Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Is IVF with frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer (freeze-all strategy) more effective than IVF with fresh and frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer (conventional strategy)?

SUMMARY ANSWER

The freeze-all strategy was inferior to the conventional strategy in terms of cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate per woman.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

IVF without transfer of fresh embryos, thus with frozen-thawed embryo transfer only (freeze-all strategy), is increasingly being used in clinical practice because of a presumed benefit. It is still unknown whether this new IVF strategy increases IVF efficacy.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

A single-centre, open label, two arm, parallel group, randomised controlled superiority trial was conducted. The trial was conducted between January 2013 and July 2015 in the Netherlands. The intervention was one IVF cycle with frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer(s) versus one IVF cycle with fresh and frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer(s). The primary outcome was cumulative ongoing pregnancy resulting from one IVF cycle within 12 months after randomisation. Couples were allocated in a 1:1 ratio to the freeze-all strategy or the conventional strategy with an online randomisation programme just before the start of down-regulation.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Participants were subfertile couples with any indication for IVF undergoing their first IVF cycle, with a female age between 18 and 43 years. Differences in cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates were expressed as relative risks (RR) with 95% CI. All outcomes were analysed following the intention-to-treat principle.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Two-hundred-and-five couples were randomly assigned to the freeze-all strategy (n = 102) or to the conventional strategy (n = 102). The cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate per woman was significantly lower in women allocated to the freeze-all strategy (19/102 (19%)) compared to women allocated to the conventional strategy (32/102 (31%); RR 0.59; 95% CI 0.36–0.98).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

As this was a single-centre study, we were unable to study differences in study protocols and clinic performance. This, and the limited sample size, should make one cautious in using the results as the basis for definitive policy. All patients undergoing IVF, including those with a poor prognosis, were included; therefore, the outcome could differ in women with a good prognosis of IVF treatment success.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Our results indicate that there might be no benefit of a freeze-all strategy in terms of cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates. The efficacy of the freeze-all strategy in subgroups of patients, different stages of embryo development, and different freezing protocols needs to be further established and balanced against potential benefits and harms for mothers and children.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW grant 171101007). S.M., F.M. and M.v.W. stated they are authors of the Cochrane review ‘Fresh versus frozen embryo transfers in assisted reproduction’.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

Dutch Trial Register, NTR3187

TRIAL REGISTRATION DATE

9 December 2011

DATE OF FIRST PATIENT’S ENROLMENT

8 January 2013

Keywords: IVF, ICSI, freeze all, embryo transfer, cryopreservation, endometrium, randomised controlled trial

Introduction

IVF without fresh embryo transfer, thus with frozen-thawed embryo transfer only (freeze-all strategy), is increasingly being used in clinical practice in women undergoing IVF in an attempt to increase their chances of a pregnancy (Barnhart, 2014). The underlying rationale is to avoid possible side effects of ovarian stimulation on endometrial receptivity during the initial treatment cycle by postponing embryo transfer to a subsequent cycle without ovarian stimulation (Mastenbroek et al., 2011; Maheshwari and Bhattacharya, 2013; Wong et al., 2014). In women at risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), the freeze-all strategy has been applied for years, but with the aim to prevent OHSS (Amso et al., 1989; Pattinson et al.,1994; Shaker et al., 1996; DeVroey et al. 2011).

Thus far, six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have compared cumulative live birth rates between a freeze-all strategy and a conventional strategy in women with a high risk of OHSS (Ferraretti et al., 1999), in good prognosis women based on the number of follicles (Shapiro et al., 2011a, 2011b), in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (Chen et al., 2016), and in young women without PCOS (Vuong et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2019). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of these studies showed that there was no difference between the strategies in cumulative live birth rate, i.e. the proportion of women achieving a live birth following the transfer of fresh or frozen embryos from one single cycle with ovarian stimulation (Wong et al., 2017). The risk of OHSS for these groups of women was significantly lower in the freeze-all strategy (Wong et al., 2017).

Before the Wong et al. (2017) systematic review and the largest study included in this review (Chen et al., 2016) were available, we initiated a single-centre RCT comparing cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates per woman in a freeze-all strategy with frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer to a conventional strategy with fresh and frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer, as evidence of a benefit was lacking. In contrast to the other RCTs conducted thus far, we included subfertile couples with any IVF indication, independent of the number of follicles or available embryos.

Materials and methods

Participants

We conducted a single-centre, open label, two arm, parallel group, randomised controlled superiority trial between January 2013 and July 2015. Women between 18 and 43 years of age who were scheduled for their first IVF cycle and who had no previous failed IVF cycles, in either the Academic Medical Centre (AMC) or in the teaching hospital Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (OLVG) were eligible for inclusion. All laboratory procedures were carried out in the AMC; couples treated in the OLVG received ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval in the OLVG, and embryo transfer in the AMC. The use of this so-called transport-IVF is routine practice in the Netherlands. The protocol involves shipment of the follicular fluids immediately after oocyte retrieval in a controlled environment at 37°C to the IVF laboratory in the collaborating hospital. Data over the years show no difference in terms of pregnancy rates between transport-IVF centres and centres in which oocytes are not transported. Couples undergoing a preimplantation genetic diagnosis cycle or undergoing a modified natural cycle were not included, as were couples with an HIV, hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection since all these cycles required modified IVF protocols. The study protocol was approved by the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects in the Netherlands. The institutional review boards of the AMC and of the OLVG provided local approval. All couples in this trial provided written informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

We randomised women with an online randomisation programme during their visit to plan the first IVF cycle, just before the start of down-regulation, using block randomisation with a maximum block size of six, stratified for age (18 years through 35 and 35 through 43 years), and study centre (AMC or OLVG). Couples were allocated in a 1:1 ratio to the freeze-all strategy or the conventional strategy. The randomisation programme generated a unique study number with allocation code after entry of the patient’s date of birth and randomisation date. The gynaecologists, embryologists and the researchers who analysed the data could not access the randomisation sequence. Blinding of couples, clinicians and embryologists was not possible due to the nature of the comparison under study.

IVF protocol

Pituitary down-regulation was achieved with a long GnRH agonist protocol with or without oral contraceptive pill (OCP) pre-treatment. Ovarian stimulation was conducted with hMG (Menopur, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Hoofddorp, the Netherlands) or recombinant FSH (follitropine, Puregon, Merck Sharp & Dohme BV, Haarlem, the Netherlands or Gonal-F, Merck, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) in women with PCOS starting from the seventh day without OCP. The starting dose depended on the antral follicle count (AFC) (van Tilborg et al., 2012). Ovulation was triggered with 5000 or 10 000 IU hCG (Pregnyl, Merck Sharp & Dohme BV, Haarlem, the Netherlands). We adhered to a single embryo transfer policy for women below 38 years of age and a double embryo transfer policy for women of 38 years of age and above, if two or more embryos were available.

Conventional strategy

We transferred embryos at Day 5 of culture. The morphologically best embryo(s) was transferred first. All surplus embryos were cryopreserved on Day 6 of culture. Women with a fresh transfer had luteal support with 600 mg vaginal micronized utrogestan (Utrogestan Besins Healthcare, Utrecht, the Netherlands) and continued this until the pregnancy test, 14 days after the fresh transfer. If not pregnant, frozen embryo transfer was scheduled in artificial cycles with oral estrogen (Progynova, Bayer B.V., Mijdrecht, the Netherlands) and vaginal micronized progesterone supplementation (Utrogestan Besins Healthcare, Utrecht, the Netherlands). If the endometrium had reached 8 mm on vaginal ultrasound, women started vaginal micronized progesterone (Utrogestan Besins Healthcare, Utrecht, the Netherlands) and thawing and transfer were scheduled. Women continued estrogen and progesterone supplementation until 11 + 5 weeks gestation. If not pregnant, a subsequent artificial cycle was started.

Freeze-all strategy

Embryos were cryopreserved on Day 6 of culture. After oocyte retrieval, women waited for their menstruation and started an artificial cycle with oral estrogen (Progynova, Bayer B.V., Mijdrecht, the Netherlands) and vaginal micronized progesterone supplementation (Utrogestan Besins Healthcare, Utrecht, the Netherlands), similar to the frozen embryo transfer in the conventional strategy. If not pregnant, a subsequent artificial cycle was started.

See Supplementary methods for details of the IVF protocol, including embryo culture, embryo grading and details on the artificial frozen embryo transfer cycle.

End of study

End of study was the achievement of an ongoing pregnancy, transfer of all embryos derived from the first oocyte retrieval within 12 months, or being 12 months after randomisation regardless of any remaining supernumerary cryopreserved embryos. A pregnancy test was performed on serum 2 weeks after blastocyst transfer and we considered a serum hCG >2 IU/L as positive. We confirmed clinical and ongoing pregnancies by ultrasonography at 7 and 12 weeks of gestation, respectively. If the ultrasound at 12 weeks of gestation was not performed in the participating centres, and if data on live births were missing, we contacted the couples by phone or postal mail to obtain data.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was cumulative ongoing pregnancy per woman after one cycle (Braakhekke et al., 2014). An ongoing pregnancy was defined as visible foetal cardiac activity at ultrasound from 12 weeks of gestation onwards, or a pregnancy that resulted in a live birth. Secondary outcomes were time to pregnancy defined as the time to ongoing pregnancy from the date of randomisation to the date of embryo transfer that led to an ongoing pregnancy, live birth defined as the delivery of a live foetus at ≥20 weeks of gestation, clinical pregnancy defined as the presence of at least one intrauterine gestational sac at 7 weeks of gestation, and biochemical pregnancy defined as serum hCG >2 IU/l. Safety outcomes were OHSS, multiple pregnancy, premature birth and congenital abnormalities. We also report on miscarriage rate, ectopic pregnancy rate and birthweight of the children born.

Sample size

The cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate per started cycle among women in the two centres after one cycle of IVF was ∼20% at the time of designing the study (NVOG, 2011). The null hypothesis assumed no difference while the alternative hypothesis assumed that pregnancy rates after the freeze-all strategy would be higher than after the conventional strategy. We expected a cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate after one cycle of 40% in the freeze-all strategy and of 20% in the conventional group. In a superiority design with a 5% significance level, 80% power and a two-sided test, we needed 164 evaluable couples. To account for a 15% loss to follow-up, we planned to include 193 couples.

Statistical analysis

Analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle. We assessed the primary outcome cumulative ongoing pregnancy per randomised woman. Natural conceptions that occurred after randomisation but before IVF treatment or between frozen-thawed embryo cycles were included in the analysis of the primary outcome. If women had an ongoing pregnancy from an embryo derived from the first cycle but transferred beyond 12 months after randomisation, these pregnancies were registered but not included in the analysis as primary outcome. We estimated differences in the binary outcomes as relative risks (RR) with 95% CI. The Chi-square test was used for categorical data, as appropriate. For continuous outcomes, we calculated mean and SD or median with range, and we evaluated differences using ANOVA or Mann–Whitney U tests, where appropriate. We constructed Kaplan–Meier curves to estimate the cumulative probability of an ongoing pregnancy over time and we analysed differences between the Kaplan–Meier curves with the log-rank test for significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 21.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). We considered P-values <0.05 statistically significant.

Results

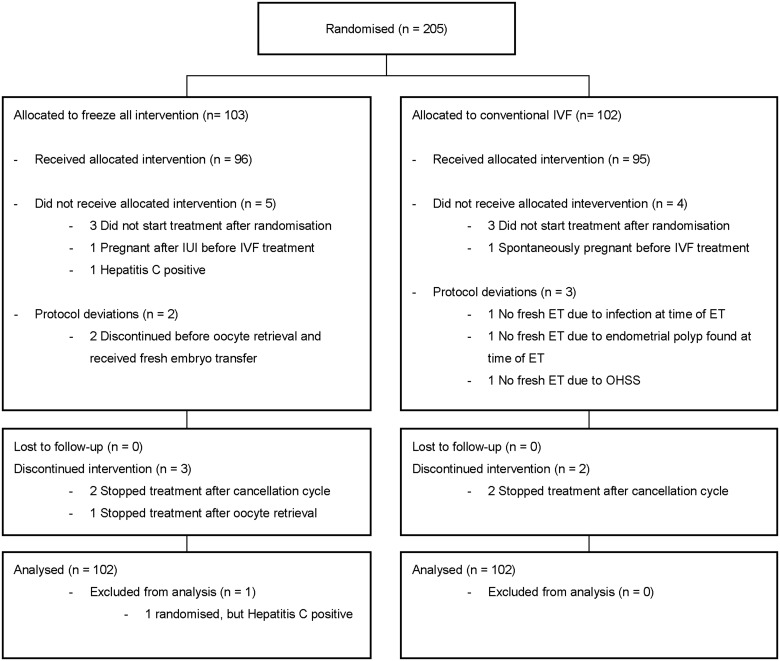

Between January 2013 and July 2015, 205 couples were randomly assigned: 103 couples allocated to the freeze-all strategy and 102 couples to the conventional strategy (Fig. 1). The reasons for not completing one cycle were similar between strategies and were primarily owing to personal reasons of the couple. One woman was randomised although she fulfilled one of the exclusion criteria. We excluded this woman from the analyses. In total, 204 couples were included in the analysis. Follow-up ended in July 2016. The baseline characteristics were similar between the two strategies (Table I).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. ET, embryo transfer; OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. All couples that did not start treatment or discontinued intervention were because of personal reasons.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the included couples in a randomised controlled trial of fresh or frozen embryo transfer.

| Freeze all | Conventional | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Women randomised (n) | 102 | 102 | |

| Treatment centre | |||

| AMC | 72 | 72 | |

| OLVG | 30 | 30 | |

| Maternal age (year) | 35.2 ± 4.7 | 35.1 ± 4.5 | |

| Paternal age (year) | 37.5 ± 6.2 | 38.6 ± 7.5 | |

| Duration of subfertility (year) | 3.0 ± 2.1 | 3.2 ± 2.4 | |

| Primary diagnosis of subfertility | |||

| Tuba factor | 10 (10) | 11(11) | |

| Anovulation | 2 (2) | 3(3) | |

| Endometriosis | 1 (1) | 1(1) | |

| Cervix factor | 1 (1) | 0(0) | |

| Male subfertility | 56 (55) | 54 (53) | |

| Unexplained | 28 (28) | 25 (25) | |

| Mixed female and male factor | 4 (4) | 8 (8) | |

| Sperm donor | |||

| Yes | 10 (10) | 5 (5) | |

| No | 92 (90) | 96 (95) | |

| Parity | 0.22 ± 0.6 | 0.27 ± 0.6 | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 16 (16) | 16 (16) | |

| No | 81 (79) | 79(77) | |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Intermediate vocational education | 23 (23) | 33 (32) | |

| Higher general education | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | |

| Higher education/university | 56 (55) | 42 (41) | |

| Not reported | 18 (18) | 20 (20) | |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6 ± 3.6 | 25.1 ± 5.0 | |

| Antral follicles | 9.4 ± 6.8 | 11.6 ± 8.9 |

AMC, Academic Medical Centre; OLVG, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis. Data presented as means ± SD or number (%)

Outcomes

Cumulative ongoing pregnancy was achieved in 19 couples (19%) in the freeze-all strategy and in 32 couples (31%) in the conventional strategy leading to an RR of 0.59 (95% CI 0.36–0.98) (Table II). The cumulative live birth rate (RR 0.62; 95% CI 0.34–1.04) between the two strategies was not significantly different. The cumulative clinical pregnancy rate (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.36–0.95) and the cumulative biochemical pregnancy rate (RR 0.6; 95%CI 0.38–0.87) between the strategies were significantly lower in the freeze-all strategy. After the first embryo transfer, ongoing pregnancy (RR 0.32; 95% CI 0.15–0.68), live birth (RR 0.32; 95% CI 0.14–0.71), clinical pregnancy (RR 0.35; 95% CI 0.17–0.71) and biochemical pregnancy rates (RR 0.43; 95% CI 0.25–0.74) were significantly lower in the freeze-all strategy. In subsequent embryo transfers, the RR for the freeze-all strategy versus the conventional strategy was 2.00 (95% CI 0.71–5.65) for ongoing pregnancy, 2.00 (95% CI 0.71–5.65) for live birth, 2.00 (95% CI 0.71–5.65) for clinical pregnancy and 1.11 (95% CI 0.47–2.62) for biochemical pregnancy.

Table II.

Effectiveness of the embryo transfer strategies: pregnancy outcomes.

| Freeze all (n = 102) |

Conventional

(n = 102) |

Relative risk | 95% CI | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ongoing pregnancy (a) | Cumulative | 19(19) | 32 (31) | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.036* |

| First ET | 8 (8) | 25 (25) | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.68 | 0.001* | |

| Subsequent ETs | 10 (10) | 5(5) | 2.00 | 0.71 | 5.65 | 0.180 | |

| Live birth (b) | Cumulative | 18 (18) | 29 (28) | 0.62 | 0.37 | 1.04 | 0.067 |

| First ET | 7 (7) | 22 (22) | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.71 | 0.003* | |

| Subsequent ETs | 10 (10) | 5 (5) | 2.00 | 0.71 | 5.65 | 0.180 | |

| Clinical pregnancy | Cumulative | 19 (19) | 33 (33) | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.95 | 0.027* |

| First ET | 9 (9) | 26 (25) | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.71 | 0.002* | |

| Subsequent ETs | 10 (10) | 5 (5) | 2.00 | 0.71 | 5.65 | 0.180 | |

| Biochemical pregnancy | Cumulative | 24 (24) | 42 (41) | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.87 | 0.007* |

| First ET | 15 (15) | 35 (34) | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.74 | 0.001* | |

| Subsequent ETs | 10 (10) | 9 (9) | 1.11 | 0.47 | 2.62 | 0.810 |

Data presented as number (%).

In the freeze-all strategy, one woman underwent elective termination of a pregnancy at 22 weeks of gestation because of trisomy 21.

In the conventional strategy, one woman terminated the gestation because of a cervical pregnancy and two women had spontaneous miscarriages at 14 and 16 weeks of gestation.

Cumulative pregnancy rates include pregnancies without IVF.

Not all couples who achieved ongoing pregnancy ended in a live birth.

P-value < 0.05. ET, embryo transfer.

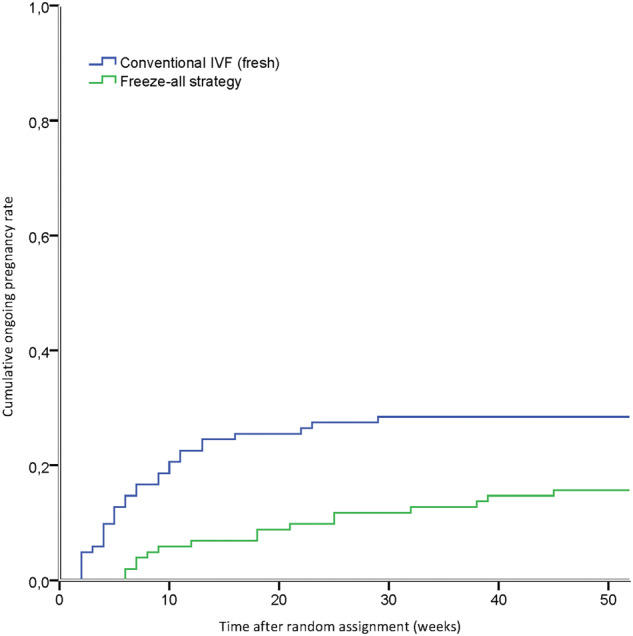

The time to ongoing pregnancy was significantly higher in the freeze-all strategy (46.9 weeks versus 39.6 weeks, log-rank P = 0.02; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Time to ongoing pregnancy. Ongoing pregnancies resulting from one IVF cycle within 12 months after randomisation. Time to ongoing pregnancy was calculated in weeks from date of randomisation to date of embryo transfer leading to an ongoing pregnancy. Log-rank P = 0.02, χ2 = 5.45, df (1). Freeze-all strategy.

Additional secondary outcomes are shown in Table III. No woman developed OHSS in the freeze-all strategy and three women developed OHSS in the conventional strategy. There was no significant difference in miscarriage rate between the freeze-all and conventional strategy. None of the women had an ectopic pregnancy in the freeze-all strategy and one woman had an ectopic pregnancy, i.e. cervical pregnancy, in the conventional strategy. None of the women had a multiple pregnancy in the freeze-all strategy and three women had a multiple pregnancy in the conventional strategy. There was no difference between the two strategies in birthweights after the first embryo transfer (P = 0.29) or subsequent embryo transfers (P = 0.91). In addition, there were no differences in the total birthweights lower than 2500 g and in preterm births before a gestational age of 37 weeks between the strategies. Congenital abnormalities did not occur in either group.

Table III.

Secondary outcomes of the randomised controlled trial.

| Freeze all | Conventional | Relative risk | 95% CI | P -value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 102) | (n = 102) | ||||||

| OHSS (a) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | |||||

| Miscarriage (b) | Cumulative | 14 (14) | 20 (20) | ||||

| First ET | 10 (10) | 16 (16) | 0.63 | 0.30 | 1.31 | 0.21 | |

| Subsequent ETs | 4 (4) | 6 (6) | 0.67 | 0.19 | 2.29 | 0.52 | |

| Ectopic pregnancy (c) | 0 | 1 (1) | |||||

| Multiple pregnancy | Cumulative | 0 | 3 (3) | ||||

| First ET | 0 | 2 (2) | |||||

| Subsequent ETs | 0 | 1 (1) | |||||

| Birthweight (d) | Cumulative | 3528 (518) | 3283 (704) | 0.20 | |||

| First ET | 3561 (257) | 3249 (743) | 0.29 | ||||

| Subsequent ETs | 3479 (672) | 3440 (579) | 0.91 | ||||

| Birthweight | <2500 g | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | ||||

| Preterm birth | <37 week | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | ||||

| Congenital abnormalities | 0 | 0 | |||||

Data presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) that required hospitalisation.

All miscarriages occurred before 20 weeks of gestation.

One woman had a cervical pregnancy.

Data of the first ET include two twin live borns, data in the subsequent ETs include one twin live born, both in the conventional group.

ET, embryo transfer.

Treatment and embryological characteristics

The treatment characteristics were similar between the strategies, with exception of the endometrium thickness, which was significantly thinner in the freeze-all strategy than in the conventional strategy (9.1 ± 2.1 versus 10.9 ± 2.7; P < 0.0001: Supplementary Table SI). The cumulative embryo implantation rate per woman (resulting in a gestational sac) was significantly lower in the freeze-all strategy than in the conventional strategy (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.31–0.77). For the first embryo transfer, the implantation rate was significantly lower in the freeze-all strategy than in the conventional strategy (RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.13–0.51). For the subsequent embryo transfers, there was no significant difference in the implantation rate between the freeze-all strategy and the conventional strategy (RR 1.83; 95% CI 0.71–4.77) (Supplementary Table SII).

Discussion

Our study suggests that a freeze-all strategy with transfer of frozen-thawed blastocysts significantly reduces cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate per woman after one cycle compared to a conventional strategy with transfer of fresh and frozen-thawed blastocysts in a general IVF population where all patients undergoing IVF, including those with a poor prognosis, were included. There was also evidence of reduced cumulative live birth, and significantly reduced cumulative clinical pregnancy, and cumulative biochemical pregnancy.

When comparing our results to other studies, we cannot compare our findings with RCTs that only reported ongoing pregnancy or live birth after the first transfer (Aghahosseini et al., 2017; Coates et al., 2017; Aflatoonian et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2018). However, in comparison to other RCTs that reported cumulative results, the success rate in the freeze-all strategy with frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer seems lower in the present study (Ferraretti et al., 1999; Shapiro et al., 2011a, 2011b; Chen et al., 2016; Vuong et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2019). These other RCTs have shown comparable cumulative live birth and ongoing pregnancy rates in both arms (Cochrane systematic review of Wong et al. (2017)). In the freeze-all arm, our cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate was 19% compared to 50–70% in the other RCTs. The cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate of the conventional arm was also lower than found in other studies but the difference was less. There could be several explanations for these differences.

The RCTs performed by Ferraretti et al. (1999, n = 125) and Shapiro et al. (2011a, n = 122) included high responders, defined as women at risk for OHSS and as women with more than 15 antral follicles at baseline ultrasound, respectively. The other RCT performed by Shapiro et al. (2011b, n = 137) included normal responders, defined as women that had 8–15 antral follicles at baseline ultrasound that were expected to have a good response to ovarian stimulation. The study by Chen et al. (2016, n = 1508) included women with PCOS in their first IVF cycle with four or more oocytes available after oocyte retrieval. Two studies (Vuong et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2019) included a general, but younger, IVF population (mean age 32 and 28 years, respectively) where the study by Vuong had to have a minimum of one available high-grade embryo, and the study by Wei a minimum of at least four high-grade quality embryos available before a women would be randomly assigned to one of the two groups.

Our study consisted of an unselected population undergoing IVF, including (expected) poor responders. The selection criteria of normal and high responders or of young women used in previous studies may represent women with a relatively better prognosis and are therefore more likely to have one or more (good quality) blastocysts for transfer resulting in a pregnancy. An exploratory post-hoc analysis from our data in women with more than two top-quality embryos on Day 3 of culture, indeed shows that the cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates per woman are similar between the strategies in our study (freeze all 39% (14/36) versus conventional 42% (15/36), RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.53–1.63). This suggests that the results of our study are in line with the outcomes of previous RCTs when analysing a more comparable patient population (Wong et al., 2017). It also made clear that the majority of the included patients in our study (65% 132/204) did not have at least three top-quality embryos on Day 3 of culture, which could possibly be explained by the patient characteristics of an IVF population where expectant management for at least 12 months is promoted before IVF treatment is started.

Apart from differences in study population, several other factors were different between our trial and those previously conducted that could possibly explain the differences in results. First, the timing of randomisation differed; either after retrieval (Ferraretti et al.,1999; Shapiro et al., 2011a, 2011b; Chen et al., 2016, Vuong et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2019) or before retrieval (our study). Second, the timing of embryo cryopreservation; either at the two pronuclei stage (Ferraretti et al., 1999; Shapiro et al., 2011a, 2011b), the cleavage stage (Chen et al., 2016; Vuong et al., 2018) or the blastocyst stage (Wei et al., 2019) and our study on Day 6, compared to our fresh blastocyst transfer on Day 5. Third, the method of cryopreservation; either slow freezing (Ferraretti et al., 1999; Shapiro et al., 2011a, 2011b) or vitrification (Chen et al., 2016; Vuong et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2019, and our study). And fourth, the embryo developmental stage at transfer; cleavage stage (Ferraretti et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2016; Vuong et al., 2018), morula or blastocyst stage (our study) or blastocyst stage only (Shapiro et al., 2011a, 2011b; Wei et al., 2019). Although the single-centre design did not allow for analyses considering differences in study protocols and clinical performance, one could speculate that our vitrification-thawing programme might have underperformed. However, based on the high survival rates of embryos after thawing in this study (96%, Supplementary Table SII), we conclude that we performed our vitrification-thawing correctly and that the frozen-thawed embryos were viable and were not affected in their morphological development by freezing. However, we cannot exclude possible damage in frozen-thawed embryos as a result of the vitrification procedure that cannot be determined by morphological development. Since we used fixed criteria, i.e. morulae and blastocysts, for embryo transfer and cryopreservation regardless of the developmental stage of embryos, this could have led to transfer and cryopreservation of embryos of suboptimal quality. We intentionally lowered the morphological cut-off criteria for cryopreservation by freezing embryos with identical morphologic criteria on Day 6 in the freeze-all strategy, and on Day 5 in the conventional strategy. We opted for this fixed transfer protocol, so embryos in the freeze-all strategy were not discarded that otherwise would have been transferred in the conventional strategy outside the RCT setting. Cryopreserving and later transferring slower developing embryos, i.e. morulae or early blastocysts, on Day 6 may be unfavourable for the freeze-all strategy when compared to the same embryo developmental stage, i.e. morulae or early blastocysts, on Day 5 in the conventional strategy. This could have caused a skewed comparison. In both study groups, multiple embryos were still cryopreserved at the end of the study (95 embryos in the freeze-all arm and 103 embryos in the conventional arm). We choose to set a limit on the time frame during which each included patient could remain in the study, in order to limit the duration of the study. The primary endpoint was achievement of an ongoing pregnancy, transfer of all embryos derived from the first oocyte retrieval within 12 months, or being 12 months after randomisation regardless of any remaining supernumerary cryopreserved embryos. The vast majority of the embryos that were still cryopreserved at the end of the study were from couples that achieved an ongoing pregnancy during the study, which seems to suggest that the chosen period did not affect the cumulative pregnancy rate in our study to a large extent as these women have already been counted as being pregnant. These embryos remain available to the couples should they request an additional child.

We used a fixed protocol for endometrium preparation regardless of the developmental stage of embryos and thus a possible mismatch in embryo development and endometrium development may have occurred. In general, the quality of the endometrium is difficult to determine, but seems an unlikely cause of the lower pregnancy rate in the freeze-all strategy since the endometrium was never thinner than 7 mm, a cut-off that has been related to a lower chance of pregnancy . In addition, we used an accepted common protocol for endometrium preparation for transfer of frozen-thawed embryos (Shapiro et al., 2014).

The decision to offer the freeze-all strategy should be balanced against potential benefit and harm for mother and child. It is known that the freeze-all strategy is associated with an increased risk of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and large for gestational age as well as a higher birthweight in singleton babies (Maheshwari et al., 2018). In conclusion, our findings suggest that a freeze-all strategy of blastocysts does not result in a better cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate in unselected couples undergoing IVF compared to a fresh transfer strategy.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Human Reproduction online.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Authors’ roles

K.M.W., M.v.W., S.R. and S.M. designed the trial. K.M.W., H.R.V. and S.R. coordinated the trial. K.M.W. collected the data. K.M.W., F.M. and M.v.W. analysed the data. K.M.W., F.M. and S.M. drafted the report. All authors interpreted the data, revised the report and approved the final submitted version.

Funding

The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW grant 171101007).

Conflict of interest

M.v.W., F.M. and S.M. are authors of the Cochrane review ‘Fresh versus frozen embryo transfers in assisted reproduction’.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods: Details of the interventions

Ovarian stimulation and follicle aspiration

Pituitary down-regulation was achieved with a long GnRH agonist protocol with or without oral contraceptive pill (OCP) pre-treatment.

OCP pre-treatment consisted of a second-generation OCP (30 μg ethinylestradiol and 150μg levonorgestrel) once daily for at least 14 days with start of the GnRH agonist (triptorelin, Decapeptyl, Ferring Pharmateuticals, Hoofddorp, the Netherlands) during the last three OCP days. Ovarian stimulation was conducted with hMG (Menopur, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Hoofddorp, the Netherlands) starting from the seventh day without OCP.

The long GnRH agonist protocol without OCP pre-treatment consisted of GnRH agonist starting in the mid-luteal phase of the cycle prior to ovarian stimulation. Ovarian stimulation was started with hMG (Menopur, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Hoofddorp, the Netherlands) from the third or fifth day of the start of the menstruation (cycle Days 3–5).

Women with PCOS received recombinant FSH (follitropine, Puregon, Merck Sharp & Dohme BV, Haarlem, the Netherlands or Gonal-F, Merck, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) instead of hMG to allow dose adjustment of recombinant FSH.

We measured the antral follicle count (AFC) between cycle Days 3 and 5 of the menstruation or withdrawal bleed after stopping the OCP during pituitary down-regulation. If the AFC was between 1 and 7, the initial dose was 450 IU, if the AFC was between 8 and 10, the dose was 225 IU and if the AFC was more than 10, the dose was 150 IU. This stimulation regime was based upon the experimental arm of a randomised controlled trial (OPTIMIST_NTR2657) that compared the effectiveness between an individualised stimulation regimen and a conventional stimulation regime. This trial was running at the time of designing our trial (van Tilborg et al., 2017). We continued ovarian stimulation until three or more follicles with a diameter of 18 mm had developed. In case of poor or hyper response, defined as less than 3 follicles or more than 20, respectively, we cancelled the cycle, but these women were offered an additional cycle and continued in the trial. We monitored endometrial thickness by transvaginal ultrasound scanning during ovarian stimulation and measured endometrial thickness as the maximal echogenic distance between the junction of the endometrium and myometrium in the mid-sagittal plane. We classified the endometrial pattern as A if the endometrium showed a homogenous, hyperechogenic pattern, as B if the endometrium showed an intermediate isoechogenic pattern with the same reflectivity as the surrounding myometrium and a poorly defined central echogenic line and as C if the endometrium showed a multi-layered pattern, also designated ‘triple-line’ pattern (Gonen and Casper, 1990). We aspirated follicles under transvaginal ultrasound guidance ∼36 h after ovulation induction with 5000 or 10 000 IU of hCG (Pregnyl, Merck Sharp & Dohme BV, Haarlem, the Netherlands). On the day of the hCG trigger, progesterone serum levels were measured (Enzyme labelled sandwich immunoassay, Roche Diagnostics Nederland BV, Almere, the Netherlands).

Embryo culture

In case of IVF, oocytes were placed in groups of four in 100-μl fertilisation medium (Quinn’s Advantage™ Fertilization Medium, Cooper Surgical Distribution BV, Venlo, the Netherlands) with a total of 10 000–15 000 progressively motile spermatozoa for fertilization. The next morning, all embryos were transferred to a new dish and cultured individually in 25 μl of pre-equilibrated cleavage medium (Quinn’s Advantage™ Cleavage Medium, Cooper Surgical Distribution BV, Venlo, the Netherlands). On Day 3 of culture, embryos were transferred to a new dish with blastocyst medium (Quinn’s Advantage™ Blastocyst Media, Cooper Surgical Distribution BV, Venlo, the Netherlands).

In case of ICSI, oocytes were denudated with cumulase (Origio Benelux BV, Venlo, the Netherlands), injected with a single immobilised spermatozoon ∼4 h after follicular aspiration, and directly thereafter, cultured in cleavage medium (Quinn’s Advantage™ Cleavage Medium, Cooper Surgical Distribution BV, Venlo, the Netherlands). Subsequent culture was identical between IVF and ICSI.

Culture media were covered with mineral oil (Oil for Embryo Culture, FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, Alere Health BV, Tilburg, the Netherlands). All embryos were cultured individually in standard incubators under 5% CO2 and 5% O2 atmosphere.

Embryo development and grading

We assessed embryo morphology daily. For cleavage stage embryos, we assessed cell number, the degree of fragmentation, which was defined as the presence of anuclear, membrane-bound extracellular cytoplasmic structures (0–10%, 10–20%, 20–50%, >50%) of the embryo, and the uniformity of the blastomeres in terms of equal or unequal size i.e. >25% difference in size of the blastomeres (Puissant et al., 1987). In morulae, we assessed the degree of compaction, which was defined as blastomeres that had begun to compact tightly, forming a clustered cell mass, and the percentage of fragmentation. In blastocysts, we assessed the inner cell mass, the trophectoderm cells and the size of expansion of the blastocoel according to the Gardner and Schoolcraft (1999) system.

Endometrial preparation

We transferred embryos in cycles with oral estrogen supplementation (Progynova, Bayer B.V., Mijdrecht, the Netherlands) and/or vaginal progesterone supplementation (Utrogestan Besins Healthcare, Utrecht, the Netherlands). In case of a frozen-thawed embryo transfer, women started with oral estrogen supplementation of 6 mg daily on the first day of their first vaginal bleeding after the follicular aspiration. After 14 days of oral estrogen supplementation, we performed an ultrasound to measure the endometrial thickness. If the endometrium had reached 8 mm, women started vaginal progesterone of 600 mg daily and continued the oral estrogen. If the endometrium was thinner than 8 mm at day 14, we increased the estrogen dose to 8 mg daily followed by a re-evaluation with ultrasound on Day 21 of estrogen supplementation. Then, if the endometrium had reached 8 mm or more, vaginal progesterone 600 mg daily was started and oral estrogen continued at the same dose. At the seventh day of vaginal progesterone administration, women had their frozen-thawed embryo transfer in the afternoon. Estrogen and progesterone supplementation was continued until the 11th week of gestation, if pregnancy occurred. In case of a fresh embryo transfer, women started with vaginal progesterone administration 600 mg daily on the day of the follicle aspiration, Day 0. On Day 5, after follicle aspiration i.e. the sixth day of vaginal progesterone administration women had their fresh embryo transfer. Progesterone supplementation was continued until the pregnancy test, 14 days after the fresh transfer.

Embryo transfer

We adhered to a single embryo transfer policy for women below 38 years of age and a double embryo transfer policy for women of 38 years of age and above, if two or more embryos were available. We selected only embryos that were at the morula or blastocyst stage for transfer and/or cryopreservation. In case of fresh transfer, we transferred embryos at Day 5 of culture. All embryos were cryopreserved on Day 6 of culture. In case thawed embryos were transferred, embryos were transferred on the same day of thawing.

Cryopreservation and thawing

We vitrified embryos on Day 6 of culture with the Cryotop method (Cryotop®, Kitazato Dibimed, Valencia, Spain) (Kuwayama et al., 2005; Kuwayama, 2007). For warming of the cryotop, we also applied the protocol as described by Kuwayama (2007). Depending on the transfer policy (single embryo transfer or double embryo transfer), we thawed embryos one by one or two by two. We thawed embryos with the best morphological scores first, evaluated the morphology of the embryo directly after thawing and performed a second evaluation 4 h later, just prior to embryo transfer.

References

- Aflatoonian A, Mansoori-Torshizi M, Farid Mojtahedi M, Aflatoonian B, Khalili MA, Amir-Arjmand MH, Soleimani M, Aflatoonian N, Oskouian H, Tabibnejad N. et al. Fresh versus frozen embryo transfer after gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist trigger in gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist cycles among high responder women: a randomized, multi-center study. Int J Reprod Biomed 2018;16:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghahosseini M, Aleyasin A, Sarfjoo FS, Mahdavi A, Yaraghi M, Saeedabadi H.. In vitro fertilization outcome in frozen versus fresh embryo transfer in women with elevated progesterone level on the day of HCG injection: an RCT. Int J Reprod Biomed 2017;15:757–762. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amso NN, Ahuia KK, Morris N, Shaw RW.. Elective preembryo cryopreservation in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. J Assist Reprod Genet 1989;6:312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart KT. Introduction: are we ready to eliminate the transfer of fresh embryos in in vitro fertilization? Fertil Steril 2014;102:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braakhekke M, , Kamphuis EI, , Dancet EA, , Mol F, , Van Der Veen F, , Mol BW. Ongoing pregnancy qualifies best as the primary outcome measure of choice in trials in reproductive medicine: an opinion paper. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1203–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z-J, Shi Y, Sun Y, Zhang B, Liang X, Cao Y, Yang J, Liu J, Wei D, Weng N. et al. Fresh versus frozen embryos for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2016;375:523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates A, Kung A, Mounts E, Hesla J, Bankowski B, Barbieri E, Ata B, Cohen J, Munné S.. Optimal euploid embryo transfer strategy, fresh versus frozen, after preimplantation genetic screening with next generation sequencing: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril 2017;107:723–730.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devroey P, Polyzos NP, Blockeel C.. An OHSS-free clinic by segmentation of IVF treatment. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2593–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraretti AP, Gianaroli L, Magli C, Fortini D, Selman HA, Feliciani E.. Elective cryopreservation of all pronucleate embryos in women at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: efficiency and safety. Hum Reprod 1999;14:1457–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Schoolcraft WB.. In-Vitro Culture of Human Blastocysts. Carnforth: Parthenon Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gonen Y, Casper RF.. Prediction of implantation by the sonographic appearance of the endometrium during controlled ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization (IVF). J Assist Reprod Genet 1990;7:146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama M. Highly efficient vitrification for cryopreservation of human oocytes and embryos: the Cryotop method. Theriogenology 2007;67:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama M, Vajta G, Ieda S, Kato O.. Comparison of open and closed methods for vitrification of human embryos and the elimination of potential contamination. Reprod Biomed Online 2005;11:608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S.. Elective frozen replacement cycles for all: ready for prime time? Hum Reprod 2013;28:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari A, Pandey S, Amalraj Raja E, Shetty A, Hamilton M, Bhattacharya S.. Is frozen embryo transfer better for mothers and babies? Can cumulative meta-analysis provide a definitive answer? Hum Reprod Update 2018;24:35–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastenbroek S, van der Veen F, Aflatoonian A, Shapiro B, Bossuyt P, Repping S.. Embryo selection in IVF. Hum Reprod 2011;26:964–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVOG. 2011. http://www.nvog.nl//Sites/Files/0000003049_IVF_cijfers_2011_per_kliniek.pdf

- Pattinson HA, Hignett M, Dunphy BC, Fleetham JA.. Outcome of thaw embryo transfer after cryopreservation of all embryos in patients at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 1994;62:1192–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puissant F, Van Rysselberge M, Barlow P, Deweze J, Leroy F.. Embryo scoring as a prognostic tool in IVF treatment. Hum Reprod 1987;2:705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker AG, Zosmer A, Dean N, Bekir JS, Jacobs HS, Tan SL.. Comparison of intravenous albumin and transfer of fresh embryos with cryopreservation of all embryos for subsequent transfer in prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 1996;65:992–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C, Thomas S.. Evidence of impaired endometrial receptivity after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized trial comparing fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfer in normal responders. Fertil Steril 2011a;96:344–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C, Thomas S.. Evidence of impaired endometrial receptivity after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized trial comparing fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfers in high responders. Fertil Steril 2011b;96:516–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D, Boostanfar R, Silverberg K, Yanushpolsky EH.. Examining the evidence: progesterone supplementation during fresh and frozen embryo transfer. Reprod Biomed Online 2014;29:S1–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Sun Y, Hao C, Zhang H, Wei D, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Deng X, Qi X, Li H. et al. Transfer of fresh versus frozen embryos in ovulatory women. N Engl J Med 2018;378:126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tilborg TC, Eijkemans MJ, Laven JS, Koks CA, de Bruin JP, Scheffer GJ, van Golde RJ, Fleischer K, Hoek A, Nap AW. et al. The OPTIMIST study: optimisation of cost effectiveness through individualised FSH stimulation dosages for IVF treatment. A randomised controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 2012;12:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tilborg TC, Oudshoorn SC, Eijkemans MJC, Mochtar MH, van Golde RJT, Hoek A, Kuchenbecker WKH, Fleischer K, de Bruin JP, Groen H. et al.; OPTIMIST Study Group. Individualized FSH dosing based on ovarian reserve testing in women starting IVF/ICSI: a multicentre trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Hum Reprod 2017;32:2485–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong LN, Dang VQ, Ho TM, Huynh BG, Ha DT, Pham TD, Nguyen LK, Norman RJ, Mol BW.. IVF transfer of fresh or frozen embryos in women without polycystic ovaries. N Engl J Med 2018;378:137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D, Liu J-Y, Sun Y, Shi Y, Zhang B, Liu J-Q, Tan J, Liang X, Cao Y, Wang Z. et al. Frozen versus fresh single blastocyst transfer in ovulatory women: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;393:1310–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KM, Mastenbroek S, Repping S.. Cryopreservation of human embryos and its contribution to in vitro fertilization success rates. Fertil Steril 2014;102:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KM, van Wely M, Mol F, Repping S, Mastenbroek S.. Fresh versus frozen embryo transfers in assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;28:CD011184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.