ABSTRACT

A role for the heterotrimeric G protein complex in the induction of a transient burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the Microbial-Associated Molecular Pattern, flg22, a 22-amino acid peptide derived from bacterial flagella, is well established. However, the evidence for a negative or positive role for one component of the Arabidopsis G protein complex, namely, Regulator of G Signaling 1 (AtRGS1) leads to opposing conclusions. We show that the reason for this difference is due to the isolate of Col-0 ecotype used as the wildtype control in flg22-induced ROS and our data further support the idea that AtRGS1 is a negative regulator of the flg22-induced ROS response. Whole-genome genotyping led to the identification and validation of polymorphism in five genes between two Col-0 isolates that are candidates for the different ROS response relative to the rgs1 null mutant.

KEYWORDS: Arabidopsis, flg22, reactive oxygen species (ROS), regulator of G signaling, AtRGS1

A clear role in innate immunity in Arabidopsis for both the canonical and atypical heterotrimeric G protein complex has been demonstrated by several labs.1–6 In Arabidopsis, the canonical G protein complex contains a Gα subunit (AtGPA1) having a crystal structure nearly identical to the animal Gα subunit7 but has different nucleotide-binding properties to the animal counterpart. Invertebrates and some yeast Gα subunits exchange GDP for GTP at an intrinsic low rate that is further catalyzed by 7-transmembrane receptors.8,9 GTP-bound Gα subunits represent the activated state. This GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP with an intrinsic low rate in both plants and animals and this rate is accelerated by Regulators of G Signaling proteins (RGS).10 The GDP-bound state represents the resting state. The G protein complex also contains a Gβγ obligate dimer that plays a critical role in this pathway as evident by the severe pathogen susceptibility phenotypes.6,11 Arabidopsis has a set of three atypical Gα subunits called Extra-Large G proteins (XLG) that do not likely bind or hydrolyze guanine nucleotide in vivo12 yet still interact with AtRGS1 and the Gβγ obligate dimer.12,13 Specifically, XLG2 has an important role in innate immunity.1,14–16 It is also well established that the Arabidopsis complex contains a 7-transmembrane RGS protein called AtRGS1 shown to accelerate the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis rate of AtGPA1.17 Because AtRGS1 accelerates GTP hydrolysis, it is considered a repressor of the active state; however, this is not always clear because the loss of AtRGS1 revealed that it has a positive role in G protein-mediated gene expression.18

Innate immunity is the first line of detection of and defense against pathogens.19 Microbial-Associated Molecular Patterns (MAMPs) shed from both pathogenic and nonpathogenic micro-organism are recognized by plasma membrane receptors and recognition by the plant cell initiates a cascade of molecular events that lead to passive defense mechanisms such as strengthening the barrier and creating a less hospitable environment to the invader such as altering the redox of the microenvironment by the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), a so-called ROS burst. One such MAMP is a 22-amino acid fragment from the bacterial flagellum called flg22.20 flg22 is recognized by its cognate receptor FLS2. The ligated FLS2 forms a complex with its co-receptor BAK1,21 triggering a series of signaling events including the phosphorylation and subsequent endocytosis of RGS1.3

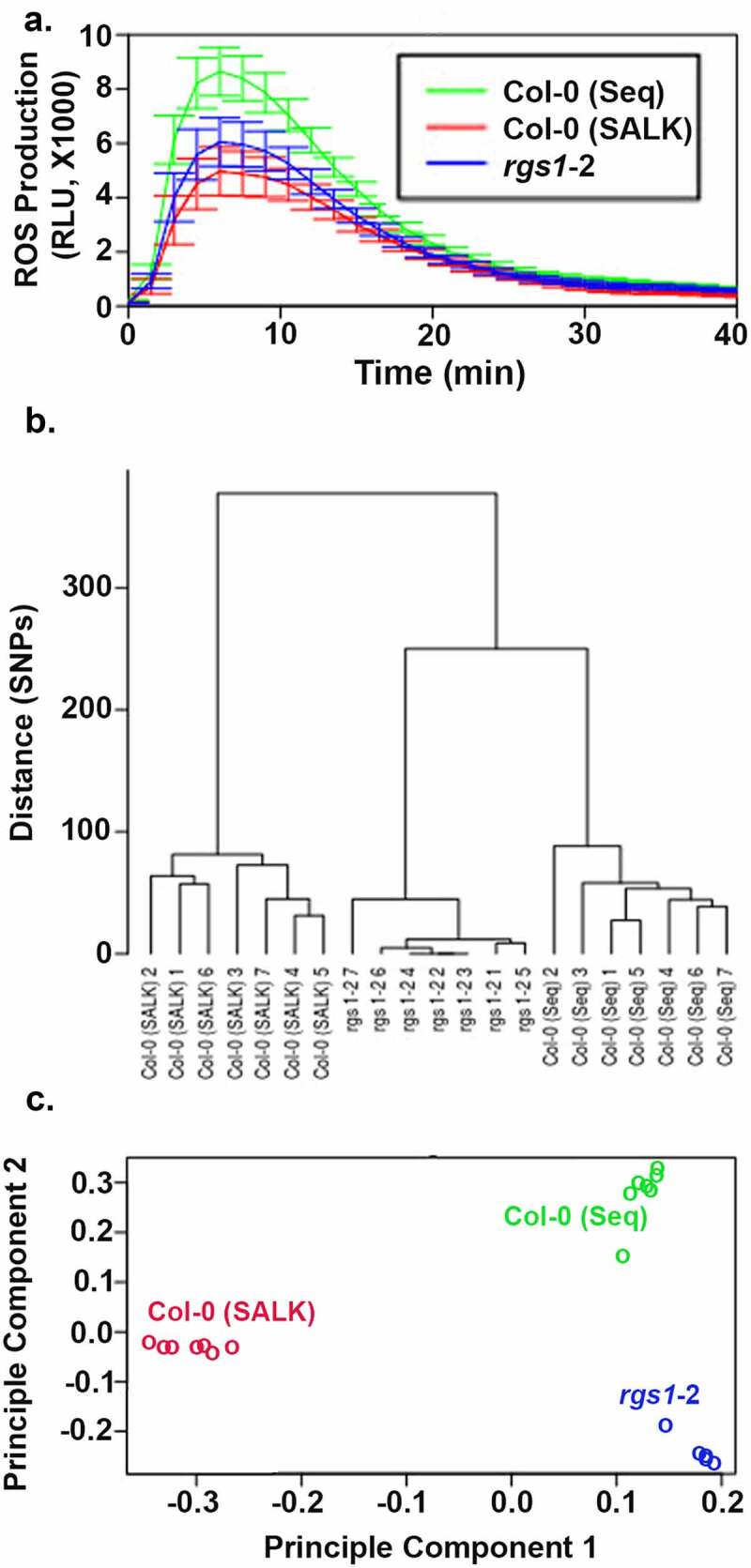

To determine if AtRGS1 plays a role in the flg22-induced ROS burst, Tunc-Ozdemir3 genetically ablated AtRGS1 (rgs1-2) and found unexpectedly that rgs1 mutants had less ROS burst, inconsistent with AtRGS1 serving as a negative regulator. Further complicating the phenotype of the rgs1 mutant is subsequent data from Liang et al.2 showing that the rgs1-2 mutant had a greater flg22-induced ROS burst. The latter report is likely to be correct because this experiment was performed by first backcrossing the rgs1-2 mutant into a Col-0 ecotype and using the segregated wild type and mutant AtRGS1 loci for comparison. The former report used a Col-0 that had not been generated through crosses with the rgs1-2 mutant. Tunc-Ozdemir used a Col-0 line that was sequenced (Col-0 seq) and broadly distributed to the Arabidopsis research community22 including our group. However, the original rgs1-2 line was generated by a pool of Col-0 seeds originating from the Salk Institute (Col-0 Salk) which we obtained for this study. The flg22-induced ROS burst of the rgs1-2 mutants in the JonesLab was compared to the two Col-0 pools (Figure 1a). The newer Col-0 seq isolate showed a greater ROS burst than rgs1-2 as Tunc-Ozdemir reported whereas the original Col-0 Salk pool showed a lesser ROS burst as reported by Liang et al.

Figure 1.

The relative difference in flg22-induced ROS production in the rgs1-2 mutant is dependent on the isolate of the Col-0 ecotype. (a). The Col-0 (Seq) isolate was provided by Sally MacKenzie and described in Shao et al.22 The Col-0 (SALK) isolate was provided by Dr. Jason Reed and described in Alonso et al.23 ROS production over time was monitored by the method of Chung et al.24 Flg22 (100 nM) was added at time zero. The solid lines are the means of 16 individual leaf disks, with the shaded area representing the 95% confidence interval (2 × SEM). This experiment was replicate 3 times with the same results. (b). Dendrogram representing distance among isolates built with the set of markers identified in our variant call analysis; (c). PCA analysis using SNPrelate based on same set of markers

A common approach to analyze the contribution of single genes to quantitative traits is to contrast the values for that trait between a wildtype and a mutant for the gene in the same background as the wildtype. Because A. thaliana is self-fertilizing, and because their wildtype ecotypes are maintained by many generations of selfing, it is often assumed that the batches of WT are highly homozygous and genetically homogeneous. However, if the propagation of WT stocks is not done properly, and because of a de novo haploid single nucleotide mutation rate (6.95 10–9 per site per generation),25 it is possible to introduce genetic variation in the WT lines. We suspect that genetic variation unintentionally introduced in the Col-0 accession is responsible for these disparate phenotypes.

To measure the extent of genetic divergence in rgs1-2 and the two Col-0 isolates from the reference genome and to screen for the genetic variance that may have caused the difference in the ROS burst, we sequenced the genomes of each of seven individuals of rgs1-2 and the two Col-0 isolates. We aligned the reads to the A. thaliana reference genome (TAIR10, https://www.arabidopsis.org/index.jsp) with the bwa mem (version 07.17) package. We marked and removed PCR duplicates using Picard tools (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) and searched for the variants that better distinguish between the 21 lines using the GATK HaplotypeCaller (version 4.1.2.0). We generated genomic variant calling files (GVCF) on each sample individually. Workflow, logic, filtering, and validation of variants are described in detail in Supplemental Information S1. For the identification of strains, we implemented the SNPmatch package.26 The results indicate that all the 21 plants belong to the Col-0 accession with no WS-2 ecotype SNPs detected; WS-2 is a frequent source of contamination,22 Supplemental Information S2. Next, we identified variants that are consistently shared between all the plants of the same line. We found 118 variants (101 SNPs and 17 indels) that were validated with a separate set of data. The validated variants were used for PCA analysis with the SNPrelate package. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) accounted for 51.5% and 33.6% of the total variability originated by the segregation of these 118 alleles between the 21 plants analyzed plants (Figure 1c). Clearly, the three lines are separated in the PC1-PC2 space. PC1 separated Col0 (SALK) from Col-0 (seq) and rgs-1, while PC2 separated Col-0 (seq) from rgs-1. Finally, we applied hierarchical clustering on the validated SNPs to build a dendrogram to represent distances between the different plants, Figure 1b. Thus, in the present report, we identified genetic divergence that separates plants according to their respective lines. It is expected that the presence of genetic polymorphism on loci other than the AtRGS1 gene may have a strong effect on ROS production, explaining the observed discrepancy in the data by Tunc-Ozdemir3 who used Col-0 (Seq) as the wild-type control, and Liang et al.2 who used an isogenic wild-type control. Most importantly, this extra source of genetic variation between mutant and wildtypes seems to overcome the effects of AtRGS1 on ROS production. Thus, whether AtRGS1 is deemed as a negative or positive contributor depends on the Col-0 isolate used as control.

Overall the results (Figure 1a-c) show genetic structure separating the three analyzed lines, indicating that the assumption of population homogeneity between different batches of WT plants or between a single mutant and its WT can lead to inaccurate conclusions. Moreover, we observed that the background of the mutant plant is the one that diverged the most from the reference genome. We do not know how pervasive is this phenomenon with respect to other mutant lines maintained by different laboratories, but we hope our results raise a cautionary red flag when phenotyping mutants and wild-type isolates.

To obtain candidate genes that may be involved in the flg22-induced, AtRGS1-dependent ROS burst, we applied the SNPeffect package to predict phenotypic effects from the detected genetic differences. Supplemental Information S3 lists 44 genes that contain missense and nonsense mutations relative to the Col-0 reference genome for the three genotypes in this study, rgs1-2, Col-0 (Seq), and Col-0 (SALK). Five variants are the same in the two Col-0 isolates and 14 of the remaining 44 genes have mutations different than the reference genome in all three of the genotypes leaving only 25 candidate mutations to explain the difference in ROS burst behavior relative to the wild type. The rgs1-2 mutant shared the reference Col-0 allele in 19 genes and differed in 6 genes. Validation of the variants using individual genomes prepared with deep sequencing eliminated the problem of poor coverage for some of the 21 sequenced genomes leaving five genes (Table 1), specifically a pyruvate metabolism enzyme, a disease resistance protein, a hexose transporter, and 2 transcription factors. There are a large number of SNPs in noncoding regions including promoters, in mitochondrial DNA, and in transposons that cannot be ruled out as the variant that causes this effect on the amplitude of ROS production by flg22.

Table 1.

Validated variant genes between the two Col-0 isolates. See Table S1 for the filtered list of variant genes

| Locus | Gene | Description | Variant to reference genome | Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1G10760 | SEX1 | Pyruvate phosphate dikinase, PEP/pyruvate binding domain-containing protein | Col-0(Seq) | Missense |

| AT1G58400 | Disease resistance protein (CC-NBS-LRR class) family | Col-0(Salk) | Missense | |

| AT3G53960 | Major facilitator superfamily protein | Col-0(Seq) | Missense | |

| AT5G09330 | VNI1, ANAC82 | transcription factor ANAC family | rgs1-2 and Col-0(SALK) | Premature start |

| AT5G50450 | Transcription factor MYND zinc finger family | rgs1-2 and Col-0(SALK) | Start codon lost |

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the NIGMS (GM065989) and NSF (MCB-1713880) to A.M.J. The Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy through the grant DE-FG02-05er15671 to A.M.J. funded the genomic sequencing in this project.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Liang X, Ding P, Lian K, Wang J, Ma M, Li L, Li L, Li M, Zhang X, Chen S, et al. Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins regulate immunity by directly coupling to the FLS2 receptor. eLife. 2016;5:1. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang X, Ma M, Zhou Z, Wang J, Yang X, Rao S, Bi G, Li L, Zhang X, Chai J, et al. Ligand-triggered de-repression of Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins coupled to immune receptor kinases. Cell Res. 2018;28:529–4. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tunc-Ozdemir M, Jones AM.. Ligand-induced dynamics of heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptor-like kinase complexes. Plos One. 2017;12:e0171854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tunc-Ozdemir M, Urano D, Jaiswal DK, Clouse SD, Jones AM.. Direct modulation of heterotrimeric G protein-coupled signaling by a receptor kinase complex. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:13918–13925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C116.736702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu L, Yao X, Zhang N, Gong B-Q, Li J-F. Dynamic G protein alpha signaling in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;516:1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong C-L, Zhang C, Liu J-Z. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling in plant immunity. J Exp Bot. 2019;70:1109–1118. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones JC, Duffy JW, Machius M, Temple BRS, Dohlman HG, Jones AM. The crystal structure of a self-activating G protein α subunit reveals its distinct mechanism of signal initiation. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urano D, Chen J-G, Botella JR, Jones AM. Heterotrimeric G protein signalling in the plant kingdom. Open Biol. 2013;3:120186. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urano D, Jones AM. Heterotrimeric G protein–coupled signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:365–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abramow-Newerly M, Roy AA, Nunn C, Chidiac P. RGS proteins have a signalling complex: interactions between RGS proteins and GPCRs, effectors, and auxiliary proteins. Cell Signal. 2006;18:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urano D, Leong R, Wu T-Y, Jones AM. Quantitative morphological phenomics of rice G protein mutants portend autoimmunity. Dev Biol. 2019;457:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou F, Abramyan TM, Jia H, Tropsha A, Jones AM. An atypical heterotrimeric Gα protein has substantially reduced nucleotide binding but retains nucleotide-independent interactions with its cognate RGS protein and Gβγ dimer. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;3:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urano D, Maruta N, Trusov Y, Stoian R, Wu Q, Liang Y, Jaiswal DK, Thung L, Jackson D, Botella JR, et al. Saltatory evolution of the heterotrimeric G protein signaling mechanisms in the plant kingdom. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra93. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf9558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadota Y, Shirasu K, Zipfel C. Regulation of the NADPH oxidase RBOHD during plant immunity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:1472–1480. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruta N, Trusov Y, Brenya E, Parekh U, Botella JR. Membrane-localized extra-large G proteins and Gβγ of the heterotrimeric G proteins form functional complexes engaged in plant immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:1004–1016. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.255703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu H, Li G-J, Ding L, Cui X, Berg H, Assmann SM, Xia Y. Arabidopsis extra large G-protein 2 (XLG2) interacts with the Gbeta subunit of heterotrimeric G protein and functions in disease resistance. Mol Plant. 2009;2:513–525. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J-G, Willard, F, Huang J, Liang J, Chasse S, Jones, AM, Siderovski DP. A seven-transmembrane RGS protein that modulates plant cell proliferation. Science. 2003;301:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.1087790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grigston JC, Osuna D, Scheible WR, Stitt M, Jones AM. D-glucose sensing by a plasma membrane regulator of G signaling protein, AtRGS1. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3577–3584. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felix G, Duran JD, Volko S, Boller T. Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J. 1999;18:265–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinchilla D, Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Kemmerling B, Nürnberger T, Jones JDG, Felix G, Boller T. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature. 2007;448:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao MR, Shedge V, Kundariya H, Lehle FR, Mackenzie SA. Ws-2 Introgression in a proportion of Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 stock seed produces specific phenotypes and highlights the Importance of routine genetic verification. Plant Cell. 2016. March 15;28(3):603–605. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alonso JM, Stepanova, AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung E-H, El-Kasmi F, He Y, Loehr A, Dangl JL A plant phosphoswitch. platform repeatedly targeted by Type III effector proteins regulates the output of both tiers of plant immune receptors. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weng M-L, Becker C, Hildebrandt J, Neumann M, Rutter MT, Shaw RG, Weigel D, Fenster CB. Fine-grained analysis of spontaneous mutation spectrum and frequency in arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2019;211:703–714. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pisupati R, Reichardt I, Seren Ü, Korte P, Nizhynska V, Kerdaffrec E, Uzunova K, Rabanal FA, Filiault DL, Nordborg M, et al. Verification of Arabidopsis stock collections using SNPmatch, a tool for genotyping high-plexed samples. Sci Data. 2017;4:170184. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]