Abstract

Methotrexate (MTX) is known antagonist of folic acid and widely used as an anti-cancer drug. The folate receptor (FR) and reduced folate carrier are mostly responsible for internalization of methotrexate in tumor cells. Mutation in reduced folate carrier (RFC) leads to resistance against MTX in various tumor cell lines including MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. To overcome the resistance of MTX, folate receptor targeted nanoparticles have been commonly used for targeting breast tumors. The aim of the study is to determine the ability of methotrexate gold nanoparticles (MTX-GNPs) in the induction of apoptosis and to explore the molecular changes at genomics and proteomics level. Different assays like cell viability assay, cell cycle analysis, apoptosis, real-time PCR and western blot were carried out to evaluate the anti-cancer effect of MTX-Gold NPs on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. Our observations demonstrated the decrease in the percent viable cells after the treatment of MTX-GNPs, with an arrest in cell cycle at G0/G1 phase and a significant increase in apoptotic cell population and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. Folate receptor targeted MTX-GNPs showed significant cellular uptake in breast cancer cells along with significant down-regulation in expression of anti-apoptotic gene (Bcl-2) and up-regulation in expression of pro-apoptotic genes (Bax, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, APAF-1, p53). These results unveil the increased anti-cancer effect of MTX-GNPs in cancer cells.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-02718-7.

Keywords: Anticancer activity, Breast cancer, Drug delivery, Gold nanoparticles, Methotrexate

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most often diagnosed cancer worldwide with the second leading cause of cancer death in women (Patel et al. 2018). It is a malignant proliferation of epithelial cells lining the ducts and lobules of the breast with the occurrence of approximately up to 7% in women of age below 40 years and is 4% in women upto age below 35 (Alidadiyani et al. 2016; Tanaka et al. 2009). Breast cancer is classified into several intrinsic subtypes, such as the luminal A, luminal B, human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER-2)-enriched, basal-like (Triple negative), based on an immune-histochemical analysis of various receptor such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and HER-2. (Brinton et al. 2008). Despite the improved therapies and understanding of the heterogeneity of breast cancer, the overall survival rate of breast cancer patients has not improved considerably (Rani et al. 2012).

The current therapy available for breast cancer include surgical intervention, radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and immunotherapy, majorly dependent on the stage and type of cancer diagnosed (Moses et al. 2016). The common drugs used for the treatment of breast cancer are cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil capecitabine and taxanes (docetaxel and paclitaxel); belong to a group of cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents (Smorenburg et al. 2001). One of the recent approaches to treat breast cancer is the combination therapy, where multiple chemo-drugs being used together to target multiple signaling pathways and increase their anticancer efficacy (Mokhtari et al. 2017). Nevertheless, their dosage is restricted due to severe side effects like decreased blood counts, mouth ulcers, hair loss, kidney problem, fertility problems, allergic reactions and drug resistance, etc. (Khan et al. 2014).

Drug resistance remains the major factor in the occurrence of a relapse of the breast cancer along and failure of major chemotherapies including combinational chemotherapies (Yardley 2013). Tumors can be intrinsically resistant prior to chemotherapy, or resistance may be acquired during treatment by tumors that are initially sensitive to chemotherapy (Wilson et al. 2006). The occurrence of drug resistance in solid tumors has been reported upto 90% contributing more than 25% to relapse of cancer and even more to the mortality (Mabe et al. 2018). One of the approach to tackle drug resistance is to use nontoxic nanoparticles (NPs) for efficient drug delivery in tumor cells (Hassan et al. 2010; Stapf et al. 2016). Nanotechnology has a promising approach towards the treatment of breast cancer as nanoparticles can be used to improve the overall outcome of a chemotherapeutic drug into the cancer cell with the help of its site specific targeting, which prevent the toxicity in normal cells (Alidadiyani et al. 2016). Nanoparticles often referred to as nanocarriers have multifunctional properties which are being used to control the release of drugs in cells, to increase drug efficacy and decrease their resistance and side effects (Singh and Lillard 2009). The nanocarriers used so far for treatment of breast cancer includes polymeric nanoparticles, liposomes, gold nanoparticles, dendrimers, micelles, etc. (Din et al. 2017). Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) are widely used due to their small size, unique shape, inert nature, high biocompatibility, higher circulation and accumulation at the tumor site and effective delivery of drugs in chemotherapy treatment specifically in breast cancer (Daniel and Astruc 2004; Murphy 2005; Tran et al. 2013). GNPs has been previously used along with different coating (citrate, PEG, BSA, dextran, etc.) to enhance the anticancer capabilities and biocompatibility (Rizk et al. 2016; Siafaka et al. 2016).

Methotrexate (MTX) is a well-known antagonist of folic acid and has been used widely for cancer and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment (Alidadiyani et al. 2016). It has been reported that MTX impairs DNA synthesis, methylation and repair by inhibiting two key enzymes dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and thymidylate synthetase involved in purine and pyrimidine synthesis (Chan and Cronstein 2013; Zwicke et al. 2012). One of the major problems with MTX is its resistance in the breast cancer patient. MTX is known to have heterogeneous toxicity and resistance in various tumor cell lines, which results from an alteration in different transport mechanism for the influx or efflux of MTX (Brzeziñska et al. 2000; Stapf et al. 2016). Two major component responsible for internalization of MTX are folate receptor (FR) and reduced folate carrier (RFC) in tumor cells (Gaies et al. 2012). Among them, F8uR is overexpressed in many of the cancer cells and has been considering as a targeting molecule in several therapeutic strategies (Dhawan et al. 2013; Parker et al. 2005; Werner et al. 2011). RFC is proved to be overexpressed in cancer and is also a vital mechanism for the uptake of folic acid and its analogs, e.g., MTX (Matherly and Goldman 2003; Matherly et al. 2007; Spinella et al. 1995). Mutation in reduced folate carrier (RFC) protein is known to lead to resistance against chemotherapeutic drugs like MTX (Stapf et al. 2016). This is one of the reasons behind MDA-MB-231 being resistant to MTX, since FR is overexpressed in both the cell line, whereas RFC is under expressed in MDA-MB-231 cell line (Lindgren et al. 2006). Folate receptor targeted nanoparticles have been commonly used for targeting breast tumors (Wu et al. 2010). The current study aims to pursue the anticancer effect of MTX-GNPs for the two different breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 (luminal A) and MDA-MB-231 (Triple negative basal-like). Earlier studies reported that MCF-7 cells are more sensitive, whereas MDA-MB-231 cells are resistant to methotrexate due to lack of expression of the reduced folate carrier (RFC) on MDA-MB-231 cells, which are associated with internalization of methotrexate into cells (Wu et al. 2010). The present study was aimed to fabricate conjugated nanoparticles of GNPs with chemotherapeutics drug MTX and its intracellular delivery within the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells via folate receptor.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Trisodium Citrate (Na3C6H5O7), Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), Modified Eagles Medium (MEM) and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 Media, Antibiotic–antimycotic solution (10,000 U/mL penicillin, 10 mg/mL streptomycin and amphotericin-B), Fetal bovine serum (FBS), Trypsin–EDTA (Hi Media Laboratories, India). Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) (S.D. Fine-Chem Limited, Mumbai, India). 2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), Ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), Propidium iodide (PI), RNase and Triton X-100, (Hi Media Laboratories, India). Camptothecin, Cell lysis buffer, JC-1 dye, Methotrexate (MTX) and Protease inhibitor (Sigma Aldrich, India). Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). Antibodies against proteins which are associated with the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis Bcl-2, Bax, GAPDH, Caspase-3 and Caspase-9 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, India). Cell culture flasks (25 cm2), 6 and 96 well plates (Corning, India). Syringe filters 0.22 µm and filter holders (Millipore Co. Pvt Ltd., Mumbai, India). Milli Q water. All other reagents used were of analytical grade.

Synthesis of citrate capped gold nanoparticle

The citrate capped GNPs were synthesized by the classic citrate reduction method (Turkevich et al. 1951). Initially 45 mL of HAuCl4 (1 mM) was allowed to boil at 200 °C for 2–3 min. In the boiling solution, 5 mL of TSC (38.8 mM) was added rapidly. The color of the solution changes initially to black and slowly transitions to the characteristic wine-red color of GNPs. The final solution was allowed to stir for 30 min to complete the reaction and formation of a monodisperse solution of GNPs. The synthesized particles were allowed to cool down at room temperature.

Synthesis of methotrexate loaded gold nanoparticle

7.5 mg MTX was dissolved in 10 mL PBS (pH: 7.4), resulted in a yellowish color solution. Furthermore, 1 mL of MTX solution was added into 10 mL of prepared GNPs. The reaction was carried out at room temperature with stirring at 500 rpm overnight. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 1 h and the pellet was resuspended in PBS (pH: 7.4).

Characterization of nanoparticle

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis

Hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of GNPs and MTX-GNPs was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Zetasizer Nano-ZS, Model ZEN3600 equipped with 4.0 mW, 633 nm laser; Malvern UK) at 25 °C with a 173°scattering angle. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

UV–Vis spectroscopy analysis

The Absorption spectra of prepared GNPs, free MTX and MTX-GNPs were taken using UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Synergy-HT multiplate Reader, BioTek, USA).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging

The morphological analysis of the synthesized GNPs and MTX-GNPs was done by transmission electron microscope (JEOL, JEM1400 plus, Japan) at accelerating voltage 120 kV. The sample was prepared by placing synthesized nanoparticle solutions on a copper grid, dried at room temperature and finally images were captured for size analysis.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic spectrum of free MTX and MTX-GNPs were recorded using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum-Two™ (USA) instrument.

Drug release kinetics

The release of methotrexate from the GNPs surface was analyzed using spectral analysis at 360 nm. The synthesized MTX-GNPs (10 mL) were transferred into a dialysis bag (Molecular weight: 12,400) and dialyzes against 1000 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) with stirring at 100 rpm for 24 h at 37 °C. The sample was taken out for analysis at different time points and replaced with the fresh buffer solution. The relative percentage of the methotrexate release was calculated.

A is the amount of drug in the release medium. B is the amount of drug loaded on the nanoparticle

Cell culture and treatment of nanoparticle

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were procured from National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS), Pune, India. Modified Eagles Medium was used for MCF-7 cells, while RPMI-1640 for MDA-MB-231 cells at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The media were supplemented with 10% FBS (heat inactivated), 0.2% sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) and 10 mL/L antibiotic and antimycotic solution. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity potential of MTX-GNPs was determine with various dilution in culture media. In all the experiments culture medium without nanoparticles served as a control.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic effect of the free MTX and MTX-GNPs in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines was assessed by the MTT assay as described by Mosmann (Mosmann 1983). Briefly, 100 µL of culture medium was used to seed 1 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate. After 24 h of incubation cells were treated with free MTX at concentration ranges from 400 to 1600 µM and MTX-GNPs at concentration 50–500 µM for 24 h. Assay reagents were also tested using a cell-free system to check the effect of nanoparticles, where nanoparticles alone were incubated with the assay reagents, including dye and buffers. The absorbance of the plate was recorded at wavelength 595 nm using the software Gen5 in SYNERGY-HT multiplate reader (Bio-Tek, USA).

Cellular uptake analysis

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were plated in 6 well plates at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well. After 24 h of incubation, MTX-GNPs of different concentrations (25–250 µM) were added into the wells and incubated for 6 h. After exposure, treatment was removed and cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in 500 µL of PBS and the uptake of particles was analyzed by comparing the SSC (side scatter intensity) of the treated cells in flow cytometer (FACSCalibur, BD Bioscience, CA, and USA).

Cell cycle progression analysis

The DNA content in the cell cycle was analyzed with the help of flow cytometry as the method suggested by Patel et al. (2016). Both the breast cancer cells at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well were seeded in a six-well plate and treated with different MTX-GNPs concentrations (25–250 µM) for 24 h. Treatment of ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) at concentration (6.8 mM for 3 h) has been used as positive control. After the treatment, the cells were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol (at − 20 °C for 30 min). Cells were further lysed using 1 ml of 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS at 4 °C for 30 min. Cells were then centrifuged and re-suspended in 500 µL of PBS comprising 20 µL RNase (10 mg/mL) for 30 min at 37 °C. Finally, cells were stained using 10 µL propidium iodide (1 mg/mL) in 500 µL PBS for 10–15 min at 4 °C and analyzed using FACS (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences, CA).

Apoptosis markers

Mitochondrial membrane potential

To assess the change in mitochondrial membrane potential a lipophilic cationic dye JC-1 was used. JC-1 dye is known to enter into mitochondria selectively, and change the color reversibly from red to green fluorescence, when there is a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (Meghani et al. 2018). Briefly, both the cancer cell lines were seeded in a six-well plate (3 × 105 cells/well) and allowed to grow for 24 h and then exposed to MTX-GNPs for (25–250 µM) for 24 h. In this assay, the positive control used was camptothecin (1 μM). At the end of treatment, cells were washed with PBS followed by staining with JC-1 dye (10 μM) for 15 min at 37 °C. The cells were analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer.

Annexin V binding assay

Apoptotic cells were screened by staining with PI and FITC-Annexin V as per the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well were plated in a 6 well culture plate and incubate for 24 h. Cells were treated with MTX-GNPs at different concentrations (25–250 µM) for 24 h. The positive control for the assay was Camptothecin (1 μM). At the end of treatment, cells were collected and washed with PBS and resuspended in 500 µL binding buffer having 5 μL of FITC-Annexin V and PI and kept at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. After incubation, each sample were acquired in BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analyzed for apoptotic cells.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured and were treated with free MTX (100 µM) and MTX-GNPs (100 µM) for 24 h. After treatment, total RNA from the cells were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). RNA yield and integrity were determined using the SYNERGY-HT multiwall plate reader (Bio-Tek, USA) with Gen5 software. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with two micrograms of RNA isolated from different samples using a Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was performed using cDNA from each replicate and gene-specific primers with a powerup™ SYBR® Green master mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) in the Quant studio 5 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The mRNA levels of above different genes were quantified by measuring the threshold cycle (Ct). The details of primer pairs used for different genes are given in supplementary data, Table 1.

Immunoblot analysis

The cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 were treated with 100 µM concentration of free MTX and MTX-GNPs for 24 h. After removal of treatment, cells were collected and lysed in lysis buffer. (1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris–HCl at pH 8 and containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)). Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay as per the protocol described by Bradford (1976). Equal amount of protein (30 µg) from control and treated groups were resolved on glycine-SDS–Polyacrylamide (8%) and transferred to a PVDF membrane by electroblotting. The membrane was dried to fix the protein and blocked with skimmed milk. After washing, the membrane was incubated with a different primary antibody specific to Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase-3, Caspase-9 and GAPDH (Invitrogen) separately for overnight at 40 °C. Finally, secondary antibody incubation was completed and protein bands were detected using chemiluminescence analysis, carried out in Image Quant LAS 500 software (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Sweden).

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried out in triplicates and the results were presented as means ± standard error mean (SEM). ANOVA was used for statistical analysis followed by Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparison tests from Graph Prism-8.0. In all the cases, the p-value less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of GNPs and MTX-GNPs

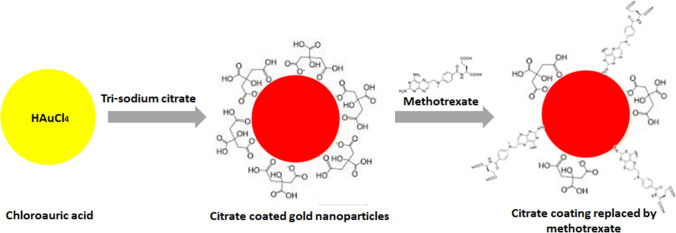

MTX-GNPs were synthesized by the addition of citrate coated GNPs in the MTX solution, as shown in Fig. 1. The loading of MTX on GNPs was determined using various techniques such as dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis, UV–Vis measurement, TEM and FTIR. The average hydrodynamic size of citrate coated GNPs and MTX-GNPs was 17.70 nm and 30.16 nm, respectively. The observed average zeta potential of citrate coated GNPs and MTX-GNPs was − 26.6 mV and − 11.6 mV, respectively (Supplementary data: Table 2). The increased in the mean the hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of MTX-GNPs compared to citrate coated GNPs could be contributed to the replacement of citrate ions with MTX.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representing the synthesis of methotrexate gold (MTX-GNPs) nanoconjugate

UV–Vis spectrophotometry studies were performed to assess the total loading of MTX on GNPs. Citrate coated GNPs of size 15 nm are reported to show absorption peak at 520 nm (Murawala et al. 2014). However, the loading of MTX on GNPs lead to peak shift of 10 nm as the formulated nanoconstruct showed a peak at 530 nm (Fig. 2a). This shift is a result of a change in the dielectric constant of GNPs due to MTX loading on the external surface (Cumberland and Strouse 2002).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of methotrexate gold (MTX-GNPs) nanoconjugate. a UV–Vis spectrum of GNPs (Blue), free MTX (Orange) and MTX-GNPs (Green). b FTIR spectra of free MTX (Blue) and MTX-GNPs (Orange) in the range 400–4000 cm−1. c TEM images of citrate coated GNPs (left) and MTX-GNPs (right). (Scale bar = 100 nm)

The size and morphological analysis of the synthesized particles were done using TEM. It has been observed that both the nanoparticles are spherical in shape and monodispersed in a size range of 15–20 nm (Fig. 2b). The fact that both the nanoparticles are of same size range leads to the conclusion that the loading of MTX on GNPs is by replacement of citrate ion. Furthermore, to conform the loading of MTX on the GNPs, the FTIR spectrum of free MTX was compared with MTX-GNPs. Peaks near 1073 cm−1, 1693 cm−1 and 3440 cm−1 confirms the presence of MTX loaded on GNPs (Fig. 2c)(Tran et al. 2013).

Drug release kinetics

Drug release kinetics of MTX from GNPs at different time points were studied using UV–Vis spectroscopy by taking the absorbance of MTX at 360 nm. Earlier studies have reported that citrate coated GNPs are very good for biomedical applications (Chhour et al. 2016). Our observations revealed that it takes over 24 h for a drug to be released from the GNPs surface at pH 7.4. Additionally, it has been observed that more than 90% of MTX gets released in PBS (pH 7.4) in 24 h (Data not shown).

Cytotoxicity assessment of MTX-GNPs by MTT assay

The breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 were exposed to both free MTX (400–1600 μM) and MTX-GNPs (50–500 μM) for 24 h. Although both the cell lines have been reported to react differently to the MTX, the results observed with respect to the reduction in cell viability in both the tumor cell line were similar. While MCF-7; a luminal A type cell line is known for its sensitivity to the MTX and MDA-MB-231; a triple negative cell line has been previously reported to be resistance to the MTX (Lindgren et al. 2006; Stapf et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2010). It was observed that free MTX is effective at a concentration of 1600 μM which results in a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in cell viability. At this concentration the observed cell viability is 63.79% and 81.28% in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively, after 24 h. The difference in both the cell line could be attributed to the inherent MTX resistance in MDA-MB-231 cells. However, MTX-GNPs at a concentration 100, 250 and 500 μM induces a significant (p < 0.001) reduction in the cell viability to 55.87%, 43.04% and 25.59%, respectively, after 24 h treatment in MCF-7 cells. In contrast, MTX-GNPs even at the concentrations of 100, 250 and 500 μM induces a loss to 54.31%, 37.40%, 25.84% of cell viability in MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h (Fig. 3a). This result proves that the GNPs as a carrier can successfully reduce the concentration of MTX to avoid its side effects, along with better cytotoxicity in both the cell types. Our observations also revealed that the triple negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, which carry an aggressive phenotype, responded similarly to the treatment than the less aggressive, estrogen receptor positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Fig. 3.

Cellular response of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. a Cytotoxicity of varying concentrations of free MTX and MTX-GNPs in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 24 h. b Cellular uptake of MTX-GNPs (25–250 µM) in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 6 h. Values represents mean ± S.E. of three experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001)

Cellular internalization of MTX-GNPs using flow cytometry

Internalization of MTX-GNPs in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 was performed with flow cytometer. Dot plots revealed significant (p < 0.001) concentration dependent uptake of MTX-GNPs in MCF-7, while the concentration dependent uptake in MDA-MB-231 was only up to 100 μM concentration after 6 h incubation (Fig. 3b). The higher uptake of MTX-GNPs was found in MCF-7 cells than MDA-MB-231 cells. This could be attributed to the fact that MDA-MB-231 is known to show resistant against MTX, while as MCF-7 is more sensitive towards MTX. In a recent study investigated that GNPs were taken up by preferentially by cancer cells than the normal cells (Hu et al. 2015). Also, it has been reported that free MTX is mainly taken up by cells via FR and RFC, whereas uptake of MTX-GNPs was through mainly by FR. This internalization of MTX-GNPs via FR mediated endocytosis also proves the adequate binding of MTX on the surface of GNPs (Chan and Cronstein 2013; Genestier et al. 2000; Stapf et al. 2016). Since MDA-MB-231 is known to show or develop resistance against MTX, this formulation could be the potential solution against it.

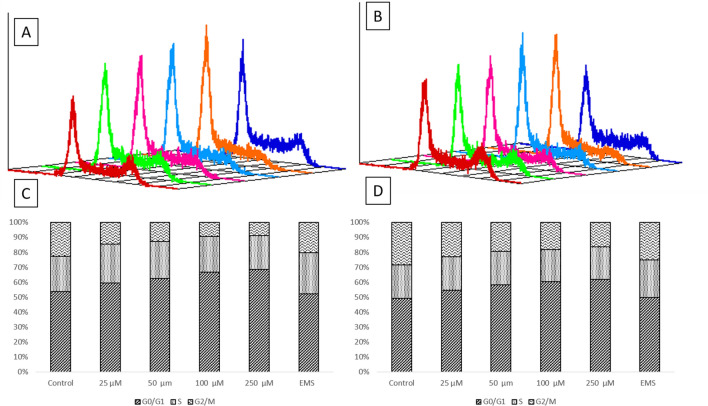

Cell cycle analysis

It has been reported that the MTX affect the cell by inhibiting the progression of G1 to S phase of cell cycle and arresting cells in the late G1–S boundary (Costantini et al. 2010). In the present study the cell cycle analysis was done using flow cytometry, where the percentage number of cells in a particular stage of cell division is represented by the amount of DNA present in that stage of the cell. In our study, after the treatment of MTX-GNPs with different concentrations (25–250 μM) for 24 h, the concentration dependent increase in cell cycle arrest was observed in the G0/G1 phase as compared to control in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. This arrest was accompanied by a significant decrease in the percentage of cells in the G2/M phase. The percentage number of cells present in the G0/G1 phase in control was 53.95% and 49.5%, respectively, in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. However, in cells treated with MTX-GNPs at 250 μM concentration for 24 h it was 68.75% and 61.93% cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, respectively (Fig. 4). That means only 20–23% of cells have been able to move on to S and G2/M phase in both the cell lines. Thus, the concentration dependent study of MTX-GNPs on cell cycle progression in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells showed G0/G1-S phase arrest.

Fig. 4.

Cell cycle progression analysis in a MCF-7 and b MDA-MB-231 cells after treated of MTX-GNPs (25–250 µM) for 24 h. The last cell cycle progression (dark blue) is for ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) and it shows prolonged S phase and shorter G0/G1 phase. Bar graphs represents the percent cell distribution in different phases of cell cycle (G1, S and G2/M) after treatment with MTX-GNPs for 24 h c MCF-7 and d MDA-MB-231

Apoptosis markers

Further to explore the possible mechanism of cell death different apoptotic markers such as mitochondrial membrane potential, expression of annexin V and genomic and proteomic approach were used. The process of metastasis are known to be involved in the alteration of apoptotic pathways (Jiang et al. 2015). Apoptosis is a very complex process that includes a variety of different signaling pathways and results into cell death. Apoptosis can be induced via caspase dependent and caspase independent pathways. However, studies have been reported that caspase dependent pathway is more commonly activated in all the cancers, while Caspase-3 is the central player in apoptotic pathway (Jin and El-Deiry 2005). It was observed that the free methotrexate increased the expression of the apoptotic genes but when conjugated with the nanoparticles, it showed more positive gene expression fold change. It is reported that methotrexate does not directly stimulate apoptosis but actually primes the cells for prominently improved sensitivity to apoptosis through either mitochondrial or death receptor routes by a Jun N-terminal kinase [JNK]-dependent procedure (Spurlock et al. 2011). Our observations are also in accordance to the reported data, where we observed that the MTX-GNPs induced the apoptosis in breast cancer cells via caspase dependent pathway.

Mitochondrial membrane potential

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with MTX-GNPs at various concentrations (25–250 µM) for 24 h to observe an alteration in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). A concentration dependent significant (p < 0.05, p < 0.001) fold increase in green fluorescence 1.66 ± 0.14 and 1.98 ± 0.14 was observed in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively, at 250 µM concentration, suggesting the involvement of the mitochondria in the activation of apoptotic pathway in both the breast cancer cell type (Fig. 5). As the electron transport system of the cells is located at mitochondria, any disturbance in the mitochondrial membrane potential lead to the altered respiration and overall cellular metabolism. Also, it specifies the activation of the intrinsic pathway for apoptosis. Mitochondrial membrane potential is one way to confirm the occurrence of apoptosis instead of necrosis (Meghani et al. 2018; Osellame et al. 2012).

Fig. 5.

MTX-GNPs (25–250 µM) induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 24 h. Bar graph represents the fold increase of JC-1 monomer positive cells (MMP loss). Camptothecin (1 µg/mL) was used as positive control. Values represent mean ± S.E. of three experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001)

Annexin V binding assay

Apoptotic cells and necrotic cells were identified with the help of annexin V-PI dual staining assay. Our data suggested the presence of apoptotic cells as evident by a reduction in the MMP after the 24 h treatment of MTX-GNPs (25–250 µM). An increase in the apoptotic cells were observed from 1.62 ± 0.59 (50 µM), 1.72 ± 0.44 (100 µM), 2.12 ± 0.28 (250 µM) fold in MCF-7 cells, whereas 1.28 ± 0.2 (250 µM) fold in MDA-MB-231 cells, as compared to control (Fig. 6). This study proves the occurrence of apoptosis as a mode of cytotoxicity by MTX-GNPs, which is in line with the other reported study (Marczak et al. 2015). Furthermore, to assess the mechanism of apoptosis by MTX-GNPs, induction of key apoptotic marker genes and proteins were further examined using real time PCR and western blot analysis.

Fig. 6.

Methotrexate gold (MTX-GNPs) nanoconjugate induced apoptosis in MCF7 and MDA MB cells as assessed by Annexin V-PI dual staining assay using flow cytometry. a MCF-7 cells untreated b–e MCF-7 cells treated with various concentrations of MTX-GNPs conjugates f MCF-7 cells treated with 1 µg/mL camptothecin g MDA-MB-231cells untreated h–k MDA-MB-231 cells treated with various concentrations of MTX-GNPs conjugates l MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 1 µg/mL camptothecin. m The bar graph depicts the fold increase in the apoptotic cells with respect to control cells. Values represent mean ± S.E. of three experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001)

Real-time PCR analysis for apoptotic genes

We assessed the difference in cycle threshold (ΔCt) between the treated group and the vehicle control for each gene. When cells were treated with MTX-GNPs, the level of anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 level decreased in both the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, 0.36 and 0.71 folds, respectively. Down-regulation of Bcl-2 is reported to stimulate the production of oxidative stress, which is known to cause tissue damage and apoptosis. During apoptosis, the down regulation of anti-apoptotic is accompanied by the up-regulation of pro-apoptotic gene Bax, which in here was up-regulated upto 3.62 folds and 1.98 folds in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively. The up-regulation of Bax has generally followed the activation of Caspase-9 and APAF-1, both of which were observed to be up-regulated here. Caspase-9 and APAF-1 both are known to activate Caspase-3. The fold increase in the level of Caspase-3 was observed to be 7.95 and 4.16 in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively (Fig. 7). This activation pathway resulting in apoptosis is referred to as the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. The observed fold increase in p53 was assessed to verify the arrest observed in cell cycle analysis. The cell cycle arrest in G1–S phase is due to up-regulation of the p53 gene which via activation of p21 is known to cause cell cycle arrest in G1–S phase.

Fig. 7.

Real time PCR analysis of apoptotic genes (Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, APAF-1 and p53) in a MCF-7 and b MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 24 h with free MTX (100 µM) and MTX-GNPs (100 µM). The representative data of at least three independent experiments mean ± S.E. are shown (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001)

Western blot analysis

The level of the apoptotic proteins was quantified using western blot and the results observed were in correlation with the genomic studies. Our experimental data suggested a concentration-dependent increase in the expression of Bax (pro-apoptotic protein) and a decrease in levels of Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic protein) after 24 h of exposure (Fig. 8). This could be due to increased mitochondrial membrane potential, which results in the modulation in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio leading to the release of cytochrome c, which further binds with the apoptotic protease-activating factor (APAF-1) resulting in the creation of an apoptosome. As mention earlier, Bax activates Caspase-9, which in turn along with APAF-1 activates Caspase-3, leading to a cascade of events that cause cell death in both the breast cancer cells (Bagci et al. 2006; George et al. 2016). MTX drug have earlier been reported to induce apoptosis via DNA damage and ROS mediated Bax/Bcl-2-cytochrome-c release cascading pathway in ovarian adenocarcinoma SKOV-3 cells and we expect that our MTX-GNPs have also been activated the signaling pathways via these molecules (AlBasher et al. 2019). A schematic for MTX-GNPs induced apoptosis in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells is represented in supplementary data, Fig. 1.

Fig. 8.

Bar graphs represents the Immunoblot analysis of apoptotic proteins (Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, Caspase-9) and control protein (GAPDH) in a MCF-7 and b MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 24 h with free MTX (100 µM) and MTX-GNPs (100 µM). c Also shown is a western blot for GAPDH as a loading control. The representative mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments are shown (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001)

Conclusion

The metal based nanoparticles like gold, silver, iron oxide and zinc oxide have anticancer activity against many malignancies like colon cancer. It is reported that the metal oxide based nanoparticles induces oxidative stress and ROS production that subsequently leads to cell-cycle arrest in the G0 phase and apoptosis in various organ specific cell lines (Dasgupta et al. 2018; Ranjan et al. 2020; Sharma et al. 2011, 2012; Shukla et al. 2011; Spurlock et al. 2011). Resistance in MDA-MB-231 cells has been reported previously for chemotherapeutic drugs MTX, along with the sensitivity of MTX in MCF-7 cells. Our study using the methotrexate gold (MTX-GNPs) nanoconjugate demonstrates that both the cells (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231) are equally sensitive to the drug. Different cellular responses were observed, when the cells were exposed to same concentration of MTX drug alone. However, the response was similar in both the cell lines when treated with MTX-GNPs; showing less than 50% viability at 250 µM concentration. MTX-GNPs induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in both the cell lines leading to cell death via the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Fold increase in pro-apoptotic RNA and protein levels and fold decrease in anti-apoptotic RNA and proteins proved the occurrence of apoptosis in breast cancer cells.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India [Grant number BT/PR10414/PFN/20/961/2014] and DST SERB [Grant number EMR/2016/005286]. Financial assistance by The Gujarat Institute for Chemical Technology (GICT) for the Establishment of a Facility for environmental risk assessment of chemicals and nanomaterials is also acknowledged. Pal Patel would like to acknowledge SERB, DST, Government of India and CII under Prime Minister Fellowship Scheme for Doctoral Research for providing fellowship.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no competing interest.

References

- AlBasher G, et al. Methotrexate-induced apoptosis in human ovarian adenocarcinoma SKOV-3 cells via ROS-mediated bax/bcl-2-cyt-c release cascading. OncoTargets Therapy. 2019;12:21. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S178510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alidadiyani N, Salehi R, Ghaderi S, Samadi N, Davaran S. Synergistic antiproliferative effects of methotrexate-loaded smart silica nanocomposites in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44:603–609. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2014.975235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagci E, Vodovotz Y, Billiar T, Ermentrout G, Bahar I. Bistability in apoptosis: roles of bax, bcl-2, and mitochondrial permeability transition pores. Biophys J. 2006;90:1546–1559. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton LA, Sherman ME, Carreon JD, Anderson WF. Recent trends in breast cancer among younger women in the United States. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1643–1648. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziñska A, Wiñska P, Balinska M. Cellular aspects of folate and antifolate membrane transport. Acta Biochimica Polonica-English Edition. 2000;47:735–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Mechanisms of action of methotrexate. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2013;71:S5–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhour P, Naha PC, Cheheltani R, Benardo B, Mian S, Cormode DP. Nanomaterials in pharmacology. New York: Springer; 2016. Gold nanoparticles for biomedical applications: synthesis and in vitro evaluation; pp. 87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini DL, Villani DF, Vallis KA, Reilly RM. Methotrexate, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin radiosensitize HER2-amplified human breast cancer cells to the auger electron-emitting radiotherapeutic agent 111In-NLS-trastuzumab. J Nuclear Med. 2010;51:477–483. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumberland S, Strouse G. Analysis of the nature of oxyanion adsorption on gold nanomaterial surfaces. Langmuir. 2002;18:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M-C, Astruc D. Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chem Rev. 2004;104:293–346. doi: 10.1021/cr030698+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N, Ranjan S, Mishra D, Ramalingam C. Thermal Co-reduction engineered silver nanoparticles induce oxidative cell damage in human colon cancer cells through inhibition of reduced glutathione and induction of mitochondria-involved apoptosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;295:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan D, et al. Targeting folate receptors to treat invasive urinary bladder cancer. Can Res. 2013;73:875–884. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Din F, Aman W, Ullah I, Qureshi OS, Mustapha O, Shafique S, Zeb A. Effective use of nanocarriers as drug delivery systems for the treatment of selected tumors. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:7291. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S146315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaies E, Jebabli N, Trabelsi S, Salouage I, Charfi R, Lakhal M, Klouz A. Methotrexate side effects: review article. J Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Genestier L, Paillot R, Quemeneur L, Izeradjene K, Revillard J-P. Mechanisms of action of methotrexate. Immunopharmacology. 2000;47:247. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George BP, Abrahamse H, Parimelazhagan T. Caspase dependent apoptotic activity of Rubus fairholmianus Gard. on MCF-7 human breast cancer cell lines. J Appl Biomed. 2016;14:211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M, Ansari J, Spooner D, Hussain S. Chemotherapy for breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:1121–1131. doi: 10.3892/or_00000963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Niestroj M, Yuan D, Chang S, Chen J. Treating cancer stem cells and cancer metastasis using glucose-coated gold nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2015;10:2065. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S72144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang WG, et al. Seminars in cancer biology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. Tissue invasion and metastasis: molecular, biological and clinical perspectives; pp. S244–S275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, El-Deiry WS. Overview of cell death signaling pathways. Cancer Biol Therapy. 2005;4:147–171. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.2.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Rashid R, Murtaza G, Zahra A. Gold nanoparticles: synthesis and applications in drug delivery. Trop J Pharm Res. 2014;13:1169–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren M, et al. Overcoming methotrexate resistance in breast cancer tumour cells by the use of a new cell-penetrating peptide. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabe NW, Fox DB, Lupo R, Decker AE, Phelps SN, Thompson JW, Alvarez JV. Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor Par-4 promotes chemoresistance in recurrent breast cancer. J Clin Investig. 2018;128:4413–4428. doi: 10.1172/JCI99481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczak A, Denel-Bobrowska M, Rogalska A, Łukawska M, Oszczapowicz I. Cytotoxicity and induction of apoptosis by formamidinodoxorubicins in comparison to doxorubicin in human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;39:369–383. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matherly LH, Goldman D. Membrane transport of folates. Vitamins Hormones. 2003;66:405–457. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(03)01012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matherly LH, Hou Z, Deng Y. Human reduced folate carrier: translation of basic biology to cancer etiology and therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:111–128. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani N, Patel P, Kansara K, Ranjan S, Dasgupta N, Ramalingam C, Kumar A. Formulation of vitamin D encapsulated cinnamon oil nanoemulsion: its potential anti-cancerous activity in human alveolar carcinoma cells. Colloids Surf B. 2018;166:349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari RB, Homayouni TS, Baluch N, Morgatskaya E, Kumar S, Das B, Yeger H. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:38022. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses S, Edwards V, Brantley E. Cytotoxicity in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, without harming MCF-10A healthy cells. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2016;7:2. [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murawala P, Tirmale A, Shiras A, Prasad B. In situ synthesized BSA capped gold nanoparticles: effective carrier of anticancer drug methotrexate to MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mater Sci Eng. 2014;C34:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CJ, et al. Anisotropic metal nanoparticles: synthesis, assembly, and optical applications. New York: ACS Publications; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osellame LD, Blacker TS, Duchen MR. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial function. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker N, Turk MJ, Westrick E, Lewis JD, Low PS, Leamon CP. Folate receptor expression in carcinomas and normal tissues determined by a quantitative radioligand binding assay. Anal Biochem. 2005;338:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P, Kansara K, Senapati VA, Shanker R, Dhawan A, Kumar A. Cell cycle dependent cellular uptake of zinc oxide nanoparticles in human epidermal cells. Mutagenesis. 2016;31:481–490. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gew014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P, Meghani N, Kansara K, Kumar A. Nanotherapeutics for the treatment of cancer and arthritis. Curr Drug Metab. 2018 doi: 10.2174/1389200220666181127102720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani D, Somasundaram VH, Nair S, Koyakutty M. Advances in cancer nanomedicine. J Indian Inst Sci. 2012;92:187–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan S, Dasgupta N, Mishra D, Ramalingam C (2020) Involvement of Bcl-2 activation and G1 cell cycle arrest in colon cancer cells induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized by microwave-assisted hybrid approach. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8:606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rizk N, Christoforou N, Lee S. Optimization of anti-cancer drugs and a targeting molecule on multifunctional gold nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2016;27:185704. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/27/18/185704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Anderson D, Dhawan A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and genotoxicity in human liver cells (HepG2) J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7:98–99. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2011.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Anderson D, Dhawan A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative DNA damage and ROS-triggered mitochondria mediated apoptosis in human liver cells (HepG2) Apoptosis. 2012;17:852–870. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla RK, Kumar A, Pandey AK, Singh SS, Dhawan A. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis in human keratinocyte cells. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7:100–101. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2011.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siafaka P, Üstündağ Okur N, Karavas E, Bikiaris D. Surface modified multifunctional and stimuli responsive nanoparticles for drug targeting: current status and uses. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1440. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Lillard JW., Jr Nanoparticle-based targeted drug delivery. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;86:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smorenburg C, Sparreboom A, Bontenbal M, Verweij J. Combination chemotherapy of the taxanes and antimetabolites: its use and limitations. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2310–2323. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinella MJ, Brigle KE, Sierra EE, Goldman ID. Distinguishing between folate receptor-α-mediated transport and reduced folate carrier-mediated transport in L1210 leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7842–7849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurlock CF, III, et al. Increased sensitivity to apoptosis induced by methotrexate is mediated by JNK. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2606–2616. doi: 10.1002/art.30457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapf M, Poempner N, Teichgraeber U, Hilger I. Heterogeneous response of different tumor cell lines to methotrexate-coupled nanoparticles in presence of hyperthermia. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:485. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S94384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Decuzzi P, Cristofanilli M, Sakamoto JH, Tasciotti E, Robertson FM, Ferrari M. Nanotechnology for breast cancer therapy. Biomed Microdev. 2009;11:49–63. doi: 10.1007/s10544-008-9209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran NTT, Wang T-H, Lin C-Y, Tai Y. Synthesis of methotrexate-conjugated gold nanoparticles with enhanced cancer therapeutic effect. Biochem Eng J. 2013;78:175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Turkevich J, Stevenson PC, Hillier J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1951;11:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Werner ME, et al. Folate-targeted nanoparticle delivery of chemo-and radiotherapeutics for the treatment of ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8548–8554. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, Longley D, Johnston P. Chemoresistance in solid tumours. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:x315–x324. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Shah A, Patel N, Yuan X. Development of methotrexate proline prodrug to overcome resistance by MDA-MB-231 cells. Bioorganic Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:5108–5112. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley DA. Drug resistance and the role of combination chemotherapy in improving patient outcomes. Int J Breast Cancer. 2013;2013:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2013/137414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicke GL, Ali Mansoori G, Jeffery CJ. Utilizing the folate receptor for active targeting of cancer nanotherapeutics. Nano Rev. 2012;3:18496. doi: 10.3402/nano.v3i0.18496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.