Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant changes and restrictions to neonatal care. The aim of this study was to explore the impact of these changes on neonatal nurses globally.

Methods

We conducted a thematic analysis on written reflections by neonatal nurses worldwide, exploring their experiences of COVID-19. Twenty-two reflections were analysed from eleven countries.

Results

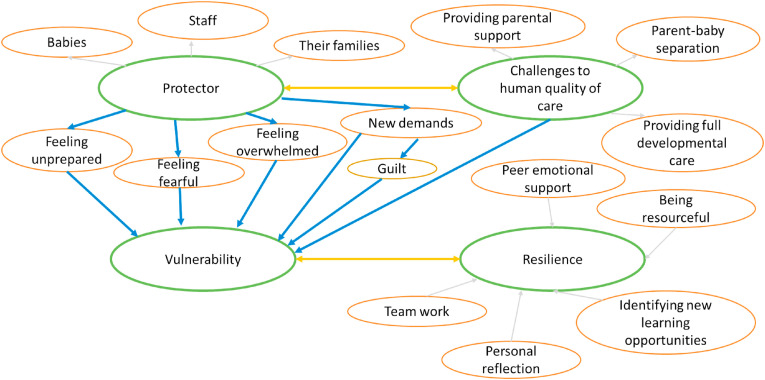

Thematic analysis revealed 4 main themes relating to the nurses’ role: 1) protector 2) challenges to human quality of care 3) vulnerability and 4) resilience. The measures taken as protector were described as compromising the human qualities of care fundamental to their role. This tension, together with other new challenges, heightened feelings of vulnerability. Concurrently, nurses identified role resilience, including resourcefulness and peer support, which allowed them to navigate the global pandemic.

Conclusion

By identifying global challenges and strategies to overcome these, neonatal nurses may be better equipped as the pandemic continues. The reflections underscore the importance of family integrated care and the tension created when it is compromised.

Keywords: Neonatal, COVID-19, Neonatal nurses, Personal reflections, Pandemic, Thematic analysis, Resilience, Family integrated care, Peer support

Introduction

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has led to the refocusing of health services across the world to deliver a high-volume adult intensive care service. Policies were put in place to limit climbing numbers of infections across healthcare settings, including strategies to protect sick newborns and the health care staff looking after them. There was concern that pregnant women were more vulnerable to infection (Favre et al., 2020) and the risk to their new-born babies was uncertain (Knight et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). The restrictions put in place to specifically limit the spread of COVID-19 in neonatal units varied internationally (Tscherning et al., 2020) and between hospitals, according to the adaptation of guidelines by individual Trusts.

Of particular significance in neonatal care, have been the restrictions imposed on parental visitation. Changes in policies to parental access in neonatal units has restricted the ability of parents to spend unlimited time with their baby, with some units limiting access to only one hour per day. The need for parents to self-isolate or shield has impacted visitation even further. In some cases these restrictions meant that emotionally challenging practices, such as communicating bad news to families, occured via video calls rather than face-to-face with one to one support, in a quiet room. Of further concern in neonatal settings is the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), which prohibits skin to skin contact, negatively impacting parent-baby bonding (Naranje et al., 2020).

A main role of the neonatal nurse is to promote and facilitate family engagement in their infants' care. Parental disruptions from changed policies, therefore profoundly impacted the working lives of neonatal nurses. The global commitment to delivering Family Integrated Care (Skene et al., 2019) has been disturbed with social distancing measures, which has undermined the nurse's ability to provide peer support in coping with this situation. The use of PPE interrupts non-verbal communication among professionals. Closed staff rooms and the implementation of staggered breaks results in less opportunity for informal debrief and connectivity. Staff with transferable skills were pulled from the neonatal unit to paediatric and adult services, worsening morale and the well-described existing staff shortages (Gallagher et al., 2020; National Neonatal Audit Programme, 2019).

The psychological impact on health care professionals caring for patients with COVID-19 includes high rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and for nurses in particular, an increased risk of contracting the infection due to the close and enduring contact with critically ill COVID-19 positive patients (Pappa et al., 2020). A growing body of research has examined the experiences of nurses caring for COVID-19 patients in adult intensive care (Fernandez et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020); however, the impact on nurses working in the neonatal environment where both babies and parents are cared for remains unknown.

The aim of this study was to explore the global experiences of neonatal nurses during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and identify strategies used to address challenges they continue to face.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were recruited using a purposive sampling approach and were comprised of neonatal nurses across the world who have worked during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurses were recruited through passive recruitment calls on social media platforms and through advertisements placed in the Journal of Neonatal Nursing. Nurses were invited to volunteer to participate in the study by contacting the research team (Gelinas et al., 2017). A broad range of strategically targeted online and social media platforms, as well as email contacts were targeted in order to obtain global representation of neonatal nurses’ experiences. Targeting profession-specific platforms helped overcome the potential problem of low recruitment levels in social media research (Arigo et al., 2018).

Data collection

Qualitative data were collected in the form of written reflections that were submitted to a reflective writing series in the Journal of Neonatal Nursing. Nurses were asked to write an unrestricted open reflection (with minimal influence from the researcher) about their experiences when working during the COVID-19 pandemic. The following written instructions were given: “We would like to explore how our neonatal nursing community is preparing for and dealing with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic ….We want to hear the thoughts and experiences of neonatal nursing colleagues all around the world, to show how we are working together to help babies and families that we care for.” Reflections were collected from April 2020 to October 2020, capturing experiences that occurred during the first wave of the pandemic.

Data analysis

Individual reflections were uploaded in to NVivo 2012, a qualitative data management software package designed to assist in the analysis of qualitative data. Reflexive thematic analysis was carried out, through which patterns of shared meaning were developed and pulled together by a central interpretive story (Braun and Clarke, 2019). An inductive, data-driven approach was taken to explore the experiences of neonatal nurses from their own perspectives. The data were systematically coded into numerous recurrent sematic codes and then were developed into broader semantic themes. These were then organized into a hierarchy of broad and basic themes. Two researchers (CS and KG) reviewed the codes and themes to increase the validity of the analysis and reduce any potential for lone researcher bias.

Ethical considerations

Recruiting participants through social media raises important ethical issues (Gelinas et al., 2017). However, because i) participants weren't actively/individually recruited, ii) participants were accessed by fellow neonatal colleagues, and iii) the professional group of neonatal nurses are not a vulnerable group, the ethical concerns for participants were minimal (Gelinas et al., 2017).

All participants have consented to have their reflections published on the Neonatal Nursing Association (NNA) website and within academic journals for research purposes. All names have been removed from direct quotes in the analysis.

Results

A total of 24 neonatal nurses working in a variety of clinical, educational and research roles took part in the study from 11 countries, including: England, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Sweden, Spain, Portugal, Malta, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil and the USA. On two occasions the nurses gave joint reflections resulting in a total of 22 reflections. Of the nurses, 23 were female and 1 was male.

Thematic analysis findings

The thematic analysis revealed four organisational themes from the nurses’ reflections: 1) protector 2) challenges to the human quality of care 3) nurse vulnerability and 4) nurse resilience. Fig. 1 below shows the relationships between the organisational themes and lower level basic themes.

-

1.Protector

-

a.Protecting the babies

-

a.

Fig. 1.

Overview of themes and their relationships.

The nurses were clear in their priority to protect the babies they cared for, referring to them as vulnerable and fragile. There was a sense of fear and anxiety coupled with this goal to protect the babies:

Extract 1: “I fear what this might mean for our most vulnerable patients - the patients born so early and so frail, with no immune system to speak of and already fighting the greatest battle of their lives.” (United States)

-

b.

Protecting staff

The nurses expressed a need to protect one another, as well as the babies. They identified this priority as secondary to the protection of babies, as can be seen in the following extract:

Extract 2: “Guidelines, policies and pathways were introduced to ensure the care of a so called “red patient” (a baby/family which is either suspected or confirmed to have Covid19) was to the highest standard, whilst protecting ourselves.” (England)

Tension was expressed when the protection of nurses was compromised by parents and the public not maintaining social distancing (Sweden), and conversely, when protecting nurses was seen to compromise the care of families (Northern Ireland).

-

c.

Protecting nurses' families

The nurses were concerned about protecting their own families, including those who were particularly vulnerable. This concern was positioned after the protection of babies, as well as staff:

Extract 3: “At the beginning of the pandemic we struggled with anxiety over the unknown and how we can protect patients, us and our own families.” (England)

In order to protect their families, the nurses reported plans to isolate from their families if the need arose. This separation period, reported by a few, was clearly very challenging for those nurses.

Extract 4: “I left home to quarantine for a fortnight. No byes, no kisses, no hugs. Worried, isolated, afraid, unable to explain to my kids. A fortnight of quarantine was an awful experience. We would video call multiple times a day only to make me feel miserable afterwards.” (Malta)

-

2.

Challenges to the human quality of care

Whilst protection was clearly a priority, some of the measures taken (social distancing from parents and the use of PPE), were felt to compromise the human quality of care provided to both babies and parents.

-

a.

Providing parental support

Measures taken to stop the spread of the virus were seen as compromising the care that was provided to parents. PPE shields against the COVID-19 virus, but was also considered by nurses to limit the way reassurance and care was communicated to parents.

Extract 6: “When PPE stands for Preventing Portrayal of Emotions: the physical barrier of visors, goggles and masks create an obstruction for parents of preterm infants to see our emotions, empathy and feelings. It is our ability to interpret, display and respond to emotions that cements our nursing practice. Our caring hands can no longer … deliver a gentle touch to inform those that we are here and we understand. Our non-verbal communication has been diminished … and reduce touch to convey emotion or connection.” (Northern Ireland)

-

b.

Parent-baby separation

Nurses discussed concerns over the distress that parents experienced as a consequence of policies restricting access to their baby. Nurses found this separation difficult and that it went against their philosophy of family-centred care.

Extract 7: “Our work as neonatal nurses had changed … It was heart breaking picking up the phone to update a parent on their baby's condition and hearing them breakdown with anxiety as they had not been able to see their baby for days.” (England)

This separation was considered particularly difficult for parents going through the bereavement process:

Extract 9: “Bereavement care on the NICU always has challenges in normal circumstances; this has been added to with the current Covid-19 Pandemic. Hospital visiting has been restricted to only one parent visiting the NICU per day, consequentially siblings, grandparents and friends may tragically never meet babies. This will ultimately affect parent's grief as their loved ones have never met their baby.” (England)

-

c.

Providing full developmental care

Nurses were concerned about how COVID-19 restrictions were impacting NICU babies from a developmental care perspective. They discussed this in terms of the consequences of limited human interactions from both parents and nurses, the use of PPE masks which inhibited facial expressions, and limited human touch.

Extract 10: “We now seek to maintain a balance between strict Covid-19 isolation and disinfection recommendations and the humanization of care. We must not forget how beneficial the application of Development Centred Care is … especially skin-to-skin and the strengthening of the maternal-filial bond after childbirth.” (Spain)

-

3.Vulnerability

-

a.Feeling fearful

-

a.

There was a sense of fear and anxiety in the nurse's reflections. Their fears and worries were concerned with the protection of babies they cared for, other nurses, students, themselves, and their own families. This sense of fear was linked to a feeling of uncertainty.

Extract 12: “Life as I knew it, as a neonatal nurse in a large “Level 2” NICU, meant the potential for catastrophe for the vulnerable ill term and preterm infants in my care ….As a nurse in a NICU, the uncertainty of the times is palpable …” (Ireland)

-

b.

Feeling unprepared

Nurses reflected feeling unprepared for how to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the limited and ever-changing information regarding how to prepare, manage, and respond to COVID-19 patients, as well as the resulting changes to their nursing role.

Extract 14: “It has felt very much like we have been ‘flying the plane whilst still trying to build it’.” (Australia).

Extract 15: “Sometimes It feels like we have new routines each and every week which builds up a frustration because there is not always time to learn the new routines. But we all try our best.” (Sweden)

There was also a strong sense of feeling unprepared in academic nursing environments as teaching student nurses face-to-face was abruptly changed to an online-only format.

Extract 16: “Suddenly we evacuated our offices and classrooms. Our students moved out of their dorms with no time for saying goodbye to friends. As faculty, we were thrust into using technology and online platforms that seemed foreign to many faculty who only taught in a traditional face-to-face manner … worries about success of the students ensued.” (United States)

-

c.

New demands

With the introduction of PPE and other social distance measures, nurses were now faced with new tasks, procedures, and policies.

Extract 17: “COVID19 has meant a complete shift in how I work … it has truly been a lesson in flexibility.” (New Zealand)

Wearing PPE was an obvious new demand, and some nurses reflected on the physical challenges this presented:

Extract 18: “Even for a couple of hours, makes you feel hot, dehydrated, sometimes dizzy, with fogged glasses and with a sort of shortness of breath. After you remove it bruises and pressure zones in your face can remains for hours or days.” (Portugal)

Some nurses expressed feelings of guilt about not being able to support their colleagues either on the front line (caring for COVID-19 patients), or clinically, due to shielding requirements.

Extract 20: “I am a NICU nurse and, as such, I am not on the front lines of this pandemic (yet). There is a lot of acknowledgement for healthcare workers, especially nurses, and I feel guilty for not being on the front lines. I feel guilt, and relief, and then even more guilt for feeling relief.” (United States)

As discussed above, student nurse education changed to an online platform, which meant professors and lecturers were also faced with adapting all education to an online platform (see Extract 16).

-

d.

Feeling overwhelmed

Nurses reflected on the mental and/or emotional exhaustion resulting from their increased workload. This was compounded by the uncertainty and fear that surrounded that work:

Extract 22: “The effects of the pandemic on working nurses have been considerable, and burnout has been the main manifestation. Severe staffing shortages, extra shifts, and fear of contamination have compounded the workload of nurses in NICUs.” (Brazil)

Extract 23: “Reflect. I needed to step off the Merry go round. I needed to breathe. I felt like I'd been holding my breath for 12 weeks. Locking down my ability to breath and think freely.” (England)

-

4.

Resilience

Whilst nurses experienced many challenges through the COVID-19 pandemic, their reflections also highlighted resilience. The nurses found strength in adapting to challenges and identified opportunities for growth and change.

-

a.

Personal reflection

Despite the challenges faced by neonatal nurses on the front line, they found strength and meaning, as shown in the following extracts:

Extract 25: “We are entering a new way of life – wearing masks, practicing social distancing, contact tracing - but as nurses we are also recognizing the tremendous contribution we make either at the frontline of care or education. We are making a difference in the lives of the people we serve and the students we educate.” (United States)

-

b.

Being resourceful

Nurses showed resilience to the many challenges to care provision imposed by social distancing measures by adapting their care and identifying new ways of supporting families. The use of video platforms was a key strategy they utilized:

Extract 26: “… vCreate has not only allowed parents to be closer to their babies in a different way but has given nurses a new perspective and focus on how parents can be and should be included at all times.” (England)

One nurse reflected on new ways of working that were identified when caring for a family going through the bereavement process. These included adapting an alternative room to provide end-of-life care, as well as performing new skills of sensitively taking photos of the baby, which was usually performed by a professional photography team that were prohibited from entering the unit:

Extract 28: “Alongside teamwork, effective communication and quick thinking meant mum had similar uninterrupted bereavement care on both occasions … the barriers to high quality bereavement care that Covid-19 has caused can be overcome with effective communication, teamwork and challenging current practice by different ways of working.” (England)

-

c.

Identifying new learning opportunities

Whilst the sudden shift to online learning put a strain on the teaching workload, nurses also reflected on how they adapted to this new way of teaching. Furthermore, online and virtual learning was reflected on positively as new opportunities for students were provided:

Extract 30: “… COVID19 has driven very rapid changes in higher education which I believe could be of real benefit to future neonatal nursing students. These different ways of learning could benefit part-time and distance students and offer flexibility in studying appreciated by those juggling the demands of family life and full time employment …” (England)

There were also new clinical opportunities for nurses in Northern Ireland following the re-organisation of neonatal services in line with the Covid-19 paediatric surge plans:

Extract 31: “… redeployment offered the opportunity to work at a busy Neonatal Unit, care for infants requiring a higher care level than commissioned within their home unit and offered additional experience in another Neonatal Unit.” (Northern Ireland).

-

d.

Peer emotional support

The emotional support of colleagues at home and abroad was a clear source of strength and resilience for nurses. Emotional support was achieved through sharing experiences and concerns with other nurses in their own team as well as globally.

Extract 33: “It was really inspired to feel that neonatal and paediatric palliative care were supporting one another in the globe. One of the most powerful ways of support, was keeping in touch with precious and inspiring nurses … I felt we were really as one, sharing emotions and difficulties and being inspired to move forward.” (Portugal)

-

e.

Teamwork

It was clear that resilience also came from nurses working together as part of a larger team of nurses on their unit, within their hospital, and as part of a larger community of paediatric nurses both nationally and internationally. Teamwork meant sharing information as well as working collaboratively in the provision of services.

Extract 35: “To alleviate this situation, SEEN, the Spanish Society of Neonatal Nursing, has created repositories of the evidence generated on Covid-19 and the management of the child and his family … We have a Telegram group to share doubts and concerns among neonatal nursing. And a reference position regarding care for the suspected or confirmed newborn of Covid-19 (2).” (Spain)

Discussion

In this paper we uncovered the experiences of neonatal nurses across the globe, in carrying out their roles during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This included common challenges nurses faced and strategies for overcoming them.

Changes in hospital policies made to protect babies as well as healthcare professionals and their families were described as compromising the human qualities of care that were fundamental to their approach to neonatal nursing. The concern of infecting one's own family is a significant and understandable concern for nurses caring for COVID-19 patients (Galehdar et al., 2020; Iheduru-Anderson, 2020; Liu et al., 2020). What is notable about the experiences of neonatal nurses, in contrast to adult intensive care nurses, is the tension experienced between providing protection alongside the human quality of care. In adult units, there may be a concern that the use of protective measures could potentially delay care because nurses' responses are slower, and the frequency of contact with patients may be reduced (Galehdar et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2020). In neonatal care settings, however, the tension resulting from the use of protective measures disrupts the very nature of the care that is provided to babies and their families and is fundamental to their role as family-centred care facilitators.

The role of the parent has changed beyond recognition in neonatal care (Thomas, 2008). The evolution of family-centred care (FCC), meaning families are engaged in many aspects of their baby's care and treatments (Gooding et al., 2011), has evolved into Family-Integrated care (FIcare), which supports parents in being the primary caregiver for their baby while on the neonatal unit, and nurses functioning more as a coach to parents (O'Brien et al., 2018). Family engagement with increased participation in their baby's care has demonstrated increased breastfeeding rates, improved parental satisfaction, improved long-term infant neurodevelopment and reduced parental distress. Consequently, when family engagement is compromised and opportunities for parent-infant bonding are limited, the well-being of the baby and parents are negatively impacted (Treyvaud et al., 2009; Rahkonen et al., 2014; Bastani et al., 2015; Al Maghaireh et al., 2016; Franck et al., 2019; O'Brien et al., 2018; Pineda et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2019; Pados and Hess, 2020).

The role of the neonatal nurse has adapted over time to support increased parental engagement in care. Nurses have found their change to educator, supporter and facilitator challenging, but in observing the many positive benefits from the developing models of care, have embraced their new role (Skene et al., 2019). It is therefore, unsurprising that restricting parental presence, interactions with their baby, and support from neonatal healthcare professionals was challenging for neonatal nurses globally. It is the uniqueness of this context, in which parents are considered part of the care team, which underscores the importance of limitless parental presence and involvement on neonatal units whenever possible (RCPCH, 2020), and developing strategies to overcome parental separation from their baby.

Tension experienced by neonatal nurse participants in this study of being a protector whilst still engaging parents in their baby's care, compounded nurse's vulnerability because of the feelings of distress this caused. These feelings of distress reflect similar findings for nurses and other front-line workers caring for COVID-19 patients, as well as patients in previous pandemics (Fernandez et al., 2020). Nurses report ‘feeling fearful’ (Liu et al., 2020; Nyashanu et al., 2020), ‘feeling overwhelmed’ by the workload (Iheduru-Anderson, 2020; Liu et al., 2020), and ‘feeling unprepared’ given challenges of keeping up with dynamically changing guidelines (Fernandez et al., 2020; Nyashanu et al., 2020). The physical burdens of using PPE, reported by the neonatal nurses, have also been found in the wider literature (Jia et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). The negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of nurses generally, and neonatal nurses specifically, is striking and is particularly notable in the short and powerful prose used by some of the nurses in the study (see Extract 23). Identifying strategies for managing specific challenges faced by neonatal nurses is crucial, in order to protect their well-being.

The neonatal nurse participants in the current study demonstrated their resilience through personal reflections of strength and through the identification of positive and enabling experiences. The reflections highlighted the importance of peer emotional support, a theme, which again, has been found in nurses caring for COVID-19, and past pandemic patients (Fernandez et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020). The related theme of ‘teamwork’, emphasises professional collegiality (Fernandez et al., 2020), and neonatal nurses emphasised the importance of this in terms of different networks of teams, both locally and internationally, in sharing information and providing services. The value placed on local and global networks and collaborations highlights opportunities to facilitate support and well-being while identifying new ways of service delivery, both during normality and times of pandemic.

Resilience was also demonstrated in the identification of unique resources and new learning opportunities. Key to both of these themes was the identification of new opportunities that were found within adversity, but which were also valuable tools for neonatal nurses beyond the pandemic. New learning opportunities included clinical skills, a theme also reported by nurses caring for COVID-19 patients (Jia et al., 2020). It also included on-line and virtual learning, which were considered new opportunities for flexible learning beyond the pandemic, providing student nurses with different, yet more opportunities to be trained. The identification of resources as well as the use of on-line and virtual learning platforms highlights the ability of neonatal nurses to adapt and find solutions to the challenges they faced. This can be seen through the use of video platforms to maintain contact with parents, enabling them to support parents and facilitate parent-baby bonding. Live streaming videos of babies in NICU for parents is by no means a new idea. Although the practice was perceived to be supportive of parents, nurses had previously reported fears regarding increased workload and around their own ability to use the technology (Kilcullen et al., 2020). There have also been fears expressed in the past regarding the security of the video links, but these fears far outweigh the benefits of this technology in balancing emotions generated by the pandemic. Opportunities for and acceptability of advanced technology may be a positive outcome from the pandemic, which more than likely, will continue to be utilized and will be incorporated into established practices of facilitating parental interactions with their baby and communication with the healthcare team.

The tools and strategies identified by neonatal nurses across the world demonstrate resilience and the ability to overcome challenging issues presented by a global pandemic. These are important to understand in order for professionals to prepare for subsequent phases of the COVID-19 and future pandemics.

Conclusion

During the first wave of COVID-19, neonatal nurses faced many challenges to their traditional nursing role including: feeling fearful, feeling unprepared, feeling overwhelmed and taking on new demands. These challenges were compounded by the struggle of neonatal nurses to preserve a human quality of care for the babies and families they care for in the face of new PPE demands and greatly limited parental access to the neonatal unit. In response to these challenges, neonatal nurses recall employing new tools and strategies to promote family engagement in care wherever possible, prompting re-evaluation of current practice and allowing for future improvements to be made. The study highlights the enormity of disruption when families cannot be present with their babies on the neonatal unit and emphasises the importance of ensuring that parents are central to the care provided.

Role of funding

The work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council Impact Acceleration Account at Queens University Belfast. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis or in the writing or submission of the article for publication.

Ethical approval

Approval was granted by The Queen's University Belfast Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Faculty REC) in accordance with the Proportionate Review process. Reference Number: MHLS 21_26.

Declaration of competing interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the neonatal nurses who kindly contributed their personal reflections to this project.

References

- Al Maghaireh D.a.F., Abdullah K.L., Chan C.M., Piaw C.Y., Al Kawafha M.M. Systematic review of qualitative studies exploring parental experiences in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016;25:2745–2756. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arigo D., Pagoto S., Carter-Harris L., Lillie S.E., Nebeker C. Using social media for health research: methodological and ethical considerations for recruitment and intervention delivery. Digit Health. 2018;4 doi: 10.1177/2055207618771757. 2055207618771757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastani F., Abadi T.A., Haghani H. Effect of family-centered care on improving parental satisfaction and reducing readmission among premature infants: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015;9 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/10356.5444. 8-SC04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2019;11:589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Favre G., Pomar L., Musso D., Baud D. 2019-nCoV epidemic: what about pregnancies? Lancet. 2020;395:e40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30311-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez R., Lord H., Halcomb E., Moxham L., Middleton R., Alananzeh I., Ellwood L. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses' experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020;111:103637. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck L.S., Kriz R.M., Bisgaard R., Cormier D.M., Joe P., Miller P.S., Kim J.H., Lin C., Sun Y. Comparison of family centered care with family integrated care and mobile technology (mFICare) on preterm infant and family outcomes: a multi-site quasi-experimental clinical trial protocol. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:469. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1838-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galehdar N., Kamran A., Toulabi T., Heydari H. Exploring nurses' experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID-19: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatr. 2020;20:489. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02898-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher K., Boyle B., Mancini A., Petty J. COVID-19: neonatal nursing in a global pandemic. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jnn.2021.03.011. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelinas L., Pierce R., Winkler S., Cohen I.G., Lynch H.F., Bierer B.E. Using social media as a research recruitment tool: ethical issues and recommendations. Am. J. Bioeth. 2017;17:3–14. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2016.1276644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding J.S., Cooper L.G., Blaine A.I., Franck L.S., Howse J.L., Berns S.D. Family support and family-centered care in the neonatal intensive care unit: origins, advances, impact. Semin. Perinatol. 2011;35:20–28. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iheduru-Anderson K. Reflections on the lived experience of working with limited personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 crisis. Nurs. Inq. 2020 doi: 10.1111/nin.12382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y., Chen O., Xiao Z., Xiao J., Bian J., Jia H. Nurses’ ethical challenges caring for people with COVID-19: a qualitative study. Nurs. Ethics. 2020;28(1):33–45. doi: 10.1177/0969733020944453. 969733020944453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilcullen M.L., Kandasamyb Y., Evansb M., Kanagasignamc Y., Atkinsond I., van der Valkd S., Vignarajanc J., Baxterb M. Neonatal nurses' perceptions of using live streaming video cameras to view infants in a regional NICU. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2020;26:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Knight M., Bunch K., Vousden N., Morris E., Simpson N., Gale C., O'Brien P., Quigley M., Brocklehurst P., Kurinczuk J.J. 2020. Characteristics and Outcomes of Pregnany Women Hospitalised with Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the UK: a National Cohort Study Using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Luo D., Haase J.E., Guo Q., Wang X.Q., Liu S., Xia L., Liu Z., Yang J., Yang B.X. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e790–e798. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranje K.M., Gupta G., Singh A., Bajpai S., Verma A., Jaiswal R., Pandey A., Roy A., Kaur H., Gupta A., Gautam A., Dwivedi M., Birthare A. Neonatal COVID-19 infection management. J. Neonatol. 2020;34:88–98. [Google Scholar]

- National Neonatal Audit Programme . 2019. 2019 Annual Report on 2018 Data. London. [Google Scholar]

- Nyashanu M., Pfende F., Ekpenyong M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J. Interprof. Care. 2020;34:655–661. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1792425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien K., Robson K., Bracht M., Cruz M., Lui K., Alvaro R., da Silva O., Monterrosa L., Narvey M., Ng E., Soraisham A., Ye X.Y., Mirea L., Tarnow-Mordi W., Lee S.K., O'Brien K., Lee S., Bracht M., Caouette G., Ng E., McMillan D., Ly L., Dow K., Taylor R., Monterrosa L., Canning R., Sankaran K., Bingham W., Soraisham A., el Helos S., Alvaro R., Narvey M., da Silva O., Osiovich H., Emberley J., Catelin C., St Aubin L., Warkentin T., Kalapesi Z., Bodani J., Lui K., Kho G., Kecskes Z., Stack J., Schmidt P., Paradisis M., Broadbent R., Raiman C., Wong C., Cabot M., L'Herault M., Gignac M.-A., Marquis M.-H., Leblanc M., Travell C., Furlong M., Van Bergen A., Ottenhof M., Keron H., Bowley C., Cross S., Kozinka G., Cobham-Richards V., Northrup K., Gilbert-Rogers C., Pidgeon P., McDuff K., Leger N., Thiel C., Willard S., Ma E., Kostecky L., Pogorzelski D., Jacob S., Kwiatkowski K., Cook V., Granke N., Geoghegan-Morphet N., Bowell H., Claydon J., Tucker N., Lemaitre T., Doyon M., Ryan C., Sheils J., Sibbons E., Feary A.-M., Callander I., Richard R., Orbeso J., Broom M., Fox A., Seuseu J., Hourigan J., Schaeffer C., Mantha G., Lataigne M., Robson K., Whitehead L., Skinner N., Visconti R., Crosland D., Griffin K., Griffin B., Collins L., Meyer K., Silver I., Burnham B., Freeman R., Muralt K., Ramsay C., McGrath P., Munroe M., Hales D. Effectiveness of Family Integrated Care in neonatal intensive care units on infant and parent outcomes: a multicentre, multinational, cluster- randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2018;2:245–254. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pados B.F., Hess F. Systematic review of the effects of skin-to-skin care on short-term physiologic stress outcomes in preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv. Neonatal Care. 2020;20 doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda R., Bender J., Hall B., Shabosky L., Annecca A., Smith J. Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental outcomes. Early Hum. Dev. 2018;117:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahkonen P., Heinonen K., Pesonen A.-K., Lano A., Autti T., Puosi R., Huhtala E., Andersson S., Metsäranta M., Räikkönen K. Mother-child interaction is associated with neurocognitive outcome in extremely low gestational age children. Scand. J. Psychol. 2014;55:311–318. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12133. RCPCH, 2020. COVID-19 – Guidance for neonatal settings. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene C., Gerrish K., Price F., Pilling E., Bayliss P., Gillespie S. Developing family-centred care in a neonatal intensive care unit: an action research study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2019;50:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N., Wei L., Shi S., Jiao D., Song R., Ma L., Wang H., Wang C., Wang Z., You Y., Liu S., Wang H. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. Contr. 2020;48:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treyvaud K., Anderson V.A., Lee K.J., Woodward L.J., Newnham C., Inder T.E., Doyle L.W., Anderson P.J. Parental mental health and early social-emotional development of children born very preterm. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009;35:768–777. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tscherning C., Sizun J., Kuhn P. Promoting attachment between parents and neonates despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:1937–1943. doi: 10.1111/apa.15455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Wang M., Zhu Z., Liu Y. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: a systematic review. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1759541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.T., Huang W.C., Hsieh W.S., Chang J.H., Lin C.H., Hsieh S., Lu L., Yao N.J., Fan P.C., Lee C.L., Tu Y.K., Jeng S.F. Family-Centered care enhanced neonatal neurophysiological function in preterm infants: randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 2019;99:1690–1702. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzz120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]