NIH did not play any role in the study design, conclusions, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Paper presentation information: Preliminary results of this study were presented at the American Public Health Association (APHA) Annual Meeting and Expo; Philadelphia, PA, USA; November 2-6, 2019.

References:

- ACOG (2011) Committee opinion no. 496: At-risk drinking and alcohol dependence: obstetric and gynecologic implications. Obstet Gynecol 118:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACOG (2017) Committee opinion no. 700: Methods for estimating the due date. Obstet Gynecol 129:150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhireva LN, Garrison L, Shrestha S, Sharkis J, Miranda R, Rogers K (2017) Challenges of diagnosing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in foster and adopted children. Alcohol 67:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhireva LN, Lowe J, Garrison LM, Cano S, Leyva Y, Qeadan F, Stephen JM (2018a) Role of caregiver-reported outcomes in identification of children with prenatal alcohol exposure during the first year of life. Pediatr Res 84:362–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhireva LN, Savage DD (2011) Focus on: biomarkers of fetal alcohol exposure and fetal alcohol effects. Alcohol Res Health 34:56–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhireva LN, Shrestha S, Garrison L, Leeman L, Rayburn WF, Stephen JM (2018b) Prevalence of alcohol use in pregnant women with substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 187:305–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman RS, Stein LI, Newton JR (1975) Measurement and interpretation of drinking behavior: I. On measuring patterns of alcohol consumption: II. Relationships between drinking behavior and social adjustment in a sample of problem drinkers. J Stud Alcohol 36:1154–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns E, Gray R, Smith LA (2010) Brief screening questionnaires to identify problem drinking during pregnancy: a systematic review. Addiction 105:601–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G (2014) Screening for alcohol and drug use during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 41:205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasnoff IJ, Wells AM, King L (2015) Misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses in foster and adopted children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Pediatrics 135:264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethen MK, Ramadhani TA, Scheuerle AE, Canfield MA, Wyszynski DF, Druschel CM, Romitti PA (2009) Alcohol consumption by women before and during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 13:274–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Chiodo LM, Sokol RJ, Jacobson JL (2002) Validity of maternal report of prenatal alcohol, cocaine, and smoking in relation to neurobehavioral outcome. Pediatrics 109:815–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JA, Mukherjee RA (2017) Neurodevelopmental disorder associated with prenatal exposure to alcohol (ND-PAE): A proposed diagnostic method of capturing the neurocognitive phenotype of FASD. Eur J Med Genet 60:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Chambers CD, Kalberg WO, Zellner J, Feldman H, Buckley D, Kopald D, Hasken JM, Xu R, Honerkamp-Smith G, Taras H, Manning MA, Robinson LK, Adam MP, Abdul-Rahman O, Vaux K, Jewett T, Elliott AJ, Kable JA, Akshoomoff N, Falk D, Arroyo JA, Hereld D, Riley EP, Charness ME, Coles CD, Warren KR, Jones KL, Hoyme HE (2018) Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in 4 US communities. JAMA 319:474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggli E, Cook B, O’Leary C, Forster D, Halliday J (2015) Increasing accurate self-report in surveys of pregnancy alcohol use. Midwifery 31:23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Cortes KE (2006) Race/ethnicity and nativity differences in alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. Am J Public Health 96:1629–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J (2018) Global prevalence of alcohol use and binge drinking during pregnancy, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Biochem Cell Biol 96:237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EP, Infante MA, Warren KR (2011) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview. Neuropsychol Rev 21:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocin KE, Weinstein NI, Oga EA, Mark KS, Coleman-Cowger VH (2020) Prenatal Practice Staff Perceptions of Three Substance Use Screening Tools for Pregnant Women. J Addict Med 14:139–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizzo N, Di Pietro N, Green C, Reynolds J, Bell E, Racine E (2013) Comments and reflections on ethics in screening for biomarkers of prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:1451–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]