Abstract

A new ternary chromium disulfide, Ba9Cr4S19, has been grown out of BaCl2 molten salt. Single-crystal structure analysis revealed that it crystallizes in the centrosymmetric space group C2/c with lattice parameters: a = 12.795(3) Å, b = 11.3269(2) Å, c = 23.2057(6) Å, β = 104.041(3)°, and Z = 4. Ba9Cr4S19 comprises four face-sharing Cr-centered octahedra with disulfide ions occupying sites on each terminal face. The resulting Cr4S15 tetramer units are isolated by nonmagnetic Ba-centered polyhedra in the ab plane and barium disulfide (=Ba4(S2)2) layers along the c-axis. Following the structure analysis, the title compound should be expressed as [Ba2+]9[Cr3+]4[(S2)2–]4[S2–]11, which is also consistent with Cr2p X-ray photoemission spectra showing trivalent states of the Cr atoms. The unique Cr-based zero-dimensional structure with the formation of these disulfide ions can be achieved for the first time in ternary chromium sulfides, which adopt 1–3 dimensional frameworks of Cr-centered polyhedra.

Introduction

Polysulfide compounds with S–S bonds or Sn2– (2 ≤ n) anions are of great interest because they can be used in a wide range of practical applications, for example, rechargeable alkali ion batteries,1 vulcanized rubber,2 and hydrodesulfurization catalysts.3 The fundamental chemistry underlying such applications is the facile ability of sulfides to form or break covalent S–S bonds in specific reaction environments. However, in contrast to a large number of reports on glasses, complexes, and organometallics with polysulfide anions,4−6 very few studies have been conducted on metal polychalcogenide solids because the low thermal stability of Sn2– fragments (typically lower than 500 °C) is incompatible with high-temperature solid-state reactions required to obtain solid-state phases.7

Molten salt (flux) synthesis is one of the most useful approaches to obtain new extended solid-state polysulfide compounds.7 Previous studies on polysulfide synthesis often used alkali-metal polysulfides with melting points much lower than 500 °C as flux, yielding novel polysulfides, mainly with d0 and d10 transition metal cations (e.g., Ti4+, Nb5+, Cu+, and Ag+)8−12 and main group metal cations (e.g., Te4+ and Sn2+).11,13 These polysulfides exhibit diverse low-dimensional frameworks in which the metal centers are anisotropically connected via bridging and/or chelating Sn2– ligands. The Sn2– fragments could be used as building blocks to design new low-dimensional magnetic/electrical materials. However, ternary or multinary polysulfide compounds with nonpaired electrons (i.e., d1–d9 metals) that show magnetism and electrical conductivity have not been sufficiently explored yet,14,15 probably because of the high thermodynamic stability of simple binary metal sulfides.

A chromium sulfide system prefers to take oxidation states of chromium between +2 and +4. Although there are two binary chromium disulfides, namely, amorphous and crystalline CrS3, ternary or multinary Cr-based polysulfides have never been reported. In the chromium sulfide system, ternary chromium sulfides have been the most extensively investigated because of their structural diversity.16−19 In particular, the Ba–Cr–S system is the only one that shows a dimensional reduction of a Cr-based structural framework from three-dimensional (3D) (tunnel-like) through two-dimensional (2D) (layers) to one-dimensional (1D) (chains) units when the ratio of Ba/Cr atoms is increased (see Figure 1).17,20,21 It should be noted that only high-pressure methods can access the infinite 1D chains of face-sharing CrS6 octahedra as observed in Ba3CrS5 and Ba3Cr2S6. In contrast, shorter octahedral chains are typically linked by other Cr-centered polyhedra to form a 3D framework.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the low-dimensional framework of Cr-centered polyhedra and the molar ratio of Ba/Cr.

This study reports the first ternary chromium disulfide Ba9Cr4S19, which could be obtained by a flux crystal growth method using BaCl2 molten salt. This new compound shows a unique zero-dimensional structure composed of Cr4S15 tetramer units thanks to the incorporation of disulfide ions.

Results and Discussion

A photograph of single crystals of Ba9Cr4S19 is shown in Figure 2. The single-crystal structure analysis revealed that Ba9Cr4S19 crystallizes in the space group C2/c (No. 15) with the following unit cell parameters: a = 12.795(3) Å, b = 11.3269(2) Å, c = 23.2057(6) Å, β = 104.041(3) Å, and Z = 4. The details of the structure refinement are listed in Table 1, atomic coordinates and atomic displacement parameters are given in Table 2, and anisotropic displacement parameters are listed in Table S1. Selected bond distances and angles are summarized in Table S2. Solid-state reactions using a stoichiometric mixture of BaS, Cr2S3, and S were performed in an attempt to synthesize polycrystalline powder samples. Varying the reaction temperature and time did not yield the target phase at all; instead, unidentified phases were obtained. This result suggests that BaCl2 flux is essential to obtain Ba9Cr4S19.

Figure 2.

Photograph of single crystals of Ba9Cr4S19 on a 1 mm grid-cell plate.

Table 1. Results of the Structure Refinement of Ba9Cr4S19 using Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction Data.

| formula | Ba9Cr4S19 |

| formula weight | 2053.11 |

| radiation | Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) |

| T (K) | 297 |

| crystal system | monoclinic |

| space group | C2/c (no. 15) |

| a (Å) | 12.7695(3) |

| b (Å) | 11.3269(2) |

| c (Å) | 23.2057(6) |

| β (°) | 104.041(3) |

| V (Å3) | 3256.16(13) |

| Z | 4 |

| Dcal (g/cm3) | 4.188 |

| F000 | 3616 |

| no. of measured reflections | 11 692 |

| no. of unique reflections | 3326 |

| no. of observed reflections (F2 > 2σ(F2)) | 2837 |

| Rint (%) | 2.89 |

| final R1/wR (F2 > 2σ(F2)) (%) | 2.57/4.31 |

| GoF | 1.035 |

| maximum/minimum residual peak (e/Å3) | 1.284/–1.093 |

Table 2. Crystallographic and Refinement Data Obtained from the Single-Crystal Structure Analysis of Ba9Cr4S19.

| atom | site | x | y | z | occp. | Ueq (102 × Å2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba1 | 8f | 0.77471(2) | 0.70539(3) | 0.69208(2) | 1 | 1.895(8) |

| Ba2 | 8f | 0.38371(3) | 0.67568(3) | 0.56529(2) | 1 | 2.190(9) |

| Ba3 | 8f | 0.13367(2) | 0.40518(3) | 0.49137(2) | 1 | 1.701(8) |

| Ba4 | 4e | 0 | 0.35485(3) | 3/4 | 1 | 1.162(9) |

| Ba5 | 8f | 0.42825(3) | 0.63735(3) | 0.37094(2) | 1 | 2.431(9) |

| Cr1 | 8f | 0.38585(6) | 0.52682(6) | 0.71416(3) | 1 | 0.936(17) |

| Cr2 | 8f | 0.17169(6) | 0.54902(6) | 0.64108(3) | 1 | 1.034(17) |

| S1 | 4e | 1/2 | 0.34973(14) | 3/4 | 1 | 1.21(4) |

| S2 | 8f | 0.54271(9) | 0.60900(10) | 0.68742(5) | 1 | 1.03(2) |

| S3 | 8f | 0.28613(9) | 0.70678(10) | 0.68009(5) | 1 | 1.33(3) |

| S4 | 8f | 0.22482(9) | 0.45936(10) | 0.73887(6) | 1 | 1.20(3) |

| S5 | 8f | 0.31206(10) | 0.43529(10) | 0.61594(5) | 1 | 1.24(3) |

| S6 | 8f | –0.00970(10) | 0.59023(11) | 0.65717(6) | 1 | 1.70(3) |

| S7 | 8f | 0.00784(10) | 0.43141(11) | 0.61379(6) | 1 | 1.67(3) |

| S8 | 8f | 0.12235(10) | 0.65598(10) | 0.54418(6) | 1 | 1.39(3) |

| S9 | 8f | 0.35172(17) | 0.33883(15) | 0.44804(9) | 1 | 5.47(6) |

| S10 | 8f | 0.4300(3) | 0.4728(3) | 0.48347(14) | 0.5 | 3.11(7) |

| S11 | 8f | 0.2824(2) | 0.5016(2) | 0.42524(14) | 0.5 | 2.76(7) |

Figure 3 shows the schematic view of the Ba9Cr4S19 crystal structure along the b-axis and [301] directions. The present compound possesses a Cr4S15 tetramer unit, half of which is an asymmetric unit because the middle point between two Cr1 atoms is positioned on a 2-fold axis (see Figure 4a). The four Cr-centered octahedra in the tetramer are linked by sharing the common S3 faces along the [301] direction. Two sulfur atoms, S6 and S7, bound to the Cr2 atom on each terminal face in the tetramer unit are coupled to each other at a bond distance of dS6–S7 = 2.0998(19) Å, in contrast to significantly longer distances between any other adjacent S–S bonds (∼3.5 Å) in the Cr1/Cr2 octahedra. This short bond distance strongly suggests a dimerization of S6 and S7 atoms into a disulfide ion (S2)2–. In fact, the intramolecular distance is consistent with those typically observed in disulfide compounds.22,23 Therefore, the terminal Cr2(S2)S4 octahedron is more distorted than the Cr1S6 octahedron, which is also rationalized by a comparison of their distortion indices: DCr1 = 0.01242 for Cr1S6 and DCr2 = 0.01648 for Cr2(S2)S4. Figure S1 shows the local coordination environment around Ba sites. These Ba atoms have 9- or 10-fold coordination for S atoms. In particular, Ba2, Ba3, and Ba5 are bound to disulfide ions (S9–S10, S9–S11, and S10–S11), which are described in detail below.

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of Ba9Cr4S19 viewed along the b-axis and [310] directions. Red bonds represent the dimerization of two sulfur atoms.

Figure 4.

(a) Fragment of the Cr4S15 tetramer unit. Displacement ellipsoids are shown at the 99% level. (b) Arrangement of disulfide ions in Ba4S4 layers on the ab plane. Half occupancy of S10 and S11 sites results in the formation of two independent disulfide ions, S9–S10 and S9–S11.

Each Cr4S15 tetramer unit is separated via nonmagnetic Ba atoms in the ab plane so as to form a two-dimensional slab with four CrS6 octahedral thickness, alternately stacked with a Ba4S4 (=Ba4(S2)2) layer along the c-axis. As shown in Figure 4b, the four sulfur atoms (S9 × 2, S10, and S11) in the Ba4S4 layers form two types of disulfide ions (S9–S10 and S9–S11) along the [110] direction. The intramolecular bond distance between S9 and S11 (=1.892(4) Å) is shorter than that between S10 and S11 (=2.058(3) Å) atoms. The nearest inter-dimer S–S distance corresponding to dS9–S9 = 4.433(3) Å is significantly long, indicating a very weak interaction between the ions.

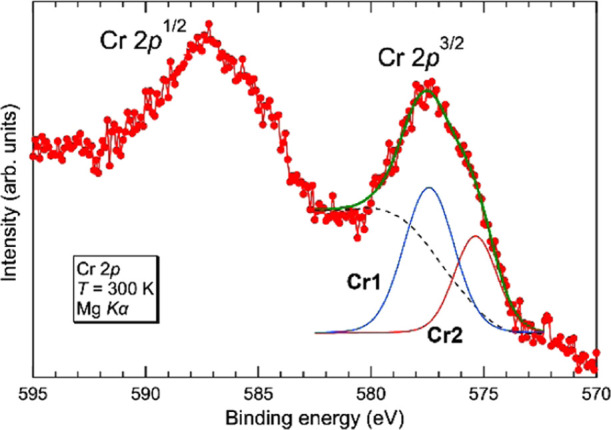

Considering the structure formed by disulfide ions, the chemical formula can be expressed as Ba9Cr4(S2)4S11. Based on the charge balance, all chromium cations in Ba9Cr4(S2)4S11 should be trivalent. The results of the bond valence sum (BVS) calculation are summarized in Table 3. The BVS values of Cr1 and Cr2 atoms are 2.83 and 2.946, respectively, which agree well with the expected ones. The BVS values of the S6, S7, S9, S10, and S11 atoms comprising disulfide ions are also consistent with the results of structural characterization. X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed to further investigate the oxidation states of these Cr ions. Figure 5 shows the Cr 2p XPS spectrum collected from single crystals of Ba9Cr4(S2)4S11. The Cr 2p3/2 spectrum is decomposed into two components with binding energies of 575.37 and 577.43 eV, which could be assigned to Cr3+ species. The component at the lower binding energy should be assigned to the Cr2 atom bonded to a disulfide ion with an overall charge of −2.24 The Cr1/Cr2 atomic ratio estimated from their spectral areas is 0.64:0.36, which roughly agrees with that obtained by structure analysis.

Table 3. Bond Valence Sum Values for Ba9Cr4S19.

| atom | BVS | atom | BVS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ba1 | 2.31 | S1 | –1.98 |

| Ba2 | 2.27 | S2 | –2.33 |

| Ba3 | 2.54 | S3 | –2.20 |

| Ba4 | 2.55 | S4 | –2.07 |

| Ba5 | 2.29 | S5 | –2.05 |

| Cr1 | 2.95 | S6 | –1.19 |

| Cr2 | 2.83 | S7 | –1.31 |

| S8 | –1.98 | ||

| S9 | –1.07 | ||

| S10 | –0.74 | ||

| S11 | –1.50 |

Figure 5.

Cr 2p core-level photoemission spectrum collected from Ba9Cr4S19 at 300 K. Blue and red lines represent the components derived from Cr1 and Cr2 sites, respectively. Bold green and dashed black lines represent the total fitting curve and the Shirley background, respectively.

Both Cr1 and Cr2 atoms in a six-fold coordination form nonequivalent bonds with the surrounding sulfur ligands at distances ranging from 2.35 to 2.50 Å. These Cr–S bond distances are consistent with those in related ternary chromium sulfides with trivalent Cr ions, such as Ba3Cr2S620 and CsCr5S8.16 The Cr1–Cr1 and Cr1–Cr2 bond distances in the tetramer unit are 2.9854(14) and 2.8579(10) Å, respectively. Based on Pauling’s third rule, a face-sharing octahedron is less stable than the corner- and edge-sharing ones because of the larger Coulomb repulsion between the neighboring cations in the former. The cation–cation distance between the ideal face-sharing octahedra can be described as 1.16 × dCr–S. Because the Cr-centered octahedra are distorted, the average bond distances of Cr1–(S1/S2/S2) and Cr1–(S3/S4/S5) were considered to roughly estimate the Cr–Cr distances expected from ideal face-sharing (Cr1)2S9 and (Cr1)(Cr2)S9 octahedra, respectively. As a result, the bond distances of 2.843 Å for Cr1–Cr1 and 2.771 Å for Cr1–Cr2 were obtained. The corresponding experimental values are 5.0 and 1.3% larger than the calculated values. This bond elongation possibly results from the reduction in Coulomb repulsion between the Cr atoms. However, its degree is not very large compared with those observed with 1D sulfides Ba3CrS5 and Ba3Cr2S6 with infinite 1D chains of face-sharing octahedra,20 in which the Cr–Cr bond distances are more than 10% longer than those expected from the ideal octahedra.

Dimensional reduction is widely observed in other multinary chalcogenides.25−27 For example, RE-Ga-S systems (RE: rare-earth metal) systematically decrease the dimensional framework composed of Ga-centered polyhedra from 2D to 0D with increasing the molar ratio of RE/Ga.25 In contrast, the zero dimensionality of Ba9Cr4S19 is not in line with the relationship between the low-dimensional framework and the molar ratio of Ba/Cr in the Ba–Cr–S system.21 The molar ratio of Ba/Cr for Ba9Cr4S19 is 2.25, which is within the regime for the 1D framework (Figure 1). It is likely that two types of the arrangement of disulfide ions play an important role in the crossover from 1D to 0D. In the first, two disulfide pairs are arranged in a 2D manner between the 2D slabs composed of Cr-based tetramer units. Such a low-dimensional arrangement of polysulfide ions interrupts direct linkage between the metal-centered polyhedra. Similar dimensional reduction induced by polysulfide ions is observed in di- or multinary (oxy-)polysulfide compounds (e.g., VS428 and Ba10S(VO3S)629). In the second type, disulfide ions occur on the terminal Cr-centered octahedra in the tetramer units, which would cause the breaking of 1D chains into smaller fragments. However, a disulfide ion does not always function as a ligand that reduces the dimensionality. For example, the amorphous chromium sulfide CrS3 (=Cr(S2)1.5) comprises 1D chains of trivalent Cr atoms surrounded by six sulfur atoms, all of which form disulfide ions.30 The three sulfur atoms are shared between each neighboring Cr atom in a chain and one of them is coupled with a sulfur atom from another chain, resulting in a complex 3D framework. Therefore, the existence of nonmagnetic Ba atoms, which break the linkages of Cr-centered octahedra, is essential for dimensional reduction.

At present, the low-dimensional magnetism of the Ba–Cr–S system has not been sufficiently investigated because it is difficult to obtain sufficient samples to measure physical properties.20,21 Based on the structure analysis, the Cr4S15 tetramer unit can be regarded as a spin tetramer with two types of nearest-neighbor interactions: J1 for Cr1–Cr2 and J2 for Cr1–Cr1. Figure 6 shows the temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility (χ = M/H) of Ba9Cr4S19 in a magnetic field of 10 kOe. The data were collected from several tiny single crystals, which were identified as the present phase by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD). No significant difference was observed between the zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) data. The χ(T) does not obey the Curie–Weiss law in the measured temperature range; instead, it monotonically decreases with the decrease of the temperature. The upturn observed below 40 K is probably due to impurity phases or defects in the lattice. A close inspection, however, detected a small kink at approximately 320 K, implying an antiferromagnetic ordering. Given the similar values of the Cr1–(Cr1/Cr2) bond angles (Table S3), both J1 and J2 are expected to be antiferromagnetic. In principle, the ideal spin tetramer model does not exhibit a long-range magnetic order regardless of the sign/magnitude of the intratetramer interactions.31 If Ba9Cr4S19 is magnetically ordered, additional terms such as interchain interactions and magnetic anisotropies should be taken into account to describe the magnetic behaviors. Higher-temperature data of χ(T), theoretical calculations, and neutron diffraction experiments would be needed in future research.

Figure 6.

Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility of Ba9Cr4S19, measured under zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and FC conditions. The inset shows an enlarged view of the high-temperature data.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the successful crystal growth of a new member of the Ba–Cr–S system, Ba9Cr4S19, from BaCl2 molten salt. The polysulfide ligands, which had never been formed in extended chromium sulfides, allowed access to the 0D framework of Cr-centered octahedra. The high-temperature flux method with non-sulfide molten salt shown in the present study opens up possibilities for obtaining novel low-D polysulfide magnets.

Experimental Section

Synthesis

Ba9Cr4S19 single crystals were obtained by a flux crystal growth method using BaCl2 molten salt. First, 0.875 mmol of BaS (High Purity Chemicals, 3N), 0.25 mmol of Cr2S3 (High Purity Chemicals, 3N), and 0.25 mmol of BaCl2 (Rare Metallics, 3N) were thoroughly mixed, pelletized, and then loaded into an alumina crucible and sealed in a silica tube under vacuum. These starting materials were then heated in a muffle furnace to 1050 °C for 6 h, held for 24 h, cooled to 750 °C for 60 h, and then cooled to room temperature by turning the furnace off. To remove the flux and green powdery byproduct, the product was repeatedly washed with distilled water by sonication. Black block single crystals were collected via vacuum filtration. The typical dimensions of the Ba9Cr4S19 single crystals were 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.05 mm3.

Characterization

Structure determination of the single crystals was performed by a Rigaku XtaLab mini II diffractometer (Mo Kα radiation). The structure was solved by a dual-space algorithm method (SHELXT)32 and refined by a full-matrix least-squares method with SHELXL,33 using an Olex2 graphical user interface.34 X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed using a Mg Kα X-ray source (JEOL, JPS-9010MC). The Fermi level was calibrated using the C 1s signal. The magnetic susceptibility measurements were conducted in a magnetic field (H) of 1 kOe under zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. 15H02024, 16H06438, 16H06441, 19H02594, 19H04711, 16H06439, and 20H05276) and a research grant from Innovative Science and Technology Initiative for Security, ATLA, Japan (No. JPJ004596).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c06017.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Grayfer E. D.; Pazhetnov E. M.; Kozlova M. N.; Artemkina S. B.; Fedorov V. E. Anionic Redox Chemistry in Polysulfide Electrode Materials for Rechargeable Batteries. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 4805–4811. 10.1002/cssc.201701709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura S.; Matsuo Y.; Okamatsu T.; Arita T.; Shimomura M.; Hirai Y. Low-Friction, Superhydrophobic, and Shape-Memory Vulcanized Rubber Microspiked Structures. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1901226 10.1002/adem.201901226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bej S. K.; Maity S. K.; Turaga U. T. Search for an Efficient 4,6-DMDBT Hydrodesulfurization Catalyst: A Review of Recent Studies. Energy Fuels 2004, 18, 1227–1237. 10.1021/ef030179+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Draganjac M.; Rauchfuss T. B. Transition Metal Polysulfides: Coordination Compounds with Purely Inorganic Chelate Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1985, 24, 742–757. 10.1002/anie.198507421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Manthiram A. Highly Reversible Room-Temperature Sulfur/Long-Chain Sodium Polysulfide Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1943–1947. 10.1021/jz500848x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steudel R.; Chivers T. The Role of Polysulfide Dianions and Radical Anions in the Chemical, Physical and Biological Sciences, Including Sulfur-Based Batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3279–3319. 10.1039/C8CS00826D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatzidis M. G. Molten Alkali-Metal Polychalcogenides as Reagents and Solvents for the Synthesis of New Chalcogenide Materials. Chem. Mater. 1990, 2, 353–363. 10.1021/cm00010a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunshine S. A.; Kang D.; Ibers J. A. A New Low-Temperature Route to Metal Polychalcogenides: Solid-State Synthesis of K4Ti3S14, a Novel One-Dimensional Compound. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 6202–6204. 10.1021/ja00254a060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burschka C. Kristallstruktur von NH4CuS4/The Crystal Structure of NH4CuS4. Z. Naturforsch., B 1980, 35, 1511–1513. 10.1515/znb-1980-1204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch W.; Dürichen P. Preparation and Crystal Structure of the New Ternary Niobium Polysulfide K4Nb2S14 Exhibiting the Dimeric Complex Anion [Nb2S14]4-. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1997, 261, 103–107. 10.1016/S0020-1693(97)05456-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen S. L.; Jang J. I.; Ketterson J. B.; Kanatzidis M. G. (Ag2TeS3)2·A2S6 (A = Rb, Cs): Layers of Silver Thiotellurite Intergrown with Alkali-Metal Polysulfides. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 9098–9100. 10.1021/ic1011346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Kanatzidis M. G. AMTeS3(A = K, Rb, Cs; M = Cu, Ag): A New Class of Compounds Based on a New Polychalcogenide Anion, TeS32-. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 1890–1898. 10.1021/ja00084a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J. H.; Varotsis C.; Kanatzidis M. G. Syntheses, Structures, and Properties of Six Novel Alkali Metal Tin Sulfides: K2Sn2S8, α-Rb2Sn2S8, β-Rb2Sn2S8, K2Sn2S5, Cs2Sn2S6, and Cs2SnS14. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 2453–2462. 10.1021/ic00063a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi H.; Gray D.; Qiang Huang F.; Ibers J. A. Structures and Bonding in K0.91U1.79S6 and KU2Se6. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 3307–3311. 10.1021/ic052140l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stüble P.; Kägi J. P.; Röhr C. Synthesis, Crystal and Electronic Structure of the New Sodium Chain Sulfido Cobaltates(II), Na3CoS3 and Na5[CoS2]2(Br). Z. Naturforsch., B 2016, 71, 1177–1189. 10.1515/znb-2016-0179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huster J. Darstellung Und Kristallstruktur Der Alkalithiochromate (III), ACr5S8 (A = Cs, Rb Und K). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1978, 447, 89–96. 10.1002/zaac.19784470108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petricek S.; Boller H.; Klepp K. A Study of the Cation Order in Hollandite-like MxT5S8 Phases☆. Solid State Ionics 1995, 81, 183–188. 10.1016/0167-2738(95)00182-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rouxel J.; Moëlo Y.; Lafond A.; DiSalvo F. J.; Meerschaut A.; Roesky R. Role of Vacancies in Misfit Layered Compounds: The Case of the Gadolinium Chromium Sulfide Compound. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 3358–3363. 10.1021/ic00093a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes O.; Zheng C.; Check C. E.; Zhang J.; Chacon G. Synthesis and Structural Analysis of BaCrS2. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 1889–1893. 10.1021/ic980609p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka H.; Miyaki Y.; Yamanaka S. High-Pressure Synthesis and Structures of Novel Chromium Sulfides, Ba3CrS5 and Ba3Cr2S6 with One-Dimensional Chain Structures. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 176, 206–212. 10.1016/S0022-4596(03)00398-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka H.; Miyaki Y.; Yamanaka S. High-Pressure Synthesis and Structures of New Barium Chromium Sulfides, BaCr4S7 and Ba2Cr5S10, with New Type Face-Sharing CrS6 Structure Units. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 80, 2170–2176. 10.1246/bcsj.80.2170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher P. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of the Dirubidiumpentachalcogenides Rb2S5 and Rb2Se5. Z. Kristallogr. - Cryst. Mater. 1979, 150, 1–4. 10.1524/zkri.1979.150.14.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tegman R. The Crystal Structure of Sodium Tetrasulphide, Na2S4. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 1973, 29, 1463–1469. 10.1107/S0567740873004735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xi K.; He D.; Harris C.; Wang Y.; Lai C.; Li H.; Coxon P. R.; Ding S.; Wang C.; Kumar R. V. Enhanced Sulfur Transformation by Multifunctional FeS2/FeS/S Composites for High-Volumetric Capacity Cathodes in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Adv Sci 2019, 6, 1800815 10.1002/advs.201800815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.; Shen J.; Zhu W.-W.; Liu Y.; Wu X.-T.; Zhu Q.; Wu L. Two New Phases in the Ternary RE–Ga–S Systems with the Unique Interlinkage of GaS 4 Building Units: Synthesis, Structure, and Properties. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 13731–13738. 10.1039/C7DT02545A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.; Shen J. N.; Shi Y. F.; Li L. H.; Chen L. Quaternary Rare-Earth Selenides with Closed Cavities: Cs[RE9Mn4Se18] (RE = Ho-Lu). Inorg. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 298–305. 10.1039/C4QI00202D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Y.; Liu P. F.; Lin H.; Wu L. M.; Wu X. T.; Zhu Q. L. Quaternary Semiconductor Ba8Zn4Ga2S15 Featuring Unique One-Dimensional Chains and Exhibiting Desirable Yellow Emission. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 7942–7945. 10.1039/C9CC02575H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmann R.; Baumann I.; Kutoglu A.; Rösch H.; Hellner E. Die Kristallstruktur Des Patronits V(S2)2. Naturwissenschaften 1964, 51, 263–264. 10.1007/BF00638454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoud S.; Mentré O.; Kabbour H. The Ba10S(VO3S)6 Oxysulfide: One-Dimensional Structure and Mixed Anion Chemical Bonding. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 1349–1357. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibble S. J.; Walton R. I.; Pickup D. M. Local Structures of the Amorphous Chromium Sulfide, CrS3, and Selenide, CrSe3, from X-Ray Absorption Studies. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1996, 11, 2245–2251. 10.1039/dt9960002245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner J. C.; Kobayashi H.; Tsujikawa I.; Nakamura Y.; Friedberg S. A. Theoretical Studies on the Isolated Spin Cluster Complex, Tetrameric Cobalt (II) Acetylacetonate Co4(C5H7O2)8: Effects of Competing Superexchange Interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1975, 63, 19–34. 10.1063/1.431043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT - Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov O. V.; Blake A. J.; Champness N. R.; Schröder M. OLEX: New Software for Visualization and Analysis of Extended Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 1283–1284. 10.1107/S0021889803015267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.