Key Points

Question

What is the incidence of dual allergy to cefazolin and natural penicillins?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 6147 patients from 77 studies. Forty-four patients were identified as allergic to a natural penicillin and cefazolin, resulting in a meta-analytical frequency of 0.7%.

Meaning

The low frequency of penicillin-cefazolin dual allergy suggests that most patients should receive cefazolin regardless of penicillin allergy history.

Abstract

Importance

Cefazolin is the preoperative antibiotic of choice because it is safer and more efficacious than second-line alternatives. Surgical patients labeled as having penicillin allergy are less likely to prophylactically receive cefazolin and more likely to receive clindamycin or vancomycin, which results in higher rates of surgical site infections.

Objective

To examine the incidence of dual allergy to cefazolin and natural penicillins.

Data Sources

MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase were searched without language restrictions for relevant articles published from database inception until July 31, 2020.

Study Selection

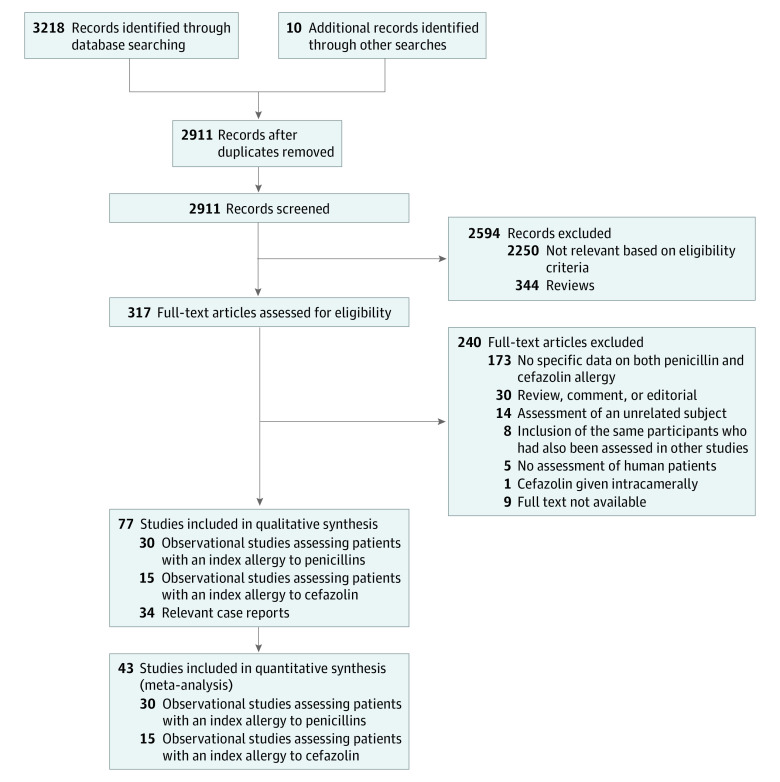

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, a search of MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase was performed for articles published from database inception to July 31, 2020, for studies that included patients who had index allergies to a natural penicillin and were tested for tolerability to cefazolin or that included patients who had index allergies to cefazolin and were tested for tolerability to a natural penicillin. A total of 3228 studies were identified and 2911 were screened for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were independently extracted by 2 authors. Bayesian meta-analysis was used to estimate the frequency of allergic reactions.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Dual allergy to cefazolin and a natural penicillin.

Results

Seventy-seven unique studies met the eligibility criteria, yielding 6147 patients. Cefazolin allergy was identified in 44 participants with a history of penicillin allergy, resulting in a dual allergy meta-analytical frequency of 0.7% (95% credible interval [CrI], 0.1%-1.7%; I2 = 74.9%). Such frequency was lower for participants with unconfirmed (0.6%; 95% CrI, 0.1%-1.3%; I2 = 54.3%) than for those with confirmed penicillin allergy (3.0%; 95% CrI, 0.01%-17.0%; I2 = 88.2%). Thirteen studies exclusively assessed surgical patients (n = 3884), among whom 0.7% (95% CrI, 0%-3.3%; I2 = 85.5%) had confirmed allergy to cefazolin. Low heterogeneity was observed for studies of patients with unconfirmed penicillin allergy who had been exposed to perioperative cefazolin (0.1%; 95% CrI, 0.1%-0.3%; I2 = 13.1%). Penicillin allergy was confirmed in 16 participants with a history of cefazolin allergy, resulting in a meta-analytical frequency of 3.7% (95% CrI, 0.03%-13.3%; I2 = 64.4%). The frequency of penicillin allergy was 4.4% (95% CrI, 0%-23.0%; I2 = 75%) for the 8 studies that exclusively assessed surgical patients allergic to cefazolin.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that most patients with a penicillin allergy history may safely receive cefazolin. The exception is patients with confirmed penicillin allergy in whom additional care is warranted.

This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the incidence of dual allergy to cefazolin and natural penicillins.

Introduction

More than 17 million surgical procedures are performed each year in the US.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention health care–associated infection prevalence survey estimated that there were 110 800 surgical site infections associated with inpatient operations.2 Cefazolin, a first-generation cephalosporin, is the guideline-recommended antibiotic for most surgical procedures.3,4 Cefazolin is the first-line treatment because it is the most widely studied, has the appropriate spectrum of activity against organisms commonly encountered in surgical site infections, is well tolerated, and has a low acquisition cost. However, the 10% of patients reporting a penicillin allergy are less likely to receive cefazolin and more likely to receive clindamycin or vancomycin, resulting in increased odds of developing a surgical site infection.5,6

Avoidance of cefazolin in patients with penicillin allergy is grounded in evidence from more than 40 years ago and is being increasingly called into question. Research from the 1960s and 1970s reported a cross-reactivity rate of 8% between penicillins and cephalosporins.7,8 The production process of penicillins included using a cephalosporin mold and has been blamed for the high rates of cross-reactivity observed before synthetic manufacturing of β-lactams became standard in the middle 1980s.9 Regardless of manufacturing improvements, the current US Food and Drug Administration label for all cephalosporins warns of a 10% cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins.9,10 Contemporary data have established that cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins is primarily based on the R1 side chain, not the shared β-lactam ring structure.11,12 Cefazolin does not share an R1 side chain with other penicillins or cephalosporins.9,13,14 This difference in R1 side chains should make cefazolin safe to administer in patients with a penicillin allergy. However, few studies have been published evaluating the incidence of allergy, or hypersensitivity, to natural penicillins (ie, penicillin, amoxicillin, and ampicillin) and cefazolin.

The primary outcome of this systematic review and meta-analysis is the incidence of dual allergy to cefazolin and natural penicillins. In addition, we aimed to identify variables associated with between-study differences in dual allergy between penicillins and cefazolin. The term cross-reactivity was not used as the primary outcome because it implies a biological reaction based on a common chemical structure that is unlikely between cefazolin and penicillins.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We included observational studies in which the primary outcome of dual allergy to a natural penicillin (penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin) and cefazolin could be assessed. Included studies consisted of (1) those assessing patients with self-reported or confirmed allergy to a natural penicillin who were exposed to cefazolin or tested for cefazolin allergy and (2) those assessing patients with self-reported or confirmed cefazolin allergy who were exposed to, or tested for, penicillin allergy. We did not apply exclusion criteria based on publication date, status, or language. This systematic review with meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guideline.

Information Sources and Search Methods

Two of us (B.S.-P. and M.N.J.) searched 3 electronic bibliographic databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase) for articles published from database inception to July 31, 2020. Search queries are listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Searches on electronic bibliographic databases were complemented by reviewing the references of included primary studies and by contacting authors.

Study Selection and Data Collection

After duplicates were removed, each study was independently assessed by 2 reviewers (all authors in pairs), first by title and abstract screening and second by full-text reading. Non–English-language articles were translated before full-text reading. Data from included primary studies were independently extracted by 2 reviewers (all authors in pairs) using purposely built online forms. For each study, we retrieved information on variables that potentially explained differences in the results, including publication year, country, sampling method (consecutive or convenience), clinical setting, participants’ age group, and characteristics of the index reactions. Index reaction details included culprit drugs, diagnostic tests, clinical manifestations, and timing of allergic reaction. Immediate reactions were defined as those occurring during the first hour after exposure to the culprit drug, with the remaining reactions classified as nonimmediate.

For studies in which the index allergic reaction was a penicillin, we retrieved data on the number of patients with self-reported or confirmed penicillin allergy as well as the number of those who also had a cefazolin allergy, gathering information about whether the latter was confirmed by skin testing, in vitro testing (ie, specific IgE test), drug challenges (ie, a controlled or stepwise drug exposure), and/or drug exposure for prophylactic or therapeutic purposes. Likewise, for studies in which the index allergic reaction was cefazolin, we retrieved information on the number of patients with cefazolin allergy and those who also had a penicillin allergy (as well as on how the latter was confirmed).

Disagreements between reviewers in data selection or extraction were solved by consensus. Authors of primary studies were contacted to provide missing information, including from unpublished studies.

Quality Assessment

The quality of included primary studies was independently assessed by 2 researchers (B.S.-P., K.G.B., and/or M.N.J.) using an adaptation from the checklist developed by Hoy et al15 for prevalence studies. Of the 11 items, we used 5 that were deemed adequate for this study, namely (1) if the sample was representative of the target population; (2) if random or consecutive sampling methods were used; (3) if the likelihood of nonresponse bias was minimal (ie, if >75% participants with index allergy to penicillins underwent testing and/or exposure to cefazolin or vice versa); (4) if an acceptable or sufficiently complete definition of allergic or hypersensitivity reaction was used in the study; and (5) if the same methods of assessment and data collection were used for all study participants.

Quantitative Synthesis of Results

We performed bayesian meta-analysis following a random-effects model based on a binomial likelihood to estimate the frequency of allergic reactions to cefazolin in patients with history of penicillin allergy and the frequency of allergic reactions to penicillins in patients with history of cefazolin allergy.16 We opted for this approach because it can more adequately handle proportions equal to 0, which were frequent in included primary studies. By contrast, a frequentist approach would require adding a continuity correction (eg, 0.5) to the proportions equal to 0, which might bias meta-analytical results.

Bayesian methods yield probability distributions of the parameters of interest (posterior probabilities) based on prior probability distributions and on the observed data. In this study, we used meta-analytical methods to estimate the posterior probabilities of the frequency of developing allergic reactions. Of those posterior probabilities, we retrieved the median value and the respective 95% credible intervals (CrIs) (range of values within which, with 95% probability, the true frequency of allergic reactions lies). For building bayesian models, we used uninformative prior distributions for the effect size measure and for the tau parameter (dnorm [0,0.00001] and dgamma [0.00001,0.00001], respectively).

We assessed heterogeneity (existence of differences beyond those that would be expected by random sampling only) by computing estimates of the I2 statistic, with I2 greater than 50% indicative of severe heterogeneity. Heterogeneity sources were explored by means of meta-regression methods and subgroup analysis. Exponentials of meta-regression coefficients were interpreted as odds ratios (ORs).

Meta-analysis was performed using the rjags package of R software, version 4.0.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). For each analysis, we ran at least 30 000 iterations with a burn-in of 15 000 sample iterations.

Results

The search yielded 3218 records, of which 307 were duplicates (Figure 1). After the screening phase, 317 articles remained. A total of 77 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. Of note, the full texts of 9 articles were not available even after contacting the authors. Eight articles were not included despite meeting the eligibility criteria of this systematic review because the participants had also been assessed in included publications with larger samples.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flow Diagram for Study Selection.

Two studies assessed both patients with index allergy to penicillins tested for cefazolin and patients with index allergy to cefazolin tested for penicillins.

Of the 77 included primary studies, 43 were cohort studies (eTable 2 in the Supplement), which were quantitatively assessed by meta-analysis. The remainder were case reports, whose description is available in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Frequency of Cefazolin Allergy in Patients With Penicillin Allergy

We included 30 primary studies17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 that assessed the frequency of cefazolin allergy in series of patients with self-reported or confirmed penicillin allergy (Table 1). The included primary studies17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 had been published between 1976 and 2020, assessing a total of 6001 participants. In 9 studies,18,20,25,34,36,38,39,40,44 penicillin allergy was confirmed by diagnostic testing (skin, in vitro, and/or drug challenges). In 13 studies,18,20,22,23,25,31,32,34,37,38,39,40,44 cefazolin allergy was assessed by means of skin tests or drug challenges, whereas prophylactic or therapeutic introduction of cefazolin occurred in 18 studies.17,19,21,24,26,27,28,29,30,33,35,36,37,41,42,43,45,46

Table 1. Meta-regression and Subgroup Analyses for the Frequency of Cefazolin Allergy in Patients With Index Self-reported or Confirmed Allergy to Penicillins.

| Variablea | No. of studies | No. of patients | Subgroup analyses | Univariable meta-regression, OR (95% CrI) | Probability of OR <1, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe reaction, % (95% CrI) | I2, % | |||||

| All primary studies | ||||||

| All | 30 | 6001 | 0.7 (0.1-1.7) | 74.9 | NA | NA |

| Year of publication | 30 | 6001 | NA | NA | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 49 |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| North America | 21 | 5547 | 0.8 (0.1-2.2) | 75.2 | 5.03 (0.11-28.00)b | 37 |

| Europe | 7 | 431 | 0.6 (0-1.0) | 7.9 | NA | |

| Setting | ||||||

| Surgical patients | 13 | 3884 | 0.7 (0-3.3) | 85.5 | 2.39 (0.09-12.01)b | 48 |

| Pregnant women | 3 | 1405 | 0.7 (0-2.3) | 29.2 | NA | NA |

| Referenced patients to an outpatient clinic | 7 | 490 | 1.0 (0-4.8) | 81.1 | NA | NA |

| Inpatients and ED patients | 7 | 222 | 2.7 (0.7-6.1) | 16.8 | NA | NA |

| Sampling method | ||||||

| Convenience | 20 | 5450 | 0.5 (0.1-1.4) | 74.6 | 2.27 (0.03-9.01)b | 67 |

| Consecutive | 6 | 520 | 2.5 (0-14.7) | 77.3 | NA | |

| Index allergy to penicillins | ||||||

| Unconfirmed by diagnostic tests | 21 | 5487 | 0.6 (0.1-1.3) | 54.3 | 0.36 (0.02-1.83)b | 92 |

| Confirmed by diagnostic tests | 9 | 514 | 3.0 (0-17.0) | 88.2 | NA | NA |

| Exclusion of studies assessing nonimmediate index reactionsc | 26 | 5843 | 0.7 (0.2-1.8) | 72.5 | NA | NA |

| Assessment of cefazolin allergy | ||||||

| Skin tests | 8 | 455 | 3.7 (0-28.9) | 91.4 | 8.75 (0.41-42.67) | 9 |

| Prophylactic or therapeutic exposure | 18 | 5266 | 0.4 (0.1-0.8) | 41.0 | 0.19 (0.01-0.82) | 98 |

| Studies’ methodologic quality | 30 | 6001 | NA | NA | 0.91 (0.30-2.37)d | 69 |

| Classification for most items | ||||||

| Low risk of bias | 16 | 3607 | 0.7 (0.1-1.9) | 62.5 | 1.54 (0.08-8.99)b | 63 |

| High risk of bias | 14 | 2394 | 0.8 (0-3.3) | 83.5 | NA | NA |

| Studies exclusively assessing surgical patients | ||||||

| Year of publication | 13 | 3884 | NA | NA | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | 99 |

| Geographic region | 13 | 3884 | NRe | NRe | NRe | NA |

| Sampling method | ||||||

| Convenience | 10 | 3738 | 0.4 (0-2.1) | 86.8 | 1.30 (<0.01-6.00)b | 93 |

| Consecutive | 2 | 141 | NRf | NRf | NRf | NA |

| Index allergy to penicillins | ||||||

| Unconfirmed by diagnostic tests | 11 | 3860 | 0.3 (0-1.0) | 66.5 | 0.01 (<0.01-0.06)b | 99 |

| Confirmed by diagnostic tests | 2 | 24 | NRf | NRf | NRf | NA |

| Exclusion of studies assessing nonimmediate index reactions | 11 | 3749 | 1.3 (0-6.1) | 85.3 | NA | NA |

| Assessment of cefazolin allergy | ||||||

| Skin tests | 2 | 24 | NRf | NRf | NRf | NA |

| Prophylactic or therapeutic exposure | 10 | 3721 | 0.1 (0.1-0.3) | 13.1 | 0.01 (<0.01-0.06)b | >99 |

|

||||||

| Classification of most items | ||||||

| Low risk of bias | 7 | 2966 | 0.8 (0-9.4) | 77.3 | NRf | NA |

| High risk of bias | 6 | 918 | 2.0 (0-12.5) | 95.7 | NRf | NA |

Abbreviations: CrI, credible interval; ED, emergency department; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio.

For some variables, the number of studies and patients in the categories do not sum to 30 and 6001, respectively, because there were studies belonging to other categories (with insufficient numbers of patients to be used in subgroup analyses or meta-regression) or with missing information.

Compared with all other categories of the respective variable.

Subgroup analysis restricted to data from participants with index reactions of immediate type (available from 4 studies) of 0.6% (95% CrI, 0.1%-1.1%). Subgroup analysis restricted to data from participants with index reactions of nonimmediate type (available from 6 studies) of less than 0.1% (95% CrI, 0%-1.2%).

Meta-regression on the number of items classified as low risk of bias.

All studies that exclusively assessed surgical patients were performed in North America.

Analysis not possible on account of the insufficient number of primary studies or participants.

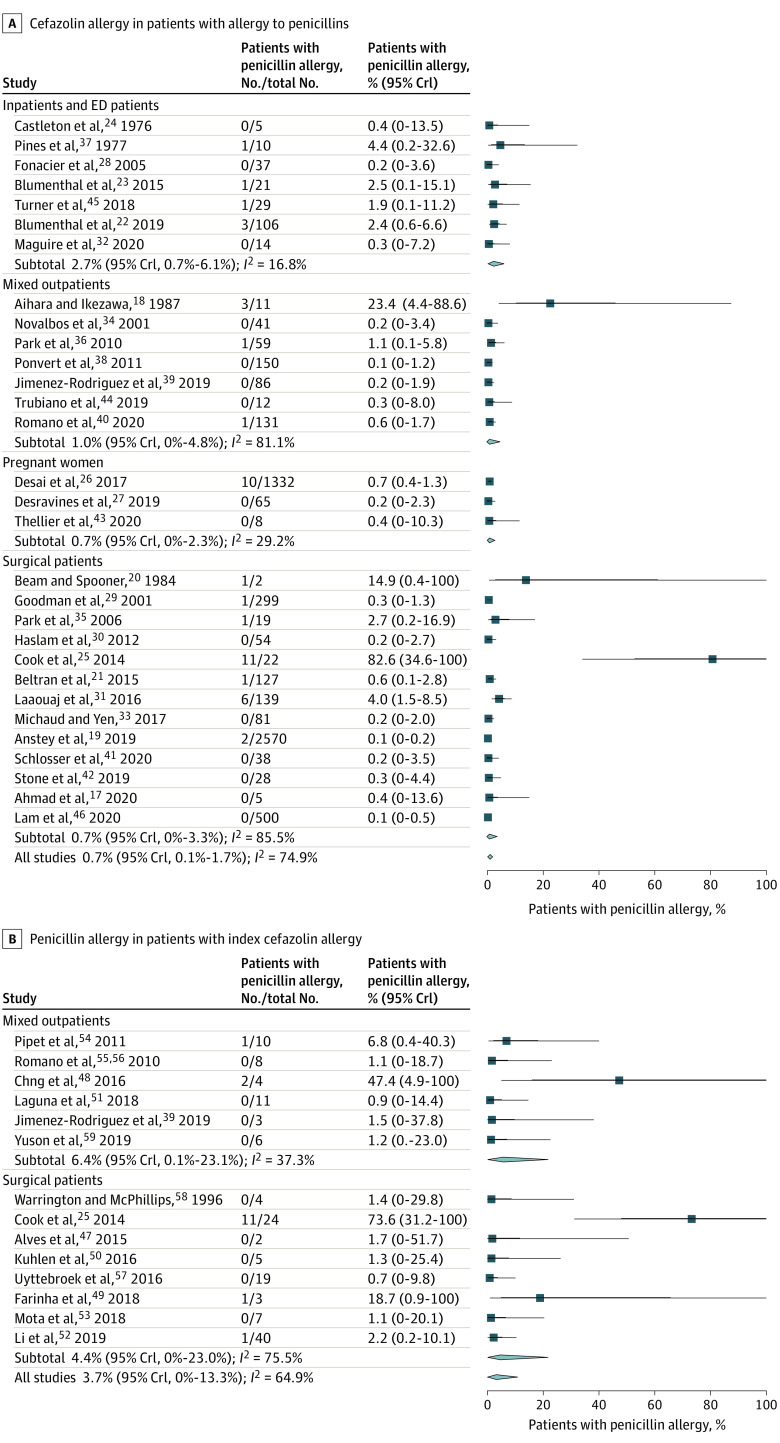

Cefazolin allergy was identified in 44 participants, resulting in a meta-analytical frequency of 0.7% (95% CrI, 0.1%-1.7%; I2 = 74.9%) (Figure 2A). Such frequency was lower for participants with self-reported penicillin allergy (0.6%; 95% CrI, 0.1%-1.3%; I2 = 54.3%) than for those with confirmed allergic reactions (3.0%; 95% CrI, 0.01%-17.0%; I2 = 88.2%) (OR, 0.4; 95% CrI, 0.02-1.8; 92% probability of OR <1).

Figure 2. Forest Plots on the Frequency of Dual Allergy to Penicillins and Cefazolin.

CrI indicates credible interval; ED, emergency department. The width of the diamonds corresponds to the length of the 95% CrI for the meta-analytical pooled result. Thin lines indicate the length of the 95% CrI for each primary study. Thick lines indicate the length of the 68% CrI for each primary study.

Thirteen studies17,19,20,21,25,29,30,31,33,35,41,42,46 exclusively assessed surgical patients (n = 3884), among whom 0.7% had confirmed allergy to cefazolin (95% CrI, 0%-3.3%; I2 = 85.5%). Unconfirmed penicillin allergy was associated with lower risk of cefazolin allergy (OR, 0.01; 95% CrI, <0.01-0.1). Ten studies17,19,21,29,30,33,35,41,42,46 described patients with unconfirmed penicillin allergy who had been exposed to perioperative cefazolin, resulting in a dual allergy frequency of 0.1% (95% CrI, 0.1%-0.3%; I2 = 13.1%).

Frequency of Penicillin Allergy in Patients With Cefazolin Allergy

We included 15 primary studies25,39,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 that assessed the frequency of penicillin allergy in series of patients with cefazolin allergy (Table 2). The included primary studies25,39,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 assessed a total of 146 participants. All patients had confirmed cefazolin allergy. Seven studies47,49,50,52,53,57,58 included only patients who had had anaphylactic reactions to cefazolin. Penicillin allergy was assessed by means of drug challenge or exposure in 9 studies.47,49,50,51,52,53,54,57,59 Thirteen studies25,39,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 assessed penicillin allergy status by skin tests.

Table 2. Meta-regression and Subgroup Analyses for the Frequency of Penicillin Allergy in Patients With Index Cefazolin Allergy.

| Variablea | No. of studies | No. of patients | Subgroup analyses | Univariable meta-regression, OR (95% CrI) | Probability of OR <1, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe reaction, % (95% CrI) | I2, % | |||||

| All | 15 | 146 | 3.7 (0-13.3) | 64.9 | NA | NA |

| Year of publication | 15 | 146 | NA | NA | 0.98 (0.95-1.01) | 85 |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| Europe | 9 | 63 | 3.7 (0-11.0) | 11.1 | 3.53 (<0.01-8.11)b | 86 |

| North America | 3 | 33 | NRc | NRc | NA | NA |

| Setting | ||||||

| Surgical patients | 8 | 104 | 4.4 (0-23.0) | 75.5 | NRc | NA |

| Referenced patients to an outpatient clinic | 7 | 42 | 6.4 (0.1-23.1) | 37.3 | NA | NA |

| Sampling method | ||||||

| Convenience | 8 | 64 | 10.0 (0-54.1) | 70.6 | NRc | NA |

| Consecutive | 5 | 77 | 1.1 (0-4.7) | 22.4 | NA | NA |

| Timing of index reactions | ||||||

| Immediate | 12 | 115 | 2.8 (0.8-4.9) | 3.4 | 0.04 (0.01-0.11)b | 99 |

| Immediate and nonimmediate | 3 | 31 | NRc | NRc | NA | NA |

| Clinical manifestations of index reactions | ||||||

| Anaphylaxis onlyd | 7 | 80 | 2.7 (0.8-3.9) | 0.9 | 3.46 (<0.01-10.50)b | 87 |

| Different reactions | 8 | 66 | 10.6 (0-48.8) | 66.4 | NA | NA |

| Assessment of penicillin allergy | ||||||

| Skin tests | 13 | 104 | 3.7 (0-16.6) | 72.1 | NRc | NA |

| Drug challenge or exposure | 9 | 103 | 2.5 (0.7-5.6) | 3.5 | 0.67 (0.01-1.46)b | 96 |

| Studies’ methodologic quality | ||||||

| Classification of most items | ||||||

| Low risk of bias | 11 | 109 | 4.6 (0.3-9.4) | 11.9 | 0.49 (0.09-1.40)e | 95 |

| High risk of bias | 4 | 37 | 15.2 (0-100) | 93.4 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: CrI, credible interval; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio.

For some variables, the number of studies and patients in the categories do not sum to 15 and 146, respectively, because there were studies belonging to other categories (with insufficient numbers of patients to be used in subgroup analyses or meta-regression) or with missing information.

Compared with all other categories of the respective variable.

Analysis not possible on account of the insufficient number of primary studies or participants.

All primary studies concerned surgical patients.

Meta-regression on the number of items classified as low risk of bias.

Penicillin allergy was confirmed in 16 participants, corresponding to a meta-analytical frequency of 3.7% (95% CrI, 0.03%-13.3%; I2 = 64.9%) (Figure 2B). Lower heterogeneity was observed when assessing studies that only assessed immediate reactions (subgroup frequency, 2.8%; 95% CrI, 0.8%-4.9%; I2 = 3.4%).

Eight studies25,47,49,50,52,53,57,58 exclusively assessed surgical patients (n = 104), among whom 4.4% had confirmed allergy to penicillins (95% CrI, 0%-23.0%; I2 = 75.5%). In all surgical studies25,47,49,50,52,53,57,58 that exclusively assessed immediate reactions to cefazolin, all participants had anaphylaxis as their index reaction. Among these patients, 2.7% (95% CrI, 0.8%-3.9%; I2 = 0.9%) had confirmed allergy to penicillin.

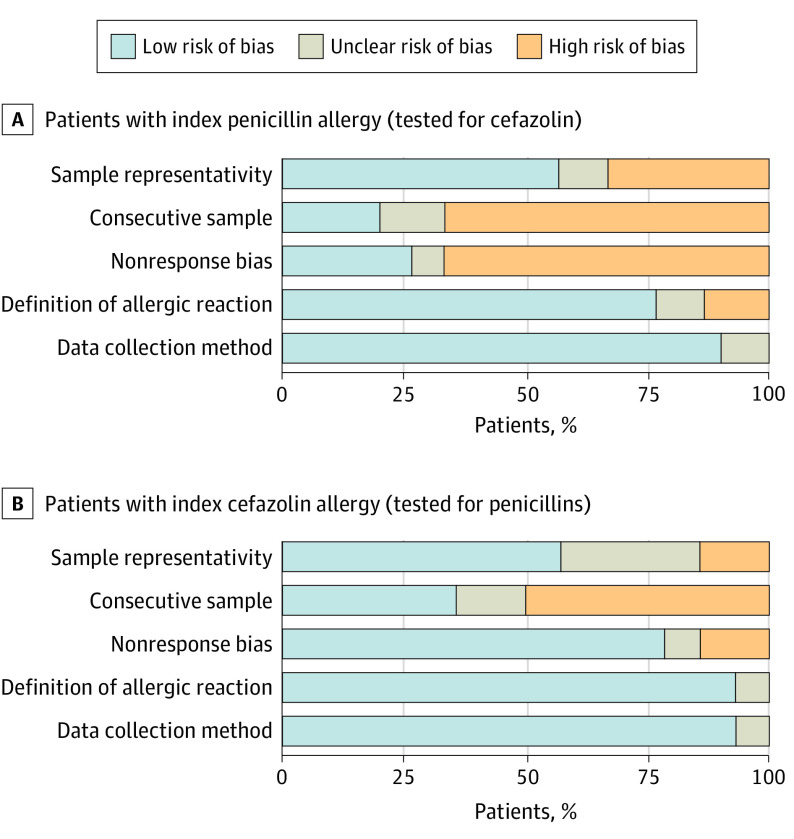

Quality Assessment

A risk of bias graph is presented in Figure 3, whereas the risk of bias summary for each included primary study is presented in eTable 4 in the Supplement. Overall, the items with the largest number of studies classified as having a high risk of bias concerned the sampling methods and the possibility of nonassessment bias. Eight studies38,40,44,50,52,53,57,59 had all items classified as low risk of bias.

Figure 3. Risk of Bias for Included Primary Studies.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the frequency of patient allergies to a natural penicillin and cefazolin. The study assessed 6001 patients with an allergy to a natural penicillin who subsequently received or were tested for an allergy to cefazolin. Forty-four of these patients were identified as allergic to cefazolin, resulting in a meta-analytical frequency of 0.7%. The frequency of dual allergy was higher among patients with confirmed penicillin allergies (3.0%) compared with patients with self-reported or unconfirmed penicillin allergies (0.6%). The meta-analytical frequency of dual allergy for surgical patients was 0.7%, with surgical patients with unconfirmed penicillin allergies having an even lower rate of dual allergy (0.1%). A total of 146 patients had an index allergy to cefazolin and subsequently received or were tested for an allergy to a natural penicillin; in this cohort, the frequency of dual allergy was 3.7% and 4.4% considering surgical patients only. These results are consistent with those from Picard et al,60 who identified a dual allergy frequency for penicillin-cefazolin of 1.3% based on 3 primary studies that involved a total of 75 patients.

Debate about cross-reactivity vs dual allergy among β-lactam antibiotics remains a contemporary issue.61 It is possible that some patients experience a cross-reactivity to the β-lactam ring structure based on the higher frequency of dual penicillin and cefazolin hypersensitivity from studies12,18,25,62 that used skin testing as their diagnostic method. However, it may be that this higher risk is only observed in patients with IgE-mediated allergies or that it may mirror false-positive results because the positive predictive value of skin tests appears limited.63 An alternative explanation of a higher dual allergy rate for patients with a confirmed penicillin allergy is multiple drug hypersensitivity syndrome. The prevalence of multiple drug hypersensitivity syndrome was 1.2%, according to a study by Blumenthal et al64 that assessed nearly 800 000 patients.

One of the most intriguing studies to assess the controversy of cross-reactivity and multiple drug allergy syndrome is from Strom et al,65 who analyzed the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database. This large case-control study found that patients with no history of drug allergy had a lower frequency of allergic reactions to sulfonamide nonantibiotics (1.1%) compared with patients with history of allergic reactions to sulfonamide antibiotics (9.9%) and patients with a history of penicillin allergy (14.2%). Because penicillins and sulfa drugs are not chemically similar, the authors concluded that the high rate of allergic reactions between sulfa antibiotics and sulfa nonantibiotics was attributable to a greater predisposition to allergic reactions in general among patients with a history of medication allergies.66,67 Although the current meta-analysis did not assess the frequency of allergic reactions to a non–β-lactam, we were able to identify 19 primary studies (among the 240 articles that were fully read in the selection stage of this systematic review) that reported on the frequency of cefazolin allergic reactions in patients with no registration of penicillin allergy. On the basis of data from 13 149 patients, we obtained a meta-analytical frequency of 0.6% (95% CrI, 0.1%-1.2%; I2 = 59.0%), close to that observed for patients with penicillin allergy. In addition, our observed low rate of dual allergy should increase practitioner confidence in using cefazolin in patients allergic to penicillins, particularly when data suggest cefazolin is the optimal antibiotic, such as perioperative prophylaxis.

In the performed meta-analyses, severe heterogeneity was observed. A meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to identify potential variables that could explain differences across primary studies. Higher rates of dual allergy were seen with studies from the 1970s and 1980s18,20,37 and those with small samples.25,48,49,54 We also observed that having an unconfirmed penicillin allergy and being prophylactically or therapeutically exposed to cefazolin without previous testing was associated with lower risk of developing a cefazolin hypersensitivity reaction. This finding may be attributable to a selection bias in the real-world observational studies, with practitioners selecting lower-risk patients with penicillin allergy to prophylactically or therapeutically receive cefazolin. Notably, severe heterogeneity was not identified when performing a meta-analysis limited to surgical patients who self-reported penicillin allergy and received cefazolin without previous testing. Unfortunately, there was no information available in the primary studies on several variables that may also contribute to explain heterogeneity, such as the proportion of patients with allergy to other medications or the presence of other immunologic comorbidities.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has strengths. To our knowledge, this is the most extensive systematic review and meta-analysis conducted to assess the frequency of cross-reactivity between natural penicillins and cefazolin and the first fully dedicated to this research question with the aim of improving perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. One prior study60 assessed the cross-reactivity rate for penicillin-cefazolin in 3 primary studies that involved a total of 75 patients, finding a 1.3% reaction rate. Our bayesian methods allowed us to appropriately summarize data that included 0 cells. We also performed meta-regression and subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity, identifying variables that explained differences across studies. To minimize publication and information bias, we searched 3 different electronic bibliographic databases without applying exclusion criteria based on the date or language of publication and contacted authors whenever relevant information was missing. Relevance to clinical practice is the final strength of this study because the results could lead to the standardization of preoperative cefazolin in patients with unconfirmed penicillin allergies, thus decreasing surgical site infections.

The study also has limitations, mostly related to the methods of the included primary studies. The possibility of selection bias exists. It is likely that only a small percentage of patients with a natural penicillin allergy who get tested for and/or exposed to cefazolin are described in the literature. In addition, in many primary studies, not all patients reporting a penicillin allergy were prophylactically or therapeutically exposed to cefazolin, which may have biased our sample. Unfortunately, information was lacking on whether those patients who did not receive cefazolin tended to be different (eg, regarding the symptoms or severity of their index allergy) from those who were exposed to this drug. A possibility of information bias also exists. For example, surgery studies reporting only reactions in the surgery setting would miss delayed hypersensitivity reactions. The most significant limitation, however, is the lack of specific information about each allergic reaction because cross-reactivity is not plausible in patients who experience different physiologic reactions to each antibiotic (eg, anaphylaxis [IgE mediated] to cefazolin and contact dermatitis [T-cell mediated] to penicillin). Without individual-level data describing risk factors for medication allergies, including existing immunologic diseases and history of other medication allergies, we could not clarify cross-study differences or distinguish between probability of cross-reactivity and multiple drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Finally, the small number of patients with index cefazolin allergy limited meta-regression analyses.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that cross-reactivity between penicillins and cefazolin was rare, with hypersensitivity reactions to cefazolin occurring in less than 1% of patients with unconfirmed penicillin allergy and in 3% of patients with allergy confirmation. Similar results were observed when specifically analyzing the surgical setting, with only 1 hypersensitivity reaction in each 1000 patients with unconfirmed penicillin allergy receiving cefazolin. These results suggest that most patients with a penicillin allergy history undergoing surgical prophylaxis may safely receive cefazolin. The exception may be those patients with confirmed penicillin allergy or a history of severe reactions, in whom additional care is warranted. The increased incidence of dual allergy may not be specific to cefazolin and may extend to other perioperative antibiotics. Future primary studies and systematic reviews should assess the frequency of allergic reactions to other antibiotics in surgical patients with confirmed penicillin allergy. These reassuring findings are broadly relevant to surgery because there are clear patient care consequences of avoiding cefazolin for surgical prophylaxis.

eTable 1. Search Queries Used in the Different Electronic Bibliographic Databases

eTable 2. Characteristics of Included Cohort Studies

eTable 3. Characteristics of Case Reports Included

eTable 4. Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

References

- 1.McDermott KW, Freeman WJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Operating Room Procedures During Inpatient Stays in U.S. Hospitals. Statistical Brief 233. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magill SS, O’Leary E, Janelle SJ, et al. ; Emerging Infections Program Hospital Prevalence Survey Team . Changes in prevalence of health care-associated infections in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1732-1744. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. ; American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP); Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA); Surgical Infection Society (SIS); Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) . Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14(1):73-156. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.9999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, et al. American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(1):59-74. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen JL, Shenoy ES. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):329-336. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Huang M, et al. The impact of reporting a prior penicillin allergy on the treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petz LD, Fudenberg HH. Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia caused by penicillin administration. N Engl J Med. 1966;274(4):171-178. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196601272740401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dash CH. Penicillin allergy and the cephalosporins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1975;1(3)(suppl):107-118. doi: 10.1093/jac/1.suppl_3.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DePestel DD, Benninger MS, Danziger L, et al. Cephalosporin use in treatment of patients with penicillin allergies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(4):530-540. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cefazolin [package insert]. Braun Medical Inc, 2007.

- 11.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Maggioletti M, Caruso C, Quaratino D. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of aztreonam and cephalosporins in subjects with a T cell–mediated hypersensitivity to penicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):179-186. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romano A, Valluzzi RL, Caruso C, Maggioletti M, Quaratino D, Gaeta F. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of cephalosporins in patients with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to penicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1662-1672. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trubiano JA, Stone CA, Grayson ML, et al. The 3 Cs of antibiotic allergy-classification, cross-reactivity, and collaboration. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1532-1542. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zagursky RJ, Pichichero ME. Cross-reactivity in β-lactam allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):72-81.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934-939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welton N, Cooper AJ, Abrams NJ, Ades KR. Evidence Synthesis for Decision Making in Healthcare. Statistics in Practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad H, Trytko U, Bandi S. Decreasing peri-operative non-beta-lactam antibiotics with screening tool [conference abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(2):AB56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aihara M, Ikezawa Z. Evaluation of the skin test reactions in patients with delayed type rash induced by penicillins and cephalosporins. J Dermatol. 1987;14(5):440-448. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1987.tb03607.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anstey K, Anstey J, Hilts-Horeczko A, Doernberg SB, Chen LL, Otani IM. Perioperative use and safety of cephalosporin antibiotics in patients with documented penicillin allergy [conference abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(2):AB29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.12.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beam TR Jr, Spooner J. Cross allergenicity between penicillins and cephalosporins. Chemioterapia. 1984;3(6):390-393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beltran RJ, Kako H, Chovanec T, Ramesh A, Bissonnette B, Tobias JD. Penicillin allergy and surgical prophylaxis: cephalosporin cross-reactivity risk in a pediatric tertiary care center. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(5):856-859. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Hsu JT, et al. Outcomes from an inpatient beta-lactam allergy guideline across a large US health system. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(5):528-535. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):294-300.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castleton B, Goodwin CS, Stirling J, Pitcher-Wilmott R, Elton A. Cephazolin treatment of pneumonia in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1976;5(3):181-187. doi: 10.1093/ageing/5.3.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook DJ, Barbara DW, Singh KE, Dearani JA. Penicillin skin testing in cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147(6):1931-1935. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai SH, Kaplan MS, Chen Q, Macy EM. Morbidity in pregnant women associated with unverified penicillin allergies, antibiotic use, and group B streptococcus infections. Perm J. 2017;21:16-080. doi: 10.7812/TPP/16-080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desravines N, Venkatesh KK, Hopkins A, et al. Intrapartum group B Streptococcus antibiotic prophylaxis in penicillin allergic pregnant women. AJP Rep. 2019;9(3):e238-e243. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1694031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fonacier L, Hirschberg R, Gerson S. Adverse drug reactions to a cephalosporins in hospitalized patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26(2):135-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman EJ, Morgan MJ, Johnson PA, Nichols BA, Denk N, Gold BB. Cephalosporins can be given to penicillin-allergic patients who do not exhibit an anaphylactic response. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13(8):561-564. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8180(01)00329-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haslam S, Yen D, Dvirnik N, Engen D. Cefazolin use in patients who report a non-IgE mediated penicillin allergy: a retrospective look at adverse reactions in arthroplasty. Iowa Orthop J. 2012;32:100-103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laaouaj J, O’Hara G, Philippon F, et al. Management of penicillin allergy in cardiac device infection prophylaxis: The use of cefazolin test dose. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(10)(suppl 1):S138. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maguire M, Hayes BD, Fuh L, et al. Beta-lactam antibiotic test doses in the emergency department. World Allergy Organ J. 2020;13(1):100093. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaud L, Yen D. First Place Award: can cefazolin be used in orthopaedic surgery for patients with a self-reported non-IgE mediated penicillin allergy? a prospective case series. Curr Orthop Pract. 2017;28(4):338-340. doi: 10.1097/BCO.0000000000000528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novalbos A, Sastre J, Cuesta J, et al. Lack of allergic cross-reactivity to cephalosporins among patients allergic to penicillins. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31(3):438-443. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.00992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park M, Markus P, Matesic D, Li JT. Safety and effectiveness of a preoperative allergy clinic in decreasing vancomycin use in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):681-687. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61100-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park MA, Koch CA, Klemawesch P, Joshi A, Li JT. Increased adverse drug reactions to cephalosporins in penicillin allergy patients with positive penicillin skin test. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153(3):268-273. doi: 10.1159/000314367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pines A, Nandi AR, Raafat H, Rahman. Cephazolin in severe purulent exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Preliminary study. Chemotherapy. 1977;23(2):114-120. doi: 10.1159/000221979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponvert C, Perrin Y, Bados-Albiero A, et al. Allergy to betalactam antibiotics in children: results of a 20-year study based on clinical history, skin and challenge tests. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22(4):411-418. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jimenez-Rodriguez TW, Blanca-Lopez N, Ruano-Zaragoza M, et al. Allergological study of 565 elderly patients previously labeled as allergic to penicillins. J Asthma Allergy. 2019;12:421-435. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S232787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romano A, Valluzzi RL, Caruso C, Zaffiro A, Quaratino D, Gaeta F. Tolerability of cefazolin and ceftibuten in patients with IgE-mediated aminopenicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(6):1989-1993.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlosser KA, Maloney SR, Horton JM, et al. The association of penicillin allergy with outcomes after open ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(9):4148-4156. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07183-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stone AH, Kelmer G, MacDonald JH, Clance MR, King PJ. The impact of patient-reported penicillin allergy on risk for surgical site infection in total joint arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(22):854-860. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thellier C, Subtil D, Pelletier de Chambure D, et al. An educational intervention about the classification of penicillin allergies: effect on the appropriate choice of antibiotic therapy in pregnant women. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2020;41:22-28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trubiano JA, Chua KYL, Holmes NE, et al. Safety of cephalosporins in penicillin class severe delayed hypersensitivity reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(3):1142-1146.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner NA, Moehring R, Sarubbi C, et al. Influence of reported penicillin allergy on mortality in MSSA bacteremia. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(3):ofy042. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lam PW, Tarighi P, Elligsen M, et al. Impact of the allergy clarification for cefazolin evidence-based prescribing tool on receipt of preferred perioperative prophylaxis: an interrupted time series study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(11):2955-2957. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alves C, Romeira A, Pinto P. Hypersensitivity to cefazolin-case series [conference abstract]. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;70:332. doi: 10.1111/all.12719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chng HH, Chan YLG, Thong B, et al. Skin testing and drug provocation test in the evaluation of cephalosporin allergy [conference abstract]. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;71:94. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farinha SM, Cardoso BK, Tomaz EM, Inácio FF. Cefazolin allergy-different sensitization profiles [conference abstract]. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8(suppl 3):33. doi: 10.1186/s13601-018-0217-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuhlen JL, Camargo CA, Balekian DS, et al. Antibiotics are the most commonly identified cause of perioperative hypersensitivity reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):697-704. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laguna JJ, Jimenez Blanco A, González-Mendiola R, et al. Incidence of immediate hypersensitivity reactions to cefazolin in our hospital: eighteen years evaluation [conference abstract]. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;73:148. doi: 10.1111/all.13537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li J, Green SL, Krupowicz BA, et al. Cross-reactivity to penicillins in cephalosporin anaphylaxis. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(6):e532-e534. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mota I, Gaspar Â, Morais-Almeida M. Perioperative anaphylaxis including Kounis syndrome due to selective cefazolin allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;177(3):269-273. doi: 10.1159/000490182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pipet A, Veyrac G, Wessel F, et al. A statement on cefazolin immediate hypersensitivity: data from a large database, and focus on the cross-reactivities. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(11):1602-1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03846.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Caruso C, Rumi G, Bousquet PJ. IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to cephalosporins: cross-reactivity and tolerability of penicillins, monobactams, and carbapenems. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(5):994-999. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, et al. IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to cephalosporins: cross-reactivity and tolerability of alternative cephalosporins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(3):685-691.E3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uyttebroek AP, Decuyper II, Bridts CH, et al. Cefazolin hypersensitivity: toward optimized diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(6):1232-1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Warrington RJ, McPhillips S. Independent anaphylaxis to cefazolin without allergy to other beta-lactam antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98(2):460-462. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(96)70171-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yuson C, Kumar K, Le A, et al. Immediate cephalosporin allergy. Intern Med J. 2019;49(8):985-993. doi: 10.1111/imj.14229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Picard M, Robitaille G, Karam F, et al. Cross-reactivity to cephalosporins and carbapenems in penicillin-allergic patients: two systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(8):2722-2738.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Macy E, Blumenthal KG. Are cephalosporins safe for use in penicillin allergy without prior allergy evaluation? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):82-89. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Empedrad R, Darter AL, Earl HS, Gruchalla RS. Nonirritating intradermal skin test concentrations for commonly prescribed antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003:112(3):629-630. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01783-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sousa-Pinto B, Tarrio I, Blumenthal KG, et al. Accuracy of penicillin allergy diagnostic tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(1):296-308. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Acker WW, et al. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome and multiple drug allergy syndrome: epidemiology and associations with anxiety and depression. Allergy. 2018;73(10):2012-2023. doi: 10.1111/all.13440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(17):1628-1635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wulf NR, Matuszewski KA. Sulfonamide cross-reactivity: is there evidence to support broad cross-allergenicity? Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(17):1483-1494. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khan DA, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Sulfonamide hypersensitivity: fact and fiction. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2116-2123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Queries Used in the Different Electronic Bibliographic Databases

eTable 2. Characteristics of Included Cohort Studies

eTable 3. Characteristics of Case Reports Included

eTable 4. Risk of Bias of Individual Studies