Abstract

Bidirectional cell-cell communication involving exosome-borne cargo such as miRNA, has emerged as a critical mechanism for wound healing. Unlike other shedding vesicles, exosomes selectively package miRNA by SUMOylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteinA2B1 (hnRNPA2B1). In this work, we elucidate the significance of exosome in keratinocyte-macrophage crosstalk following injury. Keratinocyte-derived exosomes were genetically labeled with GFP reporter (Exoκ-GFP) using tissue nanotransfection and were isolated from dorsal murine skin and wound-edge tissue by affinity selection using magnetic beads. Surface N-glycans of Exoκ-GFP were also characterized. Unlike skin exosome, wound-edge Exoκ-GFP demonstrated characteristic N-glycan ions with abundance of low base pair RNA and were selectively engulfed by wound-macrophages (ωmϕ) in granulation tissue. In vitro addition of wound-edge Exoκ-GFP to proinflammatory ωmϕ resulted in conversion to a proresolution phenotype. To selectively inhibit miRNA packaging within Exoκ-GFP in vivo, pH-responsive keratinocyte-targeted siRNA-hnRNPA2B1 functionalized lipid nanoparticles (TLNPκ) were designed with 94.3% encapsulation efficiency. Application of TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 to murine dorsal wound-edge significantly inhibited expression of hnRNPA2B1 by 80% in epidermis compared to TLNPκ/si-control group. Although no significant difference in wound closure or re-epithelialization was observed, TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treated group showed significant increase in ωmϕ displaying proinflammatory markers in the granulation tissue at day 10 post-wounding compared to TLNPκ/si-control group. Furthermore, TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treated mice showed impaired barrier function with diminished expression of epithelial junctional proteins, lending credence to the notion that unresolved inflammation results in leaky skin. This work provides insight wherein Exoκ-GFP are recognized as a major contributor that regulates macrophage trafficking and epithelial barrier properties post-injury.

Keywords: exosome, tissue nanotransfection, keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles, macrophage, wound healing

The dynamic cellular events following cutaneous injury rely on bidirectional cell-cell communication for efficient wound healing. Such crosstalk is traditionally known to occur via paracrine effects.1, 2 A recent paradigm has emerged wherein the predominant mechanism of cellular communication is attributable to extracellular vesicles (EV).3–7 These EV have distinct structural and biochemical properties depending on their intracellular site of origin that affects their biological function.8 A majority of these vesicles having diameters ranging from 50–1000 nm originate from the plasma membrane and are often referred to as microvesicles, ectosomes, microparticles, and exovesicles.8 Exosomes are a major class of EV (typically 30–150 nm in diameter) of endocytic origin released by all cell types following fusion of multi-vesicular bodies (MVB) with the plasma membrane.9, 10 Exosomes carry a distinctive repertoire of cargo such as miRNAs.11 RNA profiling of exosomes showed differences in miRNA abundance compared to the parent cells, suggesting that parent cells possess a sorting mechanism that guides specific intracellular miRNAs to enter into the exosomes.12–14 SUMOylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2B1 (hnRNPA2B1) has been implicated as a predominant mechanism of miRNA packaging within exosomes.15 Within the cell, miRNAs have specific sequence motifs that control their localization into exosomes. Binding of hnRNPA2B1 to the miRNA by recognition of these motifs controls their loading into exosomes. Moreover, SUMOylation of hnRNPA2B1 regulates the binding of hnRNPA2B1 to miRNAs. Given the presence of such a well-coordinated sorting mechanism, it is apparent that cell-cell crosstalk via exosomes is an active process. Such process is distinct from cellular communication mediated via shedding of other membrane vesicles that also carry biomolecules such as miRNA as cargo that is not selectively packaged in these vesicles. Lack of efficient isolation techniques of exosomes from other membrane vesicles of similar size have led to conclusions that are primarily derived from a heterogenous EV pool. This lack of discrimination among various membrane vesicles dampens the potential significance of exosomes in cellular communication and has impaired discovery of the role of exosome of specific cellular origins in communication.

The putative role of keratinocytes in wound healing and inflammation is well documented.16–19 At the wound site, cells of myeloid origin such as monocytes and macrophages are primarily responsible for mounting an early inflammatory response to injury.20–23 Both robust mounting of inflammation as well as timely resolution are key to successful tissue repair. The role of keratinocytes for the resolution of inflammation remains unclear and debated. This study rests on our observation that at the site of injury, EV of keratinocyte origin are critical for conversion of the myeloid cells into fibroblast-like cells in the granulation tissue.19 The objectives of this work were to isolate exosomes of keratinocyte origin at the wound-edge and to delineate their significance in the resolution of inflammation at the wound site. This work shows that keratinocyte derived exosomes carry miRNAs that direct resolution of macrophage numbers and function within the granulation tissue and are critical for functional wound closure.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification and isolation of keratinocyte-derived exosomes in murine skin.

To circumvent the EV complexity found in vivo in complex tissues, we employed an in vitro system and isolated exosomes from the heterogenous pool of EV derived from cultured keratinocytes. According to EVPedia24 and Exocarta,25 the three tetraspanins CD9, CD63 and CD81 are reliable markers of exosomes.26 In the interest of rigor, we employed a two-step process to isolate pure exosome. First, EV were isolated from keratinocyte-conditioned media using differential ultracentrifugation (Figure S1A). Second, the heterogenous EV were incubated with superparamagnetic Dynabeads™ conjugated with antibodies for CD9, CD63 and CD81 (Figure S1A). From the heterogenous EV mixture, only the tetraspanins expressing exosomes were trapped leaving the membrane particles and apoptotic bodies in the flow through. We tested all the nine criteria set forward by EV-track for transparent reporting (Figure S1). The size and concentration of the exosomes were analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NanoSight™) and Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure S1B–C). The density of the isolated exosomes was found to be 1.16g/ml. The isolated exosomes showed abundance of other reported exosome markers such as Alix, TSG101, HSP90 and Flotilin 1 (Figure S1D). The purity of the isolation was tested by immunoblotting of GM130 and Prohibitin that are reported as major contaminants of exosome preparation by EV-track.27 Additional quantitative analysis such as flow cytometry of these Dynabeads™ post-adsorption with exosomes following incubation with phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated TSG101 (TSG101-PE) antibody showed an increased shift in fluorescence intensity (Figure S1E). Furthermore, binding of PE tagged TSG101 antibody was tested by fluorescence anisotropy (Figure S1F) and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (Figure S1G). Binding of TSG101-PE by the resuspended isolated exosomes hindered their free rotation as shown by a marked increase in fluorescence anisotropy (Figure S1F). TSG101-PE had fast and unhindered diffusion when resuspended in PBS or in the presence of EV flow through. However, in the presence of exosomes, diffusion of TSG101-PE slowed down as shown by shifted autocorrelation curve (Figure S1G). These data validated that the two-step isolation process was successful in separating exosomes from the heterogenous EV pool. This method of exosome isolation was reported in EV-track (EV190103) with a preliminary EV-METRIC of 100%.28

The approach described above was applied for isolation of exosomes in vivo. Recent reports have highlighted the role of exosome in cutaneous wound healing.29, 30 Analysis of EV concentration from murine skin and day 5 wound-edge tissue (< 2mm from wound-edge) showed significant increase in EV as well as exosomes in day 5 wound-edge tissue (Figure 1A). Quantitative analysis revealed that exosome represents only about 10% of the total EV pools. In addition to the resident cells such as keratinocytes and fibroblasts, day 5 wound-edge tissue contains infiltrated blood-borne cells including macrophages. Thus, to understand whether the increase abundance of exosome at the wound-edge is due to increased release of exosomes by additional biogenesis in resident cells or contributed by infiltrating cells, it becomes critical to segregate the exosomes based on their cellular origin.

Figure 1. Isolation and characterization of keratinocyte-derived exosomes from murine skin.

(A) Quantification of extracellular vesicles and exosomes from murine skin and day 5 wound-edge tissue of C57BL/6 mice. (n=11, 12) (B) Schematic diagram of keratin 14 (K14) promoter-driven recombinant plasmids encoding CD9, CD63 or CD81 with “in frame” GFP reporter. (C) Representative scanning electron microscopic images of tissue nanotransfection (TNT) chip 2.0. (D) Schematic diagram showing the delivery of the three K14 promoter-driven plasmids via TNT in the dorsal murine skin. (E) Confocal microscopic images showing presence of keratinocyte derived exosome (Exoκ-GFP) in dermis (left) and super-resolution confocal microscopic images showing GFP labelled exosome (right). The white dash line shows epidermal-dermal junction. Scale, 10μm and 2μm. (F) Schematic diagram showing exosome isolation process from murine skin tissue post-TNT with the three plasmids. MP: membrane particles; AB: apoptotic bodies. (G) Particle size distribution of keratinocyte-derived exosomes (Exoκ−GFP), non-keratinocyte-derived exosomes (Exonon-GFP), and flow through (membrane particles and apoptotic bodies) from murine skin. (n=10) (H) Representative Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of murine keratinocyte-derived exosomes. Scale, 100 nm. (I-J) Binding of TSG-101 PE with the murine keratinocyte-derived exosome was further tested by autocorrelation curves as determined by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) (I) and time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy (J). (n=10) (K) Flow cytometric analysis of murine skin keratinocyte-derived exosome on GFP-trap magnetic beads showing binding of TSG-101 PE, Alix-FITC, Flotillin 1-PE and HSP90-FITC antibodies. The histograms demonstrate the shift in fluorescence after binding of murine Exoκ-GFP on the GFP-trap magnetic beads with the respective antibody. All data were shown as mean ± SEM. Data in A were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Data in J were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the post-hoc Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

Our previous work has recognized the critical role of keratinocytes derived EV in the conversion of injury-site myeloid cells to fibroblast-like cells in granulation tissue.19 However the significance of exosomes in such keratinocyte-myeloid cell crosstalk remains unknown. Since one or more of the three tetraspanins CD9, CD63 and CD81 are expressed in all exosomes, we designed three murine keratin 14 (K14) promoter-driven plasmids that encode for CD9, CD63 and CD81 with “in frame” GFP reporter (Figure 1B). Such promoter-driven plasmids allow expression of GFP tagged CD markers only in keratinocytes. The specificity of the plasmid cocktail was tested in murine keratinocytes, fibroblasts and ωmϕ (Figure S2A–C). We tested the hypothesis that in vivo topical delivery of these three plasmids would result in the expression of GFP in all exosomes that are of keratinocyte origin. We have previously reported that cutaneous delivery of reprogramming molecules via tissue nanotransfection (TNT) was efficient and effective in directly reprogramming dermal fibroblast cells into a variety of functionally distinct lineages.31 We have now generated a modified TNT silicon chip (TNT2.0) with longer needle height of 170μm and pore diameter of 4μm (Figure 1C). Modifying the electrical potential applied between the cargo within the chip and skin led to stepwise increases in the depth of transfection of fluorescein amidite (FAM)-labeled DNA (Figure 1D, Figure S2D) in wild type C57BL/6 mice. Delivery of these three K14 promoter-driven plasmids via TNT followed by super-resolution confocal microscopy demonstrated presence of exosome with GFP reporter expression in epidermis as well as in dermis (Figure 1E, Figure S2E). Because the GFP reporter protein was cloned in frame with the CD9, CD63 and CD81, pull down of GFP using magnetic traps is expected to isolate the Exoκ-GFP. Keratinocyte-derived exosomes were isolated from the tissue homogenate using GFP-magnetic traps followed by separating the exosomes from the beads using elution buffer (Figure 1F). The resultant flow through was further ultracentrifuged and the non-keratinocyte derived exosome (Exonon-GFP) were isolated using pan-CD superparamagnetic beads (Figure 1F). The size and concentration of Exoκ-GFP, Exonon-GFP and flow through were further examined using nanoparticle tracking analysis (Nanosight™) (Figure 1G). Scanning electron microscopy of Exoκ-GFP revealed presence of exosomes of different size (Figure 1H). Adsorption of Exoκ-GFP on GFP-Trap was tested by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (Figure 1I) and fluorescence anisotropy (Figure 1J). Flow cytometric analysis of GFP-trap beads post-adsorption with Exoκ-GFP following incubation with fluorescently tagged antibodies of exosome marker such as TSG101-PE, Alix-FITC, Flotilin1-PE and HSP90-FITC showed an increase in fluorescence intensity (Figure 1K). These findings demonstrate that the GFP-trap approach was successful in isolating Exoκ-GFP from murine tissue homogenate.

Ultracentrifugation is widely held as a gold standard for exosome isolation. In the interest of rigor, Exoκ-GFP was subjected to direct comparison with exosomes isolated using differential ultracentrifugation. Murine keratinocytes were transfected with the three K14 promoter-driven plasmids to label the exosomes with GFP-reporter. Exosomes were isolated from the cell culture supernatant using GFP-Trap and compared with exosomes isolated using ultracentrifugation (Figure 2A). No difference in size, shape and binding property were observed between the exosomes isolated using the two methodologies (Figure 2B–F).

Figure 2: Comparative analysis of keratinocyte-derived exosome with exosome isolated from cell culture conditioned media.

(A) Schematic diagram showing exosome isolation process from murine keratinocyte (Kera308) cultured media with and without transfection with keratin 14 promoter-driven recombinant plasmids encoding CD9, CD63 or CD81 with “in frame” GFP reporter. (B) The particle size distribution of exosomes and eluent (membrane particles and apoptotic bodies) from murine keratinocyte cultured media. (n=6) (C) Representative Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images of exosomes isolated using GFP beads and CD-beads. Scale, 200 nm (D) Flow cytometric analysis of murine keratinocyte-derived exosome on CD magnetic beads (CD63, CD9 and CD81) and GFP-beads showing binding of TSG-101 PE antibody. (E-F) Binding of TSG-101 PE with the murine keratinocyte-derived exosome was further tested by autocorrelation curves as determined by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) (E) and time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy (F) (n=20). All data were shown as mean ± SEM. Data in F were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the post-hoc Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

Characterization of keratinocyte-derived exosomes isolated from murine skin and wound-edge tissue.

Isolation of Exoκ-GFP from wild type mice showed a significant increase in day 5 wound-edge Exoκ-GFP compared to skin (Figure 3A). High-resolution automated electrophoresis of RNA isolated from Exoκ-GFP showed abundance of small bp RNA (<100 bp) in day 5 wound-edge tissue (Figure 3B). These data suggest Exoκ-borne miRNA signals are dispatched from resident keratinocytes of the wound-edge tissue to enable crosstalk with visiting immune cells.

Figure 3. Characterization of keratinocyte-derived exosome from murine skin and wound-edge tissue.

(A) Murine dorsal skin was transfected with keratin 14 promoter-driven recombinant plasmids encoding CD9, CD63 or CD81 with “in frame” GFP reporter via TNT. The keratinocyte-derived exosomes were isolated from skin and day 5 wound-edge tissue using GFP magnetic trap and quantified using NTA. Data shown as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. (n=8) (B) High-resolution automated electrophoresis of RNA isolated from skin and wound-edge Exoκ-GFP. RNA in wound-edge Exoκ-GFP was significantly abundant compared to that of skin Exoκ-GFP.

N-glycans molecule facilitate the uptake of keratinocyte-derived exosomes by macrophage at the wound-edge.

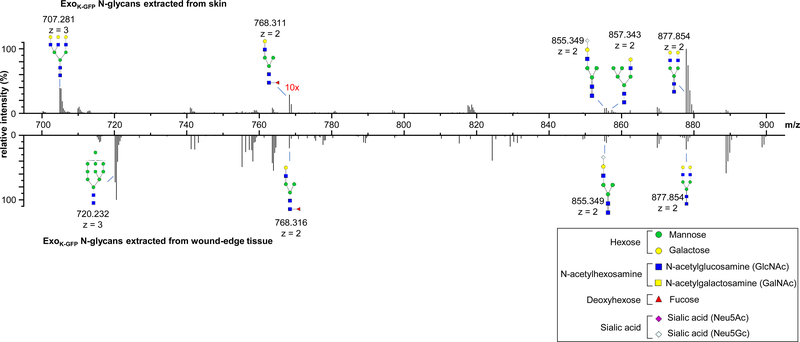

Based on our previous work that demonstrated the critical role of EVs of keratinocyte origin in the conversion of injury-site myeloid cells to fibroblast-like cells of granulation tissue,19 it is plausible that the exosomes released from the keratinocytes are likely engulfed by the ωmϕ. Immunohistochemistry followed by super-resolution confocal microscopic images revealed that unlike the skin adjacent to wound, the Exoκ-GFP at the wound-edge were selectively engulfed by the ωmϕ (Figure S3A–C). Macrophage has abundant membrane-bound C-type lectin receptors that share a common carbohydrate recognition domain.32 Such receptors are critical for binding to specific carbohydrate structures of endogenous self-molecules.33 The C-type lectin receptors on a macrophage membrane are able to bind branched sugars with terminal mannose, fucose, or N-acetyl-glucosamine, and mediate both endocytosis and phagocytosis.34 Intrigued by the site specific selective uptake of Exoκ-GFP by the ωmϕ, we tested the hypothesis that at the wound-edge, the Exoκ-GFP surface is selectively modified to facilitate uptake by the immune cells. Exoκ-GFP N-glycans were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CE-MS) to identify N-glycan compositions.35, 36 Released, purified, and methylamidated N-glycans were labeled with Girard’s reagent T (GT) to impart a single positive charge for electrophoretic separation and enhanced ionization efficiency during CE-MS analysis. The compositions and tentative structures of the glycans were based on detected mass and ExPASy GlyConnect database.37 Through CE-MS, 51 N-glycan compositions were identified in total (Table S1), among which 19 and 7 glycans were exclusively present in skin and day 5 wound-edge tissue, respectively. Furthermore, N-glycans conserved in both skin and day 5 wound-edge differ in their relative intensities (Figure 4). Glycans with m/z 855.349 (corresponding to Hex4HexNAc3Neu5Gc1) existed in both Exoκ-GFP samples with similar relative intensities. However, glycan ions at m/z 877.8542 (Hex5HexNAc4) were more abundant in skin Exoκ-GFP, whereas glycan ions at m/z 707.281 (Hex6HexNAc5) were found exclusively in skin Exoκ-GFP. Similarly, glycan ions at m/z 720.232 (Hex10HexNAc2) were only detected in wound edge Exoκ-GFP. The difference in abundance of glycan molecules on Exoκ-GFP surface lends credence to the notion that they play a role in uptake by ωmϕ during wound healing. In vitro inhibition of the C-type lectin receptors in day 3 ωmϕ resulted in decreased uptake of EXOκ-GFP (Figure S3C–D and Supp. Movie S3–4). It was thus of interest to test whether Exoκ-GFP determines the fate of myeloid cells at the wound site. The conventional M1/M2 nomenclature is not appropriate for ωmϕ.23, 38, 39 Recognizing the ambiguity in macrophage nomenclature specifically for tissue macrophages,40–42 we classify in vivo ωmϕ on the basis of the proinflammatory or proresolution/healing phenotype. Incubation of day 3 ωmϕ (proinflammatory phenotype) with Exoκ-GFP and Exonon-GFP isolated from day 3 wound-edge tissue (Figure S3E) caused overt phenotypic changes. On day 7, down-regulation of proinflammatory genes such as Tnfα, Nos2, Cd74 was associated with upregulation of the proresolution gene Cl3 (Figure S3F).

Figure 4. Comparative glycomics of the Exoκ−GFP isolated from skin and wound-edge tissue.

Representative m/z ratios, relative intensities, and proposed structures of N-glycans released from skin and wound-edge tissue derived Exoκ-GFP, methylamidated, labeled with Girard’s reagent T, and analyzed by CE-MS. Data analysis determined that 19 and 7 structures were found exclusive to skin and day 5 wound-edge tissue, respectively.

Design and synthesis of keratinocyte specific lipid nanoparticles to inhibit miRNA packaging within exosome.

Exosomes carry a distinctive repertoire of cargo such as miRNAs.11 Previous studies on RNA profiling of exosomes showed difference in miRNA abundance compared to the parent cells, suggesting that parent cells possess a sorting mechanism that guides specific intracellular miRNAs to enter into the exosomes.12–14 Should the cues for conversion of wound macrophage from a proinflammatory to a proresolution state be driven by keratinocytes via miRNA packaged in exosome, then inhibition of such packaging machinery would result in accumulation of proinflammatory macrophage in vivo. SUMOylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNPA2B1) has been implicated in miRNA packaging within exosomes.15 ExomiRs contain a distinct signature motif known as exomotif. Exomotifs are recognized by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNPA2B1). Exosomal loading of exomiRs is thus controlled by hnRNPA2B1.15 SUMOylation of hnRNPA2B1 causes gain in function, thus improving exosomal loading of miRNA. Thus, it is plausible that inhibition of hnRNPA2B1 in the keratinocytes would impair the microRNA packaging in Exoκ-GFP. We have previously reported keratinocytes targeted delivery of oligonucleotide using functionalized lipid nanoparticles.43 Using a similar approach, we designed keratinocyte-targeted siRNA functionalized lipid nanoparticles (TLNPκ) to inhibit the expression of hnRNPA2B1 in keratinocytes (Figure 5A). Unlike our previous report, the DODAP was replaced by DODMA containing pH-sensitive tertiary amine (Figure 5A). Additionally, the keratinocyte-targeting peptide ASKAIQVFLLAG (A5G33) peptide was conjugated with NHS-PEG2000-DSPE in one-step process for better purification (Figure 5B). A high concentration of Tween 80 (20 mol%) used in nanoparticle formulation for a reduction in the particle size, stabilization of the nanoparticle and increased the skin permeability for local delivery. The Zeta potentials (ζ) of TLNPκ changed from +20 mV to −20 mV in the pH range of 3 to10 demonstrating the pH-sensitive activity of TLNPκ (Figure 5C). Within physiological limit, the neutral or mild positive charge of the lipid nanoparticles evades uptake by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), prolong circulation time and reduce the toxicity.44–46 The siRNA encapsulation efficiency was found to be more than 90% when measured by Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Kit. Gel retardation assay further demonstrated that the siRNA formed complexes with lipid nanoparticles (Figure 5D). The average size of the lipid nanoparticles was found to be 108.9 nm (Figure 5E–F). In a mixed culture comprising of keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, TLNPκ was specifically taken up by the keratinocytes within 4 hours demonstrating targeting specificity and efficiency (Figure 6A–B, Figure S4A–B). This TLNPκ was not cytotoxic in keratinocytes as determined by LDH release (Figure 6C), metabolic viability (Figure S4C), and propidium iodide exclusion (Figure S4D). The uptake of TLNPκ by murine keratinocytes was more rapid compared to non-TLNPκ (Figure 6C, Figure S4E). All materials used for its formulation have prior history of FDA approval for human use and thus offer a clear translational advantage.

Figure 5: Design and synthesis of keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles (TLNPκ) to inhibit miRNA packaging within exosome.

(A) Schematic representation of the keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles TLNPκ. (B) Mass spectrometric analysis of DSPE-PEG2000-A5G33 and DSPE-PEG-NHS using MALDI-TOF. (C) Zeta potentials of TLNPκ at different pH. (D) Gel retardation assay of TLNPκ showing encapsulation efficiency of TLNPκ. (E) Representative Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) image of TLNPκ. Scale, 500 nm. (F) Representative nanoparticle tracking analysis (NanoSight) showing particle size distribution and concentration of non-TLNPκ and TLNPκ.

Figure 6: Specificity, uptake and cytotoxicity of keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles (TLNPκ).

(A) Schematic diagram showing experimental design to test the specificity of TLNPκ in mixed culture. (B) Confocal microscopic images showing selective uptake of TLNPκ by human keratinocytes at 4h compared with non-TLNκ in mixed culture cells (HaCaT: HMEC: BJ-1=1:1:3). K, keratinocyte; F, fibroblasts; E, endothelial cells. Scale; 20 μm. (C) In vitro LDH assay of TLNPk. (n=10) (D) Live-cell confocal images showing rapid uptake of TLNPκ by mouse keratinocytes compared to non-TLNPk. Scale, 10 μm.  Indicate movies in the supplement. Data in C were shown as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the post-hoc Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

Indicate movies in the supplement. Data in C were shown as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the post-hoc Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

Functional characterization of keratinocyte-specific lipid nanoparticles to inhibit miRNA packaging within exosome.

To test whether our siRNA functionalized keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles are effective in inhibiting the packaging of the miRNA within Exoκ-GFP, we utilized commercially available XMIR technology from SBI System Biosciences. XMIR technology takes advantage of normal cellular processes to package a specific miRNA into exosomes using the XMotif RNA sequence tag. Transfection of XmiR-21–5p to human keratinocytes increased the abundance of miR-21–5p in cells as well as in the exosome isolated from keratinocytes cultured conditioned media (Figure S5A–B). Delivery of TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 to human keratinocyte significantly suppressed hnRNPA2B1 expression (Figure 7A–B). Transfection of XmiR-21–5p to cells treated with either TLNPκ/si-control or TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 showed no significant difference in the number of exosomes released by keratinocytes (Figure 7C). However, quantification of exosomal RNA content and miR-21–5p abundance within the exosome from TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 and XmiR-21–5p treated keratinocytes showed significant reduction suggesting that TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 was successful in inhibiting the miRNA packaging within the exosome in keratinocytes (Figure 7D–F).

Figure 7: TLNPk/si-hnRNPA2B1 inhibits packaging of miRNA within the exosome in keratinocyte.

(A) Schematic diagram showing experimental design to test the efficacy of TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 in inhibiting miRNA packaging within the exosome in keratinocyte. (B) Western blot analysis of hnRNPA2B1 in human keratinocytes 72 h after treatment with TLNPκ encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1. Quantification of hnRNPA2B1 expression from immunoblots. (n=8,7) (C) The exosomes isolated from keratinocyte conditioned media 48h after transfection and Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis was done. The exosome concentration in the conditioned media 48 h after treatment with TLNPκ encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1were plotted graphically. (n=12) (D) High-resolution automated electrophoresis of RNA isolated from exosomes in the conditioned media 48 h after treatment with TLNPκ encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1were plotted graphically. (E) The RNA concentration per 109 exosomes in the conditioned media 48 h after treatment with TLNPκ encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1were plotted graphically. (n=12) (F) The abundance of miR-21–5p in exosome isolated from the conditioned media 48 h after treatment with TLNPκ encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1were plotted graphically. (n=12). Data in B, C, E and F were shown as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

Delivery of keratinocyte-specific lipid nanoparticles encapsulating si-hnRNPA2B1 compromised quality of wound closure.

Based on observations from in vitro studies on the role of Exoκ−GFP in the conversion of macrophage phenotype (Figure S3E), we postulated that in vivo delivery of TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 to inhibit miRNA packaging in keratinocytes will compromise the quality of wound healing in mice. Comparable to findings of in vitro studies, delivery of TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 to murine keratinocyte significantly suppressed hnRNPA2B1 expression (Figure 8A–D, Figure S6A). Interestingly, no significant difference in the number of exosomes released at the wound-edge was observed (Figure S6B). Furthermore, wound closure in both TLNPκ/si-control and TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 groups were comparable (Figure 8E, Figure S6C–D). However, at day 10 in mice treated with TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1, persistent accumulation of inflammatory cells was noted in the granulation tissue (Figure 8F). These inflammatory cells were identified to be as ωmϕ (Figure 8G, Figure S6E). Unlike the scanty ωmϕ that exhibit proresolution marker arginase in TLNPκ/si-control group, these ωmϕ abundant in TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treated group expressed proinflammatory marker iNOS even at day 10 post-wounding (Figure 8H–I, Figure S6F–G). Such increased abundance of ωmϕ in the granulation tissue of TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treated group may not be attributed to increased recruitment on the basis of comparable neutrophil or macrophage counts on day 3 post-wounding (Figure S7). These ωmϕ, exhibiting proinflammatory phenotype, persisted in the repaired skin even after the wound was closed following TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treatment (Figure S8). Such presence of proinflammatory ωmϕ at the granulation tissue in mice treated with TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 lend credence to the notion that the cues for conversion of ωmϕ from proinflammatory to proresolution state comes as miRNA packaged in keratinocyte-derived exosomes.

Figure 8: Delivery of keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles encapsulating si-hnRNPA2B1 compromised the quality of wound closure.

(A) Western blot analysis of hnRNPA2B1 in murine keratinocytes 48 h after treatment with TLNPk encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1. β-actin was used as loading control. Quantification of hnRNPA2B1 expression from immunoblots. (n=6) (B) Schematic diagram showing excisional wounding (6mm stented wound), application of TLNPk encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1 and tissue harvesting time points in C57BL/6 (wild type) mice. (C) Confocal microscopic image showing localization of DID-labeled TLNPk (red) in the epidermis (green) at 24h after post-treatment with DID-labeled TLNPk by subcutaneous injection. Scale, 50 μm. (D) Representative coimmunofluorescence images showing hnRNPA2B1 (green) and DAPI counterstaining in C57BL/6 mice at day 6 post wounding. White dashed lines indicate the dermal-epidermal junction. Scale, 50μm. (E) Quantification of excisional stented punch wounds (6mm) at different days by digital planimetry following delivery of TLNPk encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1. (n=6,8) (F) Representative Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining of day 10 murine wound tissue treated with TLNPk encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1. Scale, 200μm (for mosaic images) and 20μm (for inset images). (G) Representative coimmunofluorescence staining of F4–80 (red) with DAPI counterstaining in wound-edge tissue at day 10 post-wounding in C57BL/6 mice treated with either scramble or si-hnRNPA2B1 encapsulated keratinocyte targeted lipid nanoparticles. Scale, 50μm. Quantification of F4–80 intensity in wound-edge tissue at day 10 post-wounding. Each dot corresponds to one quantified ROI, except the blue and red dots, which correspond to the mean of each mouse. At least 5 ROI per mouse. (n = 4) (H) Representative coimmunofluorescence staining of F4–80 (red) and Arginase (green; proresolution macrophage marker) with DAPI counterstaining in day 10 wound-edge tissue of C57BL/6 mice treated with TLNPk encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1. The colocalization of red and green are shown as white dots. Scale, 20μm. (I) Representative coimmunofluorescence staining of F4–80 (red) and iNOS (green; proinflammatory macrophage marker) with DAPI counterstaining in day 10 wound-edge tissue of C57BL/6 mice treated with TLNPκ encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1. The colocalization of red and green are shown as white dots. Scale, 20μm. Data in A, G and E were shown as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

To investigate the significance of abundant proinflammatory ωmϕ in the day 10 granulation tissue of TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treated mice, we tested the functional property of the re-epithelialized skin by measuring the barrier function post-closure. The barrier function of the TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 group was significantly compromised demonstrating that indeed wound closure was impaired (Figure 9A). Restoration of barrier function of the repaired skin is a necessary component of functional wound healing.44, 47–49 The terminally differentiating structural protein loricrin forms 70–80% of the cornified envelope contributes to the protective barrier function of skin.49–51 The abundance of loricrin in the re-epithelialized skin was significantly compromised following TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treatment (Figure 9B). Furthermore, lower expression of other junctional proteins such as ZO-1, ZO-2, filaggrin and occludins was also observed at day 10 post-wounding in TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treated group compared to TLNPκ/si-control group (Figure 9C). Taken together, these observations explain how functional wound closure is impaired in mice treated with TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1. Thus, impairment in miRNA packaging in keratinocyte exosomes of the skin impaired resolution of inflammation and compromised functional wound closure.

Figure 9: Delivery of keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles encapsulating si-hnRNPA2B1 compromised the quality of wound closure.

(A) Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) after C57BL/6 mice treated with TLNPκ encapsulating either si-control or si-hnRNPA2B1. (n=10) (B) Representative coimmunofluorescence staining of loricrin with DAPI counterstaining in wound-edge tissue at day 10 post-wounding in C57BL/6 mice treated with either scramble or si-hnRNPA2B1 encapsulated keratinocyte targeted lipid nanoparticles. Scale, 200μm. Quantification of loricrin intensity in wound-edge tissue at day 10 post-wounding. Each dot corresponds to one quantified ROI, except the blue and red dots, which correspond to the mean of each mouse. At least 5 ROI per mouse. (n = 4) (C) TLNPκ/si-hnRNPA2B1 treatment compromised the expression of ZO-1 (green), ZO-2 (red), filaggrin (green) and occludin (red) in murine skin at day 10. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Dermal-epidermal junction is indicated by a dashed white line. Scale bars, 50 μm. The abundance of junctional proteins was quantified. Each dot corresponds to one quantified ROI, except the blue and red dots, which correspond to the mean of each mouse. At least 5 ROI per mouse. (n = 3, 4). Data expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we developed a method of isolating Exoκ−GFP in tissue for studying keratinocyte-exosome crosstalk during wound healing. This work provides critical insight into the significance of Exoκ−GFP in the resolution of wound inflammation and determination of functional wound closure. Exoκ−GFP showed abundance of small bp RNA (<100 bp) in day 5 wound-edge tissue. Exoκ-borne miRNA signals enable crosstalk between resident keratinocytes of the skin with visiting ωmϕ. Glycan ions with high mannose was only detected in wound-edge Exoκ. Wound macrophages are known to possess mannose receptors. Mannose-functionalization is commonly used to target nanoparticles for ωmϕ uptake. In this work, Exoκ were taken up by ωϕ in the wound-edge tissue. Such uptake caused phenotypic changes in ωmϕ consistent with the resolution of inflammation. Blockade of miRNA transfer via Exoκ−GFP to ωmϕ by knocking down hnRNPA2B1 caused persistence of proinflammatory ωmϕ. Thus, exosomal miRNA packaging in skin keratinocytes modify wound inflammation response. Impaired resolution of wound inflammation, caused as above, hindered functional wound healing by compromising restoration of skin barrier function at the site of repair. Findings of this work lay the framework of an emerging paradigm wherein exosome-borne molecular signals drive crosstalk between different cellular compartments in a way that directly determines the fate of wound healing outcomes. Such advancement in our understanding of wound healing unveils heretofore unknown therapeutic targets that may be exploited to design productive wound-care strategies.

METHODS

Cells and cell culture.

Immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) were grown in Dulbecco’s low-glucose (1g/L) modified Eagle’s medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) as described previously.52 Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs) were cultured in MCDB-131 medium supplemented 10 mm l-glutamine, and 100 IU/ml of penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen), as described previously.53 Human skin fibroblast BJ cells (ATCC® CRL-2522™) were obtained from ATCC and were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium, (Catalog No. 30–2003) as per the instruction provided. Mouse keratinocytes (KERA-308) were purchased from Cell line Services (CLS Germany) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s high-glucose (4.5g/L) modified Eagle’s medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts were purchased from Millipore Sigma (PMEF-HL) and were cultured as per manufacturer’s instruction. For isolation of wound macrophages (ωmϕ), circular (8 mm) sterile Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) sponges were implanted subcutaneously on the backs of 8 to 12 week-old mice.54 Sponge-infiltrated wound mϕ (CD11b+) were obtained from day 3 wound cell infiltrate by magnetic bead-based sorting as previously described.55, 56 The isolated cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media. The cells were maintained in a standard culture incubator with humidified air containing 5% CO2 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (AA) (Life Technologies) unless stated otherwise. All experiments involving isolation or uptake of exosomes were performed with exosome depleted FBS.

Isolation of exosome from cell culture media (EV-TRACK ID: EV190103).

Cell culture supernatant (using cells cultured with media described above and 10% Gibco Exosome-Depleted FBS (ThermoFisher Scientific)) was centrifuged at 3400g for 15 min and the supernatant was collected. Extracellular vesicles were isolated from the supernatant using differential ultracentrifugation (Beckman Coulter Optima Max-XP Ultracentrifuge, rotor TLA120.2) as described in figure S1. Pellets were washed by resuspending in PBS and re-pelleting via a second round of ultracentrifugation. These pellets were then resuspended in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C with magnetic CD9, CD63 and CD81 Dynabeads (Invitrogen). The exosomes-attached to the beads were magnetically separated from flow through using a magnetic microcolumns (μ columns from Miltenyi Biotec MACS). The flow through eluent (membrane particles and apoptotic bodies) was kept and re-pelleted for further analysis (2h at 245,000g). For Western blot and flow cytometry, the exosomes were not removed from the magnetic beads. For Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis or SEM imaging, exosomes were eluted from the beads using elution buffer (ExoFlow Exosome Elution Buffer, System Biosciences) as per manufacture’s protocol. This method was submitted to EV track.27

Isolation of keratinocyte-derived exosome from murine tissue.

EVs and keratinocyte-derived exosomes were isolated from mouse tissue following transfection with Keratin 14 promoter driven plasmids encoding murine CD63, CD9 and CD 81 with GFP reporter “in frame”. The murine skin and wound-edge tissue were collected and homogenized, suspended in PBS and vortexed to release exosomes from tissue. The solution was briefly centrifuged and the supernate collected and centrifuged at 5000g for 15 min followed by 20,000 g for 45 min. The supernatant was incubated overnight at 4°C with GFP-Trap magnetic agarose beads (Chromotek Catalog # gtma-100) (12 μL GPF-Trap beads per 0.15 g tissue). Exosome isolation from GFP-Trap beads utilized magnets to isolate the beads, enabling the eluent to be removed. The GFP-Trap beads were washed thrice in PBS. Finally, elution of intact beads was accomplished by mixing with glycine (0.2M, pH 3) for 30 seconds, a process that was repeated 5 times. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 using 1.0 M Tris, and EXOκ-GFP pellets were collected by ultracentrifugation (2 h at 245,000g). The flow through was next incubated with magnetic pan-CD beads (Miltenyi Biotec Catalog # 130–117-039) for 2 h at room temperature that were isolated from flow through to recover the non-keratinocytes derived exosome as described above for Invitrogen Dynabeads.

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS).

Exosome-protein binding was also measured by the change in diffusion and anisotropy of a fluorescently labeled antibody (TSG101-PE) incubated in the presence of exosomes or other extracellular vesicles using a two-channel fluorescence correlation spectroscopy system (Confocor 2, Zeiss) attached to an Axiovert200 M inverted microscope (Zeiss).57 The system measures a characteristic diffusion time (τD) of a fluorophore as determined by fitting fluorescent decay within a confocal volume to an autocorrelation curve using the Eq. (1), where N is particle concentration and Q is a factor relating to the ellipticity of the confocal volume:

| (1) |

Autocorrelation best fit curves identify change in particle diffusion with curves shifted to the left demonstrating faster diffusion (smaller τD); exemplary best fit curves are shown, where the curves are fitted using a one-component fit identifying an average characteristic diffusion time for the fluorophores. For fluorophores bound to exosomes, this will provide qualitative evidence of exosomal binding.

Fluorescence anisotropy.

Fluorescence anisotropy experiments were conducted using a two-channel fluorescence correlation system where both channels are equipped with crossed analyzers, one perpendicular and one parallel to the emitted laser light. The emitted light divides into two separate beams of equal intensity, which are guided into each of the two APD channels. The anisotropy can be calculated using Eq. (2).

| (2) |

where I1 and I2 are the intensities of the parallel and perpendicular channels, respectively.57, 59 A correction factor for difference in analyzer sensitivity was not utilized as this factor does not alter significance of change in anisotropy between different conditions. Anisotropy experiments are complementary to autocorrelation analysis because they provide information about the short-range mobility of the tracer molecules, namely the change in rotational diffusion. Autocorrelation curves shown are examples of curves collected with concentration normalized; anisotropy data were collected using 10s runs for each data point.

N-Glycan analysis.

Denaturation solution, consisting of 0.1% SDS (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) and 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), was added to the exosome sample and incubated at 60 °C for 1 h. After that, nonidet P40 substitute (NP-40, Roche Diagnostics Corp, Indianapolis, IN) was added to encapsulate SDS. The sample was then incubated with Peptide N-Glycosidase F (PNGase F, New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA) at 37 °C for 18 h. Cleaved N-glycans were purified through solid-phase extraction on an active charcoal phase (Micro SpinColumns, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). For methylamidation60, 61, purified and dried glycans were dissolved in 5 μL of DMSO (Fisher Chemical, Fair Lawn, NJ), containing 2 M methylamine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 1 M 4-methylmorpholine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 5 μL of 100 mM (7-Azabenzotriazol-1-yloxy) tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyAOP, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The reaction proceeded at room temperature in the dark for 4 h and was terminated with addition of 240 μL of 85% acetonitrile (OmniSolv, Billerica, MA). Methylamidated N-glycans were purified through solid-phase extraction on a hydrophilic interaction phase (Amino Micro SpinColumns, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). To impart a +1 charge for electrophoresis, glycans were labeled with Girard’s reagent T (GT; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Briefly, 25 μL of 0.02 M GT in 10% (v/v) acetic acid was added to purified glycans and incubated at 55 °C for 4 h, and the reaction mixture was dried in a CentriVap concentrator to remove excess acetic acid and water.

CE-MS analysis35 of the N-glycans was conducted on a CESI 8000 instrument (SCIEX Separations, Framingham, MA) with a neutral capillary cartridge (30 μm i.d. x 90 cm length; Opti-MS, B07368, SCIEX Separations) and an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). GT-labeled N-glycans were dissolved in 10 μL of 0.5% acetic acid (v/v). Sample was injected into the capillary hydrostatically at 3 psi for 25 s and electrophoretically separated with an applied potential of 25 kV and pressure of 3 psi. The capillary was connected to the mass spectrometer through an electrospray interface with an applied potential of 1090 V. MS data from positive ions ranging from 200 to 2000 m/z were collected. The detected masses were searched on Expasy GlycoMod, and tentative structures were assigned based on previously reported structures on Expasy GlyConnect. Relative intensities of the N-glycans were calculated with the Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser algorithm Genesis where the signal was boxcar averaged (7 points) with mass tolerance 30 ppm.

Flow cytometry.

Exosome markers were assessed using PE anti-TSG101 (1:100, NB200–112PE, Novus Biologicals), PE anti -flotillin-1 (1:200, ab225165, Abcam) by incubating the antibodies at the noted concentrations with the beads for 90 minutes at room temperature. Additional exosome markers, anti-Alix (1:100, 92880 Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-HSP90 (1:100, ab59459, Abcam) were first incubated with beads for 90 minutes at room temperature followed by magnetic separation using PBS to remove excess antibodies and incubation of beads next with the secondary antibody. Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200, ab150077). PE fluorescence was determined using PE channel. Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence was determined using FITC channel. For the membrane integrity assay, human keratinocytes were incubated with Propidium iodide (1mg/ml) and the percentage of viable cells was measured in FL2 channel.62 Heat killed human keratinocytes were used as positive control. Samples were run on an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Accuri Cytometers, MI, USA) or LSRFortessa X‐20 flow cytometers (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). Data were collected from 5000 – 10,000 events at a flow rate of 250–300 events/s and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, OR, USA).

Synthesis of DSPE-PEG2000-A5G33.

DSPE-PEG2000-A5G33 was synthesized through the conjugation of A5G3344 (sequence: ASKAIQVFLLAG, Genscript, NJ, USA) and DSPE-PEG2000-NHS (Nanocs, Boston, MA, USA). Lipid peptide conjugation was done by dissolving 20 mg DSPE-PEG2000-NHS in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with a solution of A5G33 in DMSO and 10 μL trimethylamine (TEA). The reaction was performed in an oxygen-free environment (nitrogen purge) at room temperature for 24 hours. The resulting mixture was dialyzed against deionized water using a slide-a-lyzer dialysis cassette (Molecular weight cut-off, MWCO 3500) for 48 h to remove impurities. The final solution was lyophilized and the powder was stored at −20 °C for further use. DSPE-PEG2000-A5G33 was characterized using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (15 T FT-ICR Bruker Daltonics Inc.).

Preparation of keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles (TLNPk).

TLNPk were prepared by using a modified ethanol dilution method as described previously44. Briefly, DOTAP/DODMA/DOPC/DSPE-PEG2000-A5G33/Tween80 (20/30/27/3/20, mol/mol) were dissolved in ethanol, and mixed with siRNA in triethylammonium acetate buffer (20 mM, pH 4.5). The mixture was further diluted using PBS (10 mM phosphate, 135 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The ethanol and free siRNA were removed by dialysis using a slide-a-lyzer dialysis cassette (Molecular weight cut-off, MWCO 20000). DSPE-PEG2000-A5G33 was replaced with DSPE-PEG2000 in the non-targeted lipid nanoparticles (non-TLNPκ). If lipophilic fluorescence dye DiD were chosen to label the LNPs, 0.2% mol/mol amount of dye was added into the above formulation recipe.

Encapsulation efficiency of TLNPκ.

Encapsulation efficiency was performed by the Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) as described previously.44 The unencapsulated siRNA content and the total siRNA content that was obtained upon lysis of the TLNPκ by 1% Triton were determined according to the manufacturer’s instruction using Multi-Mode Microplate Readers (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA) at 480 nm λex and 520 nm λem. The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of siRNA was calculated with the following equation:

The encapsulation efficiency of siRNA encapsulated keratinocyte targeted lipid nanoparticles (TLNPk/si) was also re-verified using gel retardation assay via 1% agarose gel. Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 20 min and visualized under a UV transilluminator (Bio-Rad laboratories, CA, USA).

Electron microscopy.

The morphology of exosomes and TLNPk/si_hnRNPA2B1 was observed by transition electron microscopy (TEM, Japan). Briefly, the particles were ultracentrifuged at 250,000 g at 4 °C, then the pellet was dispersed into deionized water and dropped on a copper grid, stained with NanoVan (vanadium-based negative stain from Nanoprobes.com, Yaphank, New York) and viewed on a Tecnai G2 12 Bio Twin electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) at the Electron Microscopy Center at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

The morphology of exosome and other EVs was checked by scanning electron microscopy. Briefly, pellets containing either exosomes or eluent were resuspended in ddH2O with 0.1% formalin or other buffer and dropped onto clean silica wafers. After drying, samples were desiccated in a vacuum chamber for at least 12 hours before analysis. Images were obtained after gold sputter coating using a field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL 7800F, JEOL Japan) at a beam energy of 5 or 10 kV.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis.

Mean particle diameter and concentration of extracellular vesicles and TLNκ were analyzed by Nanosight NS300 with a 532 nm laser and SCMOS camera (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) as previously described.44 Briefly, samples were diluted 100: 1 or as needed in fresh milliQ to obtain 5–100 particles/frame. Samples were typically analyzed using 5 runs of 30s collecting 25 frames per second (749 frames per run) with viscosity determined by the temperature and camera level highest available for sample (typically 15 or 14). The syringe pump speed was 60. NTA automatically compensates for flow in the sample so only Brownian motion is used for size determination. For processing results, the detection threshold was typically 5 with automated blur size and max jump distance. Standard 100 nm latex spheres were run at 1000:1 dilution in milliQ to check the instrument performance. Data were analyzed by NTA 3.0 software (Malvern Instruments).

Zeta potential analysis.

Surface charge (ζ potential) measurement of TLNPκ was determined by Zetasizer (Nano-Z, Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). All samples were dispersed in double-distilled water and tested in volume-weighted size distribution mode. Aliquots of TLNPκ containing antimiR-107 were diluted in PBS with a series of pHs (50mM, from 2–11) to determine the pH dependency of surface charge.

LDH release assay.

Cytotoxicity of TLNPk was analyzed by measuring the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage in the media using the TOX-7 in vitro toxicology kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as previously described.63 Briefly, HaCaT cells were seeded in 12-well plates (0.1 × 106 cells/well), and incubated overnight. The media were changed when the cells were treated with TLNPκ/si_hnRNPA2B1. After incubation for the designated time (24 h and 48 h), cells culture media were collected and centrifuged, then the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and incubated with the mixture of the assay substrate, enzyme and dye solutions for 20–30 min in dark at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by adding 1N HCl to each well. LDH absorbance was measured at 490 nm using the Bio-TEK ELX 808IU micro plate reader (Bio-TEK INSTRUMENTS, INC, Winooski, VT).

MTT assay.

Viability of keratinocytes post nanoparticle treatment was measured using a Vybrant MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24 h after treatment, cells were incubated in medium containing 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) for 4–6 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After MTT treatment, medium was removed, and DMSO was added (10–20 min at 37°C with 5% CO2) to solubilize formazan produced as a result of MTT metabolism. DMSO extract from each well (100 μl) was collected in a 96-well plate, and formazan content was determined by reading absorbance at 540 nm.64

Lipid nanoparticles and exosome uptake assay.

For the cellular uptake of keratinocyte-targeted lipid nanoparticles studies, mixed culture of three different cells was performed. 1×105 cells (HaCaT: HMEC: BJ1=1:1:3) were seeded in a 12-well plate in mixed media with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics and incubated overnight. DiD-loaded TLNPκ/si_hnRNPA2B1 and non-TLNPκ/si_hnRNPA2B1 were prepared and added into the cells, then incubated at 37 °C. After 2 hours, cells were washed using PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. HaCaT cells and HMEC were immunostained by K14 and CD31 respectively. Confocal images were acquired with a confocal laser-scanning system (CARL ZEISS confocal microscope LSM 888). For live imaging of the uptake of TLNPκ by Kera 308, Kera cells were seeded in 4-well tissue culture chambers at a density of 2 × 104 cells and incubated overnight. DiD-loaded TLNPκ_FAM-siRNA and non-TLNPκ_FAM-siRNA were prepared and incubated with the cells. The cellular uptake was visualized for about 95 minutes.

For uptake of exosome studies by wound macrophages, Exoκ-GFP were isolated from murine skin. The concentration of the exosome was measured by Nanoparticle tracking analysis. The exosomes were stained with DiO and added to the day 3 ωmϕ and live cell imaging was performed. For blocking the C-type lectin receptors, a cocktail of neutralizing antibodies was used. Murine mincle (Mabg-mmel; Sigma), mouse dectin 1(MAB17561; R&D systems) and mouse SIGNR1 (AF18836; R&D systems) were used.

Ultrahigh Resolution Fourier Transform Mass Spectrometry.

The accurate mass of the samples was determined using mass spectrometry. High-resolution mass spectrometry analyses were carried out in The Ohio State University, Campus Chemical Instrument Center’s Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility (OSU CCIC MSP) by using a 15 T Bruker SolariXR FT-ICR instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA).65 Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) was used with the alpha cyano hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) matrix in the positive ion mode. The matrix was purchased from Bruker Daltonics (Billarica, MA). The third harmonic of a Yag/Nd laser was used (351 nm) for MALDI with a 25% laser power. The samples were mixed with the saturated solution of the HCCA matrix with a matrix: analyte ratio of around 100:1. The resolution of the FT-ICR instrument was set to 150,000 at around m/z 2,500. The detection range was m/z 300–13,000 but no ions were observed beyond m/z 5,000. Standard FT-ICR ion optics parameters were used to maximize ion detection efficiency in the applied m/z range.

Transfection of XmiR-21 mimics.

DharmaFECT™ 1 transfection reagent was employed to transfect HaCaT cells with XmiR-21 (100nM) (Dharmacon) as described previously.49 Cells and media were collected 48 h after transfection for further analysis as indicated.

Animals.

Male C57BL/6 mice (aged 8–10 weeks) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. All animal studies were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Laboratory Animal Resource Center of Indiana University. No statistical methods were used to predetermine the sample size. Power analysis was not necessary for this study. The animals were tagged and grouped randomly using a computer-based algorithm (www.random.org).

Wound models and in vivo TLNPk/siRNA delivery.

For wounding, two 6-mm diameter full-thickness excisional wounds were developed on the dorsal skin of mice with a 6-mm disposable biopsy punch and splinted with a silicon sheet to prevent contraction thereby allowing wounds to heal through granulation and re-epithelialization.66–68 TLNP κ/si-control and TLNP κ/si-hnRNPA2B1 were administrated into the wound edge by subcutaneous injection. For isolation of exosomes from wound-edge, four 8 mm diameter full-thickness excisional wounds were developed on the dorsal skin of mice with an 8-mm disposable biopsy punch without any stent. During the wounding procedure, mice were anesthetized by low-dose isoflurane (1.5%−2%) inhalation as per standard recommendation. Tissue from the wounds (skin) was snap-frozen and stored at −80°C until harvested for exosome collection described above. Each wound was digitally photographed at the time point indicated. Wound size was calculated by the ImageJ software.22

The animals were euthanized at the indicated time and wound edges were collected for analyses. For wound-edge harvest, 1–1.5 mm of the tissue from the leading edge of the wounded skin was excised around the entire wound. The tissues were snap-frozen and if used for exosome harvest, left in −80°C until harvested for exosome collection described above. If used for IHC, tissues were collected either in 4% paraformaldehyde or in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound.

Tissue nanotransfection 2.0.

In vivo TNT was performed as described previously with a modification in the chip design.31 The hollow microneedle array was fabricated on a double side polished Silicon wafer using a standard semiconductor process in a cleanroom environment. First, the Si wafer was wet oxidized in a furnace at 1150 °C to grow 4 μm thermal oxide on both sides that served as a hard mask during the deep silicon etching. A 10 μm thick, positive photoresist of AZ 9260 was spin-coated on one side of the silicon wafer followed by a prebake at 110 °C for 10 min. A direct laser writing system was used to expose a layout of 25 μm circle arrays followed by development in a diluted AZ400K solution to remove the exposed area. The 4 μm oxide was removed by a plasma etcher using CHF3 chemistry. The wafer was then transferred to another plasma etching system to perform a deep Si etching called Bosch process, a common semiconductor process to achieve a vertical etching profile with a high-aspect ratio. After silicon etching of about 350 – 450 μm in depth to form the reservoir arrays, the wafer was flipped for the next step to etch the hollow microneedle arrays. A donut-shaped pattern was exposed onto the resist and the pattern was transferred to the oxide using the same set of steps mentioned above. Then, the wafer was etched by the Bosch process until the hollow microneedles are connected to the reservoirs so that the cargo or the plasmid DNA fluid can freely flow from the reservoir to the hollow microchannel. The SEM images showed the fabricated silicon hollow microneedle array (Fig. 1C) that has a length of 170 μm, an outer diameter of 50 μm and a hollow diameter of 4 μm. When an electric pulse was applied between the TNT chip and the tissue, the negatively charged plasma DNA will travel from the reservoir to nearby target cells by electrophoresis and enter them by electroporation. To test the TNT2.0 delivery efficiency, FAM-DNA (5′/56-FAM/TACCGCTGCGACCCTCT-3′) was used in murine skin.

Trans-epidermal water loss.

TEWL serves as a reliable index to evaluate the skin barrier function in vivo 23–25. TEWL was measured from the skin and wounds using DermaLab TEWL Probe (cyberDERM, Broomall, PA). The data were expressed in g.m−2.h−1.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR.

RNA from cells or exosome was extracted using miRVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion) according to the manufacture’s protocol.21, 69 For determination of miR expression, specific TaqMan assays for miRs and the TaqMan miRNA reverse transcription kit were used, followed by real time PCR using the Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). mRNA was quantified by real-time or quantitative (Q) PCR assay using the double-stranded DNA binding dye SYBR Green-I.21, 69

High-resolution automated electrophoresis of RNA.

The RNA isolated from Exoκ-GFP was analyzed in Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California).70

Western blots.

Western blot was performed using antibodies against human hnRNPA2B1 (Sigma-Aldrich; SAB1403931, 1:500), mouse hnRNPA2B1 (Sigma-Aldrich; HPA001666, 1:200), TSG101 (Abcam; ab125011, 1:1000), Alix (Novus Biologicals; JM 85–31, 1:1000), HSP90 (Abcam; ab59459, 1:1000), Flotillin 1 (Abcam; ab133497, 1:200), GM130 (Abcam; ab52649, 1:1000), Prohibitin (Abcam; ab28172, 1:200). Signal was visualized using corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham, 1:3,000) and ECL Plus™ Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Amersham). β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich; A5441, 1: 2000) served as loading control.21, 22

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and microscopy.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously.71 Immunostainings of F4/80 (Bio-Rad, MCA497R; 1:200), K14 (Covance, PRB-155P-100; 1:400), GFP (Abcam, ab13970; 1:500), MPO (Abcam, ab9535; 1:50), Arginase (Abcam; 203490, 1:100), iNOS (Abcam; ab115819, 1:100), hnRNPA2B1(Sigma-Aldrich; HPA001666, 1:50), Occludin (Invitrogen, 711500; 1:200), ZO-1 (Invitrogen, 617300; 1:200), ZO-2 (Invitrogen, 389100; 1:200), Loricrin (Biolegend, PRB-145P; 1:400), Filaggrin (Covance, PRB-417P; 1:500) CD31 (BD Pharmingen, 550274; 1:400), Col1A2 (Santa Cruz, sc-393573; 1:200), CDH5 (Abcam; ab91064, 1:200), were performed on paraffin and cryosections of skin sample using specific antibodies as indicated.57 The specificity of the antibodies was validated using rabbit isotype control (Abcam, ab27478; 1:400). Briefly, the sections blocked with 10% normal goat serum, and incubated with specific antibodies overnight at 4°C. Signal was visualized by subsequent incubation with fluorescence-tagged appropriate secondary antibodies (Alexa 488-tagged α-rabbit, 1:200; Alexa 568-tagged α-rabbit, 1:200; Alexa 568-tagged α-rat, 1:200, Alexa 488-tagged α-chicken, 1:200) and counter stained with DAPI. Images were captured by microscope using super-resolution airyscan laser-scanning confocal system (CARL ZEISS confocal microscope LSM 888) and (Axio Scan.Z1, Zeiss, Germany). Quantification of fluorescent intensity of image was analyzed using Zen software (Zen blue 3.1) and ImageJ software with colocolization plugin.72, 73

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) v8.0 was used for statistical analyses. No statistical methods were used to predetermine the sample size. The ΔΔCt value was used for statistical analysis of all RT-qPCR data. Statistical analysis between multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance with the post-hoc Sidak or Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Statistical analysis between two groups were performed using unpaired Student’s two-sided t tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significance levels and exact P values were indicated in all relevant figures. Data were assumed to be normally distributed for all analyses conducted. Data for independent experiments were presented as means ± SEM unless otherwise stated.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Integrated Nanosystems Development Institute (INDI) for use of their JEOL 7800-f Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope, which was awarded through NSF grant MRI-1229514. The 15 T Bruker SolariXR FT-ICR instrument was supported by NIH Award Number Grant S10 OD018507. This study was primarily supported by junior faculty startup pack from ICRME to SG. In addition, this study was also supported in part by NR015676 and DK114718 to SR and NS042617 to CKS. This work also acknowledges the support of Lilly Indiana Collaborative Initiative for Talent Enrichment (INCITE) program.

Footnotes

Financial Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed KA; Xiang J, Mechanisms of Cellular Communication through Intercellular Protein Transfer. J. Cell Mol. Med 2011, 15, 1458–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peinado H; Lavotshkin S; Lyden D, The Secreted Factors Responsible for Pre-Metastatic Niche Formation: Old Sayings and New Thoughts. Semin. Cancer Biol 2011, 21, 139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo M; Raposo G; Thery C, Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 2014, 30, 255–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faict S; Muller J; De Veirman K; De Bruyne E; Maes K; Vrancken L; Heusschen R; De Raeve H; Schots R; Vanderkerken K; Caers J; Menu E, Exosomes Play a Role in Multiple Myeloma Bone Disease and Tumor Development by Targeting Osteoclasts and Osteoblasts. Blood Cancer J 2018, 8, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosseinkhani B; Kuypers S; van den Akker NMS; Molin DGM; Michiels L, Extracellular Vesicles Work as a Functional Inflammatory Mediator between Vascular Endothelial Cells and Immune Cells. Front. Immunol 2018, 9, 1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J; Faict S; Maes K; De Bruyne E; Van Valckenborgh E; Schots R; Vanderkerken K; Menu E, Extracellular Vesicle Cross-Talk in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment: Implications in Multiple Myeloma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 38927–38945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu R; Greening DW; Zhu HJ; Takahashi N; Simpson RJ, Extracellular Vesicle Isolation and Characterization: Toward Clinical Application. J. Clin. Invest 2016, 126, 1152–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thery C; Ostrowski M; Segura E, Membrane Vesicles as Conveyors of Immune Responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2009, 9, 581–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zgheib C; Hilton SA; Dewberry LC; Hodges MM; Ghatak S; Xu J; Singh S; Roy S; Sen CK; Seal S; Liechty KW Use of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Conjugated with MicroRNA-146a to Correct the Diabetic Wound Healing Impairment. J. Am Coll Surg 2019, 228, 107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kojima R; Bojar D; Rizzi G; Hamri GC; El-Baba MD; Saxena P; Auslander S; Tan KR; Fussenegger M Designer Exosomes Produced by Implanted Cells Intracerebrally Deliver Therapeutic Cargo for Parkinson’s Disease Treatment. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janas T; Janas MM; Sapoń K; Janas T, Mechanisms of RNA Loading into Exosomes. FEBS Lett 2015, 589, 1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creemers EE; Tijsen AJ; Pinto YM, Circulating MicroRNAs: Novel Biomarkers and Extracellular Communicators in Cardiovascular Disease? Circ.Res 2012, 110, 483–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guduric-Fuchs J; O’Connor A; Camp B; O’Neill CL; Medina RJ; Simpson DA, Selective Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Export of an Overlapping Set of MicroRNAs from Multiple Cell Types. BMC genomics. 2012, 13, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J; Li S; Li L; Li M; Guo C; Yao J; Mi S, Exosome and Exosomal MicroRNA: Trafficking, Sorting, and Function. Genomics, Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015, 13, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villarroya-Beltri C; Gutiérrez-Vázquez C; Sánchez-Cabo F; Pérez-Hernández D; Vázquez J; Martin-Cofreces N; Martinez-Herrera DJ; Pascual-Montano A; Mittelbrunn M; Sánchez-Madrid F, Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 Controls the Sorting of MiRNAs into Exosomes through Binding to Specific Motifs. Nat. Commun 2013, 4, 2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker JN; Mitra RS; Griffiths CE; Dixit VM; Nickoloff BJ, Keratinocytes as Initiators of Inflammation. Lancet. 1991, 337, 211–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pastore S; Mascia F; Mariani V; Girolomoni G, Keratinocytes in Skin Inflammation. Expert Rev. Dermatol 2006, 1, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miodovnik M; Koren R; Ziv E; Ravid A, The Inflammatory Response of Keratinocytes and its Modulation by Vitamin D: The Role of MAPK Signaling Pathways. J. Cell Physiol 2012, 227, 2175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha M; Sen CK; Singh K; Das A; Ghatak S; Rhea B; Blackstone B; Powell HM; Khanna S; Roy S, Direct Conversion of Injury-Site Myeloid Cells to Fibroblast-Like Cells of GranulationTissue. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas T; Waisman A; Ranjan R; Roes J; Krieg T; Muller W; Roers A; Eming SA, Differential Roles of Macrophages in Diverse Phases of Skin Repair. J. Immunol 2010, 184, 3964–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das A; Ganesh K; Khanna S; Sen CK; Roy S, Engulfment of Apoptotic Cells by Macrophages: A Role of MicroRNA-21 in the Resolution of Wound Inflammation. J. Immunol 2014, 192, 1120–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das A; Ghatak S; Sinha M; Chaffee S; Ahmed NS; Parinandi NL; Wohleb ES; Sheridan JF; Sen CK; Roy S, Correction of MFG-E8 Resolves Inflammation and Promotes Cutaneous Wound Healing in Diabetes. J. Immunol 2016, 196, 5089–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das A; Sinha M; Datta S; Abas M; Chaffee S; Sen CK; Roy S, Monocyte and Macrophage Plasticity in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Am. J. Pathol 2015, 185, 2596–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim DK; Lee J; Kim SR; Choi DS; Yoon YJ; Kim JH; Go G; Nhung D; Hong K; Jang SC; Kim SH; Park KS; Kim OY; Park HT; Seo JH; Aikawa E; Baj-Krzyworzeka M; van Balkom BW; Belting M; Blanc L; et al. EVpedia: A Community Web Portal for Extracellular Vesicles Research. Bioinformatics. 2015, 31, 933–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keerthikumar S; Chisanga D; Ariyaratne D; Al Saffar H; Anand S; Zhao K; Samuel M; Pathan M; Jois M; Chilamkurti N; Gangoda L; Mathivanan S, ExoCarta: A Web-Based Compendium of Exosomal Cargo. J. Mol. Biol 2016, 428, 688–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreu Z; Yáñez-Mó M, Tetraspanins in Extracellular Vesicle Formation and Function. Front. Immunol 2014, 5, 442–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Deun J; Mestdagh P; Agostinis P; Akay O; Anand S; Anckaert J; Martinez ZA; Baetens T; Beghein E; Bertier L; Berx G; Boere J; Boukouris S; Bremer M; Buschmann D; Byrd JB; Casert C; Cheng L; Cmoch A; Daveloose D et al. EV-TRACK: Transparent REporting and Centralizing Knowledge in Extracellular Vesicle Research. Nat. Methods. 2017, 14, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Deun J; Hendrix A; consortium E-T, Is Your Article EV-TRACKed? J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2017, 6, 1379835–1379835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu P; Yang Q; Wang Q; Shi C; Wang D; Armato U; Prà ID; Chiarini A, Mesenchymal Stromal Cells-Exosomes: A Promising Cell-Free Therapeutic Tool For Wound Healing and Cutaneous Regeneration. Burns Trauma. 2019, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He X; Dong Z; Cao Y; Wang H; Liu S; Liao L; Jin Y; Yuan L; Li B, MSC-Derived Exosome Promotes M2 Polarization and Enhances Cutaneous Wound Healing. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019, 7132708–7132708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallego-Perez D; Pal D; Ghatak S; Malkoc V; Higuita-Castro N; Gnyawali S; Chang L; Liao WC; Shi J; Sinha M; Singh K; Steen E; Sunyecz A; Stewart R; Moore J; Ziebro T; Northcutt RG; Homsy M; Bertani P; Lu W; et al. Topical Tissue Nano-Transfection Mediates Non-Viral Stroma Reprogramming and Rescue. Nat. Nanotechnol 2017, 12, 974–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guasconi L; Serradell MC; Garro AP; Iacobelli L; Masih DT, C-Type Lectins on Macrophages Participate in the Immunomodulatory Response to Fasciola Hepatica Products. Immunology. 2011, 133, 386–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drickamer K, Engineering Galactose-Binding Activity into a C-Type Mannose-Binding Protein. Nature. 1992, 360, 183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Pomares L; Linehan SA; Taylor PR; Gordon S, Binding Properties of the Mannose Receptor. Immunobiology. 2001, 204, 527–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song W; Zhou X; Benktander JD; Gaunitz S; Zou G; Wang Z; Novotny MV; Jacobson SC, In-Depth Compositional and Structural Characterization of N-Glycans Derived from Human Urinary Exosomes. Anal. Chem 2019, 91, 13528–13537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder CM; Zhou X; Karty JA; Fonslow BR; Novotny MV; Jacobson SC, Capillary Electrophoresis-Mass Spectrometry for Direct Structural Identification of Serum N-Glycans. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1523, 127–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clerc F; Reiding KR; Jansen BC; Kammeijer GS; Bondt A; Wuhrer M, Human Plasma Protein N-Glycosylation. Glycoconj. J 2016, 33, 309–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brancato SK; Albina JE, Wound Macrophages as Key Regulators of Repair: Origin, Phenotype, and Function. Am. J. Pathol 2011, 178, 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mirza RE; Koh TJ, Contributions of Cell Subsets to Cytokine Production During Normal and Impaired Wound Healing. Cytokine. 2015, 71, 409–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray PJ; Allen JE; Biswas SK; Fisher EA; Gilroy DW; Goerdt S; Gordon S; Hamilton JA; Ivashkiv LB; Lawrence T; Locati M; Mantovani A; Martinez FO; Mege J-L; Mosser DM; Natoli G; Saeij JP; Schultze JL; Shirey KA; Sica A; et al. Macrophage Activation and Polarization: Nomenclature and Experimental Guidelines. Immunity. 2014, 41, 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El Masry MS; Chaffee S; Das Ghatak P; Mathew-Steiner SS; Das A; Higuita-Castro N; Roy S; Anani RA; Sen CK, Stabilized Collagen Matrix Dressing Improves Wound Macrophage Function and Epithelialization. FASEB J 2019, 33, 2144–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosser DM; Edwards JP, Exploring the Full Spectrum of Macrophage Activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2008, 8, 958–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J; Ghatak S; El Masry MS; Das A; Liu Y; Roy S; Lee RJ; Sen CK, Topical Lyophilized Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles in the Restoration of Skin Barrier Function Following Burn Wound. Mol. Ther 2018, 26, 2178–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulkarni J; Cullis P; van der Meel R, Lipid Nanoparticles Enabling Gene Therapies: From Concepts to Clinical Utility. Nucleic Acid Ther 2018, 28, 146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rietwyk S; Peer D, Next-Generation Lipids in RNA Interference Therapeutics. ACS nano. 2017, 11, 7572–7586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jayaraman M; Ansell SM; Mui BL; Tam YK; Chen J; Du X; Butler D; Eltepu L; Matsuda S; Narayanannair JK, Maximizing the Potency of siRNA Lipid Nanoparticles for Hepatic Gene Silencing In Vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 8529–8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barki KG; Das A; Dixith S; Ghatak PD; Mathew-Steiner S; Schwab E; Khanna S; Wozniak DJ; Roy S; Sen CK, Electric Field Based Dressing Disrupts Mixed-Species Bacterial Biofilm Infection and Restores Functional Wound Healing. Ann. Surg 2019, 269, 756–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy S; Elgharably H; Sinha M; Ganesh K; Chaney S; Mann E; Miller C; Khanna S; Bergdall VK; Powell HM; Cook CH; Gordillo GM; Wozniak DJ; Sen CK, Mixed-Species Biofilm Compromises Wound Healing by Disrupting Epidermal Barrier Function. J. Pathol 2014, 233, 331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghatak S; Chan YC; Khanna S; Banerjee J; Weist J; Roy S; Sen CK, Barrier Function of the Repaired Skin Is Disrupted Following Arrest of Dicer in Keratinocytes. Mol. Ther 2015, 23, 1201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nithya S; Radhika T; Jeddy N, Loricrin - An Overview. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol 2015, 19, 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalinin A; Marekov LN; Steinert PM, Assembly of the Epidermal Cornified Cell Envelope. J. Cell Sci 2001, 114, 3069–3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sen CK; Khanna S; Babior BM; Hunt TK; Ellison EC; Roy S, Oxidant-Induced Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression in Human Keratinocytes and Cutaneous Wound Healing. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 33284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan YC; Khanna S; Roy S; Sen CK, miR-200b Targets Ets-1 and Is Down-Regulated by Hypoxia to Induce Angiogenic Response of Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 2047–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Das A; Abas M; Biswas N; Banerjee P; Ghosh N; Rawat A; Khanna S; Roy S; Sen CK, A Modified Collagen Dressing Induces Transition of Inflammatory to Reparative Phenotype of Wound Macrophages. Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 14293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]