Abstract

Purpose

To identify approaches, enablers, barriers and outcomes of facility stillbirth and neonatal death audit in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL Complete, Academic Search Index, Science Citation Index, Complementary index and Global health electronic databases.

Study selection

Studies were considered eligible when reporting the approaches, enablers, barriers and outcomes of facility-based stillbirth and neonatal death audit in LMICs.

Data extraction

Two authors independently performed the data extraction using predefined templates made before data extraction.

Results of data synthesis

A total of 10 articles from 7 countries were included in the final analysis. Facility or external multidisciplinary teams performed death audits on a weekly or monthly basis. A total of 1018 stillbirths and neonatal deaths were audited. Of 18 audit enablers identified, nine were at the health provider level while 18 of 23 barriers to audit that were identified occurred at the facility level. The facility-level barriers cited by more than one study included: failure to implement change; inadequate training; limited time; increased workload; too many cases and poor documentation. Six studies reported that death audits resulted in structural improvements in physical structure, training, service organisation, supplies and equipment in the wards. Five studies reported that death audits improved the standard of care, with one study showing a significant improvement in measured standards. One study reported a significant reduction in newborn mortality rate of 29.4% (95% CI 0.6% to 2.4%; p=0.0015) and one study a reduction in perinatal mortality of 4.9% (52.8% in 2007 to 47.9% in 2008) before and after perinatal audit implementation.

Conclusion

Stillbirth and neonatal death audit improves facility structures, processes of care and health outcomes in neonatal care. There is a need to enhance enablers and address barriers identified at both health provider and facility levels to improve the audit process.

Keywords: audit and feedback, clinical audit, infant mortality, hospital medicine, hospital mortality

Introduction

Improving access to healthcare alone is not enough to improve patient outcomes.1 Recently, a focus on the quality of care (QoC) was advocated to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2030 of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages. Poor QoC is not only harmful but also wastes resources that could have been used in other sectors to improve the lives of citizens.1

Despite increased facility-based births, women and babies are still dying or developing lifelong disabilities due to poor QoC.2 WHO estimates 295 000 women and 2.5 million newborns die every year during childbirth from preventable causes. Furthermore, 2.6 million stillbirths occur each year. About 98% of these deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).3–5

Providing high QoC in LMICs remains a challenge and performance varies across providers.1 Implementing quality improvement is possible in these countries through identifying problems in care and adopting best practice. Table 1 summarises definitions for stillbirth and neonatal deaths. WHO has recommended auditing stillbirths and neonatal deaths to identify and implement ways to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care.6 However, progress in LMICs has been limited compared with high-income countries.7

Table 1.

Definitions of stillbirth and neonatal deaths

| Stillbirth | A baby born dead at ≥28 weeks of gestation, or birth weight of ≥1000 g, or a body length of ≥35 cm |

| Antepartum stillbirth (macerated stillborn) | Death of a fetus before the onset of labour characterised by skin changes and peelings |

| Intrapartum stillbirth (fresh stillborn) | Death of a fetus during labour |

| Neonatal death | Death of a baby within the first 28 days of life |

| Early neonatal death | Death of a baby within the first 7 days of life |

| Late neonatal death | Death of a baby between 8 and 28 days of life |

| Perinatal deaths | Stillbirths and early neonatal deaths |

Stillbirth and neonatal death audit is the process of capturing information on the causes of deaths and analysing the QoC received, in a no-blame, interdisciplinary setting to improve the care provided to all mothers and babies.6 Through the process, the hospital staff have an opportunity to learn from the cases audited and improve care.

Many factors hinder or facilitate the successful implementation of auditing stillbirths and neonatal deaths.7 Critically, the effectiveness of audit depends on the ability to complete the audit process. Without effectively implementing the planned actions to respond to the problems identified, the audit alone cannot improve QoC.8 Also, effective audit requires a system-wide effort to support the recommended initiatives. However, challenges related to system support, formulating appropriate recommendations based on preventable factors and implementing changes have been reported.7 9

This systematic review will contribute to the existing evidence base by synthesising data on facility stillbirth and neonatal death audits and provide guidance on how to undertake a successful stillbirth and neonatal death audit initiative in LMICs. We address the following objectives:

To evaluate and synthesise the evidence on the approaches and outcomes of facility based stillbirth and neonatal death audit on QoC and perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in LMICs.

To identify enablers and barriers at health provider, facility and regional or national levels of care, to the implementation of successful stillbirth and neonatal death audits in LMICs.

Our work will serve as a guide to facility stillbirth and neonatal death audit implementation by evaluating the evidence on approaches used, outcome measures, opportunities and challenges to guide future healthcare workers undertaking similar initiatives to ensure that it is evidence based.

Methods

We registered the review on the International Register of Systematic Prospective Reviews (registration number: CRD42019148515) and used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.10

Search strategy

In September 2019, we searched MEDLINE, CINAHL Complete, Academic Search Index, Science Citation Index, Complementary index and Global health for eligible studies from January 2009 to August 2019. Included search terms were “stillb*” OR “neonat*” OR “perinatal death” OR “neonatal death” AND audit OR review (online supplemental material box 1S).

bmjoq-2020-001266supp001.pdf (211.2KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies if they met all of the following criteria: (1) studies describing approaches, enablers, barriers or reporting outcomes of stillbirth and neonatal death audits at the facility level; (2) original research article reporting either quantitative, qualitative data or both (3) study done in LMIC(s) defined and identified according to World Bank list;11 (4) studies which implemented a full audit process; (5) published in English and (6) published between 1 January 2009 and 1 September 2019 (search date). We selected studies published since January 2009 as many LMICs become proactive in addressing quality problems from this date12 and we aimed to focus the review on current practice. We excluded studies that only reported descriptive findings of audits as such reviews have been well covered elsewhere.13–15 We excluded systematic reviews as we were only interested in original research articles.

Quality appraisal

We used the checklist for reviewing disparate data developed by Hawker et al16 to appraise the studies (online supplemental material box 2S). The checklist comprises nine questions, each of which has four sub-categories, permitting summation of a methodological quality score. Each paper was rated on a scale from 9 (very poor) to 36 (good).

Data extraction and analysis

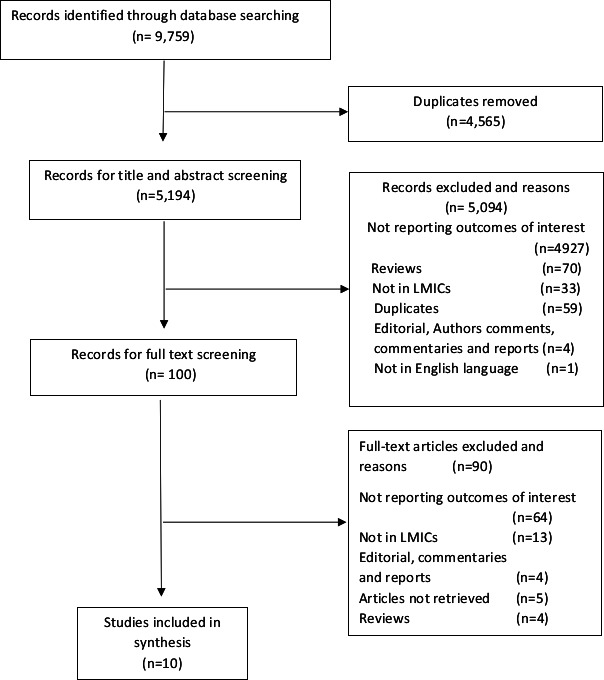

Two authors (MJG and JMM) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility (figure 1). A third author (MA) resolved any discrepancies. Articles approved for full-text screening were reviewed by the two authors (MJG and JMM) independently by applying the pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above; if there was disagreement, we reached consensus through discussion.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. LMICs, low-income and middle-income countries.

One author (MJG) performed data extraction and quality appraisal using pre-defined templates, made by the authors before the literature search. Another author (JMM) was consulted in case of uncertainty.

Since the included studies were heterogeneous regarding design and outcomes, we used the narrative approach to synthesise the evidence. We reported characteristics related to (1) publication, (2) study, (3) audit type, (4) approaches, (5) structure outcomes, (6) process outcomes, (7) health outcomes and (8) enablers and barriers. We classified the approaches, enablers and barriers according to the Kruk and Gage schema ‘synthesising improvement approaches’.17 This guide classifies approaches at micro, meso and macrosystem levels, meaning health provider level; health facility, district or clinic level; and across health system or national level, respectively.

Results

Study selection

The searches resulted in 9759 articles across all of the databases. After excluding 4565 duplicates, we screened 5194 titles and abstracts. Of these, we excluded 5094 articles for not meeting the inclusion criteria (figure 1). The remaining 100 articles underwent full-text review. Common reasons for exclusion at this stage were not reporting outcomes of interest (n=64) and not done in LMICs (n=13) according to World Bank Classification.11 All studies were rated for quality as fair with a score ranging from 23 to 32 (online supplemental material table 1S). We finally identified ten studies as appropriate for inclusion in the synthesis.

Characteristics of studies

Ten studies from seven countries met the inclusion criteria: Tanzania (three studies), Uganda (two) and one study each from Bangladesh, Moldova, Solomon Islands, Ethiopia and Zambia. Online supplemental table 2S summarises the study designs. Six quantitative,9 18–22 two qualitative23 24 and two mixed-method studies25 26 were identified. All studies were uncontrolled and described the outcome of stillbirth and neonatal death audit, with a before or after analysis, except two studies with a qualitative design.23 24 Audits were conducted either weekly9 21 22 or monthly.18 19 Study duration ranged from 1 month24 to 48 months (online supplemental table 1S).19 The deaths audited in all studies were perinatal deaths (stillbirths and early neonatal deaths) except one study which audited deaths in neonates (0–28 days) and older children.9 The total number of cases audited ranged from a minimum of 5 to a maximum of 146 deaths per month (online supplemental table 1S). A total of 1018 stillbirths and neonatal deaths were audited.

Four studies with a qualitative or mixed-methods design23–26 interviewed facility staff and key informants to understand the process of stillbirth and neonatal death audits in hospitals. The following data collection methods were used: document review,23 24 focus group discussion (FGD)23 and in-depth interviews (IDIs).23–26 The staff and key informants interviewed for IDIs and FGD varied between studies. However, IDIs and FGD included facility staff involved in the process of auditing at the private hospital, health centre, district hospital and central hospital level. Staff included were doctors, nurses, administration staff, surgeons, family planning officers, health managers and other members of the audit committee. The number of participants in each study for IDIs ranged from 29 to 66 participants.25 26 Five doctors and six nurses participated in FGD conducted by one study.23

Stillbirth and neonatal death audit approaches

Two approaches were reported by six studies in this analysis.9 10 20–23 The first three studies used multidisciplinary facility teams to audit deaths and develop and implement recommendations.9 18 22 In these studies, the lead member of the audit team was either a senior obstetrician or paediatrician or nurse. Although the composition of multidisciplinary teams differed between studies, in all three studies it consisted of obstetricians, paediatricians, medical officers, midwives, administrators, nurses, neonatologists, neonatal fellows and neonatal and delivery unit in charges. One study had only senior staff in the audit team.18 All studies used standard mortality audit forms adapted from WHO for gathering clinical information. One study also included verbal autopsy questions for guardians and staff.18

The second three studies used a confidential inquiry approach19 or external researchers20 or external and internal auditors.21 These external multidisciplinary teams were not involved in the care of patients; they audited the cases and gave feedback to facility staff to implement recommendations.

Of six studies that reported audit approaches,9 10 20–23 five studies were prospective death audits, while one was retrospective and then prospective during reaudit.23 One study used a criteria-based audit approach, where initial death audit of fresh stillbirths was undertaken and developed standards as a benchmark to improve care.21 This was followed up by reaudit of stillbirths to assess adherence to standards. Most death audit approach activities were implemented at the facility level (eg, conducting audits, recommending solutions, implementing recommendations and training). Four studies reported engagement at the national level and two studies19 22 reported national stakeholder engagement through developing guidelines, coordinating audit and disseminating the findings. In contrast, two studies20 21 reported the use of external panel members or researchers at the national level. Online supplemental table 3S summarises the approaches.

Outcomes of stillbirth and neonatal death audit

Structure

Six studies9 10 20–23 reported structural improvements in one or more areas that improved the care of women in labour and neonates in the wards (table 2). Most changes were related to the physical structure of the ward; purchasing of essential supplies and equipment; training, staffing and organisation of services in the ward. Table templates for tables 2 and 3 were adapted from Lazzerini et al.27

Table 2.

Structural outcomes*

| Author/year | Ward physical structure | Staffing | Equipment and supplies | Training | Service organisation |

| Demise, 201518 | Increased use of radiant warmers in NICU | _ | _ | Refresher training on neonatal resuscitation for midwives and physicians | Improved administration of antepartum steroids Implementation of KMC Using transport incubators and cellophane wraps |

| Stratulat, 201419 | _ | _ | _ | _ | Routine audit sessions established Adaptation of audit guidelines and tool used at national level National level involvement in coordinating audit meetings developed 15 clinical practice protocols for neonatal care |

| Nakibuuka, 201222 | Created Space for resuscitation in labour wards and NICU | Recruited more anaesthetists. Doctors involved in preoperative care |

Ambu-bags and masks provided in the labour ward and newborn unit | Trained midwives and doctors on labour and partograph use Trained Intern doctors and midwives on neonatal resuscitation, respiratory distress and CPAP |

New standards developed for the caesarean section decisions and disseminated Neonatal resuscitation protocols displayed in wards |

| Sandakabatu, 20189 | _ | _ | _ | Teaching opportunities during child death review meetings | Quality improvement team established |

| Kidanto, 200920 | _ | _ | Purchased New sets) of vacuum and Doppler machines | 120 midwives and doctors trained in the use of partograph, abnormal labour and newborn resuscitation Nurses/midwives routine CPD sessions weekly | Established an audit committee Introduced daily and monthly assessments of all perinatal deaths management protocols for eclampsia and other obstetrics emergencies developed and pasted in the wards established a record tracing the patient from the labour ward to the theatre to reduce delays obstetrician on call stationed in the labour ward |

| Kasengele, 201721 | _ | _ | _ | _ | Doctors on call slept in the hospital weekly perinatal reviews and feedback |

*Table template was adapted from reference.27

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CPD, Continuous Professional Development; KMC, Kangaroo mother care; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 3.

Mortality, morbidity and process of care outcomes*

| Author/year | Mortality perinatal, neonatal and stillbirths |

Morbidity (neonatal, perinatal and maternal | Standard of care | Other process outcomes |

| Stratulat, 201419 | Proportional mortality rates among fetuses/ newborns with a gestational age of ≥37 weeks and with a birth weight of ≥2500 g for the years 2005–2013. The proportional mortality rate decreased from 5.1 per 1000 in 2006 to 3.6 per 1000 in 2013 (with 1.5 per 1000 or 29.4% reduction, 95% CI 0.6 to 2.4; z-value 3.2; p=0.0015). | Improvements in the standards of care through multidisciplinary audit sessions and a no-blame approach Improved management of cases (breech presentation, cord pathology and Intrauterine growth retardation monitoring) | Improved birth records partograph updated and modernised Improved documentation tools for perinatal deaths partograph used correctly and appropriate Improved clinical decision making for complicated cases from 44% in 2007 to 82% in 2010 Recognised the role of other professionals (social workers and psychologist) in preventing perinatal deaths strengthened collaboration across borders |

|

| Nakibuuka, 201222 | The overall perinatal mortality rate in 2008 was 47.9 compared with 52.8 per 1000 total births in 2007 | _ | _ | _ |

| Kidanto, 200920 | _ | _ | _ | Improved referral system to reduce delays Improved documentation |

| Kasengele, 201721 | _ | Obstructed labour accounted for 55.7% (n=64) in the initial audit and 38.7% (n=12) in the reaudit Antepartum haemorrhage accounted for 23.5% (n=27) at baseline and 16.1% (n=5) at re-audit. Unknown causes increased from 14.8% (n=17) in the initial audit to 38% (n=12) in the reaudit. |

Increases occurred in: Partograph usage (from 36 (31.3%) to 20 (65%)) All Severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia cases received correct treatment of magnesium sulphate at both initial and reaudit referral of women with obstructed labour (31 (48%) to 11 (92%)); women catheterised (22 (38%) to 7 (58%)); women reviewed within 15 min (2 (3%) to 4 (33%)); C/S operating staff notified (31 (37%) to 16 (100%)); C/S done within 10 min (31 (37%) to 12 (78%)) |

*Table tampelate was adapted from reference.27

C/S, Caesarean Section; Dash (-), not reported.

Process

Five studies reported changes in the process of care. One study21 cited quantitative process outcomes against eight predefined standards, and all eight standards showed some significant improvement (table 3). Another study,19 reported improvements in standard care and case management of complications during labour and delivery. Other process outcomes reported by three studies19 20 25 were improved fetal heart rate monitoring, doppler device use, data documentation, partograph use, clinical decision making for complicated cases, referral system, the involvement of other professionals (social workers and psychologist) in the audit.

Outcomes (health)

Newborn outcomes were reported in only a few studies (table 3). Only two studies reported newborn/perinatal mortality.19 22 One study (21) reported a statistically significant reduction in mortality rates among fetuses/newborns (≥37 weeks and birth weight ≥2500 g) whih decreased significantly from 5.1 per 1000 in 2006 to 3.6 per 1000 in 2013 (with 1.5 per 1000 or 29.4% reduction, 95% CI 0.6% to 2.4%; p=0.0015).19 The second study22 reported overall perinatal mortality reduction (52.8% in 2007 to 47.9% in 2008) before and after perinatal audit implementation but this difference was not statistically significant (table 3). Demonstrated changes were attributed to improved standards of care following implementation of stillbirth and neonatal death audits. No study reported newborn morbidity outcomes. One study21 reported a reduction in the incidence of maternal obstetric complications such as obstructed labour and antepartum haemorrhage, which contributes to stillbirths, following the implementation of a fresh stillbirth audit using standards as a benchmark (table 3).

Enablers and barriers of implementing stillbirth and neonatal death audits

Four studies9 23–25 reported enablers (table 4) and five studies9 23–26 reported barriers (table 5). In total, 18 enablers were identified with nine at the health provider level, seven at the facility level, and two at the national or regional system levels (table 4). Only one enabler at the health provider level was cited by more than one study (table 4). Twenty-three barriers were identified with one at the health provider level, 18 at the facility level and four at the national system levels (table 5). Eight barriers at a facility level and one barrier at a national level were cited by more than one study (table 5).

Table 4.

Enablers of implementing stillbirth and neonatal death audit

| Level | Enabler | Total | Citation |

| Health provider | Audit meetings provided opportunities for teaching and learning | 2 Studies | (9 24) |

| Confidentiality nature of discussion | 1 Study | (9) | |

| Positive atmosphere of voluntary participation and no blame | 1 Study | (9) | |

| Attendance of review meetings (p<0.001) | 1 Study | (25) | |

| Knowledge of objectives of MPDR (p<0.001) | 1 Study | (25) | |

| Observed improvement in maternal and newborn care (p<0.001) | 1 Study | (25) | |

| Strengthened responsibilities of the healthcare providers | 1 Study | (23) | |

| Documentation process of patient records enriched | 1 Study | (23) | |

| Facility providers committed to the process of reviewing | 1 Study | (24) | |

| Facility | Existence of MPDR committees (p<0.001) | 1 Study | (25) |

| Implementation of MPDR recommendations (p<0.001) | 1 Study | (25) | |

| Provision of feedback (p<0.001) | 1 Study | (25) | |

| Created a discussion platform of deaths | 1 Study | (23) | |

| Discovered gaps and challenges related to deaths | 1 Study | (23) | |

| Corrective measures were taken after audit | 1 Study | (23) | |

| Improved supervision and monitoring systems | 1 Study | (23) | |

| National | MPDR part of medical school curriculum | 1 Study | (24) |

| National and decentralised administrative levels were both engaged in the MPDR process | 1 Study | (24) |

MPDR, maternal and perinatal death review.

Table 5.

Barriers of implementing stillbirth and neonatal death audit

| Level | Barrier | Total | Citation |

| Health provider | Care providers not aware of actions implemented following audit recommendations | 1 Study | (26) |

| Facility | Health workers not aware of death audit process | two studies | (25 26) |

| Audit facility team members not trained | 3 Studies | (9 24 25) | |

| Inadequate supportive supervision | 1 Study | (25) | |

| Lack of financial motivation | 1 Study | (25) | |

| Increased workload in the ward | 3 Studies | (9 24 25) | |

| Too many cases to review | 2 Studies | (9 25) | |

| Inadequate formation and implementation of action plans | 4 Studies | (9 24–26) | |

| Poor documentation and poor information management systems | 2 Studies | (23 26) | |

| Cause of deaths not followed International Classification of Disease 10th version | 1 Study | (23) | |

| Inadequate human resource | 2 Studies | (9 23) | |

| Limited time led to the postponement of meetings | 3 Studies | (9 23 24) | |

| Lack of clarity in its intended purpose | 1 Study | (24) | |

| Weak analysis and discussion of the cases | 1 Study | (24) | |

| Lacks specific measurable action plan | 1 Study | (24) | |

| Lack of key hospital decision-makers in the audit committees | 1 Study | (26) | |

| Failure to disseminate audit reports to the national authorities | 1 Study | (26) | |

| Inadequate material resources (equipment for resuscitation) | 1 Study | (9) | |

| National | Reporting forms not systematically analysed at the national level | 1 Study | (24) |

| Technical committee meetings not held | 1 Study | (24) | |

| Funding guidelines not adequately disseminated | 1 Study | (24) | |

| Lack of broader engagement at the national level | 2 Studies | (9 26) |

Enablers

Most enablers (n=9) were identified at the health provider level. Audit meetings provided opportunities for teaching; learning was the only enabler mentioned by more than one study (table 4).9 24 The remaining enablers at both levels were mentioned by a single study (table 4). One study25 assessed the statistical significance of changes in enablers at both the health provider and facility levels. The enablers associated with statistical significant changes at the health provider level included attendance records of review meetings (p<0.001), knowledge of objectives of maternal and perinatal death review (MPDR) (p<0.001) and an observed improvement in care (p<0.001).25 Enablers identified at facility level included feedback (p<0.001), implementation of action (p<0.001) and the existence of an MPDR committee (p<0.001).25

Barriers

Out of 23 barriers identified at three levels by five studies,9 23–26 18 were identified at the facility level only (table 5). Barriers cited by more than one study at the facility level were inadequate formation and implementation of action plans9 24–26; audit facility team members not trained9 24 25; limited time led to the postponement of meetings9 23 24; increased workload in the ward9 24 25; health workers not aware of the death audit process25 26; too many cases to review9 25; poor documentation and inadequate information management systems23 26 and inadequate human resources (table 5).9 23 At the national level, a lack of broader engagement was the only barrier mentioned by more than one study (table 5).9 26

Discussion

This review has highlighted facility level barriers to audit that were common across studies including failure to implement action plans, inadequate training, limited time, increased workload, too many cases to review, poor documentation and inadequate information management systems. These findings will assist facility audit implementers and staff in identifying practical steps to improve the impact that audit has on reducing stillbirths and neonatal deaths.

Overall, the 10 studies included in this review support the key role that death audit plays in improving care and outcomes in perinatal and newborn care. Despite the identified barriers in this review, stillbirth and neonatal death audits resulted in improvements in facility structures, processes of care and neonatal health outcomes. We identified the following variables use of senior staff (obstetrician, paediatrician or senior nurse) to champion the audits at the facility, regular audit meetings with no blame approach, involvement of key decision-makers (doctors, nurses, health managers and administrators), implementing audit recommendations such as changes in physical structure of the ward, purchasing of essential supplies and equipment, training, staffing, and changing ward protocols and policies, suggesting that improvements need to be made in audit and service organisation to improve outcomes. More enablers have been identified at the health provider level while more barriers have been identified at the facility level. As the majority of barriers are related to the availability of staff to perform a death audit, our review has also shown that even auditing one death per week can be essential in identifying gaps in care.

This review adds to the latest evidence on how audits are performed, their outcomes on QoC and perinatal and neonatal health in LMICs. In addition, the present review has identified enablers and barriers and categorised them according to system levels to guide future implementers.

All included studies audited stillbirth and early neonatal deaths (0–7 days) except one study that included neonates from 0 to 28 days. Despite included studies resulted in significant improvement in care, it is essential to note that all studies were uncontrolled before and after studies. A review by Schouten et al28 found that uncontrolled before and after studies tend to exaggerate positive impacts as opposed to studies using a controlled design. With regard to the impact of audits on neonatal outcomes, only two studies reported newborn and perinatal mortality and no newborn morbidity outcomes were reported, suggesting this area could be explored further.

Stillbirth and neonatal death audit approaches

This review has shown the usefulness of both facility and external multidisciplinary teams in performing stillbirth and neonatal death audits. Further, criteria-based audits facilitate implementation of action plans and enable healthcare workers to evaluate standards at subsequent audits. Studies on maternal death audits reported that involving facility staff in the audit process promoted successful implementation, ownership and sustainability of the process.29 30 Most audits were conducted prospectively. The number of audited cases varied among the studies in this review, from a minimum of five cases to a maximum of 146 cases per month. Even though large numbers of cases reviewed may result in an in-depth analysis of gaps in care, such audit might pose a challenge in developing and implementing recommendations due to inadequate human and material resources in the LMIC context. In such contexts, it might be unrealistic to audit all stillbirths and neonatal deaths per month as these are often numerous. Depending on level of staffing and workload at the facility, it may be more practical for the mortality audit team to either review a selection of stillbirths and neonatal deaths or increase the frequency of meetings.6 Performing stillbirth and neonatal death audits at the departmental level is also essential in identifying gaps in care and interventions.

The majority of the approach activities were implemented at the facility level. Nambiar et al31 reported three system levels that are approached when implementing quality improvement initiatives. These are the microlevel (health providers), mesolevel (health facility team) and macrolevel (regional or national level). Despite all system levels being of value, facility level activities are central to the successful implementation of stillbirth and neonatal death audits. As described by Kaplan et al32 in their model of understanding success in quality, the facility level is responsible for quality improvement leadership, initiative support, senior leadership commitment, guidance and direction that shapes behaviour of staff pursuing quality improvement projects. Proper training of staff involved in death audits ensures quality implementation of audits and its recommendations. However, structural adjustments are required to facilitate the death audits. These adjustments include audit team characteristics, workforce focus, resource availability and data infrastructure that exist across all system levels to trigger and influence the success of death audit processes.32

While at the health provider level, the participation of individual staff is essential in the audit process, a single motivated care provider who has the capability and desire to improve performance will be of great value to the system.32 National or regional level activities like regulation, tool development, governance and dissemination need continuous coordination, as they act as external motivators that stimulate the organisation to improve the performance in death audit or any quality improvement projects.32

Outcomes of stillbirth and neonatal death audits

A previous systematic review on effects of perinatal mortality audits in LMICs reported a reduction in perinatal mortality of 30% (95% CI 21% to 38%) after the introduction of facility-based perinatal audits.8 However, this previous review focused on perinatal mortality audits (stillbirths and early neonatal deaths, 0–7 days old), which may miss late neonatal death audits or early neonatal deaths occurring in neonatal wards after discharge from the labour ward, which might give a false impression about overall neonatal mortality audits (age 0–28 days). The current review retrieved the latest evidence on outcomes of stillbirth and neonatal death audits. Overall findings varied both within and between studies. Most of the articles reported a mixture of outcomes that fell into the category of structure, process and health outcomes. Only one study reported a significant decrease in newborn mortality.

Enablers and barriers to implement stillbirth and neonatal death audits

Identification of enablers and barriers are essential for hospital management and programme planners to implement successful stillbirth and neonatal death audits that improve the QoC. In this review, 18 enablers and 23 barriers were identified at three levels, with more enablers (9) cited at the health provider level and more barriers (18) cited at facility level. Similar barriers have been reported in the previous review on maternal and perinatal death audits.7 Hospital management should prioritise both enhancing enablers identified at the health provider level to maintain staff morale and resolving barriers at facility level as they demotivate staff involved in audits to effect change. In their review, Nyamtema et al26 found that other facilities had discontinued audit meetings due to the failure of hospital management to implement audit recommendations.

Limitations

The current systematic review has some limitations, mainly relating to scope. Although the present review assembled evidence from seven different countries, located in four different regions (sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Europe/Central Asia and East Asia and Pacific), the published research included in this review was limited since only 10 studies were identified, thus, potentially limiting generalisability. Our search was limited to literature describing approaches, enablers, barriers or reporting outcomes of stillbirth and neonatal death audits at the facility level and to English language papers only. This limited search might have missed information regarding other elements of death audits and also studies reported in other languages. Five articles could not be retrieved, which may have included important additional information to the review. Our search only included original research articles; more information may be available in the grey literature, organisation reports, reviews, dissertations and theses, and conference proceedings. Although two authors conducted screening and eligibility assessment, data extraction and quality appraisal were primarily conducted by one author, which might have led to selection bias. However, where there was uncertainty, the second author was approached.

Conclusion

Implementation of stillbirth and neonatal death audits improves structure, process and health outcomes in maternal and neonatal care. Using a multidisciplinary facility team to conduct audits contributes to the success of the process. Despite all system levels being of value, facility-level activities are central to the successful implementation of stillbirth and neonatal death audits. Even auditing a single death is useful in the process of improving care at the facility level. Completing the audit cycle by implementing recommendations is crucial to improving perinatal outcomes. The indemnification of both audit enablers and barriers can help hospital management to improve audit processes. Researchers should aim at generating more evidence on how to implement stillbirth and neonatal death audits effectively, including sustaining the practice in oder to further improve its impact on newborn outcomes in LMICs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alison Derbyshire from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine library department for support during this review. We would also like to thank the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission for financial support and Lyle Taylor for editing the manuscript. We would like to thank Dr Lazzerini and other coauthors for allowing us to adapt table templates from their systematic review published in BMJ Open Journal, 2018.

Footnotes

Contributors: MJG conceived the idea of the study. MJG and JMM carried out data extraction. All authors (MJG, JMM, MA, ND and SA) were instrumental in the study’s development, in reviewing drafts of the paper and in approval of the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the ‘Commonwealth Scholarship Commission’ (MWCSC, 2018, 802). This paper is part of first authors PhD studies.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-Quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1196–252. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD, W.H.O . World bank group, delivering quality health services: a global imperative 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.UN IGME, Levels & Trends in Child mortality Report 2020, UNICEF, et al., Editors. 2020: New York, US.

- 4.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 2016;387:587–603. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e98–108. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00275-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization, . Making every baby count: audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Geneva: WHO Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lusambili A, Jepkosgei J, Nzinga J, et al. What do we know about maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity audits in sub-Saharan Africa? A scoping literature review. Int J Hum Rights Healthc 2019;12:192–207. 10.1108/IJHRH-07-2018-0052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pattinson R, Kerber K, Waiswa P, et al. Perinatal mortality audit: counting, accountability, and overcoming challenges in scaling up in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;107 Suppl 1:S113–22. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandakabatu M, Nasi T, Titiulu C, et al. Evaluating the process and outcomes of child death review in the Solomon Islands. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:archdischild-2017-314662–90. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Bank . New country classifications by income level: 2019-2020, W.B.D. team, editor. 2019, world bank: data Blog.

- 12.Leatherman S, Ferris TG, Berwick D, et al. The role of quality improvement in strengthening health systems in developing countries. Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:237–43. 10.1093/intqhc/mzq028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aminu M, Unkels R, Mdegela M, et al. Causes of and factors associated with stillbirth in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. BJOG 2014;121 Suppl 4:141–53. 10.1111/1471-0528.12995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halim A, Aminu M, Dewez JE, et al. Stillbirth surveillance and review in rural districts in Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:224. 10.1186/s12884-018-1866-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belizán JM, McClure EM, Goudar SS, et al. Neonatal death in low- to middle-income countries: a global network study. Am J Perinatol 2012;29:649–56. 10.1055/s-0032-1314885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002;12:1284–99. 10.1177/1049732302238251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruk M, Gage A. Synthesizing improvement approaches, in Lancet global health high quality health systems in the sustainable development goal era (HQSS) Commission inception meeting 2017.

- 18.Demise A, Gebrehiwot Y, Worku B, et al. Prospective audit of avoidable factors in institutional stillbirths and early neonatal deaths at Tikur Anbessa hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health 2015;19:78–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stratulat P, Curteanu A, Caraus T, et al. The experience of the implementation of perinatal audit in Moldova. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2014;121: :167–71. 10.1111/1471-0528.12996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidanto HL, Mogren I, van Roosmalen J, et al. Introduction of a qualitative perinatal audit at Muhimbili national Hospital, Dar ES Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:45. 10.1186/1471-2393-9-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasengele CT, Mowa R, Katai C, et al. Factors contributing to intrapartum stillbirth: a criteria-based audit to support midwifery practice in Zambia. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health 2017;11:67–71. 10.12968/ajmw.2017.11.2.67 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakibuuka VK, Okong P, Waiswa P, et al. Perinatal death audits in a peri-urban hospital in Kampala, Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2012;12:435–42. 10.4314/ahs.v12i4.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biswas A, Rahman F, Eriksson C, et al. Facility death review of maternal and neonatal deaths in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141902. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong CE, Lange IL, Magoma M, et al. Strengths and weaknesses in the implementation of maternal and perinatal death reviews in Tanzania: perceptions, processes and practice. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:1087–95. 10.1111/tmi.12353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agaro C, Beyeza-Kashesya J, Waiswa P, et al. The conduct of maternal and perinatal death reviews in Oyam district, Uganda: a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2016;16:38. 10.1186/s12905-016-0315-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyamtema AS, Urassa DP, Pembe AB, et al. Factors for change in maternal and perinatal audit systems in Dar ES Salaam hospitals, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:29. 10.1186/1471-2393-10-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazzerini M, Richardson S, Ciardelli V, et al. Effectiveness of the facility-based maternal near-miss case reviews in improving maternal and newborn quality of care in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019787. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schouten LMT, Hulscher MEJL, van Everdingen JJE, et al. Evidence for the impact of quality improvement Collaboratives: systematic review. BMJ 2008;336:1491–4. 10.1136/bmj.39570.749884.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weeks AD, Alia G, Ononge S, et al. A criteria-based audit of the management of severe pre-eclampsia in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005;91:292–7. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mgaya AH, Kidanto HL, Nystrom L, et al. Improving standards of care in obstructed labour: a Criteria-Based audit at a referral hospital in a low-resource setting in Tanzania. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166619. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nambiar B, Hargreaves DS, Morroni C, et al. Improving health-care quality in resource-poor settings. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:76–8. 10.2471/BLT.16.170803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, et al. The model for understanding success in quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:13–20. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjoq-2020-001266supp001.pdf (211.2KB, pdf)