Abstract

Background

The epidemiology of Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILD) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is presently unknown.

Research question

Describe the incidence/prevalence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of ILD patients within the Veteran’s Administration Mid-Atlantic Health Care Network (VISN6).

Study design and methods

A multi-center retrospective cohort study was performed of veterans receiving hospital or outpatient ILD care from January 1, 2008 to December 31st, 2015 in six VISN6 facilities. Patients were identified by at least one visit encounter with a 515, 516, or other ILD ICD-9 code. Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using median, 25th and 75th percentile for continuous variables and count/percentage for categorical variables. Characteristics and incidence/prevalence rates were summarized, and stratified by ILD ICD-9 code. Kaplan Meier curves were generated to define overall survival.

Results

3293 subjects met the inclusion criteria. 879 subjects (26%) had no evidence of ILD following manual medical record review. Overall estimated prevalence in verified ILD subjects was 256 per 100,000 people with a mean incidence across the years of 70 per 100,000 person-years (0.07%). The prevalence and mean incidence when focusing on people with an ILD diagnostic code who had a HRCT scan or a bronchoscopic or surgical lung biopsy was 237 per 100,000 people (0.237%) and 63 per 100,000 person-years respectively (0.063%). The median survival was 76.9 months for 515 codes, 103.4 months for 516 codes, and 83.6 months for 516.31.

Interpretation

This retrospective cohort study defines high ILD incidence/prevalence within the VA. Therefore, ILD is an important VA health concern.

Introduction

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a rare group of heterogeneous respiratory disorders characterized by progressive infiltration of the interstitium by immune cells and matrix producing fibroblasts, ultimately leading to development of fibrosis. While idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is associated with the most substantial morbidity and mortality among ILDs, the epidemiology of others that are environmentally associated or secondary to other systemic diseases is less frequently studied. The morbidity and mortality of ILD is dependent on the specific ILD subtype. World Health Organization data of males diagnosed with IPF in the European Union (EU) defined the median mortality at 3.75 per 100,000 people in the EU from 2001–2013 [1]. Additionally, the individual economic impact of ILD is substantial, as analysis of USA Medicare claims showed the total direct cost for patients with IPF was $26,000/person-year between 2001–2008, and the incremental cost over control subjects was $12,124 [2]. Despite the clear impact of ILD on human health [3] and the ongoing efforts to define clinical characteristics, there remain considerable deficits in our understanding of the incidence and prevalence of ILD across various groups.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is one such group where there is a gap in knowledge about epidemiology of ILD. The VHA is the largest integrated health system in the USA and has led epidemiology efforts in other disease processes such as diabetes [4], coronary disease [5], and hypertension [6]. The VA healthcare database, as of 2017, contains more than 9 million subjects [7] and is enriched with older males with smoking histories, which are known risk factors for increased ILD incidence. Based on this, it has been hypothesized that ILD is more prevalent in veterans’ populations. However, to our knowledge there have been no large epidemiological studies on ILD in veterans.

The primary objective of this study is to describe the incidence/prevalence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of patients with ILD who received care within the Veteran’s Administration Mid-Atlantic Health Care Network.

Methods

This was a multi-center retrospective cohort study including patients who received inpatient or outpatient ILD care from January 1, 2008 to December 31st, 2015 at six VHA medical facilities and associated clinics in North Carolina (Asheville, Durham, Fayetteville, Salisbury) and Virginia (Richmond, Salem). Subjects were identified by any single visit encounter coded with either a 515, 516, or other ILD ICD-9 code (135, 501, 508.1, or 518.89) (S1 Table). The selection of these codes was based on a review of the available ILD ICD-9 diagnostic codes. During the study period on 10/01/2015 there was a transition to ICD-10 coding. ICD-10 codes were not used to capture patients during this study period. There were no exclusion criteria. This study was reviewed and approved by the Durham VA Institutional Review Board (IRB #01882/001). The study was performed under a waiver of consent and a waiver of HIPPA as approved by the IRB. Under the approved protocol, the study team had access to patient identifiers during the performance of the electronic record review. During data extraction performed for the analysis, the data was anonymized and no individual patient identifiers are reported in this study.

Data abstraction used data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and other electronic medical record (EMR) sources, including VistaWeb. CDW data included demographics, site of visits, ICD-9 diagnostic codes to include pre-selected comorbidities, and dates of procedures (pulmonary function tests, bronchoscopies, radiographs, and surgical procedures). EMR data included smoking history, ILD diagnostic information including thoracic computed tomographic (CT) scans, bronchoscopies, and surgical biopsies, pulmonary function tests, and drug therapies. To supplement CDW data, an ILD specialist, pulmonary specialty pharmacist, and a pulmonary fellow performed EMR abstractions. The ICD-9 diagnosis was confirmed based on a thorough chart review. The data from this chart review included physician notes, and CT scan reports. This was reviewed by the study team to confirm or refute the diagnosis. A random sample of charts (10% of total) were re-reviewed by a separate member of the research team to confirm chart abstraction quality. In instances where patients were coded with both 515 and 516 codes, the study team used the physician notes, exam, laboratory values and CT scan report to clarify which of the ICD-9 codes were accurate and this was then used to define their ICD-9 group. Subject data was collected through January 2019 from the time of first ILD diagnosis until their last visit to the facility, death, lung transplantation, or lost to follow-up. Initial diagnosis date was reviewed and updated if it was earlier than captured in the time range.

The pattern of baseline PFTs using spirometry and DLCO measures were categorized as: 1) restrictive: forced vital capacity (FVC) < 80%; forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/FVC > 70%); 2) obstructive: FEV1/FVC ≤ 70%; 3) Isolated DLCO Impartment: FVC > 80%, FEV1/FVC > 70%, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) ≤ 80%); and 4) normal: FVC > 80%, FEV1/FVC > 70%, DLCO > 80%.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using median, 25th and 75th percentile for continuous variables and count and percentage for categorical variables. Broad and narrow case definitions were defined. Broad included any individual with an ILD diagnostic code, while narrow required an ILD diagnostic code with evidence of a HRCT scan or a bronchoscopic or surgical lung biopsy. Characteristics were summarized, stratified by ICD-9 code of ILD diagnosis and presence or absence of computed tomography of the chest, surgical biopsy, or transbronchial biopsy and differences were compared using Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Incidence per 100,000 patients was calculated as the number of subjects diagnosed with an ILD in each year divided by the number of unique patients who visited one of the VA centers in that calendar year. Incidence rates were averaged across years. Date of diagnosis was based on the date of physician note or radiologic study identifying and ILD. Though subjects were initially identified by and ICD-9 billing code from 2008–2015, chart review information was used to define the date of diagnosis and therefore could have been prior to 2008. Prevalence per 100,000 patients was calculated as the number of patients diagnosed with an ILD before December 31st, 2015 and still alive at this date, divided by the number of unique patients who visited one of the VA centers in 2013–2015 and were alive as of December 31st, 2015 (as an estimate of the number of VA patients in the system at these centers). Kaplan-Meier curves were generated based on ICD-9 diagnosis codes. The curves were based on any recorded mortality in the study population through January 2019 when the database collection stopped. A log-rank test was used to test the differences in survival among groups. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A p-value <0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

We identified 3293 subjects in our cohort who met our inclusion criteria. S1 Fig illustrates the breakdown of the subjects into “No ILD, 515 ICD 9, 516 ICD 9, or Other ILD” following EMR review. Baseline characteristics for the total population (including the “No ILD” category) are noted in S2 Table. The median age was 69 years-old with a wide age distribution. The majority of individuals are male (96%), white (79%) and current or former smokers (75%). The median BMI was 27.8, with 39% of the population considered overweight and 35% obese. Co-morbid diseases were frequently observed in the cohort. Airway disease was the most frequent reported with chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD; 41%) and asthma (8%) documented in 49% overall. Consistent with this, 29% of the cohort had spirometric obstruction. Interestingly, 65% of total cohort did not have pulmonary function testing recorded in the EMR. Gastroesophageal reflux disease was also a frequent comorbidity, recorded in 40% of subjects. Lung cancer and mixed connective tissue disease were noted at 8% and 1%, respectively.

Review of the available clinical information in the EMR determined that 879 subjects (26%) had no radiologic or clinical evidence of ILD. Given that this represented a large portion of the cohort, Table 1 segregates characteristics by individual ICD-9 code from those who had no evidence of ILD. The vast majority of subjects had an ICD-9 515 code (47%). Clinical characteristics between the ICD-9 groups were similar, with the exception of COPD, where 49% of 515 coded subjects having this co-morbidity versus only 39% in the 516 grouping. This was reflected in the 515 group spirometry, as they had an increased percentage of individuals with obstruction when compared to the 516 group. Alternatively, the 516 group predominantly exhibited a restrictive spirometric pattern. Subjects with no documented ILD on chart review had similar characteristics to those with ILD except for lower rates of smoking (29% never smokers) and COPD (30%). As the 516 ICD code included several sub-groupings, we stratified by individual 516 ICD subset (S3 Table). Within the 516 group, the majority (81.1%) were coded as 516.31 (Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis), or 516.8 (Other specified alveolar and parietoalveolar pneumonopathies). Interestingly, minimal differences existed in the clinical characteristics or co-morbidities between these 516.31 or 516.8 groupings.

Table 1. Characteristics of patient population stratified by ICD-9 code.

| 515 (N = 1552) | 516 (N = 742) | No ILD (N = 879) | Other ILD (N = 120) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 69 (62, 78) | 69 (62, 79) | N/A | 68 (63, 76) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 65 (4%) | 23 (3%) | 46 (5%) | 7 (6%) |

| Male | 1487 (96%) | 719 (97%) | 833 (95%) | 113 (94%) |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 253 (16%) | 110 (15%) | 142 (16%) | 20 (17%) |

| White | 1212 (78%) | 592 (80%) | 703 (80%) | 97 (81%) |

| Hispanic | 8 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 8 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 15 (1%) | 8 (1%) | 3 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Not Reported | 64 (4%) | 25 (3%) | 23 (3%) | 2 (2%) |

| BMI | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 27.7 (24.7, 31.7) | 27.5 (24.7, 30.7) | 28.3 (25.1, 32.6) | 28.8 (25.1, 32.3) |

| BMI–categorized | ||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 425 (27%) | 207 (28%) | 215 (25%) | 28 (24%) |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 585 (38%) | 316 (43%) | 328 (37%) | 39 (33%) |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 540 (35%) | 219 (30%) | 334 (38%) | 51 (43%) |

| Smoker | ||||

| Current | 321 (21%) | 125 (17%) | 169 (19%) | 18 (15%) |

| Ever | 910 (59%) | 468 (63%) | 399 (45%) | 76 (63%) |

| Never | 258 (17%) | 124 (17%) | 259 (29%) | 21 (18%) |

| Not Reported | 63 (4%) | 25 (3%) | 52 (6%) | 5 (4%) |

| COPD | 755 (49%) | 291 (39%) | 263 (30%) | 54 (45%) |

| Asthma | 117 (8%) | 49 (7%) | 82 (9%) | 6 (5%) |

| Lung cancer | 110 (7%) | 58 (8%) | 59 (7%) | 23 (19%) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 620 (40%) | 283 (38%) | 363 (41%) | 40 (33%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 515 (33%) | 298 (40%) | 250 (28%) | 43 (36%) |

| Coronary heart failure | 282 (18%) | 137 (18%) | 108 (12%) | 19 (16%) |

| Stroke | 172 (11%) | 84 (11%) | 68 (8%) | 11 (9%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 575 (37%) | 282 (38%) | 306 (35%) | 35 (29%) |

| Obesity | 292 (19%) | 103 (14%) | 205 (23%) | 28 (23%) |

| PFT group | ||||

| Not Reported | 829 | 391 | 879 | 56 |

| 1. Restrictive | 347 (48%) | 211 (60%) | 0 (0%) | 35 (55%) |

| 2. Obstructive | 245 (34%) | 71 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (23%) |

| 3. Isolated DLCO Impairment | 108 (15%) | 63 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (19%) |

| 4. Normal | 23 (3%) | 6 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) |

Table 2 reports the differences in clinical care of subjects stratified by ICD code. Overall, the cohort had relatively high rates of high-resolution CT scans performed across both 515 and 516 ICD-9 codes (>79%). Subjects with 515 and 516 codes had similar, but low, rates of bronchoscopy. Across all groups, there were low rates of transbronchial or surgical lung biopsies performed. There was moderate usage of oxygen therapy, which increased from initial diagnosis to the last recorded visit. There was a moderate use of corticosteroids and low rates of IPF therapy use across the cohort.

Table 2. Clinical care characteristics stratified by ICD-9 code.

| 515 (N = 1552) | 516 (N = 742) | No ILD (N = 879) | Other ILD (N = 120) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Had a high resolution CT scan | 1347 (87%) | 589 (79%) | 637 (73%) | 110 (92%) | <0.0011 |

| Bronchoscopy | 119 (8%) | 73 (10%) | 28 (3%) | 24 (20%) | <0.0011 |

| Biopsy type | <0.0011 | ||||

| Not Reported | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Surgery | 82 (5%) | 94 (13%) | 38 (4%) | 9 (8%) | |

| TBBX | 76 (5%) | 47 (6%) | 23 (3%) | 12 (10%) | |

| Oxygen therapy at diagnosis | 252 (16%) | 165 (22%) | 36 (4%) | 18 (15%) | <0.0011 |

| Oxygen therapy at last visit | 629 (41%) | 436 (59%) | 173 (20%) | 47 (39%) | <0.0011 |

| PPI drug | 942 (61%) | 454 (61%) | 510 (58%) | 79 (66%) | 0.2851 |

| Corticosteroid drug | 758 (49%) | 334 (45%) | 268 (30%) | 51 (43%) | <0.0011 |

| Antifibrotic drug | 18 (1%) | 46 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | <0.0012 |

1Chi-Square

2Fisher Exact

ICD- International Classification of Diseases; ILD–Interstitial Lung Disease; TBBX–Transbronchial Biopsy; PPI–Proton Pump Inhibitor

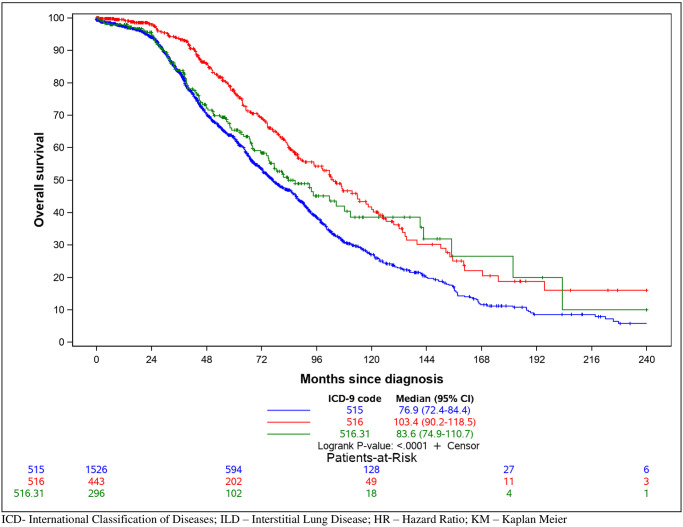

We then defined the incidence and prevalence of ILD in VISN6. Given our broad entry criteria for chart review, we applied broad and narrow case definitions to this analysis. A broad case definition was defined as any individual with an ILD diagnostic code. The narrow definition was defined as any individual with an ILD diagnostic code who had a HRCT scan or a bronchoscopic or surgical lung biopsy. The overall estimated prevalence in the verified ILD subjects (including 515 and 516) was 256 per 100,000 people (0.256%) with a mean incidence across the years of 70 per 100,000 person-years (0.07%). Prevalence and incidence rates stratified by VISN6 locations and year are in Table 3. Using the individual ICD-9 groupings, 515 had a prevalence of 158 (0.158%) and a mean incidence of 49 (0.049%), while the 516 group were 98 (0.098%) and 22 (0.022%), respectively. To determine the impact of the diagnosis on mortality, we used clinical data from this cohort over the course of their medical care within the VA. Fig 1 illustrates a Kaplan Meier curve comparing subjects with a 515, 516 (excluding 516.31), or 516.31. The median survival was 76.9 months for 515 codes, 103.4 months for 516 codes (excluding 516.31), and 83.6 months for 516.31. Notably, 515 and 516.31 had a lower survival rate than 516 subjects (excluding 516.31) (log-rank, p<0.001).

Table 3.

A. Prevalence and incidence of ILD at six VA health care centers among patients with ICD-9 515 or 516. B. Prevalence and incidence of ILD at six VA health care centers among patients with ICD-9 515 or 516 and HRCT, surgical lung biopsy, or transbronchial lung biopsy.

| A. | ||||||||||

| Prevalence (per 100,000 people) | Incidence (per 100,000 person-years) | |||||||||

| as of 12/31/15 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average | |

| Durham | 181 | 25 | 41 | 48 | 48 | 77 | 58 | 94 | 80 | 59 |

| Fayetteville | 106 | 18 | 32 | 39 | 38 | 46 | 38 | 45 | 29 | 36 |

| Asheville | 393 | 79 | 121 | 114 | 97 | 98 | 43 | 123 | 91 | 96 |

| Richmond | 240 | 40 | 101 | 73 | 81 | 81 | 56 | 135 | 70 | 80 |

| Salem | 395 | 59 | 96 | 64 | 77 | 88 | 65 | 98 | 80 | 78 |

| Salisbury | 138 | 20 | 147 | 99 | 111 | 117 | 78 | 158 | 108 | 105 |

| Average | 256 | 39 | 80 | 66 | 69 | 80 | 55 | 102 | 73 | 70 |

| B. | ||||||||||

| Prevalence (per 100,000 people) | Incidence (per 100,000 person-years) | |||||||||

| as of 12/31/15 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average | |

| Durham | 167 | 19 | 40 | 39 | 45 | 76 | 56 | 83 | 70 | 53 |

| Fayetteville | 97 | 18 | 30 | 32 | 31 | 41 | 37 | 37 | 29 | 32 |

| Asheville | 379 | 85 | 97 | 96 | 91 | 92 | 51 | 123 | 89 | 91 |

| Richmond | 254 | 33 | 99 | 73 | 71 | 86 | 54 | 126 | 64 | 76 |

| Salem | 365 | 57 | 90 | 59 | 59 | 69 | 62 | 97 | 74 | 71 |

| Salisbury | 106 | 13 | 103 | 79 | 77 | 90 | 64 | 147 | 93 | 83 |

| Average | 237 | 35 | 69 | 57 | 57 | 72 | 52 | 95 | 67 | 63 |

Incidence per 100,000 subjects was calculated as the number of subjects diagnosed with an ILD in each year divided by the number of unique subjects who visited one of the included VA centers in that calendar year. Incidence rates were then averaged across years. Prevalence per 100,000 subjects was calculated as the number of subjects diagnosed with an ILD before December 31st, 2015 and still alive at this date, divided by the number of unique subjects who visited one of the included VA centers in 2013–2015 and were alive as of December 31st, 2015 (as an estimate of the number of VA subjects in the system at these centers).

ILD–Interstitial Lung Disease

Fig 1. Kaplan Meier survival based on ICD-9 code.

Information obtained from electronic medical record review was used to define survival for all-cause mortality.

Discussion

The present study identifies and describes a cohort of ILD subjects within the Veteran’s Health Administration in the Mid-Atlantic Region. We embarked on this study to address if the veteran population is enriched for ILD. Our hypothesis was based on that fact that the veteran population exhibits risk factors (male sex, advanced age and active or prior smoking history) known to associate with increased ILD prevalence. In this study, we confirmed that ILDs are enriched in our veteran cohort, including IPF. Additionally, we noted a number of individuals (26% of cohort) coded with an ILD diagnostic code, but in whom there was no observed ILD following chart review.

Our study identified an estimated prevalence of 256 per 100,000 people and an average incidence across the study period of 70 per 100,000 person-years for ILD subjects using ICD-9 codes and EMR manual review. We analyzed this data using broad and narrow case definitions as some veterans do not receive all of their care in the VA, and to address concerns about the accuracy of the diagnosis. Even with this narrow case definition, the ILD incidence and prevalence was significantly higher than other literature on ILD epidemiology [8]. Previous ILD registries in the USA have estimated prevalence rates of 14.3–63 per 100,000 people and incidence rates of 7.4–17.3 per 100,000 person-years [9–11]. European ILD epidemiological studies have also estimated rates much lower than this study with incidence rates ranging from 0.76–34.34 per 100,000 person-years [12–17].

Our findings confirm the prevailing hypothesis that ILD is enriched within the VA. Though not proven in the present study this is likely due to increased risk factors for ILD in veterans. Whereas the prevalence of ever-smoking is less than 50% among the general population in the US, we found smoking rates to be more than 70%, consistent with enriched smoking rates in veterans [18]. Another potential explanation for the higher observed values is that our dataset evaluates a more generalized population than a specific registry. This is supported by recent studies using general population cohorts that demonstrated higher incident and prevalence rates than prior registry studies [19]. A limitation to our analysis is that the denominator we used to calculate incidence and prevalence was based on the number of patients who visited one of the included VA centers in a given time frame and did not include patients who are in the VA system but did not visit during that time period. Therefore, it is possible that we underestimated the total number of patients and therefore overestimated the incidence and prevalence rates. Our generous entry criteria (any individual with any ILD ICD-9 billing code during the defined study period) likely also identified more ILD subjects. Given that each of these underwent a manual EMR review, we are confident that this is not just a misclassification of individuals without ILD. Future studies will need to validate our observations in other VA regional networks and/or VA national databases.

We observed a significant population of subjects who had an ILD-associated billing code but no evidence of ILD following manual chart abstraction. This could suggest an inherent misunderstanding of the clinical criteria of ILD or coding based on an impression prior to obtaining imaging or other diagnostic studies. The extent of the miscoding was likely higher in our cohort due to our broad search criteria. This was purposely designed to be more inclusive in an attempt to capture as many individuals with ILD as possible. Despite this, our data are consistent with studies documenting inaccuracies in the use of billing codes for clinical research [20–22]. This issue was noted in recent a survey where more than half of the respondents with ILD had at least one clinical misdiagnosis [23]. Overall, our data highlights that caution should be used when defining ILD epidemiology solely based on cohorts identified by ICD codes without careful validation of their accuracy.

Interestingly, we observed a difference in survival between the 515 vs. 516 groups. Generally, IPF is considered the ILD with the highest mortality risk. As IPF falls under the 516 group (coded as 516.31), we expected that 516 mortality would be worse than those coded as 515. To address this, we also performed the analysis of the mortality of 516.31 separate from 516. The reason we observed worse mortality in the 515 group in our cohort is not clear. It is possible that IPF cases were misclassified as a 515 code. Similar to other epidemiological studies using ICD codes, we believe that the 515 code is sometimes used as the generic code for ILD, of which IPF is one of the most common diagnoses [11, 19, 24]. The Veteran population, based on demographics, has a pretest probability of IPF and thus even general 515 diagnostic codes may be capturing IPF. We observed a similar issue with use of the 516 codes, where the code for “IPF” (516.31) and the code for “other specified alveolar and parietoalveolar pneumonopathies” (516.8) exhibited very similar clinical characteristics, suggesting that the 516.8 code is likely a group that would be clinically diagnosed as IPF. Future studies will review specific clinical and radiographic criteria to evaluate miscoding between the 515 and 516 codes to understand the difference in mortality rates.

The comorbidities across the 515, 516, and other ILDs were similar except for higher rates of COPD in 515 codes. This is also reflected in the pulmonary function testing which showed a greater frequency of obstructed patterns in the 515 vs the other groups. Pulmonary function testing also noted a number of individuals with “isolated DLCO impairment” physiologic patterns. The high rates of obstructive and isolated DLCO impairment patterns could suggest a higher rate of co-existing emphysema, also known as combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema [25]. This could be explained by the higher rates of smoking generally seen in veteran cohorts [18]. We also noted higher rates of coronary disease in 516 ICD 9 codes, which have been associated with progressive fibrotic diseases [26, 27].

We also defined the frequency of diagnostic testing and therapeutic interventions for ILD within our cohort to determine how often veterans received appropriate interventions. The American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, and British Thoracic Society all provide best practice and guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of subjects with ILD [28, 29]. High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is critical for the initial diagnostic approach. Pulmonary function testing at diagnosis complements HRCT by providing a representation of severity. Furthermore, serial pulmonary function tests have prognostic value in ILD [30–33]. Despite relatively high performance of HRCT in this cohort, a significant proportion of the VA cohort did not receive PFTs, nor were these performed at later points as a measure to follow disease progression. A possible explanation is that many veterans receive healthcare principally through community-based providers and are only infrequently followed at the VA. Therefore, some of these studies may have been performed outside of the VA and were not captured in our database. Alternatively, it is possible that clinical care for ILD subjects in VA sites does not prioritize PFTs as an important clinical measure or that these patients have limited access to pulmonary providers with ILD expertise. Additionally, we noted low use of approved IPF therapies. A potential explanation is that the drugs were approved during the study period. Additionally, there was then a period of required central VA authorization of use and implementation at the individual VA sites in VISN6. Alternatively, this could reflect an unmet need in the VA, particularly at VISN6 sites which are not affiliated with academic medical centers where there is access to ILD specialists. In future work, we plan to explore differences by facility and available site resources.

Similar to other retrospective studies done on large datasets there are limitations to our analysis. First, our population only included United States military veterans from the Mid-Atlantic region, therefore this may not be generalizable to other VA sites. The veteran population is predominantly male, elderly, more-likely to be white, non-Hispanic, and economically dis-advantaged compared to the general population [34, 35]. Additionally, there may be a selection bias, as our cohort includes veterans who have opted to receive their medical care within the Veterans Health Administration. VHA users tend to be older, less economically advantaged, report more chronic medical conditions, and have higher rates of combat exposure than non-VHA users [36, 37]. We did not acquire data from outside the VHA health system for veterans that receive care through the community (i.e. non-VA community care). Prior studies of the veteran’s population has shown that two-thirds of veterans have access to non-VHA care through other government programs and that one-half of these veterans will receive care outside the VHA [38]. Veterans can also be sent to community providers through various VHA programs if there is a lack of specific ILD specialty providers or long wait times. Third, our study lacked age-matched controls to use a comparator group. Fourth, we relied on billing codes from a single encounter [39] to find our initial cohort, which, as noted above, can be inaccurate. The decision to use a single encounter was made to collect a population as comprehensive as possible with the limitation that this would likely increase our coding inaccuracies. Lastly, veteran deaths outside the VHA system are not generally recorded in the VHA data warehouse, thus potentially affecting our ability to accurately define mortality. Despite these limitations, we believe our results provide insight into the real-world epidemiology of interstitial lung disease and its impact on veterans’ health.

Conclusion

Here we report the epidemiology of a large distinct cohort of VHA patients with interstitial lung disease. Identifying patients by diagnostic codes followed by a detailed EMR review allow us, for the first time, to define the types and characteristics of ILD in a VHA population. Based on this analysis, veterans are at a substantially higher risk for developing ILDs than other non-VA cohorts. It highlights that ILD is a critical issue for veterans’ health, and requires increased attention and awareness for ILD within the VA.

Supporting information

(CSV)

(JPG)

(JPG)

(JPG)

(JPG)

Acknowledgments

JCB performed the initial subject identification and data extraction. RK assisted with data warehouse development, data cleaning, and data extraction. AB, RAP, RMT and AR performed chart abstraction and review for quality. LH performed the statistical analysis. DS and KW assisted with data interpretation. AB and RMT drafted the manuscript. RAP and RMT conceived of the overall project.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI). BIPI had no role in the design, analysis or interpretation of the results in this study. BIPI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as it relates to BIPI substances, as well as intellectual property considerations.

References

- 1.Marshall DC, Salciccioli JD, Shea BS, Akuthota P. Trends in mortality from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the European Union: an observational study of the WHO mortality database from 2001–2013. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1). Epub 2018/01/20. 10.1183/13993003.01603-2017 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collard HR, Ward AJ, Lanes S, Cortney Hayflinger D, Rosenberg DM, Hunsche E. Burden of illness in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Econ. 2012;15(5):829–35. Epub 2012/03/30. 10.3111/13696998.2012.680553 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naghavi M, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specifc mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. 2017. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, Reda D, Emanuele N, Reaven PD, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):129–39. Epub 2008/12/19. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(15):1503–16. Epub 2007/03/28. 10.1056/NEJMoa070829 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Group SMIftSR, Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, Auchus AP, Bryan RN, Chelune G, et al. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(6):553–61. Epub 2019/01/29. 10.1001/jama.2018.21442 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FY C. president’s budget request [fact sheet]. 2017.

- 8.Duchemann B, Annesi-Maesano I, Jacobe de Naurois C, Sanyal S, Brillet PY, Brauner M, et al. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial lung diseases in a multi-ethnic county of Greater Paris. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2). Epub 2017/08/05. 10.1183/13993003.02419-2016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994. 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921471 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez Perez ER, Daniels CE, Schroeder DR, St Sauver J, Hartman TE, Bartholmai BJ, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a population-based study. Chest. 2010;137(1):129–37. 10.1378/chest.09-1002 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2006;174(7):810–6. 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomeer M, Demedts M, Vandeurzen K. Registration of interstitial lung diseases by 20 centres of respiratory medicine in flanders. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2001. 10.1179/acb.2001.026 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roelandt M, Demedts M, Callebaut W, Coolen D, Slabbynck H, Bockaert J, et al. Epidemiology of interstitial lung disease (ILD) in flanders: registration by pneumologists in 1992–1994. Working group on ILD, VRGT. Vereniging voor Respiratoire Gezondheidszorg en Tuberculosebestrijding. Acta Clin Belg. 1995;50(5):260–8. Epub 1995/01/01. 10.1080/17843286.1995.11718459 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xaubet A, Ancochea J, Morell F, Rodriguez-Arias JM, Villena V, Blanquer R, et al. Report on the incidence of interstitial lung diseases in Spain. Sarcoidosis Vasculitis and Diffuse Lung Diseases. 2004. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Campos JL, Rodríguez-Becerra E. Incidence of interstitial lung diseases in the south of Spain 1998–2000: The RENIA study. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2004. 10.1023/b:ejep.0000017660.18541.83 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karakatsani A, Papakosta D, Rapti A, Antoniou KM, Dimadi M, Markopoulou A, et al. Epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases in Greece. Respiratory Medicine. 2009. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornum JB, Christensen S, Grijota M, Pedersen L, Wogelius P, Beiderbeck A, et al. The incidence of interstitial lung disease 1995–2005: A Danish nationwide population-based study. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2008. 10.1186/1471-2466-8-24 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamlett-Berry K, Davison J, Kivlahan DR, Matthews MH, Hendrickson JE, Almenoff PL. Evidence-based national initiatives to address tobacco use as a public health priority in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2009;174(1):29–34. Epub 2009/02/17. 10.7205/milmed-d-00-3108 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS, Maroni B, Li Q, Lee YC, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: Incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001–11. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2014. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70101-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh H, Meyer AND, Thomas EJ. The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiskopf NG, Weng C. Methods and dimensions of electronic health record data quality assessment: enabling reuse for clinical research. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013;20:144–51. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan KS, Fowles JB, Weiner JP. Electronic health records and the reliability and validity of quality measures: a review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review. 2010;67:503–27. 10.1177/1077558709359007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosgrove GP, Bianchi P, Danese S, Lederer DJ. Barriers to timely diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in the real world: The INTENSITY survey. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2018. 10.1186/s12890-017-0560-x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mannino DM, Etzel RA, Parrish RG. Pulmonary fibrosis deaths in the United States, 1979–1991. An analysis of multiple-cause mortality data. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1996;153(5):1548–52. 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630600 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryerson CJ, Hartman T, Elicker BM, Ley B, Lee JS, Abbritti M, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2013;144(1):234–40. Epub 2013/02/02. 10.1378/chest.12-2403 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponnuswamy A, Manikandan R, Sabetpour A, Keeping IM, Finnerty JP. Association between ischaemic heart disease and interstitial lung disease: a case-control study. Respir Med. 2009;103(4):503–7. Epub 2009/02/07. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.01.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kizer JR, Zisman DA, Blumenthal NP, Kotloff RM, Kimmel SE, Strieter RM, et al. Association between pulmonary fibrosis and coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(5):551–6. Epub 2004/03/10. 10.1001/archinte.164.5.551 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013. 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Interstitial lung disease guideline: The British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society, (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Collard HR, King TE, Bartelson BB, Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Brown KK. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2003. 10.1164/rccm.200211-1311OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flaherty KR, Mumford JA, Murray S, Kazerooni EA, Gross BH, Colby TV, et al. Prognostic implications of physiologic and radiographic changes in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2003. 10.1164/rccm.200209-1112OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jegal Y, Dong SK, Tae SS, Lim CM, Sang DL, Koh Y, et al. Physiology is a stronger predictor of survival than pathology in fibrotic interstitial pneumonia. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005. 10.1164/rccm.200403-331OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King TE, Safrin S, Starko KM, Brown KK, Noble PW, Raghu G, et al. Analyses of efficacy end points in a controlled trial of interferon-γ1b for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2005. 10.1378/chest.127.1.171 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein R, Stockford D. The Changing Veteran Population 1990–2020. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Data on the Socioeconomic Status of Veterans and on VA Program Usage. Office of the Actuary, Veterans Health Administration. 2001, (2013).

- 36.Agha Z, Lofgren RP, Vanruiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at veterans affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000. 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, Skinner K, Lee A, Rogers W, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the department of veterans affairs: Results from the health study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998. 10.1001/archinte.158.6.626 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen Y, Hendricks A, Zhang S, Kazis LE. VHA enrollees’ health care coverage and use of care. Medical care research and review: MCRR. 2003;60:253–67. 10.1177/1077558703060002007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Malley KJ, Cook KF, Price MD, Wildes KR, Hurdle JF, Ashton CM. Measuring diagnoses: ICD code accuracy. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 Pt 2):1620–39. Epub 2005/09/24. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00444.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]