ABSTRACT

Ebola virus (EBOV) RNA has the potential to form hairpin structures at the transcription start sequence (TSS) and reinitiation sites of internal genes, both on the genomic and antigenomic/mRNA level. Hairpin formation involving the TSS and the spacer sequence between promotor elements (PE) 1 and 2 was suggested to regulate viral transcription. Here, we provide evidence that such RNA structures form during RNA synthesis by the viral polymerase and affect its activity. This was analysed using monocistronic minigenomes carrying hairpin structure variants in the TSS-spacer region that differ in length and stability. Transcription and replication were measured via reporter activity and by qRT-PCR quantification of the distinct viral RNA species. We demonstrate that viral RNA synthesis is remarkably tolerant to spacer extensions of up to ~54 nt, but declines beyond this length limit (~25% residual activity for a 66-nt extension). Minor incremental stabilizations of hairpin structures in the TSS-spacer region and on the mRNA/antigenomic level were found to rapidly abolish viral polymerase activity, which may be exploited for antisense strategies to inhibit viral RNA synthesis. Finally, balanced viral transcription and replication can still occur when any RNA structure formation potential at the TSS is eliminated, provided that hexamer phasing in the promoter region is maintained. Altogether, the findings deepen and refine our insight into structure and length constraints within the EBOV transcription and replication promoter and suggest a remarkable flexibility of the viral polymerase in recognition of PE1 and PE2.

KEYWORDS: Viral transcription and replication, EBOV 3ʹ-leader promoter, expansion of the spacer between PE1 and PE2, RNA stabilization of hairpin structures at the transcription start site (TSS)

Introduction

Ebola virus (EBOV) is an enveloped, non-segmented negative strand (NNS) virus and belongs to the family of Filoviridae in the order Mononegavirales [1]. It is the causative agent of Ebola virus disease (EVD) with fatality rates of ~35 to 80% in humans [2]. Vaccines protecting against EBOV are under development and have been used to help control the spread of EBOV in the recent outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo [3]. However, until now, there is no licenced antiviral treatment available. At the same time there is limited knowledge on the molecular mechanisms of filoviral genome transcription and replication.

The EBOV 19-kb genome comprises seven genes coding for nine mRNAs and proteins (3 GP variants; [4], Fig. 1A). Replication promoters are encoded at the genome’s very 3ʹ- and 5ʹ-ends that are termed 3ʹ-leader and 5ʹ-trailer. The 3ʹ-leader additionally contains signals for transcription initiation, including the transcription start sequence (TSS) of the first gene encoding the nucleoprotein (NP) [5–7]. A relaxed helical nucleocapsid, composed of the viral genome in complex with the viral NP protein, is thought to serve as template for RNA synthesis by the viral polymerase complex L and VP35. In the helical nucleocapsid, 6 RNA residues are bound per NP molecule [8,9]. The viral polymerase L requires VP35 as cofactor which has RNA helicase activity [10] and may support L in gaining access to the template RNA as suggested for other NNS viruses such as mumps virus [11]. For efficient transcription, EBOV additionally requires VP30 [5], a homohexameric phosphoprotein that preferentially binds single-stranded RNA in conjunction with stem-loop structures [12]. Its capability to bind RNA was shown to be a prerequisite for proper transcription activation [13]. However, transcription activation by VP30 is not only dependent on RNA binding but also on a dynamic phosphorylation cycle [14–17].

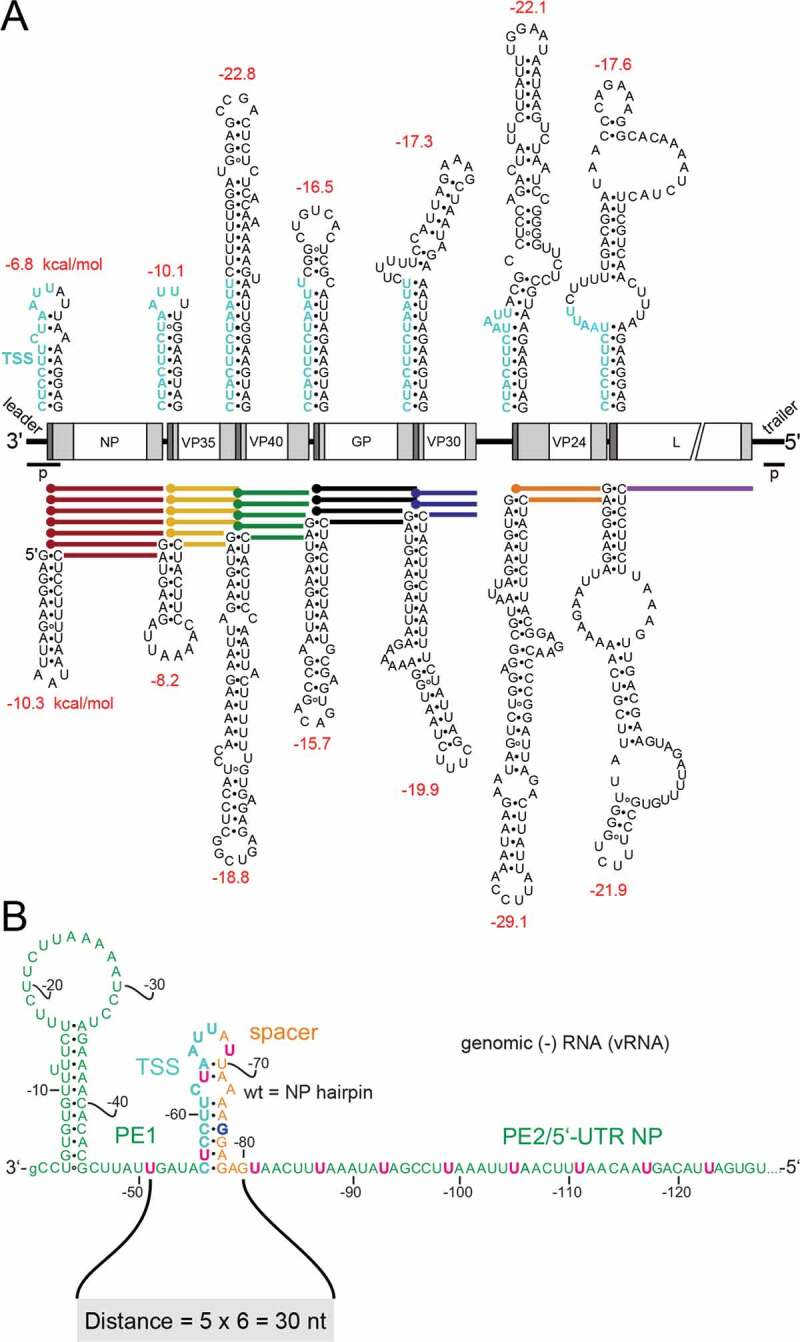

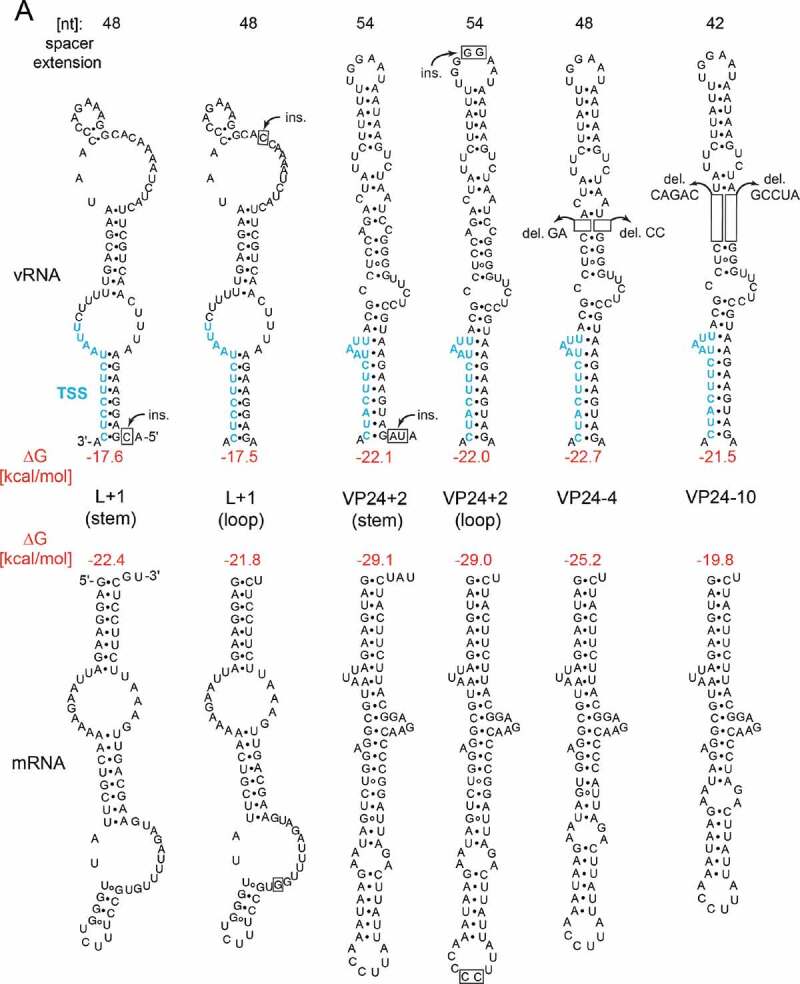

Figure 1.

Secondary structure formation potential at (A) transcription start sites (TSS) of EBOV genes at the genomic (top) and antigenomic (bottom) RNA level and (B) sequence and features of the EBOV 3ʹ-leader promoter. (A) Genomic sequence elements required for transcription (re)initiation are shown in cyan at the top; transcription is initiated opposite to the 3ʹ-terminal C residue in the transcription start signal (TSS). Schematic white boxes in the centre mark the open reading frames for proteins NP, VP35, VP40, GP, VP30, VP24 and L; light grey boxes indicate 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-UTRs, with dark grey areas depicting the position of the predicted secondary structures on the genomic (top) or antigenomic/mRNA level (bottom); p, leader and trailer promoters [42]; mRNAs of the 7 EBOV genes are shown as horizontal coloured lines with terminal dots indicating their 5ʹ-caps. Secondary structures are the minimum free energy (MFE) structures (predicted by RNAfold using the default parameters; http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi). ΔG values, depicted in red above (genomic RNA) or below (mRNA) the structures, were calculated with one extra single-stranded residue included on the 5ʹ-side (genomic RNA) and on the 3ʹ-side (genomic RNA and mRNA) of the stem base. (B) Validated secondary structures forming in naked leader RNA [12,24,25]. Proposed promoter elements 1 and 2 (PE1, PE2) are shown in green letters and the 3ʹ-U residues of UN5 hexamers in PE1 and PE2 are highlighted in pink in the genomic RNA; orange nucleotides mark the spacer region between the TSS (in cyan) and PE2; G-75 is shown in blue to indicate interruption of UN5 hexamer phasing. The distance from nt −51 to −80 (5 x 6 = 30 nt) was recently defined as measure for hexamer phasing between PE1 and PE2 [27]. Nucleotide numbering of the genomic RNA starts at the 3ʹ-terminal nt (position −1) that is complementary to position 1 (5ʹ-terminus) of the antigenome. The 3ʹ-terminal G of the genome is shown as small letter to consider the recent finding that this nucleotide is not essential for initiation, as the EBOV RNA polymerase initiates RNA synthesis at the C residue preceding the 3ʹ-terminal G residue [43]

It is presumed that EBOV transcription follows a start-stop mechanism, recognizing gene start (GS) and gene end (GE) signals at the gene junctions of each EBOV gene and resulting in the synthesis of the individual monocistronic mRNAs. After termination of each transcript at the respective GE signal, the polymerase is thought to either reinitiate mRNA synthesis at the downstream ORF or to dissociate from the template. It is further assumed that the viral polymerase, once dissociated from the template, is only able to re-enter the genome at the 3ʹ-leader promoter. Incomplete reinitiation of transcription at internal genes could explain the lower mRNA levels particularly for the distal VP30, VP24 and L genes, although a so far assumed continuous decline of mRNA levels from the first gene NP to the last gene, as suggested in Fig. 1A, might be questionable based on more recent RNA-seq data [18,19].

Some untranslated regions (UTRs; light grey boxes in Fig. 1A) in the EBOV genome are exceptionally long compared to other viruses of the Mononegavirales [6,20]. To date, the UTR sequences flanking the EBOV ORFs and harbouring the GS and GE signals are considered to be the main regulators of transcription [21,22]. Furthermore, potential stem-loop structures are predicted at the beginning of the 5ʹ-UTRs of all filoviral mRNAs on the genomic and antigenomic RNA level (Fig. 1A) [6,23]. Formation of hairpin (HP) structures in the naked 3ʹ-leader RNA and its antigenomic complement was confirmed by probing experiments [12,24,25].

However, as the genomic and antigenomic RNA are assumed to be mostly encapsidated by NP, secondary structure formation in infected cells may only occur post-transcriptionally on the mRNA level after nascent mRNA transcripts have been released by the viral polymerase (RdRp), or may occur transiently during viral RNA synthesis, for example, when NP proteins have to be removed for threading the template RNA through the active site of the polymerase. The relevance of RNA secondary structure formation to EBOV transcription and replication has not been studied intensively yet. Evidence has been provided that secondary structure formation in the 3ʹ-terminal 45 nt of the genome is not critical for replication [24,26]. However, HP formation at the TSS of the NP gene was reported to regulate the VP30 dependency of viral transcription. This was inferred from the phenotype of a single mutant tested so far. In this 3ʹ-leader mutant, the HP was destabilized, particularly on the mRNA level, which relaxed the VP30 dependency of transcription [25].

The NP HP structure separates promoter elements 1 and 2 (PE1 and PE2) of the bipartite EBOV replication promoter (Fig. 1B) [24]. It was shown that hexamer phasing in this region and the presence of several consecutive 3ʹ-UN5 hexamers in PE2 are crucial for productive replication, which gave rise to formulation of the ‘rule of 6’ in EBOV replication [24]. We recently demonstrated that such hexamer phasing in the 3ʹ-leader is not only important for viral replication but also essential for viral transcription [27]. In addition, UN5 hexamer periodicity was shown to be extendable into PE1, defined by an interspace of 5 × 6 = 30 nt between the genomic 3ʹ-leader positions −51 and −80 (Fig. 1B). We demonstrated that the spacer region (orange nucleotides in Fig. 1B) could be extended to some extent without significant activity losses in transcription and replication of an EBOV minigenome (MG), provided that hexamer phasing was maintained [27]. In the present study, we now explored the limits of spacer length variations and further analysed how stabilization of the potential HP structures at the TSS affects activity of the viral RdRp. We used reporter gene assays as an indirect measure of mRNA synthesis by the EBOV RdRp in combination with qRT-PCR to determine the individual levels of mRNA, genomic RNA (abbreviated as vRNA for viral RNA) and antigenomic RNA (abbreviated as cRNA for complementary RNA) for correlating effects on transcription and replication.

Results

Experimental setup

Here we used a monocistronic replication-competent (RC) MG system, in which the EBOV genes are replaced with a single Renilla luciferase reporter gene. From the plasmid-encoded MG, the co-transfected T7 RNA polymerase synthesizes a genomic vRNA whose 3ʹ-end is generated by a cis-cleaving HDV ribozyme. In addition, plasmids encoding the EBOV proteins NP, VP30, VP35 and L are co-transfected, which are required for viral replication and/or transcription. The viral proteins are expressed by cellular RNA polymerase II and ribosomes in the transfected host cell. The vRNA T7 transcript serves as template for the viral polymerase to synthesize mRNA and cRNA, the latter giving rise to synthesis of new vRNA genomes by the viral polymerase. In this simplified setup, only viral transcription/replication takes place, but no infectious virus-like particles (iVLPs) are formed. An alternative is the use of replication-deficient (RD) MGs, which carry a deletion of the 5ʹ-trailer promoter and thus restrict viral polymerase activity to the synthesis of mRNA and replicative cRNA intermediates only. However, the absolute amounts of viral mRNA are two to three orders of magnitude lower in the RD versus RC MG system (for reasons, see below) [27,28]. As a consequence, the mRNA (and cRNA) levels in the RD MG system are just sufficient for meaningful reporter assay measurements, but too low for reliable qRT-PCR quantification. This is attributable to low viral transcription efficiency on nucleocapsids assembled from vRNA T7 transcripts and coexpressed NP, whereas nucleocapsids assembled during vRNA synthesis by the viral polymerase in the RC MG system are much more efficiently used as templates [27]. In the latter study [27], we demonstrated that effects on reporter activity are qualitatively comparable in the RC vs. RD MG systems, but reliable quantitative analyses using qRT-PCR could not be performed for RD MGs. Thus, we decided here to confine our analyses to the RC MG system, combining reporter activity assays with qRT-PCR quantification of viral mRNA, cRNA and vRNA.

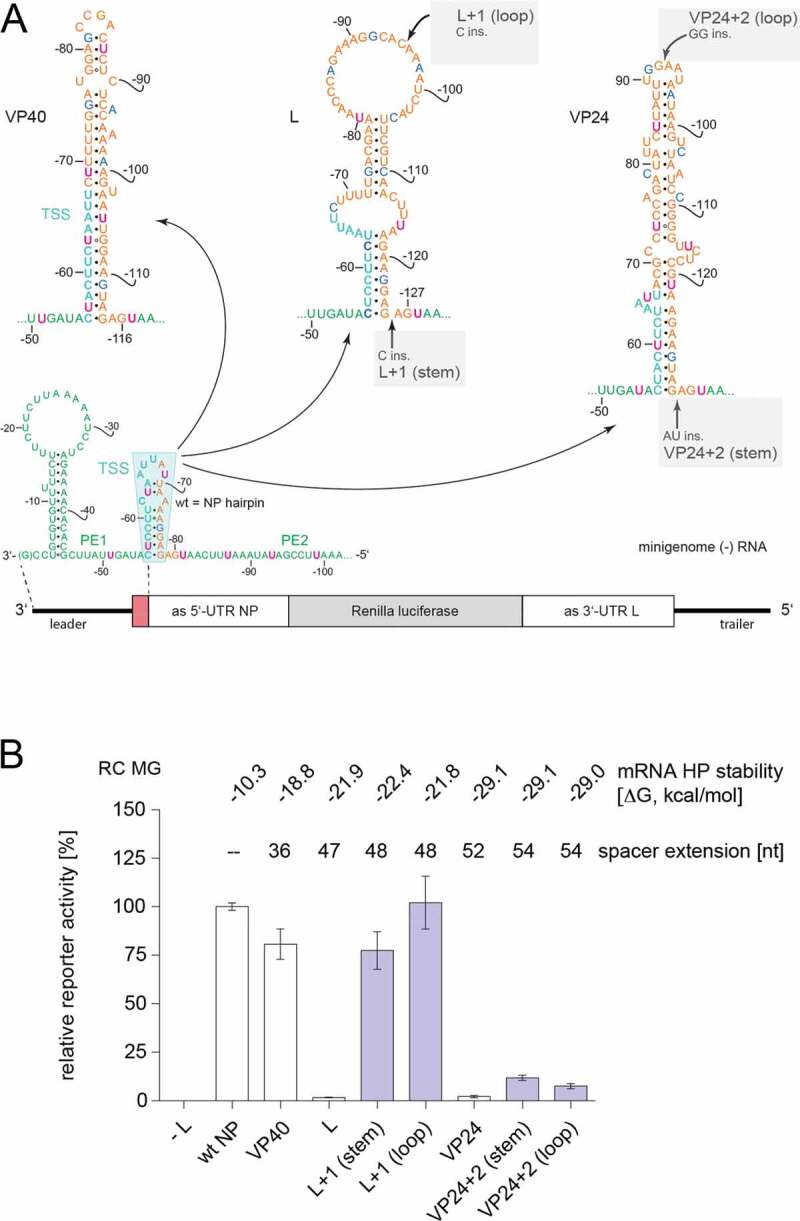

Reporter gene activity is reduced with longer spacers

To deepen our insight into the sequence and structure constraints in the EBOV 3ʹ-leader promoter on viral transcription, we constructed a series of MGs in which we replaced the native NP HP at the transcription initiation region in the 3ʹ-leader with corresponding HP structures derived from internal EBOV genes (see Fig. 1A, 2A). These replacements preserve a functional transcription start sequence (TSS) and basically support viral RNA synthesis as long as hexamer phasing between PE1 and PE2 is maintained (Fig. 1B; 27). As HP structures derived from internal EBOV genes differ from the native NP HP in terms of length and predicted RNA stability on the (-) and (+) RNA level, we have used them as scaffolds to analyse the length and RNA stability constraints in the spacer region between PE1 and PE2 of the 3ʹ-leader promoter. We previously observed that a spacer extension by 36 nt (VP40 HP construct) or 48 nt (L+1 construct; 1 nt inserted to restore hexamer phasing; see Figs. 2A and 3A) give rise to reporter activities similar to those of the MG carrying the native 3ʹ-leader (Fig. 2B). However, constructs VP24+2 (stem) and VP24+2 (loop) (Fig. 2A), although maintaining hexamer phasing due to 2-nt insertions, gave rise to very weak reporter activities [27] (Fig. 2B). As the VP24 constructs introduced the longest spacer expansion of all tested variants (+ 54 nt), we considered that this may be attributable to a length limit for such insertions. Therefore, we restored hexamer phasing in the original VP24 construct by deleting 4 or 10 nt (constructs VP24-4 and VP24-10) instead of inserting 2 nt (Fig. 3A). Indeed, constructs VP24-4 and VP24-10 rescued reporter activity (Fig. 3C); reporter activity for the VP24-4 construct, which extends the spacer region by 48 nt, reached ~75% of that of the wt NP control, thus displaying very similar activity as the L+1 constructs harbouring 48-nt extensions as well (Fig. 3C). Reducing the spacer extension to 42 nt (VP24-10) further enhanced reporter activity to a level at least as high as for the wt NP MG (Fig. 3C). We also noticed that the predicted overall stability on the mRNA level was substantially reduced for the VP24-4 and particularly the VP24-10 variant relative to the VP24+2 constructs, while stabilities on the vRNA level remained rather unchanged (Fig. 3A).

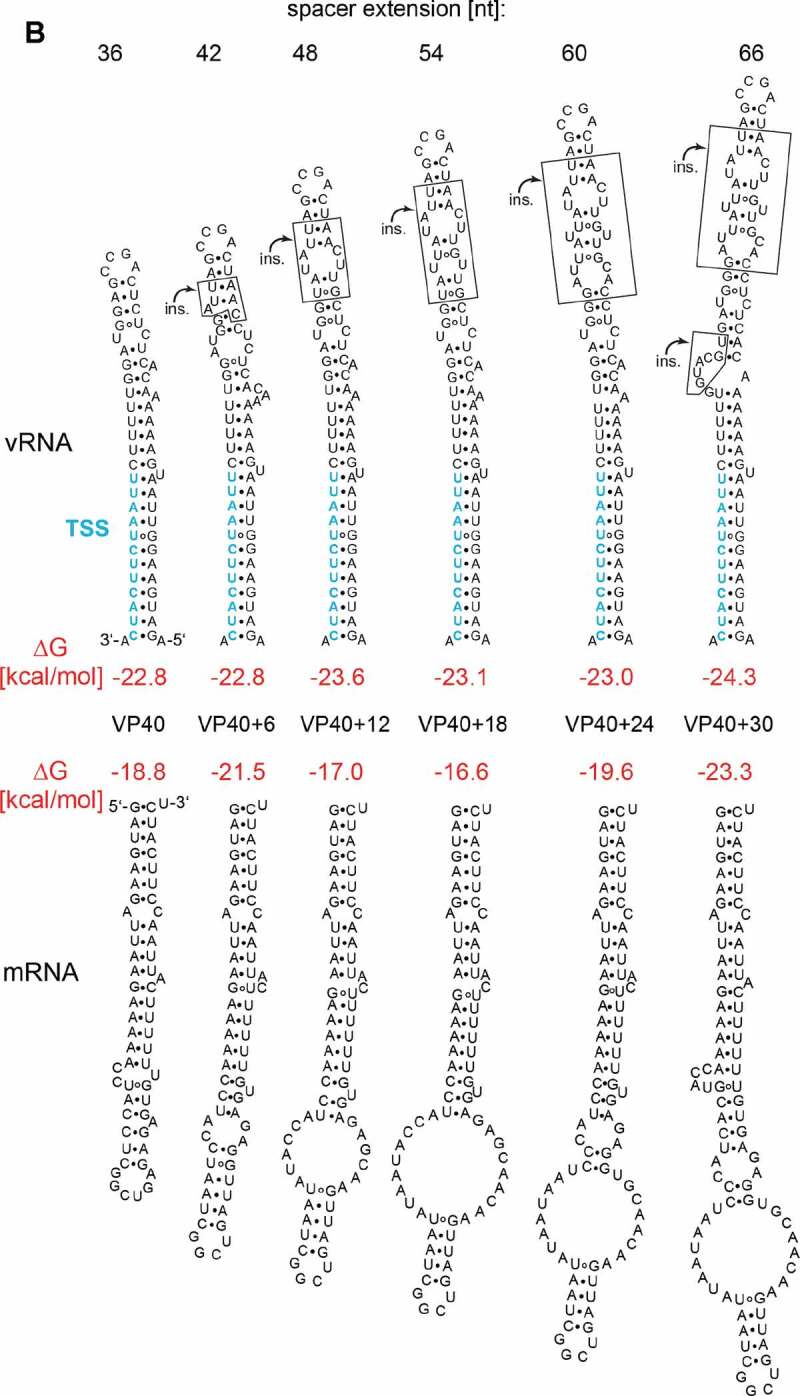

Figure 3.

(Continued)

Figure 3.

(Continued)

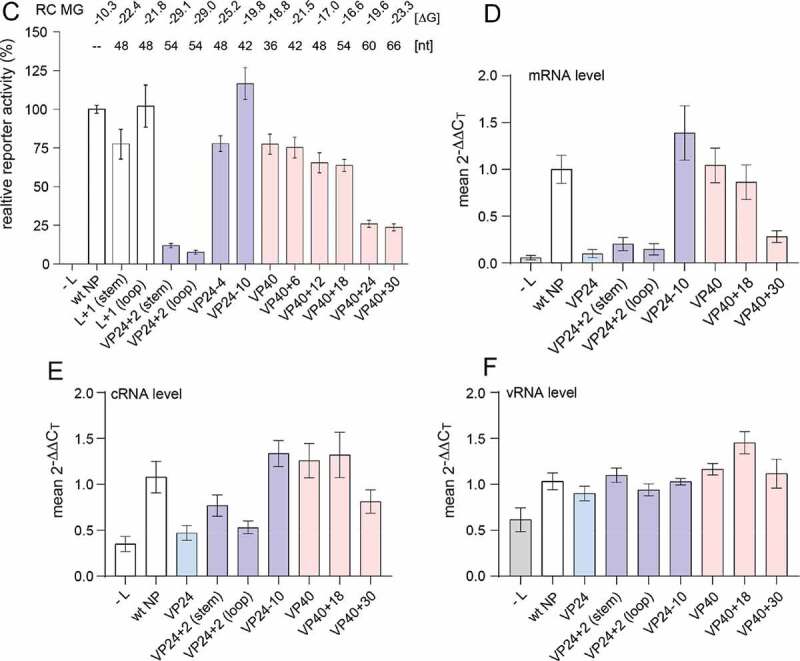

Figure 2.

(A) Illustration of EBOV 3ʹ-leader minigenome constructs (replication-competent) in which the wt NP HP (turquoise-shaded area) consisting of the TSS and the orange spacer sequence was replaced with HP structures derived from the transcription reinitiation sites of the VP40, L and VP24 genes; in the case of the latter two, 1 nt (L) or 2 nt (VP24) were additionally inserted at the indicated locations to restore hexamer phasing between nt −51 and −80 [27]. For further details, see Fig. 1B. (B) Relative reporter activity of replication-competent minigenome (RC MG) constructs specified in panel A. The predicted overall stability of the HP on the mRNA level (MFE structure, RNAfold; for calculation of ΔG values, see legend to Fig. 1A) and the extension of the spacer region relative to the parental wt NP variant is given above the bars. Activity values (± standard error of the mean, SEM) were normalized to the wt NP construct and are based on at least 3 biological replicates with 2 or 3 technical replicates each. – L, background control (transfection without the plasmid encoding the polymerase L); white columns: native 5ʹ-UTR sequences; blue columns: 5ʹ-UTR sequences engineered to obey hexamer phasing

Figure 3.

(A, B) Predicted MFE structures (RNAfold) on the genomic (vRNA, top) and mRNA (bottom) level of (A) engineered L, VP24 and (B) VP40 constructs; ΔG values are indicated in red. The individual spacer extensions (in nt) are given at the top; del., nt deletions; ins., nt insertions. For calculation of ΔG values, see legend to Fig. 1A. (C) Reporter gene activities measured for the replication-competent minigenome (RC MG) constructs specified in panels A and B. Values were normalized to the native (wt NP) 3ʹ-leader as control (100%). – L, background control (specified in the legend to Fig. 2B). Mean values (± SEM) are on average derived from three independent experiments with three technical replicates each. White columns: reference constructs; cyan column: the original VP24 HP construct; blue columns: engineered VP24 HP constructs; pink columns: the parental and engineered VP40 HP constructs. (D-E) Corresponding levels of viral mRNA, cRNA and vRNA measured by a 2-step strand-specific qRT-PCR using total RNA from cells transfected with RC MG constructs as analysed in panel C. For details, see Materials and Methods. Colour code as in panel C and the column for the original VP24 HP shown in light blue

We further scrutinised the length limitation for spacer extensions in the context of the VP40 HP. The VP40 HP has a substantially lower predicted overall stability on the mRNA level (Fig. 3B) than the VP24+2 variants (Fig. 3A), which allowed us to examine the tolerance towards spacer extensions with less potential influence of HP stability. In addition, the VP40 HP, extending the spacer by only 36 nt relative to the wt NP construct, left room for the testing of a broader range of spacer expansions. We elongated the VP40 HP by inserting 6, 12, 18, 24 or 30 nt into its apical part (Fig. 3B). Insertions were designed to change the stability of the respective secondary structures on the vRNA and mRNA level as little as possible. In contrast to the constructs based on the VP24 HP, those derived from the VP40 HP construct showed an increased tolerance towards insertions. The VP40+18 construct, inserting 54 extra nucleotides, still gave ~60% activity, and even for spacer extensions of 60 and 66 nt (constructs VP40+24, VP40+30), reporter activities still reached about ~25% of the wt NP control (Fig. 3C). Thus, we observed a remarkable tolerance of viral RNA polymerase activity to spacer expansions between PE1 and PE2; only insertions exceeding ~60 nucleotides began to considerably attenuate viral transcription. Yet this tolerance was shifted to shorter insertions for TSS/spacer sequences that have the potential to form 5ʹ-terminal mRNA structures of enhanced overall stability, such as the VP24+2 variants.

qRT-PCR reveals low mRNA levels for the VP24+2 constructs

Replication-competent MGs provide an indirect readout of viral transcription. Plasmid-encoded vRNAs, initially transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase in the transfected host cells, yield low levels of functional nucleocapsids with the coexpressed NP protein. Only replicative synthesis of new cRNA and vRNA by the viral polymerase gives rise to the assembly of functionally more competent nucleocapsids that are efficient templates for viral transcription [discussed in 27]. Therefore, low reporter activities can be the result of inefficient mRNA and/or replicative RNA synthesis by the viral RdRp, or inefficient translation of the viral RNA by the cellular translation machinery. To shed more light on the reduced tolerance of the VP24+2 HP constructs towards spacer extensions compared with the VP40 HP series, we directly quantified viral mRNA, cRNA and vRNA derived from cells that were transfected with select MG constructs, using a qRT-PCR setup described previously [27]. This included the VP24 HP MG, one of the least active ones owing to violation of hexamer phasing (Fig. 2B), the highly active VP24-10 variant (Fig. 3C), the VP40 construct and two representative VP40 HP derivative constructs, VP40+18 with still high reporter activity and VP40+30 with reporter activity already decreased to ~25% (Fig. 3C). The analysis revealed a close correlation of reporter activities and mRNA levels, i.e. strongly reduced mRNA levels for the VP24+2 variants followed by variant VP40+30. Likewise, variant VP24-10, exceeding the wt NP construct in reporter activity, also showed highest mRNA levels (Fig. 3D). In conclusion, our findings exclude the possibility that reduced reporter activity of the VP24+2 constructs is due to inefficient mRNA translation and rather indicate that the defect originated from the low production of mRNA by the viral polymerase.

The levels of cRNA were also reduced for the VP24+2 constructs (Fig. 3E), basically mirroring the mRNA graph (Fig. 3D), although associated with higher backgound levels (- L control). The vRNA levels for the VP24+2 constructs almost reached those for the wt NP construct (Fig. 3F), thus disconnecting from the cRNA level (Fig. 3E). We have observed this trend also for other spacer mutants, such as the VP35 HP variant [27]. Two aspects might contribute to this phenotype. On the one hand, there is high background of vRNA levels (- L control) owing to the fact that T7 RNA polymerase transcribes substantial vRNA amounts from the minigenome DNA in transfected cells. In addition, we consider the following scenario: if the 3ʹ-leader promoter is defective/inaccessible, mRNA and cRNA synthesis is impaired because the promoter steers both processes. However, the viral RNA polymerases may become available for increased initiation of vRNA synthesis at the still intact trailer promoter (even if cRNA levels are low). This might cause disproportionately higher vRNA than cRNA synthesis.

A minimal spacer shortened by 12 nt results in substantial levels of viral RNAs

In a reciprocal approach, we introduced a deletion of 12 nt into the wt NP spacer, yielding construct Δ5ʹ-spacer (Fig. 4A). This is the largest possible deletion under the premise of preserving the TSS, leaving PE2 intact and maintaining hexamer phasing. A similar spacer deletion was previously shown to be compatible with EBOV MG replication, but effects on viral transcription were not addressed [24]. The Δ5ʹ-spacer construct is also instrumental to analysing the absence of any potential to form secondary structures at the TSS, neither on the vRNA nor mRNA/cRNA level. This spacer deletion construct still gave rise to profound reporter gene activity, amounting to ~70% of that of the wt NP MG (Fig. 4B). Analysis of viral RNA levels by qRT-PCR revealed reduced levels of mRNA and replicative cRNA. The decrease was 1.75-fold for mRNA, 1.4-fold for cRNA and 1.3-fold for vRNA (Fig. 4C-E). In summary, destroying the HP structure on the genomic and antigenomic/mRNA level by the 12-nt spacer deletion still gave rise to substantial reporter activity and substantial amounts of viral replicative RNAs and mRNAs, although the overall efficiency of the viral polymerase was somewhat decreased relative to the wt NP construct.

Figure 4.

Analysis of a 3ʹ-leader construct with a 12-nt deletion in the spacer region (Δ5ʹ-spacer). (A) Predicted MFE structure of the wt NP transcription start region and the corresponding region of the Δ5ʹ-spacer variant carrying a deletion of 12 spacer nucleotides. The latter variant is predicted to be devoid of any secondary structure on the vRNA and mRNA level. For the nucleotide colour code on the vRNA level, see legend to Fig. 1B. (B) Luciferase reporter activities measured for the Δ5ʹ-spacer construct, the wt NP construct and the wt NP construct in the absence of polymerase L (background control, see legend to Fig. 2B). RC MG, replication-competent minigenome. Mean values (± SEM), normalized to the native wt NP leader construct, are based on 3 biological replicates with 3 or 4 technical replicates each; ****P < 0.00001; (unpaired t test, two-tailed). (C-E) Corresponding levels of viral mRNA, cRNA and vRNA measured by qRT-PCR using total RNA derived from the same cells as in panel B and normalized to the wt NP construct (see Materials and Methods). Mean 2−ΔΔCT values (± SEM) were derived from at least three independent experiments with 3 or 4 technical replicates each; *P < 0.05; *** P < 0.0001; **** P < 0.00001; (unpaired t test, two-tailed; a corresponding Mann Whitney test was used in case of data not normally distributed)

Minigenome replication and transcription are highly sensitive to RNA secondary structure stabilization at the TSS

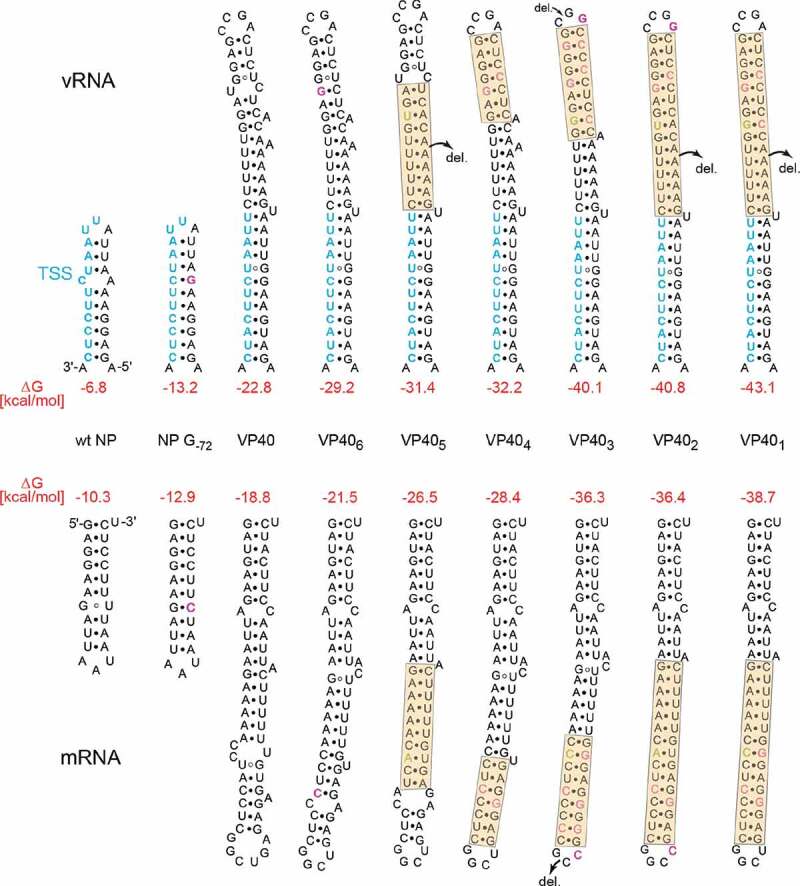

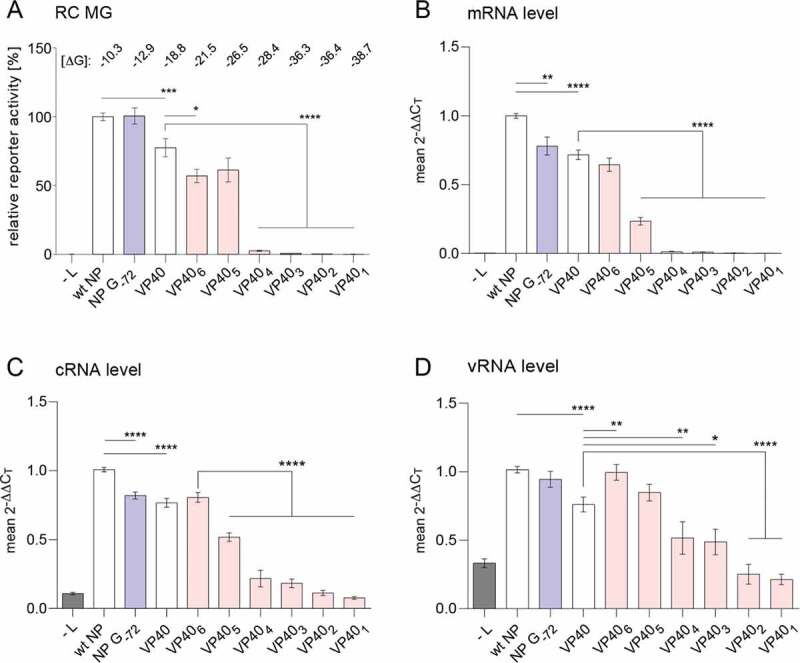

We further explored how stabilization of EBOV HP structures at the TSS influences activity of the viral polymerase complex, again using the VP40 HP construct as platform. We stepwise increased the amounts of G:C and/or A:U base pairs in the hairpin’s upper section (elements highlighted in ochre in Fig. 5) while maintaining hexamer phasing and rendering the lower VP40 stem including the GS sequence (in light blue) unchanged. Minigenomes harbouring these stabilized VP40 hairpin derivatives (termed VP401 to 6) were then analysed for reporter activity as well as mRNA, cRNA and vRNA levels (Fig. 6). For comparison of stabilization effects in different sequence and length contexts, we further included a construct with a stabilized NP G−72 HP (Fig. 5) that was described previously [27]. Here, a G:C base pair was introduced into the NP HP, resulting in an ~1.9-fold and ~1.3-fold HP stabilization on the vRNA and mRNA level, respectively (Fig. 5). The NP G−72 HP construct showed wt-like reporter activity and slightly reduced mRNA and cRNA levels (Fig. 6A-C). For the stabilized constructs VP406 and VP405, we observed ~50 to 60% reporter activity compared with ~80% activity for the original VP40 construct (Fig. 6A). However, mRNA levels in particular as well as cRNA levels were already substantially reduced for construct VP405 relative to the wt NP construct and the original VP40 construct (Fig. 6B, C). Remarkably, a sharp drop almost to background levels was observed for reporter activity and mRNA levels of construct VP404 (Fig. 6A, B). A corresponding decrease in cRNA levels was observed as well (cf. Fig. 6B, C). For the most stable variants, VP402 and VP401, viral RNA levels completely dropped to background levels (Fig. 6B-D).

Figure 5.

Predicted MFE structures (RNAfold) of minigenome constructs encoding the wt NP HP, its stabilized derivative NP G−72, the native VP40 HP and its incrementally stabilized derivatives VP406 to 1; ΔG values (in red), indicated for the vRNA strand (top) and the encoded mRNA (bottom), were calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. Sequence changes relative to the parental VP40 HP are indicated as follows: del., single nt deletions; pink residues, point mutations; green residues, single nt insertions

Figure 6.

Impact of NP HP stabilization and progressive rigidification of the VP40 HP on minigenomic viral transcription and replication. (A) Luciferase activities of replication-competent minigenomes (RC MG) carrying the NP and VP40 variants illustrated in Fig. 5. Activity values are given in % relative to the native 3ʹ-leader [wt NP = 100%]. Mean values (± SEM) are based on 3 biological replicates with at least 3 technical replicates each; *P < 0.05; *** P < 0.0001; **** P < 0.00001 (unpaired t test, two-tailed). (B-D) Corresponding levels of viral mRNA, cRNA and vRNA measured by qRT-PCR of RC MG samples using the same cells as in panel A. Mean values (± SEM) were derived from 3 independent experiments with at least 3 technical replicates each. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.00001; (unpaired t test, two-tailed, a corresponding Mann Whitney test was used in case of data not normally distributed)

Discussion

For some positive-sense RNA viruses such as the hepatitis C virus or the family of coronaviruses, secondary structures, especially at the genomic 3ʹ- and 5ʹ-ends, were shown to be critical regulatory elements influencing viral replication and transcription [29,30]. So far, there is little evidence for RNA secondary structure formation influencing replication or transcription of non-segmented, negative-sense (NNS) viruses. For some single strand RNA viruses, panhandle structures resulting from base pairing of the 3ʹ- and 5ʹ-terminal regions (similar to those formed in genomic segments of influenza A virus) were shown to be relevant for interaction with the viral polymerase [31–35]. Yet, for other NNS viruses, including EBOV, potential RNA secondary structure formation at the genomic 3ʹ-end or panhandle formation owing to pairing of 3ʹ-and 5ʹ-terminal sequences is either unlikely or not relevant to virus replication [24,26,36].

First evidence for a role of RNA structure formation in EBOV transcription came from a study in which the potential NP HP at the first TSS was weakened, primarily on the mRNA level, by introducing several point mutations (generating an NheI restriction site on the DNA level) but without changing the spacer length between PE1 and PE2. This relaxed the VP30 dependency of viral transcription, associated with a trend towards somewhat increased mRNA levels as suggested by Northern blot results [25]. In the present study, we investigated a MG variant lacking any potential to form RNA structures at the TSS on the vRNA and mRNA level (Δ5ʹ-spacer mutant, Fig. 4A). Active and balanced transcription and replication of the Δ5ʹ-spacer construct indicates that RNA secondary structure formation at the TSS is neither obligatory for initiation of RNA synthesis by the EBOV polymerase complex, nor for the balance of transcription and replication, at least in the MG system. However, reporter activity as well as cRNA, vRNA and particuarly mRNA levels were moderately reduced for this construct relative to the wt NP construct (Fig. 4). This may be taken as indication that HP formation at the TSS (either on the genomic and/or antigenomic RNA level) contributes to the overall efficiency of RNA synthesis. Alternatively, the altered spatial relationship of PE1 and PE2 as a consequence of the 12-nt deletion may be the primary reason for moderately attenuated (< twofold) promoter function.

In the present study, we were able to show that both length and potential stability of HP structures in the PE1-PE2 spacer region of the EBOV 3ʹ-leader promoter influence transcription and replication. The TSS of the VP24 gene encodes the longest HP structure among all EBOV genes, with by far the highest predicted overall stability of ΔG ≈ 29 kcal/mol on the mRNA/cRNA level (Fig. 1A). The same pertains to the VP24+2 variants (Fig. 3A) that were constructed to maintain UN5 hexamer phasing [27]. We have shown that low reporter activity of the VP24+2 HP variants is caused by low mRNA synthesis (Fig. 3D). By deleting 4 and 10 nt in the original VP24 construct (variants VP24-4 and VP24-10) to maintain hexamer phasing, we could restore reporter gene activity and mRNA synthesis (Fig. 3C, D). For the VP24-4 construct, overall HP stability on the mRNA level decreased from ca. −29 (VP24+2 variants) to ca. −25 kcal/mol while overall HP stability on the vRNA level was barely changed (even slightly increased relative to all tested VP24-derived constructs) (Fig. 1A, 3A). These observations suggest that incremental HP stabilizations inversely correlate with RNA synthesis efficiency when approaching a critical overall HP stability on the mRNA/cRNA level. This is also in line with our finding that longer spacer extensions were tolerated in the context of the VP40 HP compared with the VP24 HP (Fig. 3C), as all VP40 extension constructs had predicted overall stabilities not exceeding ΔG-values of approx. −23 kcal/mol on the mRNA level (Fig. 3B).

Along the same lines, promoter function began to substantially impair from variant VP406 to VP405 and transcription collapsed with variant VP404 (Figs. 5 and 6). For constructs 6 vs. 5 vs. 4, HP stabilities changed from −29.2 vs. −31.4 vs. −32.2 kcal/mol on the vRNA level and from −21.5 vs. −26.5 vs. −28.4 kcal/mol on the mRNA level (Fig. 5). The activity differences do not correlate well with increases in HP stability on the vRNA level, as variant 4 is predicted to form a HP of very similar stability as variant 5 on the vRNA level (ΔΔG = −0.8 kcal/mol), but is much less active than variant 5. Again, activity losses better correlate with HP stabilization on the mRNA level (ΔΔG = −1.9 kcal/mol). The same conclusion is reached when duplex stability estimates were confined to the upper HP portion that was mutated, where the substantial drop of mRNA levels from variant VP406 to VP405 (Fig. 6B) better correlates with the free energy difference (Fig. S2) on the mRNA (−10.8 vs. −14.1 kcal/mol) than vRNA level (−14.0 vs. −14.6 kcal/mol). Likewise, the apical parts of the VP24+2 HP variants and the VP405 HP have similar predicted stabilities on the mRNA level (Fig. S2), which correlates with comparable mRNA levels in the MG system (Figs. 3D and 6B).

Regarding the steep activity drop of construct VP404 relative to VP406, it is remarkable that we solely converted a C-A mismatch (on the mRNA level) in VP406 to a G:C bp in variant VP404. This mutation generated a continuous helical stretch of 7 bp including 4 G:C bp (Fig. 5, highlighted in ochre) in the apical part of the HP structure. It seems that such continuous helical segments enriched in G:C base pairs and with low positional entropy (Fig. S3) are detrimental to viral RNA synthesis. This opens perspectives to inhibit EBOV transcription and replication by antisense technologies using locked nucleic acids that form particularly stable duplexes with RNA molecules [37].

In conclusion, there is multiple evidence that TSS/spacer sequences, which have the potential to form HP extensions (relative to the wt NP HP) that exceed a certain stability threshold on the mRNA/cRNA level, negatively affect EBOV transcription and replication.

Variant VP405 showed ca. 60% reporter activity, but its mRNA levels were reduced to ~20% relative to the wt NP control, while variant VP406 exhibited ~60% each reporter activity and mRNA level (Fig. 6A, B). This suggests that mRNAs carrying the VP405 HP at the 5ʹ-end are translated with enhanced efficiency, for unknown reasons.

We have found here that the spacer sequence between PE1 and PE2 can be extended by 54 nt without impairing RdRp activity. Only when spacer length extensions reach ≥ 60 nt, reporter activity and mRNA synthesis markedly decreased (~ fourfold; Fig. 3C, D). As deletion of the 12 spacer nucleotides between PE1 and PE2 was also highly compatible with RdRp activity (Fig. 4), our results are not supportive of models developed for paramyxoviruses, according to which the two elements of bipartite promoters (resembling PE1 and PE2 in EBOV) need to be juxtaposed on the same vertical face of the nucleocapsid helix for concerted recognition [for reviews, see 38 and 39]. As discussed before [27], the filoviral RNA polymerase might interact with PE1 and PE2 in a rather flexible manner, being able to loop out spacer insertions or to bend when PE1 and PE2 are connected by a shortened spacer.

Reporter gene activity measured in RC MG systems is determined by viral transcription/replication and translation of viral mRNAs by cellular ribosomes. Thus, extremely low reporter activities seen for constructs VP404 and VP403 (Fig. 6A) could potentially be due to inefficient translation of luciferase mRNA carrying a stabilized 5ʹ-UTR. Yet, the qRT-PCR data verified that viral transcription is defective for these variants (Fig. 6B) despite vRNA levels above background (Fig. 6D). Thus, our findings provide first indirect evidence that predicted hairpin structures do form during viral RNA synthesis and block this process when exceeding a certain degree of stability. One possibility is that VP35 via its recently identified RNA helicase activity [10] unwinds such 5ʹ-UTR structures when they form cotranscriptionally. However, the helicase may become inefficient on extended and rigidified duplex structures.

Finally, the results obtained in the simplified MG system need to be correlated with their effects in the context of the full-length virus. The study presented here, as well as related MG studies, allow us to select from a large variant pool key mutants that appear most appropriate to address specific aspects and constraints of viral RNA synthesis in the full-length EBOV context under BSL4 laboratory conditions.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HEK293 (DMSZ ACC 305) cells were cultivated at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine and 10% FCS (all components from Thermo Fisher Scientific [TFS]). 8 × 105 HEK293 cells were seeded per well (6-well plate, Greiner) containing 3 ml of this medium. Cells were cultivated for 18–24 h as specified above until reaching ~60-80% cell confluency and then transfected with the plasmid mixture described below.

The EBOV-specific minigenome system

The plasmid mixture was composed of plasmids encoding the Zaire EBOV proteins NP (125 ng), VP35 (125 ng), VP30 (100 ng), L (1000 ng), the specific T7 promoter-driven EBOV minigenome variant coding for Renilla luciferase (250 ng), a plasmid encoding T7 RNA polymerase (250 ng), and (optionally) plasmid pGL4.13 (100 ng, Promega) encoding a firefly luciferase used for normalization of transfection efficiencies. For transfection, 6 µl TransIT-LT1 Reagent (Mirus) were added to a premix of 1950 ng plasmid DNA and 200 µl Opti-MEM I Reduced-Serum Medium (TFS). After incubation for 15–30 min at ambient temperature, the mixture was added drop-wise to the HEK293 cells in the well. Reporter activities were measured 48 h post transfection (p.t.) in Renilla and Firefly luciferase assays (both from PJK). The plasmids encoding the EBOV proteins (VP30, NP, VP35 and L) and the T7 RNA polymerase are derivatives of plasmid pCAGGS; those proteins are expressed from the synthetic CAG promoter transcribed by the cellular RNA polymerase II. The EBOV-specific MG plasmid (pANDY 3E5E, [40]) directs synthesis of a negative strand RNA minigenome from a promoter specific for phage T7 RNA polymerase. Plasmids were propagated in the E. coli DH5α strain according to standard microbiological procedures.

Construction of replication-competent (RC) minigenome variants

The native (wt) NP hairpin (Fig. 1) was exchanged or mutated in pANDY 3E5E by Dpn I-based site-directed mutagenesis techniques (Fig. S1) using the primers specified in Table S1. Nucleotide numbers refer to the EBOV Mayinga (Zaire, 1976) sequence, GenBank accession no. AF086833. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Luciferase assay

Cells were lysed in 200 μL 1× Reaction Lysis Buffer (2× Lysis-Juice; PJK). For Renilla luciferase activity measurements, lysates (supernatants after centrifugation) were diluted 1:50 in ddH20, and 10 μl of the diluted lysate were mixed with 50 μL of Renilla luciferase reagent (Renilla-Juice Fluid mixed with coelenterazine substrate in reconstruction buffer according to the manufacturer’s protocol; PJK). For Firefly luciferase activity measurements, 10 μl of undiluted lysate were mixed with 50 μL of Firefly luciferase reagent (Beetle-Juice; PJK). Luciferase activities were measured immediately (Renilla) or 5 s (Firefly) after addition of reagent in a Centro LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies). Renilla luciferase values were normalized to Firefly luciferase values to consider potential differences in transfection efficiency. Results obtained for the minigenome with native 3ʹ-leader were set to 100%.

RNA extraction and purification

Transfected HEK293 cells were harvested at 48 h p.t. and RNA was prepared with the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. This included a first on-column DNase digestion step for 1 h (RNase-Free DNase Set, QIAGEN). After RNA elution in 40 µL RNase-free ddH2O, a second DNase-treatment in solution was performed at 37°C for 1 h in a total reaction volume of 60 µl using Ambion DNase I in the presence of 20 U RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (both from TFS), followed by purification with Roti-Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl alcohol (Carl Roth) and ethanol precipitation. The RNA was redissolved in RNase-free ddH2O.

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Reverse transcription was done as described [27]. In detail, 500 ng RNA were used for reverse transcription (RT) of either negative strand RNA [vRNA, primer luc (+) 5‘-GGC CTC TTC TTA TTT ATG GCG A-3ʹ] or positive strand RNAs [cRNA/mRNA, primer luc (-) 5‘-AGA ACC ATT ACC AGA TTT GCC TGA-3ʹ]. The primer RT_cRNA 5ʹ-CAG TCC TGC CTT TTC TTT TAA TTT TAT C-3ʹ annealing to the cRNA trailer region was used for specific cRNA detection; Firefly luciferase mRNA was reverse-transcribed with the Random Hexamer Primer set (TFS). For the experiments described in Fig. 3D-F, endogenous U6 RNA instead of Firefly luciferase mRNA was used for normalization. U6 RNA was also reverse-transcribed with the Random Hexamer Primer set (TFS). Reactions were performed with the RevertAid H Minus Reverse Transcriptase (TFS) according to the manufacturer’s protocol; this included a denaturation step at 65°C for 5 min as recommended for structured RNAs; cDNAs were diluted 1:10 for quantitative real-time PCR and 2 µL of the diluted cDNA (~5 ng) were used in the respective PCR reaction.

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in a total volume of 10 µL on a QuantStudio3 Real-Time PCR System (TFS) using the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix 2x (TFS). Primers luc (+) and luc (-) were used to amplify vRNA and (+)RNA (cRNA and mRNA), resulting in a 112-bp PCR product. Primers RT_cRNA (see above) and qPCR_cRNA (5ʹ- CGG TGA TAG CCT TAA TCT TTG TG-3ʹ) were used to specifically amplify cRNA (118-bp PCR product), primers qPCR_FF_fwd (5ʹ-CGT GCA AAA GAA GCT ACC G-3ʹ) and qPCR_FF_rev (5ʹ-GGT GGC AAA TGG GAA GTC AC-3ʹ) for Firefly luciferase mRNA (108-bp PCR product). The qPCR primers for U6 cDNA were U6_fwd (5ʹ-GCT TCG GCA GCA CAT ATA CTA AAA T-3ʹ) and U6_rev (5ʹ-ATA TGG AAC GCT TCA CGA ATT TG-3ʹ). PCR reactions followed the manufacturer’s fast cycling mode protocol: Uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) activation at 50°C for 2 min, initial denaturation of cDNA at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 1 s, annealing and extension at 60°C for 30 s.

Quantification and statistical analysis

RNA levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT values method. For each biological replicate of an individual MG construct, CT values from the three technical replicates and two qPCR replicates each (see above) were determined for Firefly luciferase mRNA (or U6 RNA), vRNA, mRNA+cRNA and cRNA. The mean value of the two qPCR replicates was used in the subsequent calculations. For each of the three technical replicates, ΔCT values were calculated by subtracting the Firefly luciferase mRNA or U6 RNA CT value from that of the specific viral RNA. ΔΔCT values were determined by subtracting the mean ΔCT value for the wt NP construct from the ΔCT value of the individual technical replicate of the mutant MG, the – L control or the wt NP MG itself. To calculate mRNA levels, 2−ΔCT values obtained with the specific cRNA primer set were first subtracted from 2−ΔCT values obtained with the cRNA+mRNA primer set. From the set of individual 2−ΔΔCT values (usually 9 values derived from 3 biological replicates with 3 technical replicates each), specific for the MG construct and the viral RNA species, the mean value and the standard error of the mean (SEM) was calculated. For primer efficiency determination based on fluorescence in exponential phase [41], ten independent experiments with three wt NP replicates each were performed for each primer pair. The real-time PCR efficiencies were 1.98 for vRNA and cRNA, 2.00 for (+)RNA (cRNA and mRNA) and 1.96 for Firefly luciferase mRNA. For each qRT-PCR reaction, a ‘minus RT’ control was conducted; in the data evaluation, we only included CT values for which the corresponding ‘minus RT’ CT value was at least seven cycles higher. Data were processed in GraphPad Prism version 8.1.1 for Windows, with statistical details and definition of parameters including P-values defined in the figure legends. Normally distributed samples were analysed by applying the unpaired t test using two-tailed P-values. The nonparametric Mann Whitney test was applied to samples deviating from normal distribution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We like to acknowledge experimental and technical support by Hannes Huber and Astrid Herwig (cell culture) in the initial phase of the project. Financial support by the German Research Foundation (DFG), grant CRC 1021, for project A02 is acknowledged.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [CRC 1021 project A02].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Bukreyev AA, Chandran K, Dolnik O, et al. Discussions and decisions of the 2012–2014 international committee on taxonomy of viruses (ICTV) filoviridae study group, January 2012–June 2013. Arch Virol. 2014;159:821–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Burk R, Bollinger L, Johnson JC, et al. Neglected filoviruses. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2016;40:494–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Malvy D, McElroy AK, de Clerck H, et al. Ebola virus disease. Lancet. 2019;393:936–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mehedi M, Falzarano D, Seebach J, et al. A new Ebola virus nonstructural glycoprotein expressed through RNA editing. J Virol. 2011;85:5406–5414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mühlberger E, Weik M, Volchkov VE, et al., Comparison of the transcription and replication strategies of marburg virus and Ebola virus by using artificial replication systems. J Virol 1999;73:2333–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sanchez A, Kiley MP, Holloway BP, et al. Sequence analysis of the Ebola virus genome: organization, genetic elements, and comparison with the genome of Marburg virus. Virus Res. 1993;29:215–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Chepurnov AA, et al. Characterization of the L gene and 5ʹ trailer region of Ebola virus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sugita Y, Matsunami H, Kawaoka Y, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the Ebola virus nucleoprotein–RNA complex at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature. 2018;563:137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wan W, Kolesnikova L, Clarke M, et al. Structure and assembly of the Ebola virus nucleocapsid. Nat Publ Gr. 2017;551:394–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shu T, Gan T, Bai P, et al. Ebola virus VP35 has novel NTPase and helicase-like activities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:5837–5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cox R, Pickar A, Qiu S, et al. Structural studies on the authentic mumps virus nucleocapsid showing uncoiling by the phosphoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:15208–15213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schlereth J, Grünweller A, Biedenkopf N, et al. RNA binding specificity of Ebola virus transcription factor VP30. RNA Biol. 2016;13:783–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Biedenkopf N, Schlereth J, Grünweller A, et al. RNA binding of Ebola virus VP30 is essential for activating viral transcription. J Virol. 2016;90:7481–7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Biedenkopf N, Lier C, Becker S.. Dynamic phosphorylation of VP30 is essential for Ebola Virus Life Cycle. J Virol. 2016; 90:4914–4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kruse T, Biedenkopf N, Hertz EPT, et al. The Ebola virus nucleoprotein recruits the host PP2A-B56 phosphatase to activate transcriptional support activity of VP30. Mol Cell. 2018;69:136–145.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lier C, Becker S, Biedenkopf N.. Dynamic phosphorylation of Ebola virus VP30 in NP-induced inclusion bodies. Virology. 2017;512:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Takamatsu Y, Krähling V, Kolesnikova L, et al. Serine-arginine protein kinase 1 regulates Ebola virus transcription. mBio. 2020;11(1):e02565-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [18].Albariño CG, Guerrero LW, Chakrabarti AK, et al. Transcriptional analysis of viral mRNAs reveals common transcription patterns in cells infected by five different filoviruses. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shabman RS, Jabado OJ, Mire CE, et al. Deep sequencing identifies noncanonical editing of Ebola and Marburg virus RNAs in infected cells. mBio. 2014;5:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Feldmann H, Mühlberger E, Randolf A, et al. Marburg virus, a filovirus: messenger RNAs, gene order, and regulatory elements of the replication cycle. Virus Res. 1992;24:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Brauburger K, Boehmann Y, Krähling V, et al. Transcriptional Regulation in Ebola Virus: Effects of Gene Border Structure and Regulatory Elements on Gene Expression and Polymerase Scanning Behavior. J Virol. 2015;90:1898–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Neumann G, Watanabe S, Kawaoka Y. Characterization of Ebolavirus regulatory genomic regions. Virus Res. 2009;144:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mühlberger E, Trommer S, Funke C, et al. Termini of all mRNA species of Marburg virus: sequence and secondary structure. Virology. 1996;223:376–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Weik M, Enterlein S, Schlenz K, et al. The Ebola virus genomic replication promoter is bipartite and follows the rule of six. J Virol. 2005;79:10660–10671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Weik M, Modrof J, Klenk H-D, et al. Ebola virus VP30-mediated transcription is regulated by RNA secondary structure formation. J Virol. 2002;76:8532–8539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Crary SM, Towner JS, Honig JE, et al. Analysis of the role of predicted RNA secondary structures in Ebola virus replication. Virology. 2003;306:210–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bach S, Biedenkopf N, Grünweller A, et al. Hexamer phasing governs transcription initiation in the 3ʹ-leader of Ebola virus. RNA. 2020;26:439–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hoenen T, Jung S, Herwig A, et al. Both matrix proteins of Ebola virus contribute to the regulation of viral genome replication and transcription. Virology. 2010;403:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lytle JR, Wu L, Robertson HD. The ribosome binding site of hepatitis C virus mRNA. J Virol. 2002;75:7629–7636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yang D, Leibowitz JL. The structure and functions of coronavirus genomic 3ʹ and 5ʹ ends. Virus Res. 2015;206:120–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Barr JN, Wertz GW. Bunyamwera bunyavirus RNA synthesis requires cooperation of 3ʹ- and 5ʹ-terminal sequences. J Virol. 2004;78:1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Flick R, Hobom G. Interaction of influenza virus polymerase with viral RNA in the “corkscrew” conformation. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2565–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fodor E, Pritlove DC, Brownlee GG. The influenza virus panhandle is involved in the initiation of transcription. J Virol. 1994;68:4092–4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pigott DC. Hemorrhagic fever viruses. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:765–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tomescu AI, Robb NC, Hengrung N, et al. Single-molecule FRET reveals a corkscrew RNA structure for the polymerase-bound influenza virus promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:E3335–E3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hoffman MA, Banerjee AK. Analysis of RNA secondary structure in replication of human parainfluenza virus type 3. Virology. 2000;272:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Grünweller A, Hartmann RK. Locked nucleic acid oligonucleotides. BioDrugs. 2007;21:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].le Mercier P, Kolakofsky D. Bipartite promoters and RNA editing of paramyxoviruses and filoviruses. RNA. 2019;25:279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Noton SL, Fearns R. Initiation and regulation of paramyxovirus transcription and replication. Virology. 2015;479-480:545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Biedenkopf N, Hartlieb B, Hoenen T, et al. Phosphorylation of Ebola virus VP30 influences the composition of the viral nucleocapsid complex: impact on viral transcription and replication. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:11165–11174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Lekanne Deprez RH, et al. Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)data. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339:62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Calain P, Monroe MC, Nichol ST. Ebola virus defective interfering particles and persistent infection. Virology. 1999;262:114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Deflubé LR, Cressey TN, Hume AJ, et al. Ebolavirus polymerase uses an unconventional genome replication mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:8535–8543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.