To the Editor:

Older people are susceptible to the adverse effects of anticholinergic medications, including cognitive impairment.1 A systematic review of observational studies reported mixed associations between high anticholinergic burden, a cumulative measure of anticholinergic medications, and cognitive performance in older people.2 Observational studies may have biased estimates of the impact of exposures, as the exposed and unexposed may systematically differ in covariates associated with the outcomes.3

The inverse probability of treatment weight (IPTW) is a causal method used to adjust exposure effect and mitigate confounding by eliminating the strong influence of imbalanced covariates on the exposure.4 In this context, we examined the association between anticholinergic burden and cognitive function in a nationwide community-dwelling older adult sample using the IPTW method for confounding control.

Methods

Study Population and Procedures

This study was approved by the New Zealand Ministry of Health’s Health and Disability Health Committee (ref 15/CEN/45). We used anonymized data of community-dwelling adults in New Zealand aged ≥65 years who received an interRAI Home Care Assessment System (interRAI-HC) assessment between June 1, 2012, and June 30, 2014. The interRAI-HC instrument has been described in detail elsewhere.5

We used the reference composite anticholinergic scale to identify drugs with anticholinergic properties (DAPs).6 The burden attributable to each DAP anticholinergic medication was calculated and summed for each participant, using the principles of the Drug Burden Index (DBI) equation, DAP-DBI = D/(D+ δ), where D is the participant’s daily dose in milligrams and δ is the minimum efficacious dose.7 We measured anticholinergic burden within 90 days before the first interRAI-HC assessment, and summarized it into 4 categories: DAP-DBI = 0, >0 and ≥1, >1 and ≥2.5, and >2.5. The Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) scores were used to classify the cognition of participants into 4 categories: CPS score 0 and 1 = no cognitive impairment, 2 = mild cognitive impairment, 3 = moderate, and >4 = severe cognitive impairment.

Statistical Analyses

IPTW, the measure used for the inverse weight calculated using the multinomial logistic model, is the probability of having a DAP-DBI of 0, >0 and ≥1, >1 and ≥2.5, and >2.5 within 90 days before the first interRAI assessment. We calculated the odds ratio of having worse cognitive impairment due to DAP-DBI exposure by ordinal regression with and without IPTW weighting. We used the function polr in the R package MASS for the ordinal regression model.

Results

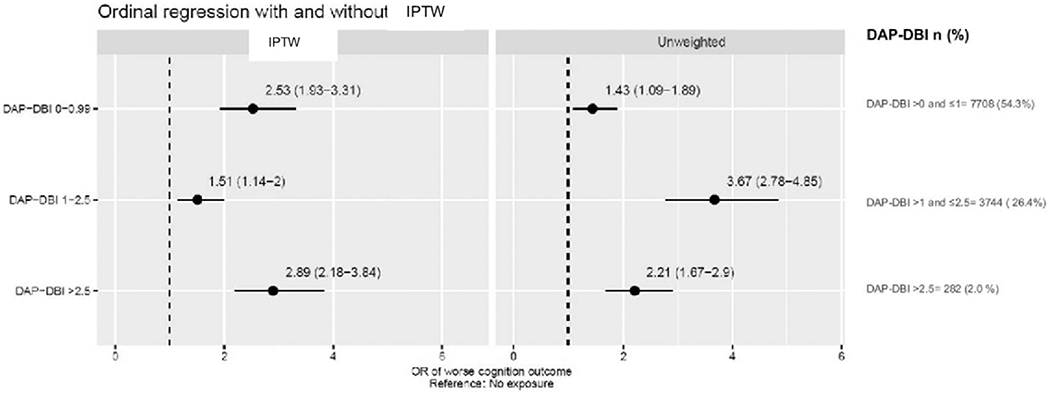

The mean age (SD) of the cohort (N = 14,198) was 82.5 years (7.2); 8866 subjects (62.4%) were female. At baseline, the majority (n = 8148, 57.4%) had no cognitive impairment, 31.7% (n = 4503) had mild cognitive impairment, 7.3% (n = 1033) had moderate cognitive impairment, and a very low proportion (n = 514, 3.6%) had severe cognitive impairment. At baseline, 2464 (17.3%) study participants had a DAP-DBI of 0, 7708 (54.3%) had a DAP-DBI >0 and ≤1, 3744 (26.4%) had a DAP-DBI >1 and ≤2.5, and 282 (2.0%) had a DAP-DBI >2.5. After IPTW adjustment, baseline characteristics were balanced (population standardized bias < 0.20 for all variables and in all DAP-DBI categories).8 The IPTW-adjusted ordinal regression model showed a significant association of poor cognitive performance with anticholinergic burden. The odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) were as follows: 2.53 (1.93, 3.31) for DAP-DBI >0 and ≤1,1.51 (1.14,1.20) for DAP-DBI >1 and ≤2.5, and 2.89 (2.18, 3.84) for DAP-DBI >2.5, compared to those with zero DAP-DBI (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Ordinal regression with and without IPTW. Values are odds ratios (ORs), with the 95% confidence intervals within parentheses.

Discussion

This study found an association between anticholinergic exposure and cognitive performance, which is consistent with 2 large cohort studies.9,10 In comparison, a methodologic improvement of the current study is the use of the IPTW method to diminish bias due to confounding factors that dictate exposures. Although the cross-sectional design limited its temporality, our study has several strengths, including its large size, balancing cohort characteristics, nationwide coverage, use of an internationally recognized instrument for geriatric risk assessment, and adaptation of a validated pharmacologic model to quantify the anticholinergic burden.

The reference composite anticholinergic scale identifies several DAPs that are not included in the validated DBI and may be appropriate therapeutic options for comorbid conditions that are risk factors for cognitive impairment. Furthermore, the lack of dose-response seen in our study suggests that exposure to DAPs that cross the blood-brain barrier may be appropriate for further investigation. Despite confounding control, this observational study only shows associations, and the findings do not infer causality.

Conclusions and Implications

High anticholinergic burden was associated with poor cognitive performance. Anticholinergic burden is a modifiable risk factor and should be routinely targeted during geriatric risk assessments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National interRAI services for providing access to the interRAI-HC data.

H.A. was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG047891-01A1, P50AG047270, and P30AG021342-16S1); in addition, H.A. and L.H. received support from the National Institute on Aging Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG021342).

Contributor Information

Prasad S. Nishtala, Department of Pharmacy & Pharmacology, University of Bath Bath, United Kingdom.

Heather Allore, Department of Biostatistics, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT; Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Ling Han, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Hamish A. Jamieson, Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand; Burwood Hospital, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Sarah N. Hilmer, Kolling Institute, Royal North Shore Hospital and Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Te-yuan Chyou, Department of Biochemistry, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

References

- 1.Ruxton K, Woodman RJ, Mangoni AA. Drugs with anticholinergic effects and cognitive impairment, falls and all-cause mortality in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;80:209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kersten H, Molden E, Tolo IK, et al. Cognitive effects of reducing anticholinergic drug burden in a frail elderly population: A randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34: 3661–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schluter PJ, Ahuriri-Driscoll A, Anderson TJ, et al. Comprehensive clinical assessment of home-based older persons within New Zealand: An epidemiological profile of a national cross-section. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016;40: 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salahudeen MS, Duffull SB, Nishtala PS. Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayan SW, Hilmer SN, Horsburgh S, et al. Anticholinergic component of the Drug Burden Index and the Anticholinergic Drug Scale as measures of anticholinergic exposure in older people in New Zealand: A Population-level Study. Drugs Aging 2013;30:927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA, Almirall D, et al. A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Stat Med 2013;32:3388–3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox C, Richardson K, Maidment ID, et al. Anticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:1477–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lechevallier-Michel N, Molimard M, Dartigues JF, et al. Drugs with anticholinergic properties and cognitive performance in the elderly: Results from the PAQUID Study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;59:143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.