Key Points

Question

Are subtle impairments in systolic function, based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and strain, associated with heart failure (HF) risk in late life?

Findings

In this community-based cohort study, among 3552 older adult participants, 983 (27.7%) had 1 or more of the following: LVEF less than 60%, longitudinal strain less than 16.0%, and/or circumferential strain (less than 23.7%, although LVEF was less than 50% in only 50 (1.4%.) At a median of 5.5 years of follow-up, values of LVEF, longitudinal strain, and circumferential strain below these thresholds were each associated with incident HF and HF with reduced ejection fraction independent of clinical comorbidities, diastolic function, and each other.

Meaning

Current routine assessments of LV function may substantially underestimate the prevalence of prognostically important impairments in systolic function in late life.

Abstract

Importance

Limited data exist regarding the association of subtle subclinical systolic dysfunction and incident heart failure (HF) in late life.

Objective

To assess the independent associations of subclinical impairments in systolic performance with incident HF in late life.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study was a time-to-event analysis of participants without heart failure in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a prospective, community-based cohort study, who underwent protocol echocardiography at the fifth study visit (January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2013). Findings were validated independently in participants in the Copenhagen City Heart Study (CCHS). Data analysis was performed from June 1, 2018, to February 28, 2020.

Exposures

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), longitudinal strain (LS), and circumferential strain (CS) measured by 2-dimensional and strain echocardiography.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Main outcomes were incident adjudicated HF and HF with preserved and reduced LVEF at a median follow-up of 5.5 years (interquartile range, 5.0-5.8 years). Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for demographics, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking, coronary disease, estimated glomerular filtration rate, LV mass index, e′, E/e′, and left atrial volume index. Lower 10th percentile limits were determined in 374 participants free of cardiovascular disease or risk factors.

Results

Among 4960 ARIC participants (mean [SD] age, 75 [5] years; 2933 [59.0%] female; 965 [19%] Black), LVEF was less than 50% in only 76 (1.5%). In the 3552 participants with complete assessment of LVEF, LS, and CS, 983 (27.7%) had 1 or more of the following findings: LVEF less than 60%, LS less than 16.0%, or CS less than 23.7%. Modeled continuously or dichotomized, worse LVEF, LS, and CS were each independently associated with incident HF. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) per SD decrease in LVEF was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.29-1.55); the HR for LVEF less than 60% was 2.59 (95% CI, 1.99-3.37). Similar findings were observed for continuous LS (HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.22-1.53) and dichotomized LS (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.46-2.55) and for continuous CS (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.22-1.57) and dichotomized CS (HR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.64-3.22). Although the magnitude of risk for incident HF or death associated with impaired LVEF was greater using guideline (HR, 2.99; 95% CI, 2.19-4.09) compared with ARIC-based limits (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.58-2.25), the number of participants classified as impaired was less (104 [2.1%] based on guideline thresholds compared with 692 [13.9%] based on LVEF <60%). The population-attributable risk associated with LVEF less than 60% was 11% compared with 5% using guideline-based limits, a finding replicated in 908 participants in the CCHS.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that relatively subtle impairments of systolic function (detected based on LVEF or strain) are independently associated with incident HF and HF with reduced LVEF in late life. Current recommended assessments of LV function may substantially underestimate the prevalence of prognostically important impairments in systolic function in this population.

This cohort study assesses the independent associations of subclinical impairments in systolic performance with incident heart failure in late life in patients without heart failure.

Introduction

The prevalence and incidence of heart failure (HF) increases with age.1 Aging is also associated with increases in left ventricular (LV) mass,2 decreases in chamber size,3 and increases in chamber-level measures of systolic function, such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and fractional shortening.3 Left ventricular strain detects impairments in systolic deformation despite preserved LVEF,4 and older age is associated with decrements in systolic deformation5 and reserve6 despite higher LVEF.7 These impairments are associated with incident HF in the general population8 and outcomes in people with prevalent HF.9,10 Together, these findings suggest that assessment of LVEF alone, particularly when using existing lower limits of normal derived largely from younger samples (<52% for men and <54% for women based on American Society of Echocardiography [ASE] guidelines11), may underestimate the prevalence of clinically relevant systolic dysfunction in older adults. We studied older adults from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study who underwent comprehensive echocardiography at the fifth study visit to examine normative values for systolic measures (LVEF, longitudinal strain [LS], and circumferential strain [CS]) and assess their associations with incident HF and HF phenotype. We validated our findings in an independent cohort (Copenhagen City Heart Study [CCHS]).

Methods

Study Population

ARIC is an ongoing, prospective cohort study whose design and methods have been previously described in detail.12 Between 1987 and 1989, a total of 15 792 middle-aged individuals were enrolled from 4 communities in the US: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Washington County, Maryland. From January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2013, a total of 6538 of 10 330 surviving participants returned for a fifth study visit that included echocardiography and laboratory testing. This analysis included 4971 participants who underwent echocardiography and were free of prevalent HF at visit 5. Data analysis was performed from June 1, 2018, to February 28, 2020. The study protocol was approved by institutional review boards at each field center, and all participants provided written informed consent. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

To define reference limits for LV systolic measures, we identified a low-risk subgroup of participants free of prevalent cardiovascular disease or risk factors as previously described.13 This subgroup was defined based on the absence of prevalent cardiovascular disease (HF, coronary heart disease [CHD], atrial fibrillation, and moderate or greater valve disease), hypertension, diabetes, body mass index greater than 30 or less than 18 (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 mL/min/1.73 m2), QRS duration of greater than or equal to 120 milliseconds, or active smoking.

Assessment of Clinical Covariates

Prevalent cardiovascular disease included CHD (history of myocardial infarction, coronary intervention, or regional wall motion abnormality on visit 5 echocardiography), prevalent HF or atrial fibrillation, and moderate or greater aortic or mitral valve disease on visit 5 echocardiography. Prevalent HF was based on hospitalization with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) discharge code of 428 before 2005,14 with additional physician adjudication since 2005 as previously described.15 Prevalent atrial fibrillation was based on electrocardiograms at visits 1 through 5 and hospital discharge records as described previously.16 Prevalent hypertension and diabetes were based on blood pressure and serum glucose measured at visits 1 through 5, self-report, and medication use.

Echocardiography

Design and methods of echocardiography at ARIC visit 5 have previously been described, including reproducibility metrics for LVEF, LV volumes, and strain.17 Echocardiograms were performed by certified study sonographers using uniform imaging equipment and acquisition protocol. Quantitative measures were performed by blinded analysts at a dedicated core laboratory according to ASE recommendations.11,18 Additional details are provided in the eMethods in the Supplement. The LVEF was derived from LV volumes calculated by the modified Simpson method using the apical 4- and 2-chamber views (n = 4833). If apical image quality was inadequate for LV volume measurement, LVEF was calculated from LV dimensions using the Teichholz formula (n = 133): V = D^3∙7/(2.4 + D) where V is volume and D is dimension.19 The LVEF was visually estimated by board-certified echocardiographers (A.M.S. and H.S.) in 5 participants with inadequate image quality for accurate measurement of volumes and dimensions. The TomTec Cardiac Performance Analysis package was used to measure LS on 2-dimensional apical 4- and 2-chamber images and CS on short axis midpapillary level images that were acquired at 50 to 80 frames per second.

Ascertainment of Incident HF Events

Incident HF after visit 5 was based on ARIC HF event classification as previously described,15 which includes comprehensive abstraction of medical records (including information on LVEF) from hospitalizations with a potential HF-related ICD-9 code and subsequent physician adjudication (eMethods in the Supplement). Heart failure with preserved LVEF was defined as adjudicated HF with an LVEF of 50% or greater at the incident HF hospitalization and HF with reduced LVEF (HFrEF) if LVEF was less than 50% at incident HF hospitalization. Deaths were ascertained by ARIC surveillance of the National Death Index.20

Independent Replication Cohort: CCHS

The CCHS study is a Danish prospective cohort study.8,21,22 We included 908 participants from the echocardiographic substudy of the fourth CCHS examination (2001-2003) 65 years or older and free of prevalent HF. The LVEF was calculated from LV dimensions using the Teichholz formula.19 Participants were followed up in the Danish registries for incident HF or death until October 2014 using ICD-9 codes as described previously.8

Statistical Analysis

We used quantile regression (STATA qreg) to determine the 10th and 90th percentile limits (with associated 95% CIs) of the distribution of LV volumes, LVEF, LS, and CS in the low-risk subgroup (n = 374) overall and stratified by sex consistent with prior studies in older adults.23,24,25,26,27 These reference limits were then applied to the overall ARIC sample (n = 4971). Self-reported race was not significantly associated with reference limits in quantile regression models adjusted for sex and race, and race did not significantly modify the association between sex and reference limits. Supplemental analyses were performed using the fifth, as opposed to 10th, percentile limit to define reference limits.

Among ARIC participants free of prevalent HF at visit 5, associations of LVEF, LS, and CS with log-transformed N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and incident HF events (HF overall, HF with preserved LVEF [HFpEF], HFrEF, and composite of HF or death) during a median follow-up of 5.5 years (interquartile range [IQR], 5.0-5.8) were assessed using multivariable linear and Cox proportional hazards regression. Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking, history of CHD, atrial fibrillation, body mass index, eGFR, use of hypertension and antidiabetes medications, excessive drinking (defined as ≥14 drinks per week),28 and history of cancer. Cox proportional hazards regression models additionally adjusted for LV mass index, e′, E/e′, and left atrial volume index. For risk of incident HFpEF, participants developing HFrEF or HF with unknown LVEF were censored at the time of the HF event and vice versa for incident HFrEF. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed assigning HF with unknown LVEF events as HFpEF or HFrEF. The proportionality assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals, and no violations were noted. Restricted cubic splines adjusted for age, sex, and race were used to evaluate for possible nonlinear associations with log-transformed NT-proBNP (4 knots) and incident HF (3 knots). The number of knots was selected to minimize the model Akaike information criterion (3-5 knots tested). Among the 3552 participants with complete data for all 3 systolic measures (LVEF, LS, and CS) and free of prevalent HF, we assessed the association between number of impaired systolic measures and incident HF or death. To assess the impact of potential bias attributable to visit 5 nonattendance, we performed additional sensitivity analysis using inverse probability of attrition weighting (IPAW) as described in the eMethods in the Supplement.29,30 To assess the impact of missing LS and CS data, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation by chained equations as described in the eMethods in the Supplement.31

We determined the population-attributable risk (PAR) for death or incident HF associated with impaired LVEF defined using ARIC limits or the ASE guideline thresholds (<52% for men and <54% for women).11 The PARs were calculated using the STATA punaf command as follows: PAR% = pdi × [(RRi - 1)/RRi], where pdi is the proportion of total cases in the population in the ith exposure category and RRi is the adjusted relative risk for the ith exposure category. To replicate our findings with respect to LVEF, parallel analyses regarding the association of LVEF with proBNP concentrations and incident HF or death were performed in the CCHS cohort. Multivariable models in the CCHS were adjusted only for age and sex because the CCHS is a primarily White cohort.

A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with Stata software, version 14.2 (StataCorp, LLC).

Results

Among 4960 ARIC participants (mean [SD] age, 75 [5] years; mean [SD]; 2933 [59.0%] female; 965 [19%] Black), the LVEF was available in all participants, LS was available in 4672 participants, and CS was available in 3703 participants (Table 1). The mean (SD) LVEF was 65.7 (5.9%) and less than 50% in 76 participants (1.5%). The mean (SD) LS was 18.1 (2.4%), and the mean (SD) CS was 28.0 (3.6%).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of the ARIC Participants According HF Risk Factor Statusa.

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 4971) | Low-risk reference group (n = 374) | Participants with HF risk factors (n = 4579) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 75.3 (5.1) | 74.1 (4.6) | 75.4 (5.1) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 2933 (59.0) | 252 (67.4) | 2681 (58.5) | .003 |

| Black | 965 (19.4) | 26 (7.0) | 939 (20.5) | <.001 |

| Field center | ||||

| Forsyth County, North Carolina | 1195 (24.0) | 104 (27.8) | 1091 (23.8) | <.001 |

| Jackson, Mississippi | 869 (17.5) | 24 (6.4) | 845 (18.5) | |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 1547 (31.1) | 154 (41.2) | 1393 (30.4) | |

| Washington County, Maryland | 1360 (27.4) | 92 (24.6) | 1268 (27.7) | |

| Clinical covariates | ||||

| Hypertension | 4017 (80.8) | 0 | 4017 (87.7) | <.001 |

| Hypertension medication use | 3129 (62.9) | 0 | 3129 (68.3) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 1692 (34.0) | 0 | 1692 (37.0) | <.001 |

| Diabetes medication use | 845 (17.0) | 0 | 845 (18.5) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 1599 (32.2) | 0 | 1599 (34.9) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1241 (25.0) | 0 | 1241 (27.1) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 289 (5.8) | 0 | 289 (6.3) | <.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 496 (10.0) | 1 (0.3) | 495 (10.8) | <.001 |

| Current smoking | 284 (5.7) | 0 | 284 (6.2) | <.001 |

| Any prior smoking | 3009 (60.5) | 198 (52.9) | 2811 (61.4) | .002 |

| History of cancer | 158 (3.2) | 0 | 158 (3.4) | .003 |

| Excessive alcohol use | 108 (2.1) | 0 | 108 (2.4) | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.3 (5.4) | 24.9 (2.7) | 28.8 (5.6) | <.001 |

| BP, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 130 (18) | 121 (11) | 131 (18) | <.001 |

| Diastolic | 67 (10) | 64 (8) | 67 (10) | <.001 |

| Heart rate, mean (SD), beats/min | 62 (10) | 60 (8) | 62 (10) | <.001 |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| NT-proBNP, median (IQR), ng/mL | 116 (58-226) | 85 (52-150) | 120 (59-233) | <.001 |

| High-sensitivity troponin T, median (IQR), ng/L | 10.0 (7.0-15.0) | 8.0 (6.0-10.0) | 10.0 (7.0-15.0) | <.001 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, median (IQR), mg/L | 1.9 (0.9-4.1) | 1.3 (0.7-2.5) | 2.0 (1.0-4.1) | <.001 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 71 (16) | 78 (10) | 70 (17) | <.001 |

| Glycated hemoglobin, mean (SD), % | 5.9 (0.8) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.9 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Echocardiographic findings, mean (SD) | ||||

| LVEF, % | 65.7 (5.9) | 66.4 (4.8) | 65.5 (6.2) | .02 |

| End diastolic volume, mL | 80.7 (23.3) | 75.0 (18.9) | 81.2 (23.5) | <.001 |

| End systolic volume, mL | 28.1 (11.1) | 25.4 (8.1) | 28.3 (11.3) | <.001 |

| LV longitudinal strain, % | 18.1 (2.4) | 18.8 (2.2) | 18.1 (2.4) | <.001 |

| LV circumferential strain, % | 28.0 (3.6) | 28.1 (3.5) | 28.0 (3.6) | .60 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 77.9 (18.6) | 70.1 (13.5) | 78.5 (18.8) | <.001 |

| Septal E′, cm/s | 5.7 (1.5) | 6.2 (1.6) | 5.7 (1.5) | <.001 |

| E wave, cm/s | 66.6 (17.8) | 65.1 (15.6) | 66.7 (18.0) | .09 |

| Septal E/E′ | 12.2 (4.1) | 10.9 (3.1) | 12.3 (4.1) | <.001 |

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | 25.4 (8.5) | 22.8 (6.2) | 25.6 (18.6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide.

SI conversion factors: To convert C-reactive protein to milligrams per liter, multiply by 10; NT-proBNP to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1; and troponin T to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Reference Limits for Measures of Systolic Function

The 374 participants (7.5% of the study sample) in the low-risk reference subgroup were younger, with a lower percentage of men and Black individuals compared with the rest of the study sample (Table 1), and had lower NT-proBNP, high-sensitivity troponin T, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels. In the low-risk reference subgroup, the 10th percentile limit for LVEF was 60.4% for women and 59.6% for men; for the LS, the 10th percentile limit was 16.0% for women and 16.0% for men; and for CS, the 10th percentile limit was 24.0% for women and 22.8% for men (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Similar reference limits were found in analyses that incorporated IPAW (LVEF, 59.4% for women and 60.5% for men; LS, 16.0% for both women and men; CS, 22.9% for women and 24.1% for men) (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Systolic Measures and NT-proBNP Concentrations

In the overall study sample, LVEF was below the 60% reference limit in 692 of 4971 participants (13.9%), LS was below the 16% reference limit in 839 of 4672 (18.0%) with LS measurements, and CS was below the 23.7% reference limit in 377 of 3703 (10.2%) with CS measurements. The LVEF, LS, and CS values below the reference limits were more frequent in men compared with women and in Black compared with White participants (eTable 3 in the Supplement). At least 1 measure of LVEF or strain was impaired in 983 of 3552 participants (27.7%) with all 3 measures obtainable.

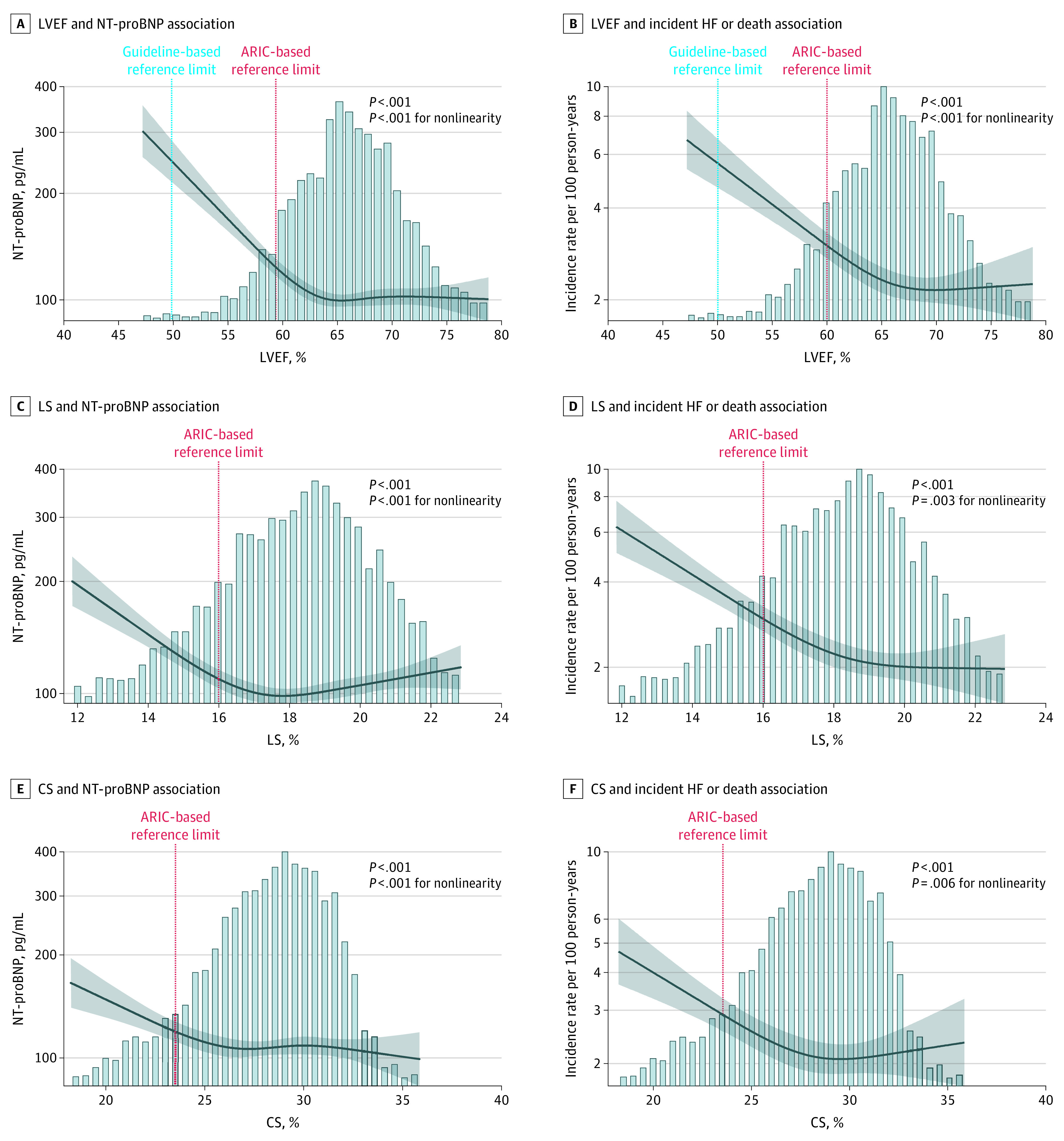

Lower LVEF, LS, and CS were each nonlinearly associated with higher NT-proBNP concentrations (Figure 1A, C, and E). A steeper increase in NT-proBNP concentrations was observed at values close to the ARIC-based reference limits. Sex significantly modified the association of LS and CS with NT-proBNP such that the association was stronger in men compared with women (eFigure in the Supplement). No significant effect modification by race was observed.

Figure 1. Association Between Left Ventricular Systolic Measures and N-Terminal Pro–B-Type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) and Incident Heart Failure (HF).

Restricted cubic splines show the association between measures of systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF], longitudinal strain [LS], and circumferential strain [CS]) and NT-proBNP and incident HF (incidence rate per 100 person-years), adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. ARIC indicates Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. The shading indicates 95% CIs.

Systolic Measures, Incident HF, and HF Phenotype

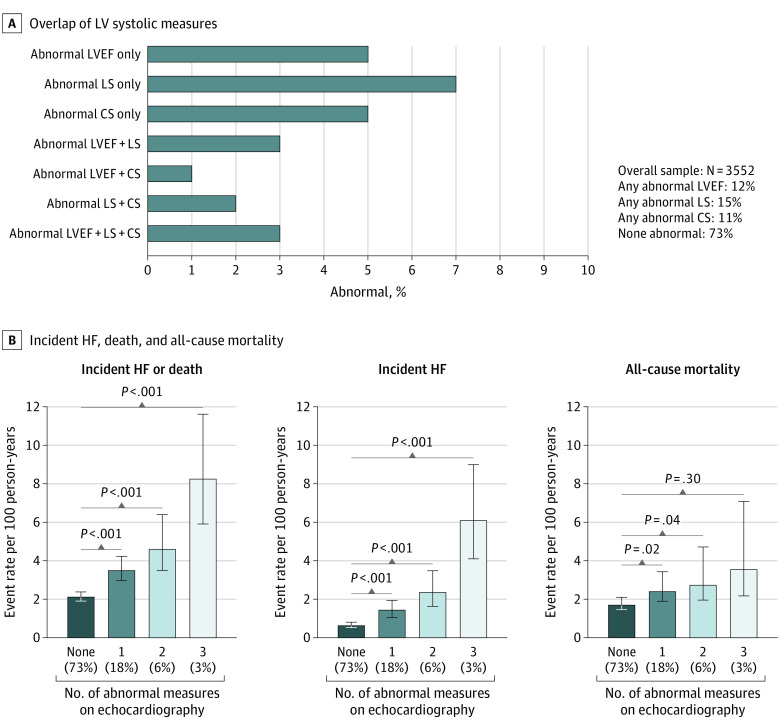

When modeled continuously and dichotomously using ARIC-based limits, lower LVEF, LS, and CS were each associated with a greater risk of incident HF or death in models adjusted for demographics (sex, age, and race), clinical covariates (hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking, prior myocardial infarction, and eGFR), and diastolic measures (e′, E/e′ ratio, left atrial volume index, and LV mass index) during a median follow-up of 5.5 years (IQR, 5.0-5.8 years) (Table 2; Figure 1B, D, and F), with similar magnitudes of effect for each systolic measure (HR per SD, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.12-1.29 for LVEF; HR per SD, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.10-1.29 for LS; and HR per SD, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.07-1.28 for CS). Both LS and CS remained associated with incident HF hospitalization after additional adjustment for LVEF (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The association between LVEF and incident HF was stronger in men than in women (HR per SD, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.34-1.70 for men; HR per SD, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.07-1.45 for women; P = .01 for interaction). No other effect modification by sex or race was observed. Lower values of LVEF, LS, and CS were more robustly associated with risk of incident HF vs all-cause mortality (HR per SD, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.27-1.55 vs HR per SD, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.99 – 1.17 for LVEF; HR per SD, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.55 vs HR per SD, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.99-1.19 for LS; HR per SD, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.21-1.55 and HR per SD, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.99-1.19 for CS) (Table 2). The mortality rate during this follow-up period was 2.2 (95% CI, 2.0-2.4) deaths per 100 person-years. In analyses that included all 3 systolic measures simultaneously (n = 3552), LVEF, LS, and CS values below the reference limits remained independently associated with incident HF (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.39-2.79 for LVEF; HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.57-2.99 for LS; and HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.18-2.48 for CS) (eTable 5 in the Supplement). The incidence of HF or death increased in a stepwise fashion with increasing number of systolic measures below the respective reference limits (Figure 2). However, when modeled continuously, only LVEF and LS remained independently associated with incident HF in simultaneous analyses of all 3 systolic variables (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.56 for LVEF; HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.16-1.56 for LS; and HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.93-1.25 for CS) (eTable 5 in Supplement). Similar results were observed in sensitivity analyses restricted to participants with measurable LVEF by Simpson’s method only (n = 4833) (eTable 6 in the Supplement) and excluding participants with interval myocardial infarction between baseline (visit 5) and time of HF hospitalization (n = 151) (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization and Heart Failure Phenotype Using ARIC-Based Reference Valuesa.

| Variable | No. of patients | No. (%) of events | Event rate (95% CI), per 100 PY | Adjusted for demographics and clinical covariates | Adjusted for demographics, clinical covariates, LVMi, and diastolic function | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) per 1-SD decrease | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) per 1-SD decrease | P value | ||||

| Incident heart failure hospitalization or death | |||||||||||

| LVEF, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 4279 | 587 (14) | 2.6 (2.4-2.8) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.26 (1.18-1.35) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.20 (1.12-1.29) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 692 | 175 (25) | 5.1 (4.4-6.0) | 1.63 (1.36-1.97) | 1.54 (1.27-1.86) | ||||||

| LS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3833 | 495 (13) | 2.4 (2.2-2.7) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.27 (1.18-1.37) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.19 (1.10-1.29) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 839 | 211 (25) | 4.9 (4.3-5.7) | 1.68 (1.41-2.00) | 1.50 (1.25-1.80) | ||||||

| CS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3326 | 441 (13) | 2.5 (2.3– 2.8) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.19 (1.09-1.30) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | .002 | 1.17 (1.07-1.28) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 377 | 87 (23) | 4.4 (3.6-5.4) | 1.58 (1.23-2.03) | 1.49 (1.15-1.91) | ||||||

| Incident heart failure hospitalization | |||||||||||

| LVEF, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 4279 | 194 (5) | 0.9 (0.7-1.0) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.58 (1.43-1.75) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.41 (1.27-1.55) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 692 | 96 (14) | 2.8 (2.3-3.4) | 2.68 (2.04-3.52) | 2.34 (1.77-3.09) | ||||||

| LS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3833 | 166 (4) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.63 (1.45-1.83) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.37 (1.21-1.55) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 839 | 107 (13) | 2.5 (2.1-3.0) | 2.55 (1.95-3.32) | 1.92 (1.44-2.55) | ||||||

| CS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3326 | 151 (5) | 0.9 (0.7-1.0) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.52 (1.33-1.74) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.41 (1.24-1.61) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 377 | 49 (13) | 2.5 (1.9-3.3) | 2.56 (1.79-3.66) | 2.18 (1.50-3.16) | ||||||

| All-cause mortality | |||||||||||

| LVEF, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 4279 | 464 (11) | 2.0 (1.8-2.2) | 1 [Reference] | .05 | 1.11 (1.03-1.21) | .01 | 1 [Reference] | .13 | 1.08 (0.99-1.17) | .07 |

| Impaired | 692 | 112 (16) | 3.1 (2.6-3.7) | 1.25 (1.00-1.57) | 1.20 (0.95-1.51) | ||||||

| LS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3833 | 384 (10) | 1.9 (1.7-2.0) | 1 [Reference] | .004 | 1.13 (1.04-1.24) | .01 | 1 [Reference] | .03 | 1.09 (0.99-1.19) | .07 |

| Impaired | 839 | 143 (17) | 3.2 (2.7-3.7) | 1.36 (1.10-1.67) | 1.27 (1.02-1.58) | ||||||

| CS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3326 | 346 (10) | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) | 1 [Reference] | .50 | 1.04 (0.94-1.15) | .43 | 1 [Reference] | .68 | 1.03 (0.94-1.14) | .51 |

| Impaired | 377 | 52 (14) | 2.5 (1.9-3.2) | 1.11 (0.81-1.52) | 1.07 (0.78-1.47) | ||||||

| Incident heart failure with LVEF ≥50% | |||||||||||

| LVEF, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 4279 | 106 (2) | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 1 [Reference] | .58 | 1.08 (0.90-1.29) | .42 | 1 [Reference] | .86 | 1.04 (0.87-1.23) | .68 |

| Impaired | 692 | 23 (3) | 0.7 (0.4-1.0) | 1.15 (0.69-1.92) | 1.05 (0.63-1.75) | ||||||

| LS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3833 | 90 (2) | 0.4 (0.4-0.5) | 1 [Reference] | .14 | 1.16 (0.96-1.39) | .12 | 1 [Reference] | .86 | 1.00 (0.83-1.20) | .98 |

| Impaired | 839 | 31 (4) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 1.40 (0.90-2.18) | 1.05 (0.65-1.69) | ||||||

| CS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3326 | 82 (2) | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 1 [Reference] | .88 | 0.88 (0.70-1.10) | .25 | 1 [Reference] | .74 | 0.85 (0.68-1.07) | .16 |

| Impaired | 377 | 10 (3) | 0.5 (0.3-0.9) | 1.05 (0.53-2.10) | 0.88 (0.43-1.81) | ||||||

| Incident heart failure with LVEF <50% | |||||||||||

| LVEF, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 4279 | 59 (1) | 0.3 (0.2-0.3) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 2.22 (1.96-2.52) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.90 (1.66-2.18) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 692 | 64 (9) | 1.9 (1.5-2.4) | 5.78 (3.89-8.60) | 4.71 (3.15-7.05) | ||||||

| LS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3833 | 51 (1) | 0.3 (0.2-0.3) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 2.34 (1.96-2.78) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 1.95 (1.62-2.35) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 839 | 64 (8) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 4.89 (3.26-7.34) | 3.63 (2.37-5.57) | ||||||

| CS, % | |||||||||||

| Not impaired | 3326 | 44 (1) | 0.3 (0.2-0.3) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 2.49 (2.08-2.98) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 2.24 (1.87-2.68) | <.001 |

| Impaired | 377 | 37 (10) | 1.9 (1.4-2.6) | 5.97 (3.62-9.82) | 5.09 (3.06-8.47) | ||||||

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; CS, circumferential strain; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; LS, longitudinal strain; LAVi, left atrial volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; PY, person-years.

Impaired LVEF was defined as less than 59.4% for women and less than 60.4% for men using 10th percentile limits in the low-risk subgroup. For LS, the cutoffs were 16.0% for women and 16.0% for men. Cutoffs for CS were 22.8% for women and 24.0% for men. Numbers of events, percentages, and the event rates are given for the normal (referent) and impaired (defined by ARIC cutoff) groups. The HRs from Cox proportional hazards regression models were adjusted for demographics (age, race, and sex), clinical covariates (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, body mass index, eGFR, use of hypertension and diabetes medications, excessive drinking, and history of cancer), LVMi, and diastolic function (septal e′, septal E/e′, and LAVi). Participants with heart failure events with an LVEF less than 50% or unknown LVEF at the time of heart failure hospitalization were censored in analyses with incident heart failure with an LVEF of 50% or greater as the end point. Conversely, heart failure events with an LVEF of 50% or greater or unknown LVEF at the time of heart failure hospitalization were censored in analyses with incident heart failure with LVEF less than 50% as the end point.

Figure 2. Distribution of Impaired Left Ventricular Systolic Measures and the Association With Incident Heart Failure (HF) or Death.

A, Percentage of abnormal measures for each measure of systolic function alone and combined in Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) participants free of HF at visit 5. The percentage of the study population who had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 50% was 1% (n = 50), of whom 35 had abnormal longitudinal strain (LS) and circumferential strain (CS), 9 had abnormal LS but not CS, and 3 had abnormal CS but not LS. The LVEF was less than 40% in 5 participants, all of whom also had abnormal LS and CS. B, Incidence rate (per 100 person-years) of HF or death according to number of impaired systolic measures. P values from Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, and field center are given. The error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Of the 290 participants who developed HF after visit 5, LVEF at the time of HF was 50% or greater in 129 (44.5%), less than 50% in 123 (42.4%), and not available in 38 (13.1%). Values of each systolic measure below its reference limit were associated with risk of incident HFrEF, even after adjustment for clinical covariates and diastolic measures (Table 2). Furthermore, LS and CS remained associated with HFrEF after further adjustment for LVEF (eTable 4 in the Supplement), and in analyses restricted to persons with LVEF greater than 60% (fully adjusted HR per 1 SD, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.15-2.03; P = .004 for LS; adjusted HR per 1 SD, 2.55; 95% CI, 1.79-3.63; P < .001 for CS). In contrast, systolic measures were not associated with incident HFpEF in adjusted models. These findings were consistent in analyses treating incident HF events with unknown LVEF as HFpEF or HFrEF (eTable 8 in the Supplement) and in models adjusting for fewer covariates (eTable 9 in the Supplement). Similar results for all time-to-event analyses were observed in the following sensitivity analyses: (1) using the fifth percentile limit in the low-risk reference group to define reference limits instead of the 10th percentile limit (eTable 10 in the Supplement); (2) incorporating IPAW (eTable 11 in the Supplement); (3) using multiple imputation for missing LS and CS data (eTable 12 in the Supplement); (4) adjusting for lateral or average, instead of septal, e′ and E/e′ (eTable 13 in the Supplement); and (5) adjusting for stable coronary disease and history of myocardial infarction separately (eTable 14 in the Supplement).

Validation of ARIC-Based Reference Limits for LVEF in the CCHS

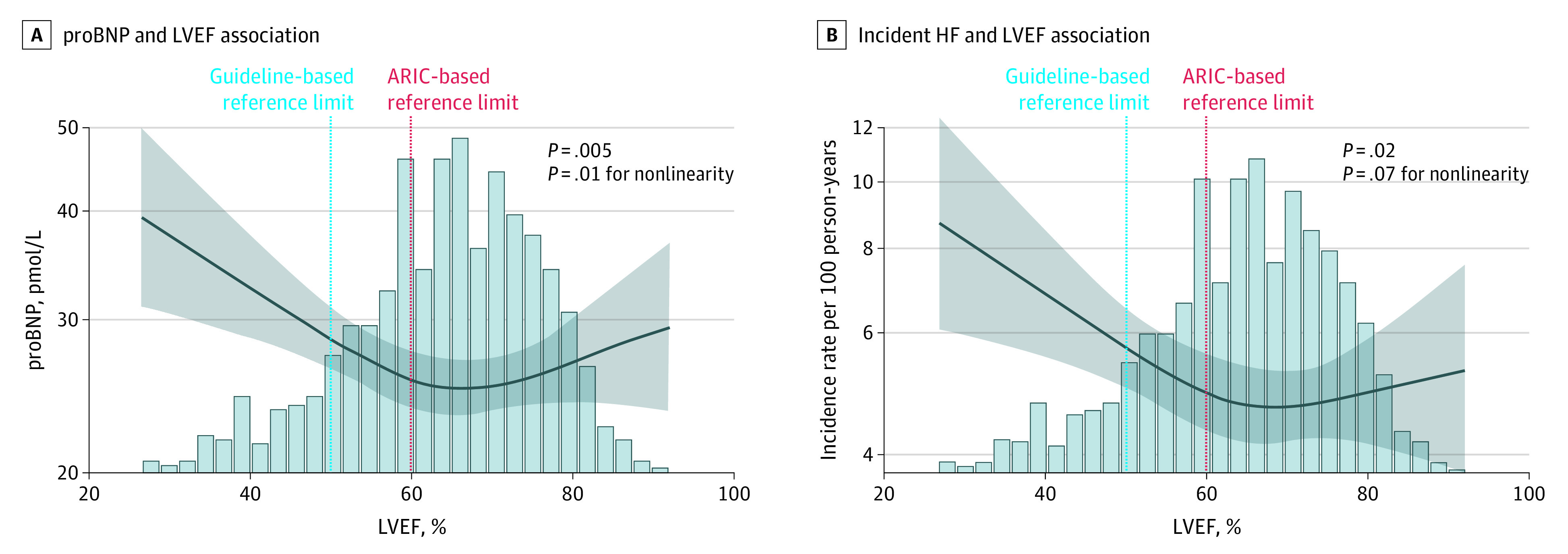

In ARIC, the association of LVEF with incident HF hospitalization or death was nonlinear, with a steeper increase in risk noted at an LVEF more closely approximating the ARIC-based reference limit compared with the guideline cutoff (Figure 1D). Among 908 participants 65 years or older without HF in the CCHS (mean [SD] age, 74.4 [6.3] years; 606 [66.7%] female) (eTable 15 in the Supplement), similar nonlinear associations were observed between LVEF and NT-proBNP (Figure 3A) and incident HF or death (Figure 3B), although the association with incident HF or death was not statistically nonlinear.

Figure 3. Association Between Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction and Outcomes in Participants 65 Years or Older in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Restricted cubic splines show the association between left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) (A) and incident heart failure (HF) (B) in participants of the Copenhagen City Heart Study. ARIC indicates Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. The shading indicates 95% CIs.

In ARIC, although the magnitude of risk for incident HF or death associated with impaired LVEF was greater using guideline thresholds (HR, 2.99; 95% CI, 2.19-4.09) compared with ARIC-based limits (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.58-2.25), the number of participants classified as impaired was less (104 [2.1%] based on guideline thresholds compared with 692 [13.9%] based on LVEF <60%). As a result, the PAR for incident HF or death associated with an impaired LVEF defined using the ARIC-based limits was 11% (95% CI, 7%-15%), whereas it was only 5% (95% CI, 3%-7%) using the guideline cut points. These findings were replicated in the CCHS, with a PAR for incident HF or death associated with impaired LVEF of 9% (95% CI, 2%-15%) using the ARIC-based definition and 4% (95% CI, 0%-9%) using the guideline definition.

Discussion

Contemporary echocardiographic data from this large, biracial, longitudinal cohort study of older adults suggest that lower values of LVEF, LS, and CS are associated with incident HF independent of clinical risk factors and with incident HFrEF in particular. Of importance, with the use of both LVEF and strain and the application of age-specific reference values, impairment in systolic function was detected in 983 participants (27.7%)—far more than the 104 (2.1%) with an LVEF less than 52% (in men) or less than 54% (in women). The ARIC-based reference limits for LVEF, LS, and CS identified participants at heightened risk for incident HF. Impairments of LVEF, LS, and CS did not completely overlap, and each provided additive risk of incident HF independent of the others. Together, these findings suggest that current recommended assessments of LV function substantially underestimate the prevalence of impaired systolic function in late life. The additive prognostic value of these measures suggests an important role for these relatively subtle impairments of systolic function (detected based on LVEF or strain) in identifying those at risk for HF in late life.

Longitudinal echocardiographic data from the Framingham Heart Study demonstrate that aging is associated with increases in LV wall thickness, decreases in LV cavity size, and increases in chamber-level measures of LV systolic function (LVEF and fractional shortening).3 Furthermore, traditional HF risk factors modify these normal age-related changes, and increases in wall thickness and mass are therefore exaggerated, cavity size fails to decrease, and increases in fractional shortening are attenuated.2,3 Concordant with these observations, the lower reference limit for LVEF, the most ubiquitous measure of LV systolic function, was 60% in the current study, which is higher than the 52% to 54% cut point recommended by practice guidelines.11 This higher value agrees well with the biplane LVEF reference values from the Normal Reference Ranges for Echocardiography study (lower limit of 57%), which also found higher LVEF with older age in both sexes.7

Although LVEF values above 45% to 50% have not been associated with the risk of adverse outcomes in prevalent HF,32 data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and the Framingham Heart Study demonstrate heightened risk of incident HF with an LVEF of 50% to 55% compared with greater than 55% in younger community-based cohorts (mean ages of 62 in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and 60 years in the Framingham Heart Study).32,33 In the older study sample in the current study (mean age, 75 years), lower LVEF was associated with higher incidence of HF hospitalization or death beginning at LVEF values of 60%, a pattern replicated in an independent cohort (CCHS). This higher reference limit is concordant with post hoc analyses of recent HFpEF clinical trials, which predominantly enrolled older adult patients, demonstrating that therapies effective for HFrEF, such as spironolactone34 and sacubitril-valsartan,35 appear to benefit HFpEF patients with LVEF less than 57% to 60% but not above these values. Together, these findings suggest that an LVEF of 50% to 55%, commonly termed low normal clinically, is abnormally low in older adults and associated with elevated HF risk.

Left ventricular strain appears to be a less load-dependent measure of systolic function than LVEF,4 and its measurement is becoming increasingly common in clinical echocardiography laboratories. Although worse LVEF predicts adverse outcomes in HFrEF but not HFpEF,36 impairments in LS are prognostically relevant in both HFrEF and HFpEF.9,10 In addition, impairments of both LS and CS are associated with incident HF in community-based studies.8,37 Concordant with these prior studies,8,37 both LS and CS were also associated with incident HF independent of LVEF—and each other—in our cohort. Furthermore, even when restricted to participants with an LVEF greater than 60% at visit 5, worse LS and CS were associated with risk of HFrEF. Both LS and CS were impaired in most participants with LVEF less than 50%. However, impairments of LVEF, LS, and CS did not completely overlap when age-appropriate reference limits were used, and a greater number of impaired measures was associated with higher risk of incident HF.

The mechanisms associating these relatively subtle impairments in systolic function with HF risk are unclear. Declines in LV diastolic function with age despite preserved LVEF are well recognized.13,38,39 Alterations in LS and CS at rest have been associated with impairments in LV diastolic reserve with exercise.40 Of importance, impairments in LVEF, LS, and CS were most robustly associated with risk of incident HFrEF, supporting the hypothesis that these modest impairments in LV systolic function may reflect early contractile dysfunction and herald worsening dysfunction and frank reductions in LVEF. Furthermore, although lower LVEF and impaired LV strain have been associated with coronary artery disease and with worse diastolic function, the associations of these measures with risk of HF, and incident HFrEF in particular, persisted in our study after excluding intercurrent myocardial infarctions and after accounting for LV mass and diastolic function with minimal effect attenuation. In contrast, concomitant alterations in LV mass and diastolic measures appeared to account for much of the association of impaired LVEF and LS with incident HFpEF.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Many ARIC participants died before visit 5. Because the analysis primarily focused on systolic function among persons surviving to late life, this was not a limitation. However, not all ARIC participants alive at visit 5 chose to participate, which may introduce attendance bias. Similar results with respect to reference limits and associations with HF risk were observed in sensitivity analyses that incorporated IPAW, although IPAW cannot fully correct for the impact of attendance bias. Left ventricular ejection fraction was not available at the time of HF hospitalization in a few participants, similar to other epidemiologic studies,40,41,42,43 but sensitivity analyses that treated these HF cases as HFpEF or HFrEF demonstrated consistent results with our primary analysis (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Left ventricular ejection fraction may have been overestimated because of nontomographic echocardiographic imaging. However, experienced sonographers acquired all images, the references limits were concordant with those derived in the Normal Reference Ranges for Echocardiography study,7 and the findings are consistent in 2 independent cohorts with LVEF measured with different methods. Also, this method of LVEF assessment is by far the most commonly used clinically. Left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated by the Teichholz method in the CCHS, which is a limitation of the replication cohort. Although lower values of LVEF, LS, and CS were associated with incident HF independent of each other, this analysis does not address the incremental value of LS and CS beyond LVEF for HF risk prediction. Measures of cardiorespiratory fitness were not available in ARIC at visit 5. In addition, some strain data were missing because of image quality, particularly for CS, which limited the power for multivariable modeling, especially for incident HFpEF or HFrEF. The magnitude of missingness is similar to that observed in other community-based studies,37,44 and similar findings were observed in analyses that used multiple imputation (eTable 12 in the Supplement). Models for incident HFpEF and HFrEF may have been overfit; however, similar results were observed in models that adjusted for fewer covariates (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that among elderly people living in the community, worse LVEF, LS, and CS are independently associated with incident HF and with incident HFrEF in particular. Age-appropriate reference limits were associated with impaired LVEF (<60%) in 13.9%, and the incorporation of LS and CS was associated with a prognostically relevant impairment in systolic function in 27.7% of participants. Relatively subtle impairments of systolic function, detected based on LVEF or strain, appear to be associated with development of HF in late life and are likely substantially underdetected by current routine assessments of LV function.

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Percentile Limits for the Distribution of Echocardiographic Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function Among the Low-Risk Subgroup (n = 374)

eTable 2. Distribution of Echocardiographic Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function Among the Low-Risk Subgroup in Analyses Incorporating Inverse Probability of Attrition Weights

eTable 3. Prevalence of Impaired LV Systolic Function According to ARIC-Based Reference Limits in Participants Without Prevalent Heart Failure (N = 4971); Overall and Stratified by Gender and Race

eTable 4. Association of Impaired Measures of Longitudinal and Circumferential Strain With Death, Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization, and Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusted for Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Using ARIC-Based Reference Values

eTable 5. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization Using ARIC-Based Reference Values in 3,552 Participants With Complete Data for All Three Echocardiographic Measures

eTable 6. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization Using ARIC-Based Reference Values Restricted to Participants With Simpson’s EF

eTable 7. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Heart Failure in 4,820 Participants Without and Interim MI

eTable 8. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Heart Failure Phenotype With Unknown LVEF Treated as Either HfpEF or HfrEF Events

eTable 9. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusted for a More Restrictive Set of Clinical Characteristics

eTable 10. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization and Heart Failure Phenotype Using ARIC-Based Reference Values Based on 5th Percentile Limits

eTable 11. Inverse Probability of Attrition Weighting for the Association Between Impaired Measures of Systolic Function and Incident Heart Failure With LVEF Above and Below 50%

eTable 12. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization and Heart Failure Phenotype Using ARIC-Based Reference Values With Imputation for Longitudinal and Circumferential Strain Using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations

eTable 13. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Incident Heart Failure and Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusted for Lateral E′ and Lateral E/e′ as well as E′ and E/Septal and Lateral E′

eTable 14. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization and Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusting for Stable Coronary Disease and History of MI

eTable 15. Baseline Characteristics of Participants Aged ≥65 Years With No Prevalent Heart Failure From the Copenhagen City Heart Study

eFigure. Relationship of Longitudinal and Circumferential Strain Stratified by Male (A & C) and Female (B & D) Sex

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieb W, Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, et al. Longitudinal tracking of left ventricular mass over the adult life course: clinical correlates of short- and long-term change in the framingham offspring study. Circulation. 2009;119(24):3085-3092. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.824243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng S, Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, et al. Correlates of echocardiographic indices of cardiac remodeling over the adult life course: longitudinal observations from the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;122(6):570-578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.937821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah AM, Solomon SD. Myocardial deformation imaging: current status and future directions. Circulation. 2012;125(2):e244-e248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.086348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, Richart T, et al. Left ventricular strain and strain rate in a general population. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(16):2014-2023. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleg JL, O’Connor F, Gerstenblith G, et al. Impact of age on the cardiovascular response to dynamic upright exercise in healthy men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78(3):890-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kou S, Caballero L, Dulgheru R, et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal cardiac chamber size: results from the NORRE study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15(6):680-690. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biering-Sørensen T, Biering-Sørensen SR, Olsen FJ, et al. Global longitudinal strain by echocardiography predicts long-term risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in a low-risk general population: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(3):e005521. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, et al. Prognostic importance of impaired systolic function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and the impact of spironolactone. Circulation. 2015;132(5):402-414. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sengeløv M, Jørgensen PG, Jensen JS, et al. Global longitudinal strain is a superior predictor of all-cause mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(12):1351-1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(3):233-270. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The ARIC Investigators . The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687-702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah AM, Claggett B, Kitzman D, et al. Contemporary assessment of left ventricular diastolic function in older adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2017;135(5):426-439. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):1016-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Baggett C, et al. Classification of heart failure in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: a comparison of diagnostic criteria. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(2):152-159. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonso A, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, et al. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and African-Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2009;158(1):111-117. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah AM, Cheng S, Skali H, et al. Rationale and design of a multicenter echocardiographic study to assess the relationship between cardiac structure and function and heart failure risk in a biracial cohort of community-dwelling elderly persons: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(1):173-181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, et al. ; Houston, Texas; Oslo, Norway; Phoenix, Arizona; Nashville, Tennessee; Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Uppsala, Sweden; Ghent and Liège, Belgium; Cleveland, Ohio; Novara, Italy; Rochester, Minnesota; Bucharest, Romania; and St. Louis, Missouri . Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(12):1321-1360. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teichholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: echocardiographic-angiographic correlations in the presence of absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37(1):7-11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, et al. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: methods and initial two years’ experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(2):223-233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goetze JP, Mogelvang R, Maage L, et al. Plasma pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in the general population: screening for left ventricular hypertrophy and systolic dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(24):3004-3010. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mogelvang R, Sogaard P, Pedersen SA, et al. ; SA MRSPP . Cardiac dysfunction assessed by echocardiographic tissue Doppler imaging is an independent predictor of mortality in the general population. Circulation. 2009;119(20):2679-2685. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.793471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makam AN, Nguyen OK, Xuan L, Miller ME, Goodwin JS, Halm EA. Factors associated with variation in long-term acute care hospital vs skilled nursing facility use among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):399-405. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischman DA, Yang J, Arfanakis K, et al. Physical activity, motor function, and white matter hyperintensity burden in healthy older adults. Neurology. 2015;84(13):1294-1300. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim AS, Kowgier M, Yu L, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Sleep fragmentation and the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in older persons. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1027-1032. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Kirshner M, Shen C, Dodge H, Ganguli M. Serum anticholinergic activity in a community-based sample of older adults: relationship with cognitive performance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):198-203. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M. Descriptive anthropometric reference data for older Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(1):59-66. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00021-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonçalves A, Claggett B, Jhund PS, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of heart failure: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(15):939-945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):119-128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318230e861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gottesman RF, Rawlings AM, Sharrett AR, et al. Impact of differential attrition on the association of education with cognitive change over 20 years of follow-up: the ARIC neurocognitive study. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(8):956-966. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeboah J, Rodriguez CJ, Qureshi W, et al. Prognosis of low normal left ventricular ejection fraction in an asymptomatic population-based adult cohort: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Card Fail. 2016;22(10):763-768. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsao CW, Lyass A, Larson MG, et al. Prognosis of adults with borderline left ventricular ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(6):502-510. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solomon SD, Claggett B, Lewis EF, et al. ; TOPCAT Investigators . Influence of ejection fraction on outcomes and efficacy of spironolactone in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(5):455-462. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al. ; PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1609-1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solomon SD, Anavekar N, Skali H, et al. ; Candesartan in Heart Failure Reduction in Mortality (CHARM) Investigators . Influence of ejection fraction on cardiovascular outcomes in a broad spectrum of heart failure patients. Circulation. 2005;112(24):3738-3744. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng S, McCabe EL, Larson MG, et al. Distinct aspects of left ventricular mechanical function are differentially associated with cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in the community. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(10):e002071. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC Jr, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289(2):194-202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, et al. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2011;306(8):856-863. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senni M, Tribouilloy CM, Rodeheffer RJ, et al. Congestive heart failure in the community: a study of all incident cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota, in 1991. Circulation. 1998;98(21):2282-2289. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.21.2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):251-259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, et al. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):260-269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lam CS, Lyass A, Kraigher-Krainer E, et al. Cardiac dysfunction and noncardiac dysfunction as precursors of heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction in the community. Circulation. 2011;124(1):24-30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.979203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugimoto T, Dulgheru R, Bernard A, et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal left ventricular 2D strain: results from the EACVI NORRE study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18(8):833-840. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Percentile Limits for the Distribution of Echocardiographic Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function Among the Low-Risk Subgroup (n = 374)

eTable 2. Distribution of Echocardiographic Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function Among the Low-Risk Subgroup in Analyses Incorporating Inverse Probability of Attrition Weights

eTable 3. Prevalence of Impaired LV Systolic Function According to ARIC-Based Reference Limits in Participants Without Prevalent Heart Failure (N = 4971); Overall and Stratified by Gender and Race

eTable 4. Association of Impaired Measures of Longitudinal and Circumferential Strain With Death, Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization, and Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusted for Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Using ARIC-Based Reference Values

eTable 5. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization Using ARIC-Based Reference Values in 3,552 Participants With Complete Data for All Three Echocardiographic Measures

eTable 6. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization Using ARIC-Based Reference Values Restricted to Participants With Simpson’s EF

eTable 7. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Heart Failure in 4,820 Participants Without and Interim MI

eTable 8. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Heart Failure Phenotype With Unknown LVEF Treated as Either HfpEF or HfrEF Events

eTable 9. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusted for a More Restrictive Set of Clinical Characteristics

eTable 10. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization and Heart Failure Phenotype Using ARIC-Based Reference Values Based on 5th Percentile Limits

eTable 11. Inverse Probability of Attrition Weighting for the Association Between Impaired Measures of Systolic Function and Incident Heart Failure With LVEF Above and Below 50%

eTable 12. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization and Heart Failure Phenotype Using ARIC-Based Reference Values With Imputation for Longitudinal and Circumferential Strain Using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations

eTable 13. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Incident Heart Failure and Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusted for Lateral E′ and Lateral E/e′ as well as E′ and E/Septal and Lateral E′

eTable 14. Association of Impaired Measures of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Death or Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization and Heart Failure Phenotype Adjusting for Stable Coronary Disease and History of MI

eTable 15. Baseline Characteristics of Participants Aged ≥65 Years With No Prevalent Heart Failure From the Copenhagen City Heart Study

eFigure. Relationship of Longitudinal and Circumferential Strain Stratified by Male (A & C) and Female (B & D) Sex