Abstract

Objectives and Methods:

With 432,513 samples from UK biobank dataset, multivariable linear/logistic regression were used to estimate the relationship between psoriasis/PsA and eBMD/osteoporosis, controlling for potential confounders. Here, confounders were set in three ways: model0 (including age, height, weight, smoking and drinking), model1 (model0+regular physical activity) and model2 (model1+medication treatments). The estimated bone mineral density (eBMD) was derived from heel ultrasound measurement. And 4,904 psoriasis patients and 847 PsA patients were included in final analysis. Mendelian randomization (MR) approach was used to evaluate the causal effect between them.

Results:

Lower eBMD were observed in PsA patients than in controls in both model0 (β-coefficient=−0.014, P=0.0006) and model1 (β-coefficient=−0.013, P=0.002), however, the association disappeared when conditioning on treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin (model2) (β-coefficient=−0.0005, P=0.28), mediation analysis showed that 63% of the intermediary effect on eBMD was mediated by medication treatment (P<2E-16). Psoriasis patients without arthritis showed no difference of eBMD compared to controls. Similarly, the significance of higher risk of osteopenia in PsA patients (OR=1.27, P=0.002 in model0) could be eliminated by conditioning on medication treatment (P=0.244 in model2). Psoriasis without arthritis was not related to osteopenia and osteoporosis. The weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) analysis found that genetically determined psoriasis/PsA were not associated with eBMD (P=0.34 and P=0.88). Finally, MR analysis showed that psoriasis/PsA had no causal effect on eBMD, osteoporosis and fracture.

Conclusions:

The effect of PsA on osteoporosis was secondary (e.g., medication) but not causal. Under this hypothesis, psoriasis without arthritis was not a risk factor for osteoporosis.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Psoriatic arthritis, Bone mineral density, Osteoporosis, Osteopenia, Mendelian randomization, UK biobank

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin disease characterized by infiltration of immune cells into the epidermis and abnormal expressions of keratinocytes1. It affects around 2.5% of the Europeans, 0.05–3% Africans and 0.1–0.5% Asians2–5. One of the most severe comorbidities of psoriasis is psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which is presented with joint pain, stiffness and swelling, and affects 0.4–1% of the UK populations6,7. Both psoriasis and PsA have a strong genetic component. Estimating from twin and family studies in European populations, the heritability of psoriasis is about 60–90%8,9, while the heritability of PsA is up to 80–100%10,11. So far, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified more than 60 susceptibility loci for psoriasis and explained about 28% of the genetic heritability12. GWAS for PsA have identified more than 20 SNPs and explained about 10% of the genetic heritability13.

Previous observational studies have investigated the associations between psoriasis/PsA and osteoporosis/fracture. Kathuria et al conducted a large-scale cross-sectional study including 183,725 individuals with psoriasis and 28,765 individuals with PsA in the United States and found that patients with psoriasis/PsA had significantly higher odds of diagnosis with osteopenia, osteoporosis and fractures14. More interestingly, Dreiher et al showed a sex-specific association in a case–control Israel study (7,936 psoriasis cases and 14,835 controls) that the prevalence of osteoporosis was significantly higher in males with psoriasis, but not among females15. On the other hand, Keller et al indicated that patients with osteoporosis had a significantly higher prevalence of previously diagnosed psoriasis, through a population-based case–control (17,507 osteoporosis cases and 52,521 controls) study in Taiwan16. However, the consensus was not always reached, Kocijan et al found that trabecular bone mineral density was significantly decreased in German patients with PsA than controls, whereas no significant result was observed in patients with psoriasis17. Recently, Modalsli et al performed a population-based Norwegian study (48,194 individuals with 2,804 psoriasis cases), and found no increased risk of fracture and low BMD (total hip, femoral neck and lumbar spine) in psoriasis patients18. Busquets et al found there was no difference for lumbar spine BMD between the PsA patients and the Spanish general population, but the sample size of this study was small19. Therefore, there was still debate on whether the psoriasis/PsA were risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture20, thus, it would be necessary to understand the relationship between them, to provide evidence for clinicians to make their decisions on whether psoriasis/PsA patients should be screened for low bone mineral density or whether proper management should be provided to reduce the fracture risk for the patients with psoriasis/PsA, especially in elderly.

While there were several reasons for the inconsistent findings, unknown confounding factors for psoriasis in an observational design could lead to controversial results in different studies21. Although randomized controlled trial (RCT) design could be a gold standard method for identifying causality, it was time and money consuming. However, with public availability of genetic data for complex diseases, Mendelian randomization (MR) design could be an alternative but cost-efficient approach to investigate the causal relationship between exposure and outcome22,23, the MR method was similar with a natural RCT, which used the genetic variants as instrumental variables to explore the causal inference on an exposure-outcome associations24. The Previous MR studies had identified a bunch of risk factors for osteoporosis25, such as the causal effect of lowering LDL-C levels on BMD26, and the relationship of inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and BMD/fracture27.

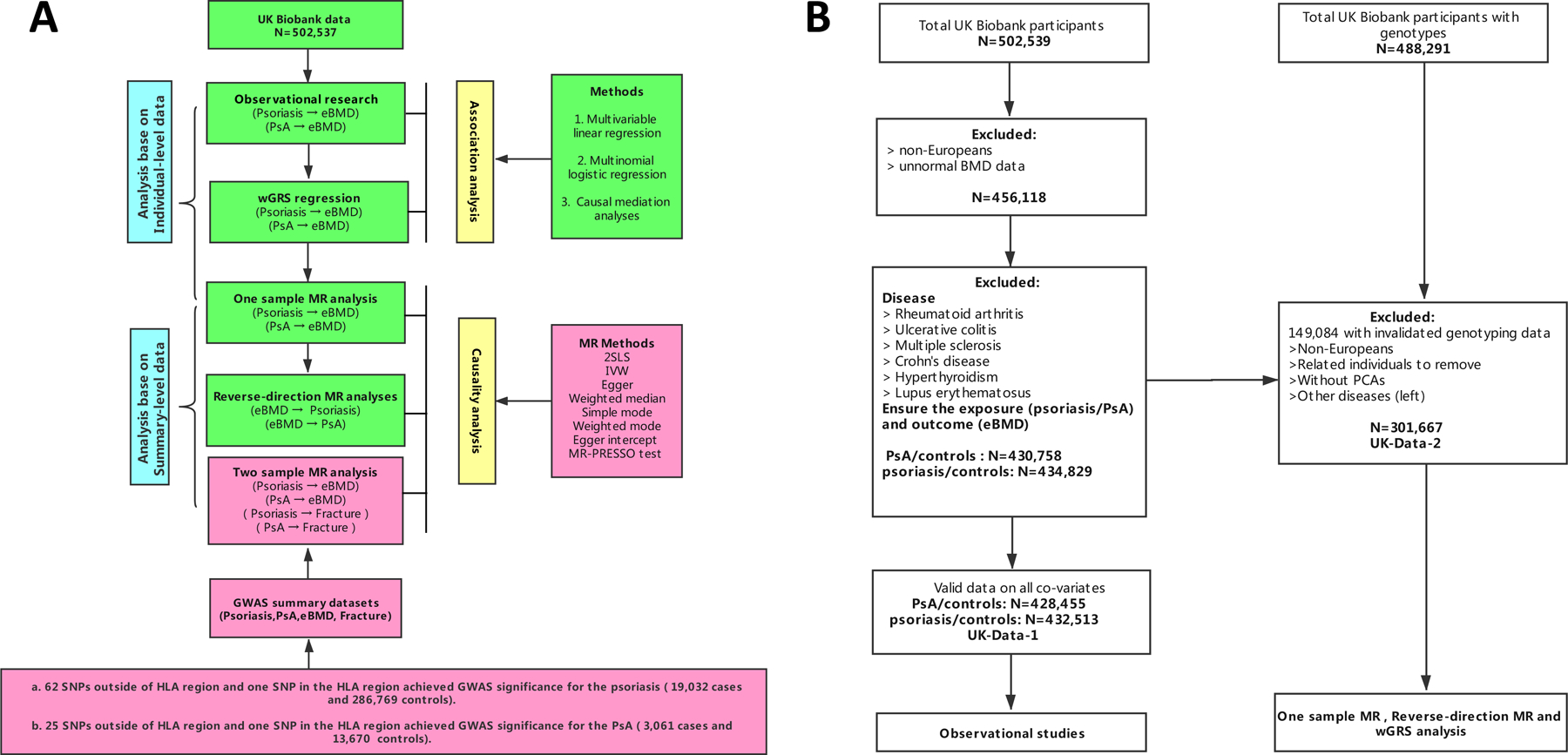

In the present study, we first examined the relationship of psoriasis, PsA with BMD through a population based observational study and a weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) method using UK Biobank individual-level dataset. Then, with the summary-statistic GWAS data of psoriasis, PsA and BMD, we implemented MR approach and the reverse-direction MR to detect the causal relationship between psoriasis and BMD. An overview of the study design was illustrated in Figure 1A. In addition, we also performed two sample MR analysis to estimate the causal effects of the psoriasis, PsA on the fracture risk.

Figure 1. Study design overview (A) and the quality control of participants (B).

wGRS, weighted genetic risk score, 2SLS, two-stage least-squares regression, MR, Mendelian Randomization, HLA region, humanleukocyte antigen region, eBMD, heel bone mineral density, IVW, inverse variance-weighted method, MR-PRESSO, MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier test.

Note: The green color was analysed in the UK biobank dataset, the light red was using the publicly available data.

Methods

Individual-level data from UK Biobank

The individual-level data were available from the large population-based UK Biobank dataset imputed to 1000 Genomes Project28, which was from the same data application used in previous study (Application ID 41376)29. All individuals provided written informed consent. North West Multi-center Research Ethics Committee approved the UK Biobank ethical application30. The details of the data extraction from UK Biobank were described in the online Supplementary Text. In brief, we used ICD code to extract phenotype data such as psoriasis/PsA (Supplementary Table S1) and eBMD. We excluded participants if they were diagnosed with one of the diseases including multiple sclerosis, crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, hyperthyroidism, lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis (Supplementary Table S2). We finally obtained two datasets UK-Data-1 and UK-Data-2 in the analysis (Supplementary Text, Supplementary Table S3–S4). The quality control process was shown on Figure 1B.

Summary-statistic data

The summary-statistic data of psoriasis/PsA, BMD and fracture were applied in the two sample MR analysis. In this study, the summary-level datasets were obtained from published GWAS for psoriasis (19,032 cases and 286,769 controls)12, PsA (3,061 cases and 13,670 controls)13, eBMD (462,824) and fracture risk (45,087 cases and 317,775 controls)31 (Supplementary Table S5). The details of instrumental SNPs selection for psoriasis, PsA and eBMD were described in the online Supplementary Text. In brief, 60 SNPs for psoriasis, 25 SNPs for PsA and 973 SNPs for eBMD were selected in the MR analysis. It should be noted that some instrumental SNPs were not presented in Morris et al31, then proxy SNPs that were highly correlated with the reported SNPs (r2 > 0.90) were used (Supplementary Table S6).

Observational studies

Within the UK Biobank dataset, we performed a cross-sectional study to detect the association between the psoriasis/PsA and eBMD/osteopenia/osteoporosis. Firstly, we implemented a multivariable linear regression to estimate the relationship between psoriasis/PsA (exposure) and eBMD in UK-Data-1 dataset, controlling for potential confounders, here we set the confounders in three ways: model0 (including age, height, weight, smoking status and drinking status), model1 (model0+regular physical activity) and model2 (model1+medication treatments).

Next, we grouped the eBMD-T score into three categories according to the World Health Organization criterion as follows, normal bone density (T score > −1.0), low bone density or osteopenia (−1.0 >= T score > −2.5) and osteoporosis (T score <= −2.5), then, we performed a multinomial logistic regression to evaluate the relationship between psoriasis/PsA (exposure) and osteoporosis/osteopenia in UK-Data-1, here, we set normal BMD, osteopenia and osteoporosis as 0, 1, 2. We analyzed the data by using the R software (https://www.r-project.org/). The multinomial logistic regression was implemented by using the “nnet” package in R.

Furthermore, we performed a mediation analysis to explore whether the relationship between PsA (exposure) and eBMD (outcome) could be explained, at least partially, by an intermediate variable (mediator). Here we set the medication treatments or regular physical activity as the mediator from the prior knowledge20. We applied the causal mediation analysis (CMC) method to dissect total effect of exposure into direct and indirect effect32,33, and to examine the indirect effect which was transmitted via mediator to the outcome. The mediation analysis was performed using the R packages of “mediation” and adjusting the age, height, weight, smoking status and drinking status.

Weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) analysis

Within the UK Biobank dataset, we applied weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) method to estimate the effect of psoriasis/PsA SNPs on eBMD and psoriasis itself. The wGRS method formula was:

the βi was the effect estimate of the ith SNP derived from Tsoi et al12 and Stuart et al13, N here was 60 for the psoriasis or 25 for the PsA (the instrumental SNPs selected). We extracted the genotypes from UK-Data-2. We first estimated whether the instruments were suitable for the MR analysis, then, the multivariable linear regression (implemented in R package) were employed to evaluate the association between psoriasis/PsA-wGRS and eBMD within the UK biobank individual level dataset by adjusted for age, sex, height and weight. The score method was performed using PLINK software (http://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2), here, we used the option --score sum to obtain the sum of valid per-allele scores.

Mendelian randomization analysis

One sample MR analysis

Within the UK Biobank dataset, we implemented a standard MR analysis to estimate the causal effect of the psoriasis/PsA on the eBMD (change in eBMD per doubling log odds of psoriasis). To be specific, a two-stage least-squares (2SLS) regression was performed, at the first stage, we got the predicted values of psoriasis regressed on the genetic instruments (outside of the HLA region or HLA region), then, we regressed the eBMD on the predicted values from the first stage by using a liner regression34. The covariates we selected were age, sex, height and weight. The 2SLS method was implemented by using the “ivpack” package in R software (https://www.r-project.org/).

Two sample MR analysis

With the published summary-statistic datasets of psoriasis/PsA and eBMD/fracture, we performed two sample MR analysis to estimate the causal relationship between psoriasis/PsA and eBMD/fracture. The genetic variants used in instrumental variable analysis for psoriasis and PsA were shown in Supplementary Table S7 and S8. Please note that for the SNP rs28512356 with incompatible allele, it was excluded from the analysis (the effect/non-effect alleles were C/G for psoriasis/PsA and C/A for fracture risk). The details of different MR methods were described in the online Supplementary Text.

Reverse-direction MR analysis

We performed a reverse-direction MR analysis to estimate the effect of eBMD (exposure) on psoriasis/PsA (Figure 1B). The 973 genetic instruments for eBMD were extracted from Morris et al31 (Supplementary Table S9). We performed multivariate logistic analysis for psoriasis/PsA in UK-Data-2, and the effect size (coefficients/odds ratios) of the SNPs were extracted as summary statistic data.

To be noted, for binary exposures, the estimate values should be multiplied by 0.693 to demonstrate the change in eBMD per doubling in odds of psoriasis or PsA. All of the analyses were conducted in R version 3.5.1. The MR analysis were performed using the R packages of “MendelianRandomization”35, “TwoSampleMR”36 and “MR-PRESSO”37.

Results

Observational analysis in UK biobank

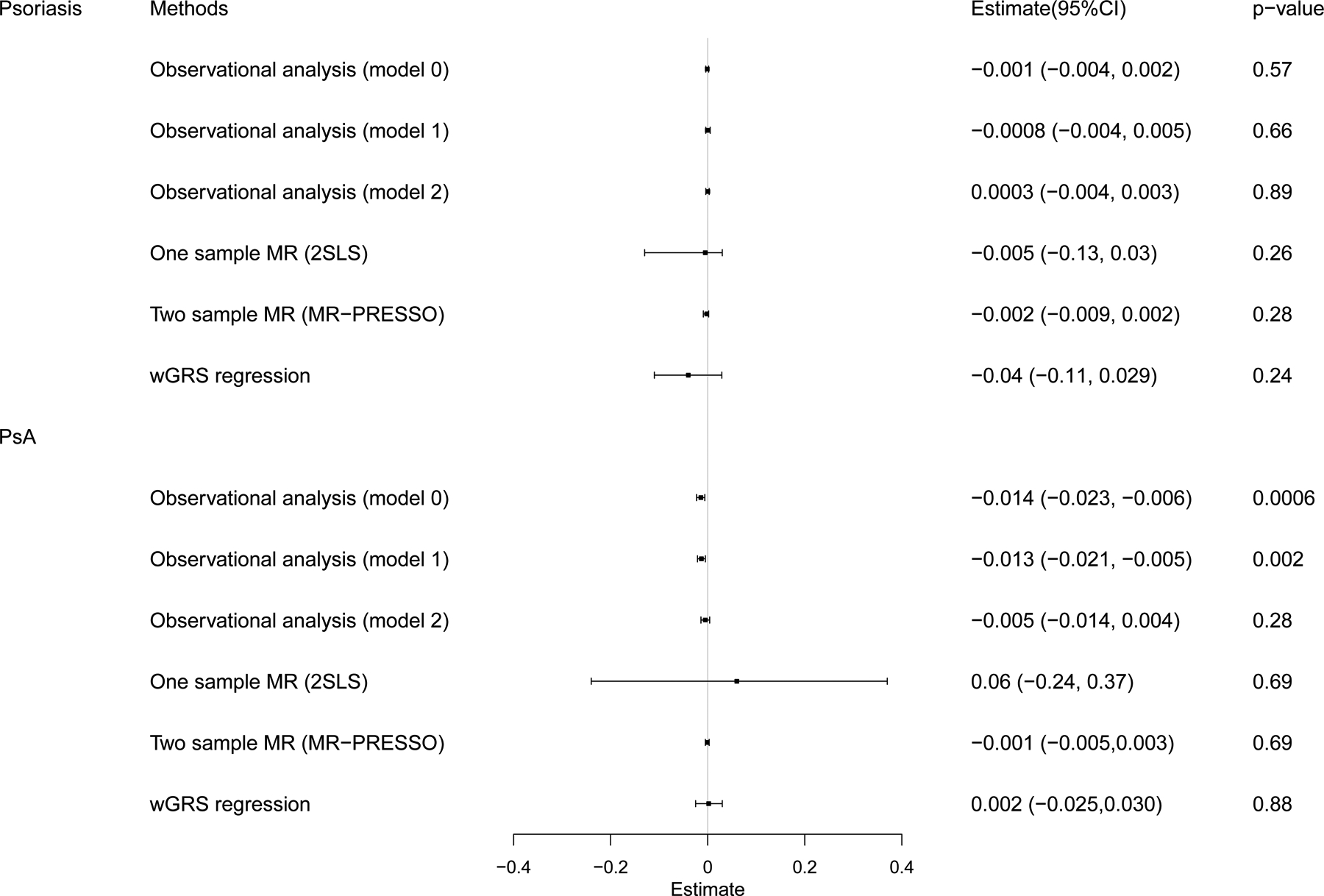

We found that PsA was associated with low eBMD in pooled samples (male and female) by using multivariable linear regression adjusted for confounders such as adjusted for age, sex, height, weight, smoking status and drinking status (model0) (β-coefficient=−0.014 [95% CI −0.023 to −0.006], P = 0.0006) (Figure 2 and Table 1). However, when regular physical activity was included as an additional covariable (model1), the association became less significant (β-coefficient=−0.013 [95% CI −0.021 to −0.005], P = 0.002), and this association disappeared when conditioning on treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin (model2) (P=0.28) (Figure 2 and Table 1). The casual mediation analysis indicated that 63% of the intermediary effect on eBMD was mediated by the medication treatments (indirect effect = −0.009, P<2E-16), while the proportion of total effect via mediation of the regular physical activity was only 8% (Table 2). We did not observe any relationship between psoriasis and eBMD (P > 0.05 in all models) (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2. Summary of effect estimates from the different methods for the psoriasis and PsA on eBMD.

CI, confidence interval, wGRS, weighted genetic risk score, MR, Mendelian Randomization.

Table 1.

The differences of eBMD between psoriasis/PsA cases and controls.

| Disease | Sex | Model | β- coefficient (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis (without PsA) | Male and Female | Model0 | −0.001 (−0.004, 0.002) | 0.57 |

| Model1 | −0.0008 (−0.004 to 0.005) | 0.66 | ||

| Model2 | 0.0003 (−0.004, 0.003) | 0.89 | ||

| Female | Model0 | −0.002 (−0.007, 0.002) | 0.33 | |

| Model1 | −0.002 (−0.007 to 0.002) | 0.34 | ||

| Model2 | −0.002 (−0.007, 0.003) | 0.42 | ||

| Male | Model0 | −0.0001 (−0.005, 0.005) | 0.98 | |

| Model1 | 0.0001 (−0.005 to 0.0055) | 0.84 | ||

| Model2 | 0.002 (−0.004, 0.006) | 0.62 | ||

| PsA | Male and Female | Model0 | −0.014 (−0.023, −0.006) | 0.0006 |

| Model1 | −0.013 (−0.021, −0.005) | 0.002 | ||

| Model2 | −0.005 (−0.014, 0.004) | 0.28 | ||

| Female | Model0 | −0.012 (−0.023, −0.001) | 0.03 | |

| Model1 | −0.009 (−0.02, 0.0014) | 0.09 | ||

| Model2 | −0.007 (−0.019, 0.005) | 0.25 | ||

| Male | Model0 | −0.017 (−0.029, −0.004) | 0.008 | |

| Model1 | −0.015 (−0.027, −0.003) | 0.02 | ||

| Model2 | −0.002 (−0.016, 0.012) | 0.81 |

Model0 = Linear regression of eBMD on psoriasis/PsA adjusted for age, sex, height, weight, smoking status, drinking status.

Model1 = Linear regression of eBMD on psoriasis/PsA adjusted for age, sex, height, weight, smoking status, drinking status, regular physical activity.

Model2 = Linear regression of eBMD on psoriasis/PsA adjusted for age, sex, height, weight, smoking status, drinking status, regular physical activity, treatments with methotrexate or ciclosporin.

UK-Data-1 was used in this analysis

Table 2.

Assessment of the mediators (regular physical activity and medication treatment) for the association between PsA and eBMD.

| Mediator | Effect | Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular physical activity | ACME | −0.001 | −0.002 | 0.00 | <2E-16 |

| ADE | −0.013 | −0.02 | 0.00 | <2E-16 | |

| Total Effect | −0.014 | −0.02 | 0.00 | <2E-16 | |

| Prop. Mediated | 0.086 | 0.047 | 0.23 | <2E-16 | |

| Medication treatments | ACME | −0.009 | −0.012 | −0.01 | <2E-16 |

| ADE | −0.005 | −0.011 | 0.00 | 0.32 | |

| Total Effect | −0.014 | −0.02 | −0.01 | <2E-16 | |

| Prop. Mediated | 0.63 | 0.43 | 1.29 | <2E-16 |

ACME: Average Causal Mediation Effect [total effect - direct effect]

ADE: Average Direct Effect [total effect - indirect effect]

Total Effect: Direct (ADE) + Indirect (ACME)

Prop. Mediated: Conceptually ACME / Total effect

When stratified by gender, male PsA patients had lower eBMD than male controls in both model0 (β-coefficient = −0.017, 95% CI [−0.029 to −0.004], P = 0.008) and model1 (β-coefficient −0.015 [95% CI −0.027 to −0.003], P = 0.02), similarly, the association disappeared in model2 (Table 1). We observed that the effect of PsA on eBMD in male was a little larger than in female, however, the difference between male and female did not reach statistical significance (P=0.547 for model0 and P=0.459 for model1). Again, we did not observe any relationship between psoriasis and eBMD in both male and female (P > 0.05 in all models) (Table 1).

In addition, the effects of psoriasis/PsA on osteoporosis/osteopenia were estimated using the multinomial logistic regression model. We found significant higher risk of osteopenia in both model0 (OR=1.27, 95% CI 1.09–1.47, P = 0.002) and model1 (OR=1.25, 95% CI 1.07–1.45, P = 0.004) in patients with PsA (Supplementary Table S10). Similarly, the significance of higher risk of osteopenia in patients with PsA could be eliminated by conditioning on medication treatment (model2) (Supplementary Table S10). When we stratified by sex, we found that PsA were significantly related to male osteopenia in model0 and model1, but not in model2 (Supplementary Table S10). In addition, we found psoriasis was not related to osteopenia and osteoporosis in any model for both male and female (Supplementary Table S10).

Weighted genetic risk score analysis

We found psoriasis wGRS of 60 SNPs was strongly associated with psoriasis in UK Biobank data (OR = 2.10; 95% CI 2.03–2.17, P < 1.0E-300). Similarly, PsA wGRS of 25 SNPs showed significant association with PsA (OR = 1.57; 95% CI 1.53–1.61, P = 9.8E-260). These results indicated the instruments were powerful for the MR analysis.

When we regressed the observed eBMD on the psoriasis-wGRS, and found there was no significant association (β- coefficient −0.04 [95% CI −0.11 to 0.029], P = 0.24) (Figure 2 and Table 3). Similar results were observed for PsA-wGRS (β- coefficient 0.002 [95% CI −0.025 to 0.030], P = 0.88) (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

The associations of genetic determined psoriasis/PsA with eBMD by using different MR methods.

| Estimate (95% CI) | P | Q’ p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis → eBMD | |||

| One-sample MR | |||

| 2SLS | −0.005 (−0.13, 0.03) | 0.26 | |

| wGRS | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.029) | 0.24 | |

| Two sample MR | |||

| IVW | −0.003 (−0.01, 0.002) | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| Simple mode | −0.004 (−0.02, 0.008) | 0.41 | |

| Weighted mode | −0.006 (−0.02, 0.001) | 0.10 | |

| Weighted median | −0.006 (−0.01, −0.001) | 0.01 | |

| MR-Egger | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) | 0.10 | |

| MR-Egger intercept | −0.001 (−0.001, 0.004) | 0.20 | |

| MR-PRESSOa | −0.002 (−0.009, 0.002) | 0.28 | 0.22 |

| PsA → eBMD | |||

| One-sample MR | |||

| 2SLS | 0.06 (−0.24, 0.37) | 0.69 | |

| wGRS | 0.002(−0.025,0.030) | 0.88 | |

| Two sample MR | |||

| IVW | 0.001 (−0.004, 0.006) | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Simple mode | −0.002 (−0.01, 0.005) | 0.48 | |

| Weighted mode | −0.002 (−0.009, 0.004) | 0.46 | |

| Weighted median | −0.001 (−0.007, 0.003) | 0.48 | |

| MR-Egger | 0.004(−0.003, 0.01) | 0.21 | |

| MR-Egger intercept | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.001) | 0.19 | |

| MR-PRESSOb | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.003) | 0.69 | 0.23 |

Estimate (95% CI): A regression coefficient and its 95% confidence interval.

2SLS: Two stage least-squares (2SLS) regression.

IVW: Inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method.

MRPRESSO: MR method for correcting for pleiotropy residual sum and outlier.

Q’ p-value: Test for Heterogeneity of IVW and MR-PRESSO after outlier pleiotropy SNPs.

IV outliers detected: rs17812953, rs2510066, rs34536443, rs5754387, rs7184567

IV outliers detected: rs34536443.

Mendelian randomization analysis of psoriasis/PsA on eBMD and fracture

In the MR analysis using instruments outside the HLA region, we did not find evidence to show statistically significant association of genetically increased PsA risk with eBMD utilizing one-sample 2SLS MR algorithm (P=0.69) (Figure 2 and Table 3). And two-sample MR results consistently suggested no causal effect between PsA on eBMD (P>0.05 in all methods) (Figure 2 and Table 3). There was heterogeneity in IVW results (Q’ P<0.001), when we excluded pleiotropic variants using restrictive MR-PRESSO method, but still, no causal association was detected between PsA and eBMD (P=0.69). For psoriasis and eBMD, one-sample MR results and most of the two-sample MR results showed no causal effect of psoriasis on eBMD, except a trend of association by using weighted median method (Table 3).

We only used two-sample MR analysis to assess the causal effect of Psoriasis/PsA on facture risk, and the results suggested both psoriasis and PsA had no causal association with facture (P>0.05 in any of the two-sample MR methods) (Supplementary Table S11).

In addition, we used SNP in the HLA region (rs13200483 for psoriasis and rs13214872 for PsA) as the instrument to performed the MR analysis to assess the causal association between psoriasis/PsA and eBMD. The results were consistent with the MR results observed by using instruments outside HLA region, that there were no causal effects of the psoriasis/PsA on the eBMD in one-sample 2SLS MR analysis (psoriasis: β-coefficient=0.002 [95% CI −0.058 to 0.062], P=0.95 and PsA: β-coefficient=−0.09 [95% CI −0.48 to 0.30], P=0.65) (Supplementary Table S12).

Reverse-direction Mendelian randomization analysis of eBMD on psoriasis/PsA

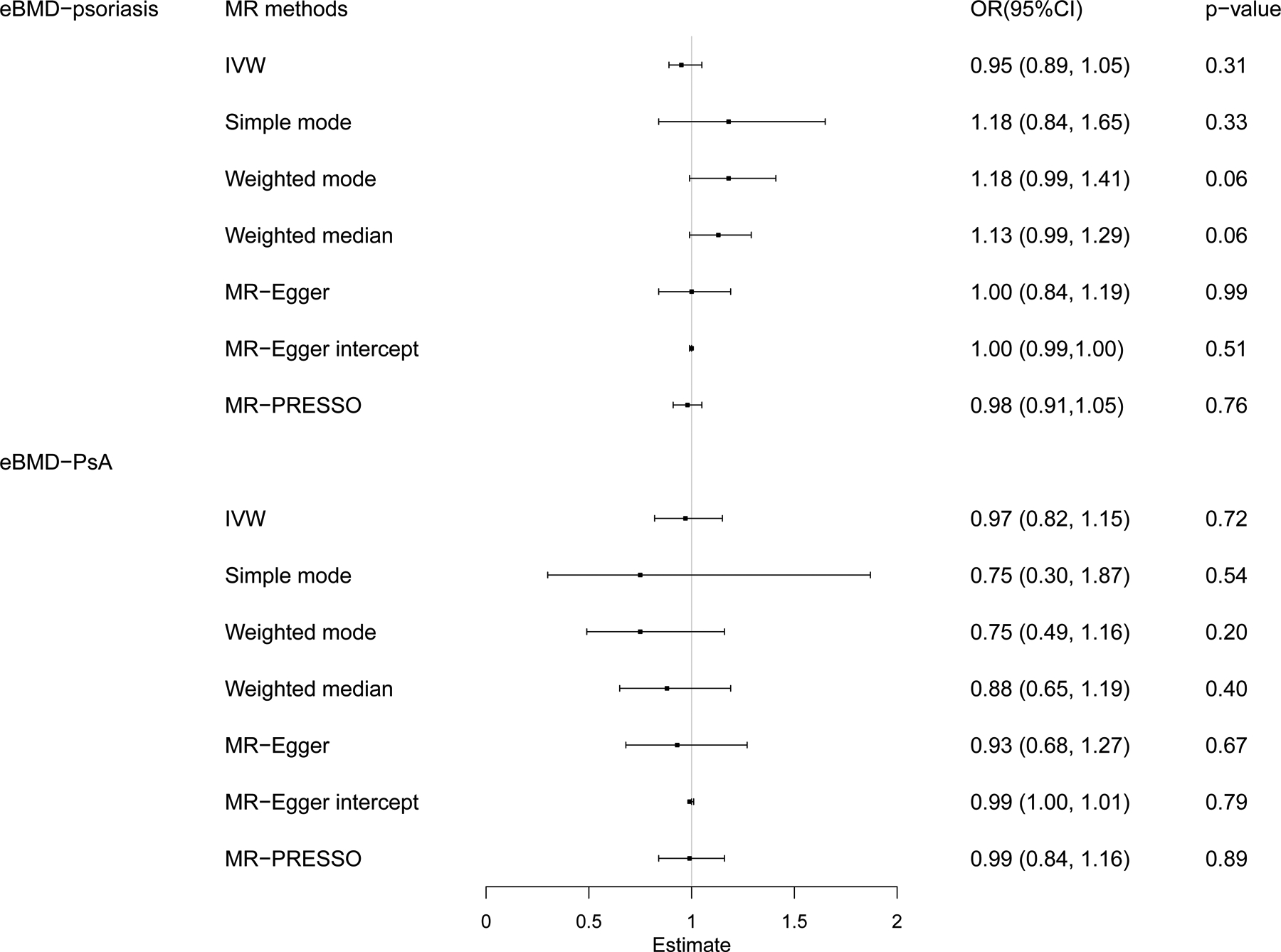

We also estimated the causal effects of eBMD on psoriasis/PsA by using the reverse-direction MR analysis. After removing outlier variants with MR-PRESSO method, the results showed that the genetically instrumented eBMD was not associated with psoriasis (ORs ranged from 0.89 to 1.05, all P > 0.05) and PsA (ORs ranged from 0.82 to 1.15, all P > 0.05) (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S13).

Figure 3. Association of eBMD with the psoriasis and PsA using reverse-direction MR analysis.

IVW, inverse variance-weighted method, MR-PRESSO, MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier test.

Discussion

The link between psoriasis/PsA and osteoporosis remains unclear. Benefited from large-scale UK Biobank dataset, we conducted a cross-sectional study to investigate the relationship between psoriasis/PsA and BMD/osteoporosis. By analysing hundreds of thousand samples, we found that PsA disease somehow associated with low BMD, but this association partially intermediate by treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin in PsA patients. Further wGRS and mendelian randomization analysis suggested that the association between PsA and BMD/osteoporosis/fracture observed in cross-sectional study was not genetically determined, which also suggested a secondary effect of PsA on osteoporosis (e.g. medication). Psoriasis, not including PsA, was not associated with low BMD and osteoporosis in both observational study and mendelian randomization analysis. And vice versa. Level of eBMD had no causal effect on psoriasis and PsA.

The UK Biobank dataset enabled us to detect the relationship between psoriasis/PsA and BMD with a considerable statistical advantage. The prevalence of psoriasis and PsA in UK biobank dataset were estimated to be 1.59% and 0.29%, this was consistent with the previous studies (psoriasis: 1.3% to 2.2% and PsA: 0.4% to 1%) in UK populations6,7, suggesting UK Biobank dataset could reflect the UK population well. Previous observational study found PsA was associated with osteopenia, osteoporosis and osteomalacia in a cross-sectional study including 28,765 PsA patients14. Ogdie et al38 discovered that PsA was associated with an elevated risk for fracture in a population-based cohort study including 9,788 PsA patients. Borman et al39 detected psoriatic patients with peripheral arthritis with longer duration of joint disease might be at a risk for osteoporosis. We also found that lower eBMD were observed in PsA patients than controls, and the higher risk of osteopenia and was observed in patients with PsA, but in the present study, we did further investigation and found that this association partially intermediate by treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin in PsA patients, suggesting the effect of PsA on osteoporosis was secondary.

Furthermore, by using wGRS and mendelian randomization analysis, we found genetically increased PsA risk had no causal effect on eBMD, which confirmed the hypothesis of “secondary effect”. We speculated that systemic use of antipsoriatic drugs in PsA patients (such as methotrexate and cyclosporin), had been revealed to affect the process of bone remodeling16,40,41, Moreover, PsA patients sometimes accompanied with pain, swelling and immobilization in one or more joints, thus, less physical activities were taken in these patients, and lack of physical exercise might cause bone loss in PsA patients.

Previous study15 found that psoriasis was associated with osteoporosis among males, but not among females. Here, we observed that the effect of PsA on eBMD in male was a little larger than in female. As we know, bone mass was believed to considerably increase during the first decades, and women were more likely to suffer from osteoporosis after menopause because of declining of estrogen levels42. In the present study, the mean age of female participants was 56.6 (± 8.11) years, that was, most of them were after menopause, which meant most of them had experienced bone loss already. We supposed that, because most of the females were after menopause, the effect of PsA on the BMD/osteoporosis was slacked by declined hormone levels. However, the difference between male and female did not reach statistical significance in our study (P=0.547 for model0 and P=0.459 for model1). In general, women after menopause were encouraged to check their bone mineral density, and our results suggested that males who suffered from the PsA should also be screened for bone mineral density and osteoporosis, especially for those who received treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin.

On the other hand, there was no difference of eBMD between psoriasis patients and controls in our study. As we discussed above, the association between PsA and BMD was not genetically determined, therefore, the psoriasis patients (not PsA) without secondary condition wound not suffer bone loss. These results were consistent with some previous observational studies. Modalsli et al18 observed that there was no association between psoriasis and risk of fracture, in addition, they did not find higher prevalence of osteoporosis among patients with psoriasis in a large population-based prospective study (2,804 psoriasis). Pedreira et al43 found that psoriasis patients did not present lower BMD in a cross-sectional study containing 52 psoriasis women and 98 healthy female controls. Although our results indicated that psoriasis patients without peripheral arthritis might not be under risk of osteoporosis, it did not mean that patients with psoriasis did not need to care about bone health.

In addition, we conducted a systematic MR analyses to assess the relationship between psoriasis/PsA and osteoporosis, as MR method might better account for possible confounders and biases. However, we found no causal effects for the two exposures (psoriasis and PsA) on the eBMD in either one-sample MR or two-sample MR analysis. Similarly, the reverse-direction MR analysis also suggested no causal relationship for the eBMD on the psoriasis and PsA. Further, we did not find causal effect of psoriasis/PsA on fracture risk. Therefore, the association between PsA and osteoporosis observed in cross-sectional study was confirmed to be secondary but not causal.

Though, we performed a systematic MR analysis in the research, the MR results should be explained carefully. Firstly, the instruments implemented in MR approach should have no horizontal pleiotropy, therefore, in our study, we applied different classical sensitivity analyses to detect the potential pleiotropic effects in one-sample, two-sample MR analysis and reverse-direction MR analysis using these sensitivity methods44,45. Secondly, we should select the suitable SNPs as instrumental variables, otherwise the inappropriate instrumental variables might undermine the effectiveness of the research46. Here, the GWAS studies, in which we selected our instruments, were under large-scale design, and thus provided powerful instrumental variables for the MR analysis. In addition, we also used a SNP rs13200483 (HLA-C*06:02) alone as an instrument, which was strongly associated with psoriasis, similarly, a SNP rs13214872 (HLA-C*06:02) was also used alone as an instrument for the PsA analysis47–49. The MR analyses using different instruments (one HLA SNP alone or all SNPs excluding the HLA SNP) obtained approximately the same results for the psoriasis and PsA.

In this large-scale observational study, we found that PsA disease might be a risk factor for low BMD, but this effect partially intermediate by treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin. Systematic MR analysis and wGRS analysis also suggested that the association between PsA and BMD/osteoporosis/fracture was not genetically determined but secondary (e.g. medication). Therefore, psoriasis patients (not including PsA) without secondary condition might not be under risk of osteoporosis. These results suggested that, in clinical practice, psoriatic arthritis patients should be screened for osteopenia and osteoporosis and proper management should be provided to reduce the fracture risk, especially for those who received treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and self-reported codes for psoriasis and PsA in UK Biobank.

Supplementary Table S2. The International Classification of Diseases(ICD) codes and self-reported codes for excluded diseases.

Supplementary Table S3. Characteristics of participants of psoriasis/controls in UK-Data-1.

Supplementary Table S4. Characteristics of participants of PsA/controls in UK-Data-1.

Supplementary Table S5. The characteristics of the studies for the summary-statistic data.

Supplementary Table S6. The proxy SNPs exhibited to replace the reported SNPs for psoriasis and PsA.

Supplementary Table S7. The effect estimates of the instrumental variables for psoriasis (exposure) and eBMD/Fracture.

Supplementary Table S8. The effect estimates of the instrumental variables for PsA (exposure) and eBMD/Fracture.

Supplementary Table S9. The effect estimates of the instrumental variables for eBMD (exposure) and psoriasis/PsA from UK biobank dataset.

Supplementary Table S10. Multinomial logistic regression between psoriasis/PsA (exposure) and Osteoporosis/Osteopenia (outcome).

Supplementary Table S11. The associations of genetic determined psoriasis/PsA with fracture risk by using different MR methods (two-sample).

Supplementary Table S12. The Mendelian Randomization results of psoriasis/PsA with eBMD using one SNP at HLA region.

Supplementary Table S13. The associations of genetic determined eBMD with psoriasis/PsA by using different MR methods.

Key messages:

What is already known about this subject?

Observational studies suggest that there is still debate on whether the psoriasis/PsA were risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture.

Using the drugs such as methotrexate, ciclosporin in the psoriatic patients can affect the process of bone remodeling.

Psoriatic arthritis patients sometimes accompany with pain, swelling and immobilization in one or more joints.

What does this study add?

The association between psoriatic arthritis and BMD/osteoporosis/fracture was not genetically determined but secondary (e.g., treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin).

Psoriasis without arthritis was not a risk factor for low BMD and osteoporosis.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Psoriatic arthritis patients should be screened for osteopenia and osteoporosis and proper management should be provided to reduce the fracture risk, especially for those who received treatment with methotrexate or ciclosporin.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UK Biobank database and the GEnetic Factors for OSteoporosis (GEFOS) Consortium. We also thank the Westlake University Supercomputer Center for the facility support and technical assistance.

Fundings

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871831) and by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (LR17H070001).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2016;2:16082. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandran V, Raychaudhuri SP. Geoepidemiology and environmental factors of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Journal of autoimmunity 2010;34(3):J314–J21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding X, Wang T, Shen Y, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis in China: a population-based study in six cities. European Journal of Dermatology 2012;22(5):663–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2005;52(1):23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin X, Low HQ, Wang L, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies multiple novel associations and ethnic heterogeneity of psoriasis susceptibility. Nature communications 2015;6:6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2013;133(2):377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenman M, Abraham S. Diagnosis and management of psoriatic arthropathy in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64(625):424–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nestle F, Kaplan D, Schon M. Barker J: Psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2009;361(17):496–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandrup F, Holm N, Grunnet N, et al. Psoriasis in monozygotic twins: variations in expression in individuals with identical genetic constitution. Acta dermato-venereologica 1982;62(3):229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elder JT, Nair RP, Guo S-W, et al. The genetics of psoriasis. Archives of dermatology 1994;130(2):216–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moll J, Wright V. Familial occurrence of psoriatic arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 1973;32(3):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsoi LC, Stuart PE, Tian C, et al. Large scale meta-analysis characterizes genetic architecture for common psoriasis associated variants. Nature communications 2017;8:15382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuart PE, Nair RP, Tsoi LC, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of psoriatic arthritis and cutaneous psoriasis reveals differences in their genetic architecture. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2015;97(6):816–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kathuria P, Gordon KB, Silverberg JI. Association of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with osteoporosis and pathological fractures. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2017;76(6):1045–53. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreiher J, Weitzman D, Cohen AD. Psoriasis and osteoporosis: a sex-specific association? Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2009;129(7):1643–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller J, Kang J-H, Lin H-C. Association between osteoporosis and psoriasis: results from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database in Taiwan. Osteoporosis International 2013;24(6):1835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocijan R, Englbrecht M, Haschka J, et al. Quantitative and qualitative changes of bone in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis patients. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2015;30(10):1775–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modalsli E, Åsvold B, Romundstad P, et al. Psoriasis, fracture risk and bone mineral density: the HUNT Study, Norway. British Journal of Dermatology 2017;176(5):1162–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busquets N, Vaquero CG, Moreno JR, et al. Bone mineral density status and frequency of osteoporosis and clinical fractures in 155 patients with psoriatic arthritis followed in a university hospital. Reumatologia clinica 2014;10(2):89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramot Y. Psoriasis and osteoporosis: the debate continues. British Journal of Dermatology 2017;176(5):1117–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenland S, Morgenstern H. Confounding in health research. Annual review of public health 2001;22(1):189–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Human molecular genetics 2014;23(R1):R89–R98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao PP, Xu LW, Sun T, et al. Relationship between alcohol use, blood pressure and hypertension: an association study and a Mendelian randomisation study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019;73(9):796–801. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Didelez V, Sheehan N. Mendelian randomization as an instrumental variable approach to causal inference. Statistical methods in medical research 2007;16(4):309–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng J, Frysz M, Kemp JP, et al. Use of Mendelian Randomization to examine causal inference in osteoporosis. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2019;10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li GH-Y, Cheung C-L, Au PC-M, et al. Positive effects of low LDL-C and statins on bone mineral density: an integrated epidemiological observation analysis and Mendelian randomization study. International Journal of Epidemiology 2019. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trajanoska K, Morris JA, Oei L, et al. Assessment of the genetic and clinical determinants of fracture risk: genome wide association and mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 2018;362:k3225. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bai WY, Zhu XW, Cong PK, et al. Genotype imputation and reference panel: a systematic evaluation on haplotype size and diversity. Brief Bioinform 2019. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai WY, Wang L, Ying ZM, et al. Identification of PIEZO1 polymorphisms for human bone mineral density. Bone 2020;133:115247. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS medicine 2015;12(3):e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris JA, Kemp JP, Youlten SE, et al. An atlas of genetic influences on osteoporosis in humans and mice. Nature genetics 2019;51(2):258–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Zheng C, Kim C, et al. Causal mediation analysis in the context of clinical research. Ann Transl Med 2016;4(21):425–25. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.11.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological methods 2010;15(4):309–34. doi: 10.1037/a0020761 [published Online First: 2010/10/20] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angrist JD, Imbens GW. Two-stage least squares estimation of average causal effects in models with variable treatment intensity. Journal of the American statistical Association 1995;90(430):431–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yavorska OO, Burgess S. MendelianRandomization: an R package for performing Mendelian randomization analyses using summarized data. International Journal of Epidemiology 2017;46(6):1734–39. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 2018;7:e34408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verbanck M, Chen C-Y, Neale B, et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nature genetics 2018;50(5):693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogdie A, Harter L, Shin D, et al. The risk of fracture among patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a population-based study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2017;76(5):882–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borman P, Babaoğlu S, Gur G, et al. Bone mineral density and bone turnover in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clinical rheumatology 2008;27(4):443–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lekamwasam S, Adachi JD, Agnusdei D, et al. A framework for the development of guidelines for the management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International 2012;23(9):2257–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wada C, Kataoka M, Seto H, et al. High-turnover osteoporosis is induced by cyclosporin A in rats. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism 2006;24(3):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu X, Zheng H. Factors influencing peak bone mass gain. Front Med 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0748-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedreira PG, Pinheiro MM, Szejnfeld VL. Bone mineral density and body composition in postmenopausal women with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy 2011;13(1):R16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haycock PC, Burgess S, Wade KH, et al. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: the design, analysis, and interpretation of Mendelian randomization studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2016;103(4):965–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng J, Baird D, Borges M-C, et al. Recent developments in Mendelian randomization studies. Current epidemiology reports 2017;4(4):330–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies NM, von Hinke Kessler Scholder S, Farbmacher H, et al. The many weak instruments problem and Mendelian randomization. Statistics in Medicine 2015;34(3):454–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harden JL, Krueger JG, Bowcock AM. The immunogenetics of psoriasis: a comprehensive review. Journal of autoimmunity 2015;64:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng HF, Zhang C, Sun LD, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism of MHC region is associated with subphenotypes of Psoriasis in Chinese population. J Dermatol Sci 2010;59(1):50–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.03.006 [published Online First: 2010/06/16] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng HF, Zuo XB, Lu WS, et al. Variants in MHC, LCE and IL12B have epistatic effects on psoriasis risk in Chinese population. J Dermatol Sci 2011;61(2):124–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.12.001 [published Online First: 2011/01/07] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and self-reported codes for psoriasis and PsA in UK Biobank.

Supplementary Table S2. The International Classification of Diseases(ICD) codes and self-reported codes for excluded diseases.

Supplementary Table S3. Characteristics of participants of psoriasis/controls in UK-Data-1.

Supplementary Table S4. Characteristics of participants of PsA/controls in UK-Data-1.

Supplementary Table S5. The characteristics of the studies for the summary-statistic data.

Supplementary Table S6. The proxy SNPs exhibited to replace the reported SNPs for psoriasis and PsA.

Supplementary Table S7. The effect estimates of the instrumental variables for psoriasis (exposure) and eBMD/Fracture.

Supplementary Table S8. The effect estimates of the instrumental variables for PsA (exposure) and eBMD/Fracture.

Supplementary Table S9. The effect estimates of the instrumental variables for eBMD (exposure) and psoriasis/PsA from UK biobank dataset.

Supplementary Table S10. Multinomial logistic regression between psoriasis/PsA (exposure) and Osteoporosis/Osteopenia (outcome).

Supplementary Table S11. The associations of genetic determined psoriasis/PsA with fracture risk by using different MR methods (two-sample).

Supplementary Table S12. The Mendelian Randomization results of psoriasis/PsA with eBMD using one SNP at HLA region.

Supplementary Table S13. The associations of genetic determined eBMD with psoriasis/PsA by using different MR methods.