Abstract

Cancer precision medicine aims to improve patient outcomes by tailoring treatment to the unique genomic background of a tumor. However, efforts to develop prognostic and drug response biomarkers largely rely on bulk “omic” data, which fails to capture intratumor heterogeneity and deconvolve signals from normal versus tumor cells. These shortcomings in measuring clinically relevant features are being addressed with single-cell technologies, which provide a fine-resolution map of the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity in tumors and their microenvironment, as well as an improved understanding of the patterns of subclonal tumor populations. Here we present recent advances in the application of single-cell technologies towards gaining a deeper understanding of intratumor heterogeneity and evolution and potential applications in developing personalized therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: tumor heterogeneity, single-cell sequencing, clonal evolution, biomarkers, tumor microenvironment

Tailoring cancer therapy based on the genetic background of tumors

Cancer incidence and mortality rates are projected to climb worldwide over the next several decades [1]. Thus, there is a pressing need to improve the clinical management of cancers by optimizing drug treatment strategies for each tumor individually. The discovery of tumor-specific somatic mutations and alterations that can be targeted with drugs has led to significant improvement in the management and survival outcomes in certain cancers, like tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that target the BCR-ABL1 fusion protein in chronic myeloid leukemia [2], anti-EGFR TKIs for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancers [3] or monoclonal antibodies and TKIs against HER2 in breast cancers [4]. These therapeutic approaches rely on classifying tumors as responsive or not to therapy based on tumor genomes and transcriptomes at the baseline before treatment has been initiated. To this end, bulk “omic” technologies (DNA-seq, RNA-seq) have enabled the discovery of biomarkers of drug response and patient prognosis by characterizing the tumor genome and transcriptome and its evolution over time (see Box 1). Single-cell technologies are further advancing the scope of information gained through bulk approaches by characterizing molecular information at an unprecedented level of detail and improve the inference of intratumor heterogeneity (ITH). In the past few years, single-cell technologies have found applications in various fields of cancer biology, including genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and pathology. Further development of multiplexed assays provides unique opportunities to characterize ITH by simultaneous characterization of different molecular properties, such as transcriptomes and epigenomes, which by paint a detailed picture of the regulatory states in each cell. Table 1 includes definitions of a selection of single-cell technologies along with a summary of their applications across various fields and references with more detailed information on the advantages and caveats of these methods.

Box 1: Success and pitfalls of bulk omics in cancer precision medicine.

Large-scale genomic studies such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) have provided a roadmap to the genetic alterations found in cancer subtypes prior to treatment [74,75]. In addition, pre-clinical drug-screens combined with bulk omic data [76–78] have enabled the development of new machine-learning and systems biology approaches for biomarker discovery [79–82]. As bulk sequencing is performed on a mixture of cancer and normal cells, the resulting averaged genomes and transcriptomes cannot distinguish the contribution of the components of the tumor microenvironment (TME), which influence tumor growth, maintenance, and immune surveillance [83]. For example, with bulk RNA-sequencing, if an immune signature is found to be upregulated, it is unknown if that signal is derived from cancer or normal infiltrating immune cells in a tumor [84]. This issue was highlighted in a TCGA analysis, where over 10,000 sequenced tumors were demonstrated to have an average purity of only ~60–70%, resulting in widespread systemic biases in downstream analyses [85]. Consequently, bulk technologies tend to underestimates ITH as well as the impact of the dynamic nature of tumors on drug response (reviewed in [86]). Indeed, many prior biomarker studies with bulk sequencing data fail to identify innate or acquired resistant properties in tumors [87–89].

Current theory indicates that cancers undergo adaptive Darwinian evolution through reiterative processes of clonal selection and diversification, sometimes driven by specific driver mutations or structural variations [41]. Inferring the subclonal structure of individual tumors may provide crucial insights into how tumors evolve under the selection pressure of treatment and eventually develop resistance. Bulk DNA-seq data has enabled the approximation of the subclonal structure of tumors based on somatic single-nucleotide variations (SNV) and copy number alterations (CNA) that accumulate within specific subpopulations (reviewed in [90]). Such approaches have been implemented to estimate the patterns of genetic evolution in malignant cells from chronic lymphocytic leukemia [91] and renal cell carcinoma [92]. These studies revealed an important association between subclonal dynamics and tumor growth and progression, suggesting the evolutionary structure of the tumors could serve as a prognostic biomarker. Bulk DNA-seq also finds application in profiling somatic variants in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from liquid biopsies [93,94]. These are elegant approaches that enable the characterization of clonal populations based on known variants and can inform prognosis in instances where serial tumor biopsies or tissues are not feasible to collect. Despite these successes, bulk DNA-seq applications suffer from a major limitation. Aggregating and clustering subclonal populations on average variant allele frequencies of SNVs and CNAs can lead to incorrect subclone classification, especially in the presence of small subclonal populations defined by low-frequency variants. Further, transcriptomic changes that lead to or result from clonal evolution can include drug-resistant phenotypes that differ among subclonal populations [48] that would be masked in bulk sequencing [95,96]. Indeed, studies show that even cancer cell lines believed to be genetically uniform show transcriptionally heterogeneous subpopulations resistant to therapy as revealed by scRNA-seq [97].

Table 1:

Overview of single-cell technologies and applications

| Fieldy | Technologies | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell isolation | Separation based on physical characteristics, laser capture microdissection (LCM), FluorescenceActivated Cell Sorting (FACS), Magnetic Activated Cell Sorting (MACS), and microfluidics [98]. | Foundation for all single-cell profiling technologies. |

| Genomics (genetics) | Single-cell DNA-seq (scDNA-seq) based on multiple annealing and looping-based amplification cycles (MALBAC) [99], multiple displacement amplification (MDA) [100]. |

Detection of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and copy number alterations (CNAs) in single-cell somatic genomes. Inference of subclonal evolutionary trees and ITH characterization [101,102]. Sparse and uneven coverage across cells require complex mathematical models for inference. Confirmation with bulk genome sequencing may help at the cost of missing rare subclones. |

| Transcriptomics (including functional genomics) | Single-cell RNA (scRNA-seq) based on SMART-seq [103], Chromium (10X) [104], CEL-seq [105], Quartz-seq [106], Drop-seq [107]. |

Identification of cellular communities [108], classification of cell types and separation of malignant cells from normal cells in the tumor microenvironment [109], inference of cell trajectories [110], identification of differentially expressed genes in cellular communities [111], inference of cellular phenotypes [112] and network reconstruction [113]. ScRNAseq data can be noisy with high variability due to low coverage. Appropriate data normalization and batch-correction are essential for comparative analyses and ITH inference [114]. |

| Epigenomics | Single-cell DNA methylation analysis based on whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (scWGBS) [115] and reducedrepresentation bisulfite sequencing (scRRBS) [116]. Inference of chromatic accessibility and chromosomal conformation based on assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (scATAC-seq) [117] and chromosome conformation capture (scHi-C) [118]. Profiling histone modifications using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (scChIP-seq) [119]. |

Determining the diversity and state of gene regulation in individual cancer cells, inferring subclonal structure, and ITH [120,121]. Augment assessment of cellular diversity due to greater stability of the epigenome over transcriptome and have the potential be used with archival (FFPE) material. |

| Proteomics and metabolomics | Determining the expression of proteins in single cells using mass cytometry (CyTOF) [122] and mass spectrometry (SCoPE-MS) [123]. Using mass spectrometry to determine metabolomic profiles of single cells (SCM) [124]. |

Determining cellular diversity and ITH. Current methods are low throughput, and few targets can be analyzed, but provide a direct measurement of proteins and metabolites instead of relying on gene expression for indirect inference [124,125]. |

| Pathology | Single-cell imaging of tissue samples with multiple probes based on multiplexed ion beam imaging (MIBI) [40] and co-detection by indexing (CODEX) [126] | Deep pathological classification and ITH assessment. Multiplexed assays measure several targets in archival (FFPE) samples. |

| Multi-omics | Multiplexed assessment of single-cell expression and surface proteins using cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) [127]. Parallel genome and transcriptome sequencing (G&T-seq) [128]. Multiplexed assessment of single-cell transcriptomes and epigenomes using chromatin accessibility and transcriptome sequencing (scCAT-seq) [129] and single-nucleus chromatin accessibility and mRNA expression sequencing (SNARE-seq) [129] |

Matched assessment of transcriptomes and proteins/genome/epigenomes for more accurate inference of the regulatory states in single-cells. |

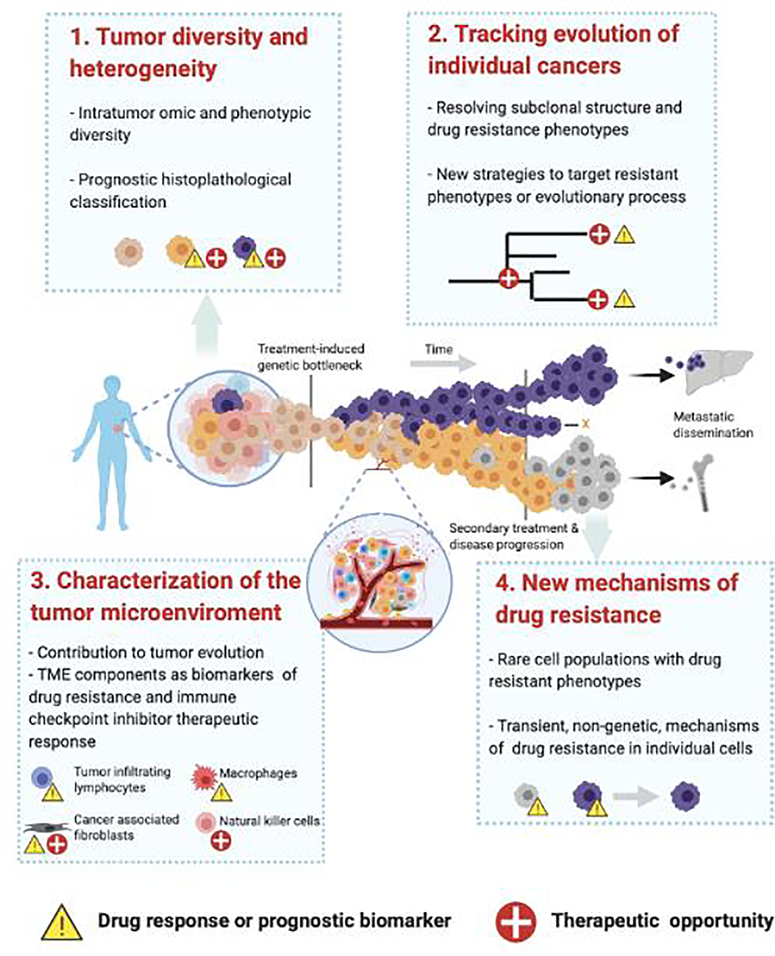

In the following sections, we discuss the applications of single-cell methods in advancing cancer precision medicine focusing on four key areas (Figure 1, Key Figure). We first highlight the applications of various single-cell technologies in elucidating the molecular diversity (somatic mutations, epigenetics, gene and protein expression) of malignant cell populations, characterization of ITH, and prognostic classification. Next, we explore applications of single-cell methods to infer the evolutionary structure of tumors and inform therapeutic strategies to target resistance. We then discuss how single cell analysis enables the study of normal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Finally, we discuss emerging applications of single cell approaches; specifically, the study of rare cells within a tumor as well as epigenetic signaling diversity in a tumor and during treatment.

Figure 1, Key Figure: Strategies to harness single-cell technologies in cancer precision medicine.

The figure depicts ITH and the evolution of cancer over time as the central challenge of cancer precision medicine. 1. Tumor diversity and heterogeneity: primary tumors may be composed of a diverse population of cells, as shown by cells of different colors. Each group of cells with a shared genetic background is defined as a “subclone”. However, cellular diversity can be manifested at the molecular level via differences in the genome, transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, and at the phenotypic level. Various single-cell technologies provide opportunities to develop new biomarkers and therapeutic strategies that account for cellular diversity. 2. Tracking the evolution of individual cancers: as tumors respond to treatment, the sensitive cell populations are lost and leave a small proportion of the original population behind, resulting in a “genetic bottleneck”. These resistant subclones can undergo expansion and further evolution under the selection pressure of additional treatments. Single-cell approaches to characterize the subclonal diversity and evolution can help define the drivers and develop strategies to counter the emergence of resistance. 3. Characterization of the TME: Besides the malignant cell population, the cells in the TME interact and influence the growth, evolution, and influence responsiveness to therapy, especially, immune therapy. Ultimately, the presence of certain stromal and immune cell components is a strong predictor of patient prognosis. Thus, understanding the diversity of the TME with single-cell technologies provides opportunities to predict drug response and patient outcomes. 4. New mechanisms of drug resistance: Tumors continue to evolve and eventually acquire therapeutic resistance to secondary treatment. Some resistance mechanisms may be driven by rare and transient cell states that are not easily captured by single-molecule approaches. New integrated approaches that integrate multiple single-cell technologies can help identify such rare cell states that can serve as prognostic biomarkers. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Tumor diversity and heterogeneity

Transcriptomics

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) provides a measurement of RNA expression for each individual cell within a tumor that is sampled and enables one to study the diversity of signaling states within a population of cancer and tumor-associated normal cells and their evolution as tumors progress. Here we discuss some examples applications of scRNA-seq and implications in cancer precision medicine.

Classification of tumors based on transcriptomes have been used for patient prognosis and drug response predictions [5–12]. For instance, the analysis of bulk transcriptomes from glioblastoma patients transcriptomes revealed the existence of at least four distinct subtypes with prognostic implications [13]. However, scRNA-seq analyses of glioblastomas revealed the existence of a multiple subtypes co-existing within the same tumor along a continuous spectrum in varying proportions within each tumor [14,15]. Subsequent analyses revealed these subclonal populations were driven by druggable genetic events like EGFR and PDGFRA amplification, suggesting new avenues of investigational treatment strategies against difficult to treat glioblastomas [16]. Furthermore, scRNA-seq analysis of PDGFRA-dependent glioblastomas revealed novel resistance mechanisms against tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment emerging from subclones with elevated IRS1/2 expression [17]. This study also highlighted that different genetic and epigenetic mechanisms were responsible for differential IRS expression, however they eventually converged on to a shared activation of the IRS/AKT signaling pathway. In a separate study, scRNA-seq analysis of triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) revealed that populations with distinct expression signatures co-existed within each tumor, and were correlated with survival outcomes of the patients [18]. For example, a population enriched in glycosphingolipid and innate immunity pathway signatures was associated with poor patient outcomes that could not be distinguished using bulk transcriptome signatures. Another scRNA-seq study focusing on patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of TNBC found that a specific tumor subpopulation with high EGFR expression were exceptional responders to anti-EGFR therapy, while tumor subpopulations without high expression of EGFR did not respond [19].

As a last example, activation of KRAS in lung cancer is a predictor of poor prognosis and there are no specific treatment strategies against these tumors. Bulk sequencing analysis of KRAS-mutant tumors suggest such tumors are resistant to chemotherapy and generally respond poorly towards targeted therapeutics. However, an scRNA-seq analysis of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma PDX model revealed that certain malignant cell populations with high KRAS activity were more responsive to chemotherapy and certain targeted therapies [20]. This study suggested that another cell population besides the KRAS-mutants may be responsible for overall resistance to drug resistance and poor prognosis of lung adenocarcinomas. Similar to these observations, scRNA-seq analysis of B-cell lymphomas revealed distinct classes co-existed within tumors and showed differential drug response in an ex vivo model [21]. These scRNA-seq studies revealed the diversity of malignant cell populations with prognostic implications which could not be captured with bulk transcriptomics.

In the clinic, scRNA-seq profiles are also being used in prospective studies of tumor heterogeneity using circulating tumor cells (CTCs), where obtaining sufficient tumor samples over the course of disease progression may otherwise be impractical. An scRNA-seq analysis of CTCs from non-small cell lung cancer found distinct subpopulations of metastatic and non-metastatic cancer cells [22]. This study led to the development of a new transcriptomic biomarker for lung cancer prognosis that improved upon the performance of current histopathological and single-gene classifiers. Another scRNA-seq of small cell lung cancer CTCs reported a prognostic association between the overall extent of intratumor heterogeneity and therapeutic response [23]. An scRNA-seq analysis of CTCs from gastrointestinal cancer patients revealed that both the abundance of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and the enrichment of specific phenotypes, like IFN signaling and T-cell differentiation, were predictive of response to anti-PD-1 therapy [24]. These initial efforts highlight the feasibility of applying scRNA-seq technologies for non-invasive assessment of tumor heterogeneity in the clinic.

Tumor scRNA-seq profiles may also serve as an attractive avenue for the development of drug response biomarkers based on predictive models. One such investigational study used scRNA-seq profiles to develop response prediction models to stratify renal cell carcinomas [25]. This early effort with a small sample size showed a promising gain in predictive accuracy when compared to bulk transcriptome and successfully guided the selection of combination treatment strategies for individual tumors.

These examples highlight the utility of scRNA-seq in elucidating drug response mechanisms and biomarkers in heterogenous tumors that were not possible with bulk technologies.

Genomics and epigenomics

Understanding the genetic and epigenetic makeup of tumors is crucial in understanding why certain cancers respond to therapy while others develop resistance. However, bulk approaches to estimate somatic mutations, chromosomal structures or epigenetic modifications often mask the differences between unique subpopulations within a tumor. Single-cell technologies to profile the genome and epigenome from diverse malignant cell populations are perhaps most useful in unraveling the evolutionary structure of tumors (discussed further in section 2). Here, we discuss specific clinical applications in estimating the heterogenous state of cancer cells with prognostic value.

Early applications of scDNA-seq featured targeted evaluation of specific gene variants with prognostic value. For example, the analysis of PIK3CA variants in CTCs obtained from triple-negative breast cancers revealed heterogeneity within a patient [26]. This study found that PIK3CA variants in the single cells of bone metastases were more diverse from the variants found in the CTCs, suggesting drug refractory states maybe better reflected in the heterogenous cancer cell populations in the metastases compared to CTCs. A subsequent study of triple-negative breast cancers also reported the presence of pathogenic PIK3CA mutations in the malignant single cells derived from bone marrow metastases, which were absent in primary and non-metastatic tumors [27]. Targeted scDNA-seq analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and CTCs from metastatic breast cancers found persistent heterogeneity in pathogenic variants of PIK3CA, TP53, ESR1 and KRAS genes that were correlated with metastatic burden and prognostic implications [28].

Whole-genome amplification of single cell genomes have also aided in the detection of heterogeneity in structural and copy number variants across malignant cells. For example, whole-genome scDNA-seq analysis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma revealed extensive heterogeneity in CNAs across single cells arising from chromosomal instability [29]. This study reported frequent loss of tumor suppressors and DNA repair genes in subpopulations that emerged later. Another scDNA-seq analysis focusing on heterogeneity across non-malignant single B-lymphocytes revealed that most SNVs were unique to each cell, with few shared variants across cells from different donors [30]. Interestingly, the rate of accumulation of SNVs increased with age, while the mutational signatures observed in B-cell cancers were elevated in the cells from older donors. A similar observation was reported in a scDNA-seq analysis of stem and differentiated liver cells, where frequency of somatic mutations increased significantly in differentiated hepatocytes with age across heterogenous single cell populations [31].

Methods to assess the cancer cell epigenome are also being extended to study the heterogenous regulatory state of single cells. An scATAC-seq analysis of K562 chronic myeloid leukemia cells to assess genome-wide chromatin accessibility revealed variations in accessibility of the GATA motif across single cells [32]. This study found concurrent appearance of high GATA and high CD24 cell surface marker expressing cells to be resistant to imatinib. An analysis of the single-cell methylation profiles of CTCs from breast and prostate cancer patients found heterogenous promoter methylation status of key genes associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). For example, methylation levels in promoter of the mir-200 family of EMT suppressors genes were significantly higher in single cells from metastatic prostate cancer [33]. Another study applied an scChIP-seq approach to study the chromatin states of breast cancer PDX cells by profiling the status of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 histone marks across single cells [34]. Analysis of the chromosomal marks revealed unique regions in drug resistance cell populations that may serve as new biomarkers of drug response. Notably, they found rare populations carrying the resistance signatures within sensitive cells, suggesting pre-existence of drug resistant populations.

These studies highlight the complexity of tumor genomes and epigenomes captured at the single cell levels is not captured by bulk sequencing and can be important determinants of ITH and drug resistance.

Proteomics and pathology

Tumor classification performed in bulk, either histopathological or genomic categorization, often fails to sufficiently assess patient responsiveness to drugs. For example, breast cancers are classified into the estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) subgroup based on histological staining and predicted to respond well to endocrine therapy. However, nearly 30% of the ER+ breast cancers eventually develop endocrine-resistance and progress to metastasis [35]. To explain this, a study on ER+ breast cancers analyzed about 70 proteins using mass cytometry (CyTOF) across millions of single cells [36]. This study revealed the existence of multiple subgroups of tumor cells in the ER+ cohort that were correlated with differential therapeutic response. Of these subgroups, two were found to express very low ERα, abundant with well-differentiated epithelial cells, while other subgroups were each characterized by a different dominant phenotype. It is possible that these subgroups respond differently to endocrine therapy.

Single-cell proteomics approaches are also being explored to develop predictive algorithm to recommending drug combinations. A new method to optimize drug combinations relied on single-cell mass cytometry (CyTOF) measurement of molecular markers in cancer cells that were expected to show a response to drug treatment [37]. This method estimated subpopulations in the tumor sample after treatment with various candidate drugs and used a nested effects model to determine the minimum number of drugs required to achieve the largest desired response. However, it remains to be seen whether this approach can be translated to clinical solid tumor samples and cases where surface markers for drug response are not well defined.

In addition to single-cell “omic” approaches, latest developments in the field of multiplexed immunofluorescence imaging have enabled simultaneous profiling of multiple proteins in single-cells of pathological specimens. For example, a tissue-based cyclic immunofluorescence (t-CyCIF) approach was used to profile proteins representative of key signaling pathways and immune cells in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, glioblastoma and renal cell carcinomas [38]. Using formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens, this study recapitulated heterogeneity in single-cell phenotypes in archival specimens that were otherwise not possible to detect with other single-cell approaches requiring fresh specimens. Several additional multiplexed imaging platforms have been developed that measure a large number of protein targets in FFPE tumor samples, such as multiplexed fluorescence microscopy (MxIF) [39] multiplexed ion beam imaging (MIBI) [40]. These techniques allow practical assessment of ITH and drug response biomarkers using archival tissue specimens.

Tracking evolution of individual cancers

Clonal evolution is documented in virtually all cancer types [41]. Multiple approaches have been proposed to combat the evolution of drug-resistant states, including targeting driver clonal mutation events, resistant phenotypes, or pro-actively prevent clonal expansion by targeting genome instability or exploiting evolutionary constraints (reviewed in [42]). Compared to single-cell sequencing, clustering of bulk somatic mutations can only provide a low-resolution evolutionary history of tumors that cannot separate low-frequency variants into subclones [43].

These challenges and limitations of reconstructing the evolutionary structure of tumors are being addressed using integrated analyses of the genome, transcriptome and epigenomes of single cells. In theory, scDNA-seq detects SNVs and CNAs in individual cells, thereby detecting rare subclonal variants that maybe missed by bulk sequencing. As a proof-of-concept, an analysis of two colorectal tumors compared scDNA-seq data with exome and targeted deep sequencing to discover rare subclones carrying mutations in key tumor suppressors and oncogenes [44]. The rare subclones were reported to emerge from a completely independent lineage compared to the majority of the primary tumor and continued to evolve in parallel. A subsequent study utilized targeted scDNA-seq to analyze acute myeloid leukemia tumors and compared with bulk sequencing [45]. Interestingly, this study found significant difference in the clonal frequencies determined using bulk sequencing compared to scDNA-seq. High-frequency clones were overestimated in bulk data whereas several low-frequency subclones could only be detected in the single-cell data.

In addition to mutation-based clonal inference, integrated analysis of the evolutionary structure with scRNA-seq data can reveal important information about the phenotypes associated with drug resistance and disease progression [46]. For example, an integrated scRNA-seq, scDNA-seq, and whole-exome sequencing (WES) analysis of chemotherapy response in TNBCs reported that chemotherapy did not increase the overall tumor mutation burden in the bulk somatic genomes [47]. Instead, a diverse set of chemoresistant genotypes that pre-existed in specific subclones were selected in response to chemotherapy. In contrast, subclonal transcriptional heterogeneity was acquired during evolution but ultimately converged onto a few shared phenotypes like epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), AKT1 signaling, and extracellular matrix degradation. Another integrated analysis of scRNA-seq profiles of ER+ breast cancers examined the adaptive phenotypes of resistant subclones inferred from WES data [48]. This study showed an increased mutation rate in post-chemotherapy subclones with APOBEC mutation signatures and activating ABCB1 promoter fusions. Despite the apparent heterogeneity in the subclone variants across the subclones, EMT pathway, receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, and immune surveillance pathways were commonly dysregulated in the resistant subclones, and cells enriched in these pathways responded to targeted therapy in vitro. Single-cell RNA sequencing studies have shown that tumor subclones have a different response to therapy; for example, subclones that express an ABCB1 promoter fusion survive chemotherapy while clones lacking this fusion do not; similarly, cancer subclones with reversions in BRCA mutations preferentially survive platinum-based therapy [48]. Thus, integrated profiling of the evolutionary structure of tumors together with scRNA-seq data provides information about relevant phenotypes for developing therapeutic strategies. This becomes important for cancers with low tumor mutation burden such as acute myeloid leukemia, where acquired CNAs are relatively rare, and subclonal structures and drug resistance phenotypes are difficult to identify without scRNA-seq information [49].

As shown in these studies, single-cell technologies are enabling accurate inference of the evolutionary structures of tumors. They provide new opportunities to tailor treatment decisions that target specific resistance-associated genotypes and phenotypes that evolve in individual cancers.

Diversity of the tumor microenvironment

Single-cell methods have been utilized to gain a detailed picture of the interactions that exist between malignant cells and non-malignant cells in the TME. In one of the first studies of its type, it was discovered that transcriptomic heterogeneity was not just a characteristic feature of the malignant colorectal tumor cell population, but also existed in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) present in the TME [50]. The study found distinct CAF populations could promote tumor progression by secreting the pro-EMT factors like the TGF-β3 ligand and the TGF-β activator protein MMP2. Similar features were reported in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, where CAFs appeared to interact with a subset of the malignant cell population leading to an increased propensity towards the activation of the EMT program [51]. A study of scRNA-seq profiles from breast cancer revealed the existence of at least three distinct subtypes of CAFs, each with unique phenotypes [52]. This study also demonstrated the translational utility of CAF subtypes as independent prognostic biomarkers. Subsequently, certain CAFs in TNBCs were found to promote cancer stem cell plasticity through the activation of the hedgehog signaling pathway [53]. The study demonstrated the clinical benefit of targeted hedgehog signaling inhibition with SMO inhibitors in a phase I trial of chemoresistant TNBCs classified on the presence of specific CAFs.

Perhaps one of the most attractive applications of scRNA-seq in cancer precision medicine has been the characterization of the repertoire and quantity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Immune checkpoint therapy that blocks inhibitors of the immune response against tumor cells, including CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1, have shown promising outcomes in aggressive cancers with otherwise few therapeutic options and may be predicted based on the status of TILs (reviewed in [54,55]). Distinct subpopulations of T-cells and the proportion of TILs were reported in a scRNA-seq analysis of hepatocellular carcinomas that correlated with immune checkpoint inhibitor response and patient outcomes [56]. Deep scRNA-seq analysis of the T-cell repertoire of non-small cell lung cancers revealed extensive heterogeneity [57]. They found two CD8+ T-cell clusters that were predictive of T-cell exhaustion associated with poor immunotherapy response and patient outcomes. The CD8+ clusters along with the activated tumor Treg cells identified in this study could serve as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinomas. Similar prognostic T-cell subpopulations were identified in scRNA-seq analyses of the breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancers [58–60].

Recent studies have extended the analysis of immune cell heterogeneity to the myeloid-derived population in the TME. Single-cell mass cytometry analysis of melanoma cells revealed that the frequency of classical monocytes was predictive of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy response [61]. Heterogenous tumor-infiltrating myeloid cell populations that interact and promote tumor growth and proliferation have been reported in lung and colon cancers [62,63]. In ER+ breast cancers, a mass cytometry analysis found a correlation between the frequency of ERα+ cells in the tumors and PD-L1+ tumor-associated macrophages in the ER+ tumors. While ER+ tumors generally do not show a response to immunotherapy, this observation suggests that a subset of ER+ breast cancers may actually benefit from anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy [36].

While still in the early stages, these studies using single-cell technologies present compelling opportunities for precision diagnosis and personalized therapy that target the components of the TME.

New mechanisms of drug resistance

Single-cell technologies are enabling the detection and characterization of rare cell populations that exist in a transient drug-resistant state that are very challenging to detect using bulk molecular profiling. A recent study utilized single-cell RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization to track the presence of drug resistance transcripts in melanoma and other cell lines [64]. In this highly sensitive screen, they found resistant transcripts were transiently expressed in a very small fraction of the cells prior to treatment. These resistance transcripts were elevated in post-therapy resistant cells. However, the expression of these resistance transcripts reverted to basal levels after removal of the drug perturbation, even though the cells remained resistant. To better understand the role of transient non-genetic heterogeneity on drug response, a recent study presented a method to investigate the single-cell transcriptomes of the same cell tested across multiple pharmacological screens [65]. This approach, called fate-seq, enables the estimation of the single-cell transcriptomic profiles of cancer cells prior to drug-induced changes in the transcriptome. This method can reveal transient cell states that are predictive of drug response that likely exists only for a short duration of time. Thus, these single-cell studies captured a rare phenomenon that is not possible to detect with bulk omic approaches.

Single-cell methods are also being integrated into large-scale pharmacological and forward genetic screens to simultaneously detect the association between genetic and phenotypic diversity and drug response. These efforts leverage new approaches that permit the simultaneous profiling of multiplexed cells in a single sequencing run, thereby reducing the prohibitive cost associated with large-scale screens [66]. The method deconvolutes sample identity by modeling the distribution of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in each cell. Extending this approach, a study developed a multiplexed scRNA-seq assay where diverse samples were labeled by a simple transfection with short oligonucleotide barcodes [67]. This approach enabled simultaneously study the scRNA transcriptomes of cancer cell lines in a pharmacological screen for multiple drugs. Multiplexing scRNA-seq assays were also combined with CRISPR-based genetic perturbation screens to simultaneously study the effects of pharmacological and genetic perturbations on transcriptomic heterogeneity [68]. These principles were adapted in a study to perform a scRNA-seq analysis of CRISPR and drug perturbations on a mixed population of 24 to 99 cell lines [69]. In addition to cost-effectiveness, these approaches could be extended to create large-scale drug screens at a single-cell resolution and provide opportunities to develop new single-cell biomarkers of drug response.

Concluding remarks

The rapid development of single-cell technologies and complementary computational modeling approaches is enabling the characterization of tumor heterogeneity, subclonal evolution, and the discovery of novel drug resistance mechanisms at a resolution that was previously not possible with bulk techniques.

It is now possible to develop adaptive therapeutic strategies beyond actionable mutations against resistant phenotypes that emerge in drug-resistant subpopulations. Moreover, characterization of the genetic and non-genetic drivers of acquired therapeutic resistance may enable the development of new strategies with the goal of proactively preventing the evolution of resistant states. As tumors undergo evolution under the selection pressure of therapy, it is important that single-cell events at the genetic and non-genetic levels are temporally characterized in order to account for genomic changes. This task requires the longitudinal acquisition of patient samples that may not always be feasible. However, improved sensitivity of the single-cell technologies is enabling the utilization of circulating tumor cells to uncover the heterogeneity and evolution of the tumors using non-invasive approaches. Finally, methods combining forward genetic screens with single-cell profiling of cancer cell line drug-screens are enabling rapid pharmacogenomic profiling in pre-clinical models. The data from single-cell analyses of the tumor and its microenvironment also have the potential to provide unique insights about tumor biology, especially in the absence of obvious genetic events that are acquired over the course of cancer. Consequently, new theoretical approaches must be incorporated in modeling the biology and evolution of a tumor.

The implementation of single-cell technologies in the clinic will require overcoming key considerations (see Outstanding Questions). The implementation of single-cell technologies from discovery research to a clinical application phase depends on overcoming key technical challenges that are commonly shared across single-cell platforms (reviewed in [70]). Continued advancement in techniques to acquire single-cell data is addressing technical challenges such as data sparsity due to dropouts in single-cell sequencing, and low detection limits in mass cytometry. In the meantime, computational approaches to reliably impute missing data may help alleviate the issues with sparsity [71]. With the growth of data being generated from single-cell techniques, there will also be a growing need for standardized data processing and analytical pipelines for handling data from diverse sites and sources. Thus, it is important to ensure that single-cell data is properly normalized and appropriately adjusted to account for batch-effects for a fair comparison across experiments [72,73]. In addition, new methods are required that allow integrated investigation of data from different sources, which is at the genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic levels from the sample tumor sample, and perhaps from the same cell. We anticipate that the number of computational methods to assess tumor cell diversity, heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and predictive models will continue to grow at a rapid pace in the near future. Considering the exciting translational potential in clinical oncology, these studies should be supported with exhaustive evidence, along with transparent data and code sharing.

Outstanding Questions.

How can we implement single-cell technologies into clinical practice?

How do we overcome sparsity in single-cell data?

How can we compare and consolidate information from single-cell experimental batches and independent studies?

How do we perform exhaustive validation of key findings from pioneering, but one-off, studies?

Highlights.

Advancing towards the next generation in cancer precision medicine will require incorporation of the effects of tumor heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and microenvironment on drug resistance and patient outcomes.

Single-cell technologies are enabling separation and characterization of molecular signals from heterogeneous populations of malignant and non-malignant cells.

New biomarkers and therapeutic strategies can be developed against resistant subclonal genotypes and phenotypes determined at a high resolution with single-cell approaches.

Novel mechanisms of drug resistance are being discovered by combining single-cell data with forward genetics and large-scale pharmacological screens

Single-cell strategies are being adopted in the clinic to predict response to immune therapy, targeted drugs and study tumor evolution using non-invasive techniques

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a National Cancer Institute U54 grant (U54CA209978). Figure 1, Key Figure was created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bray F et al. (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 68, 394–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nath A et al. (2017) Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics of Targeted Therapeutics in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Mol Diagn Ther 21, 621–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janku F et al. (2010) Targeted therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer—is it becoming a reality? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 7, 401–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Incorvati JA et al. (2013) Targeted therapy for HER2 positive breast cancer. J Hematol Oncol 6, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis C et al. (2012) The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 486, 346–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marisa L et al. (2013) Gene Expression Classification of Colon Cancer into Molecular Subtypes: Characterization, Validation, and Prognostic Value. PLoS Med 10, e1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadanandam A et al. (2013) A colorectal cancer classification system that associates cellular phenotype and responses to therapy. Nat Med 19, 619–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markert EK et al. (2011) Molecular classification of prostate cancer using curated expression signatures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 21276–21281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou J et al. (2010) Gene Expression-Based Classification of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas and Survival Prediction. PLoS ONE 5, e10312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cejalvo JM et al. (2017) Intrinsic Subtypes and Gene Expression Profiles in Primary and Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 77, 2213–2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sparano JA et al. (2018) Adjuvant Chemotherapy Guided by a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 379, 111–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardoso F et al. (2016) 70-Gene Signature as an Aid to Treatment Decisions in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 375, 717–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhaak RGW et al. (2010) Integrated Genomic Analysis Identifies Clinically Relevant Subtypes of Glioblastoma Characterized by Abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 17, 98–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel AP et al. (2014) Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science 344, 1396–1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q et al. (2017) Tumor Evolution of Glioma-Intrinsic Gene Expression Subtypes Associates with Immunological Changes in the Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 32, 42–56.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neftel C et al. (2019) An Integrative Model of Cellular States, Plasticity, and Genetics for Glioblastoma. Cell 178, 835–849.e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eyler CE et al. (2020) Single-cell lineage analysis reveals genetic and epigenetic interplay in glioblastoma drug resistance. Genome Biol 21, 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karaayvaz M et al. (2018) Unravelling subclonal heterogeneity and aggressive disease states in TNBC through single-cell RNA-seq. Nat Commun 9, 3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage P et al. (2017) A Targetable EGFR-Dependent Tumor-Initiating Program in Breast Cancer. Cell Reports 21, 1140–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K-T et al. (2015) Single-cell mRNA sequencing identifies subclonal heterogeneity in anti-cancer drug responses of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Genome Biol 16, 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roider T et al. (2020) Dissecting intratumour heterogeneity of nodal B-cell lymphomas at the transcriptional, genetic and drug-response levels. Nat Cell Biol 22, 896–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim SB et al. (2019) Addressing cellular heterogeneity in tumor and circulation for refined prognostication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116, 17957–17962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart CA et al. (2020) Single-cell analyses reveal increased intratumoral heterogeneity after the onset of therapy resistance in small-cell lung cancer. Nat Cancer 1, 423–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths JI et al. (2020) Circulating immune cell phenotype dynamics reflect the strength of tumor–immune cell interactions in patients during immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 16072–16082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim K-T et al. (2016) Application of single-cell RNA sequencing in optimizing a combinatorial therapeutic strategy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Genome Biol 17, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng G et al. (2014) Single cell mutational analysis of PIK3CA in circulating tumor cells and metastases in breast cancer reveals heterogeneity, discordance, and mutation persistence in cultured disseminated tumor cells from bone marrow. BMC Cancer 14, 456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werner-Klein M et al. (2020) Interleukin-6 trans-signaling is a candidate mechanism to drive progression of human DCCs during clinical latency. Nat Commun 11, 4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw JA et al. (2017) Mutation Analysis of Cell-Free DNA and Single Circulating Tumor Cells in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients with High Circulating Tumor Cell Counts. Clin Cancer Res 23, 88–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mangano C et al. (2019) Precise detection of genomic imbalances at single-cell resolution reveals intra-patient heterogeneity in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 9, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L et al. (2019) Single-cell whole-genome sequencing reveals the functional landscape of somatic mutations in B lymphocytes across the human lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116, 9014–9019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brazhnik K et al. (2020) Single-cell analysis reveals different age-related somatic mutation profiles between stem and differentiated cells in human liver. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Litzenburger UM et al. (2017) Single-cell epigenomic variability reveals functional cancer heterogeneity. Genome Biol 18, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pixberg CF et al. (2017) Analysis of DNA methylation in single circulating tumor cells. Oncogene 36, 3223–3231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grosselin K et al. (2019) High-throughput single-cell ChIP-seq identifies heterogeneity of chromatin states in breast cancer. Nat Genet 51, 1060–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinert T and Barrios CH (2015) Optimal management of hormone receptor positive metastatic breast cancer in 2016. Ther Adv Med Oncol 7, 304–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner J et al. (2019) A Single-Cell Atlas of the Tumor and Immune Ecosystem of Human Breast Cancer. Cell 177, 1330–1345.e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anchang B et al. (2018) DRUG-NEM: Optimizing drug combinations using single-cell perturbation response to account for intratumoral heterogeneity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115, E4294–E4303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin J-R et al. (2018) Highly multiplexed immunofluorescence imaging of human tissues and tumors using t-CyCIF and conventional optical microscopes. eLife 7, e31657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerdes MJ (2013) Highly multiplexed single-cell analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cancer tissue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 11982–11987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angelo M et al. (2014) Multiplexed ion beam imaging of human breast tumors. Nat Med 20, 436–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greaves M and Maley CC (2012) Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature 481, 306–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGranahan N and Swanton C (2017) Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell 168, 613–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuipers J et al. (2017) Advances in understanding tumour evolution through single-cell sequencing. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1867, 127–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung ML et al. (2017) Single-cell DNA sequencing reveals a late-dissemination model in metastatic colorectal cancer. Genome Res. 27, 1287–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pellegrino M et al. (2018) High-throughput single-cell DNA sequencing of acute myeloid leukemia tumors with droplet microfluidics. Genome Res. 28, 1345–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McQuerry JA et al. (2017) Mechanisms and clinical implications of tumor heterogeneity and convergence on recurrent phenotypes. J Mol Med 95, 1167–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim C et al. (2018) Chemoresistance Evolution in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Delineated by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell 173, 879–893.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brady SW et al. (2017) Combating subclonal evolution of resistant cancer phenotypes. Nat Commun 8, 1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petti AA et al. (2019) A general approach for detecting expressed mutations in AML cells using single cell RNA-sequencing. Nat Commun 10, 3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H et al. (2017) Reference component analysis of single-cell transcriptomes elucidates cellular heterogeneity in human colorectal tumors. Nat Genet 49, 708–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Puram SV et al. (2017) Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Primary and Metastatic Tumor Ecosystems in Head and Neck Cancer. Cell 171, 1611–1624.e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartoschek M et al. (2018) Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun 9, 5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cazet AS et al. (2018) Targeting stromal remodeling and cancer stem cell plasticity overcomes chemoresistance in triple negative breast cancer. Nat Commun 9, 2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma P and Allison JP (2015) Immune Checkpoint Targeting in Cancer Therapy: Toward Combination Strategies with Curative Potential. Cell 161, 205–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waldman AD et al. (2020) A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol DOI: 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng C et al. (2017) Landscape of Infiltrating T Cells in Liver Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell 169, 1342–1356.e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo X et al. (2018) Global characterization of T cells in non-small-cell lung cancer by single-cell sequencing. Nat Med 24, 978–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Azizi E et al. (2018) Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell 174, 1293–1308.e36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer (kConFab) et al. (2018) Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nat Med 24, 986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scheper W et al. (2019) Low and variable tumor reactivity of the intratumoral TCR repertoire in human cancers. Nat Med 25, 89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krieg C et al. (2018) High-dimensional single-cell analysis predicts response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat Med 24, 144–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang L et al. (2020) Single-Cell Analyses Inform Mechanisms of Myeloid-Targeted Therapies in Colon Cancer. Cell 181, 442–459.e29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zilionis R et al. (2019) Single-Cell Transcriptomics of Human and Mouse Lung Cancers Reveals Conserved Myeloid Populations across Individuals and Species. Immunity 50, 1317–1334.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaffer SM et al. (2017) Rare cell variability and drug-induced reprogramming as a mode of cancer drug resistance. Nature 546, 431–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyer M et al. (2020) Profiling the Non-genetic Origins of Cancer Drug Resistance with a Single-Cell Functional Genomics Approach Using Predictive Cell Dynamics. Cell Systems DOI: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang HM et al. (2018) Multiplexed droplet single-cell RNA-sequencing using natural genetic variation. Nat Biotechnol 36, 89–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shin D et al. (2019) Multiplexed single-cell RNA-seq via transient barcoding for simultaneous expression profiling of various drug perturbations. Sci. Adv 5, eaav2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dixit A et al. (2016) Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 167, 1853–1866.e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McFarland JM et al. (2020) Multiplexed single-cell transcriptional response profiling to define cancer vulnerabilities and therapeutic mechanism of action. Nat Commun 11, 4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lähnemann D et al. (2020) Eleven grand challenges in single-cell data science. Genome Biol 21, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hicks SC et al. (2018) Missing data and technical variability in single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments. Biostatistics 19, 562–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cole MB et al. (2019) Performance Assessment and Selection of Normalization Procedures for Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Cell Systems 8, 315–328.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tran HTN et al. (2020) A benchmark of batch-effect correction methods for single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol 21, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al. (2013) The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet 45, 1113–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.The International Cancer Genome Consortium (2010) International network of cancer genome projects. Nature 464, 993–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gao H et al. (2015) High-throughput screening using patient-derived tumor xenografts to predict clinical trial drug response. Nat Med 21, 1318–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghandi M et al. (2019) Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 569, 503–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nath A et al. (2019) Discovering long noncoding RNA predictors of anticancer drug sensitivity beyond protein-coding genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116, 22020–22029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.AstraZeneca-Sanger Drug Combination DREAM Consortium et al. (2019) Community assessment to advance computational prediction of cancer drug combinations in a pharmacogenomic screen. Nat Commun 10, 2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Geeleher P et al. (2017) Discovering novel pharmacogenomic biomarkers by imputing drug response in cancer patients from large genomics studies. Genome Res. 27, 1743–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iorio F et al. (2016) A Landscape of Pharmacogenomic Interactions in Cancer. Cell 166, 740–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seashore-Ludlow B et al. (2015) Harnessing Connectivity in a Large-Scale Small-Molecule Sensitivity Dataset. Cancer Discov 5, 1210–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roma-Rodrigues C et al. (2019) Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. IJMS 20, 840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rhee J-K et al. (2018) Impact of Tumor Purity on Immune Gene Expression and Clustering Analyses across Multiple Cancer Types. Cancer Immunol Res 6, 87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aran D et al. (2015) Systematic pan-cancer analysis of tumour purity. Nat Commun 6, 8971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dagogo-Jack I and Shaw AT (2018) Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15, 81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herrera-Abreu MT et al. (2016) Early Adaptation and Acquired Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibition in Estrogen Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 76, 2301–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Martin L-A et al. (2017) Discovery of naturally occurring ESR1 mutations in breast cancer cell lines modelling endocrine resistance. Nat Commun 8, 1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Musgrove EA and Sutherland RL (2009) Biological determinants of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 9, 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dentro SC et al. (2017) Principles of Reconstructing the Subclonal Architecture of Cancers. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7, a026625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gruber M et al. (2019) Growth dynamics in naturally progressing chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature 570, 474–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Turajlic S et al. (2018) Deterministic Evolutionary Trajectories Influence Primary Tumor Growth: TRACERx Renal. Cell 173, 595–610.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Parikh AR et al. (2019) Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting acquired resistance and tumor heterogeneity in gastrointestinal cancers. Nat Med 25, 1415–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rothwell DG et al. (2019) Utility of ctDNA to support patient selection for early phase clinical trials: the TARGET study. Nat Med 25, 738–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Flavahan WA et al. (2017) Epigenetic plasticity and the hallmarks of cancer. Science 357, eaal2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Le Magnen C et al. (2018) Lineage Plasticity in Cancer Progression and Treatment. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol 2, 271–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ben-David U et al. (2018) Genetic and transcriptional evolution alters cancer cell line drug response. Nature 560, 325–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hu P et al. (2016) Single Cell Isolation and Analysis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 4,[dummy_incomplete para] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zong C et al. (2012) Genome-Wide Detection of Single-Nucleotide and Copy-Number Variations of a Single Human Cell. Science 338, 1622–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spits C et al. (2006) Whole-genome multiple displacement amplification from single cells. Nat Protoc 1, 1965–1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mallory XF et al. (2020) Methods for copy number aberration detection from single-cell DNA-sequencing data. Genome Biol 21, 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tarabichi M et al. (2021) A practical guide to cancer subclonal reconstruction from DNA sequencing. Nat Methods DOI: 10.1038/s41592-020-01013-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ramsköld D et al. (2012) Full-length mRNA-Seq from single-cell levels of RNA and individual circulating tumor cells. Nat Biotechnol 30, 777–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zheng GXY et al. (2017) Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat Commun 8, 14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hashimshony T et al. (2012) CEL-Seq: Single-Cell RNA-Seq by Multiplexed Linear Amplification. Cell Reports 2, 666–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sasagawa Y et al. (2013) Quartz-Seq: a highly reproducible and sensitive single-cell RNA sequencing method, reveals non-genetic gene-expression heterogeneity. Genome Biol 14, 3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Macosko EZ et al. (2015) Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun S et al. (2019) Accuracy, robustness and scalability of dimensionality reduction methods for single-cell RNA-seq analysis. Genome Biol 20, 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Abdelaal T et al. (2019) A comparison of automatic cell identification methods for single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol 20, 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Saelens W et al. (2019) A comparison of single-cell trajectory inference methods. Nat Biotechnol 37, 547–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang T et al. (2019) Comparative analysis of differential gene expression analysis tools for single-cell RNA sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 20, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hänzelmann S et al. (2013) GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Aibar S et al. (2017) SCENIC: single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat Methods 14, 1083–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Luecken MD and Theis FJ (2019) Current best practices in single‐cell RNA‐seq analysis: a tutorial. Mol Syst Biol 15, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Farlik M et al. (2015) Single-Cell DNA Methylome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Inference of Epigenomic Cell-State Dynamics. Cell Reports 10, 1386–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Guo H et al. (2013) Single-cell methylome landscapes of mouse embryonic stem cells and early embryos analyzed using reduced representation bisulfite sequencing. Genome Research 23, 2126–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Buenrostro JD et al. (2015) Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature 523, 486–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nagano T et al. (2013) Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature 502, 59–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rotem A et al. (2015) Single-cell ChIP-seq reveals cell subpopulations defined by chromatin state. Nat Biotechnol 33, 1165–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shema E et al. (2019) Single-cell and single-molecule epigenomics to uncover genome regulation at unprecedented resolution. Nat Genet 51, 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Clark SJ et al. (2016) Single-cell epigenomics: powerful new methods for understanding gene regulation and cell identity. Genome Biol 17, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bendall SC et al. (2011) Single-Cell Mass Cytometry of Differential Immune and Drug Responses Across a Human Hematopoietic Continuum. Science 332, 687–69621551058 [Google Scholar]

- 123.Budnik B et al. (2018) SCoPE-MS: mass spectrometry of single mammalian cells quantifies proteome heterogeneity during cell differentiation. Genome Biol 19, 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zenobi R (2013) Single-Cell Metabolomics: Analytical and Biological Perspectives. Science 342, 1243259–1243259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Labib M and Kelley SO (2020) Single-cell analysis targeting the proteome. Nat Rev Chem 4, 143–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Goltsev Y et al. (2018) Deep Profiling of Mouse Splenic Architecture with CODEX Multiplexed Imaging. Cell 174, 968–981.e15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Stoeckius M et al. (2017) Simultaneous epitope and transcriptome measurement in single cells. Nat Methods 14, 865–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Macaulay IC et al. (2015) G&T-seq: parallel sequencing of single-cell genomes and transcriptomes. Nat Methods 12, 519–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Liu L et al. (2019) Deconvolution of single-cell multi-omics layers reveals regulatory heterogeneity. Nat Commun 10, 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]