Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected all facets of life and continues to cripple nations. COVID-19 has taken the lives of more than 2.1 million people worldwide, with a global mortality rate of 2.2%. Current COVID-19 treatment options include supportive respiratory care, parenteral corticosteroids, and remdesivir. Although COVID-19 is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality in patients with comorbidities, the vulnerability, clinical course, optimal management, and prognosis of COVID-19 infection in patients with organ transplants has not been well described in the literature. The treatment of COVID-19 differs based on the organ(s) transplanted. Preliminary data suggested that liver transplant patients with COVID-19 did not have higher mortality rates than untransplanted COVID-19 patients. Table 1 depicts a compiled list of current published data on COVID-19 liver transplant patients. Most of these studies included both recent and old liver transplant patients. No distinction was made for early liver transplant patients who contract COVID-19 within their posttransplant hospitalization course. This potential differentiation needs to be further explored. Here, we report 2 patients who underwent liver transplantation who acquired COVID-19 during their posttransplant recovery period in the hospital.

Case Descriptions

Two patients who underwent liver transplant and contracted COVID-19 in the early posttransplant period and were treated with hydroxychloroquine, methylprednisolone, tocilizumab, and convalescent plasma. This article includes a description of their hospital course, including treatment and recovery.

Conclusion

The management of post-liver transplant patients with COVID-19 infection is complicated. Strict exposure precaution practice after organ transplantation is highly recommended. Widespread vaccination will help with prevention, but there will continue to be patients who contract COVID-19. Therefore, continued research into appropriate treatments is still relevant and critical. A temporary dose reduction of immunosuppression and continued administration of low-dose methylprednisolone, remdesivir, monoclonal antibodies, and convalescent plasma might be helpful in the management and recovery of severe COVID-19 pneumonia in post-liver transplant patients. Future studies and experiences from posttransplant patients are warranted to better delineate the clinical features and optimal management of COVID-19 infection in liver transplant recipients.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected all facets of life and continues to cripple nations. COVID-19 has taken the lives of more than 2.1 million people worldwide [1], with a global mortality rate of 2.2% [1]. Current COVID-19 treatment options include supportive respiratory care, parenteral corticosteroids, and remdesivir. The RECOVERY study by the National Health Service in England showed 22.9% of participants in the dexamethasone arm vs 25.7% in the standard of care arm died within 28 days of study randomization [2,3]. Remdesivir was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in October 2020 [3]. The Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial is a National Institutes of Health-sponsored, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that showed remdesivir significantly reduced the time to recovery compared with placebo.

As of 2021, the National Institutes of Health recommend against the use of chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, HIV protease inhibitors, and anti-interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor monoclonal antibodies, such as sarilumab, bamlanivimab, and tocilizumab [3]. This is in contrast to early recommendations based on the limited information available at the time that the patients were transplanted [4]. COVID-19 vaccinations are currently being processed and administered worldwide, with encouraging early data for development of immunity.

Although COVID-19 is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality in patients with comorbidities, the vulnerability, clinical course, optimal management, and prognosis of COVID-19 infection in patients with organ transplants has not been well described in the literature [5,6]. The treatment of COVID-19 differs based on the organ(s) transplanted [7]. Preliminary data suggested that liver transplant patients with COVID-19 did not have higher mortality rates than untransplanted COVID-19 patients [8]. Table 1 depicts a compiled list of current published data on COVID-19 liver transplant patients [5,8,[9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. Most of these studies included both recent and old liver transplant patients. No distinction was made for early liver transplant patients who contract COVID-19 within their posttransplant hospitalization course. This potential differentiation needs to be further explored [16]. Here, we report 2 patients who underwent liver transplantation who acquired COVID-19 during their posttransplant recovery period in the hospital.

Table 1.

Published Case Reports and Cohort Studies of COVID-19 Patients Over the Last Several Months

| Author | Liver Transplant With COVID-19 | Recent Transplant (<2 y) | Died | Mortality Rate | Old Transplant (>2 y) | Died | Mortality Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhoori S. [8] | 6 | 3 | 3 | 100% | 3 | 0 | 0% |

| Colmenero J. [9] | 111 | - | - | - | 111 | 20 | 18% |

| Kolonko A. [10] | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Niknam R. [11] | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Becchetti C. [12] | 57 | - | - | - | 57 | 7 | 12% |

| Webb GJ. [13] | 39 | - | - | - | 39 | 9 | 23% |

| Kates OS. [5] | 73 | - | - | - | 73 | 15 | 21% |

| Waisberg DR. [14] | 5 | 5 | 2 | 40% | - | - | - |

| Zhong Z. [15] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0% | - | - | - |

| Total | 295 | 9 | 5 | 55% | 286 | 52 | 18% |

Recent transplant cutoff was defined as within the last 2 years. Patients with old liver transplant were those who had received their transplant over 2 years ago.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Case Descriptions

Case 1

The patient was a 65-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C–related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Her calculated Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 12 with a MELD exception of 28 owing to porto-pulmonary hypertension. The patient also had a history of rheumatoid arthritis, uterine fibroids, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, candida esophagitis, herpes simplex keratitis, hepatic encephalopathy, moderate to severe porto-pulmonary hypertension, and psoriatic arthritis.

She underwent an orthotopic liver transplant and umbilical hernia repair on March 20, 2020 using the piggyback liver transplantation technique, with an estimated blood loss of 2000 mL. The native liver was a cirrhotic. The brain-dead donor was a 35-year-old woman who died of anoxia from an opioid overdose. Donor COVID-19 Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was undetectable. The donor was also hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody positive. The warm and cold ischemia times were 35 minutes and 7 hours, 32 minutes, respectively.

Postoperatively the patient went to the intensive care unit (ICU) and was extubated on postoperative day (POD) 1. She was treated with a standard immunosuppressive regimen of 2 mg of tacrolimus every 12 hours and 200 mg of methylprednisolone once, as well as posttransplant prophylaxis with 160 mg of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim once every other day, 450 mg of valganciclovir every day, and 500,000 units of nystatin as needed. Fibrinogen level was 192, White Blood Cell Count (WBC) 4.5, and tacrolimus level was 1.8. She was transferred to the floor and started on hepatitis C treatment with glecaprevir and pibrentasvir on POD 7.

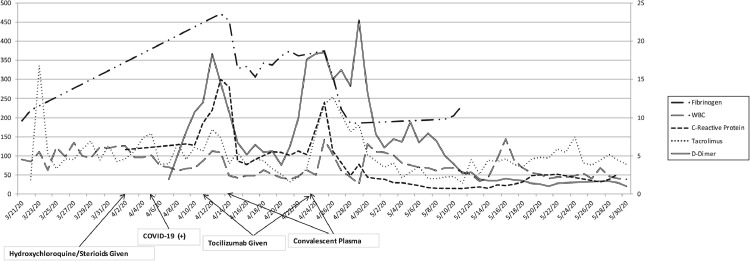

Our patient's roommate developed respiratory symptoms after their discharge. The roommate was diagnosed with COVID-19 infection, requiring ICU admission and intubation. On POD 13 our patient was started on prophylactic 200 mg of hydroxychloroquine every 12 hours and subsequently tested positive for COVID-19 on POD 16. D-dimer level was 1.89, C-reactive protein (CRP) was 6.5 and WBC 4.5. On POD 23, she developed progressive respiratory distress with oxygen desaturation (O2 saturation of 70%). She was transferred to the ICU and intubated. Oral prednisone was changed to 5 mg of methylprednisolone daily on POD 24. Inflammatory markers including procalcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, CRP, fibrinogen, lactate, and D-dimer were monitored daily in addition to tacrolimus levels and liver enzymes (Fig 1 ).

Fig 1.

Inflammatory markers over Case 1 patient's hospital course marked with timing of COVID-19 infection and medical treatments. Trend of fibrinogen, WBC, C-reactive protein, tacrolimus, and D-dimer levels throughout patient's course. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; WBC, whilte blood cell count.

On POD 23 the patient received 400 mg of tocilizumab and 1 unit of convalescent plasma on POD 25 owing to spikes in inflammatory markers: D-dimer had increased to 18.34, fibrinogen increased to 472, CRP increased to 15, but WBC was unchanged at 5.4 (Fig 1). Inflammatory markers subsequently decreased after tocilizumab and convalescent plasma: D-dimer had decreased to 5.17, fibrinogen decreased to 333, CRP decreased to 3.9, and WBC was 2.4 (Fig 1). Repeat severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA testing was positive on POD 31. Inflammatory markers were also increased on POD 36: D-dimer had increased to 18.51, fibrinogen increased to 374, CRP increased to 12, but WBC had increased to 7.1 (Fig 1). The patient received another dose of 400 mg of tocilizumab and 1 unit of convalescent plasma.

Tracheostomy was performed on POD 41 because the patient was unable to wean off the ventilator. Inflammatory markers continued to downtrend: D-dimer had decreased to 5, fibrinogen decreased to 195, CRP decreased to 0.78, and WBC was 3.4 (Fig 1). She was retested for COVID-19 PCR and was found to be negative on POD 56. On post–COVID-19 exposure day 55 she tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody. She improved slowly, was subsequently decannulated, and discharged home on POD 88.

Case 2

The patient was a 58-year-old woman with a history of decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis and massive ascites who was admitted for liver transplantation on March 24, 2020. The liver allograft was procured from a 35-year-old man who had sustained anoxic brain injury after an opioid overdose. Donor COVID-19 PCR was undetectable. The donor was HCV antibody positive, HCV Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing negative. The estimated blood loss was 1200 mL. The cold and warm ischemia times were 5 hours and 47 minutes and 35 minutes, respectively.

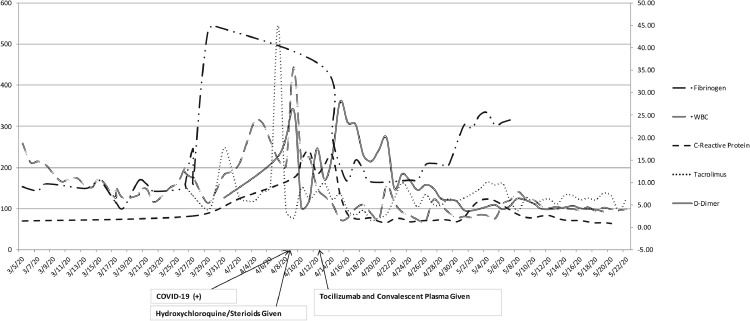

The patient was admitted to the ICU postoperatively and started on standard immunosuppressive therapy with 2 mg of tacrolimus every 12 hours, 500 mg of mycophenolate every 12 hours, and 200 mg of methylprednisolone once, as well as posttransplant prophylaxis with 160 mg of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim once every other day, 450 mg of valganciclovir every day, and 500,000 unit nystatin as needed. Fibrinogen level was 149, WBC 13.4, and tacrolimus level was 9.2. She was extubated on POD 1 and transferred to the floor on POD 6. Inflammatory markers including procalcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, CRP, fibrinogen, lactate, and D-dimer were monitored daily in addition to tacrolimus levels and liver enzymes (Fig 2 ).

Fig 2.

Inflammatory markers over Case 2 patient's hospital course marked with timing of COVID-19 infection and medical treatments. Trend of fibrinogen, WBC, C-reactive protein, tacrolimus, and D-dimer levels throughout patient's course. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; WBC, white blood cell count.

The patient was retested for COVID-19 on POD 16 before rehabilitation placement and was found to be positive, subsequently started on 200 mg of hydroxychloroquine every 12 hours. D-dimer level was 26.23, CRP was 11, fibrinogen 441, and WBC 35.7 (Fig 2). She developed progressive respiratory failure on POD 17, requiring intubation and transfer to the ICU. Oral prednisone was changed to 75 mg of methylprednisolone daily on POD 17 and gradually tapered to 40 mg on POD 20, 20 mg on POD 21, 5 mg on POD 22 and continued at this dose. The patient received 400 mg tocilizumab on POD 20 and convalescent plasma on POD 21. Inflammatory markers subsequently decreased after tocilizumab and convalescent plasma: D-dimer had decreased to 14.66, fibrinogen decreased to 165, CRP decreased to 2.10, and WBC was 3.1 (Fig 2).

Pancytopenia resulted and antibiotic coverage broadened to meropenem and micafungin. She required prone positioning for persistent hypoxemia several times. She had a trial of extubation that ultimately failed on POD 30 and was re-intubated. Repeat SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing was positive on POD 33. On POD 38, the patient underwent a tracheostomy. SARS-CoV2-RNA testing was negative on POD 60. The patient was transferred to the inpatient physical rehabilitation unit on POD 64.

Discussion

Here we report our experiences managing 2 early post-liver transplant patients who acquired COVID-19 during their hospital course. The outcomes of COVID-19 infection within 2 weeks of liver transplantation are currently unknown, but based on several case studies there is an 18% to 55% mortality rate in liver transplant patients who contract COVID-19 (Table 1). In all solid organ transplant patients, Kates et al found a 28-day mortality rate of 20.5% among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [5].

As of today, temporary dosage reduction or withdrawal of immunosuppressive agents in the early stage of infection with COVID-19 is recommended as a strategy to avoid serious complications of COVID-19 [17]. It is unclear how to properly dose corticosteroids in COVID-19–infected transplant recipients. High-dose corticosteroids have the potential to help protect against allograft rejection while decreasing the cytokine storm seen in cases of severe COVID-19 infection [2].

Our experience suggests the beneficial effects of early and aggressive dexamethasone and antiviral drug treatment. IL-6 inhibitors and convalescent plasma were given to our patients to treat cytokine storm. Inflammatory markers decreased dramatically in our patients after the administration of convalescent plasma and tocilizumab (Fig 1 and 2). However, a recent study did not demonstrate the efficacy of tocilizumab [3,18]. Therefore, we no longer use IL-6 antagonists for treatment of transplant patients with COVID-19.

Bamlanivimab is a monoclonal antibody that is specifically directed against the spike protein of COVID-19, designed to block the virus’ attachment and entry into human cells [19]. It appears to be safe when it is used to treat outpatients with moderate COVID-19 infection [19]. Conversely, this was a preliminary paper based on the BLAZE-1 trial, and when comparing the clinical outcomes the results showed minimal differences between the drug and control. Based on the demonstrated safety and potential benefit, our hospital has been using bamlanivimab with our severe COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions

The management of post-liver transplant patients with COVID-19 infection is complicated. Strict exposure precaution practice after organ transplantation is highly recommended. Widespread vaccination will help with prevention, but there will continue to be patients who contract COVID-19. Therefore, continued research into appropriate treatments is still relevant and critical. A temporary dose reduction of immunosuppression and continued administration of low-dose methylprednisolone, remdesivir, monoclonal antibodies, and convalescent plasma might be helpful in the management and recovery of severe COVID-19 pneumonia in post-liver transplant patients. Future studies and experiences from posttransplant patients are warranted to better delineate the clinical features and optimal management of COVID-19 infection in liver transplant recipients.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO; 2020. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. <covid19.who.int/> accessed January 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. What's New, www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/. 2021 accessed January 13, 2021.

- 4.Dashti-Khavidaki S, Mohammadi K, Khalili H, Abdollahi A. Pharmacotherapeutic considerations in solid organ transplant patients with COVID-19. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21:1813–1819. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2020.1790526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kates O, Haydel B, Florman S, Rana M, Chaudhry Z, Ramesh M, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in solid organ transplant: a multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molnar MZ, Bhalla A, Azhar A, Tsujita M, Talwar M, Balaraman V, et al. Outcomes of critically ill solid organ transplant patients with COVID-19 in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:3061–3071. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DheIr H, Sipachi S, Yaylaci S, et al. Clinical course of COVID-19 disease in immunosuppressed renal transplant patients [e-pub ahead of print]. Turk J Med Sci. doi: 10.3906/sag-2007-260, accessed January 13, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Bhoori S, Elisa Rossi R, Citterio D, Mazzaferro V. COVID-19 in long-term liver transplant patients: preliminary experience from an Italian transplant centre in Lombardy. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:532–533. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30116-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colmenero J, Rodriguz-Peralvarez M, Salcedo M, Tome S, De la Rosa G, Antonio Pons J, et al. Epidemiological pattern, incidence and outcomes of COVID-19 in liver transplant patients. J Hepatol. 2021;74:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolonko A, Dudzicz S, Wiecek A, Król R. COVID-19 infection in solid organ transplant recipients: a single-center experience with patients immediately after transplantation [e-pub ahead of print]. Transpl Infect Dis. doi: 10.1111/tid.13381, accessed January 13, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Niknam R, Ali Malek-Hosseini S, Saeid Hashemieh S, et al. COVID-19 in liver transplant patients: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Int Med Case Rep J. 2020;13:317–321. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S265910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becchetti C, Fabrizio Zambelli M, Pasulo L, Donato F, Invernizzi F, Detry O, et al. COVID-19 in an international European liver transplant recipient cohort. Gut. 2020;69:1832–1840. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb G, Moon A, Barnes E, Barritt S, Marjot T. Determining risk factors for mortality in liver transplant patients with COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:643–644. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30125-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waisberg DR, Abdala E, Nacif LS, et al. COVID-19 in the early postoperative period of liver transplantation: is the outcome really so positive? [e-pub ahead of print]. Liver Transplant. doi:10.1002/lt.25933, accessed January 13, 2021.

- 15.Zhong Z, Zhang Q, Xia H, Wang A, Linag W, Zhou W, et al. Clinical characteristics and immunosuppressant management of coronavirus disease 2019 in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1916–1921. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NasrAllah MM, Osman NA, Elalfy M, Malvezzi P, Rostaing L. Transplantation in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic: how should transplant patients and programs be handled? Rev Med Virol. 2021;31:1–9. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maggiore U, Abramowicz D, Crespo M, Mariat C, Mjoen G, Peruzzi L, et al. How should I manage immunosuppression in a kidney transplant patient with COVID-19? An ERA-EDTA DESCARTES expert opinion. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:899–904. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trujillo H, Caravaca-Fontan F, Sevillano A, Gutierrez E, Fernandez-Ruiz M, Lopez-Medrano F, et al. Tocilizumab use in kidney transplant patients with COVID-19. Clin Transplant. 2020;34:e14072. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.