Abstract

Strategies that facilitate change to policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) changes can enable behaviors and practices that lead to cancer risk reduction, early detection, treatment access, and improved quality of life among survivors. Comprehensive cancer control is a coordinated collaborative approach to reduce cancer burden and operationalizes PSE change strategies for this purpose. Efforts to support these actions occur at the national, state, and local levels. Resources integral to bolstering strategies for sustainable cancer control include coordination and support from national organizations committed to addressing the burden of cancer, strong partnerships at the state and local levels, funding and resources, an evidence-based framework and program guidance, and technical assistance and training opportunities to build capacity. The purpose of this paper is to describe the impact of public policy, public health programming, and technical assistance and training on the use of PSE change interventions in cancer control. It also describes the foundations for and examples of successes achieved by comprehensive cancer control programs and coalitions using PSE strategies.

Keywords: Comprehensive cancer control, Policy, Coalitions, Systems change

Introduction

Evolution and growth of support for PSE change strategies in cancer control

In 1994, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and several leading national organizations developed a coordinated, collaborative approach that leverages the strengths and expertise of key stakeholders to address the burden of cancer in the United States [1]. Comprehensive cancer control (CCC) harnesses the power of coalitions and supports the development and implementation of data-driven plans that aim to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by cancer [1-3]. The foundation for policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) change in cancer control was laid in 1998 when the CDC provided support to six CCC programs that forged partnerships to engage in strategies that promoted improvements in prevention, early detection, treatment access, and improved quality of life among cancer survivors [1, 4, 5].

Strategies that support changes to policies, systems, and the environment can have broad impact on public health and can help address the chronic disease burden [6, 7]. These strategies include activities designed to inform decision-makers and the public about the health impact of policies or regulations and modify the environment to increase access to healthy choices [6, 7]. Early on CCC programs and coalitions used strategies to support efforts to reduce smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke, increase access to healthy foods in school lunch programs, and promote physical activity by facilitating the inclusion of physical education in school curricula [4]. The commitment to improving health outcomes through PSE change continued with more CCC programs and coalitions prioritizing initiatives across the cancer continuum, from prevention through survivorship [5].

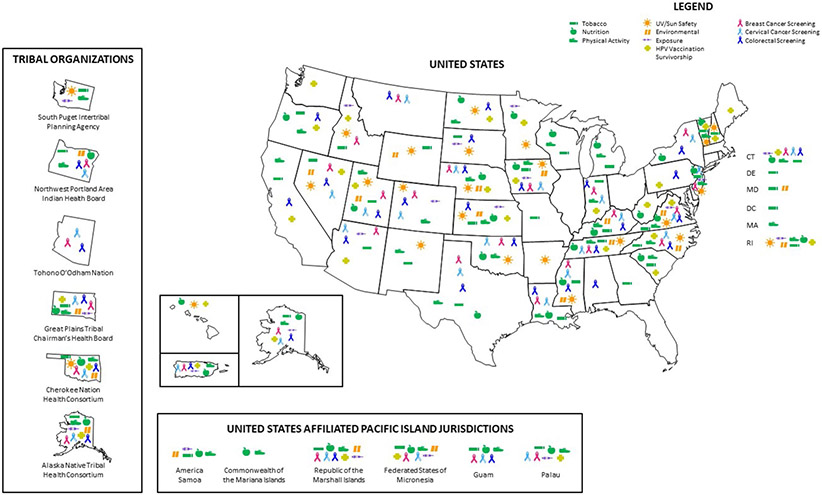

Over the past 20 years, the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (NCCCP) has grown to support all 50 states, District of Columbia, tribal organizations, territories, and Pacific Island Jurisdictions (PIJs) [3]. These programs work with large partnership networks and coalitions and provide the data needed to support PSE change. This paper describes the impact of public policy, public health programming, and technical assistance and training (TAT) on the use of PSE change interventions in cancer control. It also describes the foundations for and examples of successes achieved by CCC programs and coalitions.

Factors for successful PSE change strategies

Public health strategies can inform laws, regulations, or guidelines that impact health and enhance clinical care by transforming health systems at various levels. These strategies modify the physical, social, or economic environments to promote healthy behaviors among populations, and have the greatest potential to impact disease burden [7]. The Health Impact Pyramid is a useful framework that describes the impact of different types of public health interventions such as health education and counseling; clinical interventions that confer long-term protection; direct clinical care; PSE change strategies; and efforts that seek to impact social determinants of health on disease burden [7]. PSE change strategies that improve health outcomes depend on a strong foundation of strategic alliances, organizational capacity, and reliance on data and evidence for planning and demonstration of outcomes through evaluation.

Forging and Supporting strategic alliances through comprehensive cancer control coalitions

The typical PSE approach is community-centered, fostering relationships with health care organizations, businesses, media, academia, and community-based organizations. It enables community stakeholders to form coalitions with a shared mission of reducing disease burden in their communities and allows for a bottom-up approach to public health policy [8]. CCC programs and coalitions have a long history of building relationships to sustain PSE strategies that address cancer [4, 5]. The power of these collaborative actions has been documented in assessments of the NCCCP awardees and a special demonstration project that provided resources to CCC programs specifically to help with utilizing PSE change strategies [3, 9, 10]. CCC coalitions and their chronic disease partners have worked collaboratively to improve public health using effective and evidence-based PSE change efforts [3-5, 9, 10].

Coalitions engaged in PSE change efforts require resources and support for conducting cancer-related community needs assessments, building relationships, program planning, implementation, and evaluation. Resources integral to building capacity to implement and sustain these efforts include dedicated, competent staff; strong partnerships at the state and local levels; an evidence-based framework and program guidance focused on PSE change strategies; and TAT opportunities [9, 10]. A recent evaluation of a 5-year demonstration project of CCC programs determined that staff members whose time was devoted to PSE efforts and who had an understanding of these processes and partnership sustainability greatly improved the program and coalitions’ capacity to implement PSE change strategies [9, 10].

Governmental and non-governmental organizations alike have provided tools, resources, and systems to support PSE change efforts as well as developed systems to provide TAT to program implementers and their partners that address a multitude of health related issues such as access to care, tobacco prevention, cardiovascular disease, and cancer prevention and control [4, 8, 11, 12].

Coalition efforts are supported by the CDC and the Comprehensive Cancer Control National Partnership (CCCNP), which strive to coordinate efforts at the national level and assist coalitions in developing, implementing, and evaluating their efforts [1, 4, 5]. The CCCNP is a network of nineteen leading cancer organizations committed to supporting CCC programs and coalitions through the coordination of national efforts and the provision of TAT [13]. For the past 20 years, the CCCNP has leveraged the expertise of each member organization, engaged in information sharing that reduces duplication and creates synergy among member organizations, convened policy and practice summits for CCC programs and coalitions, and developed a TAT agenda that is based on CCC program and coalition needs [5]. These combined efforts have supported both the CCC programs and their coalitions, whose networks consist of a diverse group of partners who are uniquely positioned to implement these strategies.

Technical assistance and training to support PSE change efforts

The provision of TAT can greatly increase coalition capacity to implement PSE change efforts [14, 15]. These opportunities are delivered in multiple ways including but not limited to written guidance documents, coaching, peer-to-peer learning, emails, web-based support, webinars, or face-to-face learning opportunities [14]. To further bolster these efforts, CDC engaged in cooperative agreements with the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the George Washington University (GW) Cancer Center to provide TAT in using PSE approaches among other areas [16]. ACS, GW Cancer Center, and the CCCNP have collaborated to design TAT opportunities to enhance, accelerate, and extend the reach of PSE change interventions for sustainable cancer prevention and control.

Members of the CCCNP have worked collaboratively and independently to provide TAT to support CCC programs and coalitions in executing PSE strategies, as detailed in Table 1. For example, the CCCNP, ACS, and CDC produced two guidance documents, one providing general information on applying the PSE change approach in CCC and the second focused on engaging the media in educating the public about the health impact of such approaches. The partnership, led by ACS and CDC, has also held in-person trainings and action planning workshops focused on skill-building for the appropriate use of PSE strategies, as well as colorectal cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, and tobacco control workshops that also provide an overview of successful PSE change interventions for each public health issue. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) developed a resource guide specific to the Health in All Policies approach, which is a collaborative approach that integrates and articulates health considerations into policymaking across sectors to improve the health of all communities and people. CDC provides a number of resources including an online course on policy evaluation methodology and a health system change online planning tool. In collaboration with GW Cancer Center, CDC released several resources that coalitions can use to enhance liver cancer prevention through PSE change efforts around viral hepatitis. Through their cooperative agreement with CDC to provide TAT, GW Cancer Center produced several additional tools that support PSE efforts. Action4PSEChange.org is an online tool that provides step-by-step explanations of and curated resources for the PSE change process as applied in cancer control. GW Cancer Center also developed Action for PSE Change: A Training, a self-paced, no-cost online course that provides a solid foundation in the PSE change approach for new CCC professionals and an update on evidence and examples for seasoned professionals. GW Cancer Center has also released resources in the past few years that support PSE strategies in the areas of HPV vaccination uptake and patient navigation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of national efforts to support cancer prevention and control policy

| Focus | Description | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Public policy/advocacy | ||

| American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (non-CDC funded) | National organization that mobilizes local volunteers to address: prescription drug affordability, quality of life among cancer survivors, tobacco control, cancer research funding, access to health care, and prevention of cancer deaths | https://www.acscan.org/ |

| One voice against cancer (non-CDC funded) | Network of national non-profit organizations that addresses funding for cancer research and control programs | https://ovaconline.org/ |

| Grant opportunities/programmatic support | ||

| National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program | Public health program administered by CDC that supports all 50 states, several tribes and tribal organizations, territories, and Pacific Island jurisdictions. Funded programs work with comprehensive cancer control coalitions on primary prevention, screening and early detection, and addressing the needs of cancer survivors | https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/ |

| Demonstrating the capacity of comprehensive cancer control programs to implement policy and environmental cancer control interventions | Public health program administered by CDC from 2010–2015 that supported 13 National Comprehensive Cancer Control programs: Cherokee Nation, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, University of Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, Utah, and Wisconsin to work collaboratively with partners to help advance cancer prevention and control efforts by implementing policy, systems, and environmental change interventions | N/A |

| National support to enhance implementation of comprehensive cancer control activities | Public health program administered by CDC to facilitate the provision of high-quality technical assistance and training to comprehensive cancer control programs by national organizations with subject matter expertise. Technical assistance and training providers funded under this program aim to build program capacity that ensures implementation of CCC plan activities at the local level, effective implementation of PSE strategies, sustainable partnerships, and promotion of CCC program successes | https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/dp13-1315.htm |

| Technical assistance and training | ||

| American Cancer Society PSE change resource guide |

Guidance document for comprehensive cancer control programs and coalitions that provides resources, program models, and tools that assist program planners with the development and implementation of a policy, systems, and environmental change agenda | https://bit.ly/PSEResourceGuide |

| American Cancer Society Policy, systems, and environmental change: effectively engaging your coalition when working with the media |

Guidance document for comprehensive cancer control programs, coalitions, and policy-focused committees that describe ways to effectively use media to inform policy, systems, and environmental change strategies | https://bit.ly/CCCNPPSEMediaGuide |

| American Cancer Society Smoke-free public housing workshop | One-and-half-day in-person workshop in which participants acquired skills necessary to implement action plans that facilitated the implementation of a new HUD landmark smoke-free policy aimed at providing a smoke-free environment for public housing residents | https://www.cccnationalpartners.org/new-resources-smoke-free-public-housing-workshop |

| American Cancer Society overview of policy, systems, and environmental change | Web-based information presented on YouTube platform that provides an introduction to policy, systems, and environmental change strategies | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJZ9CewtuPA |

| Association of state and territorial health officials health in all policies: strategies to promote innovative leadership | Resource guide to educate and empower public health leaders to promote a Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach to policymaking and program development | https://www.astho.org/Programs/Prevention/Implementing-the-National-Prevention-Strategy/HiAP-Toolkit/ |

| Centers for disease control and prevention introduction to policy evaluation in public health | Web-based course that introduces public health practitioners to the use of policy evaluation in public health and provides specific instruction on applying evaluation methods throughout a policy process | https://www.train.org/main/course/1064948/ |

| Centers for disease control and prevention leading through health system change planning tool | Online planning tool to assist public health practitioners with developing and implementing health systems transformation activities by following a five step process | https://ghpc.gsu.edu/leading-health-system-change-public-health-opportunity-planning-tool/ |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & George Washington University Cancer Center Strategies to Reduce Viral Hepatitis-Associated Liver Cancer |

Summary of a National Academy of Sciences report and companion worksheet that allows policy makers and the cancer community address viral hepatitis-related liver cancer |

https://bit.ly/ViralHepNAMSummary2018 https://bit.ly/ViralHepWorksheet2018 |

| George Washington University Cancer Center Viral Hepatitis and Liver Cancer Prevention Profiles | To help improve policy makers and cancer control professionals’ awareness of viral hepatitis risk factors and evidence-based prevention strategies. The George Washington University Cancer Center, in collaboration with CDC, developed educational materials on viral hepatitis and liver cancer. By accessing the map, policy makers and cancer control professionals will find state profiles on viral hepatitis and liver cancer statistics that can be used when communicating with clinicians and stakeholders | https://bit.ly/ViralHepProfiles |

| These state-specific and general profiles help improve policy makers and cancer control professionals’ awareness of viral hepatitis risk factors and evidence-based prevention strategies, including PSE strategies to reduce the burden of viral hepatitis and liver cancer nationwide | ||

| George Washington University Cancer Center Action4PSEChange.org | This online tool provides an explanation of each step of the PSE change process and highlights PSE change success stories from CCC programs nationwide. The tool also provides an extensive list of resources for planning and implementing PSE change | https://action4psechange.org/ |

| George Washington University Cancer Center Action for PSE Change: A Training |

This no-cost online course thoroughly explores PSE change from its evidence base to a full-length case study. The training provides background information on the PSE change process, a PSE action plan template, real-world examples and suggests theoretical and evaluation approaches to help grow the PSE change evidence base | https://cancercenter.gwu.edu/for-health-professionals/training-education |

| George Washington University Cancer Center Seven Steps for Policy, Systems and Environmental Change: Worksheets for Action |

This resource is a companion to both Action4PSEChange.org and the accompanying Action for PSE Change: A Training. The worksheets assist CCC professionals in planning, designing, implementing and evaluating PSE change initiatives. Each covers one of the seven steps of the PSE change process | https://bit.ly/GWCCPSEResourceGuide |

| George Washington University Cancer Center HPV Cancer and Prevention Profiles |

These state HPV cancer and prevention profiles include data on HPV-attributable cancers as well as a state-specific snapshot of HPV-associated cancers and vaccination rates | https://bit.ly/HPVFlyers2017 |

| George Washington University Cancer Center Advancing the Field of Cancer Patient Navigation: A Toolkit for CCC Professionals |

This toolkit guides CCC programs in advancing patient navigation and can be used to educate and train patient navigators, provide technical assistance to coalition members, build navigation networks, and identify policy approaches to sustain patient navigation programs | https://bit.ly/PNPSEGuide |

| George Washington University Cancer Center Implementing the Commission on Cancer Standard 3.1 Patient Navigation Process |

This road map guides the community needs assessment team in designing a patient navigation process that navigates cancer patients through their care and addresses barriers facing patients, caregivers, and communities in the cancer program’s catchment area | https://bit.ly/CoCPNRoadMap |

Other TAT includes training workshops. In December 2016, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) published a final rule for each Public Housing Agency (PHA) administering low-income, conventional public housing to initiate a smoke-free policy. The effective date of the Rule was 3 February 2017, but the Rule provided an 18-month implementation period for all PHAs to put into place a smoke-free policy by 31 July 2018. In September 2017, the ACS, CDC, and the HUD with the support of nine national partner organizations hosted a Smoke-Free Public Housing (SFPH) Workshop for CCC coalitions and their PHA partners to learn about effective strategies to plan, implement, and promote a SFPH policy prior to the July 31 implementation deadline. ACS and its partners continue to provide CCC coalitions technical assistance on the implementing the SFPH policy and supporting the coordination of tobacco cessation services for PHA residents who may need assistance in quitting tobacco use. These TAT opportunities sought out to bolster public health programs that worked in collaboration with multi-sector coalitions to inform and support this public health policy.

Cancer control programming: grant opportunities and programmatic support

The CDC has provided programmatic support to CCC through the NCCCP and a PSE demonstration program for sustainable comprehensive cancer control. The NCCCP provides the funding, science, and guidance that national organizations, health departments, health systems, and their partners need to plan, implement, and evaluate cancer control plans and interventions. While working with coalitions to facilitate PSE change efforts was an early strategy of the NCCCP, in 2010 the program identified six major priority areas (i.e., emphasize primary prevention, promote early detection and treatment, support cancer survivors and caregivers, build healthy communities through PSE approaches, achieve health equity for cancer prevention and control, and demonstrate outcomes through evaluation) for awardees to focus on to maximize their program efforts and achieve long-term outcomes [2]. These priorities are essential to the effective implementation of strategies to address cancer across the continuum. The current NCCCP started in June 2017 and retains many of the program components successfully implemented over the past 20 years. The program emphasizes the importance of collaboration with cancer registries, screening programs, and other chronic disease prevention programs; partnership networks necessary to support the implementation of cancer program priorities and activities; and evidence-based interventions to facilitate community-clinical linkages, health systems change, and environmental approaches that promote healthy living [17].

From 2010 to 2015, 13 of the 65 CCC programs received additional funding through a cooperative agreement to develop and implement a PSE agenda, in collaboration with their cancer coalitions, to address the burden of cancer in their communities. In addition to funding, demonstration sites received technical assistance and a framework to inform and support PSE change efforts from the CDC and the CCCNP. Demonstration sites increased their capacity to use a PSE approach by employing a subject matter expert knowledgeable in these approaches, enhancing interactions with both traditional and non-traditional partners in workgroup setting, focusing on evidence-based strategies as prescribed in a PSE agenda, educating key stakeholders, implementing a media plan, and facilitating program improvement through careful documentation and analysis of outcomes [18].

Using data and evaluation to demonstrate outcomes

Executing PSE strategies requires a comprehensive understanding of the state of the science surrounding the specific public health issue. The interaction between research and policy is bi-directional; research must take into account empirical evidence and contextual factors (such as the social, economic, and political environment) and policy action should be data-driven [19-21]. Organizations implementing PSE change efforts need to have the capacity to collect, analyze, and disseminate information that has the potential to impact public health issues [11, 19, 22]. It is also important to gather evidence on the health impact of PSE change efforts in the community.

This complex system in which multiple players may influence health through PSE change must be evaluated in order to document outcomes, identify best practices, and establish a strong evidence base. There are many frameworks and tailored methods that can be used to assess achievement of outcomes at the system, coalition, and advocate levels while taking into consideration the complex nature of policy development and implementation [23]. For example, engaging multiple and diverse stakeholders is an element of the CDC framework for planning and implementing practical program evaluation [23, 24]. Additionally, evaluators have developed tailored instruments to assess changes in organizational capacity, collective impact of coalitions, and decision-maker support for a particular issue or policy [25].

There are many considerations regarding the framing and focus of evaluating the effectiveness of PSE strategies. Challenges persist such as stakeholders’ interest in longer-term outcomes and whether the desired resources were available, decision-maker support was maintained, as well as PSE contribution to distal health outcomes [25]. In these situations, it is important to focus on the interim or near-term outcomes of an initiative, such as coalition capacity and effectiveness, and the reach and intensity of their efforts [25]. While direct measurement of distal outcomes is not always feasible, modeling can be used to give a sense of more salient and longer-term outcomes. These challenges notwithstanding, a mixed methods evaluation over the life cycle of the NCCCP has begun to elucidate the collaborative nature of federally funded programs and multi-sector partnerships in their development of an agenda that ensures effective implementation of PSE change strategies across the cancer continuum [3]. The review of this coordinated and collaborative approach to support PSE change strategies and the national efforts that bolster this work has given rise to viable models for sustainable cancer prevention and control.

Moving to practice: National, state, and local efforts to inform policy change efforts

Efforts to influence cancer prevention and control policy

At the national level, multi-sector partnerships and policy organizations work collaboratively to educate and inform decision-makers at all levels of government on evidence about: the behaviors that influence cancer risk or lead to earlier detection, factors influencing access to and quality of treatment, and programs that are needed to improve the quality of life among cancer survivors. In addition to this, decision-makers are educated on the knowledge base about resources needed to establish and sustain a program and a research agenda that impacts the cancer control continuum. Programmatic efforts include the administration of federal grants and cooperative agreements that provide financial resources and support to entities implementing PSE change strategies or building organizational capacity to support this work.

Informing public health policy

Informing decision-makers and the public about the likely effects of these strategies is an important component of PSE initiatives. There have been several national, state, and local evidence-based policies or strategies implemented that can improve public health (see Table 2)—These have included but are not limited to the elimination of lead in commercial products, seat belt regulation, and water fluoridation [7].

Table 2.

Summary of Comprehensive Cancer Control Policy, System, and Environmental Change Efforts

| Focus | Description | Policy outcome |

|---|---|---|

| State program examples | ||

| Primary prevention | ||

| Tobacco prevention and control | Smoke-free air ordinance Tobacco taxation |

Increased number of people in smoke-free and vape-free schools, parks, worksites, and businesses Prompt current smokers to quit and prevent youth initiation, as well as utilization of revenue to fund public health initiatives |

| Nutrition | Community gardens Healthy vending policy |

Increase access to healthy foods Reduce consumption of unhealthy foods and promote good nutritional choices |

| UV exposure | Indoor tanning | Reduction in minors’ access to indoor tanning through policies that use age restrictions, require parental consent, and/or require parental accompaniment |

| Physical activity | Safe Routes to Schools Dual Use Agreements Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan |

Alter the built environment and/or increase access to spaces to promote physical activity |

| HPV vaccination | Health system wide interventions | Increase vaccination uptake among 11–12 year olds |

| Early detection and screening | ||

| Employer Cancer Screening | Increase access to screening by reducing structural barriers | |

| Medicaid Reimbursement | Increase access to screening by reducing patient costs | |

| Patient Navigation | Improve access to screening through care coordination | |

| Survivorship | ||

| Survivorship Care Planning | Improve and promote preventive health behaviors among cancer survivors | |

| Tribal program examples | ||

| Primary prevention | ||

| Tobacco prevention and control | Smoke-free air ordinance Tobacco taxation |

Smoke-free workplaces and casinos Reduction of smoking prevalence in youth, reduction of smoking prevalence in adults |

| Nutrition | Learn to Grow | Promotion of healthy eating among young children in childcare homes, increased access to foods by harvesting vegetables grown in childcare home gardens, and increased access to foods by supporting famers’ markets |

| Early Detection and Screening | ||

| Patient Navigation | Reduce barriers associated with cancer screening through education and care coordination | |

| Employee Cancer Screening | Use of administrative leave or flextime to encourage employees to get cancer screening | |

| Patient Reminder Systems | Increase community demand and access to cancer screening | |

| Pacific Island Jurisdiction program examples | ||

| Primary prevention | ||

| Tobacco prevention and control | Smoke-free air ordinance Tobacco taxation |

Smoke-free schools, worksites, public places Reduction of tobacco consumption among adults and youth, allocation of revenue to non-communicable disease prevention activities |

| Betel nut use | Betel nut ban | Restrictions banning use among individuals under the age of 19 |

| Ban use in schools, workplaces, and places were health care services are being offered | ||

| Nutrition | Farm to Table | Increase access to healthy foods |

| HPV vaccination uptake | HPV Program in Schools | Increase vaccination uptake in adolescents through mandates within school systems |

| Alcohol consumption | Alcohol tax | Reduction of alcohol consumption and increased resources to non-communicable disease prevention activities |

As it relates to cancer control, public health policy actions may be facilitated through cancer organizations and large partnership networks. Organizations supported by federal funding cannot advocate or lobby for policy change; however, other organizations can use their own or other funding to promote cancer prevention and control. There are several national groups who remain committed to this effort. Established in 2001, the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN), the non-profit, non-partisan advocacy affiliate of the American Cancer Society (ACS), educates the public, elected officials, and candidates about cancer’s toll on public health and encourages them to make cancer a top priority. ACS CAN staff and volunteers are active members of CCC coalitions, supporting a wide range of initiatives and activities to reduce the burden of cancer in states, tribes, territories, PIJs, and local communities through evidence-based public policy and advocacy engagement. Leveraging its knowledge, experience, and organizational resources, ACS CAN enhances and advances CCC efforts to take an organized, community-based approach to inform and influence policy change at all levels of government.

Two examples of ACS CAN’s support of PSE change are its role as organizer and convener of One Voice Against Cancer (OVAC) and its support of state-level funding for breast and cervical cancer in every state. OVAC is a collaboration of national non-profit organizations that represent millions of Americans. It delivers a unified message to Congress and the White House on their desire for federal investment in cancer prevention and control programs and research funding. Through its diverse member organizations, OVAC is uniquely positioned to enhance the cancer community’s ability to help those facing cancer to battle this deadly disease.

At the state level, ACS CAN’s staff convened roundtables throughout Nevada, to bring together diverse stakeholders including cancer control leadership, health systems partners, legislators, and other key breast and cervical cancer champions to discuss opportunities to address known barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening, diagnostic testing, and treatment services. A constant theme throughout these discussions was supporting and broadening the reach of the Nevada’s Women’s Health Connection (WHC), the state’s Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (BCCEDP) which relied solely on CDC funding and private donations. Nearly every year, WHC had to turn eligible women away from the program, ultimately denying them access to timely and appropriate cancer screening and early detection services. Through these convenings and other briefings, ACS CAN successfully educated these key stakeholders, and in 2017, the Senate and Assembly included $1 million in state funds to support the WHC program for the 2018–2019 biennial budget. As a result, thousands of Nevada women gained access to a broad range of life-saving breast and cervical cancer services.

Successful comprehensive cancer control program and coalition PSE efforts

Through federal programmatic support and TAT, CCC programs and coalitions have successfully used PSE change strategies to improve public health. During the 2012–2017 NCCCP program period, CCC programs reported which cancer prevention and control issues were addressed using PSE strategies. Figure 1 illustrates the most commonly reported cancer control issues addressed through these strategies. As it relates to tobacco control, 65% of state programs reported using PSE strategies to affect change. Approximately 50% of state programs addressed barriers to healthy nutrition and physical activity. Programs also reported efforts related to breast (42%), cervical (38%), and colorectal (50%) cancer screening. Forty-seven percent of tribal programs reported using PSE change strategies to address tobacco control, physical activity, colorectal cancer screening, breast cancer screening, and cervical cancer screening. All PIJs used PSE strategies to address nutrition and physical activity, tobacco control, breast cancer screening, and cervical cancer screening.

Fig. 1.

Top ten public health issues most commonly addressed by policy, system, and environmental change strategies 2012–2015

Additionally, data reported by CCC programs as part of the NCCCP reporting guidelines, document review of conference proceedings and workshop summaries sponsored by the CCCNP, and submitted success stories were reviewed to characterize PSE change strategies implemented from 2012 to 2017. Table 2 summarizes key PSE strategies implemented by CCC programs and coalitions that have addressed issues across the cancer control continuum in states, tribes, territories, and PIJs. CCC programs and coalitions engage in PSE change approaches across the cancer continuum from prevention through to palliative care and survivorship.

Cherokee Nation successfully educated local leaders about the health effects of smoke-free schools to combat the increasing rate of youth tobacco use in public schools. Their effort was informed by data and a contextual assessment that led them to leverage competition between schools to increase the number of schools that became smoke free.

The Smoke-free New Orleans Coalition also had success in local tobacco control, using creative communications and media promotion to educate the public and decision-makers about the health impact of making indoor workplaces and public spaces smoke free. A 2015 ordinance now ensures smoke-free environments in bars, casinos, and other public spaces.

A successful partnership between Utah Cancer Control Program, the Utah Department of Transportation, and the Chronic Disease Program led to increased accessibility of bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, creating safer environments for physical activity.

South Dakota’s CCC program worked with a large health system to implement evidence-based systems approaches to increasing HPV vaccination, leading to 100,000 client reminders being distributed and more than 13,000 doses of HPV vaccine administered in the first 2-year period.

Other prevention successes include New York’s efforts to expand employer adoption of paid leave policies for cancer screenings; Iowa’s radon-free homes initiative; Michigan and Indiana’s work to challenge and recognize employers to increase cancer prevention; and Kentucky’s efforts to establish a colon cancer screening program fund. Across the cancer continuum, coalitions have seen other successes. Washington, DC successfully worked to improve access to chemotherapy for Medicaid patients; Florida developed a certification program for community health workers to increase the workforce; and Georgia supported expanding access to palliative care statewide through the creation of a Palliative Care Council. These examples exhibit the power of CCC programs and coalitions who over the past 20 years have successfully leveraged their resources and combined expertise to help affect policy, systems, and environmental change across the United States.

Summary and recommendations

This paper describes a pathway to sustainable cancer prevention and control using PSE change approaches. While complex and multi-faceted, PSE changes have resulted in measurable improvements in adoption of healthy behaviors that reduce cancer risk, access to screening, and lifestyle supports for cancer survivors. Coalitions and partnerships are a necessary component for PSE change, but they are also an important outcome. Coalitions and partnerships make it possible to leverage resources, expertise, and sustain capacity to impact population-level public health. National-, state-, and local-level strategies can lead to significant gains in other public health arenas, as well as support an ongoing mechanism for continued change.

A strong foundation has been laid whereby PSE change strategies can be successfully deployed in other arenas related to cancer control. For example, CCC programs and coalitions are uniquely positioned to implement PSE change strategies that will have a lasting impact on reducing the death and disability caused by upstream conditions that contribute to cancer. For example, overweight and obesity, a well-known risk factor for cancer, contributes to morbidity of cancer treatment, and has been linked to recurrence and secondary cancers [26-28]. CCC programs and coalitions can build on their past successes to increase access to healthy foods and promote physical activity by considering strategies that facilitate nutrition and exercise counseling services for cancer survivors and promote coverage of obesity screening, diagnosis, and treatment [28].

PSE efforts are increasingly recognized as a critical strategy for eliminating cancer disparities. For example, there continues to be racial and ethnic disparities regarding screening, treatment, and survival [29]. Rural residents often have higher cancer incidence and mortality than urban residents, and there are documented disparities related to cancer diagnosis and treatment [30]. Individuals with disabilities have unique challenges related to access and may navigate clinics that may not be accessible or may not be able to procure transportation to the clinic [31]. As a result, people with disabilities have lower cancer screening rates, are diagnosed at later stages, and have lower survival than people without disabilities [31]. Sexual and gender minority groups experience inequities in cancer risk factors and access to quality care, leading to disparate incidence, morbidity, and mortality in several cancers, yet these issues remain understudied and under addressed in cancer control programs [32-37]. CCC PSE efforts can be readily deployed in these arenas, bolstered by the growing evidence base on disparities.

Lastly, the evaluation and documentation of PSE efforts, both successful and unsuccessful, at the national, state, and local level is important to developing appropriate TAT activities and resources that have traction beyond cancer control. Evaluation findings are being shared more broadly, informing policy evaluation practice. Over the past 20 years, CCC programs and coalitions have helped to ensure that long lasting changes to the physical, social, and economic environments reduce the cancer burden in the United States. Using evidence-based PSE strategies makes reducing morbidity and mortality caused by cancer a realistic aspiration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the multitude of program staff, organizations, and volunteers across the states, tribes, and territories that have made policy, systems, and environmental changes for sustainable cancer control. We are appreciative of all the cancer control leaders who took the time to share their success stories publicly on Action4PSEchange.org and other platforms so others might learn and replicate elsewhere.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Given LS, Black B, Lowry G, Huang P, Kerner JF (2005) Collaborating to conquer cancer: a comprehensive approach to cancer control. Cancer Causes Control 16(Suppl 1):3–14. 10.1007/s10552-005-0499-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) About the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/about.htm. Accessed 21 Sept 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart S HN, Moore A, Bailey R, Brown P, Wanliss E (2019) Combating cancer through public health practice in the United States: an in-depth look at the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. In: Majumder AA (ed) Public Health. Intech Open, London [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selig WK, Jenkins KL, Reynolds SL, Benson D, Daven M (2005) Examining advocacy and comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control 16(1):61–68. 10.1007/s10552-005-0485-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steger C, Daniel K, Gurian GL, Petherick JT, Stockmyer C, David AM, Miller SE (2010) Public policy action and CCC implementation: benefits and hurdles. Cancer Causes Control 21(12):2041–2048. 10.1007/s10552-010-9668-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA (2014) Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet 384(9937):45–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frieden TR (2010) A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health 100(4):590–595. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Studlar D (2014) Cancer prevention through stealth: science, policy advocacy, and multilevel governance in the establishment of a "National Tobacco Control Regime" in the United States. J Health Polit Policy Law 39(3):503–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohan EA, Chovnick G, Rose J, Townsend JS, Young M, Moore AR (2018) Prioritizing population approaches in cancer prevention and control: results of a case study evaluation of policy, systems, and environmental change. Popul Health Manag 22(3):205–212. 10.1089/pop.2018.0081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend JS, Sitaker M, Rose J, Rohan E, Gardner A, Moore A (2019) Capacity building for the implementation of policy, systems, and environmental change: results from a survey of the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. Popul Health Manag 22(4):330–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner A, Geierstanger S, Miller Nascimento L, Brindis C (2011) Expanding organizational advocacy capacity: reflections from the field. Foundation Rev 3(1):4 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin JJ, Abesamis-Mendoza N (2012) Project CHARGE: building an urban health policy advocacy community. Prog Commun Health Partnersh 6(1):17–23. 10.1353/cpr.2012.0004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comprehensive Cancer Control National Partnership (2016) About us: the mission of the Comprehensive Cancer Control National Partnership. https://www.cccnationalpartners.org/about-us. Accessed 29 June 2018

- 14.Hefelfinger J, Patty A, Ussery A, Young W (2013) Technical assistance from state health departments for communities engaged in policy, systems, and environmental change: the ACHIEVE Program. Prev Chronic Dis 10:E175. 10.5888/pcd10.130093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leeman J, Calancie L, Hartman MA, Escoffery CT, Herrmann AK, Tague LE, Moore AA, Wilson KM, Schreiner M, Samuel-Hodge C (2015) What strategies are used to build practitioners’ capacity to implement community-based interventions and are they effective?: a systematic review. Implementation Science 10(1):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) CDC-RFA-DP13–1315: National support to enhance implementation of Comprehensive Cancer Control activities.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) CDC-RFA-DP17–1701: Cancer prevention and control programs for state, territorial, and tribal organizations.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010) CDC-RFA-DP10–1017 Demonstrating the capacity of Comprehensive Cancer Control Programs to implement policy and environmental cancer control interventions.

- 19.Brownson RC, Dodson EA, Stamatakis KA, Casey CM, Elliott MB, Luke DA, Wintrode CG, Kreuter MW (2011) Communicating evidence-based information on cancer prevention to state-level policy makers. J Natl Cancer Inst 10(4):306–316. 10.1093/jnci/djq529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter DJ (2009) Relationship between evidence and policy: a case of evidence-based policy or policy-based evidence? Public Health 123(9):583–586. 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macintyre S (2012) Evidence in the development of health policy. Public Health 126(3):217–219. 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sulik GA, Cameron C, Chamberlain RM (2012) The future of the cancer prevention workforce: why health literacy, advocacy, and stakeholder collaborations matter. J Cancer Educ 27(2 Suppl):S165–172. 10.1007/s13187-012-0337-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kegler MC, Honeycutt S, Davis M, Dauria E, Berg C, Dove C, Gamble A, Hawkins J (2015) Policy, systems, and environmental change in the Mississippi Delta: considerations for evaluation design. Health Educ Behav 42(1 Suppl):57S–66S. 10.1177/1090198114568428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fink A (2014) Evaluation fundamentals: insights into program effectiveness, quality, and value. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner AL, Brindis CD (2017) Advocacy and policy change evaluation: theory and practice. Stanford University Press, Stanford [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steele CB, Thomas C, Henley SJ, Massetti G, Galuska D, Agurs Collins T, Puckett M, Richardson L (2017) Vital Signs: trends in incidence of cancers associated with overweight and obesity—United States, 2005–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66(39):1052–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massetti GM, Dietz WH, Richardson LC (2018) Strategies to prevent obesity-related cancer-reply. JAMA 319(23):2442–2443. 10.1001/jama.2018.4952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puckett M, Neri A, Underwood JM, Stewart SL (2016) Nutrition and Physical activity strategies for cancer prevention in current national comprehensive cancer control program plans. J Commun Health 41(5):1013–1020. 10.1007/s10900-016-0184-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preston M, Mays G, Jones RD, Smith S, Stewart C, Henry Tillman R (2014) Reducing cancer disparities through community engagement in policy development: the role of cancer councils. J Health Care Poor Underserved 25(1 Suppl):139–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zahnd WE, James AS, Jenkins WD, Izadi SR, Fogleman AJ, Steward DE, Colditz GA, Brard L (2017) Rural-urban differences in cancer incidence and trends in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steele CB, Townsend JS, Courtney-Long EA, Young M (2017) Prevalence of cancer screening among adults with disabilities, United States, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 14:E09. 10.5888/pcd14.160312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, Vadaparampil ST, Nguyen GT, Green BL, Kanetsky PA, Schabath MB (2015) Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin 65(5):384–400. 10.3322/caac.21288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzales G, Zinone R (2018) Cancer diagnoses among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: results from the 2013–2016 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Causes Control 29(9):845–854. 10.1007/s10552-018-1060-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lisy K, Peters MDJ, Schofield P, Jefford M (2018) Experiences and unmet needs of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people with cancer care: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Psychooncology 27(6):1480–1489. 10.1002/pon.4674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudson J, Schabath MB, Sanchez J, Sutton S, Simmons VN, Vadaparampil ST, Kanetsky PA, Quinn GP (2017) Sexual and gender minority issues across NCCN guidelines: results from a national survey. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 15(11):1379–1382. 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wheldon CW, Schabath MB, Hudson J, Bowman Curci M, Kanetsky PA, Vadaparampil ST, Simmons VN, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, Quinn GP (2018) Culturally competent care for sexual and gender minority patients at National Cancer Institute-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers. LGBT Health 5(3):203–211. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cathcart-Rake EJ (2018) Cancer in sexual and gender minority patients: are we addressing their needs? Curr Oncol Rep 20(11):85. 10.1007/s11912-018-0737-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]