Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the status of mismatch repair (MMR) and microsatellite instability (MSI) in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and to examine correlations between MMR/MSI status and clinicopathological parameters.

Methods

We retrospectively collected tissue samples from 440 patients with TNBC and constructed tissue microarrays. Protein expression of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC). We also analyzed 195 patient samples using MSI polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. Correlations between MSI status and clinicopathological parameters and prognosis were analyzed.

Results

The median age of the cohort was 49 years (range: 24–90 years) with a median follow-up period of 68 months (range: 1–170 months). All samples were positive for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, except for one sample identified as MMR-deficient (dMMR) by IHC, with loss of MSH2 and intact MSH6 expression. MSI PCR revealed no case with high-frequency MSI (MSI-H), whereas 14 (7.2%) and 181 (92.8%) samples demonstrated low-frequency and absence of MSI events, respectively. The dMMR sample harbored low-frequency instability, as revealed by MSI PCR, and a possible EPCAM deletion in the tumor, as observed from next-generation sequencing. No correlations were detected between MMR or MSI status and clinicopathological parameters, programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, or survival.

Conclusions

The incidence of dMMR/MSI-H is extremely low in TNBC, and rare discordant MSI PCR/MMR IHC results may be encountered. Moreover, MMR/MSI status may be of limited prognostic value. Further studies are warranted to explore other predictive immunotherapy biomarkers for TNBC.

Keywords: triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency, microsatellite instability, prognosis, mismatch repair proficiency

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is characterized by poor prognosis and lack of effective targeted therapies. Most TNBCs are rich in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), the presence of which correlates with tumor immune response activation and sensitivity to chemotherapy, suggestive of better overall survival (1). Immunotherapy has become an indispensable treatment strategy for cancer, as it has shown effective results across several solid tumors. Inhibition of the T-cell inhibitory molecule programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) has been proven clinically effective in the treatment of multiple cancers (2). In breast cancer, PD-L1 levels are correlated with TIL levels and the complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore, PD-L1 can be used as a biomarker to identify patients who could benefit from immunotherapy (3). However, no efficient immunotherapy biomarkers are known for TNBC. PD-L1 was initially regarded as an efficient biomarker to predict the efficacy of immunotherapy, however, our previous study revealed that its expression is very low in TNBC tumors, specifically in Chinese women (4). Thus, it is important to identify novel immunotherapy biomarkers for TNBC.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is caused by defective DNA mismatch repair (dMMR) genes and is characterized by a decrease or increase in repeated nucleotide sequences, which can lead to evasion of apoptosis, development of malignant mutations, and tumorigenesis (5, 6). MSI is a marker of dMMR. MSI status can be determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and next-generation sequencing (NGS) (6). Generally, the PCR and NGS methods divide tumors into high-frequency MSI (MSI-H), low-frequency MSI (MSI-L), or microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors (7). dMMR and MSI-H have been found in various tumors, such as uterine, ovarian, colorectal, small intestinal, stomach, urothelial, central nervous system, and adrenal gland tumors (8, 9). Germline pathogenic mutations in the DNA mismatch repair genes are also the hallmarks of Lynch syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder associated with a genetic predisposition for developing a wide spectrum of cancers. Both dMMR and MSI-H have been demonstrated as effective predictors of immunotherapy response (10, 11), and have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as biomarkers for the treatment of solid tumors with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed death 1 (PD-1), regardless of tumor origin (12).

dMMR/MSI-H have also been evaluated as potential prognosticators and therapeutic targets in several cancers. However, the prognostic value of these biomarkers varies between tumor types. For example, dMMR/MSI-H has been associated with poor prognosis in individuals with colorectal cancer that was insensitive to 5-fluorouracil (FU)-based adjuvant chemotherapy (13), while dMMR/MSI-H were associated with good prognosis in gastric cancer (14). For this reason, MMR/MSI status has been screened in a variety of tumors. Approximately 15% of colon tumors and 15–31% of uterine tumors are MSI-H (15, 16). For hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic and non-virally infected livers, 16% of tumors (from 37 patients) were MSI-H (17). In a meta-analysis of 48 studies describing 18,612 patients with gastric cancer, MSI-H was observed in 9.2% of patients (14). The prevalence of dMMR/MSI-H in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) varied greatly between different subject cohorts, ranging from 0% to 22% (18, 19).

However, data on the prevalence and the prognostic significance of dMMR/MSI-H in breast cancer is limited, especially for TNBC. Although there have been studies on MMR/MSI status in breast cancer, the number of cases is often small, with the largest cohort comprising 444 patients, only 23 of which were TNBC (20). The proportion of MSI-H in these groups varied largely, from 0.2% to 18.6% (20, 21). Most of the available studies used only a single method to evaluate the MMR/MSI status. Furthermore, estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative cases were mixed. Several studies have shown that dMMR/MSI-H correlates with resistance to chemotherapy and poor prognosis, while other studies reported that patients with dMMR/MSI-H lived longer than ER-negative breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy (20, 22–24). Therefore, further verification of the relationship between MMR/MSI status and prognosis is needed. In this study, we enrolled 440 patients with TNBC to investigate MMR/MSI status at both protein and nucleic acid level. We further evaluated the prognostic role of MMR/MSI status and its potential correlations with clinicopathological features, including PD1/PD-L1 expression.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples and Follow-Up Information

440 patients with unilateral TNBC undergoing breast surgery were enrolled, and their FFPE tissues were collected. All patients had been diagnosed at Peking Union Medical College Hospital from May, 2002 to December, 2014, and received standard treatments according to established protocols, including curative surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Primary Tumor/Regional Lymph Nodes/Distant Metastasis (TNM) stage was classified according to the AJCC 8th edition. Those treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and those who provided insufficient tissue samples were excluded. Patients with stage IV breast cancer either received neoadjuvant therapy or provided biopsy specimens only, thus there were no stage IV cases in our cohort. Two pathologists independently evaluated the appropriate tumor sections. 195 consecutive cases between May, 2002 and December, 2010 were subjected to both PCR and immunohistochemistry analyses. The rest of consecutive cases between January, 2011 and December, 2014 in the cohort were subjected to IHC analysis only. Patients with MSI-H or dMMR status were further subjected to next-generation sequencing to identify the cause of their defective mismatch repair mechanism.

The follow-up period for this retrospective study was from the date of surgery to March 31st, 2019. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to the time of death due to any reason. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to the first relapse of the disease (local, regional, or distant metastasis, or contralateral breast cancer). Disease recurrence and metastases were confirmed by diagnostic imaging and pathology.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by Peking Union Medical College Hospital Institutional Review Board (PUMCH IRB). All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee, as well as the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent of written form was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Tissue Microarray Preparation and Pathological Analysis

A Quick-Ray Manual Tissue Microarrayer (UT-06, UNITMA) was used to construct the tissue microarrays. Three 1-mm cores per case were obtained with a needle and arrayed in a recipient block. Two pathologists assessed the pathological parameters of each sample, including histological differentiation, lympho-vascular invasion, and TILs. TILs evaluation was carried out according to the methods described previously (25). Pathological staging was performed according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s TNM staging system (26).

Immunohistochemistry

The expression of MMR proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 was detected by immunohistochemistry on an FFPE tissue microarray using Ventana Benchmark XT autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Antibody information and respective optimizations are listed in Table 1 . Absence of nuclear staining in tumor cells was considered “loss of expression” with intervening stromal positivity serving as an internal control. ER, PR, and HER2 status were assessed based on the ASCO/CAP guidelines (27). TNBC was defined as HER2 negativity and ER and PR nuclear staining in <1% of the tumor cells. HER2 negativity was determined by either negative (0 or 1) or equivocal (2+) HER2 staining by IHC and no HER2 gene amplification revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. The expression of ER, PR, HER2, P53, proliferation marker Ki-67 and basal-like markers (cytokeratin 5/6, extracellular growth factor receptor/EGFR, cytokeratin 14), was detected at the time of diagnosis. Basal-like phenotype of TNBC was defined by positivity for any of the three basal-like markers in the present study. PD-L1 and PD-1 were evaluated as previously described (4).

Table 1.

Antibody and IHC information for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.

| Antibody | Clone | Dilution | Source | Positive style | Antigen Retrieval* | Incubation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLH1 | Mouse Monoclonal (M1) |

Prediluted | Ventana | Nuclear staining | 95°C, 88min | 36°C, 16min | ||

| PMS2 | Mouse Monoclonal (A16-4) |

Prediluted | Ventana | Nuclear staining | 95°C, 92min | 36°C, 6min | ||

| MSH2 | Rabbit Monoclonal (G219-1129) |

Prediluted | Ventana | Nuclear staining | 95°C, 88min | 36°C, 32min | ||

| MSH6 | Rabbit Monoclonal (SP93) |

Prediluted | Ventana | Nuclear staining | 95°, 88min | 36°C, 16min | ||

IHC, Immunohistochemistry.

*Heat-induced Antigen Retrieval by 1 mM EDTA in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH8.5).

DNA Extraction and Microsatellite Instability Scoring

DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue samples using the QIAamp DNA Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. MSI analysis was performed on six mononucleotide repeat markers (BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, NR-27, and MONO-27; Table 2 ) using a Microsatellite Instability Detection Kit (Microread Gene Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China). To detect potential specimen contamination, pentanucleotide repeat markers (Penta C and Penta D) and a sex locus marker (amelogenin) were also analyzed for background confirmation. Fluorescently labeled primers were used in the PCR assay, and results were analyzed on an ABI 3130XL gene analyzer with the GeneScan 3.7 analysis software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). Samples were considered MSI-H when two or more of the markers displayed MSI. Samples with MSI at only one marker were considered MSI-L, and those with no MSI were considered MSS.

Table 2.

Markers and primers of mononucleotide repeat marker analysis.

| Marker | Gene | Primer sequence (5’-3’) | GenBank number |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAT-25 | c-kit | F: TCGCCTCCAAGAATGTAAGT R: TCTGCATTTTAACTATGGCTC |

L04143 |

| Bat-26 | MSH2 | F: TGACTACTTTTGACTTCAGCC R: AACCATTCAACATTTTTAACCC |

U41210 |

| NR-21 | SLC7A8 | F: GAGTCGCTGGCACAGTTCTA R: CTGGTCACTCGCGTTTAGAA |

XM_033393 |

| NR-24 | Zinc finger 2 | F: GCTGAATTTTACCTCCTGAC R: ATTGTGCCATTGCATTCCAA |

X60152 |

| NR-27 | Inhibitor of apoptosis protein-1 | F: AACCATGCTTGCAAACCACT R: CGATAATACTAGCAATGACC |

AF070674 85.1 |

| MONO-27 | M4P4K3 | F: CAGGGAAATGGTGGGAACCCAG R: GTTGGCCAAGTGAAATTTGATC |

AC007684 |

Next-Generation Sequencing

Hybrid capture-based targeted next-generation sequencing was performed. Paired tumor and blood tissue DNA samples were extracted from FFPE samples. Barcoded libraries were hybridized to a multiple-gene panel covering whole exons and selected introns of MMR-related genes, including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM. These libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform and assessed for variants including single nucleotide variants, small insertions and deletions (indels), copy number alterations, and gene fusions/rearrangements. The average sequencing depth for target regions of tumor samples was 8991×, and 97.0% of the average coverage for targeted regions was >1250×.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Qualitative variables were compared by a chi-square test. Survival curves were prepared according to the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. p-values < 0.05 in two-tailed tests were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathological Characteristics

The median age of the cohort was 49 (range: 24–90). Of the 440 patients enrolled, 376 (85.5%) and 136 (30.9%) had received chemotherapy and radiotherapy, respectively. Breast-conserving surgery was conducted for 52 (11.8%) patients, while the rest underwent radical mastectomy. Basal-like breast cancer was detected in 362 (82.3%) patients with TNBC. Other parameters were also evaluated, such as age, tumor size, P53, Ki-67 index, lymph node metastasis, presence of TILs, and expression of immune checkpoint markers, including PD-1 and PD-L1 ( Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients.

| Clinicopathological criteria | No. of patients | Patients with recurrence | Patients without recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| ≤49 | 212 | 67 | 145 |

| >49 | 228 | 71 | 157 |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Pre-menopause | 224 | 73 | 151 |

| Post-menopause | 216 | 65 | 151 |

| Histological grade | |||

| I | 10 | 2 | 8 |

| II | 122 | 40 | 82 |

| III | 308 | 96 | 212 |

| Tumor size | |||

| pT1 | 199 | 50 | 149 |

| pT2 | 219 | 75 | 144 |

| pT3 | 18 | 12 | 6 |

| pT4 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Nodal status | |||

| negative | 247 | 54 | 193 |

| 1–3 nodes | 104 | 32 | 72 |

| 4–9 nodes | 38 | 16 | 22 |

| ≥10 nodes | 51 | 36 | 15 |

| TNM Stage | |||

| I | 135 | 25 | 110 |

| II | 211 | 59 | 152 |

| III | 94 | 54 | 40 |

| Surgical procedure | |||

| Mastectomy | 388 | 119 | 269 |

| Breast conserving | 52 | 19 | 33 |

| Basal-like phenotype | |||

| Negative | 78 | 25 | 53 |

| Positive | 362 | 113 | 249 |

| Ki67 index | |||

| ≤14 | 54 | 24 | 30 |

| >14 | 386 | 114 | 272 |

| TILs | |||

| Low | 330 | 121 | 209 |

| High | 110 | 17 | 93 |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Negative | 56 | 17 | 39 |

| Positive | 376 | 119 | 257 |

| Unknown | 8 | 2 | 6 |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| Negative | 291 | 83 | 208 |

| Positive | 136 | 48 | 88 |

| Unknown | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| MSI | |||

| MSI-L | 14 | 6 | 8 |

| MSS | 177 | 73 | 104 |

| Unknown | 249 | 59 | 190 |

| PD-1 (1%) | |||

| Negative | 59 | 36 | 23 |

| Positive | 136 | 44 | 92 |

| Unknown | 245 | 58 | 187 |

| PD-L1 (25%) | |||

| Negative | 182 | 74 | 108 |

| Positive | 13 | 6 | 7 |

| Unknown | 245 | 58 | 187 |

TNM, Primary Tumor/Regional Lymph Nodes/Distant Metastasis; TILs, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSI-L, low-frequency microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; *Ki-67 index threshold of 14% was chosen according to the St. Gallen Consensus 2013.

The median follow-up period was 96 months (range: 2–184 months), with median DFS and OS values of 88 and 96 months, respectively. During the follow-up, there were 138 (31.4%) deaths and 91 (20.7%) cases of recurrence, with 124 (89.9%) and 73 (80.2%) occurring within the first 5 years.

Mismatch Repair Deficient/High-Frequency Microsatellite Instability Testing

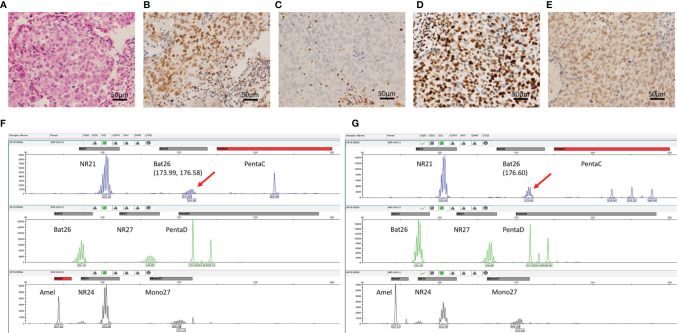

MMR proteins, including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, were detected in the 440 samples by IHC. MMR protein expression analysis revealed mostly proficient MMR (pMMR) phenotypes. Only one case exhibited loss of MSH2 expression ( Figures 1A–E ), suggestive of a dMMR phenotype. A total of 195 samples of TNBC, including the dMMR sample, were further analyzed for MSI through PCR testing. No MSI-H samples were identified ( Figures 1F, G ), while 14 (7.2%) MSI-L and 181 (92.8%) MSS cases were observed. The dMMR case without MSH2 expression as determined by IHC was categorized as MSI-L by PCR analysis.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry for MMR and MSI PCR analysis. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining; (B) MLH1 staining showed positive nuclei. (C) MSH2 staining showed unstained tumor cell nuclei with positively-stained nuclei of stromal cells as normal control. (D, E) The high protein expression of PMS2 and MSH-6, respectively. (F, G) Graphical maps of the gene loci identified in the DNA sequence of paired tumor and normal tissue samples of the MSI-L case with the mutation loci marked, respectively.

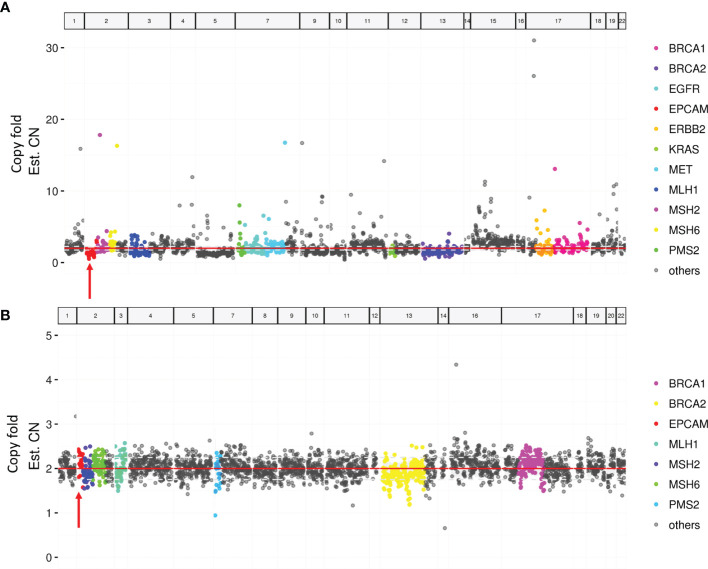

Paired tumor and blood samples were collected for MMR gene testing by NGS in the case with MSH2 expression loss. Neither germline nor somatic mutations in MMR genes were detected. However, a possible somatic EPCAM copy-number deletion was detected ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Targeted next-generation sequencing of paired tumor and blood samples. (A) A possible EPCAM deletion in tumor sample (arrow). (B) No EPCAM germline deletion in the blood sample (arrow).

Relationship Between Mismatch Repair/Microsatellite Instability Status and Clinicopathological Parameters and Survival in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

The only dMMR case, which exhibited MSH2 loss, was a 68-year-old woman without any family history of colorectal or endometrial cancer. The patient had high-grade invasive cancer of no special histological type with no lymph node metastasis, positive immunostaining for P53 and basal-like markers (EGFR and CK5/6), and a Ki-67 proliferative index of 35%. This patient, who was the only patient with dMMR, showed no recurrence during this study.

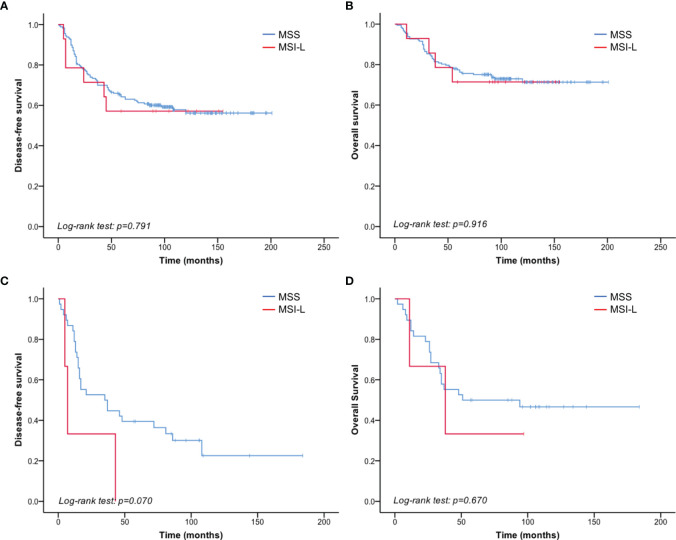

Given that no MSI-H patients were identified by PCR testing, we compared the clinicopathological parameters between MSS and MSI-L in 195 patients of known MSI status. There was no significant correlation between MSI status and clinicopathological parameters ( Table 4 ). And no significant difference was found in DFS or OS between MSI-L and MSS patients (p = 0.791 and 0.916 of all stages, p=0.073 and 0.671 of stage III, respectively) ( Figure 3 , Tables 5 , 6 ).

Table 4.

MSI phenotype and pathological parameters.

| Pathological Parameters | No. of Patients | MSI phenotype | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSS | MSI-L | |||

| Age at diagnosis | 0.406 | |||

| ≤49 | 97 | 92 | 6 | |

| >49 | 98 | 89 | 9 | |

| Histological grade | 0.546 | |||

| I | 9 | 8 | 1 | |

| II | 51 | 49 | 2 | |

| III | 135 | 124 | 11 | |

| Tumor size | 0.156 | |||

| pT1 | 81 | 78 | 3 | |

| pT2 | 106 | 95 | 11 | |

| pT3 | 8 | 8 | 0 | |

| Nodal status | 0.295 | |||

| negative | 110 | 101 | 9 | |

| 1–3 nodes | 45 | 43 | 2 | |

| 4–9 nodes | 19 | 19 | 0 | |

| ≥10 nodes | 21 | 18 | 3 | |

| TNM Stage | 0.516 | |||

| I | 52 | 50 | 2 | |

| II | 101 | 92 | 9 | |

| III | 42 | 39 | 3 | |

| Basal-like | 1.000 | |||

| Negative | 43 | 40 | 3 | |

| Positive | 152 | 141 | 11 | |

| Ki67 index* | 0.473 | |||

| ≤14 | 32 | 31 | 1 | |

| >14 | 163 | 150 | 13 | |

| TILs | 0.753 | |||

| High | 49 | 45 | 4 | |

| Low | 146 | 136 | 10 | |

| Surgery | 1.000 | |||

| Breast-conserving | 20 | 19 | 1 | |

| Radical mastectomy | 175 | 162 | 13 | |

| Chemotherapy | 1.000 | |||

| Negative | 30 | 28 | 2 | |

| Positive | 157 | 146 | 11 | |

| Radiotherapy | 1.000 | |||

| Negative | 149 | 137 | 12 | |

| Positive | 34 | 32 | 2 | |

| P53 | 1.000 | |||

| Negative | 101 | 94 | 7 | |

| Positive | 93 | 86 | 7 | |

| PD-1 | 0.129 | |||

| Negative | 59 | 52 | 7 | |

| Positive | 136 | 129 | 7 | |

| PD-L1 | 0.604 | |||

| Negative | 182 | 168 | 14 | |

| Positive | 13 | 13 | 0 | |

MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; MSI-L, low-frequency microsatellite instability; TNM, Primary Tumor/Regional Lymph Nodes/Distant Metastasis; TILs, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; *Ki-67 index threshold of 14% was chosen according to the St. Gallen Consensus 2013.

Figure 3.

MSI status did not correlate with TNBC prognosis. (A) No significant difference in DFS was detected between the MSI-L and MSS patients of all stages. (B) No significant difference was detected in OS between the MSI-L and MSS groups of all stages. (C) Shorter DFS was observed in MSI-L patients than in MSS patients with stage III breast cancer. (D) No significant difference in OS was observed between MSI-L and MSS patients with stage III breast cancer.

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of prognostic value of clinicopathological factors and MSI phenotype of DFS and OS in patients of all stages.

| Variable (DFS) | DFS | p | OS | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Age at diagnosis | 0.374 | 0.032 | ||

| ≤49 | 1 | |||

| >49 | 0.539 (0.306–0.949) | |||

| Menopause | 0.496 | 0.913 | ||

| Pre-menopausal | ||||

| Post-menopausal | ||||

| Histological grade | 0.457 | 0.945 | ||

| I | ||||

| II | ||||

| III | ||||

| Tumor size | 0.009 | 0.039 | ||

| pT1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| pT2 | 1.304 (0.813–2.09) | 1.742 (0.946–3.207) | ||

| pT3 | 3.988 (1.646–9.661) | 3.784 (1.255–11.409) | ||

| Nodal status | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| negative | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1–3 nodes | 1.851 (1.051–3.261) | 1.277 (0.598–2.73) | ||

| 4–9 nodes | 2.183 (1.035–4.606) | 2.625 (1.108–6.217) | ||

| ≥10 nodes | 8.355 (4.694–14.872) | 6.488 (3.303–12.743) | ||

| TNM Stage | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| I | 1 | 1 | ||

| II | 1.541 (0.817–2.907) | 1.428 (0.636–3.209) | ||

| III | 4.632 (2.408–8.909) | 4.755 (2.113–10.702) | ||

| Basal-like phenotype | 0.807 | 0.169 | ||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| Ki67 index* | 0.589 | 0.535 | ||

| ≤14 | ||||

| >14 | ||||

| TILs | 0.156 | 0.198 | ||

| Low | ||||

| High | ||||

| Surgery | 0.265 | 0.459 | ||

| Breast-conserving | ||||

| Radical mastectomy | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.949 | 0.234 | ||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | 0.266 | |||

| Radiotherapy | 0.580 | |||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| P53 | 0.799 | 0.880 | ||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| MSI | 0.791 | 0.916 | ||

| MSS | ||||

| MSI-L |

MSI, microsatellite instability; DFS, Disease-free survival; OS, Overall survival; TNM, Primary Tumor/Regional Lymph Nodes/Distant Metastasis; TILs, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; MSS, microsatellite stable; MSI-L, low-frequency microsatellite instability.

*Ki-67 index threshold of 14% was chosen according to the St. Gallen Consensus 2013.

Table 6.

Univariate analysis of prognostic value of clinicopathological factors and MSI phenotype of DFS and OS of patients with stage III.

| Variable (DFS) | DFS | p | OS | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Age at diagnosis | 0.991 | 0.511 | ||

| ≤49 | ||||

| >49 | ||||

| Menopause | 0.028 | 0.427 | ||

| Pre-menopausal | 1 | |||

| Post-menopausal | 2.284 (1.095–4.764) | |||

| Histological grade | 0.996 | 0.600 | ||

| I | ||||

| II | ||||

| III | ||||

| Tumor size | 0.295 | 0.693 | ||

| pT1 | ||||

| pT2 | ||||

| pT3 | ||||

| pT4 | ||||

| Nodal status | 0.003 | 0.155 | ||

| 1–3 nodes | 1 | |||

| 4–9 nodes | 1.3 (0.163–10.339) | |||

| ≥10 nodes | 4.808 (0.636–36.334) | |||

| Basal-like phenotype | 0.986 | 0.616 | ||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| Ki67 index* | 0.222 | 0.062 | ||

| ≤14 | 1 | |||

| >14 | 6.778 (0.909–50.526) | |||

| TIL | 0.277 | 0.330 | ||

| Low | ||||

| High | ||||

| Surgery | 0.100 | 0.059 | ||

| Breast-conserving | 1 | |||

| Radical mastectomy | 0.293 (0.082–1.045) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 0.432 | 0.143 | ||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 0.037 | 0.009 | ||

| Negative | 1 | 1 | ||

| Positive | 0.435 (0.199–0.951) | 0.272 (0.102–0.721) | ||

| P53 | 0.726 | 0.525 | ||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| MSI | 0.073 | 0.671 | ||

| MSS | 1 | 1 | ||

| MSI-L | 2.894 (0.857–9.774) | 1.368 (0.319–5.865) |

MSI, microsatellite instability; DFS, Disease-free survival; OS, Overall survival; TNM, Primary Tumor/Regional Lymph Nodes/Distant Metastasis; TILs, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; MSS, microsatellite stable; MSI-L, low-frequency microsatellite instability.

*Ki-67 index threshold of 14% was chosen according to the St. Gallen Consensus 2013.

Discussion

Both dMMR and MSI-H have been identified as effective predictors of immunotherapy response (10, 11). The exploration of MSI status as a predictive biomarker has been carried out in a broad range of tumor types. Large-scale analysis showed that MSI-H occurred infrequently (1%–5%) in cancer types not conventionally associated with an MSI-H phenotype (28). Furthermore, MSI testing revealed a larger spectrum of tumors relating to Lynch syndrome compared to previous reports (29). Universal screening for MMR/MSI status is now being recommended in routine oncological care of patients with solid tumors regardless of the cancer’s origin. Consequently, MMR/MSI status in breast cancer has also garnered attention. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical relevance of MMR/MSI status in Chinese women with TNBC in order to determine the frequency of dMMR/MSI-H and its potential for predicting the outcome of immunotherapy.

We demonstrated that the frequency of dMMR and MSI-H was 0.2% (1/440) and 0%, respectively, in a relatively large cohort. To our knowledge, this is the largest TNBC cohort evaluated for dMMR/MSI-H to date. These results were similar to those of a previous report that included a smaller cohort of TNBC patients (30). Our results suggest that dMMR/MSI-H is very rare in sporadic cases of TNBC, although patients with MSI-H may benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors. The frequency of MMR defects in sporadic breast cancer is reported to be 0% to 20%, while in breast cancer with MMR gene mutations, the frequency of dMMR/MSI-H is reported to be higher, with 65% of patients displaying dMMR and 35% displaying MSI-H (21). Therefore, it may not be feasible to screen for MMR/MSI status in routine clinical tests unless there is proof of Lynch syndrome-related cancer, such as family history or the presence of multiple tumors (31). Evaluation of TILs in the TNBC microenvironment might be more useful for predicting the efficiency of immunotherapy (32). Using a relatively large cohort, our study conclusively showed the extremely rareness of dMMR/MSI-H in TNBC, which indicated that it might be necessary to identify other biomarkers for predicting immunotherapy outcomes in TNBC, such as TILs and immune gene evaluation. However, in view of the extremely low frequency of dMMR/MSI-H, whether MSI/MMR status is an effective indicator of immunotherapy response or prognosis in patients with TNBC needs further clarification.

In dMMR tumors, MSH2 protein loss, traditionally evaluated by immunochemical staining, generally occurs concurrently with loss of MSH6 protein expression. However, one patient in our cohort exhibited an abnormal staining pattern, showing an isolated loss of MSH2 with intact MSH6 expression. This discordance in IHC results could not be ascribed to the variable reactivity or subjective interpretations, given the robust internal control (intervening stroma) used in the staining procedure. Similar staining patterns (retained MSH6 expression with the absence of MSH2), which were attributed to germline or somatic MSH2 mutations, have been previously reported in colorectal cancer (33). To confirm the MSI status, PCR was performed. Intriguingly, PCR showed that the dMMR tumor was MSI-L, indicating an inconsistency between the results of the MMR IHC staining and the MSI test. This unusual inconsistency has been rarely reported in cancers that are not typical Lynch syndrome-related tumors, including adrenocortical carcinoma, peritoneal mesothelioma, pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (34). One potential explanation is that the accumulation of detectable MSI was a secondary event that only occurred at a later stage, after the dysfunction of MMR proteins. To further clarify the genetic mechanisms underlying the MSH2 protein loss in this case, we conducted NGS-based testing. Results from NGS testing revealed a possible EPCAM copy-number deletion in the tumor tissue. It has been documented that 3’ EPCAM deletion causes transcriptional read-through of the mutated EPCAM allele, resulting in epigenetic inactivation and silencing of its neighboring gene MSH2 (35).

dMMR/MSI is useful for predicting treatment outcomes for some malignancies, including colon cancer (15). Previous studies have evaluated dMMR/MSI status in breast cancer, but the prognostic significance was inconsistent. One study on 248 patients with breast cancer demonstrated that MSI-H has no significant impact on patient survival or PD-L1 expression (30). In contrast, some studies have reported the prognostic value of dMMR/MSI-H status in breast cancer (20, 22–24). In our cohort of TNBC patients, only one patient could be characterized as dMMR based on the lack of MSH2 expression. This patient did not exhibit recurrence and/or metastasis until the final follow-up. PCR and NGS only identified a small number of MSI-L cases. Unlike MSI-H tumors, MSI-L tumors appear to arise via the chromosomal instability pathway (36). Few studies have described the prognostic value of MSI-L. Therefore, we further analyzed the prognostic significance of MSI-L and its relationship with clinicopathological characteristics in TNBC. Our retrospective study revealed that patients with an MSI-L phenotype had relatively poorer survival than those with an MSS phenotype. Of the patients with stage III cancer, MSI-L patients had a median DFS of 7 months, while MSS patients had a median DFS of 35 months. However, the difference in DFS was not significant (p = 0.073). Similar results have been observed in patients with colon cancer (37). No significant relationship was found for MSI-L and age, tumor size, grade, Ki-67 index, P53, PD-1/PD-L1 expression, and the number of TILs. There have been new advances in increasing the efficacy of immunotherapy in colorectal cancers that are MMR-proficient and characterized as MSI-L (38). However, albeit the lack of significant correlation between MSI-L phenotype and clinicopathological characteristics in our study, we should be aware of the limitations imposed by the small numbers of cases with MSI-L, and further studies are needed to validate the findings in a larger cohort.

In conclusion, the incidence of dMMR/MSI-H is extremely low in patients with TNBC. Moreover, MMR/MSI status was not associated with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and showed little prognostic significance in TNBC. Further studies are required to explore biomarkers with a predictive capacity for immunotherapy outcomes in patients with TNBC.

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data has been deposited into BioProject (accession: PRJNA639238).

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Peking Union Medical College Hospital Institutional Review Board (PUMCH IRB). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

X-yR conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, performed the formal analysis, and wrote, edited, and reviewed the manuscript. YS conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, conducted the investigation, was in charge of the data curation, and wrote the manuscript. L-yC developed the methodology, conducted the investigation, and provided the resources. J-yP developed the methodology, conducted the investigation, and provided the resources. S-jS developed the methodology and reviewed the manuscript. M-mS developed the methodology and reviewed the manuscript. Z-yL conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, reviewed the manuscript, acquired the funding, and supervised the study. QS conceptualized the study, reviewed the manuscript, was in charge of the project administration, and supervised the study. H-wW conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, reviewed the manuscript, and was in charge of the project administration. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by CAMS Central Public Welfare Scientific Research Institute Basal Research Funds Clinical and Translational Medicine Research Program (2019XK320045) and CAMS Initiative for Innovative Medicine (2016-I2M-1-002). The funding source took no part in the design or conduct of the study.

Conflict of Interest

M-mS was employed by the company Beijing Microread Genetics Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for the English language editing.

References

- 1. Althobiti M, Aleskandarany MA, Joseph C, Toss M, Mongan N, Diez-Rodriguez M, et al. Heterogeneity of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer and its prognostic significance. Histopathology (2018) 73(6):887–96. 10.1111/his.13695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu W-J, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti–PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. New Engl J Med (2012) 366(26):2455–65. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wimberly H, Brown JR, Schalper K, Haack H, Silver MR, Nixon C, et al. PD-L1 expression correlates with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Res (2015) 3(4):326–32. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ren X, Wu H, Lu J, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Xu Q, et al. PD1 protein expression in tumor infiltrated lymphocytes rather than PDL1 in tumor cells predicts survival in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther (2018) 19(5):373–80. 10.1080/15384047.2018.1423919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Overman MJ, Mcdermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi S, André T. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): An open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18 (9):1182–91. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30422-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luchini C, Bibeau F, Ligtenberg MJL, Singh N, Nottegar A, Bosse T, et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: a systematic review-based approach. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol (2019) 30(8):1232–43. 10.1093/annonc/mdz116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Imai K, Yamamoto H. Carcinogenesis and microsatellite instability: The interrelationship between genetics and epigenetics. Carcinogenesis (2008) 29(4):673–80. 10.1093/carcin/bgm228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ligtenberg MJ, Kuiper RP, Chan TL, Goossens M, Hebeda KM, Voorendt M, et al. Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3’ exons of TACSTD1. Nat Genet (2009) 41(1):112–7. 10.1038/ng.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glaire MA, Brown M, Church DN, Tomlinson I. Cancer predisposition syndromes: lessons for truly precision medicine. J Pathol (2017) 241(2):226–35. 10.1002/path.4842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science (2017) 357(6349):409–13. 10.1126/science.aan6733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao P, Li L, Jiang X, Li Q. Mismatch repair deficiency/microsatellite instability-high as a predictor for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy efficacy. J Hematol Oncol (2019) 12(1):54. 10.1186/s13045-019-0738-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prasad V, Kaestner V, Mailankody S. Cancer Drugs Approved Based on Biomarkers and Not Tumor Type-FDA Approval of Pembrolizumab for Mismatch Repair-Deficient Solid Cancers. JAMA Oncol (2018) 4(2):157–8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawakami H, Zaanan A, Sinicrope FA. Microsatellite instability testing and its role in the management of colorectal cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol (2015) 16(7):30. 10.1007/s11864-015-0348-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Polom K, Marano L, Marrelli D, De Luca R, Roviello G, Savelli V, et al. Meta-analysis of microsatellite instability in relation to clinicopathological characteristics and overall survival in gastric cancer. Br J Surg (2018) 105(3):159–67. 10.1002/bjs.10663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, Thibodeau SN, French AJ, Goldberg RM, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. New Engl J Med (2003) 349(3):247–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa022289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Timmerman S, Van Rompuy AS, Van Gorp T, Vanden Bempt I, Brems H, Van Nieuwenhuysen E, et al. Analysis of 108 patients with endometrial carcinoma using the PROMISE classification and additional genetic analyses for MMR-D. Gynecologic Oncol (2020) 157(1):245–51. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiappini F, Grossgoupil M, Saffroy R, Azoulay D, Emile JF, Veillhan LA, et al. Microsatellite instability mutator phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic and non-virally infected normal livers. 25 (2004) 4):541–7. 10.1093/carcin/bgh035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim ST, Klempner SJ, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, et al. Correlating programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, mismatch repair deficiency, and outcomes across tumor types: implications for immunotherapy. Oncotarget (2017) 8(44):77415–23. 10.18632/oncotarget.20492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eatrides JM, Coppola D, Al Diffalha S, Kim RD, Springett GM, Mahipal A. Microsatellite instability in pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol (2016) 34 (15_suppl):e15753. 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.e15753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fusco N, Lopez G, Corti C, Pesenti C, Colapietro P, Ercoli G, et al. Mismatch Repair Protein Loss as a Prognostic and Predictive Biomarker in Breast Cancers Regardless of Microsatellite Instability. JNCI Cancer Spectr (2018) 2(4):pky056. 10.1093/jncics/pky056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lotsari JE, Gylling A, Abdel-Rahman WM, Nieminen TT, Aittomäki K, Friman M, et al. Breast carcinoma and Lynch syndrome: molecular analysis of tumors arising in mutation carriers, non-carriers, and sporadic cases. Breast Cancer Res BCR (2012) 14(3):R90. 10.1186/bcr3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wild PJ, Reichle A, Andreesen R, Röckelein G, Dietmaier W, Rüschoff J, et al. Microsatellite instability predicts poor short-term survival in patients with advanced breast cancer after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation. Clin Cancer Res (2004) 10(2):556–64. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0601-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paulson TG, Wright FA, Parker BA, Russack V, Wahl GM. Microsatellite instability correlates with reduced survival and poor disease prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Res (1996) 56(17):4021–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kamat N, Khidhir MA, Jaloudi M, Hussain S, Alashari MM, Qawasmeh KHA, et al. High incidence of microsatellite instability and loss of heterozygosity in three loci in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a prospective study. BMC Cancer (2012) 12:373. 10.1186/1471-2407-12-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schalper KA, Velcheti V, Carvajal D, Wimberly H, Brown J, Pusztai L, et al. In situ tumor PD-L1 mRNA expression is associated with increased TILs and better outcome in breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2014) 20(10):2773–82. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-13-2702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giuliano AE, Edge SB, Hortobagyi GN. Eighth Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol (2018) 25(7):1783–5. 10.1245/s10434-018-6486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Wolff AC, Mangu PB, Temin S. American society of clinical oncology/college of american pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Oncol Pract (2010) 6(4):195–7. 10.1200/jop.777003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hause RJ, Pritchard CC, Shendure J, Salipante SJ. Classification and characterization of microsatellite instability across 18 cancer types. Nat Med (2016) 22(11):1342–50. 10.1038/nm.4191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Latham A, Srinivasan P, Kemel Y, Shia J, Bandlamudi C, Mandelker D, et al. Microsatellite Instability Is Associated With the Presence of Lynch Syndrome Pan-Cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2019) 37(4):286–95. 10.1200/jco.18.00283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mills AM, Dill EA, Moskaluk CA, Dziegielewski J, Bullock TN, Dillon PM. The relationship between mismatch repair deficiency and PD-L1 expression in breast carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol (2018) 42(2):183–91. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sorscher S. Rationale for evaluating breast cancers of Lynch syndrome patients for mismatch repair gene expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2019) 178(2):469–71. 10.1007/s10549-019-05394-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wein L, Savas P, Luen SJ, Virassamy B, Salgado R, Loi S. Clinical Validity and Utility of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Routine Clinical Practice for Breast Cancer Patients: Current and Future Directions. Front Oncol (2017) 7:156. 10.3389/fonc.2017.00156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pearlman R, Markow M, Knight D, Chen W, Arnold CA, Pritchard CC, et al. Two-stain immunohistochemical screening for Lynch syndrome in colorectal cancer may fail to detect mismatch repair deficiency. Modern Pathol an Off J U States Can Acad Pathol Inc (2018) 31(12):1891–900. 10.1038/s41379-018-0058-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karamurzin Y, Zeng Z, Stadler ZK, Zhang L, Ouansafi I, Al-Ahmadie HA, et al. Unusual DNA mismatch repair-deficient tumors in Lynch syndrome: a report of new cases and review of the literature. Hum Pathol (2012) 43(10):1677–87. 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tutlewska K, Lubinski J, Kurzawski G. Germline deletions in the EPCAM gene as a cause of Lynch syndrome - literature review. Hered Cancer Clin Pract (2013) 11(1):9. 10.1186/1897-4287-11-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pawlik TM, Raut CP, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. Colorectal carcinogenesis: MSI-H versus MSI-L. Dis Markers (2004) 20(4-5):199–206. 10.1155/2004/368680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Kashfi SM, Mirtalebi H, Taleghani MY, Azimzadeh P, Savabkar S, et al. Low Level of Microsatellite Instability Correlates with Poor Clinical Prognosis in Stage II Colorectal Cancer Patients. J Oncol (2016) 2016:2196703. 10.1155/2016/2196703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek A, Mendelsohn RB, Shia J, Segal NH, et al. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 16(6):361–75. 10.1038/s41575-019-0126-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data has been deposited into BioProject (accession: PRJNA639238).