Abstract

Background

Open notes invite patients and families to read ambulatory visit notes through the patient portal. Little is known about the extent to which they identify and speak up about perceived errors. Understanding the barriers to speaking up can inform quality improvements.

Objective

To describe patient and family attitudes, experiences, and barriers related to speaking up about perceived serious note errors.

Methods

Mixed method analysis of a 2016 electronic survey of patients and families at 2 northeast US academic medical centers. Participants had active patient portal accounts and at least 1 note available in the preceding 12 months.

Results

6913 adult patients (response rate 28%) and 3672 pediatric families (response rate 17%) completed the survey. In total, 8724/9392 (93%) agreed that reporting mistakes improves patient safety. Among 8648 participants who read a note, 1434 (17%) perceived ≥1 mistake. 627/1434 (44%) reported the mistake was serious and 342/627 (56%) contacted their provider. Participants who self-identified as Black or African American, Asian, “other,” or “multiple” race(s) (OR 0.50; 95% CI (0.26,0.97)) or those who reported poorer health (OR 0.58; 95% CI (0.37,0.90)) were each less likely to speak up than white or healthier respondents, respectively. The most common barriers to speaking up were not knowing how to report a mistake (61%) and avoiding perception as a “troublemaker” (34%). Qualitative analysis of 476 free-text suggestions revealed practical recommendations and proposed innovations for partnering with patients and families.

Conclusions

About half of patients and families who perceived a serious mistake in their notes reported it. Identified barriers demonstrate modifiable issues such as establishing clear mechanisms for reporting and more challenging issues such as creating a supportive culture. Respondents offered new ideas for engaging patients and families in improving note accuracy.

Keywords: patient safety, ambulatory care, health information technology, information transparency, speaking up

INTRODUCTION

Background

The patient-physician relationship is evolving to reflect a cultural shift in health information democracy and transparency. New federal regulation will vastly expand patient access to electronic data.1 Providing patients easy access to their health information can empower them to collaborate with physicians to make personalized health decisions.2 Greater transparency has driven patient-centered innovation, including easy access to visit notes (“open notes”) through the patient portal. More than 50 million patients in the US now have access to their notes and the practice is growing worldwide.3,4 Sharing visit notes with patients is a cultural change, since previously notes were routinely viewed by everyone but the patient: providers, insurers, regulators, and lawyers. Filled with medical terminology and abbreviations, notes were crafted by clinicians for clinicians, and not necessarily for patients, despite their legal right to their record.5 Today, however, electronic health records (EHRs) are increasingly being shared with patients and provide a meaningful opportunity for open communication and patient engagement.6

Sharing notes with patients can lead to benefits such as improved medication adherence and shared decision-making.7,8 It can also engage patients and their caregivers in safety-related behaviors such as test and referral follow-up.9,10 Alongside a growing literature that patients and families can find relevant errors and breakdowns in care,11–14 prior reports also demonstrate that patients and families can identify errors in their notes, the majority of which are clinically relevant.15 Partnering with patients to identify documentation errors may be particularly helpful in the ambulatory setting where errors are prone to occur in the “space between visits” and may not be as visible to providers.10

Significance

Prior studies of hospitalized and intensive care unit patients and families suggest that while some want to play an active role in their care, they do not always feel comfortable speaking up about perceived mistakes.16–18 Little is known, however, about barriers to speaking up in the ambulatory care setting, particularly when errors are identified in the electronic health record (EHR). In the era of transparency and expanded use of patient portals, patients and families will increasingly access their health information and may perceive mistakes.15,19 Understanding the barriers to speaking up about them may help target interventions to engage patients, improve EHR accuracy, and strengthen patient–provider safety partnerships.20

We surveyed patients and family members at 2 healthcare organizations about errors they found in their outpatient notes with the goals of determining:

How often patients and families who perceived a serious error in their notes notified their provider’s office about the error;

Barriers to, and factors associated with, speaking up about serious note errors; and

Patient and family recommendations for enabling speaking up about serious note errors.

METHODS

Survey development

An interdisciplinary team including patients and family members, healthcare delivery researchers, internal medicine and pediatric doctors and nurses, patient safety experts, health information technology representatives, and patient engagement leaders convened over the course of 1 year to develop the survey, which focused on the effect of reading visit notes on safety-related knowledge, behaviors, and engagement. The survey underwent external review by a survey scientist with expertise in patient and family engagement and cognitive testing with patients. Further details about its development are available elsewhere,7,10,21 and the survey is available upon request.

Survey items included multiple-choice and open-ended questions. Structured response categories included Likert scales, 0–10 scales, or Yes/No/Don’t know choices. This paper focuses on the results of questions regarding patient and family experiences with, and recommendations for, identifying and reporting serious errors in open notes. We defined “open notes” as “the notes written by your healthcare provider(s) about your health care visits that you can read online.” In the survey, we used the portal name of each respective study site and provided a screenshot of where notes are found on each patient portal. We asked patients who read at least 1 note: “Did you ever find a mistake in your notes (not counting misspellings, typing errors, or other trivial mistakes)?” We defined a “serious mistake” as “a problem that could have immediate effects on your care” and included examples, such as a wrong medication or incorrect list of medical problems. In contrast, we defined a “minor error” as “a problem that does not likely have immediate effects on your care” and included examples such as listing the wrong ages of family members. We defined reporting as “letting someone in your healthcare center know about the problem.” In this paper, we use the terms “reporting” and “speaking up” interchangeably, since letting someone in the healthcare center know about a perceived mistake requires speaking up about the concern and is likely influenced by factors known to affect patient comfort with speaking up.16,22

Participants

Adult patients at 1 northeast United States (US) academic hospital and adult portal account holders for pediatric patients at a second northeast US academic hospital were eligible to participate if they a) had logged onto the patient portal at least once and b) had at least 1 available open note, both within the year prior to the study period (June 2016–September 2016). The vast majority of portal accounts at the pediatric hospital belonged to parents or guardians. We excluded the small number of pediatric hospital patient respondents, such as adolescents, since they fell outside the target (adult) study population. Collectively, we refer to the study sample as “patients and families” for simplicity and consistency with previously published reports.10,23

At the adult hospital, we invited a random sample of half of the eligible patients to complete the survey through the patient portal, using a maximum of 2 reminders. The other half of the eligible adult patients were not contacted based on recruitment guidelines at our organization pertaining to eligibility for future studies related to open notes. At the pediatric hospital, we invited all eligible portal accounts, using a maximum of 3 reminders. We offered 10 raffle prizes (iPads) at each hospital as incentive for participation.

Analysis

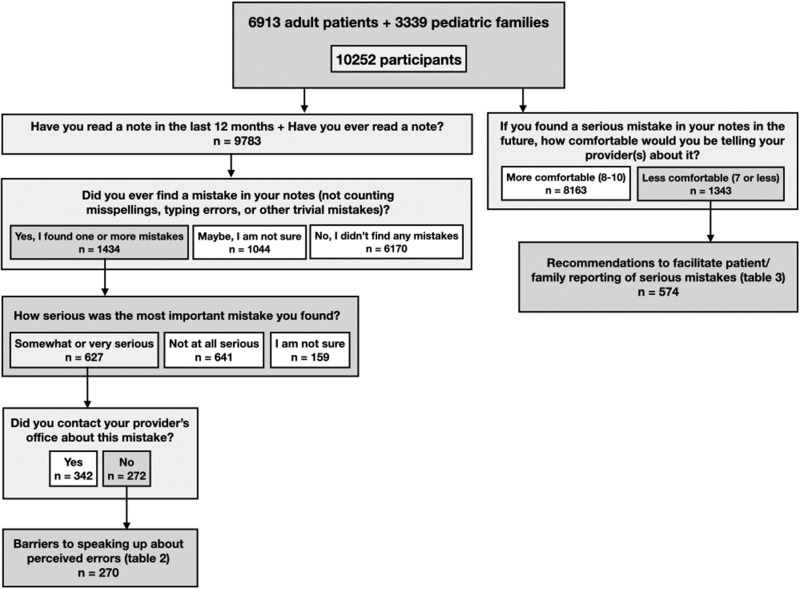

All participants were asked about agreement with general reporting attitudes such as, “Reporting mistakes improves patient safety.” We used SAS software version 9.4 and descriptive statistics to analyze attitudes about reporting, self-reported errors and notification of providers, and respondent characteristics; and the X2 test to compare responses between parents and family members. We employed 2 strategies to assess barriers to reporting. First, we evaluated barriers among participants who identified a perceived mistake in their notes but had not reported it. This allowed us to ground the data in actual experiences. Second, we solicited recommendations for how to facilitate reporting from any respondent who felt they would be uncomfortable reporting a serious mistake if they found 1 in the future. We chose this broader second strategy to understand what matters most to all participants who are not comfortable speaking up, since anyone may encounter a perceived serious mistake in their notes in the future (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing study population.

see him again—told all this to my PCP (of 30 years) whom I greatly trust… and got another

We first identified the proportion of respondents who perceived a serious mistake in their notes. For simplicity, we combined participant responses describing perceived errors as “somewhat serious” and “very serious” and refer to these as “serious.” Among those who identified a serious mistake we reported the proportion who notified their provider’s office about the mistake. Among those that did not notify their provider’s office, we calculated the frequencies of their reported barriers. Barriers were derived from the literature and respondents could select up to 3 that were most applicable. Participants who selected “other” were given space to describe the barrier. Two researchers (BL, SB) independently reviewed the “other” responses to batch responses that matched existing categories and categorized new barriers.

We used logistic regression to explore the relationship between patient and family demographics (including sex, race, ethnicity, education, and self-reported health) and 2 outcomes of interest: confidence finding mistakes in notes and likelihood of contacting the provider about a perceived serious mistake in their notes. In each regression model, we included participants for whom demographic information was available. Participants’ self-reported sex was identified for adult participants but was not available for family members of pediatric patients. Self-reported health reflected participant responses only (ie, adult patients and parents or guardians, the subjects of interest for speaking up). The survey used US Census categories for race and ethnicity, and patients were able to check off multiple races. Although there may be relevant differences between and within these heterogenous groups, participants who self-identified as Black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Pacific Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, other, and of multiple races, were grouped together to improve the power of this exploratory analysis. The intent of this analysis was not to draw generalized conclusions, but to raise awareness about potential inequities related to speaking up in order to guide further research.

Finally, we conducted a qualitative analysis of all patient narrative responses regarding recommendations to support speaking up about serious perceived mistakes. All survey respondents were asked how comfortable they would feel reporting a serious mistake in the future. Those who were less comfortable (responded ≤7 on a scale of 0–10) were asked, “Please tell us what would help you to report a serious mistake in your notes.” Two researchers (BL, SB) conducted a qualitative analysis of these free-text responses by first reviewing all respondent comments and independently creating a list of themes to reflect the data. The researchers then discussed the themes and iteratively developed a final codebook by consensus. The researchers used this codebook to independently code the free-text responses, assigning up to 3 codes per response. The researchers compared their coding assignments and reached consensus for every response.

Ethics

The study was approved by each site’s institutional review board (adult hospital protocol number 2016P000045 and pediatric hospital protocol number IRB-P0002184).

RESULTS

Participants

In total, 24 722 adult patients and 21 579 pediatric patient families were invited to take the survey; 6913 (28%) of adult patients and 3672 (17%) of pediatric patients and families completed the survey. Among pediatric patients and families, 3339 (91%) were parents or guardians (the “family” sample). In total, 10 252 participants comprised the patients and families study population.

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of the participants. Over 80% were white and had a college degree or higher, and compared to nonparticipants, participants at the adult hospital were more likely white, college-educated, and publicly insured.10 We were not able to compare participants and nonparticipants at the pediatric hospital because demographic information such as race, ethnicity, and education level was not routinely collected.10

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of the 10 252 patient and family participants

| Overall (n = 10 252)a | Patients (n = 6913)a | Family members (n = 3339)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex b | |||

| Female | N/A | 4343 (63%) | N/A |

| Male | N/A | 2570 (37%) | N/A |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 453 (5%) | 293 (4%) | 160 (5%) |

| Black or African American | 355 (4%) | 229 (4%) | 126 (5%) |

| White | 7792 (88%) | 5448 (89%) | 2344 (85%) |

| Other (including American Indian, Pacific Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander), and multiple races | 277 (3%) | 165 (2%) | 112 (4%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 391 (4%) | 224 (4%) | 167 (6%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 8506 (96%) | 5915 (96%) | 2591 (94%) |

| Education | |||

| High school graduate or less | 1395 (16%) | 1003 (16%) | 392 (14%) |

| Associates or bachelor’s | 3279 (37%) | 2168 (35%) | 1111 (40%) |

| Master’s or doctoral | 4310 (48%) | 3037 (49%) | 1273 (46%) |

| Employment | |||

| Employed for wages or self-employed | 6192 (69%) | 4053 (65%) | 2139 (77%) |

| Homemaker | 652 (7%) | 162 (3%) | 490 (18%) |

| Unemployed, retired, or unable to work | 2126 (23%) | 1985 (31%) | 141 (5%) |

| In general how would you rate your overall health? | |||

| Excellent | 1646 (18%) | 948 (15%) | 698 (25%) |

| Very good or good | 6443 (72%) | 4509 (72%) | 1934 (69%) |

| Fair or poor | 922 (10%) | 149 (6%) | 773 (13%) |

| How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself (in English)? | |||

| Not at all or a little bit | 79 (<1%) | 58 (<1%) | 21 (<1%) |

| Quite a bit or extremely | 8931 (99%) | 6171 (99%) | 2760 (99%) |

| How confident do you feel in your ability to find mistakes in your notes? | |||

| Not at all confident or a little confident | 477 (6%) | 323 (5%) | 134 (5%) |

|

Confident or very confident |

8534 (94%) | 5887 (95%) | 2647 (95%) |

N varies by item; total missing demographic information was <15% for any given item.

Participants’ self-reported sex was identified for adult participants but was not available for family members of pediatric patients.

Attitudes and experiences related to perceived mistakes in notes

Among respondents, 8724 (93%) believed that reporting mistakes improves patient safety, 8114 (86%) agreed they play an important role in preventing mistakes by reviewing information in the medical record, and 6896 (73%) thought that healthcare providers want to know about mistakes. In total, 8534 (94%) of respondents felt confident or very confident about finding mistakes in notes.

Of the 8648 participants who read at least 1 note and responded to the question, “Did you ever find a mistake in your notes,” 1434 (17%) identified 1 or more perceived mistakes in their notes, not counting misspellings, typing errors, or other trivial mistakes (an additional 1044 (12%) were “not sure”). Of those who identified a mistake, 627/1434 (44%) respondents felt the mistake was serious. Among these, 342/614 (56%) contacted their provider’s office about it, while 272/614 (44%) did not (13 individuals did not respond).

Barriers to speaking up about perceived serious mistakes in notes

Of the 272 respondents who perceived a serious mistake in their notes but did not contact their provider’s office, 270 (99%) reported barriers to speaking up (Table 2). The 3 most common barriers were: not knowing one could report a mistake (61%), not wanting to be perceived as a “troublemaker” (34%), and not knowing whom to call or talk to (27%). In addition, 23% of respondents didn’t speak up about the perceived mistake because they weren’t sure if it was important; 22% worried about annoying the provider, and 21% felt that nothing would be done about it.

Table 2.

Barriers to speaking up cited by participantsa who found a serious mistake in their notes but did not contact their provider’s office

| Reason | Overall n = 270 | Patient n = 194 | Family Member n = 76 |

|---|---|---|---|

| I didn’t know I could report a mistake | 164 (61%) | 113 (58%) | 51 (67%) |

| I don’t want to be thought of as “difficult” or a “troublemaker” | 92 (34%) | 65 (34%) | 27 (36%) |

| I didn’t know whom to call or talk to | 72 (27%) | 50 (26%) | 22 (29%) |

| I am not sure it’s important | 63 (23%) | 48 (25%) | 15 (20%) |

| I am worried I might make my provider annoyed | 58 (22%) | 39 (20%) | 19 (25%) |

| Nothing would be done about it | 56 (21%) | 42 (22%) | 14 (18%) |

| My provider(s) are too busy | 49 (18%) | 37 (19%) | 12 (16%) |

| I am too busy | 47 (17%) | 38 (20%) | 9 (12%) |

| I don’t want to get my provider(s) in trouble | 21 (8%) | 17 (9%) | 4 (5%) |

| I am afraid of seeming like I don’t understand medical words | 5 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Otherb | 69 (26%) | 52 (27%) | 17 (22%) |

participants could select up to 3 reasons; the total n is therefore greater than the number of respondents (n = 270). Data was missing for 2 participants.

Most responses in the “Other” category reflected participants’ plan to speak up later, such as at their next visit, and/or preferences to discuss the issue with their primary care doctor rather than a specialist.

Among “other” barriers, the majority planned to share information at a subsequent visit. Some respondents noted a preference for speaking to their primary care provider (PCP) while others switched providers entirely: “I’d already lost all confidence in this specialist—knew that I’d never [referral].”

Regression models: association between participant demographics and finding or reporting perceived serious mistakes

Among all responding participants with available demographic data (n = 6121), those who identified as female were more likely to report they were confident finding mistakes, compared to those who identified as male (OR 1.41; 95% CI [1.13, 1.76]). In contrast, participants who self-identified as Black or African American, Asian, other, or multiple race(s) (OR 0.48; 95% CI [0.36, 0.64]), those who had a high school education or less (OR 0.60; 95% CI [0.39, 0.92]), or those who reported poorer health (OR 0.65; 95% CI [0.49, 0.87]) were each less likely to report confidence in finding mistakes compared to their respective counterparts (Table 3A).

Table 3A. Model 1: Association between respondent demographicsa and feeling confident or very confident in finding mistakes in notes

| Odds Ratio Estimate (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.41 | (1.13, 1.76) | 0.003 |

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Race | |||

| Black or African American, Asian, other race (including American Indian or Pacific Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander), or multiple races | 0.48 | (0.36, 0.64) | <.0001 |

| White | 1.00 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.11 | (0.63, 1.95) | 0.73 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1.00 | ||

| Education | |||

| High school graduate or less | 0.60 | (0.39, 0.92) | 0.019 |

| Associate or bachelor’s | 0.68 | (0.54, 0.87) | 0.002 |

| Master’s or doctoral | 1.00 | ||

| Self-reported health | |||

| Fair or poor | 0.65 | (0.49, 0.87) | 0.004 |

| Good, very good, or excellent | 1.00 | ||

Each exploratory regression model included participants for whom demographic information was available.

Among the 627 respondents who reported finding a serious mistake, 442 had available demographic data. In our exploratory logistic regression analysis of this population, those who self-identified as Black or African American, Asian, other, or multiple race(s) (OR 0.50; 95% CI [0.26, 0.97]) or those who reported poorer health (OR 0.58; 95% CI [0.37, 0.90]) were each less likely to contact the provider compared to their counterparts (Table 3B). We did not observe a significant difference in likelihood to report the mistake to the provider by respondent sex, ethnicity, or education though the overall number of Hispanic or Latino patients who reported a perceived serious mistake was small, limiting the power of our analysis.

Table 3B. Model 2: Association between respondent demographicsa and contacting the provider’s office about a perceived serious mistake in notes

| Odds ratio estimate (OR) | 95% confidence interval (CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.92 | (0.58, 1.47) | .73 |

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Race | |||

| Black or African American, Asian, other race (including American Indian or Pacific Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander), or multiple races | 0.50 | (0.26, 0.97) | .04 |

| White | 1.00 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0.67 | (0.23, 1.94) | .46 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1.00 | ||

| Education | |||

| High school graduate or less | 1.10 | (0.34, 3.55) | .87 |

| Associates or Bachelors | 0.89 | (0.60, 1.33) | .57 |

| Masters or Doctoral | 1.00 | ||

| Self-reported health | |||

| Fair or poor | 0.58 | (0.37, 0.90) | .02 |

| Good, very good, or excellent | 1.00 | ||

Each exploratory regression model included participants for whom demographic information was available.

Patient and family recommendations

In total, 1343/9506 (14%) of participants reported they would feel less comfortable (≤7 on a 0–10 scale) reporting a serious mistake in the future. Among these, 574/1343 (43%) volunteered free-text recommendations about what would help them speak up. After excluding 98 comments that did not contain useful information (ie, “nothing” or “I don’t know”), qualitative analysis of the remaining 476 comments revealed 568 recommendations in 3 major categories: 65% of participants recommended clear instructions about how to report and whom to report to, 24% described cultural change needed to encourage reporting, and 17% suggested new ideas for patient–clinician collaboration on note accuracy (Table 4). A few noted seriousness of the error, education, and access to notes would affect speaking up.

Table 4.

Recommendations for overcoming barriers to speaking up by patients and families who feel less comfortable reporting serious mistakes

| Theme | n a | Suggestions | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructions for how to report and whom to report to | 311/476 (65%) |

|

“Make it easy to quickly do online…” “To make a phone call during the day when my doctor is available or the office is open is very challenging. Being able to communicate by e-mail would be very helpful.” “A confidential discussion with another medical provider…” “Who would be the best person to tell? Doctors are very busy and if we were to call the office it is unlikely to be done.” “It would take 4 phone calls to fix, there is no easy way to get anything done over there. It involves phone call after phone call to actually get your point across.” |

| Cultural change to encourage reporting | 114/476 (24%) |

|

“Knowing there would be no retribution…with my child’s care.” “Ease of reporting and reinforcing just working together as a team for accuracy.” “Knowing if I pointed out the mistakes they would be corrected. Not with an addendum but literally corrected.” “…Make sure [the] provider won’t get in trouble.” “Feeling like providers want to hear from parents.” |

| Proposed innovations for reporting EHR mistakes | 79/476 (17%) |

|

“…if patients could add their own notes, which could include things like points the patient forgot to make in the appointment.” “Having a checkbox after each note on [the patient portal] that would allow the patient to 1) document that they’d seen the note, and 2) verify that their personal history, family history, and current medical issue and/or reason for visit were accurately noted.” “Notes [could] be thought of as ‘drafts’ pending patient review.” “It would help to have some templates online so that I could choose how [to] write about the mistake. I don’t want to offend my doctor and I’m afraid to use [the] wrong words.” “Make the note clickable and possible to type a correction into it. Then the correction could go to the doctor and she could look at it and click “accept” or “reject,” and she could either delete her own mistake or keep alongside my correction (maybe in another color font).” |

| Seriousness of perceived mistake | 32/476 (7%) |

|

“I’m not sure I would call unless it affected my immediate health.” “If there were serious consequences, such as [a] recommendation for a condition I don’t have.” |

| Education on medical concepts, errors, and importance of reporting | 20/476 (4%) |

|

“I don’t know the consequence of having the note corrected/not corrected.” “I am not sure why Open Notes is important for me to keep accurate, so an explanation of that would help me report a serious mistake.” “The notes are filled with acronyms, making it hard to fully understand the doctor’s degree of concern about the issue that included the mistake.” |

| Access to notes | 12/476 (3%) |

|

“Having all providers’ notes be eligible for feedback.” “Immediate access to [the] note while the visit [is] still fresh in my memory.” |

476 patient comments included a total of 568 recommendations.

A majority of respondents (65%) discussed reporting mechanisms including clear instructions about how to report a mistake and whom to report the mistake to. Most participants wanted to report mistakes online using a fast and easy instrument and many preferred an objective third-party reviewer other than their own doctor. In addition to the convenience of online reporting, some respondents noted that asynchronous reporting was less anxiety-provoking:

“Phone calls and e-mail to doctors tend to make me anxious and I therefore tend to avoid them. I may report it if there was an automated form with a way to select the error in the note, write in the correction, and then submit it for approval.”

Others expressed frustration at the lengthy process for trying to report errors. Several participants commented on respectful and timely communication:

“Have nicer people answering the phone at the office. Don’t be put on hold forever just to be rudely told ‘they will send an e-mail to the doctor.’”

About one-quarter (24%) highlighted the need for cultural change such as assurance against retribution for patients, families, and clinicians. They emphasized the importance of helping patients and families feel more comfortable discussing mistakes, especially with specialists and other clinicians with whom they do not have a longstanding relationship. Participants also underscored the importance of clinician encouragement:

“It would be nice if…the provider said if there is a mistake in any reports, please contact the office to have it corrected. This would eliminate the feeling of bothering the provider.”

Several suggested prompting patients with specific language:

“If you see any incorrect information of these categories (describe, ‘serious, important, not serious’) we ask that you do this/do that/press this button/write this down immediately, or present it to your provider on your next visit…”

In addition, several respondents cited the importance of responding meaningfully to patient reports:

“The reason for not reporting this time was that it was not corrected last time, and I was told ‘It’s fine the way it is.’”

Nearly 1 in 5 (17%) proposed innovations for reporting and fixing perceived EHR mistakes. Many suggested a method for patients to approve or edit notes through the patient portal, even considering clinician notes as a “draft, pending patient review.” Participants also described a “button” or “checkbox” indicating patient/family approval of a note and “a way to highlight the mistake online and submit a proposed correction.” Some suggested templated language for corrections to ease patient discomfort about how to address the issue. Others recommended the ability to enter a “self-note” or ask that requested changes be recorded even if the changes are not made. Participants sought more effective ways to correct mistakes than currently used, pointing out that addenda at the end of notes are not adequate:

“After a month and multiple e-mail and phone calls, she put an amendment on the bottom of the note. This really didn't solve the problem because anyone who read the note would have to read the entire incorrect note to see the amendment at the bottom, and the errors were still there. When I called Patient Relations…I was told that my only recourse was a long process in which I would have to download, print, fill out, and mail in a form, and then there would be a review board, and it would take months. I was also told that there is no way for a provider to actually make changes in their notes, they can only add. This is a ludicrous system, I shouldn't have to go through a ton of work to correct a mistake someone else made, and it is [the 21st century], everything should be available online.”

Fourteen percent of responses indicated that the seriousness of the perceived mistake, the availability of records in general, and education to enhance patients’ understanding of the purpose of reporting errors would influence speaking up. For example:

“I would call if it was a wrong prescription…but if it was my weight listed wrong, I would be fine e-mailing or talking about it at my next visit.”

Another patient commented:

“If [notes are] just for patients, as long as you know your doctors are on top of it even if they wrote the wrong thing, I probably wouldn’t report it. But if the healthcare professionals use [the notes] and it might affect my future case, then I’d want to report it somehow.”

DISCUSSION

In our study of over 10 000 patients and families, roughly 1 in 5 respondents reported finding a mistake in visit notes and considered 40% of these to be serious. These findings reinforce prior similar results,19 now including new study populations (ie, families of pediatric patients) and further adding to the field by examining barriers to speaking up and patient and family recommendations. More than 75% of respondents believed healthcare providers want to know about patient-identified mistakes. Yet among those who perceived a serious mistake, only about half reported the mistake to their provider’s office.

The most common barriers to reporting included actionable issues such as how to report and more challenging cultural issues, such as fear of retribution. Patient and family recommendations tracked closely with reported barriers. The most commonly cited barrier (not knowing one could report) and the most common recommendation (clear online reporting instructions) were each cited by more than 60% of participants. As health information transparency spreads and more patients have access to their EHRs,24 patients and families will likely identify documentation errors and organizations will need systems to support and receive patient feedback.19,25

One of the barriers to speaking up cited in this study was the lack of meaningful response, consistent with prior reports.10,26 In an age where physicians are charting during off hours and burnout rates are high,27 thoughtful approaches that limit additional responsibilities for physicians are needed. Patients themselves were concerned that physicians are too busy to address errors. At the same time, many emphasized the known importance of provider encouragement to speak up.20,28 They also underscored the limitations of “addenda” because the mistake is preserved in the original note and may be propagated in future notes; a concern shared by some clinicians who may then miss important changes to the record.

Respondents revealed a preference for discussing errors with their PCP, even if that was not the person who made the error—a factor that may be uniquely important in the ambulatory setting. Some patients considered it less important to speak up about perceived errors in one-time settings with specialists, and a few reported that a mistake drove them to switch providers, a proactive choice that may not be available in inpatient settings. These findings highlight the challenge to encourage reporting when a patient is seeing a provider they do not know well. It also raises implications for better supporting PCPs to respond to patient-perceived errors involving another provider and to provide feedback to colleagues when necessary—both known to be challenging tasks.29 In some cases, an objective “third person” to triage and respond to error reports may help, and, interestingly, was often suggested by respondents in our study.

Respondents reported that perceived error seriousness influences when and how they speak up and suggested providing education about how to identify errors and why reporting errors is important. This recommendation speaks to over 1000 patients and families in this study who were not sure if they identified a mistake in their notes, multiple sociodemographic groups who were less likely to report confidence finding mistakes, and those who perceived a mistake but were not sure about its seriousness. With educational support, patient self-triage of perceived errors may help organizations to respond meaningfully.19

As experts urge patients and families to engage in safety,30 patients—informed by their other online experiences—already envision ways they can engage with the EHR. Respondents asked for new technical capabilities such as templates, checkboxes, and other systematic online solutions that may not only improve individual EHRs, but also facilitate organizational learning through aggregation of patient reports.31 Templates for reporting mistakes could ease the psychological burden for patients and families by reinforcing the acceptability of reporting errors, outlining common types of mistakes, and normalizing reporting language. Other respondents entirely reimagined the role of the patient in medical documentation, asking that notes be sent to patients for approval before publication, that patients be allowed to add their own notes to the EHR, and that patients review and correct their own medical, family, and surgical histories on the portal. A few of these suggestions are in active testing with positive early findings.15,23,32,33 Although such changes raise concerns for some clinicians and healthcare leaders, the future of health information transparency in the context of the recent 21st Century Cures Act will rely on including patients and families meaningfully.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has also created an environment ripe for innovation34–37 that may pave the way to developing stronger partnerships with patients and families.

Our exploratory analysis of sociodemographic factors associated with speaking up suggests that some of the inequities underscored by the pandemic may extend to patient confidence in finding errors in notes and comfort reporting them, though further research is needed. Prior research has shown that vulnerable populations are less likely to be offered access to patient portals,38,39 demonstrating how new technologies can exacerbate existing inequities. Any future innovations related to speaking up may require not only patient-centered technological and educational interventions but also policy-level changes to address healthcare’s structural inequities.40

There are several limitations to this study. The response rate was low, although not dissimilar from other online surveys.41,42 While this is among the largest studies of its kind, engaging patients and families about barriers and recommendations for speaking up about perceived note errors, a relatively small proportion of the participants reported a perceived error and could therefore comment directly on the experience. The majority of respondents were white, employed, and well-educated; preliminary findings related to race and ethnicity should be viewed as exploratory. There may be important within-group differences among the populations grouped in our study due to small sample size, and larger studies of more diverse patients are needed. Other factors such as age, mental health, preferred language, and health literacy should also be examined.22 The study was also limited to patients who access their online portals, since this was a prerequisite to reading open notes. Several barriers may restrict portal use for more vulnerable patients.43,44 Finally, the severity of perceived mistakes was judged by participants and not verified by chart review or clinician assessment, as this was beyond the scope of this study. While prior studies demonstrate clinical relevance of patient-reported errors,13,14,16,45 future research should characterize what kinds of mistakes patients and families are willing to speak up about, alignment of those issues with clinician priorities, and the ultimate impact on patient outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Among patients and families who read visit notes and identified a perceived serious error, nearly half did not report the error. The most common barriers—not knowing patients could report and how to report—may be readily actionable. Others, such as improving reporting culture, will require greater and sustained efforts to create environments that support all patients, especially more vulnerable groups, to speak up. Respondents strongly preferred online, asynchronous communication for reporting with a timely response, in the setting of clinician encouragement and safety education. About a fifth of participants recommended new reporting tools that do not yet exist, suggesting a ripe environment for innovation and patient partnership at a time when such engagement is prioritized.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a grant from CRICO/Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the concept, design, and drafting of the study. SKB and FB designed the survey and collected data; BDL, SKB, and ZJD analyzed the data; BDL, ZJD, FB, and SKB critically reviewed the data, manuscript, and gave final approval.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jan Walker, RN, MBA and Suzanne Leveille, PhD, RN for their assistance with survey development; Alan Fossa, MPH for analytic support; Daniele Ölveczky, MD, MS, Interim Director for the Center for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for her thoughtful guidance on describing results from the exploratory analysis involving race and ethnicity; and the Patient and Family Advisors at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for their valuable contributions to the OpenNotes Patient Safety Initiative. The authors also thank the patients and families who shared their experiences and insights on the survey.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ONC's Cures Act Final Rule. 2020. https://www.healthit.gov/curesrule/ Accessed March 18, 2020.

- 2. Sands DZ, Wald JS. Transforming health care delivery through consumer engagement, health data transparency, and patient-generated health information. Yearb Med Inform 2014; 9: 170–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. OpenNotes. 2020. www.opennotes.org Accessed September 5, 2020.

- 4. Salmi L, Brudnicki S, Isono M, et al. Six countries, six individuals: resourceful patients navigating medical records in Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Sweden, and the USA. BMJ Open 2020; 10 (9): e037016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Employee Benefits Security Administration. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Washington, DC: US Department of Labor; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walker J, Darer JD, Elmore JG, et al. The road toward fully transparent medical records. N Engl J Med 2014; 370 (1): 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fossa AJ, Bell SK, DesRoches C. OpenNotes and shared decision making: a growing practice in clinical transparency and how it can support patient-centered care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 25 (9): 1153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DesRoches CM, Delbanco T, Bell SK. Patients managing medications and reading their visit notes. Ann Intern Med 2019; 171 (10): 774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chimowitz H, Gerard M, Fossa A, et al. Empowering informal caregivers with health information: OpenNotes as a safety strategy. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2018; 44 (3): 130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bell SK, Folcarelli P, Fossa A, et al. Tackling ambulatory safety risks through patient engagement: What 10,000 patients and families say about safety-related knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes after reading visit notes. J Patient Saf 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Etchegaray JM, Ottosen MJ, Aigbe A, et al. Patients as partners in learning from unexpected events. Health Serv Res 2016; 51 (Suppl 3): 2600–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Weingart SN, et al. Comparing patient-reported hospital adverse events with medical record review: do patients know something that hospitals do not? Ann Intern Med 2008; 149 (2): 100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khan A, Furtak SL, Melvin P, et al. Parent-reported errors and adverse events in hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170 (4): e154608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khan A, Coffey M, Litterer KP, and the Patient and Family Centered I-PASS Study Group, et al. Families as partners in hospital error and adverse event surveillance. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171 (4): 372–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bell SK, Gerard M, Fossa A, et al. A patient feedback reporting tool for OpenNotes: implications for patient–clinician safety and quality partnerships. BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 26 (4): 312–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bell SK, Roche SD, Mueller A, et al. Speaking up about care concerns in the ICU: patient and family experiences, attitudes and perceived barriers. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27 (11): 928–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KAS, et al. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled ‘difficult’ among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012; 31 (5): 1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fisher KA, Gallagher TH, Smith KM, et al. Communicating with patients about breakdowns in care: a national randomised vignette-based survey. BMJ Qual Saf 2020; 29 (4): 313–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bell SK, Delbanco T, Elmore JG, et al. Frequency and types of patient-reported errors in electronic health record ambulatory care notes. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3 (6): e205867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Entwistle VA, McCaughan D, Watt IS, et al. ; PIPS (Patient Involvement in Patient Safety) group. Speaking up about safety concerns: multi-setting qualitative study of patients' views and experiences. Qual Saf Health Care 2010; 19 (6): e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gerard M, Chimowitz H, Fossa A, et al. The importance of visit notes on patient portals for engaging less educated or nonwhite patients: survey study. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20 (5): e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fisher KA, Smith KM, Gallagher TH, et al. We want to know: patient comfort speaking up about breakdowns in care and patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf 2019; 28 (3): 190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bourgeois FC, Fossa A, Gerard M, et al. A patient and family reporting system for perceived ambulatory note mistakes: experience at 3 U.S. healthcare centers. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019; 26 (12): 1566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: A state of the science review. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17 (6): e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Muñana C, Kirzinger A, Brodie M. Data Note: Public's Experiences with Electronic Health Records. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019. https://www.kff.org/other/poll-finding/data-note-publics-experiences-with-electronic-health-records/ Accessed September 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30 (15): 1784–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Melnick ER, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky CA, et al. The association between perceived electronic health record usability and professional burnout among US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2020; 95 (3): 476–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davis RE, Jacklin R, Sevdalis N, et al. Patient involvement in patient safety: what factors influence patient participation and engagement? Health Expect 2007; 10 (3): 259–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallagher TH, Mello MM, Levinson W, et al. Talking with patients about other clinicians’ errors. N Engl J Med 2013; 369 (18): 1752–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Patient Safety Foundation. Safety is Personal: Partnering with Patients and Families for the Safest Care. Boston, MA: National Patient Safety Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gillespie A, Reader TW. Patient-centered insights: Using health care complaints to reveal hot spots and blind spots in quality and safety. Milbank Q 2018; 96 (3): 530–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mafi JN, Gerard M, Chimowitz H, et al. Patients contributing to their doctors’ notes: Insights from expert interviews. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168 (4): 302–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kriegel G, et al. Covid-19 as innovation accelerator: cogenerating telemedicine visit notes with patients. NEJM Catalyst. Published online May 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hollander J, Sites F. The transition from reimagining to recreating health care is now. NEJM Catalyst 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/cat.20.0093 Accessed September 5, 2020.

- 35. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382 (18): 1679–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Judson TJ, Odisho AY, Neinstein AB, et al. Rapid design and implementation of an integrated patient self-triage and self-scheduling tool for COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (6): 860–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Annis T, Pleasants S, Hultman G, et al. Rapid implementation of a COVID-19 remote patient monitoring program. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (8): 1326–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wallace LS, Angier H, Huguet N, et al. Patterns of electronic portal use among vulnerable patients in a nationwide practice-based research network: from the OCHIN Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN). J Am Board Fam 2016; 29 (5): 592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clarke MA, Lyden ER, Ma J, et al. Sociodemographic differences and factors affecting patient portal utilization. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2020. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs40615-020-00846-z Accessed September 5, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Antonio MG, Petrovskaya O, Lau F. Is research on patient portals attuned to health equity? A scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019; 26 (8–9): 871–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Forcino RC, Barr PJ, O'Malley AJ, et al. Using CollaboRATE, a brief patient-reported measure of shared decision making: Results from three clinical settings in the United States. Health Expect 2018; 21 (1): 82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medicaid. Methodology Report: 2014-2015 Nationwide CAHPS Survey of Adults Enrolled in Medicaid between October and December, 2013.https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/performance-measurement/methodology-report.pdf Accessed September 5, 2020.

- 43. Goel MS, Brown TL, Williams A, et al. Disparities in enrollment and use of an electronic patient portal. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26 (10): 1112–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gordon NP, Hornbrook MC. Differences in access to and preferences for using patient portals and other eHealth technologies based on race, ethnicity, and age: a database and survey study of seniors in a large health plan. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18 (3): e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Herlihy M, Harcourt K, Fossa A, et al. An opportunity to engage obstetrics and gynecology patients through shared visit notes. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 134 (1): 128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.