Abstract

Objective

Family health history is important to clinical care and precision medicine. Prior studies show gaps in data collected from patient surveys and electronic health records (EHRs). The All of Us Research Program collects family history from participants via surveys and EHRs. This Demonstration Project aims to evaluate availability of family health history information within the publicly available data from All of Us and to characterize the data from both sources.

Materials and Methods

Surveys were completed by participants on an electronic portal. EHR data was mapped to the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership data model. We used descriptive statistics to perform exploratory analysis of the data, including evaluating a list of medically actionable genetic disorders. We performed a subanalysis on participants who had both survey and EHR data.

Results

There were 54 872 participants with family history data. Of those, 26% had EHR data only, 63% had survey only, and 10.5% had data from both sources. There were 35 217 participants with reported family history of a medically actionable genetic disorder (9% from EHR only, 89% from surveys, and 2% from both). In the subanalysis, we found inconsistencies between the surveys and EHRs. More details came from surveys. When both mentioned a similar disease, the source of truth was unclear.

Conclusions

Compiling data from both surveys and EHR can provide a more comprehensive source for family health history, but informatics challenges and opportunities exist. Access to more complete understanding of a person’s family health history may provide opportunities for precision medicine.

Keywords: Family health history, precision medicine, health surveys, electronic health records

INTRODUCTION

Family health history is long recognized to be important in clinical care and precision medicine.1–3 Through family history, healthcare providers can recognize the potential risk of disease in an individual based on inheritance. By understanding an individual’s disease risk, early interventions can help mitigate or prevent familial disease occurrence. Harnessing informatics tools like predictive modeling and machine learning models can significantly improve the precise care that we deliver to patients.

Prior studies show gaps in data from electronic health record (EHR) structured fields that are moderately assisted by free text extraction; however, there are significant limitations in routine acquisition of family health history from EHRs.4–6 Family health history can also be collected through patient surveys. Patient surveys or questionnaires show promise in obtaining family history.3,7,8 However, similar to EHRs, patient surveys may collect limited data.7 While both EHRs and patient surveys could have more complete family health history, single-center studies combining data sources demonstrate limitations.9,10 There is a paucity of literature describing a publicly available using both data sources to describe family history of a large diverse cohort across the United States.

The All of Us Research Program (All of Us) is recruiting 1 million or more participants reflecting the rich diversity of the U.S. population to advance the science of precision medicine (https://www.researchallofus.org/).11 All of Us is collecting unique family health history information using online surveys and EHR data from participants recruited at multiple healthcare organizations across the country. Both data types are mapped to the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) common data model (https://github.com/OHDSI/CommonDataModel/wiki). These data are then curated with algorithms to develop a clean dataset, followed by privacy rules to ensure participant de-identification. Additionally, fields containing identifiable information are removed. Curated data are deposited into the All of Us Researcher Workbench, a cloud-based analytic platform for researchers which includes custom graphical interface data selection tools and client support for Python or R in Jupyter notebooks. All of Us developed a set of Demonstration Projects to highlight the ability of the initial launch data and tools to answer pertinent research questions as well as address limitations of the data.12 This Demonstration Project aims to evaluate the availability of family health history information within the All of Us registered tier data and to characterize the structured data elements from both data sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed data from the September 2019 All of Us registered tier version R2019Q4R3. This dataset included family health history surveys administered to participants between May 2018 and September 30, 2019, as well as EHR data between 1980 and 2019. For the purposes of this project, an observation is the mention of the presence or absence of a family history of a certain disease. Each participant can have multiple family history observations, as they may have more than 1 family health history condition in more than 1 relative. We analyzed data at both the participant and observation levels.

The All of Us Research Program Institutional Review Board has established that registered tier data available on the Researcher Workbench (https://workbench.researchallofus.org/) meet criteria for non–human subjects research. Therefore, this demonstration project did not require Institutional Review Board review.

Surveys

All of Us collects survey data through a participant portal which can be accessed through the Internet on a desktop computer, or via a downloadable app on a tablet or smartphone. The development and launch of these surveys are described elsewhere.13 There are 6 surveys: the first 3 are available when a participant enrolls, and the remaining surveys, including family health history, become available 90 days after initial enrollment.

Participants are asked questions about the health history of first-degree blood relatives, including mother, father, siblings, and children, as well as grandparents (Supplementary Appendix 1). Each response to a question that refers to a disease is considered an independent observation of family health history from the survey. Diseases are grouped by categories that cover most organ systems, including heart, lung, gastrointestinal, and endocrine. A participant may skip questions or respond “prefer not to answer” or “don’t know,” as well as “no blood-related siblings” and “no blood-related children.” The full survey is located online (https://www.researchallofus.org/data-sources/survey-explorer/). We excluded survey participants who indicated that they did not know any family health history and those who skipped every question. The family health history survey was designed to focus on medically actionable genetic disorders, guided by the list of genes/disorders recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics for reporting secondary findings from genome sequencing.14 Therefore, all diseases have a corresponding question for each relative and can be mapped from the survey to the disease in a structured manner (ie, a participant can select any of the diseases in the list for each relative in the family health history survey).

Electronic health records

EHR data about family health history were mapped to OMOP using Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) and International Classification of Diseases codes. These vocabularies contain medical condition codes for family history as well as codes for relatives with a family history; however, there are no singular codes that link a medical condition code to a specific relative. Data from each healthcare organization's EHR are sent to a data repository at the Data Research Center for All of Us.

In this project, we identified family health history information in EHR data by reviewing the OMOP hierarchy for records with “family+history” or “FH:” anywhere in their OMOP concept name. We subsequently looked at parent concepts to identify any additional concepts that could be included. There were 235 unique OMOP concept names that satisfied these criteria (Supplementary Appendix 2). We excluded observations of “family social history” because family social history is related to a social situation like the death or absence of a family member and is not considered a medical condition. We also removed duplicate observation and value concepts from the same healthcare organization regarding the same participant. When searching for the hereditary diseases from a list of medically actionable genetic disorders as described previously, we manually reviewed all 235 OMOP concepts to identify codes that would specify these diseases (Supplementary Appendix 3). Additionally, we attempted to systematically link EHR family history information to specific diseases using the OMOP relations table, which maps EHR conditions or SNOMED concepts to family health history survey concepts (Supplementary Appendix 4). Each survey response is mapped to a SNOMED code using the “Maps to value” relationship; however, it is not identified as a family history code. Hence, we mapped the identified history concept to a set of history codes using the “Asso finding of” relationship. For instance, the “Daughter Cancer Condition: Lung Cancer” survey response has a “Maps to value” relationship with Malignant tumor of lung” which can be linked to “Family history of malignant neoplasm of lung” using the “Asso finding of” relationship. Using this approach of OMOP mapping, we mapped 9 of the 11 medically actionable genetic disorders to EHR family history conditions.

Statistical analysis

To compare family health history from surveys and EHRs, each survey question response or OMOP concept code was considered an observation. Each observation describes a positive or negative family history and may or may not have an associated relative or disease. A complete observation will ideally have a known family history of a specified disease for a certain relative. However, owing to the varying methods used by healthcare organizations when submitting OMOP mapped EHR data to All of Us, some information required for a complete family history may be missing. The structured nature of the family health history survey yields mostly complete observations, although the survey does not ask participants about negative family history of a specific disease. Therefore, all observations were assigned a category depending on the type of information present (Table 1). For example, there may be a positive family history or negative family history. The disease may be specified or not, meaning that the positive or negative family history is about a specific disease, such as breast cancer. Finally, a relative may be specified, such as family history in a mother. Either the disease or relative may not be specified leading to the categories in Table 1. To evaluate data types and information in the All of Us Research Program, we used descriptive statistics to (1) describe what kind of and how much information was present in the survey and EHR data, as categorized in Table 1; and (2) explore the presence of a family history of 11 diseases in the list adapted from American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics published recommendations. The descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages of categorical data (eg, number of observations with any family history data in surveys, EHRs, or both, and observations of family history of specific diseases, such as certain cancers, heart failure, myocardial infarction, or liver disease). Two authors (A.E.H., R.M.C.) reviewed data from 10 participants to explore the overlap between the survey and EHR data.

Table 1.

Classifications of family history based on the positive or negative family history, a specified disease, and a specified relative

| Class | Family History Classification | Survey Data | EHR Observation Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | |||

| 1 | Positive family history with a specified disease in specified relative | Responses to subquestions about relative conditions | Observation with relative + disease pair in a single row to confirm a match |

| 2 | Positive family history with a specified disease in unspecified relative | NA | EHR observations with family history disease concepts |

| 3 | Positive family history with an unspecified disease in specified relative | Responses of “Other,” “Other cancer,” or “Other/unknown diabetes” to the subquestions about relative conditions | Observations with family history relative concepts |

| 4 | Positive family history with an unspecified disease in unspecified relative | NA | Observations with “Family history of disorder” or ”Family history of clinical finding” concepts |

| Negative | |||

| 5 | Negative family history with a specified disease in specified relative | NA | NA |

| 6 | Negative family history with a specified disease in unspecified relative | NA | Observations with “No family history of disease” concepts |

| 7 | Negative family history with an unspecified disease in specified relative | Responses of “None of the above” at the relative condition parent-question level | Observations with “Relative alive and well” concepts |

| 8 | Negative family history with an unspecified disease in unspecified relative | NA | Observations with “No family history of” concepts |

| Other | |||

| 9 | Other | Responses of “Skip”/”Prefer not to answer”/”Don’t know”/”Not related by blood” at the relative condition parent-question level | EHR observations with “Family history with explicit context” |

EHR: electronic health record; NA: not applicable; UBR: underrepresented in biomedical research.

RESULTS

General findings

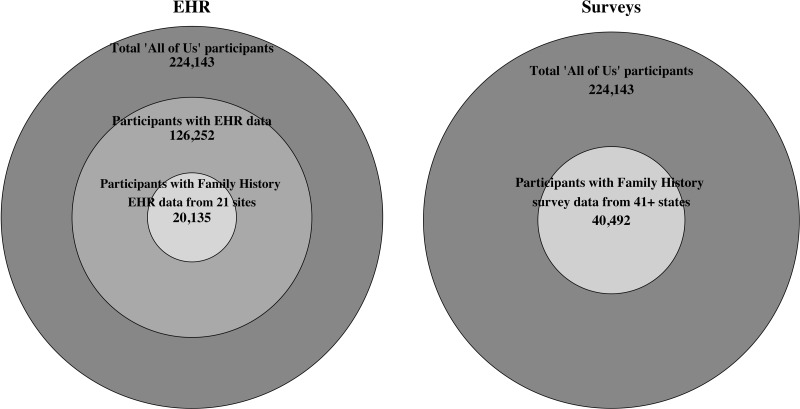

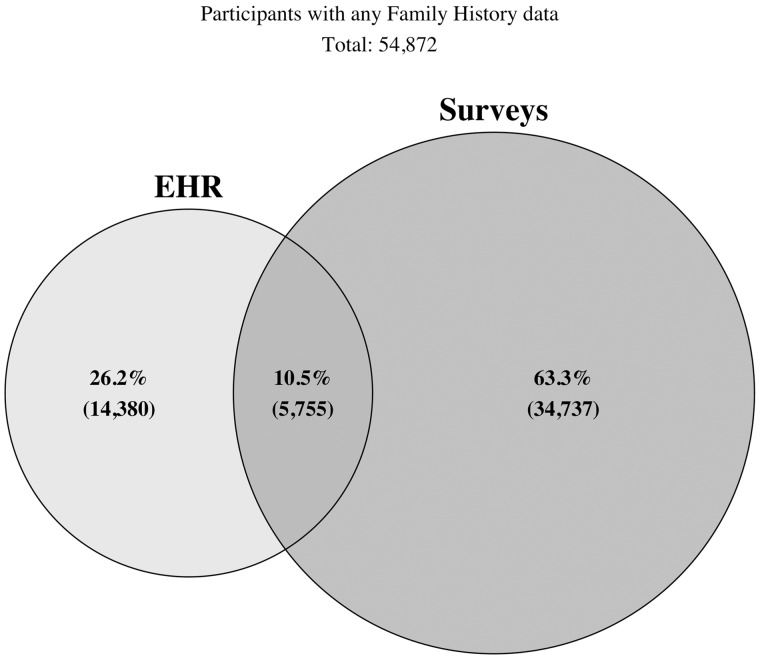

There were 224 143 participants in the registered tier version of the All of Us database. Of the total participants, any EHR observation data were available in 126 252 participants. Family history–related specific observations were available for 20 135 participants from 21 different healthcare organizations. The number of unique family history EHR observations per participant ranged from 1 to 16 (median of 1). Among the 224 143 All of Us participants who answered at least 1 question on any survey, 40 492 participants from more than 41 states completed the family health history survey (Figure 1). The number of conditions reported in survey responses ranged from 1 to 172 (median of 13). Using both data sources, there were 54 872 participants with 695 127 unique observations of any family history data. Of the total participants, 26% had family history observations from EHR only, 63% had survey observations only, and 11% had both survey and EHR observations (Figure 2). The percentage of family history data available stratified by participant-level variables including those classified as underrepresented in biomedical research, defined elsewhere (Supplementary Appendix 5),15 is represented in Table 2. The overall proportions of observations included in each family history category from Table 1 are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Number of participants in the All of Us cohort with family history data available from electronic health record (EHR) (left) and surveys (right). The largest circle describes the total number of participants in the cohort, the middle circle (left) describes participants having any EHR data, and the smallest circle describes the participants with family history EHR data (left) or survey family history data (right).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing the number of participants with electronic health record (EHR), survey, or overlap from both sources of any family history data out of the total number of participants with any family history data (N = 54 872).

Table 2.

Percentage of family health history information for participant-level variables including UBR as defined by the All Of Us Research Program

| Entire All of Us Cohort | Total EHR or Survey Participants | EHR-Only Participants | Survey-Only Participants | Overlap Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant-Level Variable | (n = 224 143) (%) | (n = 54 872) (%) | (n = 14 380) (%) | (n = 34 737) (%) | (n = 5755) (%) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 41 | 53 | 45 | 55 | 61 |

| Never married | 26 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 15 |

| Divorced | 14 | 13 | 17 | 11 | 12 |

| Living with partner | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| Widowed | 5 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 6 |

| Separated | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| No answer | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Health insurance status | |||||

| Yes | 91 | 97 | 95 | 97 | 98 |

| No | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Don’t know/No answer | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed/self-employed | 46 | 51 | 42 | 55 | 51 |

| Not employed | 51 | 48 | 56 | 44 | 48 |

| No answer | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| UBR category (UBR definition) | |||||

| Overall (met at least 1 UBR criterion) | 77 | 66 | 78 | 61 | 16 |

| Race/ethnicity (responses other than White or Hispanic/Latino) | 48 | 26 | 42 | 21 | 16 |

| Age ≥65 y | 26 | 35 | 37 | 33 | 43 |

| Sexual/gender minority | 13 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 8 |

| Sex at birth (not male or female) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gender identity | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| (neither man nor woman, or different than sex at birth) | |||||

| Sexual orientation | 12 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 7 |

| (responses other than straight) | |||||

| Income <$25 000 | 28 | 16 | 28 | 11 | 11 |

| Education (< GED) | 10 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

EHR: electronic health record; UBR: underrepresented in biomedical research.

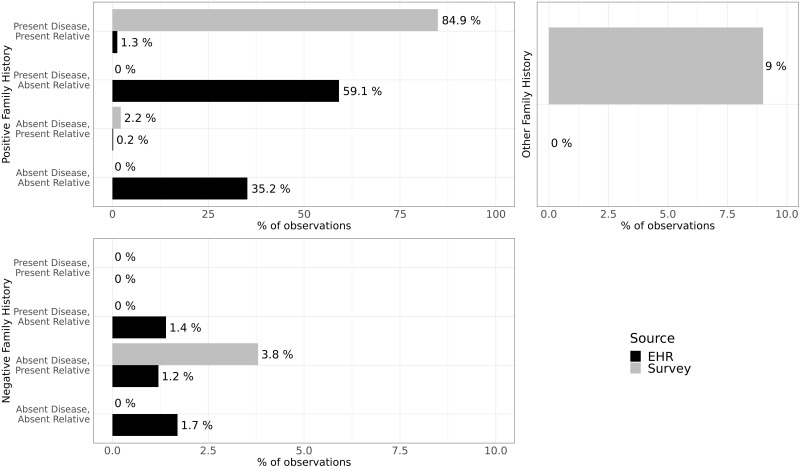

Figure 3.

Distribution of family history observations in survey and electronic health record (EHR) data stratified by positive or negative family history, presence or absence of disease, and presence or absence of a relative in the observation. The total number of survey observations was 658 034 and the total number of EHR observations was 35 997. Percentages of surveys and EHRs are based on the total numbers of observations, respectively.

Survey classifications

There were a total of 658 034 family health history survey data observations (this is the denominator for the percentages reported in this section). Positive family history of a specific disease made up 87.1% observations, 3.8% identified negative family history, and 9% comprised other responses.

Positive family history

Most observations had a positive history (presence) of a disease with a relative named (Table 1, class 1: 84.9%). Owing to the structured nature of the All of Us survey data, this is the most common classification (eg, a daughter with type 1 diabetes). A small number had only a relative named without a disease (class 3: 2.2%). Observations from this class were from survey questions that required free text responses (eg, daughter with other cancer, please specify). Owing to the complexity of mapping free text fields to OMOP as well as the All of Us privacy rules for the public dataset that remove all free text fields, we are unable to extract the presence of a specific disease from these responses.

Negative family history

A small percentage of observations had a negative (absent) family history of a disease with a named a relative (Table 1, class 7: 3.8%). In the survey, there is an option to select “none of the above” for all diseases in a specific relative (Supplementary Appendix 6). This is similar to responding that relative is alive and healthy.

Other

The “Other” category constituted answers submitted by participants that did not give a positive or negative family history. This 9% of observations which included the response options of “no siblings or children related by blood,” “don’t know,” or “prefer not to answer” (Supplementary Appendices 6 and 7).

EHR classifications

A total of 35 997 family history observations were from EHR data (this is the denominator for the percentages reported in this section). Positive family history made up 95.8% of the observations, 4.2% had negative family history data, and 20 or fewer observations were classified as “other.”

Positive family history

Only 1.3% (Table 1, class 1) of the family history EHR observations had both a relative and disease named. This was concluded via a row-level link in the OMOP observation table between a relative-specific family history code as an observation concept and a family history of disease code as a value concept. Most codes (59.3%) came from classes 2 and 3, indicating only a disease code or relative code without linkage. For example, sites will send a single observation disease and a separate observation for relative specification, without linking participant’s rows (Supplementary Appendix 8). In this example, a similar family history entry appeared on 2 separate dates (February 3, 2018, and February 20, 2018), and each date includes 2 codes. Of the 2 codes, one describes a family history of a disease (coronary arteriosclerosis) and the other identifies a relative (father). However, the disease and relative are not linked, so we cannot confirm that this combination refers to a father with coronary arteriosclerosis. There likely is a valid link in this case because there is only 1 disease and 1 relative present; however, linking multiple diseases and multiple relatives remains difficult. A smaller number of observations (class 4: 35.2%) identified the presence of family history, but without a disease or a relative. These concepts were “Family history of disorder” or “Family history of clinical finding.” While these data suggest that there is a family history of a condition, the specifics are unclear.

Negative family history

A small number of observations had a negative family history of a specified disease without a relative (Table 1, class 6: 1.4%). These cases included the concept code “no family history” of a disease (Supplementary Appendix 9). Very few observations had a negative family history of a relative without a disease (class 7: 1.2%). These concepts described family members that were alive and well (eg, “FH: Mother alive and well”). Finally, a negative history without a disease or relative was rarely observed (class 8: 1.7%). These were observations with a “No family history of” concept.

Other

Only 20 or fewer observations belonged to the other category, defined as having a concept of “Family history with explicit context” or “Other specified conditions influencing health status.” These codes are unclear if they signify a family history of a disorder.

Overlap between survey and EHR data

Of the 54 872 All of Us participants, 10.5% had overlapping family health history information from surveys and EHRs. To evaluate this overlap, we (1) conducted a closer examination of 10 random participants with overlapping family history observations (Supplementary Appendix 10), and (2) reviewed overlap of actionable medical disorders as presented in the next section. In all 10 cases, EHR and survey data were inconsistent, and each source provided more family health information than the other depending on the participant. Details about each participant are included in Supplementary Appendices 10 and 11.

Actionable medical disorders

There were 35 217 participants (86 054 observations) with a family history of diseases from the list of actionable medical disorders (Table 3). A family history of heart attack/myocardial infarction was the most reported (18 859 participants), followed by breast cancer (12 733 participants). All other diseases were reported by fewer than 10 000 participants. Breast cancer had the most overlap of survey and EHR data (6.2%), with all other diseases having 2% or less overlap (Table 3). EHRs contributed the most data in breast cancer (29.8% EHR only), followed by heart attack/myocardial infarction (8.7%), kidney cancer (5.7%), and colorectal cancer (3.2%). All other diseases had <1% of the information coming from EHR alone. Except for breast cancer, surveys contributed about 90% or more of the data, with congestive heart failure being almost exclusively seen in survey data.

Table 3.

Medically actionable genetic disorders from a list of genes and disorders for reporting secondary findings from genome sequencing

| Disease | Total EHR or Survey Participants (n = 54 872) | EHR-Only Participants (n = 14 380) | Survey-Only Participants (n = 34 737) | Overlap Participants (n = 5755) | Relative Ratio of Disease Discovery (EHR vs Survey) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | 12 733 | 3795 (29.8)a | 8144 (64.0)a | 794 (6.2)a | 1.033 |

| Lung cancer | 6753 | 28 (0.4) | 6705 (99.3) | 20 (0.3) | 0.014 |

| Colorectal cancer | 6171 | 198 (3.2) | 5893 (95.5) | 80 (1.3) | 0.094 |

| Stomach cancer | 2033 | 20 or fewerb | 1993 (98.0) | 20 or fewerb | 0.04 |

| Thyroid cancer | 1160 | 20 or fewerb | 1120 (96.6) | 20 or fewerb | 0.071 |

| Kidney cancer | 1191 | 68 (5.7) | 1103 (92.6) | 20 or fewerb | 0.158 |

| Brain cancer | 1955 | 20 or fewerb | 1915 (98.0) | 20 or fewerb | 0.042 |

| Liver disease | 2436 | 20 or fewerb | 2396 (98.3) | 20 or fewerb | 0.033 |

| Coronary artery disease | 9559 | 59 (0.6) | 9480 (99.2) | 20 or fewerb | 0.017 |

| Congestive heart failure | 9012 | 20 or fewerb | 8972 (100) | 20 or fewerb | 0.009 |

| Heart attack/myocardial infarction | 18 859 | 1649 (8.7) | 16 841 (89.3) | 369 (2.0) | 0.236 |

Values are n (%). The percentages for each row are calculated by the total participants in each row (eg, 3795 is 29.8% of 12 733). Relative ratio of disease discovery controls the unbalanced number of participants in the EHR and survey, and is defined as:

Which is equivalent to:

For breast cancer, this is = 1.033. A relative risk > 1 means that the EHR contains more disease information; a relative risk < 1 means that the survey contains more disease information.

EHR: electronic health record; UBR: underrepresented in biomedical research.

Distributions of data source contributions (EHR, survey, both) similar to the distribution of the entire cohort.

According to All of Us publication policy, all counts of participants in publications that are less than 20 should be generalized to the phrase “20 or fewer.”

DISCUSSION

This Demonstration Project describes and compares family health history data in surveys and EHRs mapped to OMOP from the All of Us Research Program. We discovered a large population of participants with data sourced from surveys or EHRs. There have been other registries with large populations of family health history, but they tend to focus on a specific disease or set of diseases and are usually from a single data source (eg, surveys or EHRs).16–18 Large genetic databases like the U.K. Biobank19 and Million Veterans Program20 collect multiple data sources including genetic information. A recent study from the UK Biobank demonstrated that self-reported family history can be limited without genetics.21 However, this UK Biobank study did not report on EHR data. Our demonstration project in All of Us works with a significant amount of data from both surveys and EHRs and provides an examination of diseases with effective interventions. However, like other studies,4–7,9,10 we discovered substantial gaps in data collected from the EHR and surveys. There are many important reasons for these gaps. Mapping of EHR data to a structured common data model (eg, OMOP) can lead to a loss of information because of an inability to obtain unstructured data from the EHR or difficulty transforming structured data to the common data model,22,23 such as error or omission of family history data due to participants forgetting information or not being aware of the information, or healthcare providers not obtaining or documenting the information. Finally, a lack of an ability to enter data, such as limiting the number of questions on a survey or what structured data can be entered on a specific EHR system, can cause these gaps. There were also interesting findings in the overlap of survey and EHR data. Despite limitations, our findings suggest that multiple data sources may provide more accurate family health history information than a single source alone.

Interesting insights surfaced from the examination of overlapping survey and EHR data. On the one hand, in many cases, more family history was available in the survey responses as compared with the EHR. The structured nature of the survey offers an opportunity for a more systematic collection of family history of specific diseases on relatives. On the other hand, diseases in EHRs were sometimes missing from the survey records. This discrepancy ultimately creates uncertainty in determining the gold standard for family health history information. In 1 case, a participant had responded that their father had a heart attack in the family health history survey (Supplementary Appendix 12), but their EHR noted that their father had coronary artery disease. Reasons for discrepancies between EHR and survey data could include (1) a chronological gap between when the participant answered the survey question and when the EHR data were entered (eg, a father may have had coronary artery disease at the time of the survey and later had a heart attack), (2) the ability of the participant to remember or understand the father’s disease, or (3) a data entry error by either the healthcare provider or the participant. Resolving these sources of discrepant information are areas for future research. Additional data sources can provide important complementary information. All of Us is collecting DNA for future genetic analyses. A comprehensive examination of the genome for pathogenic or likely pathogenic gene variants or polygenic risk scores in participants who report a family history may complement data from the patient surveys and EHR. Additionally, answers to questions such as “what percent of individuals reporting or not reporting family history of breast cancer have a mutation promoting breast cancer?” could be explored.

Medically actionable diseases also had discrepancies between the EHRs and surveys. History of breast cancer was present in more relatives in the EHR data than surveys because the family health history survey does not ask about distant relatives. Information about a participant’s family history of gastric cancer was present in the survey but not in the EHR, possibly owing to issues with specificity of what is in the EHR data or mapping of raw data to the OMOP format (eg, neoplasm of digestive organ). Therefore, ensuring that data in the EHR have the appropriate specificity of the disorder (eg, gastric cancer and not neoplasm of digestive organism) as well as improving mapping to OMOP can help. There was almost no overlap between surveys and EHR in the liver disease category (fewer than 20). The survey asks about a family history of liver disease, but again EHR data may not have been mapped to an OMOP concept like cirrhosis or liver disease because it is located in unstructured data or not typically captured. Generally, survey data had more extensive family history. In 1 participant’s family history of thyroid cancer, the EHR had only 1 mention of thyroid cancer for a specified relative, whereas the survey had 3 relatives with thyroid cancer. Owing to the lack of disease-relative linkage guidelines in the mapping of EHR data to OMOP, the surveys had more specific family history information. When considering certain mutations such as BRCA in analyzing the family history of breast cancer, more specific family history will be important.24 The finding that most medically actionable genetic disorders were in the surveys but not EHRs emphasizes the importance of properly capturing and mapping family history to common data models.

Data quality of family history within All of Us has important limitations and considerations. First, we do not have access to free text from the EHR or free text answers in the survey due to privacy rules in the registered tier to prevent reidentification of participants. Future directions to utilize natural language processing and map to OMOP could enable these data to be used. Second, limitations within EHR-specific family health history included a lack of linkage between diseases, relatives, and duplicates. Only a few sites sent linked OMOP codes between diseases and relatives. This could be related to the way the information is stored in their EHR or the lack of awareness that diseases and relatives could be transmitted to the data repository as a linked set. Improving the standard way in which these data are collected, transmitted, and stored for All of Us researchers could allow for more extensive analyses. Also, using a different standard like the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources could lead to different results. Third, the response rate of the family health history survey is low, and the All of Us Research Program is engaged in a campaign to increase completion rates of surveys from nonrespondents through phone calls and postal mailings. Response rates in surveys were particularly low in certain underrepresented in biomedical research populations such as lower education. Statistical weighting methods, such as inverse probability weighting, multiple imputation, or a combination of the 2, could be useful when trying to adjust for nonresponders.25 In addition, there may be other confounders limiting survey data, such as digital literacy, availability of stable Internet connections, or smartphones. These limitations should be considered by researchers using these data. Fourth, we assume that responses from surveys and EHR family history data are from blood relatives; however, participants may respond about adoptive relatives. Fifth, there were a significant number of duplicates in the EHR data. These duplicates may be true duplicates or could be additional family history. This distinction was difficult to determine given the limited row-level linkages between EHR diseases and relatives. True duplicates are potentially attributable to data being recorded in the EHR systems used to populate the OMOP instance at a 1-row-per-contact basis. Therefore, every time the participant completes a family history form or every time a provider reviews the family history data, another row could be populated in the EHR source data, and thus mapped into OMOP and sent to the data repository. Sixth, including a survey with all possible diseases and relatives may give more data but increases participant burden. Survey responses are also susceptible to misclassification and multiple biases. Last, these results are specific to the release of the registered tier in September 2019; future releases may include additional family history data (eg, additional OMOP codes) and data types not included in the current analysis.

The Demonstration Projects led by All of Us aims to describe the utility of family health history data available to researchers at the beta launch of the Researcher Workbench. All analyses shown here are available to registered users of the Researcher Workbench for replication and reuse to support hypothesis generation and discovery by the broader research community.

CONCLUSION

This description of the family health history data in the All of Us registered tier database will assist future investigators in understanding All of Us data methods and provide feedback to the program on the utility of participant surveys and EHR data. In this Demonstration Project, we demonstrated the potential informatics challenges and opportunities for biomedical research of family history data from different sources, which were mapped to a common data model in an attempt to identify a common source of truth regarding family history in a large, diverse cohort of participants across the United States.

FUNDING

The All of Us Research Program is supported (or funded) by grants through the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers (1 OT2 OD026549, 1 OT2 OD026554, 1 OT2 OD026557, 1 OT2 OD026556, 1 OT2 OD026550, 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553, 1 OT2 OD026548, 1 OT2 OD026551, 1 OT2 OD026555, IAA #: AOD 1603); Federally Qualified Health Centers (HHSN 263201600085U), Data and Research Center (5 U2C OD023196), Biobank (1 U24 OD023121), the Participant Center (U24 OD023176), Participant Technology Systems Center (1 U24 OD023163), Communications and Engagement (3 OT2 OD023205, 3 OT2 OD023206), and Community Partners (1 OT2 OD025277, 3 OT2 OD025315, 1 OT2 OD025337, 1 OT2 OD025276). In addition to the funded partners, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the contributions made by its participants. RMC was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL141447. JHK is supported by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (1OT2OD026549) and the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the NIH (K01HL143137).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RMC, RJC, CJO, AHR conceived the study design. All authors contributed to data collection. RMC, AEH, XF, QC performed data analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The Institutional Review Boards of the All of Us Research Program approved all study procedures and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

DATA SHARING

De-identified data are available on the researcher workbench of the All of Us Research Program located at https://workbench.researchallofus.org.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank the participants of the All of Us Research Program. We thank the countless other co-investigators and staff across all awardees and partners, without which All of Us would not have achieved our current goals. “Precision Medicine Initiative, PMI, All of Us, the All of Us logo, and The Future of Health Begins with You are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.”

The All of Us Research Program Demonstration Projects Subcommittee includes the following authors: Cheryl Clark; Elizabeth Cohn; Lucila Ohno-Machado; Mine Cicek; Eric Boerwinkle; Sheri Schully; Steve Mockrin; Kelly Gebo.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guttmacher AE, Collins FS, Carmona RH. The family history–more important than ever. N Engl J Med 2004; 351 (22): 2333–6. [Cros sRef][ 10.1056/NEJMsb042979] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haga SB, Orlando LA. The enduring importance of family health history in the era of genomic medicine and risk assessment. Per Med 2020; 17 (3): 229–39. doi: 10.2217/pme-2019-0091[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Donnell CJ. Family history, subclinical atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease risk: barriers and opportunities for the use of family history information in risk prediction and prevention. Circulation 2004; 110 (15): 2074–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bill R, Pakhomov S, Chen ES, Winden TJ, Carter EW, Melton GB. Automated extraction of family history information from clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2014; 2014: 1709–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Polubriaginof F, Tatonetti NP, Vawdrey DK. An assessment of family history information captured in an electronic health record. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2015; 2015: 2035–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ginsburg GS, Wu RR, Orlando LA. Family health history: underused for actionable risk assessment. Lancet 2019; 394 (10198): 596–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fiederling J, Shams AZ, Haug U. Validity of self-reported family history of cancer: a systematic literature review on selected cancers. Int J Cancer 2016; 139 (7): 1449–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kessels K, Eisinger JD, Letteboer TG, Offerhaus GJA, Siersema PD, Moons LMG. Sending family history questionnaires to patients before a colonoscopy improves genetic counseling for hereditary colorectal cancer. J Dig Dis 2017; 18 (6): 343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehrabi S, Wang Y, Ihrke D, Liu H. Exploring gaps of family history documentation in EHR for precision medicine -a case study of familial hypercholesterolemia ascertainment. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2016; 2016: 160–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murabito JM, Nam BH, D'Agostino RB Sr, Lloyd-Jones DM, O'Donnell CJ, Wilson PW. Accuracy of offspring reports of parental cardiovascular disease history: the Framingham Offspring Study. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140 (6): 434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Denny JC, Rutter JL, Goldstein DB, et al. The “All of Us” Research Program. N Engl J Med 2019; 381 (7): 668–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramirez AH, Sulieman L, Schleuter DJ, et al. The All of Us Research Program: data quality, utility, and diversity. medRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.29.20116905, 3 Jun 2020, preprint: not peer reviewed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cronin RM, Jerome RN, Mapes B, et al. Development of the initial surveys for the All of Us Research Program. Epidemiology 2019; 30 (4): 597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med 2013; 15 (7): 565–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mapes BM, Foster CS, Kusnoor SV, et al. Diversity and Inclusion for the All of Us Research Program: a scoping review. PLoS One 2020; 15 (7): e0234962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cannon-Albright LA, Carr SR, Akerley W. Population-based relative risks for lung cancer based on complete family history of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14 (7): 1184–91. = [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams RR, Hunt SC, Barlow GK, et al. Health family trees: a tool for finding and helping young family members of coronary and cancer prone pedigrees in Texas and Utah. Am J Public Health 1988; 78 (10): 1283–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams RR, Hunt SC, Heiss G, et al. Usefulness of cardiovascular family history data for population-based preventive medicine and medical research (the Health Family Tree Study and the NHLBI Family Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2001; 87 (2): 129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 2015; 12 (3): e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gaziano JM, Concato J, Brophy M, et al. Million Veteran Program: a mega-biobank to study genetic influences on health and disease. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 70: 214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel AP, Wang M, Fahed AC, et al. Association of rare pathogenic DNA variants for familial hypercholesterolemia, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and lynch syndrome with disease risk in adults according to family history. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3 (4): e203959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. FitzHenry F, Resnic FS, Robbins SL, et al. Creating a common data model for comparative effectiveness with the observational medical outcomes partnership. Appl Clin Inform 2015; 6 (3): 536–47. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2014-12-CR-0121[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klann JG, Joss MAH, Embree K, Murphy SN. Data model harmonization for the All Of Us Research Program: transforming i2b2 data into the OMOP common data model. PloS One 2019; 14 (2): e0212463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164 (4): 279–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Toscano JC, McMurray B. Cue integration with categories: Weighting acoustic cues in speech using unsupervised learning and distributional statistics. Cogn Sci 2010; 34 (3): 434–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.