Abstract

Bedaquiline (TMC-207) is a key anti-tubercular drug to fight against multidrug resistance tuberculosis. Little information is available till date on the impact of any disease state toward its pharmacokinetic behavior. The present research work aimed to investigate the effect of renal impairment and diabetes mellitus on the oral pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline in the rat model. Renal impairment and diabetes mellitus were induced in the Wistar rat model separately using cisplatin and streptozotocin, respectively, and thereafter, an oral pharmacokinetic study of bedaquiline was carried out in the individual disease models as well as in the normal rat model. Pharmacokinetic parameters of bedaquiline were not altered markedly in cisplatin-induced renal-impaired rats compared to normal rats except an area under the curve (AUC) for plasma concentration of bedaquiline in the experimental time frame (AUC0–t) reduced to 3477 ± 228 from 4984 ± 1174 ng h/mL, respectively. Maximum plasma concentrations of bedaquiline (259 ± 77 ng/mL), AUC0–t (3112 ± 1046 ng h/mL), and AUC0–∞ (3673 ± 1493 ng h/mL) were significantly reduced along with an increase in the clearance of bedaquiline (3.1 ± 1.1 L/h/kg) in the case of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats compared to respective pharmacokinetic parameters of bedaquiline (482 ± 170 ng/mL, 4984 ± 1174 ng h/mL, and 6137 ± 1542 ng h/mL) in the normal rats. Preclinical findings suggest that dose adjustment of bedaquiline is required in the diabetes mellitus condition to prevent the therapeutic failure of bedaquiline treatment, but clinical exploration is needed to establish the fact. It is the first report for the consequence of renal impairment and diabetes mellitus on the pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline in the preclinical model.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the leading causes of death globally.1 The emergence of resistance in the form of multiple drug resistance (MDR) and extensive drug resistance (XDR) to the currently used anti-TB drugs poses a threat to the healthcare professionals in the whole world towards the development of new anti-TB drugs.2,3 Bedaquiline (TMC-207) is one such new anti-TB drug introduced in the market after a gap of four decades. It acts against TB by a novel mechanism of mycobacterial ATP synthase inhibition by blocking the mycobacterium proton pump.4,5 It has been given fast-track accelerated approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) for its use in the treatment of MDR-TB.6 It is also included in the “List of Essential Medicines” by the World Health Organization (WHO).7

Bedaquiline is available as a salt form of fumaric acid and given orally as a tablet dosage form under the brand name of “SIRTURO”. The available strength is 100 mg per tablet. The recommended dose of bedaquiline for a total duration of 24 weeks therapy is 400 mg once daily for the first two weeks and, thereafter, 200 mg orally three times per week (with at least 48 h between doses) for another 22 weeks.8 Upon oral administration, it is principally subjected to oxidative metabolism via cytochrome P450 isoenzymes 3A4 (CYP3A4), leading to the formation of the N-monodesmethyl metabolite, which has 5-fold less antimycobacterial potency as compared to bedaquiline.9 Recent clinical trials on the use of bedaquiline have revealed that it is associated with major side effects such as QT prolongation (a measure of the time between the Q and T wave of electrocardiogram), phospholipidosis, hepatitis, bilateral hearing impairment, joint pain, hemoptysis, and diarrhoea.10 The incidence of mortality in TB is increasing day by day due to co-morbidities, like diabetes. Diabetes exacerbates the clinical course of TB, and conversely, TB deteriorates glycemic control.11 Similarly, there is ample evidence where renal impairment can lead to worsening of the patient conditions leading to elevated mortality levels.12 Generally, impairment in the renal function leads to reduced clearance of a drug (primarily eliminated by the kidney) that elevates the exposure of the drug and thereafter aggravates the incidence of dose-dependent side-effects.13 Moreover, diabetic patients are prone to renal impairment.14 In this direction, it is well known that a drop or rise in plasma concentration of the drug may lead to therapeutic failure and growing resistance for antibiotics or enhance dose-dependent adverse effects, respectively.15−18

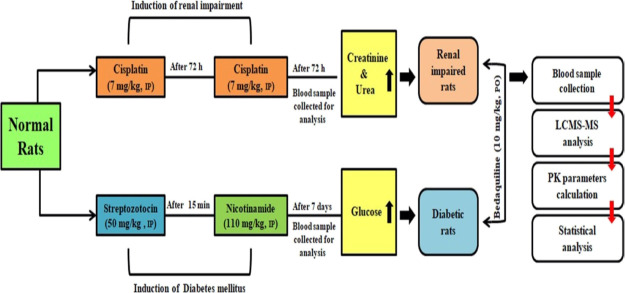

Under these circumstances, it is imperative to investigate any alteration in the pharmacokinetic behavior of bedaquiline under different disease states. In this direction, a preclinical investigation is always useful before going into a pricey and risky clinical examination. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report for such a recently approved drug like bedaquiline on its pharmacokinetic behavior in the preclinical model of renal impairment and diabetes mellitus. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to induce renal impairment and diabetes mellitus separately in the rats followed by comparative oral pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline in rats under these disease states and normal rats (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of work plan for the present research work.

2. Results

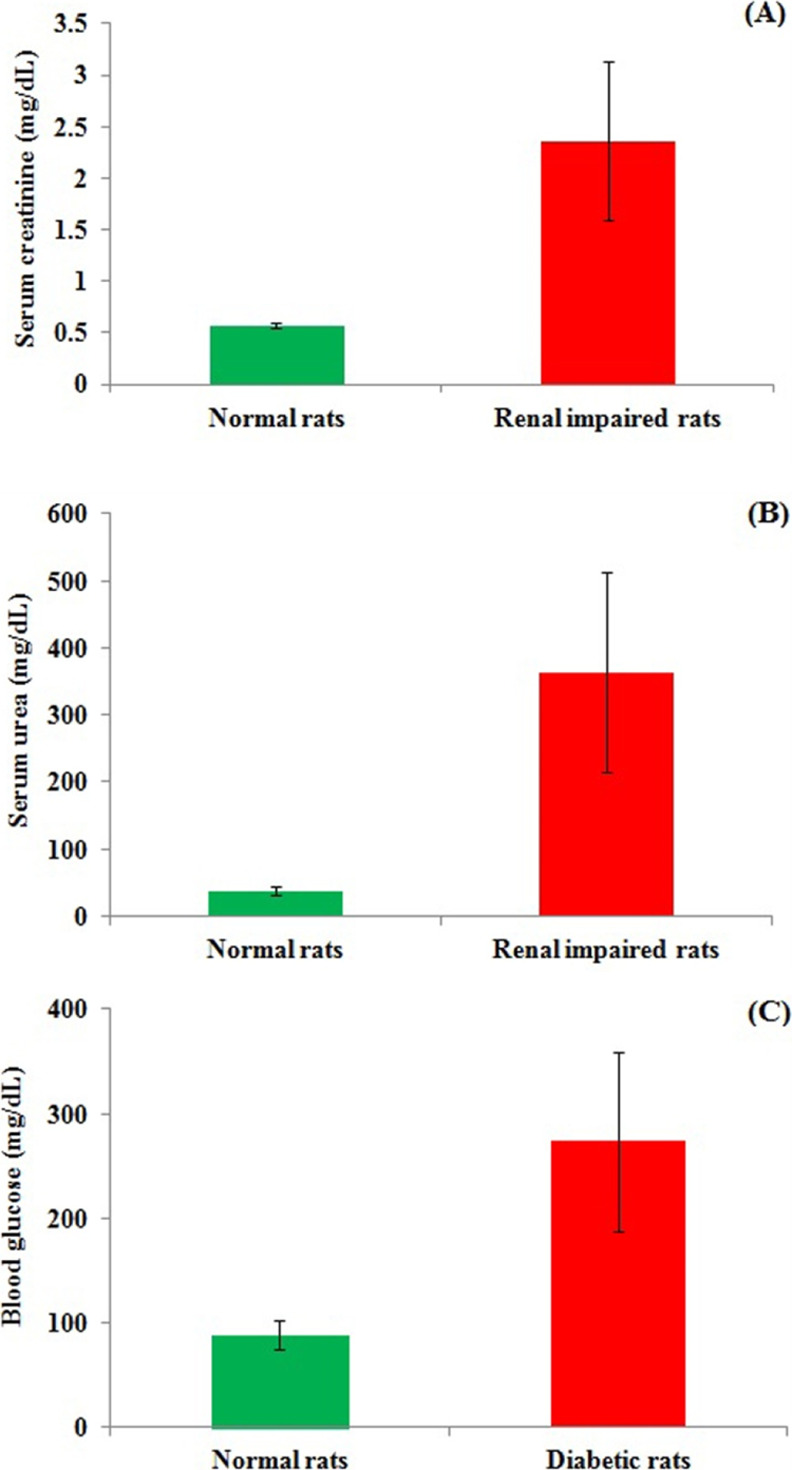

Pharmacokinetic study of bedaquiline was carried out in normal rats, renal-impaired rats, and diabetic rats after single-dose administration through the oral route. Cisplatin was used to induce renal impairment where mean serum creatinine and urea levels of the selected 10 rats for the pharmacokinetic study were found to be enhanced by 4.1 times and 9.6 times as compared to normal rats, respectively (Figure 2). Streptozotocin was used in rats to induce diabetes, where fasting blood glucose level in the selected 10 diabetic rats for the pharmacokinetic study was found to be enhanced by 3.1 times as compared to normal rats (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Main biochemical parameters of the rats for carrying out oral pharmacokinetic studies of bedaquiline: (A) serum creatinine level of normal rats and renal-impaired rats; (B) serum urea level of normal rats and renal-impaired rats; (C) blood glucose level of normal rats and diabetic rats. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 10). Data were compared between normal rats vs renal impaired rats or normal rats vs diabetic rats. Data were found to be statistically significant (***) at the p < 0.001 level.

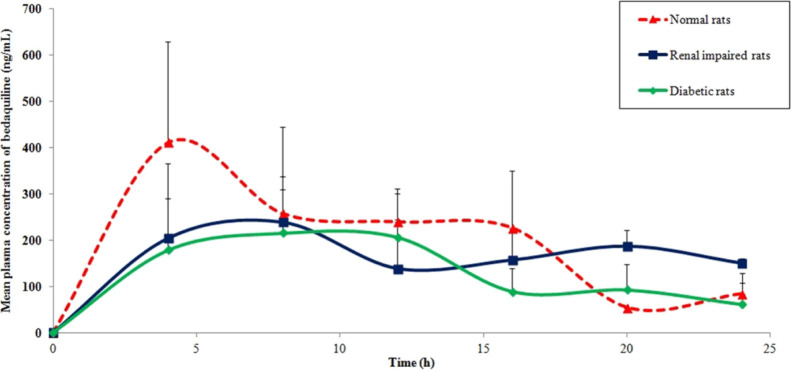

Bedaquiline was administered orally to normal rats, and the mean plasma concentration of bedaquiline versus time profile is depicted in Figure 3. Typical selected reaction monitoring (SRM) chromatograms for bedaquiline and internal standard (IS) are shown in Figure 4. The calculated pharmacokinetic parameters for bedaquiline are represented in Table 1. The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of bedaquiline was found to be 482 ± 170 ng/mL. The time to attain Cmax (Tmax) was 7.2 ± 5.2 h, which is in line with the reported value for humans.8 Values of the area under the curve (AUC) were in the range of 5–6 μg h/mL after an oral dose of 10 mg/kg. The elimination half-life (T1/2) value was found to be 10.3 ± 4.4 h in rats. The volume of distribution (Vd/F) and clearance (Cl/F) of bedaquiline after oral administration were 26 ± 13 L/kg and 1.7 ± 0.4 L/h/kg, respectively. This is the first time report for oral pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline in any preclinical model where all the important pharmacokinetic parameters are described based on a detailed investigation for 24 h.19

Figure 3.

Mean plasma concentration vs time profile of bedaquiline after its oral administration at 10 mg/kg in normal rats, renal-impaired rats, and diabetic rats. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5).

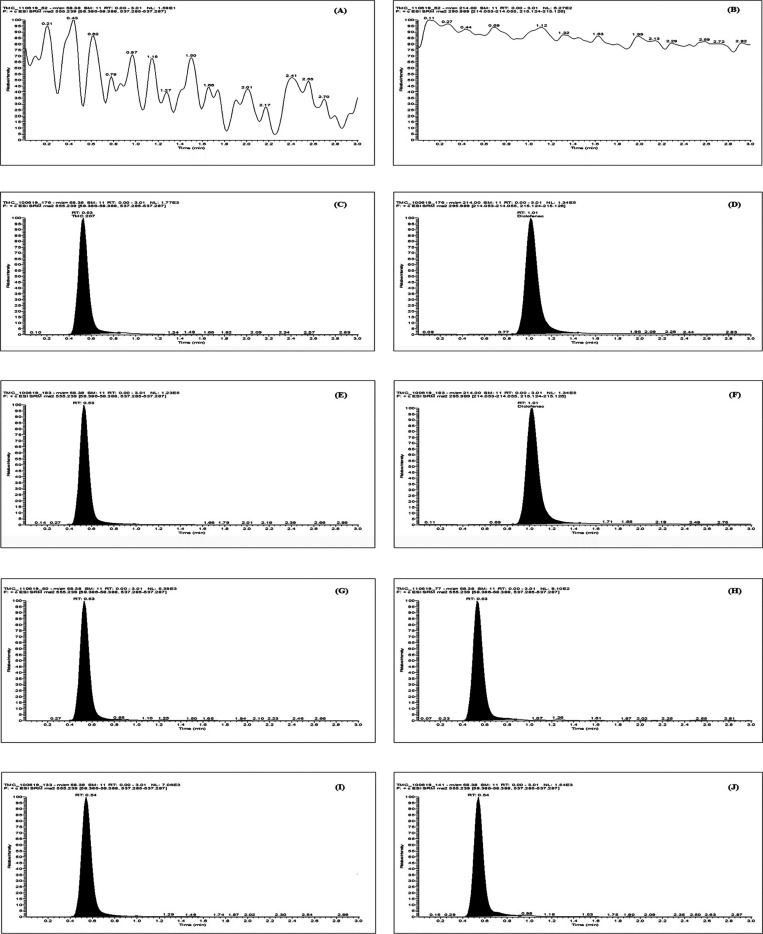

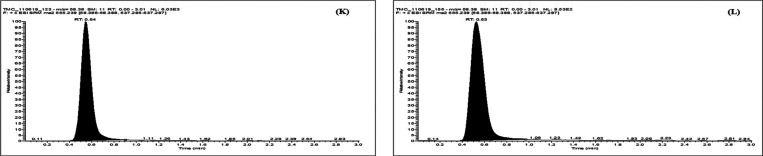

Figure 4.

Representative SRM chromatograms with transition pairs of m/z 555.2 > 58.4 and m/z 295.9 > 214.0 for blank plasma sample (A,B), plasma sample spiked at LLOQ of bedaquiline with IS (C,D), plasma sample spiked at ULOQ with IS (E,F), bedaquiline level at 8 and 24 h in the pharmacokinetic study sample of normal rats (G,H), bedaquiline level at 8 and 24 h in the pharmacokinetic study sample of renal-impaired rats (I,J), and bedaquiline level at 8 and 24 h in the pharmacokinetic study sample of diabetic rats (K,L).

Table 1. Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Bedaquiline after Its Oral Administration at 10 mg/kg in Normal, Renal-Impaired, and Diabetic Ratsa.

| pharmacokinetic parameter | normal rats | renal-impaired rats | diabetic rats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 482 ± 170 | 341 ± 91 | 259 ± 77* |

| Tmax (h) | 7.2 ± 5.2 | 7.2 ± 3.3 | 9.6 ± 2.2 |

| AUC0–24 (ng h/mL) | 4984 ± 1174 | 3477 ± 228* | 3112 ± 1046* |

| AUC0–∞ (ng h/mL) | 6137 ± 1542 | 5247 ± 901 | 3673 ± 1493* |

| T1/2 (h) | 10.3 ± 4.4 | 8.3 ± 3.7 | 6.3 ± 2.9 |

| Vd/F (L/kg) | 26 ± 13 | 24 ± 9 | 26 ± 15 |

| Cl/F (L/h/kg) | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 1.1* |

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5); data were compared between normal rats vs renal impaired rats and normal rats vs diabetic rats; data were evaluated for statistical significance (*) at p < 0.05 level.

To explore the effect of renal impairment on oral pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline, cisplatin was used to treat normal rats to induce renal impairment as mentioned above and used for further experimentation. When bedaquiline was administered orally to renal-impaired rats, Cmax (341 ± 91 ng/mL) decreased as compared to normal rats by 29%, which lacks statistical significance. Though oral exposure under the experimental time frame (AUC0–24: 3477 ± 228 ng h/mL) was significantly dropped by 30%, oral exposure considered beyond the experimental time frame was found to recover like normal rats (p value > 0.05, statistically insignificant) based on the calculated AUC0–∞ value (5247 ± 901 ng h/mL). There was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of bedaquiline at each time point in normal rats versus renal impaired rats except at 20 h (p < 0.05). T1/2 of bedaquiline in renal-impaired rats declined to 8.3 ± 3.7 h in comparison to 10.3 ± 4.4 h in normal rats, but the difference is not statistically significant. Other pharmacokinetic parameters of bedaquiline like Tmax, Vd/F, and Cl/F remained unaltered as values are found to be similar for both the renal-impaired rats and normal rats.

To explore the effect of diabetes mellitus on oral pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline, streptozotocin was injected into normal rats to induce the above-mentioned disease condition and used for further experimentation. Upon oral administration of bedaquiline in diabetic rats, Cmax (259 ± 77 ng/mL) reduced markedly as compared to normal rats. Moreover, oral exposure based on AUC0–24: 3112 ± 1046 ng h/mL and AUC0–∞: 3673 ± 1493 ng h/mL also considerably declined by 38–40% in comparison to normal rats. There was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of bedaquiline at each time point in normal rats versus diabetic rats. Though T1/2 (6.3 ± 2.9 h) of bedaquiline decreased in the present disease condition of diabetes mellitus in rats, the difference with normal circumstances lacks statistical significance. However, noteworthy enhancement on the clearance of bedaquiline (3.1 ± 1.1 L/h/kg) by 1.8 fold was observed in the diabetic rats as compared to normal rats. The diabetes mellitus condition showed an insignificant effect on the other pharmacokinetic parameters of bedaquiline like Tmax and Vd/F as these did not vary from normal rats.

3. Discussion

Pharmacokinetic parameters of bedaquiline were not altered significantly in the renal-impaired rats except AUC0–24h. Bedaquiline has high plasma protein binding (∼99.9%).8 Any changes in the unbound fraction of a drug in plasma protein binding may influence the pharmacokinetic profile of the drug. It has been evident from the literature that impaired renal function is associated with altered binding of drugs to plasma protein. This is due to displacement from binding sites of drugs by various endogenous substances that circulate in blood during renal disease. The reduced level of plasma protein during renal impairment also influences the plasma protein binding of drugs.20,21 These factors possibly contribute toward the reduced exposure of bedaquiline as a result of an increased fraction of unbound drugs. A similar result was found for aprepitant, a neurokinin NK1-receptor antagonist, and rosiglitazone, an antidiabetic drug, where oral pharmacokinetic exposure was decreased to 36 and 19%, respectively, in renal-impaired patients.22,23 It is reported that urinary excretion of unchanged bedaquiline was less than 0.001% at its 400 mg dose in clinical studies.8 The present results of bedaquiline pharmacokinetics in the renal-impaired model may be correlated to the reported observations as renal clearance of the unchanged drug was found to be insignificant there.

Based on the results for the pharmacokinetic profile of bedaquiline in the diabetic animal model, diabetes is found to be a major risk factor for the treatment of TB. Cmax and/or AUC of anti-TB drugs, namely pyrazinamide, isoniazid, and rifampicin, were noticeably reduced in diabetic conditions.24−26 The elevated level of xanthine oxidase (an enzyme responsible for the metabolism of pyrazinamide) in plasma and hepatic levels was correlated to the event of pyrazinamide. On the other hand, similar evidence is also reported for other drugs that are not in the category of anti-TB: Cmax and AUC of simvastatin and its hydrosalt simvastatin acid were reduced by 72 and 56%, respectively, in the diabetic rat model. This was due to enhanced metabolism, which is linked to higher CYP3A activity and more hepatic uptake of the drug.27 Brunner et al. demonstrated that AUC of cyclosporine was significantly reduced by 1.47 fold with increased clearance in diabetic rats as compared to nondiabetic rats.28 Shu et al. reported similar results for significantly reduced plasma exposure of atorvastatin in the diabetic rats by 4.5-fold because of upregulation of CYP3A4 activity and OATP1B1 transporters.29 Gawroñska-Szklarz et al. reported that AUC and Vd of lidocaine significantly decreased along with marked enhancement in the clearance of lidocaine in animals with experimental diabetes due to augmented enzymatic activity.30 Though enhancement in enzyme activity was found to be the major reason for the increased possibility of therapeutic failure in most of the circumstances, there may be other reasons like in the case of phenytoin where a significant increase in glycosylation of plasma proteins under diabetic conditions might increase the unbound fraction of the drug that ultimately leads to its reduce exposure in plasma.31 In contrast to the above fact of reduced oral exposure of drugs in diabetic conditions, there is a report where plasma exposure of verapamil was increased by 3.8 folds in diabetes.32

Overall, diabetes is found to be a crucial risk factor for bedaquiline treatment in TB that may produce a slower response to TB treatment or worsen the treatment outcomes.33 Moreover, there may be enhanced risk of QT prolongation by bedaquiline if a CYP3A4 inhibitor like bromocriptine (recommended adjunct therapy for glycemic control) is used for diabetic patients under antidiabetic drugs like sulfonylureas therapy.34 Dosage adjustment may be required for anti-TB oral therapy with bedaquiline in diabetic conditions. The present findings are based on the pharmacokinetic study after single dose oral administration. Additionally, variation in concentration data should be minimized using more number of animals at each time point so that statistical evaluation can be performed in a better way. Further investigation should be focused on alteration in the pharmacokinetic behavior of bedaquiline upon its prolonged exposure using higher number of animals. Finally, clinical exploration is needed to establish the fact.

4. Conclusions

In the quest to explore the effect of renal impairment and diabetes mellitus on the oral pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline, we investigated the same using normal rats, cisplatin-induced renal-impaired rats, and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats as there is no such precedent in any preclinical model. Therefore, this is the first report on the detailed pharmacokinetic profile of bedaquiline in any preclinical model. Oral exposure of bedaquiline was found to be only significantly affected by renal impairment, but it is less likely to cause any alteration in the dosing schedule of bedaquiline, whereas dose adjustment of bedaquiline is necessary in diabetic conditions to restrict therapeutic failure, which subsequently aid to the growing concern of resistance. Nevertheless, a clinical investigation is required to ascertain the fact of dose adjustment in oral therapy before going into the fathom of this idea.

5. Material and Methods

5.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Bedaquiline (purity ≥ 98%) was obtained from the Medicinal Chemistry Division of our institute. Diclofenac sodium (purity ≥ 98%), streptozotocin (purity ≥ 95%), nicotinamide, (purity ≥ 98%), and cisplatin (certified reference material grade) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. Acetonitrile and formic acid of liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) grade were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. All other materials used like, methanol, and sodium-carboxymethyl cellulose were of analytical grade. Ultrapure water was used for all experiments (Direct-Q3, Water Purification System, Merck Millipore).

5.2. Animal Husbandry, Maintenance, and Ethical Prerequisites

Pharmacokinetic studies were carried out using healthy adult female Wistar rats (6–8 weeks of age) that were domiciled in polypropylene cages under standard laboratory conditions like a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 50 ± 20%, light/dark cycle of 12/12 h, fed with standard pellet diet for rats, and free access to water. Animal feed was procured from M/s Ashirwad Industries (Chandigarh, India), and its composition is provided in Table S1 (Supporting Information). Animals were obtained from our institutional animal house facility and maintained there as well. Animal experimentations were carried out as per the “Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals” (CPCSEA) guidelines (Government of India, New Delhi). Necessary approval was obtained from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of our institute (IAEC approval no: 74/155/2/2019) before the commencement of pharmacokinetic studies in rats.

5.3. Dose Selection and Dose Formulation

Single-dose pharmacokinetic studies of bedaquiline were performed using normal rats, renal-impaired rats, and diabetic rats. Bedaquiline is available in the market as a tablet dosage form with 100 mg of bedaquiline in each tablet. We converted this human dose of bedaquiline to a rat dose using the following formula

where km = correction factor, human dose = 100 mg, human body weight = 60 kg, human km = 37, and rat km = 6. Therefore, the rat dose of bedaquiline was calculated to 10.28 mg/kg, and we performed all pharmacokinetic studies in rats at the bedaquiline dose level of 10 mg/kg. We planned to use the rat dose based on the available tablet strength irrespective of the daily maximum dose due to the following reasons: (a) dose of bedaquiline is changed after first 2 weeks of treatment in normal circumstances as recommended for MDR-TB treatment; (b) there is no report available on detailed pharmacokinetics as well as dose-dependent pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline in the preclinical model; and (c) it is difficult to predict beforehand the pharmacokinetic behavior of bedaquiline in the disease states. Preclinical dose formulation of bedaquiline was prepared freshly as an aqueous suspension containing 0.5% (w/v) sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. The dose–volume was fixed at 10 mL/kg. Animals were fasted for 10 h before the start of the experimentation with water ad libitum.

5.4. Induction of Disease Conditions: Renal Impairment and Diabetes Mellitus

Renal impairment was induced in 15 rats by the treatment of cisplatin. Normal saline was used as a vehicle for the dose preparation of cisplatin. Cisplatin was injected at 7 mg/kg through the intraperitoneal route followed by a second dose of cisplatin after 72 h.35 After a waiting period of 72 h, a blood sample was obtained from overnight fasted animals to perform renal function tests using the serum. The elevated levels of creatinine and urea in cisplatin-induced rats at a highly significant level as compared to normal rats confirmed the occurrence of renal impairment in rats.35,36 These biochemical parameters were estimated using an automated clinical chemistry analyzer (model: EM360; make: Erba Mannheim).

Diabetes mellitus was induced in 15 rats by the treatment of streptozotocin. Sodium citrate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) and normal saline were used as a vehicle for dose preparation of streptozotocin and nicotinamide, respectively. Streptozotocin was injected at 50 mg/kg through the intraperitoneal route followed by a dose of nicotinamide (110 mg/kg) after 15 min through the same route.29 After a waiting period of seven days, a blood sample was obtained from overnight fasted animals to measure fasting glucose levels using a glucometer (model: Accu-Chek; make: Roche). The glucose level above 11.5 mM (>200 mg/dL) was considered as a successful occurrence of diabetes mellitus.29,37

5.5. Pharmacokinetic Study Design

To assess the effect of each disease state on pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline, pharmacokinetic studies were carried out after oral administration of bedaquiline in the following groups: group-1: normal rats, group-2: renal-impaired rats, and group-3: diabetic rats. Each group comprised of two subgroups for sparse sampling containing five animals each.15,38 Here, it should be mentioned that animals were confirmed for induction of each disease condition using the above-mentioned parameters, and then, only 10 rats were included for each disease state in the present investigation. After oral dosing of bedaquiline at a single-dose of 10 mg/kg, blood samples (∼25 μL each) were obtained from retro-orbital plexus into tubes containing an anticoagulant (aqueous ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution, 5% w/v) at 0 (predose), 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 h. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 10,643g for 10 min to get only 10 μL of plasma, which was further kept at −80 °C till analysis.

5.6. Sample Processing and Bioanalysis by LC–MS/MS

The stock solution of bedaquiline and Diclofenac (IS) was prepared in acetonitrile and water, respectively. Further dilutions were carried out by acetonitrile to make the standard solutions. A ten-point matrix match calibration curve for bedaquiline was prepared by spiking serially diluted standard solutions into blank plasma. Plasma samples (10 μL each) were processed by the addition of IS (2 μL of 100 μg/mL) followed by 188 μL of the solvent mixture containing acetonitrile: methanol (84:16, v/v) for plasma protein precipitation.16 Then, samples were vortex mixed for 2 min and centrifuged at 18,626g for 10 min. The organic layer was separated and transferred to the vial for analysis by LC–tandem MS (LC–MS/MS).

The triple quadrupole LC–MS/MS system (model: TSQ Endura; make: Thermo Scientific) was employed for the estimation of bedaquiline in plasma samples.16 The major metabolite of bedaquiline is N-monodesmethyl bedaquiline which was not quantified in the present study because of its cost and nonavailability to us. The measured concentration obtained from LC–MS/MS was multiplied by the factor of 20 to estimate the final concentration per mL of plasma. The optimized LC conditions and MS parameters are represented in Tables S2 and S3 (Supporting Information).

5.7. Pharmacokinetic Data Analysis

The plasma concentration profile of bedaquiline with respective time points was obtained from the measured concentration data and calculated further for different pharmacokinetic parameters by a noncompartmental method using PK solution software (Summit Research Services, USA).

5.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using online Student’s t-test (QuickCalcs, GraphPad Prism) to compare the pharmacokinetic parameters of bedaquiline in normal rats versus renal-impaired rats or normal rats versus diabetic rats. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

A.G. and A.D. are thankful to DST and UGC (New Delhi, India), respectively, for providing research fellowship support. Authors are grateful to Dr. Parvinder Pal Singh and Dr. Gurdarshan Singh to provide the necessary support to execute this research work. Institutional publication number: CSIR-IIIM/IPR/00230.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c06165.

Composition of diet for rats, LC conditions for plasma analysis of bedaquiline and MS parameters for plasma analysis of bedaquiline (PDF)

Author Contributions

A.G. and A.D. contributed equally to this work. A.G. and A.D. performed in vivo pharmacokinetics and MS preparation; S.S. performed compound isolation, purification, and characterization; PW performed all LC–MS/MS analysis; UN performed the overall study plan, execution, and MS preparation.

This research was supported by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (New Delhi, India) with internal research grant MLP6006 and Science and Engineering Research Board, Department of Science and Technology (New Delhi, India) with grant number (CSIR-IIIM) GAP-2181.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zaman K. Tuberculosis: a global health problem. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2010, 28, 111–113. 10.3329/jhpn.v28i2.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter N. D.; Strong M.; Belknap R.; Ordway D. J.; Daley C. L.; Chan E. D. Translating basic science insight into public health action for multidrug-and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Respirology 2012, 17, 772–791. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magotra A.; Sharma A.; Singh S.; Ojha P. K.; Kumar S.; Bokolia N.; Wazir P.; Sharma S.; Khan I. A.; Singh P. P.; Vishwakarma R. A.; Singh G.; Nandi U. Physicochemical, pharmacokinetic, efficacy and toxicity profiling of a potential nitrofuranyl methyl piperazine derivative IIIM-MCD-211 for oral tuberculosis therapy via in-silico–in-vitro–in-vivo approach. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 151–160. 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan M.; Xavier A. S. Bedaquiline—The first ATP synthase inhibitor against multi drug resistant tuberculosis. J. Young Pharm. 2013, 5, 112–115. 10.1016/j.jyp.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Mehra R.; Sharma S.; Bokolia N. P.; Raina D.; Nargotra A.; Singh P. P.; Khan I. A. Screening of antitubercular compound library identifies novel ATP synthase inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2018, 108, 56–63. 10.1016/j.tube.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R. Bedaquiline: first FDA-approved tuberculosis drug in 40 years. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2013, 3, 1–2. 10.4103/2229-516x.112228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines: Report of the WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 2019 (Including the 21st WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 7th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children), 2019.

- Van Heeswijk R. P. G.; Dannemann B.; Hoetelmans R. M. W. Bedaquiline: a review of human pharmacokinetics and drug–drug interactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 2310–2318. 10.1093/jac/dku171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson E.; Dosne A. G.; Karlsson M. Population pharmacokinetics of bedaquiline and metabolite M2 in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: the effect of time-varying weight and albumin. CPT: Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2016, 5, 682–691. 10.1002/psp4.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley K.; MbChB R. R.; Houston C.. A Trial of the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Bedaquiline and Delamanid, Alone and in Combination, among Participants Taking Multidrug Treatment for Drug-Resistant Pulmonary Tuberculosis; ACTG, 2018; pp 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson C. R.; Forouhi N. G.; Roglic G.; Williams B. G.; Lauer J. A.; Dye C.; Unwin N. Diabetes and tuberculosis: the impact of the diabetes epidemic on tuberculosis incidence. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 234. 10.1186/1471-2458-7-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K.-C.; Liao K.-F.; Lin C.-L.; Liu C.-S.; Lai S.-W. Chronic kidney disease correlates with increased risk of pulmonary tuberculosis before initiating renal replacement therapy: A cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine 2018, 97, e12550 10.1097/md.0000000000012550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnebjerg H.; Kothare P. A.; Park S.; Mace K.; Reddy S.; Mitchell M.; Lins R. Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of exenatide. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 64, 317–327. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afkarian M.; Sachs M. C.; Kestenbaum B.; Hirsch I. B.; Tuttle K. R.; Himmelfarb J.; De Boer I. H. Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 302–308. 10.1681/asn.2012070718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra A.; Bhatt S.; Magotra A.; Sharma A.; Kotwal P.; Gour A.; Wazir P.; Singh G.; Nandi U. Intervention of curcumin on oral pharmacokinetics of daclatasvir in rat: A possible risk for long-term use. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1967–1974. 10.1002/ptr.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal P.; Magotra A.; Dogra A.; Sharma S.; Gour A.; Bhatt S.; Wazir P.; Singh P. P.; Singh G.; Nandi U. Assessment of preclinical drug interactions of bedaquiline by a highly sensitive LC-ESI-MS/MS based bioanalytical method. J. Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2019, 1112, 48–55. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A.; Gour A.; Bhatt S.; Rath S. K.; Malik T. A.; Dogra A.; Sangwan P. L.; Koul S.; Abdullah S. T.; Singh G.; Nandi U. Effect of IS01957, a para-coumaric acid derivative on pharmacokinetic modulation of diclofenac through oral route for augmented efficacy. Drug Dev. Res. 2019, 80, 948–957. 10.1002/ddr.21574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padrini R. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with renal failure. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 44, 1–12. 10.1007/s13318-018-0501-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal P.; Dogra A.; Sharma A.; Bhatt S.; Gour A.; Sharma S.; Wazir P.; Singh P. P.; Kumar A.; Nandi U. Effect of natural phenolics on pharmacokinetic modulation of bedaquiline in rat to assess the likelihood of potential food-drug interaction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1257–1265. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindup W.; Henderson S.; Barker C.. Plasma Binding of Drug and Its Consequence; Belpaire F., Bogaert M., Tillement J. P., Verbeeck E., Eds.; Academic Press: Ghent, 1991; pp 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeeck R. K.; Musuamba F. T. Pharmacokinetics and dosage adjustment in patients with renal dysfunction. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 757–773. 10.1007/s00228-009-0678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman A. J.; Marbury T.; Fosbinder T.; Swan S.; Hickey L.; Bradstreet T. E.; Busillo J.; Petty K. J.; Viswanathan Aiyer K.-J.; Constanzer M.; Huskey S.-E. W.; Majumdar A. Effect of impaired renal function and haemodialysis on the pharmacokinetics of aprepitant. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2005, 44, 637–647. 10.2165/00003088-200544060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapelsky M. C.; Thompson-Culkin K.; Miller A. K.; Sack M.; Blum R.; Freed M. I. Pharmacokinetics of rosiglitazone in patients with varying degrees of renal insufficiency. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 43, 252–259. 10.1177/0091270002250602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijland H. M. J.; Ruslami R.; Stalenhoef J. E.; Nelwan E. J.; Alisjahbana B.; Nelwan R. H. H.; Van Der Ven A. J. A. M.; Danusantoso H.; Aarnoutse R. E.; Van Crevel R. Exposure to rifampicin is strongly reduced in patients with tuberculosis and type 2 diabetes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 848–854. 10.1086/507543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarisi O.; Mave V.; Gaikwad S.; Sahasrabudhe T.; Ramachandran G.; Kumar H.; Gupte N.; Kulkarni V.; Deshmukh S.; Atre S.; Raskar S.; Lokhande R.; Barthwal M.; Kakrani A.; Chon S.; Gupta A.; Golub J. E.; Dooley K. E. Effect of diabetes mellitus on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tuberculosis treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01383 10.1128/aac.01383-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemanth Kumar A. K.; Kannan T.; Chandrasekaran V.; Sudha V.; Vijayakumar A.; Ramesh K.; Lavanya J.; Swaminathan S.; Ramachandran G. Pharmacokinetics of thrice-weekly rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide in adult tuberculosis patients in India. Int. J. Tubercul. Lung Dis. 2016, 20, 1236–1241. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D.; Li F.; Zhang M.; Zhang J.; Liu C.; Hu M.-y.; Zhong Z.-y.; Jia L.-l.; Wang D.-w.; Wu J.; Liu L.; Liu X.-d. Decreased exposure of simvastatin and simvastatin acid in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 1215–1225. 10.1038/aps.2014.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner L. J.; Iyer L. V.; Vadiei K.; Weaver W. V.; Luke D. R. Cyclosporine pharmacokinetics and effect in the type I diabetic rat model. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 1989, 14, 287–292. 10.1007/bf03190113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu N.; Hu M.; Liu C.; Zhang M.; Ling Z.; Zhang J.; Xu P.; Zhong Z.; Chen Y.; Liu L.; Liu X. Decreased exposure of atorvastatin in diabetic rats partly due to induction of hepatic Cyp3a and Oatp2. Xenobiotica 2016, 46, 875–881. 10.3109/00498254.2016.1141437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawroñska-Szklarz B.; Musial D.; Pawlik A.; Paprota B. Effect of experimental diabetes on pharmacokinetic parameters of lidocaine and MEGX in rats. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 619–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp S. F.; Kearns G. L.; Turley C. P. Alteration of phenytoin binding by glycosylation of albumin in IDDM. Diabetes 1987, 36, 505–509. 10.2337/diabetes.36.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N.; Xie S.; Liu L.; Wang X.; Pan X.; Chen G.; Zhang L.; Liu H.; Liu X.; Liu X.; Xie L.; Wang G. Opposite effect of diabetes mellitus induced by streptozotocin on oral and intravenous pharmacokinetics of verapamil in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011, 39, 419–425. 10.1124/dmd.110.035642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur A.; Harries A. D. The double burden of diabetes and tuberculosis—Public health implications. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 101, 10–19. 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.; Zheng C.; Gao F. Use of bedaquiline and delamanid in diabetes patients: clinical and pharmacological considerations. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 3983. 10.2147/dddt.s121630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purena R.; Seth R.; Bhatt R. Protective role of Emblica officinalis hydro-ethanolic leaf extract in cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity in Rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 270–277. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkharfy K. M.; Ali F. A.; Alkharfy M. A.; Jan B. L.; Raish M.; Alqahtani S.; Ahmad A. Effect of compromised liver function and acute kidney injury on the pharmacokinetics of thymoquinone in a rat model. Xenobiotica 2020, 50, 858–862. 10.1080/00498254.2020.1745319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P.; Nandi U.; Pal T. K. Development of safety profile evaluating pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and toxicity of a combination of pioglitazone and olmesartan medoxomil in Wistar albino rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 62, 7–15. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra A.; Gour A.; Bhatt S.; Sharma P.; Sharma A.; Kotwal P.; Wazir P.; Mishra P.; Singh G.; Nandi U. Effect of rutin on pharmacokinetic modulation of diclofenac in rats. Xenobiotica 2020, 50, 1332–1340. 10.1080/00498254.2020.1773008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.