Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Do genetic variations in the DNA damage response pathway modify the adverse effect of alkylating agents on ovarian function in female childhood cancer survivors (CCS)?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Female CCS carrying a common BR serine/threonine kinase 1 (BRSK1) gene variant appear to be at 2.5-fold increased odds of reduced ovarian function after treatment with high doses of alkylating chemotherapy.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Female CCS show large inter-individual variability in the impact of DNA-damaging alkylating chemotherapy, given as treatment of childhood cancer, on adult ovarian function. Genetic variants in DNA repair genes affecting ovarian function might explain this variability.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

CCS for the discovery cohort were identified from the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG) LATER VEVO-study, a multi-centre retrospective cohort study evaluating fertility, ovarian reserve and risk of premature menopause among adult female 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. Female 5-year CCS, diagnosed with cancer and treated with chemotherapy before the age of 25 years, and aged 18 years or older at time of study were enrolled in the current study. Results from the discovery Dutch DCOG-LATER VEVO cohort (n = 285) were validated in the pan-European PanCareLIFE (n = 465) and the USA-based St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (n = 391).

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

To evaluate ovarian function, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels were assessed in both the discovery cohort and the replication cohorts. Using additive genetic models in linear and logistic regression, five genetic variants involved in DNA damage response were analysed in relation to cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED) score and their impact on ovarian function. Results were then examined using fixed-effect meta-analysis.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Meta-analysis across the three independent cohorts showed a significant interaction effect (P = 3.0 × 10−4) between rs11668344 of BRSK1 (allele frequency = 0.34) among CCS treated with high-dose alkylating agents (CED score ≥8000 mg/m2), resulting in a 2.5-fold increased odds of a reduced ovarian function (lowest AMH tertile) for CCS carrying one G allele compared to CCS without this allele (odds ratio genotype AA: 2.01 vs AG: 5.00).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

While low AMH levels can also identify poor responders in assisted reproductive technology, it needs to be emphasized that AMH remains a surrogate marker of ovarian function.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Further research, validating our findings and identifying additional risk-contributing genetic variants, may enable individualized counselling regarding treatment-related risks and necessity of fertility preservation procedures in girls with cancer.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This work was supported by the PanCareLIFE project that has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 602030. In addition, the DCOG-LATER VEVO study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant no. VU 2006-3622) and by the Children Cancer Free Foundation (Project no. 20) and the St Jude Lifetime cohort study by NCI U01 CA195547. The authors declare no competing interests.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: ovarian reserve, childhood cancer, survivorship, fertility, gonadotoxicity

Introduction

Advances in childhood cancer treatment have increased cancer survival rates leading to a growing population of childhood cancer survivors (CCS) (Trama et al., 2016). Abdominal-pelvic radiotherapy and alkylating agents may compromise ovarian function (Green et al., 2009; Overbeek et al., 2017; van der Kooi et al., 2017) and reduce survivors’ reproductive window. This may manifest as sub- or infertility (Chow et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2018) and a higher risk of premature menopause (Levine et al., 2018), which in turn may impair quality of life (Langeveld et al., 2004; van den Berg et al., 2007; Duffy and Allen, 2009; Carter et al., 2010; Zebrack et al., 2013; van der Kooi et al., 2019a). Substantial inter-individual variability in the impact of treatment on ovarian function in similarly treated CCS suggests a role for genetic factors in modifying the association between treatment and the risk of ovarian impairment.

Large-scale genome wide association studies (GWAS) in the general population have identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with age at natural menopause or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) (Perry et al., 2009; Stolk et al., 2009; He et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2013; Day et al., 2015, 2017). These SNPs include variants associated with the DNA damage response (Perry et al., 2013). Alkylating agents, common chemotherapeutic agents used in childhood cancer treatment, induce apoptosis of cancer cells by damaging DNA and inhibiting cellular metabolisms, DNA replication and transcription (Guainazzi and Schärer, 2010; Kondo et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2012). We hypothesized that girls and young women with less efficient DNA damage response systems are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of alkylating agents leading to ovarian dysfunction later in life compared to women with a fully efficient DNA damage repair system.

Serum levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), produced by the granulosa cells of small growing follicles in the ovaries, are related to age at onset of menopause in healthy women (van Disseldorp et al., 2008) and can detect ovarian dysfunction prior to both detectible changes in FSH/LH or oestrogen and clinical manifestations of menopause (van Beek et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 2012; Dewailly et al., 2014). In addition, AMH has been demonstrated as a useful and early surrogate marker of reduced ovarian function in cancer survivors (van Beek et al., 2007; Lie et al., 2009; Charpentier et al., 2014; Lunsford et al., 2014; van den Berg et al., 2018; van der Kooi et al., 2019b).

Identifying genetic risk factors for treatment-related reduced ovarian function may have clinical implications for risk assessment and medical decision-making regarding fertility preservation in newly diagnosed girls with cancer (van den Heuvel-Eibrink et al., 2018). The aim of the current study was, therefore, to evaluate whether SNPs in the DNA damage response pathway modify the adverse effect of alkylating agents on ovarian function in CCS.

Materials and methods

Study participants—discovery cohort

CCS for the discovery cohort were identified from the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG) LATER VEVO-study, a multi-centre retrospective cohort study evaluating fertility, ovarian reserve and risk of premature menopause among adult female 5-year survivors of childhood cancer (Overbeek et al., 2012). Data on prior cancer diagnoses and treatments were collected from medical files and information on use of hormones (contraceptives or hormonal replacement therapy) and menopausal status at time of study was obtained from the DCOG LATER VEVO-study questionnaire (Overbeek et al., 2012). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee (IRB protocol number 2006/249, VUmc) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Female 5-year CCS, diagnosed with cancer and treated with chemotherapy before the age of 25 years, and aged 18 years or older at time of study were enrolled in the current study. Eligible participants provided a blood sample to quantify AMH levels and extract DNA. Some types of treatment are known to have an invariably extremely detrimental effect on ovarian function. Effects can be so absolute, that this leaves little room for inter-individual variance of the chosen phenotype, as a result of genetic susceptibility. To maximize the potential to detect a role of genetic variation, we excluded survivors who received treatments associated with extensive gonadal toxicity including allogeneic stem cell transplantation, total body irradiation, bilateral ovary-exposing radiotherapy, cranial and/or craniospinal radiotherapy, or bilateral oophorectomy.

Study participants—replication cohorts

PanCareLIFE cohort

PanCareLIFE is a pan-European research project including 28 institutions from 13 countries addressing ototoxicity, fertility and quality of life (Byrne et al., 2018). This cohort included all adult 5-year female survivors from the PanCareLIFE cohort who were treated for cancer before the age of 25 years and fulfilled all inclusion criteria of this study (van der Kooi et al., 2018). Demographic, disease- and treatment-related data were collected from medical record files. Approval was obtained from all relevant local review boards and written informed consent from all participants.

St. Jude lifetime cohort

The St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE) is a cohort study among 10-year CCS in North America coordinated by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Memphis, TN, USA) combining treatment data, patient-reported outcomes and clinical assessment (Hudson et al., 2017). Participants in SJLIFE who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and had blood samples available for AMH and DNA analysis comprised the second replication cohort. Sex hormone use at time of study was documented.

Outcome and outcome definition

The outcome of this study was ovarian function, primarily determined by serum levels of AMH. AMH levels of all three cohorts were determined in the endocrine laboratory of the Free University (VU) Medical Center Amsterdam by an ultra-sensitive Elecsys AMH assay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) with an intra-assay coefficient of variation of 0.5–1.8%, a limit of detection (LoD) of 0.01 µg/l, and a limit of quantitation (LoQ) of 0.03 µg/l (Gassner and Jung, 2014).

To account for age-dependency of AMH, participating women in each cohort were divided into four age categories: ≥18–25; ≥25–32; ≥32–40; ≥40 years. These age cut-offs were chosen based on patient numbers, driven by power among the groups, as well as clinical relevance. In each cohort and for each age category, AMH was divided into tertiles with exception of the last age category in which AMH levels varied too little to adequately define tertiles. CCS with an AMH level in the lowest tertile for their age category were defined as having a reduced ovarian function (case), while those with an AMH-value in the highest tertile for their age category were assumed not to have a reduced ovarian function (control). Women over 40 years of age were not considered a ‘case’ based on having an AMH-value in the lowest tertile, but on whether or not they had reported a premature menopause (absence of menses for >12 months before the age of 40) at time of study. No ‘control’ subjects were defined in this age group due to the inability to identify with sufficient certainty those without a reduced ovarian function.

Candidate gene variant selection

SNPs were selected based on a literature search of recently published GWAS that identified loci associated with age at natural menopause (Stolk et al., 2009; He et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2013; van Dorp et al., 2013). Five GWAS hits in DNA damage response pathways, specifically in the inter-strand cross-link repair pathway, were selected based on the lowest P-value in the largest available GWAS meta-analysis, with the hypothesis that polymorphisms in these regions may increase the gonadotoxic effect of alkylating agents. The selected polymorphisms were in UIMC1 (rs365132), FANCI (rs1054875), RAD51 (rs9796), BRSK1 (rs11668344) and MCM8 (rs16991615). Details concerning the genotype data and quality control protocol are provided in the Supplementary materials and methods file, sections ‘Quality protocol’ and ‘Linkage disequilibrium’.

Alkylating agents

For each survivor, the administered cumulative dose of alkylating agents was quantified using the validated cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED) score (Green et al., 2014). To evaluate the effects of no, low-, medium- and high-dose alkylating agent exposure, the CED score was divided into four categories (0; >0–4000 mg/m2; ≥4000–8000 mg/m2; ≥8000 mg/m2) (Green et al., 2014). Details on the administered chemotherapeutics, CED score in categories and a fractional polynomial selection procedure for CED score are further discussed in the Supplementary Tables SI, SII, SIII, SIV and SV.

Statistical analyses

Additive genetic associations, with AMH levels based on imputed allelic dosage, were evaluated by logistic and linear regression analyses based on two models: (i) a main effect model; and (ii) an interaction model. Both models evaluated the association between reduced ovarian function and selected SNPs, adjusted for: ancestry and cohort effects using principle components, CED score (four categories using CED of zero as the reference category) (Green et al., 2014), use of sex hormones (replacement or contraception) at time of study (yes/no), age at time of study (linear regression analysis only) and imputed numbers (0–2) of the alternative allele of the investigated variant (additive effects). The interaction model additionally included an interaction term (SNP*CED category) for genetic variant and CED score categories to evaluate the modifying effect of the variant on the impact of CED score on low AMH levels. Results of linear and logistic regression analyses are presented as regression coefficients (beta) with SE and odds ratios (ORs) with a 95% CI. For linear regression, AMH-levels were log-transformed to adjust for the skewed residuals distribution. Sensitivity analyses performed to assess the robustness of our findings, choices of the model and linkage disequilibrium (Ward and Kellis, 2012) are shown in Supplementary Table SVI. SNPs that showed an association with log-transformed AMH levels or reduced ovarian function in either model, or an interaction effect with CED (P-values < 0.05) were selected for replication of both models. These analyses were conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0.0.1).

Replication and meta-analysis

Findings from the discovery cohort were evaluated in both replication cohorts using identical models, except for sex hormone use at time of study, which was only available in SJLIFE. Data of the discovery and replication cohorts were combined and examined using meta-analytic approaches, in R version 3.5.1, package ‘rmeta’ (R Development Core Team, 2014), the overall P-values for interaction were meta-analysed using Fisher’s method. Pooled estimates based on fixed-effects meta-analysis are presented. In the meta-analysis, P-values <0.01 (0.05/5 gene variants, correcting for multiple testing) were considered statistically significant. Finally, we calculated the cumulative ORs for every genotype per CED category based on the prevalence of a reduced ovarian function for every genotype and every CED category compared to the prevalence of a reduced ovarian function for survivors with a AA genotype treated without alkylating agents, to allow interpretation of the findings.

Results

Discovery cohort

In total, 285 CCS from the DCOG LATER-VEVO cohort participated in the current study (Table I). AMH levels per age category are depicted in Table II. Allele frequencies of the investigated SNPs are depicted in Table III. All SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (significance level <1*10−7). Results from logistic regression analyses showed a negative association between BRSK1 (rs11668344) and reduced ovarian function (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.35–0.90; P-value = 0.016) in the main effect-model. In addition, a non-significantly modifying effect of BRSK1 (rs11668344, minor allele frequency 0.34) on the effect of CED ≥8000 mg/m2 on reduced ovarian function (OR 5.02, 95% CI 0.76–33.08; P-value = 0.09) (Table III) was observed in the interaction model. A significant modifying effect of a polymorphism in FANCI (rs1054875) on the effect of CED in the category >0–4000 mg/m2 (OR 9.93, 95% CI 2.35–41.98; P-value = 0.002) was also observed (Table III). Sensitivity analyses of the main analysis did not change the results (Supplementary Tables SVI and SVII). Linear regression analysis showed a significant main effect of the BRSK1 gene variant, but not of the other variants (Supplementary Tables SVIII and SIX). The two SNPs within the BRSK1 and FANCI genes were assessed for replication in the two replication cohorts.

Table I.

Characteristics of participating CCS in the discovery and two replication cohorts.

| Discovery DCOG LATER-VEVO (n = 285) | Replication PanCareLIFE (n = 465) | Replication St. Jude Lifetime (n = 391) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of study (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 26.1 (18.3–52.4) | 25.7 (18.0–45.0) | 31.3 (19.1–59.5) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 5.8 (0.3–17.8) | 10.4 (0.0–25.0) | 6.9 (0.0–22.7) |

| 18–25 years | 0 (0) | 21 (4.5) | 16 (4.1) |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 19.7 (6.7–41.4) | 17.0 (5.0–39.1) | 23.7 (11.0–46.2) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Leukaemia | 112 (39.3) | 109 (23.4) | 121 (30.9) |

| Lymphoma | 49 (17.2) | 154 (33.1) | 70 (17.9) |

| Renal tumors | 37 (13.0) | 35 (7.5) | 27 (6.9) |

| CNS tumors | 3 (1.1) | 12 (2.6) | 28 (7.2) |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 23 (8.1) | 31 (6.7) | 28 (7.2) |

| Bone tumors | 26 (9.1) | 45 (9.7) | 34 (8.7) |

| Neuroblastoma | 11 (3.9) | 35 (7.4) | 36 (9.2) |

| Other | 24 (8.4) | 44 (9.6) | 47 (12.0) |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| No | 251 (88.1) | 297 (63.9) | 268 (68.5) |

| Yesa | 34 (11.9) | 170 (36.1) | 123 (31.5) |

| Thorax | 22 (7.7) | 88 (18.9) | 71 (18.2) |

| Abdomen (above pelvic crest) | 3 (1.1) | 12 (2.6) | 30 (7.7) |

| Unilateral ovarianb | 0 (0) | 9 (1.9) | 3 (0.8) |

| Other | 20 (7.0) | 61 (13.1) | 51 (13.0) |

| CED score | |||

| 0 | 106 (37.2) | 161 (34.6) | 198 (50.6) |

| >0–4000 mg/m2 | 80 (28.1) | 103 (22.2) | 21 (5.4) |

| ≥4000–8000 mg/m2 | 52 (18.2) | 68 (14.9) | 78 (19.9) |

| ≥8000 mg/m2 | 47 (16.5) | 133 (28.6) | 94 (24.0) |

| Hormone use at serum sampling | |||

| No | 199 (69.9) | 232 (49.9) | 263 (67.3) |

| Yes | 86 (30.1) | 116 (24.9) | 128 (32.7) |

| Oral contraceptive-free day 7 | 70 (24.6) | 3 (0.6) | NA |

| Anytime during oral contraceptive | NA | 94 (20.2) | NA |

| HRT stop 7 | 2 (0.7) | 20 (4.3) | NA |

| Anytime, with intrauterine device | 14 (4.9) | NA | NA |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 117 (25.2) | 0 (0) |

| Unilateral ovarian oophorectomy | |||

| No | 284 (99.6) | 463 (99.6) | 391 (100.0) |

| Yes | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| AMH level | |||

| Median (range) | 2.5 (<0.01–13.1) | 2.1 (<0.01–18.5) | 1.8 (<0.01–11.9) |

| Premature menopause (before age 40) and aged ≥40 years at study, | 2 (0.7) | NA | 4 (1.0) |

Values are represented as the number (%) of women, unless indicated otherwise.

Not mutually exclusive.

Likely in radiotherapy field.

AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone in µg/l; CCS, childhood cancer survivors; CED, cyclophosphamide equivalent dose; CNS, central nervous system; DCOG LATER-VEVO, Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG) LATER VEVO cohort; HRT, hormonal replacement therapy; NA, not available; PanCareLIFE, PanCareLIFE cohort; St. Jude Lifetime, St. Jude Lifetime Cohort.

Table II.

AMH levels in tertiles by age categories.

| VEVO | PanCareLIFE | St. Jude Lifetime | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 18–25 | n = 118 | n = 209 | n = 72 |

| Lowest AMH tertile | 1.08 (0.21–2.14) | 0.66 (0.01–1.79) | 1.48 (0.15–2.20) |

| Middle AMH tertile | 3.07 (2.16–4.08) | 2.51 (1.83–3.39) | 2.79 (2.22–3.56) |

| Highest AMH tertile | 5.37 (4.23–13.14) | 4.98 (3.41–18.50) | 4.91 (3.65–11.90) |

| Age ≥ 25–32 | n = 102 | n = 156 | n = 143 |

| Lowest AMH tertile | 1.32 (0.01–2.14) | 0.72 (0.01–1.49) | 1.16 (0.01–1.84) |

| Middle AMH tertile | 3.09 (2.15–4.59) | 2.33 (1.52–3.26) | 2.57 (1.98–3.57) |

| Highest AMH tertile | 6.08 (4.65–12.76) | 4.32 (3.27–9.08) | 4.87 (3.58–10.48) |

| Age ≥ 32–40 | n = 48 | n = 89 | n = 107 |

| Lowest AMH tertile | 0.36 (0.01–0.80) | 0.05 (0.01–0.50) | 0.51 (0.01–1.04) |

| Middle AMH tertile | 1.33 (0.91–2.16) | 1.19 (0.53–1.90) | 1.69 (1.05–2.10) |

| Highest AMH tertile | 3.65 (2.19–9.44) | 3.42 (1.93–13.50) | 3.27 (2.14–7.70) |

| Age ≥ 40 | n = 17 | n = 11 | n = 69 |

| No tertiles | 0.16 (0.01–1.85) | 0.47 (0.01–8.89) | 0.09 (0.01–8.73) |

Values are represented as the median (minimum–maximum), unless indicated otherwise.

VEVO, DCOG-LATER VEVO cohort.

Table III.

Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms with reduced ovarian function and CED-score in DCOG LATER-VEVO discovery cohort.

| Gene | Variant | Chrom | Ref. | Alt. | MAF | Model | Variant, interaction term | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRSK1 | rs11668344 | 19 | A | G | 0.34 | 1 | rs11668344 | 0.56 (0.35–0.90) | 0.016 |

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.43 (0.65–3.11) | 0.374 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.74 (1.92–11.71) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 5.04 (1.66–15.30) | 0.004 | |||||||

| Hormones | 2.02 (1.00–4.07) | 0.049 | |||||||

| 2 | rs11668344 | 0.57 (0.25–1.31) | 0.186 | ||||||

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.133 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.94 (0.62–6.07) | 0.253 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 5.46 (1.32–22.66) | 0.019 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 1.91 (0.44–8.29) | 0.386 | |||||||

| SNP*CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.218 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 0.66 (0.21–2.13) | 0.489 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 0.85 (0.23–3.18) | 0.807 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 5.02 (0.76–33.08) | 0.094 | |||||||

| Hormones | 2.01 (0.98–4.14) | 0.058 | |||||||

| FANCI | rs1054875 | 15 | A | T | 0.36 | 1 | rs1054875 | 1.01 (0.61–1.67) | 0.975 |

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.37 (0.63–2.95) | 0.425 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.17 (1.73–10.05) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 4.98 (1.66–14.91) | 0.004 | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.79 (0.91–3.54) | 0.094 | |||||||

| 2 | rs1054875 | 0.31 (0.11–0.90) | 0.032 | ||||||

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.009 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 0.32 (0.10–1.06) | 0.063 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 2.19 (0.60–7.95) | 0.235 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 3.71 (0.84–16.38) | 0.084 | |||||||

| SNP*CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.016 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 9.93 (2.35–41.98) | 0.002 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 3.49 (0.78–15.57) | 0.102 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 2.00 (0.38–10.44) | 0.413 | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.83 (0.90–3.73) | 0.095 | |||||||

| MCM8 | rs16991615 | 20 | G | A | 0.08 | 1 | rs16991615 | 0.90 (0.38–2.15) | 0.817 |

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.37 (0.64–2.94) | 0.420 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.16 (1.74–9.97) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 4.96 (1.65–14.87) | 0.004 | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.80 (0.91–3.56) | 0.089 | |||||||

| 2 | rs16991615 | 0.85 (0.21–3.39) | 0.820 | ||||||

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.005 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.36 (0.59–3.14) | 0.473 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.48 (1.73–11.58) | 0.002 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 3.82 (1.22–11.95) | 0.021 | |||||||

| SNP*CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.973 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.07 (0.14–8.06) | 0.950 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 0.61 (0.05–6.74) | 0.683 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | NA | NA | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.89 (0.95–3.75) | 0.069 | |||||||

| UIMC1 | rs365132 | 5 | G | T | 0.5 | 1 | rs365132 | 1.09 (0.70–1.69) | 0.720 |

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.35 (0.63–2.91) | 0.443 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.18 (1.75–10.00) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 5.03 (1.68–15.11) | 0.004 | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.80 (0.91–3.54) | 0.090 | |||||||

| 2 | rs365132 | 0.79 (0.39–1.61) | 0.518 | ||||||

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.017 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 0.44 (0.11–1.82) | 0.257 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.05 (1.01–16.19) | 0.048 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 4.83 (0.78–29.90) | 0.091 | |||||||

| SNP*CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.265 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 2.89 (0.93–8.98) | 0.067 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 1.04 (0.32–3.39) | 0.948 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 1.01 (0.17–5.98) | 0.988 | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.78 (0.89–3.57) | 0.104 | |||||||

| RAD51 | rs9796 | 15 | A | T | 0.42 | 1 | rs9796 | 0.94 (0.62–1.44) | 0.787 |

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.37 (0.64–2.94) | 0.419 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.17 (1.74–9.99) | 0.001 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 4.98 (1.66–14.92) | 0.004 | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.79 (0.91–3.53) | 0.092 | |||||||

| 2 | rs9796 | 0.92 (0.43–1.97) | 0.838 | ||||||

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.167 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.66 (0.52–5.33) | 0.397 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 4.33 (1.18–15.91) | 0.027 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 2.34 (0.48–11.42) | 0.291 | |||||||

| SNP*CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.546 | |||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 0.81 (0.28–2.33) | 0.692 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 0.94 (0.29–3.16) | 0.938 | |||||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 2.82 (0.52–15.37) | 0.230 | |||||||

| Hormones | 1.70 (0.85–3.39) | 0.135 |

Alt, alternative allele; Chrom., chromosome; MAF, minor allele frequency; NA, not available; OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference allele; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Position based on position build 37 on https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/. Alt is reported as 0/1/2 (recalculated for presentation only, based on allelic dosage) for CCS with and without reduced ovarian function (see Methods section for details). Model 1: adjusted for principal components, use of hormone use and CED-categories. Model 2: additional to Model 1 interaction term of variant*CED category.

Replication and meta-analysis

The PanCareLIFE and SJLIFE replication cohorts included 465 and 391 female CCS, respectively (Table I). Consistency of AMH across the three cohorts is depicted in Table II. Table IV shows the combined analysis of both replication cohorts and the final meta-analysis including all three cohorts. Separate findings of the replication cohorts can be found in Supplementary Tables SX and SXI. Full details of the meta-analysis and its heterogeneity are described in Supplementary Tables SXII and SXIII, The overall P-value for interaction between rs11668344 (BRSK1) and CED was 0.018. All three single-cohort analyses suggest a consistent modifying effect for the G allele of rs11668344 (BRSK1) on the effect of CED ≥8000 mg/m2 on reduced ovarian function, although the relatively small-sized discovery cohort did not reach significance for this association. The fixed-effects meta-analysis showed an interaction effect of carrying the G allele of rs11668344 in BRSK1 and an exposure to alkylating agents equivalent to a CED score ≥8000 mg/m2 of 3.81 (95% CI 1.85–7.86, P = 3.0 × 10−4), indicating that the odds of reduced ovarian function increased with an increasing number of G alleles and CED score ≥ 8000 mg/m2.Table V shows the ORs for any genotype per CED category compared to female CCS with the AA genotype and treated without alkylating agents. Female CCS who received alkylating agents equivalent to a CED score ≥8000 mg/m2 had a 2.5-fold higher odds of having an AMH serum level in the lowest tertile with one instead of none G allele of rs11668344 in BRSK1 (genotype AG 5.00 (95% CI 3.27–7.63): AA 2.01 (95% CI 1.31—3.08)) and a 3-fold increased odds with the genotype GG (OR 6.53 95% CI 2.36–18.05).

Table IV.

Association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms with reduced ovarian function and chemotherapy in the meta-analyses.

| Replication (PCL+SJLIFE) meta-analysis |

Discovery + Replication (VEVO + PCL + SJLIFE) meta-analysis |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Variant | Ref>Alt | Model | variant, interaction | OR (95% CI) | Direction | P-value | OR (95% CI) | Direction | P-value |

| BRSK1 | rs11668344 | A>G | 2 | rs11668344 | 0.82 (0.54–1.24) | −+ | 0.349 | 0.76 (0.53–1.11) | −−+ | 0.152 |

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 5.5 × 10−4 | 1 (ref) | 5.6 × 10−4 | ||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 0.58 (0.21–1.58) | −− | 0.284 | 0.98 (0.46–2.09) | +−− | 0.964 | ||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 3.42 (1.52–7.67) | ++ | 2.8 × 10−4 | 3.83 (1.90–7.74) | +++ | 1.8 × 10−4 | ||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 1.77 (0.18–17.60) | +− | 0.627 | 1.82 (0.40–8.34) | ++− | 0.442 | ||||

| SNP*CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.016 | 1 (ref) | 0.018 | ||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 3.27 (1.11–9.66) | +− | 0.032 | 1.37 (0.29–6.51) | −+− | 0.690 | ||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 1.04 (0.44–2.48) | +− | 0.922 | 0.98 (0.48–2.02) | −+− | 0.960 | ||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 3.63 (1.66–7.95) | ++ | 1.3 × 10−3 | 3.81 (1.85–7.86) | +++ | 3.0 × 10−4 | ||||

| FANCI | rs1054875 | A>T | 2 | rs1054875 | 1.01 (0.65–1.56) | +− | 0.977 | 0.85 (0.57–1.28) | −+− | 0.432 |

| CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.002 | 1 (ref) | 2.0 × 10−4 | ||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 0.88 (0.28–2.80) | +− | 0.828 | 0.54 (0.23–1.24) | −+− | 0.148 | ||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 5.29 (2.08–13.50) | ++ | 4.7 × 10−4 | 3.91 (1.83–8.33) | +++ | 4.1 × 10−4 | ||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 3.69 (0.37–36.8) | ++ | 0.266 | 3.70 (0.83–16.6) | +++ | 0.088 | ||||

| SNP*CED: 0 | 1 (ref) | 0.869 | 1 (ref) | 0.146 | ||||||

| ‒ >0–4000 | 1.35 (0.46–3.96) | ++ | 0.583 | 2.76 (1.17–6.53) | +++ | 0.021 | ||||

| ‒ ≥4000–8000 | 0.64 (0.29–1.40) | −− | 0.264 | 0.92 (0.46–1.86) | +−− | 0.823 | ||||

| ‒ ≥8000 | 1.03 (0.53–2.03) | ++ | 0.925 | 1.14 (0.61–2.12) | +++ | 0.691 | ||||

PCL, PanCareLIFE cohort; SJLIFE, St. Jude Lifetime Cohort.

Model 2: adjusted for principal components, hormone use (only for VEVO, SJLIFE) and CED−categories and the interaction term of variant*CED category. + = positive association of the SNP with reduced ovarian function in PCL and SJLIFE respectively. − = negative association of the SNP with reduced ovarian function in VEVO, PCL and SJLIFE, respectively.

Table V.

OR per genotype of rs11668344 (BRSK1) and CED score on reduced ovarian function, based on prevalence in three cohorts.

| genotype AA |

genotype AG |

genotype GG |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CED in mg/m2 | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) |

| 0 | 51 (40.8) | 1 (ref) | 36 (40.0) | 0.97 (0.63–1.48) | 14 (31.8) | 0.68 (0.35–1.30) |

| >0–4000 | 19 (37.3) | 0.86 (0.48–1.53) | 19 (38.8) | 0.92 (0.51–1.64) | 5 (29.4) | 0.60 (0.20–1.82) |

| ≥4000–8000 | 36 (69.2) | 3.26 (1.95–5.46) | 36 (66.7) | 3.48 (2.07–5.87) | 7 (43.8) | 1.13 (0.41–3.14) |

| ≥8000 | 43 (58.1) | 2.01 (1.31–3.08) | 62 (77.5) | 5.00 (3.27–7.63) | 18 (81.8) | 6.53 (2.36–18.05) |

n (%) represents the number of cases with reduced ovarian function (% of total) within each genotype group. OR (95% CI) calculated based on the prevalence of a reduced ovarian function for every genotype and every CED category compared to the prevalence of a reduced ovarian function for survivors with a AA genotype treated without alkylating agents.

Linear regression analysis of BRSK1 showed inconsistent associations with AMH in the two replication cohorts, and no significant association was reached in the meta-analysis (Supplementary Table SXIII: beta −0.09, 95% −0.25–0.08). The modifying effect of >0–4000 CED in FANCI (rs1054875) was non-significant in both replication cohorts, and did not reach significance in the meta-analysis (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.17–6.53, P = 0.02) after correction for multiple testing.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the influence of genetic factors on alkylating chemotherapy-induced reduced ovarian function, using AMH as a biomarker, and incorporating two independent and identically phenotyped replication cohorts and a meta-analysis. We report a strong modifying effect of a common SNP (minor allele frequency 0.34) in the BRSK1 gene on the toxicity of high dose alkylating agents, resulting in a 2.5-fold increased odds of a reduced ovarian function for CCS carrying one G allele compared to CCS without this allele and a 3-fold increased odds for CCS carrying two G alleles.

One previous single-centre study evaluated the association between ovarian function in CCS with SNPs associated with age at menopause in the general population reporting that the T allele of rs1172822 of the BRSK1 gene was inversely associated with serum AMH levels (van Dorp et al., 2013). However, this study did not assess interaction between treatment and AMH levels or include validation using replication cohorts. Recently, a SJLIFE GWAS study identified a haplotype associated with an increased risk of premature menopause, especially in the subgroup of CCS who had received pelvic radiotherapy (Brooke et al., 2018). However, the haplotype is beyond the scope of this study as our population excluded survivors treated with bilateral ovarian radiotherapy due to low inter-individual variation of POI and the haplotype is not associated with DNA damage response genes.

The meta-analysis suggests a strong modifying effect of a G allele of a genetic variant in BRSK1 (rs11668344 A>G) on alkylating agent-related reduced ovarian function. The meta-analysis on reduced ovarian function for the main effect of BRSK1, which is associated with an earlier age at menopause in the general population (Stolk et al., 2009; He et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2013), did not find a significant association as the previous single-centre study reported (van Dorp et al., 2013). Representing continuous variables such as CED-score in categories may lead to increased type I error for the detection of interaction effects (Royston and Altman, 1994). Supplementary analyses using fractional polynomials (Supplementary Tables SIII, SIV and SV) show that using the available data, estimating more flexible models to potentially avoid these spurious findings, offers inconclusive results due to lack of power, while not contradicting the results found using the pre-defined categories.

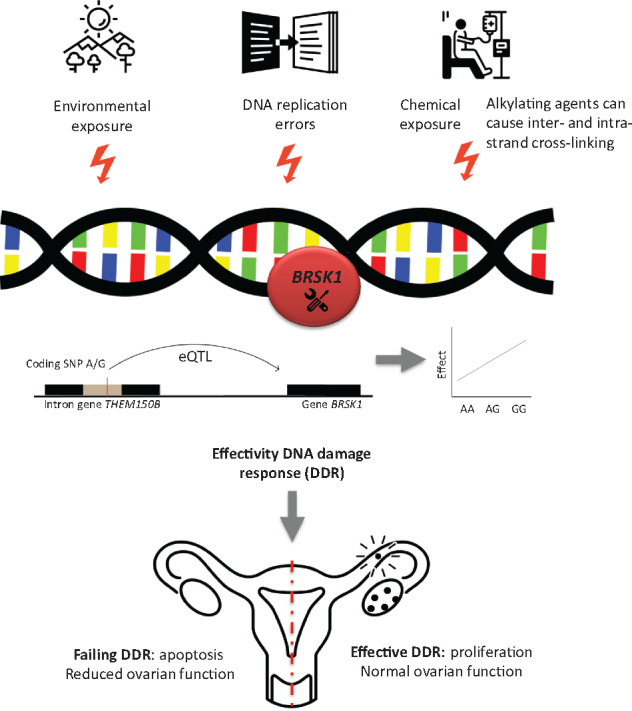

Rs11668344 is an intronic variant in THEM150B and an expression quantitative trait locus that alters BRSK1 RNA gene expression in whole blood (P-value = 2.4 × 10−19) (Westra et al., 2013) and has regulatory histone marks, suggesting a regulatory function. Several mechanisms for the modifying effect of BRSK1 on reduced ovarian function in CCS can be considered. Alkylating agents are known to induce apoptosis of cancer cells by damaging DNA and inhibiting cellular metabolism, DNA replication and DNA transcription (Guainazzi and Schärer, 2010; Kondo et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2012). We hypothesize that due to a less efficient DNA damage response system, cancer patients carrying the G allele of rs11668344 in BRSK1 are at an increased risk of the DNA-damaging impact of alkylating agents in healthy tissues most relevant to our outcome studied here, the ovary (Fig. 1). It is plausible that the efficiency of the DNA damage response system becomes crucial upon treatment with alkylating agents amounting to high CED scores.

Figure 1.

Simplified representation of the hypothesized biological plausibility of the effect of BRSK1 on reduced ovarian function. DNA damage can be the result of environmental exposure, DNA replication errors but also of chemical exposure. Alkylating agents are known to induce apoptosis of cancer cells by damaging DNA and inhibiting cellular metabolism and DNA replication and transcription (Guainazzi and Schärer, 2010; Kondo et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2012). DNA damage response genes (BRSK1 is known to act as a DNA damage checkpoint) have previously been associated with age at natural menopause. Due to a less efficient DNA damage response system, childhood cancer patients carrying the G allele of rs11668344 (BRSK1) may be at an increased risk of the DNA-damaging impact of alkylating agents.

Future research will need to evaluate the relevant expression, which we would expect in granulosa cells or the primordial follicle pool—as opposed to the recruited and selected oocytes that have successfully progressed towards maturation (see also Supplementary file ‘Biological mechanism’).

The identification of this genetic risk factor for alkylating agents-related low AMH levels, if confirmed for other measures of reduced ovarian function, may improve future risk prediction models including more adequate identification of groups with higher or lower risk of chemotherapy-induced ovarian impairment. Upfront fertility preservation programs, including ovarian tissue cryopreservation, would benefit from optimized prediction models as they can be directed to paediatric cancer patients at highest risk for gonadotoxicity for whom the balance of benefits/drawbacks—including ethical considerations—is most beneficial (Warren Andersen, 2018).

A major strength of this study is the inclusion of three independent cohorts which enabled a meta-analysis. As there were some differences between the discovery and the replication cohorts, we performed multiple sensitivity analyses to assess the choices of the model and cohort, which did not change our results. Another strength of this study is the measurement of AMH levels, as a marker for reduced ovarian function, with the same assay at one laboratory, eliminating between-assay differences. Previous studies demonstrated that alkylating agents are strongly associated with risk of reduced ovarian function as measured by decreased AMH levels in female CCS (Anderson et al., 2012; Thomas-Teinturier et al., 2015; van der Kooi et al., 2017; van den Berg et al., 2018). By using AMH levels as a marker of ovarian function, this study included a fairly substantial number of cases likely at increased risk of reduced fertility or a shorter reproductive window. However, while low AMH levels can also identify poor responders in assisted reproductive technology (Iliodromiti et al., 2015; van Tilborg et al., 2017), it needs to be emphasized that AMH remains a surrogate marker of ovarian function. The implications of low AMH on natural fertility and reproductive lifespan are under continuing debate. While in the general population AMH has proven to be a valuable predictor of menopause, apart from age (van Disseldorp et al., 2008; Tehrani et al., 2011; Freeman et al., 2012; Dolleman et al., 2013; Depmann et al., 2016b), current prediction models have not been designed to predict the extremes of menopausal age (Depmann et al., 2016a,b). Validation using data collected long-term and using more definite and direct endpoints such as age at menopause, POI, or fecundity is needed to facilitate translation into clinical practice. In addition, larger cohorts would benefit the power of statistical tests.

In conclusion, this study presents data suggesting that high dose alkylating chemotherapy-induced reduced ovarian function in female CCS is strongly modified by a common DNA variant (rs11668344) of the BRSK1 gene. This is the first time a genetic risk factor has been described to modify the effect of chemotherapy on long-term ovarian function in three independent cohorts. This finding may serve as a starting point for further research working towards individualized counselling regarding treatment-related risks and fertility preservation services in children with cancer as well as young adult survivors.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to ethical reasons and privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author, and after consultation of data and ethics committees of the three separate cohorts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants and staff from all cohorts involved in this study.

The DCOG LATER-VEVO study group includes the following: C.C.M. Beerendonk (Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center), M.H. van den Berg (Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), J.P. Bökkerink (Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center), C. van den Bos (Amsterdam UMC, Universiteit van Amsterdam), D. Bresters (Willem-Alexander Children’s Hospital, Leiden University Medical Center), W. van Dorp (Sophia Children’s Hospital/Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam), M. van Dijk (Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), E. van Dulmen-den Broeder (Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Princess Máxima Center for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht) (Chair), M.P. van Engelen (Wilhelmina’s Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht), M. van der Heiden-van der Loo (Dutch Childhood Oncology Group, Utrecht, Princess Máxima Center for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht), M.M. van den Heuvel-Eibrink (Princess Máxima Center for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht & Sophia Children’s Hospital/Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam), N. Hollema (Dutch Childhood Oncology Group, Utrecht), G.A. Huizinga (University Medical Center Groningen), G.J.L. Kaspers (Princess Máxima Center for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht & Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), L.C. Kremer (Princess Máxima Center for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht &Amsterdam UMC, Universiteit van Amsterdam), C.B. Lambalk (Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), J.S. Laven (Sophia Children’s Hospital/Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam), F.E. van Leeuwen (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam), J.J. Loonen (Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center), M. Louwerens (Willem-Alexander Children’s Hospital, Leiden University Medical Center), A. Overbeek (Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), H.J. van der Pal (Princess Máxima Center for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht), C.M. Ronckers (Princess Máxima Center for Paediatric Oncology, Utrecht), A.H.M. Simons (University Medical Center Groningen), W.J.E. Tissing (University Medical Center Groningen), N. Tonch (Amsterdam UMC, Universiteit van Amsterdam), and A.B. Versluys (Wilhelmina’s Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht).

PanCareLIFE is a collaborative project in the 7th Framework Programme of the European Union. Project partners are: Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany (PD Dr P. Kaatsch, Dr D. Grabow), Boyne Research Institute, Drogheda, Ireland (Dr J. Byrne, Ms H. Campbell), Pintail Ltd., Dublin, Ireland (Mr C. Clissmann, Dr K. O’Brien), Academisch Medisch Centrum bij de Universiteitvan Amsterdam, Netherlands (Dr L.C.M. Kremer), Universität zu Lübeck, Germany (Professor T. Langer), Stichting VU-VUMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands (Dr E. van Dulmen-den Broeder, Dr M.H. van den Berg), Erasmus Universitair Medisch Centrum Rotterdam, Netherlands (Professor M.M. van den Heuvel-Eibrink) (Chair), Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany (Professor A. Borgmann-Staudt, Mr R. Schilling), Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Germany (Professor A am Zehnhoff-Dinnesen), Universität Bern, Switzerland (Professor C.E. Kuehni), IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy (Dr R. Haupt, Dr F. Bagnasco), Fakultni Nemocnice Brno, Czech Republic (Dr T. Kepak), University Hospital, Saint Etienne, France (Dr C. Berger, Dr L. Casagranda), Kraeftens Bekaempelse, Copenhagen, Denmark (Professor J. Falck Winther), Fakultni Nemocnice v Motole, Prague, Czech Republic (Dr J. Kruseova) and Universitaetsklinikum, Bonn, Germany (Dr G. Calaminus, Dr K. Baust).

Data are provided by: Amsterdam UMC bij de Universiteit van Amsterdam, on behalf of the DCOG LATER Study centres, Netherlands (Professor L.C.M. Kremer), Stichting VU-VUMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands (Dr E. van Dulmen-den Broeder, Dr M.H. van den Berg), Erasmus Universitair Medisch Centrum Rotterdam, Netherlands (Professor M.M. van den Heuvel-Eibrink), Princess Máxima Centrum (Professor M.M. van den Heuvel-Eibrink), Netherlands Cancer Institute (Professor F van Leeuwen), Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany (Professor A. Borgmann-Staudt, Mr R. Schilling), Helios Kliniken Berlin-Buch (Dr G. Strauß), Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Germany (Professor A am Zehnhoff-Dinnesen, Professor U. Dirksen), University Hospital Essen (Professor U. Dirksen), Universität Bern, Switzerland (Professor C.E. Kuehni), IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy (Dr R. Haupt, Dr M.-L. Garré), Fakultni Nemocnice Brno, Czech Republic (Dr T. Kepak), University Hospital Saint Etienne, France (Dr C. Berger, Dr L. Casagranda), Kraeftens Bekaempelse, Copenhagen, Denmark (Professor J. Falck Winther), Fakultni Nemocnice v Motole, Prague, Czech Republic (Dr J. Kruseova), Universitetet i Oslo, Norway (Professor S. Fosså), Great Ormond Street Hospital (Dr A. Leiper), Medizinische Universität Graz, Austria (Professor H. Lackner), Medical University of Bialystok, Bialystok, Poland (Dr A. Panasiuk, Dr M. Krawczuk-Rybak), Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf, Germany (Dr M. Kunstreich), Universität Ulm, Germany (Professor H. Cario, Professor O. Zolk), Universität zu Lübeck, Germany (Professor T. Langer), Klinikum Stuttgart, Olgahospital, Stuttgart, Germany (Professor S. Bielack), Uniwersytet Gdánski, Poland (Professor J. Stefanowicz), University College London Hospital, UK (Dr V. Grandage), Sheba Academic Medical Center Hospital, Tel Aviv, Israel (Dr D. Modan-Moses) and Universitaetsklinikum Bonn, Bonn, Germany (Dr G. Calaminus).

Independent ethics advice was provided by professors Norbert W. Paul at the University of Mainz and Lisbeth E. Knudsen from University of Copenhagen.

Authors’ roles

A.-L.L.F.v.d.K., M.v.D., M.M.v.d.H.-E. and E.v.D.-d.B. wrote the article. A.-L.L.F.v.d.K., L.B., J.H.K. and R.J.B. performed the analyses. M.H.v.d.B., F.E.v.L., C.R.R., M.M.H., L.L.R., M.M.H., W.C., S.M.F.P., C.S., J.K. and L.C.K. made suggestions to improve the analyses and the manuscript. L.B., J.S.E.L. and A.G.U. gave their genetic expertise. All other co-authors were involved in the conception and/or data-collection of VEVO, PanCareLIFE or the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. All co-authors reviewed the final article for intellectual content. In all, this document represents a fully collaborative work.

Funding

This work was supported by the PanCareLIFE project that has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 602030. In addition, the DCOG-LATER VEVO study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant no. VU 2006-3622) and by the Children Cancer Free Foundation (Project no. 20) and the St Jude Lifetime cohort study by NCI U01 CA195547.

The ERN PaedCan received funding by the European Union’s Health Programme (2014–2020), grant agreement nr. 768967. The content of this publication represents the views of the author only and it is his/her sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supplementary materials and methods

Quality protocol

For both the DCOG-LATER VEVO and PanCareLIFE cohorts, genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood samples and genotyping was performed using the Global Screening Array by Illumina, as previously described (van Dorp et al., 2013). A quality control (QC) protocol containing multiple filters was applied to clean the genetic data (Anderson et al., 2010). Both a SNP and individual call rate filter of 97.5% were applied to remove poorly genotyped SNPs and individuals from the data. A Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium test (significance level <1*10−7) was employed to remove variants containing potential genotyping errors. Furthermore, samples with excess heterozygosity, gender mismatches and related samples were removed from the data. All samples were from European Ancestry. Imputation was performed using the Michigan Imputation Server using default settings (Das et al., 2016) with the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC r1.1) as reference panel (McCarthy et al., 2016). The same approach has previously been used in large-scale population studies such as the Rotterdam Study (Ikram et al., 2017) and Generation R (Medina-Gomez et al., 2015). Genotyping quality was double checked with the QuantStudio 7 Taqman for BRSK1 (rs1172822).

For the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study, genotyping was performed using Affymetrix HumanSNP6.0 array (Affymetrix Incorporated, Santa Clara, CA, USA). QC of this genotype data was performed using PLINK, version 1.90 and was previously reported (Brooke et al., 2018).

Cyclophosphamide equivalent dose

The impact of alkylating agents on the outcome was assessed using The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED)-Score. The CED is calculated using the following equation: CED (mg/m2) = 1.0 (cumulative cyclophosphamide dose (mg/m2)) + 0.244 (cumulative ifosfamide dose (mg/m2)) + 0.857 (cumulative procarbazine dose (mg/m2)) + 14.286 (cumulative chlorambucil dose (mg/m2)) + 15.0 (cumulative BCNU dose (mg/m2)) + 16.0 (cumulative CCNU dose (mg/m2)) + 40 (cumulative melphalan dose (mg/m2)) + 50 (cumulative Thio-TEPA dose (mg/m2)) + 100 (cumulative nitrogen mustard dose (mg/m2)) + 8.823 (cumulative busulfan dose (mg/m2)).

Full details of the alkylating agents administered in each cohort are presented in Supplementary Table SII, as well as the number of survivors treated with other chemotherapeutic agents.

The impact of alkylating agents and the effect of the interaction between CED-score and genotype on the outcome was analysed using the four CED categories that have been presented in the landmark paper by Green et al. (2014). We chose to include CED in categories in the analyses for several reasons: We hypothesized that the interaction effect of genetic determinants on the impact of alkylating agents is not linear: on the one hand, the modifying effect may specifically be apparent above a certain dose threshold; or on the other hand, the effect of a high alkylating agent dose may be thus detrimental that the impact of any genetic determinants is negligible. In addition, outliers in CED score were present in all included cohorts, which has the potential to affect the association disproportionally if CED score would have been analysed linearly (Supplementary Fig. S1). The area under the curve (AUC) and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the models with addition of BRSK1, addition of CED score only, or the combination is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Fractional polynomial selection for CED score

To investigate the possibility that the categorization of the CED score gave rise to a spurious interaction effect, we included a sensitivity analysis with a closed test procedure for fractional polynomials of the CED score. We selected fractional polynomials of CED based on the main effect using the mfp package (R Development Core Team, 2014) which implements the selection procedure proposed by Royston and Altman (1994). We then used these same selected fractional polynomials in the interaction terms. Below we show the results of these models which use respectively the (complex) model with the highest log likelihood, the model when we set the alpha level of the test procedure to 0.2 (resulting in a log transformation) and the linear model which is selected when setting the alpha level to 0.05. We include an indicator for a non-zero value of CED to allow for differences in the outcomes of those who did not receive any CED (Supplementary Tables SIII, SIV and SV).

In the discovery cohort, this fractional polynomial selection procedure did not provide strong indication which, if any, transformation of the CED score is most suitable, including the transformation used for the interaction effect. The linear model which is selected when setting the alpha level to 0.05, shows a non-significant but positive interaction term (Exp(0.126) = OR 1.134; P-value 0.094; joint test P-value of the interaction coefficients: 0.218), congruent with the modifying effect of A>G in BRSK1 gene on the OR of a reduced ovarian function in the main interaction models of the manuscript.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Table SVI) were performed to assess (i) the robustness of the findings and (ii) to evaluate the impact of alternatives to the model. The following sensitivity analyses were performed for the logistic regression model: (i) no adjustment for use of hormones during serum sampling; (ii) including adjustment for age at diagnosis; (iii) including survivors of leukaemia only; (iv) excluding CCS treated with any radiotherapy; (v) excluding CCS treated with unilateral abdominal radiotherapy and unilateral ovary surgery; (vi) not adding survivors aged 40 and up with a known premature menopause to the reduced ovarian function group, but limiting the analysis to survivors aged 18–40 and basing the analyses on AMH levels only; (vii) adding the second age-adjusted AMH tertiles to the highest tertiles, and thus to the group without reduced ovarian function; (viii) comparing survivors with AMH levels below −2 SD to survivors above −1 SD (SD scores based on control group from the DCOG-LATER VEVO study).

Linkage disequilibrium

Two variants in BRSK1 (rs11668344 and rs1172822) have been genome-wide significantly associated with age at natural menopause and early menopause (Stolk et al., 2009; He et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2013). The two SNPs are in high linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 0.88) (,Ward and Kellis, 2012), indicating a non-random association of these variants. We selected rs11668344 for our analysis as this was the most recently published SNP, and provide the results of rs1172822 as proof of principle (Supplementary Tables SVII, SVIII, SIX, SX, SXI, SXII, and SXIII).

Heterogeneity in the meta-analysis

We present pooled estimates based on the fixed effects model, as a summary yields a more precise estimate of the true effect than any study alone. For random effects the estimate of the between-studies variance may be substantially in error when only three studies are included. In addition, looking at the characteristics of our three independent cohorts, we hypothesized that heterogeneity would not be a large issue. To assess this hypothesis did not cause unjustified inflated results, heterogeneity between the eligible studies was assessed using the estimated heterogeneity variance with corresponding P-values (P-value <0.05 indicating heterogeneity could not be rejected). Low estimates of heterogeneity variance indicated sufficient similarity between studies indicating that pooling using fixed effects was not unreasonable. None of the pooled estimates discussed in the results section of the main manuscript had high estimates of heterogeneity variance (P-values all well above 0.05) (see Supplementary Tables SXII and SXIII).

Biological mechanism

In the Genotype-Tissue Expression project GTEx database (GTEx Consortium, 2013), the expression of BRSK1 seems specifically high in hypothalamic–pituitary tissue and not in ovarian tissue. The ovarian RNA expression data from the GTEx database are, however, less relevant to our study as data were derived from predominantly post-menopausal women (GTEx Consortium, 2013), who likely have a depleted primordial ovarian follicle pool and absence of AMH secreting small growing follicles. Yet, we do consider the option that the brain may be a target tissue relevant to our findings. Demonstrated changes in neurotransmitter vesicle transport caused by the rs11668344 SNP in the brain-specific serine/threonine kinase I gene (BRSK1) (Rodríguez-Asiain et al., 2011) may cause disruption of GnRH secretion in the brain.

In addition, BRSK1 is activated through phosphorylation by the master upstream LKB1 kinase (Bright et al., 2008; Sample et al., 2015), a major metabolic checkpoint which regulates most AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-related activation (Shackelford and Shaw, 2009), that in turn has been linked to DNA damage response (Hurov et al., 2010). A recent study showed that the deletion of LKB1 expressed in mouse oocytes leads to premature activation of the entire primordial follicle pool resulting in premature ovarian failure (Jiang et al., 2016). LKB1 additionally phosphorylates AMP-kinases including the maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK). MELK is expressed in mammalian oocytes and regulates cell polarity through its involvement in the polar body upon cell division (Thélie et al., 2007; Jiang and Zhang, 2013). BRSK1 has been identified as a mitotic cell cycle checkpoint that inhibits progression through cell cycle in response to DNA damage (Lu et al., 2004). However, while BRSK1 regulates the γ-tubulin phosphorylation during centrosome duplication in mice (Carrera and Alvarado-Kristensson, 2009), human oocytes use a spindle stability process independent of γ-tubulin (Feng et al., 2016).

References

- Anderson RA, Brewster DH, Wood R, Nowell S, Fischbacher C, Kelsey TW, Wallace WHB.. The impact of cancer on subsequent chance of pregnancy: a population-based analysis. Hum Reprod 2018;33:1281–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Nelson SM, Wallace WH.. Measuring anti-Mullerian hormone for the assessment of ovarian reserve: when and for whom is it indicated? Maturitas 2012;71:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Clarke GM, Cardon LR, Morris AP, Zondervan KT.. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat Protoc 2010;5:1564–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright NJ, Carling D, Thornton C.. Investigating the regulation of brain-specific kinases 1 and 2 by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2008;283:14946–14954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke RJ, Im C, Wilson CL, Krasin MJ, Liu Q, Li Z, Sapkota Y, Moon W, Morton LM, Wu G. et al. A high-risk haplotype for premature menopause in childhood cancer survivors exposed to gonadotoxic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110:895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne J, Grabow D, Campbell H, O'Brien K, Bielack S, Am Zehnhoff-Dinnesen A, Calaminus G, Kremer L, Langer T, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. et al. PanCareLIFE: The scientific basis for a European project to improve long-term care regarding fertility, ototoxicity and health-related quality of life after cancer occurring among children and adolescents. Eur J Cancer 2018;103:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera AC, Alvarado-Kristensson M.. SADB kinases license centrosome replication. Cell Cycle 2009;8:4005–4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J, Raviv L, Applegarth L, Ford JS, Josephs L, Grill E, Sklar C, Sonoda Y, Baser RE, Barakat RR.. A cross-sectional study of the psychosexual impact of cancer-related infertility in women: third-party reproductive assistance. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier AM, Chong AL, Gingras-Hill G, Ahmed S, Cigsar C, Gupta AA, Greenblatt E, Hodgson DC.. Anti-Mullerian hormone screening to assess ovarian reserve among female survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2014;8:548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow EJ, Stratton KL, Leisenring WM, Oeffinger KC, Sklar CA, Donaldson SS, Ginsberg JP, Kenney LB, Levine JM, Robison LL. et al. Pregnancy after chemotherapy in male and female survivors of childhood cancer treated between 1970 and 1999: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:567–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Forer L, Schonherr S, Sidore C, Locke AE, Kwong A, Vrieze SI, Chew EY, Levy S, McGue M. et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet 2016;48:1284–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day FR, Ruth KS, Thompson DJ, Lunetta KL, Pervjakova N, Chasman DI, Stolk L, Finucane HK, Sulem P, Bulik-Sullivan B. et al. Large-scale genomic analyses link reproductive aging to hypothalamic signaling, breast cancer susceptibility and BRCA1-mediated DNA repair. Nat Genet 2015;47:1294–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day FR, Thompson DJ, Helgason H, Chasman DI, Finucane H, Sulem P, Ks Whalen R, Sarkar S, Albrecht AKE. et al. Genomic analyses identify hundreds of variants associated with age at menarche and support a role for puberty timing in cancer risk. Nat Genet 2017;49:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depmann M, Broer SL, van der Schouw YT, Tehrani FR, Eijkemans MJ, Mol BW, Broekmans FJ.. Can we predict age at natural menopause using ovarian reserve tests or mother's age at menopause? A systematic literature review. Menopause 2016a;23:224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depmann M, Eijkemans MJ, Broer SL, Scheffer GJ, van Rooij IA, Laven JS, Broekmans FJ.. Does anti-Mullerian hormone predict menopause in the general population? Results of a prospective ongoing cohort study. Hum Reprod 2016b;31:1579–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, Griesinger G, Kelsey TW, La Marca A, Lambalk C. et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:370–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolleman M, Faddy MJ, van Disseldorp J, van der Schouw YT, Messow CM, Leader B, Peeters PH, McConnachie A, Nelson SM, Broekmans FJ.. The relationship between anti-Mullerian hormone in women receiving fertility assessments and age at menopause in subfertile women: evidence from large population studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:1946–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy C, Allen S.. Medical and psychosocial aspects of fertility after cancer. Cancer J 2009;15:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R, Sang Q, Kuang Y, Sun X, Yan Z, Zhang S, Shi J, Tian G, Luchniak A, Fukuda Y. et al. Mutations in TUBB8 and human oocyte meiotic arrest. N Engl J Med 2016;374:223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR.. Anti-mullerian hormone as a predictor of time to menopause in late reproductive age women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:1673–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Calvo JA, Samson LD.. Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:104–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassner D, Jung R.. First fully automated immunoassay for anti-Mullerian hormone. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014;52:1143–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, Whitton JA, Srivastava D, Leisenring WM, Neglia JP, Sklar CA, Kaste SC, Hudson MM. et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Sklar CA, Boice JD Jr, Mulvihill JJ, Whitton JA, Stovall M, Yasui Y.. Ovarian failure and reproductive outcomes after childhood cancer treatment: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JCO 2009;27:2374–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GTEx Consortium. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 2013;45:580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guainazzi A, Schärer OD.. Using synthetic DNA interstrand crosslinks to elucidate repair pathways and identify new therapeutic targets for cancer chemotherapy. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010;67:3683–3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Kraft P, Chasman DI, Buring JE, Chen C, Hankinson SE, Pare G, Chanock S, Ridker PM, Hunter DJ.. A large-scale candidate gene association study of age at menarche and age at natural menopause. Hum Genet 2010;128:515–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson MM, Ehrhardt MJ, Bhakta N, Baassiri M, Eissa H, Chemaitilly W, Green DM, Mulrooney DA, Armstrong GT, Brinkman TM. et al. Approach for classification and severity grading of long-term and late-onset health events among childhood cancer survivors in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:666–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurov KE, Cotta-Ramusino C, Elledge SJ.. A genetic screen identifies the Triple T complex required for DNA damage signaling and ATM and ATR stability. Genes Dev 2010;24:1939–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram MA, Brusselle GGO, Murad SD, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, Goedegebure A, Klaver CCW, Nijsten TEC, Peeters RP, Stricker BH. et al. The Rotterdam Study: 2018 update on objectives, design and main results. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:807–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliodromiti S, Anderson RA, Nelson SM.. Technical and performance characteristics of anti-Mullerian hormone and antral follicle count as biomarkers of ovarian response. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21:698–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZZ, Hu MW, Ma XS, Schatten H, Fan HY, Wang ZB, Sun QY.. LKB1 acts as a critical gatekeeper of ovarian primordial follicle pool. Oncotarget 2016;7:5738–5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Zhang D.. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK): a novel regulator in cell cycle control, embryonic development, and cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:21551–21560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N, Takahashi A, Ono K, Ohnishi T.. DNA damage induced by alkylating agents and repair pathways. J Nucleic Acids 2010;2010:543531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langeveld NE, Grootenhuis MA, Voute PA, de Haan RJ, van den Bos C.. Quality of life, self-esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology 2004;13:867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM, Whitton JA, Ginsberg JP, Green DM, Leisenring WM, Stovall M, Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Sklar CA.. Nonsurgical premature menopause and reproductive implications in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 2018;124:1044–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie FS, Laven JS, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, Schipper I, Visser JA, Themmen AP, de Jong FHMM, vdH E.. Assessment of ovarian reserve in adult childhood cancer survivors using anti-Mullerian hormone. Hum Reprod 2009;24:982–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Niida H, Nakanishi M.. Human SAD1 kinase is involved in UV-induced DNA damage checkpoint function. J Biol Chem 2004;279:31164–31170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunsford AJ, Whelan K, McCormick K, McLaren JF.. Antimullerian hormone as a measure of reproductive function in female childhood cancer survivors. Fertil Steril 2014;101:227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, Delaneau O, Wood AR, Teumer A, Kang HM, Fuchsberger C, Danecek P, Sharp K. et al. ; Haplotype Reference Consortium. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet 2016;48:1279–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Gomez C, Felix JF, Estrada K, Peters MJ, Herrera L, Kruithof CJ, Duijts L, Hofman A, van Duijn CM, Uitterlinden AG. et al. Challenges in conducting genome-wide association studies in highly admixed multi-ethnic populations: the Generation R Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SM, Messow MC, McConnachie A, Wallace H, Kelsey T, Fleming R, Anderson RA, Leader B.. External validation of nomogram for the decline in serum anti-Mullerian hormone in women: a population study of 15,834 infertility patients. Reprod Biomed Online 2011;23:204–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek A, van den Berg M, Kremer LCM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Tissing WJE, Loonen JJ, Versluys B, Bresters D, Kaspers GJL, Lambalk CB. et al. A nationwide study on reproductive function, ovarian reserve and risk of premature menopause in female survivors of childhood cancer: design and methodological challenges. BMC Cancer 2012;12: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek A, van den Berg MH, van Leeuwen FE, Kaspers GJL, Lambalk CB, van Dulmen-den Broeder E.. Chemotherapy-related late adverse effects on ovarian function in female survivors of childhood and young adult cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2017;53:10–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JRB, Corre T, Esko T, Chasman DI, Fischer K, Franceschini N, He C, Kutalik Z, Mangino M, Rose LM. et al. A genome-wide association study of early menopause and the combined impact of identified variants. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:1465–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JR, Stolk L, Franceschini N, Lunetta KL, Zhai G, McArdle PF, Smith AV, Aspelund T, Bandinelli S, Boerwinkle E. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies two loci influencing age at menarche. Nat Genet 2009;41:648–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environtment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Asiain A, Ruiz-Babot G, Romero W, Cubí R, Erazo T, Biondi RM, Bayascas JR, Aguilera J, Gómez N, Gil C. et al. Brain Specific Kinase-1 BRSK1/SAD-B associates with lipid rafts: modulation of kinase activity by lipid environment. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1811:1124–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Altman DG.. Regression using fractional polynomials of continuous covariates: parsimonious parametric modelling. J R Stat Soc C (Appl Stat) 1994;43:429–467. [Google Scholar]

- Sample V, Ramamurthy S, Gorshkov K, Ronnett GV, Zhang J.. Polarized activities of AMPK and BRSK in primary hippocampul neurons. Mol Biol Cell 2015;26:1935–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford DB, Shaw RJ.. The LKB1-AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:563–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk L, Zhai G, van Meurs JB, Verbiest MM, Visser JA, Estrada K, Rivadeneira F, Williams FM, Cherkas L, Deloukas P. et al. Loci at chromosomes 13, 19 and 20 influence age at natural menopause. Nat Genet 2009;41:645–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani FR, Shakeri N, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Azizi F.. Predicting age at menopause from serum antimullerian hormone concentration. Menopause 2011;18:766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thélie A, Papillier P, Pennetier S, Perreau C, Traverso JM, Uzbekova S, Mermillod P, Joly C, Humblot P, Dalbiès-Tran R.. Differential regulation of abundance and deadenylation of maternal transcripts during bovine oocyte maturation in vitro and in vivo. BMC Dev Biol 2007;7:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Teinturier C, Allodji RS, Svetlova E, Frey MA, Oberlin O, Millischer AE, Epelboin S, Decanter C, Pacquement H, Tabone MD. et al. Ovarian reserve after treatment with alkylating agents during childhood. Hum Reprod 2015;30:1437–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trama A, Botta L, Foschi R, Ferrari A, Stiller C, Desandes E, Maule MM, Merletti F, Gatta G, Group E-W.. Survival of European adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer in 2000-07: population-based data from EUROCARE-5. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:896–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek RD, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Laven JSE, de Jong FH, Themmen APN, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, van den Bos C, van den Berg H, Pieters R, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SMPF.. Anti-Mullerian hormone is a sensitive serum marker for gonadal function in women treated for Hodgkin's lymphoma during childhood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:3869–3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg H, Repping S, van der Veen F.. Parental desire and acceptability of spermatogonial stem cell cryopreservation in boys with cancer. Hum Reprod 2007;22:594–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg MH, Overbeek A, Lambalk CB, Kaspers GJL, Bresters D, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Kremer LC, Loonen JJ, van der Pal HJ, Ronckers CM. et al. ; DCOG LATER-VEVO study group. Long-term effects of childhood cancer treatment on hormonal and ultrasound markers of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod 2018;33:1474–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van der Kooi A-LLF, Wallace WHB.. Fertility preservation in women. N Engl J Med 2018;378:399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooi ALF, Kelsey TW, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Laven JSE, Wallace WHB, Anderson RA.. Perinatal complications in female survivors of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2019a;111:126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooi ALF, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van den Berg SAA, van Dorp W, Pluijm SMF, Laven JSE.. Changes in anti-Mullerian hormone and inhibin B in children treated for cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2019b;8:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooi AL, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van Noortwijk A, Neggers SJ, Pluijm SM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, van Dorp W, Laven JS.. Longitudinal follow-up in female childhood cancer survivors: no signs of accelerated ovarian function loss. Hum Reprod 2017;32:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooi A-LLF, Clemens E, Broer L, Zolk O, Byrne J, Campbell H, van den Berg M, Berger C, Calaminus G, Dirksen U. et al. ; on behalf of the PanCareLIFE Consortium. Genetic variation in gonadal impairment in female survivors of childhood cancer: a PanCareLIFE study protocol. BMC Cancer 2018;18:930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Disseldorp J, Faddy MJ, Themmen AP, de Jong FH, Peeters PH, van der Schouw YT, Broekmans FJ.. Relationship of serum antimullerian hormone concentration to age at menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2129–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dorp W, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Stolk L, Pieters R, Uitterlinden AG, Visser JA, Laven JS.. Genetic variation may modify ovarian reserve in female childhood cancer survivors. Hum Reprod 2013;28:1069–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tilborg TC, Torrance HL, Oudshoorn SC, Eijkemans MJC, Koks CAM, Verhoeve HR, Nap AW, Scheffer GJ, Manger AP, Schoot BC. et al. ; on behalf of the OPTIMIST study group Individualized versus standard FSH dosing in women starting IVF/ICSI: an RCT. Part 1: the predicted poor responder. Hum Reprod 2017;32:2496–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LD, Kellis M.. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:D930–D934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren Andersen S. Identifying biomarkers for risk of premature menopause among childhood cancer survivors may lead to targeted interventions and wellness strategies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110:801–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HJ, Peters MJ, Esko T, Yaghootkar H, Schurmann C, Kettunen J, Christiansen MW, Fairfax BP, Schramm K, Powell JE. et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat Genet 2013;45:1238–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, Embry L, Aguilar C, Meeske KA, Li Y, Butler M, Cole S.. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer 2013;119:201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Clarke GM, Cardon LR, Morris AP, Zondervan KT.. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat Protoc 2010;5:1564–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke RJ, Im C, Wilson CL, Krasin MJ, Liu Q, Li Z, Sapkota Y, Moon W, Morton LM, Wu G. et al. A high-risk haplotype for premature menopause in childhood cancer survivors exposed to gonadotoxic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110:895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Forer L, Schonherr S, Sidore C, Locke AE, Kwong A, Vrieze SI, Chew EY, Levy S, McGue M. et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet 2016;48:1284–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, Whitton JA, Srivastava D, Leisenring WM, Neglia JP, Sklar CA, Kaste SC, Hudson MM. et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HaploReg v4.1. Broad Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He C, Kraft P, Chasman DI, Buring JE, Chen C, Hankinson SE, Pare G, Chanock S, Ridker PM, Hunter DJ.. A large-scale candidate gene association study of age at menarche and age at natural menopause. Hum Genet 2010;128:515–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram MA, Brusselle GGO, Murad SD, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, Goedegebure A, Klaver CCW, Nijsten TEC, Peeters RP, Stricker BH. et al. The Rotterdam Study: 2018 update on objectives, design and main results. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:807–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, Delaneau O, Wood AR, Teumer A, Kang HM, Fuchsberger C, Danecek P, Sharp K. et al. ; Haplotype Reference Consortium. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet 2016;48:1279–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Gomez C, Felix JF, Estrada K, Peters MJ, Herrera L, Kruithof CJ, Duijts L, Hofman A, van Duijn CM, Uitterlinden AG. et al. Challenges in conducting genome-wide association studies in highly admixed multi-ethnic populations: the Generation R Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]