Abstract

We recently reported that restoring the CYP27A1-27hydroxycholesterol axis had anti-tumor properties. Thus we sought to determine the mechanism by which 27HC exerts its anti-PC effects. As cholesterol is a major component of membrane micro-domains known as lipid rafts, which localize receptors and facilitate cellular signaling, we hypothesized 27HC would impair lipid rafts, using the IL6-JAK-STAT3 axis as a model given its prominent role in PC. As revealed by single molecule imaging of DU145 PC cells, 27HC treatment significantly reduced detected cholesterol density on the plasma membranes. Further, 27HC treatment of constitutively active STAT3 DU145 PC cells reduced STAT3 activation and slowed tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. 27HC also blocked IL-6 mediated STAT3 phosphorylation in non-constitutively active STAT3 cells. Mechanistically, 27HC reduced STAT3 homodimerization, nuclear translocation and decreased STAT3 DNA occupancy at target gene promoters. Combined treatment with 27HC and STAT3 targeting molecules had additive and synergistic effects on proliferation and migration, respectively. Hallmark IL6-JAK-STAT gene signatures positively correlated with CYP27A1 gene expression in a large set of human metastatic castrate-resistant PCs and in an aggressive PC subtype. This suggest STAT3 activation may be a resistance mechanism for aggressive PCs that retain CYP27A1 expression. In summary, our study establishes a key mechanism by which 27HC inhibits PC is by disrupting lipid rafts as evidence by blocking of STAT3 activation.

Implications:

Collectively, these data show that modulation of intracellular cholesterol by 27HC can inhibit IL6-JAK-STAT signaling and may synergize with STAT3 targeted compounds.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is the most common non-cutaneous cancer in American men (1). Recent reports have emphasized the role of diet and lifestyle as important modifiable predictors of PC risk (2–4). Of all dietary factors, cholesterol has received much attention for its role in PC (5–13). Early observations in the 1940s showed that cholesterol levels are elevated in PC adenocarcinomas compared to benign prostate tissue (14,15). Importantly, epidemiologic and pre-clinical studies have found a link between higher serum cholesterol and greater PC incidence and/or progression (8,10). Furthermore, many studies found cholesterol-lowering drugs (primarily HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, a.k.a. statins) are inversely linked with PC incidence and/or progression, including reduced risk of advanced disease (16). Collectively, these data suggest the potential of altering cholesterol homeostasis to treat and/or prevent PC.

Prostate cells maintain intracellular cholesterol homeostasis via intricate feedback mechanisms (17–19). During PC tumorigenesis, the mechanisms that govern cholesterol homeostasis are often dysregulated, leading to increased intracellular cholesterol accumulation (5), thereby altering important signaling pathways and promoting cell survival and growth (20) (21) (22).

Our group recently found that cholesterol homeostasis-related genes are correlated with PC outcomes, and published a report linking p450 sterol hydroxylase CYP27A1 loss and PC (5). In normal non-neoplastic cells, when high levels of cholesterol accumulate intracellularly, CYP27A1 hydroxylates cholesterol to create 27-hydxroycholesterol (27HC), which can bind to and activate the Liver-X-Receptor transcription factors (LXR-alpha and LXR-beta) (23). Activated LXRs modulate cholesterol metabolism by increasing reverse cholesterol transport thereby reducing intracellular cholesterol levels (24). In PC, we found that CYP27A1 and hence 27HC are frequently lost (5). Further, we found that restoration of CYP27A1 reduced intracellular cholesterol and decreased PC tumor growth in vitro and in vivo (5). Similarly, 27HC treatment also reduced intracellular cholesterol and reduced tumor growth in vitro. Overall, our findings identified the CYP27A1/27HC axis as a cholesterol biosensor in PC cells and demonstrated that restoration of this axis inhibits PC growth (5). However, the exact mechanism by which 27HC inhibits PC growth remains unclear.

Cholesterol is a crucial building block in the cell, with a majority localized to the lipid bilayer within specific membrane-associated micro-domains called lipid rafts (25–28). Many studies showed that intact membrane lipid rafts are important to facilitate signal transduction in cancer cells. Zhuang et al. (20) showed cholesterol depletion via statins depleted lipid raft levels, promoted AKT pathway signaling, and increased apoptosis. Sehgal et. al demonstrated that pathways initiated by cytokine stimulation, such as the interleukin-6 (IL6)-JAK-STAT pathway, are activated via raft-dependent signaling (20,25,28). Another study by Kim et. al showed that IL-6 mediated lipid raft signaling was disrupted after membrane-cholesterol depletion in PC cells (25). In sum, these reports suggest that intact lipid rafts are essential for sustaining pro-oncogenic signaling in cancer cells, including signaling via the IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway.

The IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway is comprised of extracellular IL-6 ligand activating IL-6 receptors, which phosphorylate JAK, which in turns phosphorylates STAT3. Phosphorylated STAT3 dimerizes and translocates into the nucleus to induce expression of genes with various pro-tumorigenic properties (29). In addition, IL-6-JAK-STAT3 is a known to be an important signaling pathway in PC (29,30). Multiple studies have shown that inhibiting this pathway can control PC growth in preclinical models (31–33) and analysis of human metastatic castrate resistant PC (mCRPC) rapid autopsy biopsies show elevated levels of activated p-STAT3 and IL-6 receptor (IL6R) in bone metastases compared to lymph node and visceral metastases (34), validating the importance and therapeutic potential of this pathway in PC.

Given that 27HC exhibits anti-PC properties, we sought to determine the mechanism by which this occurs. We hypothesized that 27HC impairs lipid raft mediated signaling via cholesterol depletion, which then alters pro-oncogenic signaling pathways in PC. We tested this hypothesis using IL6-JAK-STAT3 as a model signaling pathway given it requires functional lipid rafts and is important in PC (30,34,35). This is the first study to provide a mechanistic basis for the anti-tumor activity of 27HC in PC.

Methods and Materials

CYP27A1 expression correlation with disease stage and pathway IL6-JAK-STAT3

To assess CYP27A1 expression in human PCs and correlation with IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway activity, we used an easy-to-use web-based software named the Prostate Cancer Transcriptome Atlas (PCTA) (www.thepcta.org). This software currently provides two large sets of PC transcriptome profiles including the PCTA consisting of 2,115 PC samples described in You et al. (36) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) prostate adenocarcinoma cohort consisting of 551 PC samples. Pathway activation score was computed by using Z-score method (37). Correlation between CYP27A1 and IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway activation was computed by Spearman’s rank correlation method.

Cell lines and culture conditions

All cell lines were obtained and authenticated by ATCC. DU145 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) +10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). PC3, 22RV1 and LNCaP cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) +10%FBS. 27HC was purchased from Enzo (Farmingdale, NY) and the LXR agonists GW3965 and TO1317 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 27HC and LXR agonists were resuspended using DMSO in a 10mM stock. STAT3 inhibitors SH-4–54 and C188–9 were also purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX) and resuspended at 50 mM in DMSO.

Western Blots

Cells were collected using a cell scraper in 1X Protein lysis buffer (1X RIPA with 1X protease cocktail inhibitor 1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 1X phosphatase cocktail inhibitor 2, 1X phosphatase cocktail inhibitor 2). Cells were then rotated at 4°C and centrifuged at 15000xg. The supernatant was collected, and protein was quantified in this fraction using DC Biorad protein assay (Biorad, Hercules, CA) using BSA standard. For each blot, 30–60μg of protein was loaded and run on 10% SDS page gels. Gels were transferred onto 0.45uM nitrocellulose paper and were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% BSA in TBST. p-STAT3Y705, total STAT3, p-JAK2Y1007/1008 and total JAK2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), were all used at 1:1000. After incubation, blots were washed three times with 1X TBST and incubated with rabbit or mouse secondary at 1:10000. Following the incubation, blots were washed three times with 1X TBST and appropriate ECL kits were used to develop the blot. For nuclear/cytoplasmic extracts from DU145 cells, the NE-PER kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were treated with DMSO or 27HC (10uM) in PD150 plates for 48h. Following treatment, cells were collected in 1X PBS using a cell scraper. Of the total cell pellet, 1/10th was aliquoted and immediately frozen at −80°C and served as the whole cell lysate. The remaining cell pellet was then processed for cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. For western blot quantification, ImageJ 1.52a software was utilized to quantify band densitometry for p-STAT3, total STAT3 and Actin or GAPDH loading controls for normalization. For normalized intensity calculations, first p-STAT3 and STAT3 values were divided by their respective loading control values. The resulting normalized values were then divided (p-STAT3/STAT) to generate a normalized intensity value. When shown as percentage, treatment group ratios were divided by control group ratio (100%) and multiplied by 100.

Co-immunoprecipitation

STAT3 monomer and dimers were assessed by co-immunoprecipitation western blot as previously described (38). Briefly, LNCaP cells were treated with vehicle control or IL-6 recombinant protein for 1h and lysed with 0.5% NP-40 lysis buffer on an end-over-end rotor at 4°C. Protein lysates were incubated with mouse anti-STAT3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers MA) on an end-over-end rotor at 4°C for 2h and followed by incubation with protein A beads for 1h. Pulldowns were washed with NP-40 lysis buffer and heated for 5 min in Laemmli loading buffer for elution. p-STAT3Y705 monomers and dimers were then probed for with a rabbit polyclonal p-STAT3Y705 antibody.

Fluorescent cholesterol probe design, purification, and direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM) imaging.

Perfringolysin O Domain 4 (PFO-D4 C459A) (39,40) was used as a cholesterol probe for direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM) imaging. The single engineered N-terminal cysteine was used for attachment of an Alexa Fluor 647-C2-Maleimide label. The expression plasmid was custom made by Genscript and contained a cleavable N-terminal His6-Smt3 tag (41) for affinity purification. The expression plasmid was transfected into BL12 cells (NEB) and induced with IPTG. After incubation, the cells were pelleted and resuspended in buffer A (50mM Phosphate pH 7.9, 300mM NaCl) with protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich S8830). Cells were then lysed by French press and cell debris pelleted by ultra-centrifugation at 45,000 RPM for 45min at 4°C. Protein was purified with HisPur Cobalt Resin (Thermo Pierce, Waltham, MA) and dialyzed into PBS. The His6-SMT3 tag was cleaved with SUMO protease Ulp1 and both the tag and the protease were removed by passing through additional cobalt-affinity resin. Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647) maleimide was used for labeling of protein according to manufacturer’s protocol. Excess label was removed by a Bio-Gel P-4 gel filtration column (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Sample purity and monomeric state were verified by PAGE gels and size exclusion chromatography. We obtained degree of labeling equal to one, indicating single Cys residue was labeled with AF647. We refer to the resulting construct as PFO-D4-AF647.

Sample preparation.

DU145 cells were cultured in Phenol Red-free DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 units/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-alanyl-L-glutamine. At least 24h before imaging, cells were seeded on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips (2 μg/cm2 of fibronectin in PBS pH 7.4). Where indicated, 10μM 27HC in DMSO or DMSO alone (0.1% total volume) were added to culture media for 2–48h. Cholesterol depletion controls were performed by incubating cells in 10mM Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), 10mM HEPES, 1 mg/ml BSA, and serum free DMEM media for 40min at 37°C as before (42). Cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 300 nM PFO-D4-AF647 for 30min at room temperature in buffer B (PBS supplemented with 5% BSA, 0.01% Tween-20, and 1mM CaCl2). Excess PFO-D4-AF647 was removed by washing three times with buffer B before being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The fixative was quenched with 25mM glycine before being removed. Finally, the cells were washed 3 times with PBS and TetraSpec beads (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) were added to serve as fiducial markers for drift-correction.

dSTORM imaging and analysis.

Samples were imaged on a Nikon 3D N-STORM microscope using a 100x objective in total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) mode with 647 nm excitation. 20,000 frames were acquired at 100Hz using NIS-Elements 4.3 software (Nikon, Minato, Japan). These raw images were processed by NIS-Elements to extract the x-y locations for each fluorophore appearance and the results were exported for analysis with custom MATLAB code. Pair-correlation analysis (42) was used to quantify clustering. This method calculates the autocorrelation curves of regions of interest (ROIs) to provide cluster size, increased local density (cluster density divided by average density), and the number of detected molecules per cluster. Pair-correlation analysis considers multiple localizations from the same fluorescent reporter. We used DU145 cells sparsely labeled with PFO-D4-AF647 (random monomers) to calculate the average number of localizations for each reporter. This parameter was found to be 2 and was incorporated into pair-correlation analysis and density calculations.

Lipid raft FACS analysis

For determination of lipid raft integrity by flow cytometry analyses, cells were treated as indicated for 48h. Subsequently, media was removed, and cells were washed with RPMI base media (without serum) then 0.5μM of di-4-ANEPPDHQ (in 2ml of RPMI base media) was added to each well for 30min. Cells were then washed with PBS, trypsinized, and resuspended in 500ul of PBS+1%BSA. Samples were analyzed on a BD LSR II Flow Cytometer. Generalized polarization (GP) values were calculated using the following equation GP= (LO+LD)/(LO-LD), using FlowJo. GP values are a measure of membrane order, with values ranging from −1 (denoting that all the emission is collected in the disordered, long-wavelength channel) to +1 (denoting that all the fluorescence is collected in the ordered channel) (43).

Proliferation assays

DU145 or PC3 cells were plated in a 96 well black walled, clear bottom plate and after 36h, cells were treated as specified for 72h using DMSO as a vehicle. CyQUANT proliferation assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) was used according to manufactures instructions and read on the SpectraMax M3 plate reader ex:485 and em:510nm. Drug combination studies were conducted on an IncuCyte® S3 live cell imaging system (Essen Bioscience, Ann Arbor, Michigan) on 96 whole well scan mode. Plates were imaged every 24h and quantified with bundled image analysis software and normalized cell confluence to treatment day 0.

Kinetic cell migration and Matrigel invasion

Scratch wound migration and matrigel invasion assays were conducted on an IncuCyte® S3 live cell imaging system (Essen Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI). DU145 cells (4.5 × 105) were plated on imagelock 96 well plates and treated for 24h with indicated drug. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and a 96-pin wound making tool was used to make a uniform scratch in all 96 wells simultaneously (IncuCyte® 96-well WoundMaker Tool, Cat# 4563) and cell debris was wash off with PBS. For cell migration assays complete DMEM media was added with indicated treatments. For matrigel invasion assays, scratch wound was overlaid with 3μg/mL of matrigel and incubated for 1h at 37C. Once solidified matrigel was overlaid with 100uL of DMEM media with indicated treatments. Images were acquired every 2h. Quantification was conducted using IncuCyte® Scratch Wound software module.

RNA and quantitative real time PCR

DU145 cells were treated in 6 wells with DMSO or 27HC for 48h. Cells were rinsed with 1X PBS and RNA was collected from cells using Qiagen RNeasy kit with DNAse digestion. Following isolation, RNA was quantified using the Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and reverse transcribed using Biorad iScript cDNA synthesis kit using 1μg of RNA. For RT-qPCR, 10ng of cDNA was used per reaction using Superscript SYBR green (Biorad, Hercules, CA) and assays were performed on ABI Viia7 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Primer sequences available in supplementary materials.

ChIP-qPCR.

ChIP-qPCR experiments were performed with the ChIP-IT High Sensitivity kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 80% confluent DU145 cells treated for 48h with vehicle (50% ethanol and 50% DMSO) or 27HC (10μM) were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10min. Chromatin was sonicated to 100–500 bp in a Bioruptor UCD-200 (Diagenode, Denville, NJ) and 30 ug of chromatin per reaction was incubated overnight with the pertinent amount of antibody recommended by manufacturer p-STAT3Y705 (D3A7) XP antibody (cat#9145), STAT3 (79D7) Rabbit mAb (cat#4904) Cell Signaling or IgG control. Following RNase A and Proteinase K treatment, ChIP DNA was purified with the column system provided with the kit and quantitative PCR conducted. A negative primer set that amplifies a 78 base pair fragment from a gene desert on human chromosome 12 (Human Negative Control Primer Set 1, Active Motif) was used as a control. Primer sequences available in supplementary materials.

In vivo xenograft study

Mouse experiments were conducted as approved by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center IACUC board protocol number IACUC006565. Male severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice were purchased from Taconic Biosciences (Oxnard, CA) and acclimated for 48h according to IACUC policy. DU145 cells (1.0 × 106) cells were injected in a 1:1 solution of base DMEM medium and Matrigel in the lower right flank of mice and tumors were allowed to grow to approximately 200 mm3 prior to randomization to cyclodextrin vehicle control or 27HC (40mg/kg) treatment group injected subcutaneously daily as previously described (44).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 7.04 was used for statistical analysis of in vitro studies. For time-course live cell spheroid assays, multiple t-tests were conducted and multiple comparisons correction adjusted p-value calculated by Holm-Sidak method with alpha=0.05. For time-course live cell proliferation assays and migration/invasion assays, 2-way repeated measures ANOVA multiple comparison analysis was conducted with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test for adjusted p-value both with alpha=0.05. To evaluate the combined effects of 27HC and STAT3 inhibitors, a modified coefficient of drug interaction (CDI) equation was used (45). Briefly, the CDI is calculated as follows: CDI = AB/(A × B). AB is the effect of the combination groups compared to control group; A or B is the percent inhibition of the single agent group compared to control group. CDI <1 indicates that the drugs are synergistic, CDI=1 indicates drugs are additive and >1 antagonistic. A CDI <0.7 indicates that the drug combination is significantly synergistic (45). To compare tumor growth kinetics in vivo, a generalized estimating equation with exchangeable correlation was used to test whether tumor volume growth varied over time between the two treatment arms. Time was treated as a categorical variable to not assume linear growth. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

CYP27A1 expression in PC disease states and PCS subtypes

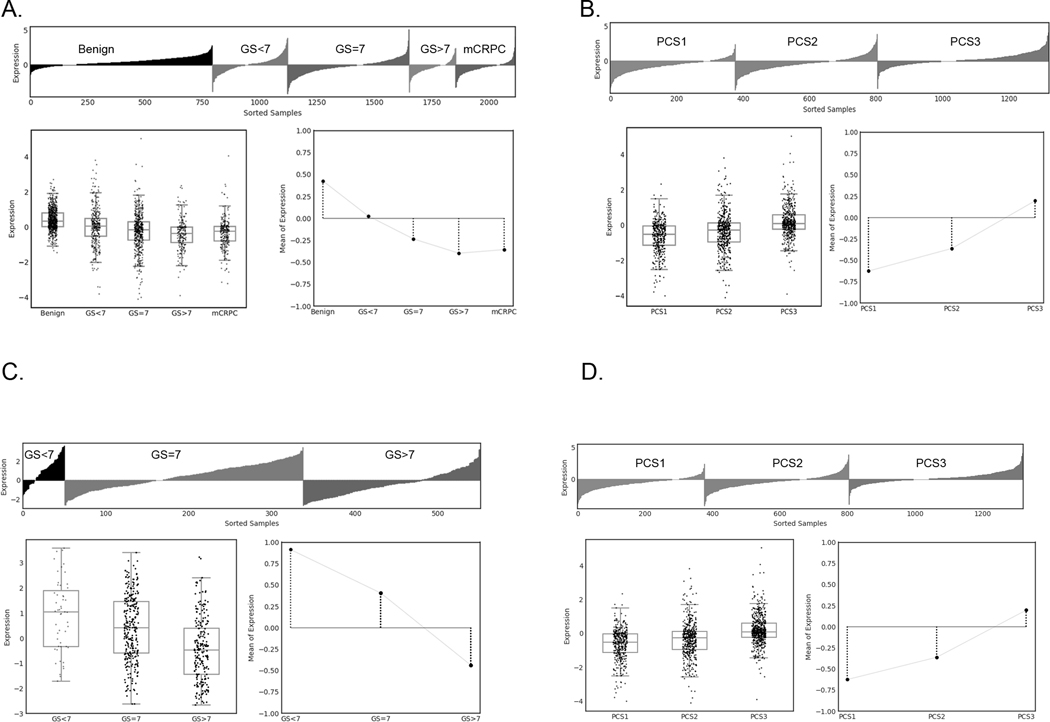

We previously observed that CYP27A1 mRNA was downregulated in PC vs normal benign prostate in multiple independent gene expression data sets (5). To reassess our previous findings, we queried a virtual pooled cohort of 2,115 patient samples consisting of 1,321 PCs and 794 benign prostate tissues and found that CYP27A1 mRNA expression is progressively down-regulated from benign to metastatic castrate resistant PC (Fig. 1A). One-way ANOVA test revealed significant differences across different grades and disease states (F-value = 84.774, P-value < 0.001). Binary comparisons of Primary versus Benign (log2 fold change = −0.612, P-value < 0.001) and mCRPC versus Primary (log2 fold change = −0.171, P-value < 0.001) represent statistical significance by two-tailed Rank-Sum test. In addition, applying a previously described novel PC subtyping algorithm (36) we found that CYP27A1 expression is lowest in Prostate Cancer Subtype 1 (PCS1), the most lethal PC subtype (Fig. 1B) (F-value = 88.854, P-value < 0.001). Similar findings were observed from One-way ANOVA test of TCGA samples showing significantly lower expression levels of CYP27A1 in GS>7 vs other Gleason subsets (GS=7 and GS<7) (Fig. 1C) (F-value = 36.768, P-value < 0.001) and PCS1 vs other subtypes (PSC2 and PCS3) (F-value = 97.764, P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. CYP27A1 gene expression is progressively downregulated during progression and in lethal PCS1 subtype.

Lollipop plot, box plot and line plot display expression profiles of individual samples, distribution of gene expression, and average expression and trend lines of the gene expression in each disease category, respectively. Plots show CYP27A1 gene expression in 5 disease categories from (A) PCTA samples (F-value = 84.774, P-value < 0.001) and (C) TCGA samples (F-value = 36.768, P-value < 0.001). Plots show CYP27A1 expression in 3 PCS categories for (B) PCTA samples (F-value = 88.854, P-value < 0.001) and (D) TCGA samples (F-value = 97.764, P-value < 0.001). GS=Gleason Score, mCRPC=metastatic castration resistant PC, and PCS=Prostate Cancer Subtype.

Visualization of 27HC-induced cholesterol depletion

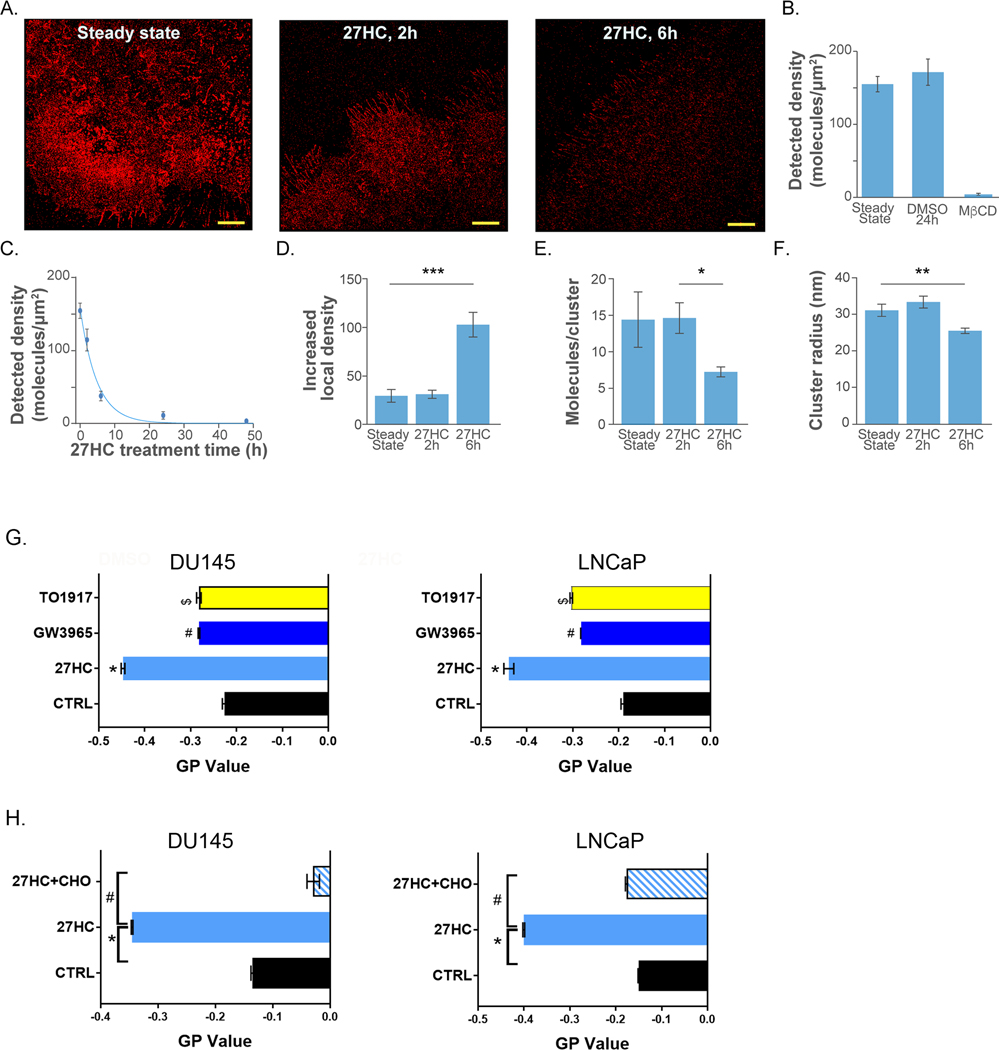

To visualize the effects of 27HC on membrane cholesterol, we optimized labeling of cholesterol with PFO-D4-AF647, which binds cholesterol at residues T490 and L491 (Fig. S1A). We found that the fluorescent signal saturated at approximately 300nM PFO-D4-AF647 and we therefore used this concentration for all experiments (Fig. S1B). DU145 cell image and detected density of cholesterol in the steady state are shown in Fig. 2A left and Fig. 2B, respectively. To test the effect of cholesterol depletion, we treated DU145 cells with 10mM Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) as previously described (42). MβCD treated cells that were labeled with PFO-D4-AF647 had negligible fluorescent signal (Fig. 2B), consistent with the known effects of MβCD to significantly strip cells of cholesterol. To determine the effect of 27HC treatment on membrane cholesterol, we imaged DU145 cells treated for 2, 6, 12, and 48h. The density of detected cholesterol molecules decreased significantly by 2h (p-value<0.001) and was negligible after 24 and 48h (Fig. 2A and Fig. 2C). The negligible fluorescent signal after 24–48h treatment suggests that cholesterol content was below the mole percent threshold for this probe (46). As a control, 24-hour treatment with DMSO had no significant effect on detected cholesterol density (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2: Cholesterol density and distribution is altered in DU145 cell membranes upon treatment with 27HC.

(A) dSTORM images of DU145 cells after varying 27HC incubation times. Scale bars are 5μM. (B) Detected cholesterol densities in steady state, after 24h incubation with 0.1% DMSO, and after 40min of cholesterol depletion with 10mM MβCD. (C) Densities of detected molecules vs 27HC incubation times. The blue line shows best exponential fit to the data (time constant 4.8h). (D-F) Clustering metrics averaged over all ROIs as calculated by pair-correlation analysis for varying 27HC incubation times: steady state, 27HC 2h treatment, and 27HC 6h treatment. (D) Increased local density. (E) Detracted molecules per cluster. (F) Cluster radius. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. For each condition, minimum of 12 cells and 47 ROI’s were analyzed. (G) GP values of flow cytometry analyzed di-4-ANEPPDHQ for lipid raft organization in DU145 and LNCaP cells in cells treated as denoted (10μM) for 48h and (H) 27HC treated cells ± cholesterol (CHO) (10ug/ml) supplementation (n=3, *p=0.001, #p<0.01, $p<0.05).

To characterize the cholesterol enriched domains (clusters) in the image, pair-correlation analysis (42) was used. Pair-correlation analysis was applied to data obtained in steady state, after 2h of 27HC treatment, and after 6h of 27HC treatment. The resulting auto-correlation curves and clustering metric histograms are shown in Fig. S2. Cluster properties showed very small change between steady state and 2h. After 6h, smaller cluster radius, fewer molecules per cluster, and a larger increased local density were detected, on average (Fig. 2D–F). This indicates that after 6h treatment with 27HC, cholesterol enriched domains are largely reorganized. Overall, our dSTORM data suggest that 27HC treatment 1) reduces cholesterol density in time dependent manner; and 2) leads to reorganization of cholesterol enriched domains after 6h treatment. Though 27HC lead to even further declines in membrane cholesterol at 24 hrs (Fig 2 C) suggesting 27HC has lasting effects on membrane cholesterol, its effects on cluster properties at these later time points were tested.

27HC causes lipid raft disorganization and depletes membrane cholesterol

Given 27HC reduced plasma membrane cholesterol, which is crucial for lipid raft formation, we assessed lipid raft microdomains using the fluorescent based probe di-4-ANEPPDHQ as previously described (47). Flow cytometry analysis of di-4-ANEPPDHQ showed that 27HC, but not the LXR agonists GW3965 or TO1317 reduced general polarization (GP) values marking disorganization and loss of rigidity of lipid raft microdomains in DU145 and LNCaP cells (Fig. 2G). Moreover, supplementation of exogenous cholesterol rescued lipid raft microdomain GP values (Fig. 2H), confirming the direct importance of cholesterol depletion for these effects.

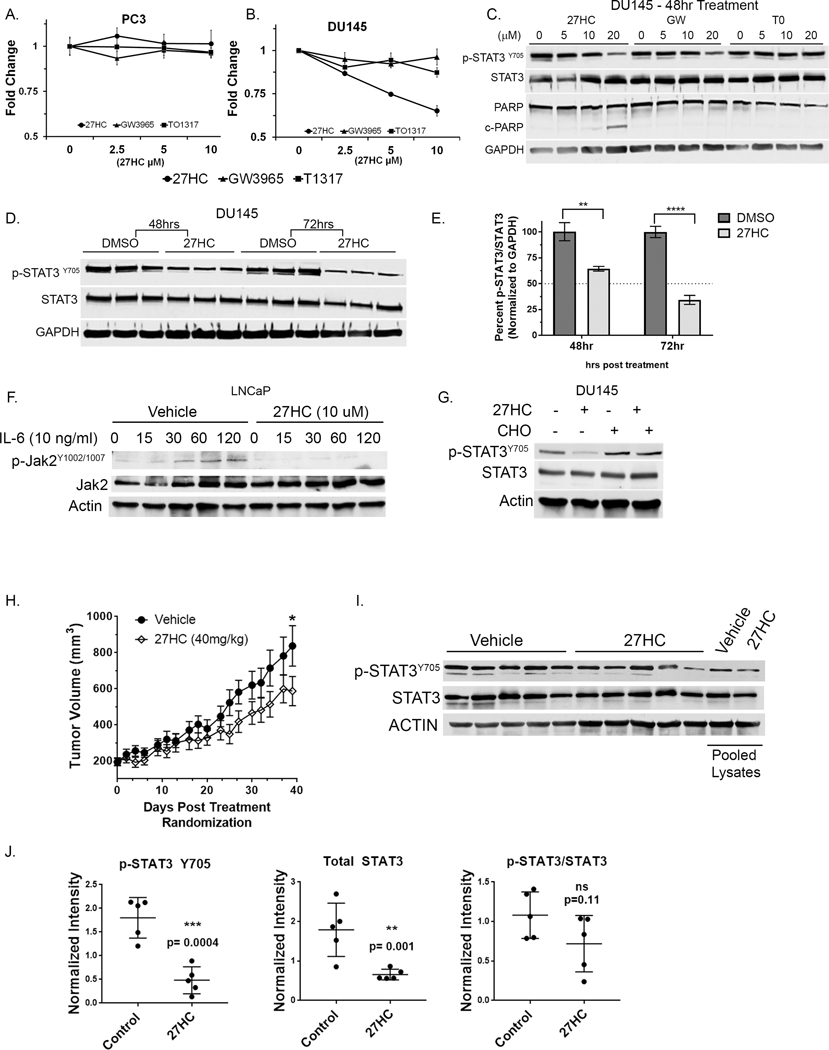

27HC reduces p-STAT3Y705 levels in DU145 cells

To examine the importance of 27HC’s anti-proliferative effects via IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, we utilized two cell lines with altered JAK-STAT3 signaling: DU145 with constitutively active STAT3 (p-STAT3Y705) and PC3 that are STAT3 null (48) (49). As shown in Figs. 3A–B, DU145 and PC3 cell proliferation was not affected by LXR agonists GW3965 or TO1317 after 72h. However, 27HC at 5μM and 10μM elicited a growth inhibitory response at 72h in DU145 cells, but not the STAT3 null PC3 cells. Interestingly, we found that 27HC and GW3965, but not TO1317 altered p-STAT3Y705 levels at 48h (Fig 3C). However, only 27HC treatment induced cell death as denoted by cleaved PARP1. Relative to DMSO control at each time point, western blot analysis of p-STAT3Y705 showed downregulation of STAT3 activity to ~66% at 48h and further to ~33% at 72h post 27HC (10μM) treatment relative DMSO controls (Fig 3D–E). These data further demonstrate the importance of disrupting lipid membranes as evidenced by inhibition of the IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway in mediating 27HC’s anti-proliferative effects.

Figure 3. 27HC effects on PC cell growth and STAT3 signaling in vitro and in vivo.

(A) PC3 and (B) DU145 cell growth response to LXR agonists 27HC, GW3965 and TO1317 at indicated doses after 72h of treatment by MTT assay. (C) STAT3 activation and cell death assessed by p-STAT3 and PARP1 cleavage in DU145 cell lysates treated with various doses of LXR agonists (0–20 μM) for 48hrs as indicated. (D) Activation of STAT3 assessed in DU145 cells at 48 and 72hr post treatment with 27HC (10 μM) treated in triplicate. (E) Percent active STAT3 (p-STAT3/STAT3) normalized to GAPDH by densitometry. **p=0.0049; ****p<0.0001. (F) Upstream JAK2 activation was assessed in LNCaP cells pretreated with 27HC for 48h and then stimulated with rIL-6 (10ng/ml) and cell lysates collected at indicated times (min). (G) DU145 cells were supplemented with cholesterol (CHO) alone or in 27HC treated cells for 72h and cell lysates probed as indicated showing that CHO rescues 27HC mediated STAT3 inactivation. (H) DU145 xenograft tumor growth kinetics in vivo injected subQ with vehicle (cyclodextrin) or 27HC (40 mg/kg) daily. (I) Endpoint tumor lysates (n=5/group) immunoblotted as indicated (individually and pooled) and (J) blot pixel densitometry of bands normalized to actin bands and plotted.

27HC inhibits recombinant IL-6 mediated JAK2 and STAT3 phosphorylation

To determine the effects of 27HC on STAT3 upstream JAK2 activation, LNCaP cells, which have low basal levels of p-STAT3Y705, were pretreated with vehicle control or 27HC (10μM) for 48h and then treated with recombinant IL6 (rIL-6) (10 μg/ml) and cells collected at denoted time points. Western blot analysis for p-JAK2Y1002/1007 (Fig. 3E) showed increased p-JAK2 within 30–60min following IL-6 treatment in vehicle pretreated LNCaP cells with essentially no p-JAK2 increase in 27HC (10μM) pretreated cells.

To test if downregulation of p-STAT3Y705 is mediated by 27HC induced cholesterol loss, cell culture media was supplemented with exogenous cholesterol. As previously demonstrated, 27HC treatment downregulated p-STAT3 levels, while co-treatment of 27HC and cholesterol rescued 27HC induced p-STAT3Y705 down regulation (Fig 3F) suggesting the effects of 27HC on p-STAT are mediated via cholesterol depletion. Overall, these data demonstrate that 27HC decreases JAK2 phosphorylation, which in turn reduces p-STAT3Y705 activation, and these effects may be rescued by exogenous cholesterol supplementation.

27HC reduces DU145 xenograft tumor growth

To test if 27HC could slow STAT3 driven tumors in vivo, we grafted 1×106 DU145 cells to male SCID mice. When tumors were ~200mm3 mice were randomized to control or 27HC treatment groups. Mice were injected daily (s.c.) with vehicle (cyclodextrin) or 27HC in cyclodextrin (40mg/kg) for 37 days as previously described (44). There was a statistically significant difference in tumor growth between the two treatment arms (time X treatment p-interaction <0.001), with slower tumor growth in mice treated with 27HC (Fig. 3G). Western blot analysis of tumor lysates showed reduced p-STAT3Y705 and total STAT3 in tumors from 27HC treatment groups compared to vehicle control (Fig. 3H and 3I), but no significant difference the ratio of p-STAT3/STAT3 (Fig. 3J). Our in vivo experiment demonstrated that 27HC treatment of the aggressive DU145 xenografts reduces STAT3 levels, STAT3 activation and slowed tumor growth in vivo. STAT3 has an autoregulatory role, thus long-term treatment in vivo with 27HC (i.e. 37 days) vs 72 hrs in vitro may account for reduced total STAT3 levels in vivo, but not in vitro (50) (51).

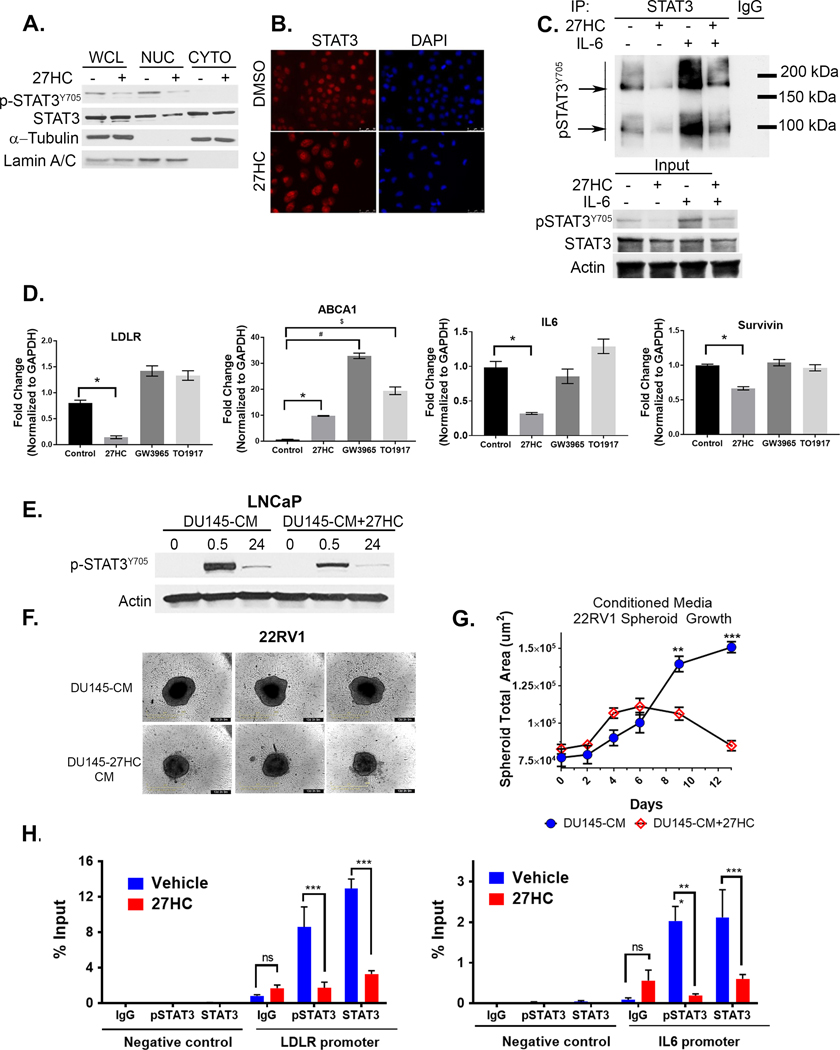

27HC inhibits STAT3 dimer formation, nuclear localization, and target gene expression

STAT3Y705 phosphorylation is necessary for STAT3 dimer formation, nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity. Given that 27HC inhibited STAT3 phosphorylation, we conducted cell nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation experiments, which showed 27HC reduced total and p-STAT3Y705 levels in nuclear fractions of DU145 cells (Fig. 4A). This was confirmed by immunofluorescence showing increased levels of total STAT3 in the cytoplasm of DU145 cells treated with 27HC vs DMSO for 72h vs. nuclear localization in DMSO treated cells (Fig. 4B). p-STAT3Y705 dimer formation, both basal and IL-6 induced, were also inhibited by 27HC treatment in LNCaP cells (Fig. 4C). Well-known STAT3 target genes, IL-6 and Survivin, were significantly down regulated in DU145 cells upon 27HC treatment, but not with treatment using the LXR agonists GW3965 or TO1317 (Fig. 4D). Consistent with previous results, the LXR target gene ABCA1 was significantly upregulated by the LXR agonists and 27HC (Fig. 4D), demonstrating that the LXR agonists were bioactive although they did not elicit a reduction in STAT3 gene targets. Moreover, Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR), was also down-regulated in DU145 cells was only observed in response to 27HC (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. 27HC inhibits STAT3 nuclear localization, dimerization and transcriptional activity.

(A) DU145 whole cell (WCL), nuclear (NUC) and cytoplasmic (CYTO) cell lysate fractions probed as indicated with a-tubulin as cytoplasmic and lamin A/C as nuclear loading controls. (B) Immunofluorescence imaging of total STAT3 (red) in DU145 cells in DMSO or 27HC (10μM) treated cells at 72h. (C) Immunoprecipitation of total STAT3 and immunoblot for p-STAT3 in control LNCaP cells, 27HC pretreated (72h, 10μM), rIL-6 (30min, 10μg/ml) or both. Arrows denote STAT3 monomers and dimers. Input 10% of immunoprecipitation input protein lysates. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of denoted genes in DU145 cells treated as indicated (10 μM) for 48 h (data show mean + S.D. from triplicates.). *=p<0.05; $ and # =p<0.001. (E) Immunoblots of lysates from LNCaP cells treated for 0.5h or 24h with conditioned media from DU145 vehicle control or 27HC treated cells (DU145-CM and DU145-CM+27HC, respectively) in a 1:1 ratio with fresh 10% RPMI-FBS. (F) Individual Day 13 22RV1 spheroid brightfield images at endpoint treated as above. (G) Spheres were imaged periodically using Incucyte® S3 and spheroid size quantified with spheroid module software. (Multiplicity adjusted t-test p values Day 9: p= 0.01; Day 13: p=0.0001; n=5/group). (H) ChIP-qPCR for p-STAT3 and total STAT3 in DU145 cells treated for 48h as denoted (Data show mean + S.D. from triplicates.). p-STAT3 ChIP-qPCR normalized by a factor of 1.5 to account for reduction of p-STAT3 upon 27HC treatment at 48hr. RT-qPCR and ChIP results are representative of two independent experiments.

To confirm the functional effects of IL-6 downregulation and loss of IL-6 autocrine effects, we collected 24h conditioned media (CM) from DU145 control cells (DU145-CM), which produce high levels of IL-6 (52), or cells pretreated with 27HC (DU145–27HC-CM). After 48h of 27HC pretreatment, media was removed, cells washed with PBS and fresh media without 27HC was added and collected after 24h of conditioning. LNCaP cells, which exhibit significantly lower levels of endogenous p-STAT3 (48), were then treated with 1:1 ratio of fresh RPMI media and conditioned media from the DU145 cells for 0.5 or 24h. Immunoblots of LNCaP protein lysates show DU145-CM induced p-STATY705, however this was significantly blunted in LNCaP cells treated with DU145–27HC-CM (Fig. 4E). In addition, time lapse imaging 22RV1 spheroids over 13 days (Fig. 4F) cultured in 1:1 RPMI to DU145–27HC-CM grew significantly slower starting at day 6 compared to DU145-CM 22RV1 spheroids (Fig. 4G) and became smaller after day 9 suggesting cell death. LNCaP were not used given their inability to form uniform spheroids in our hands. Collectively, these data are consistent with 27HC inhibiting IL-6 production by DU145 cells and consequently loss of IL-6 auto- and paracrine effects.

27HC inhibits STAT3 DNA binding activity

Given 27HC reduces STAT3 nuclear localization and downregulates known STAT3 target genes, we assessed STAT3 DNA occupancy by a STAT3-ChIP-qPCR assay with pulldowns for p-STAT3Y705 and total STAT3 at the IL-6 promoter. In addition, our analysis of publicly available STAT3 ENCODE ChIP-Seq data from breast cell lines shows a strong signal at the LDLR promoter, thus we also probed for STAT3 binding at the LDLR promoter. As shown in figure 4H, 27HC significantly reduced total STAT3 and p-STAT3Y705 binding at IL-6 and LDLR promoters compared to control cells. To our knowledge physical binding of STAT3 at the LDLR promoter has not been previously shown. These data show that reduce levels of total STAT3 and p-STAT3Y705 are bound to transcriptional target gene sequences, however we cannot speculate as to effects of 27HC on STAT3 transcriptional complexes or chromatin structure.

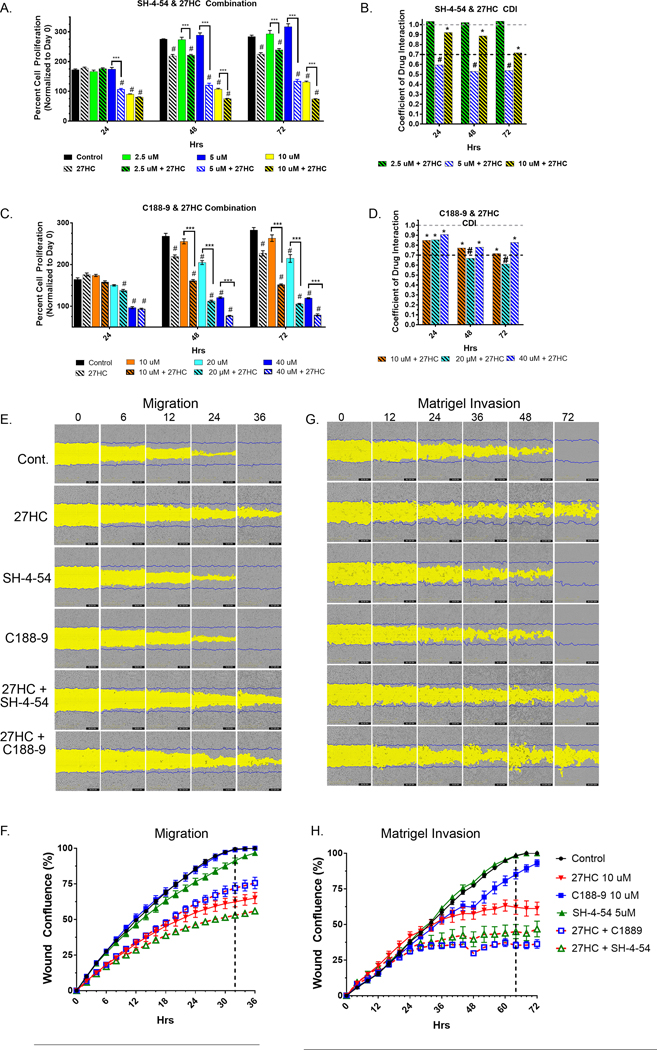

Synergistic anti-proliferative effects of 27HC-STAT3 inhibitor combinations

While 27HC lowers p-STAT3Y705 levels, a moderate level of active STAT3 remains (Fig. 3D). Thus, we tested if 27HC treatment may synergize with STAT3 inhibitors to more fully inhibit STAT3 signaling and thereby reduce proliferation. In this regard, we utilized two STAT3 inhibitors that target the phospho-Y-binding pocket of the STAT3 SH2 domain SH-4–54 (53) and C188–9 (a.k.a TTI-101, ClinicalTrials.Gov Identifier NCT03195699) and further disrupt JAK-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation (54). Preliminary dose response studies were conducted with SH-4–54 and C188–9 individually in DU145 and PC3 to determine combination doses (Supplemental Fig. S3) when combined with 27HC 10μM. Single treatment of DU145 cells with SH-4–54 at 2.5 and 5μM alone had no significant effects vs control, while significant differences in proliferation were detected at 10μM at each time point (p<0.0001) (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the combination of SH-4–54 at 5μM and 27HC had significant synergistic effects (Fig. 5B) 24h post treatment (CDI= 0.60) and onward (Table 1) (45). Synergism (CDI <1 but >0.7) was observed between 27HC and SH-4–54 10μM dose in all time points. Multiple t-test adjusted p values and CDI values for SH-4–54 and 27HC are summarized in Table 1. For C188–9, at the 72h time point all standalone C188–9 dose treatments (10, 20, and 40μM) had significant anti-proliferative effects vs control (Fig. 5C and Table 2). Synergism was observed between all combinations of C188–9 and 27HC beginning at 24h and 20μM C188–9 + 27HC combination became significantly synergistic at 48 and 72h post treatment (Fig. 5D). Complete multiple comparison t-test p values between groups are listed in Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2.

Figure 5. Combined effects of 27HC (10μM) and STAT3 inhibitors SH-4–54 and C-1889 on proliferation, cell migration and matrigel invasion.

(A) 27HC and SH-4–54 combination DU145 cell proliferation studies and (B) CDI value bar graph for drug interactions. (C) 27HC and C-1889 combination DU145 cell proliferation studies and (D) CDI value bar graph for drug interactions. DU145 cells were treated as indicated and imaged every 24h on Incucyte S3 system. Cell proliferation plotted as a percent normalized to Day 0 at time of treatment (n=5/group), #Indicates significant difference compared to DMSO control at denoted time point and bracketed *** indicates statistically significant difference between single agent at indicated dose and 27HC (10μM) combination. (C-D) Above gray dashed line signifies antagonistic effects, *below gray dashed line indicates synergism and #below black dashed line indicates significantly synergistic interaction. Representative images of DU145 (E) scratch wound migration and (F) plotted wound closure kinetics. (G) Scratch wound Matrigel invasion and (H) plotted Matrigel invasion wound closure kinetics. Plotted time course of % wound confluence, vertical dashed lines indicate time point in which DMSO control group reached 100% wound closure.

Table 1.

SH-4–54 and 27HC Combination Summary Table

| Adjusted P Value | CDI Value | Combination Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24hr Time Point | ||||

| Control vs. 27HC | ns | 0.9955 | ||

| Control vs. 2.5 uM | ns | 0.9857 | ||

| Control vs. 5 uM | ns | >0.9999 | ||

| Control vs. 10 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| 2.5 uM + 27HC vs. 2.5 uM | ns | 0.8285 | 1.03 | Antagonistic |

| 5 uM + 27HC vs. 5 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 0.60 | Significantly Synergistic |

| 10 uM + 27HC vs. 10 uM | ns | 0.8934 | 0.92 | Synergism |

| 48hr Time Point | ||||

| Control vs. 27HC | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| Control vs. 2.5 uM | ns | >0.9999 | ||

| Control vs. 5 uM | ns | 0.5826 | ||

| Control vs. 10 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| 2.5 uM + 27HC vs. 2.5 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 1.02 | Antagonistic |

| 5 uM + 27HC vs. 5 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 0.53 | Significantly Synergistic |

| 10 uM + 27HC vs. 10 uM | *** | 0.001 | 0.89 | Synergism |

| 72hr Time Point | ||||

| Control vs. 27HC | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| Control vs. 2.5 uM | ns | 0.946 | ||

| Control vs. 5 uM | *** | 0.0006 | ||

| Control vs. 10 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| 2.5 uM + 27HC vs. 2.5 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 1.04 | Antagonistic |

| 5 uM + 27HC vs. 5 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 0.54 | Significantly Synergistic |

| 10 uM + 27HC vs. 10 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 0.72 | Synergism |

Table 2.

C188–9 and 27HC Combination Summary Table

| Adjusted P Value | CDI Value | Combination Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24hr Time Point | ||||

| Control vs. 27HC | ns | 0.5282 | ||

| Control vs. 10 uM | ns | 0.7551 | ||

| Control vs. 20 uM | ns | 0.2687 | ||

| Control vs. 40 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| 10 uM vs. 10 uM +27HC | ns | 0.167 | 0.85 | Synergism |

| 10 uM vs. 20 μM +27HC | **** | <0.0001 | 0.86 | Significantly Synergistic |

| 10 uM vs. 10 uM +27HC | ns | 0.167 | 0.91 | Synergism |

| 48hr Time Point | ||||

| Control vs. 27HC | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| Control vs. 10 uM | ns | 0.4243 | ||

| Control vs. 20 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| Control vs. 40 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| 10 uM vs. 10 uM +27HC | **** | <0.0001 | 0.77 | Synergism |

| 20 uM vs. 20 uM +27HC | **** | <0.0001 | 0.67 | Significantly Synergistic |

| 40 uM + 27HC vs. 40 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 0.78 | Synergism |

| 72hr Time Point | ||||

| Control vs. 27HC | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| Control vs. 10 uM | * | 0.0339 | ||

| Control vs. 20 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| Control vs. 40 uM | **** | <0.0001 | ||

| 10 uM vs. 10 uM +27HC | **** | <0.0001 | 0.72 | Synergism |

| 20 uM vs. 20 uM +27HC | **** | <0.0001 | 0.61 | Significantly Synergistic |

| 40 uM + 27HC vs. 40 uM | **** | <0.0001 | 0.83 | Synergism |

Effects of 27HC-STAT3 inhibitor combination on cell migration and Matrigel invasion.

Lipids rafts have been shown to be essential for lamellipodia formation and cancer cell migration (55). Likewise, STAT3 overexpression in DU145 and addback to PC3 induced the formation of lamellipodia and increasing tumor metastasis, supporting a role for STAT3 driven migratory phenotype in PC (31). Standard Boyden chamber invasion assays show 27HC significantly slowed matrigel invasion of DU145 cells (Fig. S4). Thus, we tested if 27HC alone or in combination with STAT3 inhibitors inhibits DU145 cell migration (Fig. 5E). At the 32h time point (Fig. 5F, vertical dashed line), which is when the DMSO control group reached 100% wound closure, statistically significant differences in cell migration rates were observed for 27HC (p<0.0001), SH-4–54 + 27HC combination (p<0.0001) and C188–9 + 27HC (p<0.0001) treated groups vs. control (Fig. 5F). No significant effects on cell migration were detected SH-454 or C188–9 treatments vs DMSO control at any time point. In addition, synergism was detected among 27HC + SH-4–54 combination (CDI= 0.93), while antagonistic effects were observed among 27HC + C188–9 (CDI= 1.19).

To test the effects on DU145 Matrigel invasion, scratch wounds were immediately overlaid with Matrigel and wound closure though Matrigel were monitored in real time (Fig. 5G). At the 64h time point, which is when the DMSO control group reached 100% wound closure (Fig. 5H, vertical dashed line), significant effects on matrigel invasion were observed for 27HC (p<0.0001), C188–9 (p<0.01), but not SH-4–54. Significant effects were observed for both combination groups (p<0.0001) vs control. In addition, there was synergism between 27HC + SH-4–54 (CDI= 0.74) and significantly synergistic effects between 27HC + C188–9 (CDI= 0.67) on DU145 Matrigel invasion. Overall, our functional assays demonstrate that 27HC, alone or in combination with STAT3 inhibitors, reduce migration and invasion of DU145 cells.

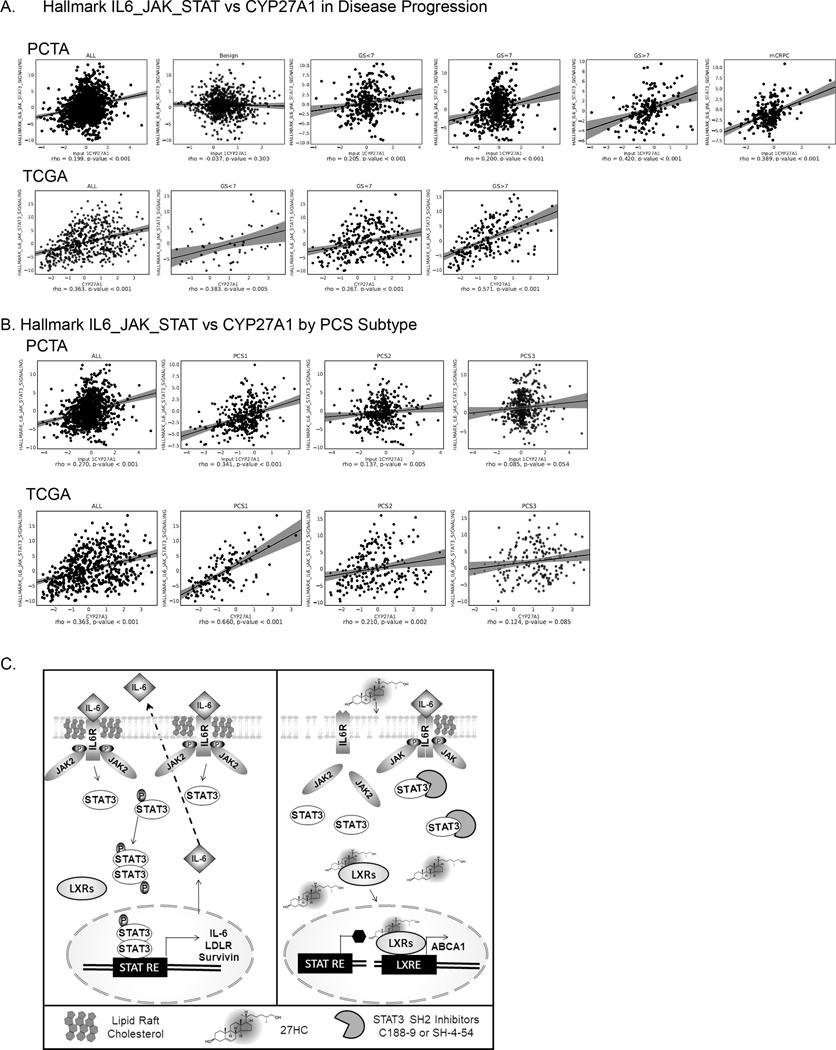

IL6-JAK-STAT3 correlates with retained CYP27A1 in advanced and aggressive PCs.

We assessed the correlation between Hallmark IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway (GSEA M5897) (56) and CYP27A1 expression in PC patients. We used the PCTA web software, which enables easy calculation of a pathway activation score based on the given pathway gene set using the Z-score method (37). We found that the Hallmark IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway in PCTA and TCGA cohorts exhibits significant positive correlation with CYP27A1 expression across all PC disease states with increasingly higher correlation with disease progression. In this regard, in the PCTA data set, no correlation was observed in benign tissues between IL6-JAK-STAT3 and CYP27A1, however Spearman rho values increased with disease progression in GS<7 (rho= 0.205, p<.001), GS= 7 (rho=0.20, p<0.001), GS >7 (rho=0.42, p<0.0001 and mCRPC (rho= 0.389, p value <0.001) (Fig. 6A). Likewise, in the TCGA dataset, IL6-JAK-STAT3 and CYP27A1 correlation rho values increased from GS<7 (rho=0.383, p=0.005), GS=7 (rho=0.267, p<0.0001) and GS>7 (rho=0.571, p<0.001). Importantly, Hallmark IL6-JAK-STAT3 and CYP27A1 positive correlation pattern was observed in AR high (rho= 0.27, p-=0.0001) and AR low tumors (rho= 0.24, p=0.0001) (Fig. S5). Amongst the 3 PC subtype categories (36), the highest correlation rho values were observed in the lethal PCS1 subtype category in both PCTA (rho= 0.341, p<0.001) and TCGA (rho=0.660, p<0.001) data sets (Fig. 6B). These clinical data suggest that, although counterintuitive to the mechanistic data, CYP27A1 expression is positively associated with IL6-JAK-STAT3 signatures in PC tumors and have distinct correlations based on PC subtype and aggressiveness independent of AR status.

Figure 6. Activation of IL6-JAK-STAT pathway is highly correlated with CYP27A1 expression in high grade, mCRPC and lethal PC subtype.

(A-B) Scatter plots and regression lines depicts correlations between IL6-JAK-STAT3 hallmark pathway activation and CYP27A1 gene expression in PC samples from the PCTA virtual cohort and the TCGA cohort. Individual dots on the plot represent individual PC samples from the cohorts. The correlation of all the samples and samples in different disease categories by Gleason score were displayed in both PCTA and TCGA cohorts (A). Correlation pattern in the PCS categories were seen in both PCTA and TCGA cohorts (B). (C) Working model of 27HC action on IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling. Under normal condition increased levels intracellular cholesterol due deregulation of cholesterol homeostasis facilitates lipid raft IL-6-JAK-STAT3 signaling for cell autocrine effects and induction of IL-6 autocrine effects, LDLR, and survival genes (i.e. Survivin). Addition of exogenous 27HC binds and activates LXRs inducing transcriptional program that reduces intracellular and lipid raft cholesterol thus impairing IL-6-JAK-STAT3 signaling and reducing STAT3 target gene expression including IL-6 and LDLR. Addition of STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors may inhibit remaining STAT3 activation by blocking binding to JAK2 SH2 domains. STAT RE= STAT3 Response Element; LXRE: LXR Response Element

DISCUSSION

While we have previously shown that 27HC exerts anti-cancer effects in PC, the mechanistic basis for these observations has not been previously described. In this study we show that 27HC treatment leads to a rapid and profound depletion of plasma membrane cholesterol levels and disruption of lipid raft size and architecture. This, in turn, impairs oncogenic signaling through the well-described IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling axis both in vitro and in vivo, and delayed in vivo tumor growth in a constitutively active STAT3 model of PC growth. Intriguingly, 27HC appeared to sensitize cells to STAT3 inhibitors, a finding that requires further study as a novel treatment paradigm. Our data suggest that 27HC-mediated lipid raft perturbation is a key mechanism in part explaining the anti-PC activity of 27HC as evidenced by altered signaling of the IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway. Importantly, we believe that 27HC, by blocking lipid raft signaling would block multiple key pathways mediated by lipid rafts. Herein we used STAT3 as our model, but our data do not exclude the high likelihood that other lipid raft mediated pathways are also disrupted.

Following 27HC treatment, we saw a rapid reduction in detected plasma membrane cholesterol that was significant within 2h of treatment and continued to decline up to 24–48h (Fig. 2C). As the majority of intracellular cholesterol is localized in the lipid rafts, (25–28) it is not surprising that the profound cholesterol depletion after 6h of 27HC treatment disrupted the steady state organization of cholesterol enriched domains (Fig. 2D–F). Given the disruption of the lipid rafts did not occur when exogenous cholesterol was added (Fig. 2H), it is likely the cholesterol depletion directly interfered with lipid raft function. Impairment of lipid rafts by cholesterol depletion has previously been shown to inhibit membrane bound AKT and IL6-mediated signaling activity in PC cells (20). Herein, we extended these findings to show that impaired lipid raft function, due to cholesterol depletion by 27HC, inhibited signaling pathways such as the IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway. Moreover, 27HC also impaired STAT3 signaling with phenotypic outcomes on cell proliferation, migration/invasion and blocked IL6-induced STAT3 activation. These data suggest that cholesterol depletion not only blocks intracellular oncogenic signaling (AKT) as previously described, but blocks PC cell’s ability to respond to external stimuli (IL-6). Our data are consistent with a previous study in which filipin, a cholesterol-binding compound that disrupts plasma membrane lipid rafts, inhibited IL-6 mediated STAT3 activation in LNCaP cells (25).Together, this helps explain the anti-PC activity of 27HC-mediated cholesterol depletion and provides a clear insight into a key mechanism by which 27HC inhibits PC growth.

STAT3 is frequently activated in many cancer types and is thus regarded as an important therapeutic target (29,31,34). However, clinical trials of STAT3 inhibitors in cancer have not been fruitful in part due to weak on-target activity or potency and unfavorable pharmacokinetics (57). Moreover, we were not able to identify any current trials testing STAT3 inhibitors in men with PC. As such, the finding that 27HC works, in part, via inhibiting STAT3 is novel and suggests that STAT3 may indeed be a viable target in human PC with proper adjuvant therapy. However, the overall modest growth inhibition of 27HC monotherapy seen in the DU145 xenograft model, while significant, argues that 27HC alone is unlikely to be a clinical tool to block STAT3. However, our in vitro data highlights a potential mechanism of sensitization to STAT3 targeted therapies (Fig. 6C). Lastly, it is important to reiterate that we have previously shown non-STAT3 driven PC cell lines and xenograft tumors (i.e. 22RV1) are perturbed by increased levels of 27HC (5). Thus, 27HC-mediated effects likely involve other signaling pathways in addition to IL6-JAK-STAT3. Nonetheless, our findings provide crucial mechanistic insight into how 27HC in part exerts its anti-PC activity.

Regarding developing a therapeutic strategy to treat PC, it is noteworthy that our combination of 27HC and STAT3 inhibitors worked together to both inhibit STAT3 signaling and slow tumor cell growth in vitro with synergistic activity. If validated in future studies, this has important clinical implications. First, it suggests that combination therapies targeting the same pathway may provide better efficacy than single agent drugs – an idea already proven true in PC with dual targeting of the androgen receptor via castration plus the androgen synthesis bio-inhibitor, abiraterone or androgen receptor blocker, enzalutamide. Second, it suggests that novel approaches to targeting STAT3 may succeed where prior single agent STAT3 inhibitors have failed (58). We suggest further research should explore the possibility that 27HC in combination with STAT3 inhibitors may have in vivo anti-PC activity, though this was beyond the scope of the current study, which was focused on the mechanistic understanding of how 27HC exerted its anti PC activity.

It should be noted that like PC, breast cancers exhibit dysregulation of cholesterol and CYP27A1 expression. However, unlike PC, where CYP27A1 and thereby 27HC is frequently lost (5), breast cancers show upregulation of CYP27A1 (44) and thereby increased levels of 27HC. The likely explanation is that 27HC, beyond being an LXR agonist, is also an estrogen receptor (ER) agonist. In this respect, 27HC was described to be an ER ligand that promotes ER+ breast tumor growth (59). Therefore, higher 27HC directly stimulates the estrogen receptor to drive breast cancer growth. This highlights that our findings are likely PC specific and may not apply universally to other cancer types, particularly breast cancer.

Given our data that 27HC suppresses STAT3 activity, one would expect high CYP27A1 (i.e. presumably high intracellular 27HC) tumors to be associated with lower STAT3 activity. However, in a large set of human PC transcriptomes, we found that tumors with high CYP27A1 expression had high STAT3 activation signatures with associations being stronger in high-grade tumors, mCRPC tumors and PCS1 subtype tumors, a subtype of PC that You et. al previously showed was very aggressive (36). This suggests that in these aggressive tumors, STAT3 activation may be a resistance mechanism to retained CYP27A1 expression. Ultimately, more studies using human PC specimens are needed to better understand these interrelationships and importantly to understand which subset of PCs may be sensitive to 27HC and STAT3 inhibition and which may not be.

Our study is not without limitations. While our results were shown in multiple cell lines, we were not able to model the full heterogeneity of PC biology. Thus, it is possible that other PC cell lines and ultimately human PCs behave differently. In addition, alternative formulations and in vivo delivery strategies for improved bioavailability of 27HC would need to be explored given the lipophilic nature of 27HC (partition coefficient logP = 7.1, PubChem CID: 99470). Understanding this heterogeneity and improving 27HC bioavailability will be important for translating these findings to the clinic. Specifically, for future studies combining STAT3 inhibitors and 27HC, identifying biomarkers of sensitivity will be crucial. Finally, though we identified that inhibiting lipid rafts as evidenced by decreased STAT3 activation is one of the key mechanisms by which 27HC exerts its anti-PC activity, there are likely other lipid raft mediate pathways as well as perhaps non-lipid raft mediated effects too. Thus, focused research efforts are needed to fully understand all the mechanisms by which 27HC works in PC cells.

In summary, we demonstrate that 27HC results in rapid cholesterol depletion leading to disruption of lipid raft signaling and specifically inhibits the IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling axis. This provides key mechanistic insight into our prior findings that 27HC inhibits PC cell growth. Future studies are required to explore the clinical implications of these findings for PC therapy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peisch SF, Van Blarigan EL, Chan JM, Stampfer MJ, Kenfield SA. Prostate cancer progression and mortality: a review of diet and lifestyle factors. World J Urol 2017;35:867–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard A, Faeh D, Bopp M, Rohrmann S. Diet and Other Lifestyle Factors Associated with Prostate Cancer Differ Between the German and Italian Region of Switzerland. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2016;86:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diet Wolk A., lifestyle and risk of prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 2005;44:277–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfaqih MA, Nelson ER, Liu W, Safi R, Jasper JS, Macias E, et al. CYP27A1 Loss Dysregulates Cholesterol Homeostasis in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res 2017;77:1662–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allott EH, Farnan L, Steck SE, Song L, Arab L, Su LJ, et al. Statin use, high cholesterol and prostate cancer progression; results from HCaP-NC. Prostate 2018;78:857–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allott EH, Masko EM, Freedland AR, Macias E, Pelton K, Solomon KR, et al. Serum cholesterol levels and tumor growth in a PTEN-null transgenic mouse model of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2018;21:196–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamnagerwalla J, Howard LE, Allott EH, Vidal AC, Moreira DM, Castro-Santamaria R, et al. Serum cholesterol and risk of high-grade prostate cancer: results from the REDUCE study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2018;21:252–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh HY, Leem J, Yoon SJ, Yoon S, Hong SJ. Lipid raft cholesterol and genistein inhibit the cell viability of prostate cancer cells via the partial contribution of EGFR-Akt/p70S6k pathway and down-regulation of androgen receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;393:319–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platz EA, Till C, Goodman PJ, Parnes HL, Figg WD, Albanes D, et al. Men with low serum cholesterol have a lower risk of high-grade prostate cancer in the placebo arm of the prostate cancer prevention trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:2807–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnoeller TJ, Jentzmik F, Schrader AJ, Steinestel J. Influence of serum cholesterol level and statin treatment on prostate cancer aggressiveness. Oncotarget 2017;8:47110–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shafique K, McLoone P, Qureshi K, Leung H, Hart C, Morrison DS. Cholesterol and the risk of grade-specific prostate cancer incidence: evidence from two large prospective cohort studies with up to 37 years’ follow up. BMC Cancer 2012;12:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.YuPeng L, YuXue Z, PengFei L, Cheng C, YaShuang Z, DaPeng L, et al. Cholesterol Levels in Blood and the Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-analysis of 14 Prospective Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24:1086–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swyer GIM. The cholesterol content of normal and enlarged prostates. Cancer Research 1942;2:372–5 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaffner CP. Prostatic cholesterol metabolism: regulation and alteration. Prog Clin Biol Res 1981;75A:279–324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bansal D, Undela K, D’Cruz S, Schifano F. Statin Use and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Plos One 2012;7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Boussac H, Pommier AJC, Dufour J, Trousson A, Caira F, Volle DH, et al. LXR, prostate cancer and cholesterol: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Am J Cancer Res 2013;3:58–69 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krycer JR, Phan L, Brown AJ. A key regulator of cholesterol homoeostasis, SREBP-2, can be targeted in prostate cancer cells with natural products. Biochem J 2012;446:191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pommier AJC, Dufour J, Alves G, Viennois E, De Boussac H, Trousson A, et al. Liver X Receptors Protect from Development of Prostatic Intra-Epithelial Neoplasia in Mice. Plos Genet 2013;9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhuang L, Kim J, Adam RM, Solomon KR, Freeman MR. Cholesterol targeting alters lipid raft composition and cell survival in prostate cancer cells and xenografts. J Clin Invest 2005;115:959–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue S, Li J, Lee SY, Lee HJ, Shao T, Song B, et al. Cholesteryl ester accumulation induced by PTEN loss and PI3K/AKT activation underlies human prostate cancer aggressiveness. Cell metabolism 2014;19:393–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stopsack KH, Gerke TA, Sinnott JA, Penney KL, Tyekucheva S, Sesso HD, et al. Cholesterol Metabolism and Prostate Cancer Lethality. Cancer Res 2016;76:4785–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson ER, DuSell CD, Wang X, Howe MK, Evans G, Michalek RD, et al. The oxysterol, 27-hydroxycholesterol, links cholesterol metabolism to bone homeostasis through its actions on the estrogen and liver X receptors. Endocrinology 2011;152:4691–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu R, Ou Z, Ruan X, Gong J. Role of liver X receptors in cholesterol efflux and inflammatory signaling (review). Molecular medicine reports 2012;5:895–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Adam RM, Solomon KR, Freeman MR. Involvement of cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in interleukin-6-induced neuroendocrine differentiation of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology 2004;145:613–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li YC, Park MJ, Ye SK, Kim CW, Kim YN. Elevated levels of cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in cancer cells are correlated with apoptosis sensitivity induced by cholesterol-depleting agents. Am J Pathol 2006;168:1107–18; quiz 404–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sankaram MB, Thompson TE. Interaction of Cholesterol with Various Glycerophospholipids and Sphingomyelin. Biochemistry-Us 1990;29:10670–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sehgal PB, Guo GG, Shah M, Kumar V, Patel K. Cytokine signaling: STATS in plasma membrane rafts. J Biol Chem 2002;277:12067–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loh CY, Arya A, Naema AF, Wong WF, Sethi G, Looi CY. Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STATs) Proteins in Cancer and Inflammation: Functions and Therapeutic Implication. Frontiers in oncology 2019;9:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santoni M, Conti A, Piva F, Massari F, Ciccarese C, Burattini L, et al. Role of STAT3 pathway in genitourinary tumors. Future Sci OA 2015;1:FSO15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdulghani J, Gu L, Dagvadorj A, Lutz J, Leiby B, Bonuccelli G, et al. Stat3 promotes metastatic progression of prostate cancer. The American journal of pathology 2008;172:1717–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blando JM, Carbajal S, Abel E, Beltran L, Conti C, Fischer S, et al. Cooperation between Stat3 and Akt signaling leads to prostate tumor development in transgenic mice. Neoplasia 2011;13:254–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hafeez BB, Fischer JW, Singh A, Zhong W, Mustafa A, Meske L, et al. Plumbagin Inhibits Prostate Carcinogenesis in Intact and Castrated PTEN Knockout Mice via Targeting PKCepsilon, Stat3, and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Markers. Cancer prevention research 2015;8:375–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Don-Doncow N, Marginean F, Coleman I, Nelson PS, Ehrnstrom R, Krzyzanowska A, et al. Expression of STAT3 in Prostate Cancer Metastases. Eur Urol 2017;71:313–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu P, Wu D, Zhao L, Huang L, Shen G, Huang J, et al. Prognostic role of STAT3 in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2016;7:19863–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.You S KB, Erho N, Alshalalfa M, Takhar M, Ashab HA, Davicioni E, Karnes RJ, Klein EA, Den RB, Ross AE, Schaeffer EM, Garraway IP, Kim J, Freeman MR. Integrated classification of prostate cancer reveals a novel luminal subtype with poor outcome. Cancer Research 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine DM, Haynor DR, Castle JC, Stepaniants SB, Pellegrini M, Mao M, et al. Pathway and gene-set activation measurement from mRNA expression data: the tissue distribution of human pathways. Genome Biol 2006;7:R93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macias E, Rao D, Carbajal S, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J. Stat3 binds to mtDNA and regulates mitochondrial gene expression in keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134:1971–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson BB, Moe PC, Wang D, Rossi K, Trigatti BL, Heuck AP. Modifications in Perfringolysin O Domain 4 Alter the Cholesterol Concentration Threshold Required for Binding. Biochemistry-Us 2012;51:3373–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu S-L, Sheng R, Jung JH, Wang L, Stec E, O’Connor MJ, et al. Orthogonal lipid sensors identify transbilayer asymmetry of plasma membrane cholesterol. Nature Chemical Biology 2017;13:268–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee CD, Sun HC, Hu SM, Chiu CF, Homhuan A, Liang SM, et al. An improved SUMO fusion protein system for effective production of native proteins. Protein Sci 2008;17:1241–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sengupta P, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Skoko D, Renz M, Veatch SL, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Probing protein heterogeneity in the plasma membrane using PALM and pair correlation analysis. Nature Methods 2011;8:969–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwiatek JM, Owen DM, Abu-Siniyeh A, Yan P, Loew LM, Gaus K. Characterization of a new series of fluorescent probes for imaging membrane order. PLoS One 2013;8:e52960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson ER, Wardell SE, Jasper JS, Park S, Suchindran S, Howe MK, et al. 27-Hydroxycholesterol links hypercholesterolemia and breast cancer pathophysiology. Science 2013;342:1094–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y, Gao JL, Ji JW, Gao M, Yin QS, Qiu QL, et al. Cytotoxicity enhancement in MDA-MB-231 cells by the combination treatment of tetrahydropalmatine and berberine derived from Corydalis yanhusuo W. T. Wang. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol 2014;3:68–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu SL, Sheng R, Jung JH, Wang L, Stec E, O’Connor MJ, et al. Orthogonal lipid sensors identify transbilayer asymmetry of plasma membrane cholesterol. Nat Chem Biol 2017;13:268–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin L, Millard AC, Wuskell JP, Dong X, Wu D, Clark HA, et al. Characterization and application of a new optical probe for membrane lipid domains. Biophys J 2006;90:2563–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mora LB, Buettner R, Seigne J, Diaz J, Ahmad N, Garcia R, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 in human prostate tumors and cell lines: direct inhibition of Stat3 signaling induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 2002;62:6659–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark J, Edwards S, Feber A, Flohr P, John M, Giddings I, et al. Genome-wide screening for complete genetic loss in prostate cancer by comparative hybridization onto cDNA microarrays. Oncogene 2003;22:1247–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ichiba M, Nakajima K, Yamanaka Y, Kiuchi N, Hirano T. Autoregulation of the Stat3 gene through cooperation with a cAMP-responsive element-binding protein. The Journal of biological chemistry 1998;273:6132–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narimatsu M, Maeda H, Itoh S, Atsumi T, Ohtani T, Nishida K, et al. Tissue-specific autoregulation of the stat3 gene and its role in interleukin-6-induced survival signals in T cells. Mol Cell Biol 2001;21:6615–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okamoto M, Lee C, Oyasu R. Interleukin-6 as a paracrine and autocrine growth factor in human prostatic carcinoma cells in vitro. Cancer Res 1997;57:141–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haftchenary S, Luchman HA, Jouk AO, Veloso AJ, Page BD, Cheng XR, et al. Potent Targeting of the STAT3 Protein in Brain Cancer Stem Cells: A Promising Route for Treating Glioblastoma. ACS Med Chem Lett 2013;4:1102–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bharadwaj U, Eckols TK, Xu X, Kasembeli MM, Chen Y, Adachi M, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of STAT3 in radioresistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016;7:26307–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murai T. The role of lipid rafts in cancer cell adhesion and migration. Int J Cell Biol 2012;2012:763283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 2015;1:417–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong ALA, Hirpara JL, Pervaiz S, Eu JQ, Sethi G, Goh BC. Do STAT3 inhibitors have potential in the future for cancer therapy? Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2017;26:883–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:352–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu Q, Ishikawa T, Sirianni R, Tang H, McDonald JG, Yuhanna IS, et al. 27-Hydroxycholesterol promotes cell-autonomous, ER-positive breast cancer growth. Cell Rep 2013;5:637–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.