Rapid vaccine-induced population immunity is a key global strategy to control COVID-19. Vaccination programmes must maximise early impact, particularly with accelerated spread of new variants.1 Most vaccine platforms use a two-dose prime-boost approach to generate an immune response against the virus S1 spike protein, the titres of which correlate with functional virus neutralisation and increase with boosting.2, 3 To enable larger numbers of people to receive the first dose, delayed administration of the second dose has been advocated and implemented by some.1 The impact of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection on the need for boosting is not known.

We reasoned that previous infection could be analogous to immune priming. As such, a first prime vaccine dose would effectively act as boost, so a second dose might not be needed. To test this, we undertook a nested case-control analysis of 51 participants of COVIDsortium,4, 5 an ongoing longitudinal observational study of health-care workers (HCWs) in London who underwent weekly PCR and quantitative serology testing from the day of the first UK lockdown on March 23, 2020, and for 16 weeks onwards. 24 of 51 HCWs had a previous laboratory-confirmed mild or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, as confirmed by positive detection of antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 N ECLIA, Roche Diagnostics, Burgess Hill, UK) or the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 S1 subunit of the spike protein (anti-S; Elecsys anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike ECLIA, Roche Diagnostics), whereas 27 HCWs remained seronegative. A median of 12·5 sampling timepoints per participant permitted the identification of peak antibody titres in seropositive individuals while avoiding false negatives.

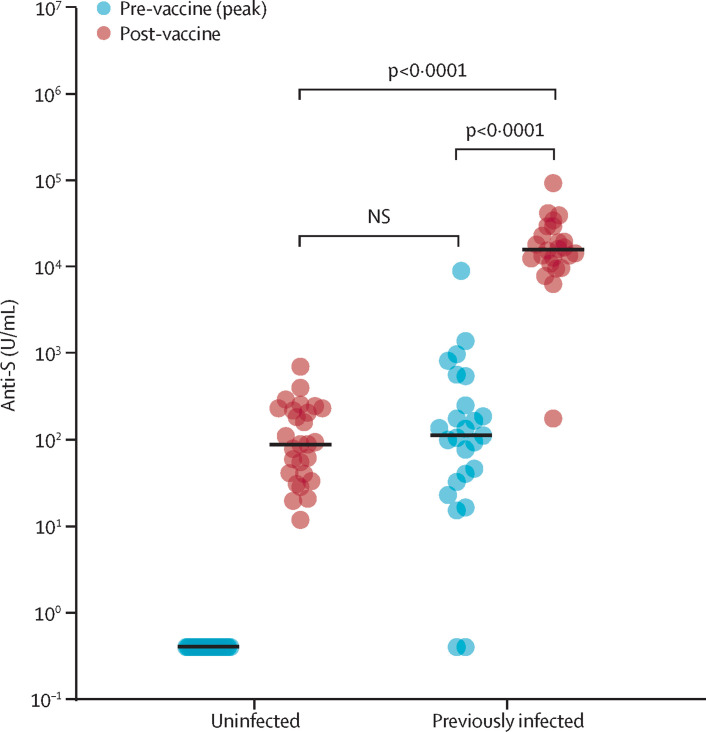

All participants received their first dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech, Mainz, Germany)2, 3 and were tested 19–29 days later (median 22 days, IQR 2). Among previously uninfected, seronegative individuals, anti-S titres after one vaccine dose were comparable to peak anti-S titres in individuals with a previous natural infection who had not yet been vaccinated. Among those with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccination increased anti-S titres more than 140-fold from peak pre-vaccine levels (figure ). This increase appears to be at least one order of magnitude greater than reported after a conventional prime-boost vaccine strategy in previously uninfected individuals.3

Figure.

Serological response to one dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in individuals with and without laboratory-confirmed previous SARS-CoV-2 infection

SARS-CoV-2 anti-S antibody titres in individuals with no previous infection are similar to titres in individuals who have had a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Anti-S titres in those with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection are more than 140-fold greater than at time of peak infection. Statistical analysis was by unpaired two-tailed t test. U=unit. NS=non-significant.

These serological data suggest that for individuals receiving the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine, a potential approach is to include serology testing at or before the time of first vaccination to prioritise use of booster doses for individuals with no previous infection. This could potentially accelerate vaccine rollout. With increasing variants (UK, South Africa, Brazil), wider coverage without compromising vaccine-induced immunity could help reduce variant emergence. Furthermore, reactogenicity after unnecessary boost risks an avoidable and unwelcome increase in vaccine hesitancy.

Whether enhanced vaccine-induced antibody responses among previously seropositive individuals will show differential longevity compared to boosted vaccines remains to be seen. In the meantime, our findings provide a rationale for serology-based vaccine dosing to maximise coverage and impact.

Acknowledgments

CM and ADO contributed equally. AS and JCM contributed equally. All authors' contributions are listed in the appendix. Funding details for this Correspondence are provided in the appendix. DMA and RJB have consulted as members of Global T cell Expert Consortium, Oxford Immunotec, UK. All other authors declare no competing interests. The corresponding author had full access to all data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation Optimising the COVID-19 vaccination programme for maximum short-term impact. Jan 26, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prioritising-the-first-covid-19-vaccine-dose-jcvi-statement/optimising-the-covid-19-vaccination-programme-for-maximum-short-term-impact

- 2.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Eng J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh EE, Frenck RW, Falsey AR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based COVID-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treibel TA, Manisty C, Burton M, et al. COVID-19: PCR screening of asymptomatic health-care workers at London hospital. Lancet. 2020;395:1608–1610. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31100-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds CJ, Swadling L, Gibbons JM, et al. Discordant neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in asymptomatic and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abf3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.