Abstract

PURPOSE: We hypothesized that a difference in restricted diffusion would exist in patients with connective tissue disorders (CTD) as compared with those without CTD. Our purpose was to determine whether the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) measurement could be used to identify parotid abnormalities in patients with CTD.

METHODS: One neuroradiologist, who was unaware of patient histories, retrospectively measured the ADC values for the parotid glands in 121 patients who underwent clinically indicated brain MR imaging in which the parotid glands were sufficiently depicted. Regions of interest were obtained from both the left and right parotid glands. After the medical records were reviewed and exclusion criteria were used, 90 non-CTD and seven CTD patients (systemic lupus erythematosus = 5; discoid lupus erythematosus = 1; Sjögren syndrome = 1) remained. The two groups were then compared. Statistical analysis consisted of Wilcoxon sign rank and Mann-Whitney tests.

RESULTS: The combined mean ADC for both parotid glands in 90 healthy patients was 0.50 ± 0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.44 × 10−3, 0.56 × 10−3). The combined mean ADC for both parotid glands in the seven CTD patients was 0.96 ± 0.24 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.79 × 10−3, 1.14 × 10−3). The mean ADC for the CTD patients’ parotid glands was significantly higher than that of the non-CTD patients (P = .0001), which suggests there is less restricted diffusion in parotid glands affected by CTD when compared with normal parotid glands.

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that ADCs may be used to detect parotid abnormalities in patients with CTD that are not identified by standard imaging. Although preliminary, the results indicate a potential role for ADC mapping in detection of subclinical parotid disease.

The salivary glands, as an organ system, have one of the greatest diversities of pathology, ranging from infection and inflammation to various neoplasms (1–17). Currently, an assessment of the parotid gland can be performed with biopsy, fine needle aspiration, sialography, ultrasonography, CT, scintigraphy, and various MR imaging techniques (7, 10, 18–25). Each diagnostic technique varies in invasiveness, degree of soft tissue differentiation, and spatial resolution (10). Some imaging techniques are more appropriate for tissue assessment, whereas others are more useful for ductal evaluation (7, 18, 19).

For diffuse parotid gland disorders, such as systemic connective tissue disorders (CTD), tissue sampling through biopsy is the criterion standard, but it is highly invasive, operator dependent, and can characterize only the portion of the gland from where the sample was obtained (26). Ultrasonography, CT, and MR imaging are used routinely to assess the degree of salivary gland involvement in CTD (10, 21). Enlargement of the parotid gland in CTD patients is shown by CT in 25–55% of the cases (25). Standard T1- and T2-weighted MR imaging appears to confer additional parenchymal definition that may be useful in evaluating the degree of salivary gland involvement in patients with CTD, particularly patients with Sjögren syndrome (27); however, these abnormalities are often identified in advanced stages of the disease (27).

Diffusion-weighted imaging has been shown in the central nervous system to identify certain pathologic conditions, such as ischemia, earlier than standard T1- and T2-weighted MR imaging (28). Potentially, diffusion-weighted imaging could similarly reveal early pathologic abnormality in the salivary glands. Diffusion-weighted imaging with apparent diffusion coefficients (ADCs) has the advantage of determining whether increased diffusion-weighted signal intensity is due to restricted diffusion or T2-weighted shine-through (29). Although ADC values have been used in the central nervous system, little is known about ADC mapping in the head and neck structures outside of the central nervous system (30, 31). Recent studies have shown that diffusion-weighted imaging with ADC mapping can be used to characterize lesions in a variety of head and neck disorders (30, 32). The purpose of our study is twofold: 1) to quantitate the normal ADC values of the parotid parenchyma and 2) to compare the ADC values of the normal parotid gland with patients with CTD.

Methods

Patient Selection

Individuals in whom clinically indicated brain MR imaging had been obtained between May 2001 and September 2001 were considered for the retrospective study. To be included, the MR imaging examination must have depicted both parotid glands on axial 2D spin-echo T1-weighted and diffusion-weighted images, as determined by visual inspection of the MR imaging images. A total of 121 individuals (46 men and 75 women; 1–85 years of age [mean, 39 years]) fulfilled inclusion criteria. Because this was a retrospective review, this study was deemed exempt from continuing review by our institutional review board.

The clinical indications for the MR imaging study in these patients included psychiatric disorders (n = 2); evaluation of mass lesions, benign and malignant (n = 46); neurologic disorders, including headache, seizure, dementia, multiple sclerosis, Menière disease, Grave disease, diplopia, vertigo, neuropathy, ataxia, dystonic posturing, tremor, hemiparesis, syncope, blurred vision, aphasia, and anosmia (n = 52); hemorrhage (n = 1); infarct (n = 6); closed head injury (n = 3); anatomic disorders (n = 5); evaluation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE; n = 4); and parotid disorders (n = 2).

We excluded patients who were younger than 5 years (n = 6), had known parotid lesions, surgery, or trauma (n = 2), or had a history of radiation therapy (n = 16). A total of 97 patients (36 men and 61 women; 5–85 years of age [average, 42 years]) formed the study population (seven patients with known connective tissue disorder (CTD) [five with SLE, one with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and one with Sjögren syndrome]; 90 without known CTD). Neither the patients with CTD nor the controls had documented complaints of salivary dysfunction. Fulfillment of the final exclusion criteria and segregation based on the presence or absence of CTD was determined by electronic records review of all available clinical data.

MR Imaging Technique and Analysis

All examinations were performed by using a 1.5-T system (Signa; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) with a standard head coil (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). The parameters for the axial 2D spin-echo T1-weighted sequence were a TR/TE of 500/14, a 6.0-mm section thickness with 0–2-mm interslice gap, a 22 × 22-cm field of view, and a 128 × 128 matrix. The parameters for diffusion-weighted images were a minimum TE of 74.9 ms, a TR of 10,000 ms, and b = 1,000 s/mm2. ADC maps were generated by using a pixel-by-pixel calculation as referenced by Wang et al (30).

After confirmation of parotid gland location on diffusion-weighted images (Figs 1 and 2), ADC maps were generated by a single observer (R.R.P.) from the axial diffusion-weighted images (Figs 1 and 2). Regions of interest, measuring approximately 74 mm2, were manually defined in a relatively homogeneous area in each parotid gland. If no area was deemed homogeneous, an area that was most representative of the parotid gland was selected. ADC was recorded for each defined region of interest. As an internal control, the ADC in a 31-mm2 region of interest defined in the center of the spinal cord at the level of the parotid glands was recorded in all seven patients with CTD and in 54 representative non-CTD patients. Spinal cord measurements in the upper area of the neck were consistent with the measurements made by in the reference study by Wang et al (30).

Fig 1.

Images obtained in 23-year-old female patient evaluated for headache.

A, T1-weighted axial MR image through the parotid gland (P). Arrow, spinal cord; arrowheads, mandibular rami.

B, Diffusion-weighted MR image through the same level demonstrating manually defined regions of interest over the parotid gland (P) and spinal cord (arrow).

C, ADC map with manually defined regions of interest over the parotid gland (P) and spinal cord (arrow).

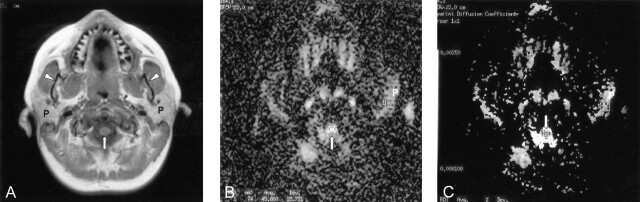

Fig 2.

Images obtained in a 47-year-old female patient with SLE referred for mental status changes.

A, T1-weighted axial MR image through the parotid gland (P). The appearance of the parotid gland on T1- and T2-weighted (not shown) is normal (see Fig 1A). Arrow, spinal cord.

B, Diffusion-weighted MR image through the same level demonstrating manually defined regions of interest over the parotid gland (P) and spinal cord (arrow).

C, ADC map with manually defined regions of interest over the parotid gland (P) and spinal cord (arrow).

Data Analysis

We compared the right and left parotid gland ADC data by using the Wilcoxon sign rank test. We segregated the patients into two groups on the basis of the history of underlying CTD. To determine a statistically significant difference between the two groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed. We further compared spinal cord ADC values from our population with those of previously reported values (30) also by using two-sample Mann-Whitney U test. All statistical analyses were performed by using Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) and Intercooled Stata 6.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Non-CTD Patients

A total of 90 patients with no known history of CTD (36 men and 75 women; mean age, 41 years) were included. The right and left parotid glands were initially analyzed separately. The mean ADC value of the left parotid gland was 0.47 ± 0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.42 × 10−3, 0.52 × 10−3); the mean ADC value of the right parotid gland was 0.53 ± 0.29 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.47 × 10−3, 0.59 × 10−3) (Table 1). The difference between the left and right ADC values was not significant (P = .60). When the data for the left and right parotid glands were combined, the average ADC value of the parotid gland was 0.50 ± 0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.44 × 10−3, 0.56 × 10−3). We further segregated patients by sex after combining parotid glands. There was a statistically significant difference (P = .01) in ADC values accounting for sex, where mean ADC in men was 0.44 ± 0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s; in women, 0.54 ± 0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s.

Table I:

Comparison of apparent diffusion coefficients (ADCs) between patients with and without a history of systemic connective tissue disorders (CTD)

| Non-CTD Meana (95% CIb) | CTD Mean (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Parotid: | ||

| Leftc | 0.47 (0.42, 0.53) | 0.98 (0.75, 1.20) |

| Rightc | 0.53 (0.47, 0.59) | 0.95 (0.73, 1.17) |

| Combinedc | 0.50 (0.44, 0.56) | 0.96 (0.79, 1.25) |

| Spinal cord | 0.98 (0.93, 1.04) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.25) |

ADC values expressed in units of (× 10−3 mm2/sec).

95% confidence intervals.

ADCs of the parotid glands are statistically significantly different (P <.05) between patients with and without a history of CTD; however, there is no difference in ADCs of the spinal cord.

As an internal control, the mean ADC value of the spinal cord in a representative sample of these patients (n = 54) was 0.98 ± 0.18 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.93 × 10−3, 1.03 × 10−3). We validated our internal control with the previously published value (30) of 1.11 ± 0.14 × 10−3 mm2/s (mean ± SD) and found no statistically significant difference (P = .75).

CTD Patients

A total of seven patients with a known history of CTD (seven women; average age, 48 years) were included. Initially, the right and left glands were analyzed separately (Table 2). There was no qualitative difference in the MR appearance on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images between the parotid glands of patients with CTD compared with our normal cohort. There was no radiographic evidence of sialadenitis or sialosis in the parotid glands of patients with CTD. The mean ADC value of the left parotid gland was 0.98 ± 0.31 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.75 × 10−3, 1.20 × 10−3); the mean ADC value of the right parotid gland was 0.95 ± 0.29 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.73 × 10−3, 1.17 × 10−3). The difference between the left and right ADC values was not significant (P = .22). When the data for the left and right parotid glands were combined, the mean ADC value was 0.96 ± 0.24 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.79 × 10−3, 1.14 × 10−3) (Table 2).

Table II:

Comparison of parotid apparent diffusion coefficients (ADCs) in connective tissue disorder (CTD) patients

| Patient No. | Diagnosis | Parotid ADCa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leftb | Rightb | Combined | ||

| 1 | SLE | 1.43 | 1.17 | 1.30 |

| 2 | SLE | 0.45 | 1.12 | 0.79 |

| 3 | SLE | 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| 4 | SLE | 0.80 | 0.45 | 0.63 |

| 5 | SLE | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.80 |

| 6 | DLE | 1.16 | 1.05 | 1.11 |

| 7 | Sjogren’s | 1.06 | 1.26 | 1.16 |

| Average | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.96 | |

Note.—SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus

ADC values expressed in units of (× 10−3 mm2/sec).

Average ADCs of the left and right parotid glands are not statistically significantly different (P < .05).

As an internal control, the mean ADC value of the spinal cord in these patients was 1.04 ± 0.29 × 10−3 mm2/s (95% CI, 0.83 × 10−3, 1.25 × 10−3), which was not significantly different from the non-CTD group (P = .87). Also, the mean ADC value of the spinal cord in these patients was not significantly different from previously published studies (P = .54) (30).

The ADC values for the left, right, and combined parotid glands for the CTD patients, however, were significantly higher than those of non-CTD parotid glands (P < .005; Table 1). Because all patients with CTD were women and we noted differences in ADC values on the basis of sex, we further compared CTD patients with female non-CTD patients. The difference remained statistically significant (P < .0002).

Discussion

We have characterized the distribution of the ADC values in the normal, non-CTD parotid gland for our study population. The lack of statistical difference between the ADC value of the left and right parotid glands in both groups shows consistency in our data collection. Also, our ADC results may be translatable to other ADC studies that have been previously published, in light of the consistency of our spinal cord data as compared with data of previous investigations (30).

In a recently published study by Sumi et al (32), the ADC value in the normal parotid gland in their population was 0.28 ± 0.01 × 10−3 mm2/s. These results are not significantly different from our data by using the Mann-Whitney test (P = .49) and validate the results of our non-CTD parotid gland ADC values that we used to compare with our CTD parotid gland results.

Our results suggest there is less restricted diffusion (increase in ADC) in the parotid gland of CTD patients than that found in normal patients, even accounting for sex. The increase in ADC seen in early parotid involvement in CTD patients may be due to various causes. Sumi et al (32) suggested that elevated ADC values in the CTD population could be due to intraparotid edema in patients with early sialadenitis (32). By contrast, Sumi et al reported a decrease in ADC in patients with late stage clinically evident disease. The fact that our patients had no radiographic abnormalities on standard T1- and T2-weighted images and had no salivary dysfunction indicates that the parotid changes in our population are mild and are in the early stages of disease. It is possible that the elevated ADC values in patients with CTD may be due to early cellular infiltration. Studies of CTD patients and CTD mouse models have shown that early sialadenitis results in focal periductal lymphocytic infiltration and dilated intraglandular ducts with a slight increase in the interlobular fibrous tissue (33, 34). It is possible that the increase in unrestricted diffusion identified in our affected population could be caused by early lymphocellular infiltrate in the parotid glands (35, 36).

We feel that ADCs may be used to evaluate the parotid gland and to detect parotid abnormalities in patients with systemic connective tissue disorders that are not identified by standard imaging. It is also possible that ADC mapping will be able to diagnose parotid disease before the onset of clinical signs. This may affect prognosis by allowing early intervention of certain disorders. The treatment of salivary dysfunction in patients with Sjögren syndrome and other connective tissue disorders is largely empirical and symptomatic (36). Analgesics and antiinflammatory drugs are used for symptomatic relief and to reduce further damage to tissues (36). In addition to providing symptomatic relief, treatment is aimed at reducing the damaging effects of chronic xerostomia by substituting the missing secretions (36). Also, preventive dental care and personal hygiene are important in reducing the long-term complications of these disorders (36). It is possible that earlier diagnosis and treatment of parotid involvement in these patients may lead to a reduction in symptoms and long-term complications; however, future studies will be necessary to confirm this.

This study is a preliminary evaluation of the feasibility of applying ADCs in the evaluation of nonbrain structures, in particular the parotid gland. Although the results are encouraging, in view of the apparent detectable differences in ADC values based on presence or absence of CTD, further studies replicating and validating our findings need to be performed. This may include a prospective trial enrolling patients with and those without CTD or an assessment of the response to therapy by using ADC values as an indicator of parotid parenchymal status.

There are certain limitations associated with our study. We present the ADC means and confidence intervals for our population as standard descriptive statistics, the calculations of which are based on a normal distribution. The 95% CI of our non-CTD population compared with Sumi et al do not overlap, which suggests a statistically significant difference between two populations assumed to have a normal distribution. In comparing our values with Sumi et al, we did not make such an assumption and used a nonparametric test. Consequently, we believe that the results of nonparametric testing (Mann Whitney) more accurately compare the two means, rather than comparing them by using the 95% CI. Further, heterogeneity in our patient population may have contributed to the relatively wide distribution of ADC values in our study. It is interesting that there appears to be a sex-based difference in ADC values in our population. This is of uncertain significance and may be related to differences in fat content of the parotids.

Diffusion-weighted imaging is based on echo-planar imaging that permits rapid imaging with reduced motion artifacts. The disadvantages are relatively low signal-to-noise ratios and image degradation due to susceptibility artifacts. Our standard echo planar imaging technique attempts to minimize susceptibility artifacts due to air-bone-tissue interfaces by using a high-bandwidth echo planar sequence with thin sections, although we do not use an antisusceptibility device. Further, heterogeneity in fat content of the parotid glands across the patient population may have manifested different levels of chemical shift artifacts, contributing to some of the variability in parotid ADC values. All patients were imaged in a standard head coil. As a result, the complete extent of the parotid gland was not included in the study. The parotid regions of interest were obtained from an area that was felt to be most representative of the parotid gland. Also, the sample size for our CTD population was relatively small.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that the parotid glands in patients with CTD and no parotid-referable complaints have higher ADC values than the parotid glands in patients without CTD. When compared with our normal values, ADC mapping of the parotid gland may be a useful adjunct in the detection of parotid involvement in patients with CTD. This information may be used to identify patients with parotid abnormalities before development of clinical symptoms or imaging abnormalities detectable current standard techniques.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill Philp and Claudia Koitch for their assistance in the collection of patient information and their software technical support. Also, we thank Nita Patel for assisting in the retrieval of the hardware information and image acquisition parameters. Finally, we thank Matthew Thompson for his assistance in converting images for submission.

Footnotes

R.C.C. supported in part by the GE-AUR Radiology Research Academic Fellowship.

Presented at the 40th annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology, Vancouver, B.C., May 11–17, 2002.

References

- 1.Beitler JJ, Smith RV, Brook A, et al. Benign parotid hypertrophy on +HIV patients: limited late failures after external radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;5:451–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Molen AJ, Wilmink JT. Cystadenolymphoma of the parotid gland. JBR-BTR 2000;83:30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Stefani A, Lerda W, Bussi M, Valente G, Cortesina G. [Tumors of the parapharyngeal space: case report of clear cell myoepithelioma of the parotid gland and review of literature]. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 1999;19:276–282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsuno S, Ishii K, Otsuka A, Ezawa S, Usami S. Bilateral basal-cell adenomas in the parotid glands. J Laryngol Otol 2000;114:83–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MA, Docktor JW. Acute suppurative parotitis with spread to the deep neck spaces. Am J Emerg Med 1999;17:46–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robson CD, Hazra R, Barnes PD, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection of the head and neck in immunocompetent children: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:1829–1835 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menauer F, Jager L, Leunig A, Grevers G. Role of diagnostic imaging in chronic recurrent parotitis in childhood [in German]. Laryngorhinootologie 1999;78:497–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Califano J, Eisele DW. Benign salivary gland neoplasms. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1999;32:861–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn MS, Hayashi GM, Hilsinger RL Jr, Lalwani AK. Familial mixed tumors of the parotid gland. Head Neck 1999;21:772–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumi M, Izumi M, Yonetsu K, Nakamura T. Sublingual gland: MR features of normal and diseased states. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;172:717–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branstetter BF 4th, Weissman JL. Normal anatomy of the neck with CT and MR imaging correlation. Radiol Clin North Am 2000;38:925–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iqbal S, Sher MR, Good RA, Cawkwell GD. Diversity in presenting manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus in children. J Pediatr 1999;135:500–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mafee MF, Edward DP, Koeller KK, Dorodi S. Lacrimal gland tumors and simulating lesions: clinicopathologic and MR imaging features. Radiol Clin North Am 1999;37:219–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haller JR. Trauma to the salivary glands. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1999;32:907–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander EL, Beall SS, Gordon B, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebral lesions in patients with the Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1988;108:815–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith FW, Deans HE, McLay KA, Rayner CW. Magnetic resonance imaging of the parotid glands using inversion-recovery sequences at 0.08 T. Br J Radiol 1988;61:480–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber AL, Siciliano A. CT and MR imaging evaluation of neck infections with clinical correlations. Radiol Clin North Am 2000;38:941–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohbayashi N, Yamada I, Yoshino N, Sasaki T. Sjögren’s syndrome: comparison of assessments with MR sialography and conventional sialography. Radiology 1998;209:683–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heverhagen JT, Kalinowski M, Rehberg E, et al. Prospective comparison of magnetic resonance sialography and digital subtraction sialography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2000;11:518–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goto TK, Yoshiura K, Nakayama E, et al. The combined use of US and MR imaging for the diagnosis of masses in the parotid region. Acta Radiol 2001;42:88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makula E, Pokorny G, Kiss M, et al. The place of magnetic resonance and ultrasonographic examinations of the parotid gland in the diagnosis and follow-up of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2000;39:97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharafuddin MJ, Diemer DP, Levine RS, et al. A comparison of MR sequences for lesions of the parotid gland. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16:1895–1902 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogl TJ, Dresel SH, Spath M, et al. Parotid gland: plain and gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 1990;177:667–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Correa AJ, Burkey BB. Current options in management of head and neck cancer patients. Med Clin North Am 1999;83:235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabinov, JD. Imaging of salivary gland pathology. Radiol Clin North Am 1999;381047–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tambouret R, Geisinger KR, Powers CN, et al. The clinical application and cost analysis of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of mass lesions in sarcoidosis. Chest 2000;117:1004–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Späth M, Krüger K, Dresel S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the parotid gland in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol 1991;18:1372–1378 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baird AE, Warach S. Magnetic resonance imaging of acute stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998;18:583–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherji SK, Chenevert TL, Castillo M. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. J Neuroophthalmol 2002;22:118–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Takashima S, Takayama F, et al. Head and neck lesions: characterization with diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology 2001;220:621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holder CA, Muthupillai R, Mukundan S, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the normal human spinal cord in vivo. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:1799–1806 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sumi M, Takagi Y, Uetani M, et al. Diffusion-weighted echoplanar MR imaging of the salivary glands. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;178:959–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takashima S, Morimoto S, Tomiyama N, et al. Sjögren’s syndrome: comparison of sialography and ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound 199220:99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayashi T, Shirachi T, Hasegawa K. Relationship between sialoadenitis and periductal laminin expression in the submandibular salivary gland of NZBxNZWF(1) mice. J Comp Pathol 2001;125:110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takashima S, Takeuchi N, Morimoto S, et al. MR imaging of Sjögren’s syndrome: correlation with sialography and pathology. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1991;15:393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manoussakis MN, Montsopoulos HM. Sjögren’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1999;32:843–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]