Abstract

Summary: We report a case of spinal intradural schwannoma presenting with intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral angiography studies were negative, but MR imaging of the spine revealed a large hemorrhagic tumor in the thoraco-lumbar junction. The tumor was misdiagnosed as ependymoma of the conus medullaris. This case illustrates the importance of a high index of suspicion for spinal disease in angiographically-negative subarachnoid hemorrhage and pitfalls in MR diagnosis of thoraco-lumbar tumors.

Patients with spinal abnormalities infrequently present with intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), accounting for less than 1% of all patients with SAH. The more common causes include spinal trauma, arteriovenous malformations, and saccular aneurysms of spinal arteries (1, 2). On occasion, spinal cord tumors, either primary or metastatic, may cause cranial SAH, with ependymoma of the conus medullaris accounting for most of these cases (1, 3). Spinal nerve sheath tumors such as schwannomas only rarely cause SAH, especially in the absence of spinal cord or nerve root symptoms. We report a case of thoraco-lumbar schwannoma presenting clinically with intracranial SAH and illustrate the diagnostic difficulties for the neuroradiologist and neurosurgeon.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man presented with fever, neck pain, and altered mental status. Except for nuchal rigidity, physical examination was normal. CT of the head revealed hyperattenuation in the cortical sulci bilaterally consistent with acute SAH (Fig 1). There was no other intracranial abnormality. A lumbar puncture yielded bloody and xanthochromic CSF. Cerebral angiography was performed on two occasions, 1 and 12 days after admission, but was negative for aneurysm, vascular malformations, or tumor on both occasions. No vasospasm was detected. On direct systemic review of spinal symptoms, the patient gave a history of vague generalized backache for many years, without precipitating or aggravating events. He also had mild symptoms of hesitancy and poor stream of urine. Spinal neurologic examination, however, was again normal, and digital rectal examination revealed a moderately enlarged prostate gland. An MR examination of the whole spine was performed. A 5 × 2 × 2-cm mass at the conus medullaris was found extending from T11 to L1 vertebral levels (Fig 2). It was centrally located and was indistinguishable from the conus medullaris (Fig 2D). The lesion showed heterogeneous signal intensity and susceptibility effect on gradient-recalled echo images, consistent with blood degradation products. There was thick, irregular rim enhancement after intravenous contrast, medium administration (Fig 2C). Immediately caudal to the mass, there were two separate abnormal focal collections of increased signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images compared with the spinal cord and nerve roots. These were located intradurally, both anterior and posterior to the cauda equina, and clearly separated form the hyperintense CSF and the epidural fat (Fig 3), consistent with subdural hematoma (SDH) (4). A diagnosis of conus ependymoma causing SAH and SDH was made and the patient proceeded to surgery.

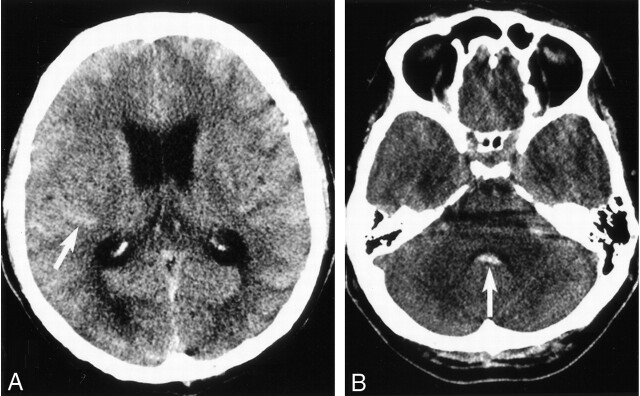

Fig 1.

SAH. Unenhanced axial CT section of the brain (A) showing hyperattenuated cortical sulci (arrow) and (B) fourth ventricle (arrow) consistent with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage.

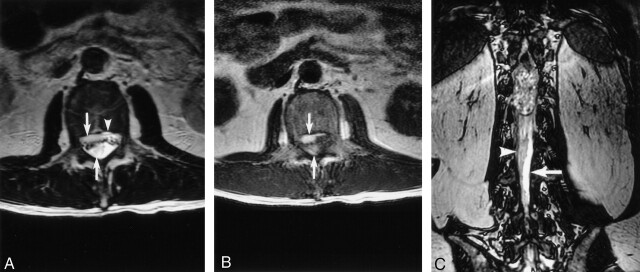

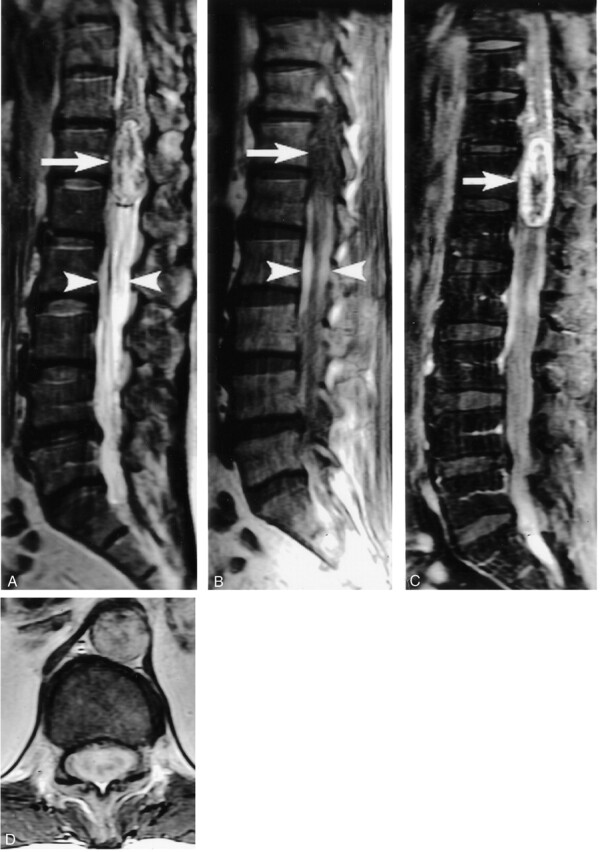

Fig 2.

Thoraco-lumbar spinal tumor. Sagittal T2- (A) and T1-weighted images (B) show a large mass at the conus medullaris with heterogeneous signal intensity (arrows). The two hyperintense SHDs may be seen located caudal to the mass (arrowheads).

After intravenous contrast material injection (C and D), there is heterogeneous enhancement of the mass.

Fig 3.

Spinal SDH. Axial T2- (A) and T1-weighted (B) images show hyperintense subdural blood collections located both anterior and posterior (arrows) to the cauda equina. Anteriorly, the subdural blood is separate from the epidural fat signal intensity (A, arrowhead). Coronal fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition (C) shows the posterior blood collection (arrowhead) is clearly separate from the hyperintense CSF (arrow).

A grayish white, intradural-extramedullary tumor was found at surgery, with intrathecal blood clot surrounding its lower end. Gross pathology showed a poorly circumscribed mass with whitish capsular tissue. Cut section showed tanned tissue with focal firm whitish areas. On histopathology, the tumor was found to be composed of spindle cells arranged in vaguely alternating cellular and loosely textured areas (Antoni A and B, respectively) with the former predominating. The cellular areas revealed fascicles and whorls of spindle cells with nuclear palisades and tight aggregates of Verocay bodies. Hyalinized vessels, perivascular siderophage deposition, and ectatic blood vessels were also seen. There was mild to moderate cellular pleomorphism, but no features of malignant transformation. The final diagnosis was schwannoma with degenerative changes.

Discussion

Spinal causes of SAH are rare, representing 1.5% of all cases of SAH (5). Halpern et al (6) reported 0.6% of their cases of SAH to have spinal origin, whereas Sahs et al (7) reported an even lower incidence, 0.05%. SAH from spinal tumors tends to occur in younger patients between the 2nd and 4th decades of life (8, 9, 10). The clinical presentation depends on the amount of bleeding, with massive hemorrhage resulting in sudden, rapidly evolving classic symptoms of back pain with or without neurologic deficit (3). Michon (11) in 1928 gave the first description of spinal SAH, which he likened to being stabbed in the spine (le coup de poignard rachidien). In the absence of pain, predominant motor and spinchteric deficits have been reported (12).

The more common causes of spinal SAH include trauma and vascular malformations (1, 2, 9, 13). Among the spinal tumors, conus ependymoma accounts for most of the cases of SAH (1, 3). Nerve sheath tumors may also cause SAH, but it is exceedingly rare for these intradural lesions to come to clinical attention with only intracranial SAH without spinal symptoms. In our literature review, we identified 20 reports of spinal nerve sheath tumors that caused SAH, of which only seven cases (28%) presented exclusively with intracranial symptoms like our patient (6, 8–10, 13, 14–27) (Table).

Spinal nerve sheath tumors presenting with intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage

| Case No | Series (Reference) | Tumor Histology | Site | Clinical Presentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andre-Thomas et al 1930 (15) | Schwannoma | L2–L3 | Spinal |

| 2 | Krayenbuhl 1947 (16) | Schwannoma | Cauda equina | Spinal |

| 3 | Krayenbuhl 1947 (16) | Schwannoma | T12 | Spinal |

| 4 | Fincher 1951 (17) | Schwannoma | T12–L1 | Spinal |

| 5 | Halpren et al 1958 (6) | Neurofibroma | L2 | Spinal |

| 6 | Prieto and Cantu 1967 (18) | Neurofibroma | Cauda equina | Spinal |

| 7 | Fortuna and La Torre 1968 (19) | Schwannoma | Cauda equina | Spinal |

| 8 | Bernell et al 1973 (20) | Malignant neurofibroma | Cauda equina | Intracranial |

| 9 | Grollmuss 1976 (21) | Schwannoma | T8–T11 | Spinal |

| 10 | Djindjian et al 1978 (10) | Schwannoma | L1 | Spinal |

| 11 | Luxon and Harrison 1978 (22) | Schwannoma | Cervical | Intracranial |

| 12 | Muhtaroglu and Strenge 1981 (23) | Schwannoma L1–L2 | Intracranial | |

| 13 | Motomochi et al 1981 (24) | Schwannoma | Thoracic | Spinal |

| 14 | De Divitiis et al 1985 (8) | Schwannoma | Cervical | Intracranial |

| 15 | Chalif et al 1990 (14) | Schwannoma | C1–2 | Intracranial |

| 16 | Bruni et al 1991 (9) | Neurofibroma | L1–L2, L2–L3, L3–L4 | Spinal |

| 17 | Mills et al 1993 (25) | Schwannoma | C7–T1 | Spinal |

| 18 | Bonicki et al 1993 (26) | Schwannoma | Cauda equina | Intracranial |

| 19 | Correiro et al 1996 (27) | Schwannoma | C6–T1 | Intracranial |

| 20 | Cordon et al 1999 (13) | Schwannoma | L1–L2 | Spinal |

Schwannomas are well-circumscribed intradural or extradural or combined intraextradural tumors located on peripheral nerves or spinal nerve roots (28). Hemorrhage is unusual in this tumor, and various theories, including tumor location and histologic features, have been proposed to explain this phenomenon (8, 22, 25, 29). According to the vascular theory, ectatic and hyalinized vessels of the tumor may undergo spontaneous thrombosis, followed by distal tumor necrosis and hemorrhage (25). The mechanical theory (8, 13, 22, 25), on the other hand, suggests that hemorrhage into subarachnoid space occurs when there is trauma at the interface between the tumor and the normal neural tissue, particularly at the conus medullaris and the cauda equina (13, 25). This may be due to the differences in inertia between the tumor of the spinal cord and the cauda equina, resulting in abnormal movement at their interface. Traction on vascular attachments to nerve roots may also occur, leading to disruption of the blood vessels on the surface of the tumor (30). Such tractional forces occur most commonly in areas of high mobility, and this probably explains why the onset of symptoms in 50% of cases is related to exertion (25, 27). Other causes of hemorrhage due to central ischemic necrosis associated with tumor growth (28, 29) or malignant transformation and neovascularization can further increase the susceptibility of such tumors to hemorrhage by accelerating the process mentioned above, especially within large schwannomas (20).

In our case, there was no clear history of exertion or pathologic evidence of malignant transformation. We believe that the degenerative changes, along with the mechanical stress at the conus, caused rupture of the fragile, ectatic tumor vessels and subsequent dissection of the blood into the subarachnoid space. This probably led to the loss of the typical plane of demarcation that separates the tumor from the normal conus medullaris at MR imaging, giving rise to misdiagnosis of a conus ependymoma. Even without tumor hemorrhage, ependymomas of the conus medullaris and cauda equina and schwannomas may be indistinguishable by imaging features alone (31). Although ependymomas tend to have more cystic and hemorrhagic changes and are more commonly associated with SAH (30, 31), these findings were not helpful in our case. In retrospect, the presence of spinal SDH immediately caudal to the tumor is interesting and may have been helpful in differential diagnosis (4). Nontraumatic spinal SDH is rare and may rarely be related to spinal tumors. In our literature review, schwannomas (32, 33, 34), as well as an ependymoma (35), have been described. In hindsight, it should have been possible to suggest nerve sheath tumor as a strong differential diagnosis.

Our patient presented a diagnostic challenge in clinical presentation of SAH without spinal symptoms. Conventional cerebral angiography is the method of choice to diagnose arterial aneurysm, the most common cause of SAH. Intracranial and systemic causes of SAH with negative cerebral angiographic findings include microaneurysms of perforating vessels, thrombosed or obliterated aneurysms, cryptic arteriovenous malformations, cranial tumors, trauma, blood dyscrasias, and infection (14, 31, 36). Although the number of aneurysms detected at repeat angiography is low (37, 38), at our institution all patients with an initial negative angiogram undergo a second study 1–2 weeks later. If the second angiographic study is also negative, and other abnormalities are excluded, the patient is followed up clinically without further investigation because patients with negative angiograms are known to have a better prognosis compared with those with ruptured aneurysms (39). Although a few authors have recommended MR imaging of the spine in patients with negative angiograms (8, 14), this is not the routine practice at our institution in patients without spinal signs or symptoms. In our patient, the vague symptom of backache without localizing neurologic deficits was only forthcoming on direct questioning and was not deemed significant by the patient himself. We believe this case demonstrates the importance of a thorough systemic review and a high index of clinical suspicion for spinal disease.

References

- 1.Cummings TM, Johnson MH. Neurofibroma manifested by spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;162:959–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders FW, Birchard D, Willimer J. Spinal artery aneurysm. Surg Neurol 1987;27:269–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scotti G, Filizzolo F, Scialfa G, Tampieri D. Repeated subarachnoid hemorrhages from a cervical meningiomas. J Neurosurg 1987;66:779–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Post MJ, Becerra JL, Parley WM, et al. Acute spinal subdural hematoma: MR and CT findings with pathologic correlates. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:1895–1905 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walton JN. Subarachnoid hemorrhage of unusual aetiology. Neurology 1953;3:517–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halpren J, Feldman S, Peyser E. Subarachnoid hemorrhage with papilledema due to spinal neurofibroma. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1958;79:138–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahs AL, Perret GE, Locksley HB, Nishioka H, eds. Intracranial aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott;1969

- 8.De Divitiis E, Maiuri F, Corriero G, Donzelli R. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to spinal neurinoma. Surg Neurol 1985;24:187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruni P, Esposito S, Oddi G, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage from multiple neurofibromas of the cauda equina: case report. Neurosurgery 1991;28:910–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Djindjian M, Djindjian R, Huth M, et al. Les hemorrhagies meningees spinales tumorales: a propos de 5 cas arterographies. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1978;134:685–692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michon P. Le coup de poignard rachidien: symptome initial de certaines hemorragies sousarachnoidiennes. Essai sur les hemorragies meningees spinales Presse Med 1928;36:964–966 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell FG. Painless tumors of the region of the cauda equina: a case report. Neurology 1963;13:341–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordon T, Bekar A, Yaman O. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage attributable to schwannoma of the cauda equina. Surg Neurol 1999;51:373–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalif DJ, Black K, Rosenstein D. Intradural spinal cord tumour presenting as a subarachnoid hemorrhage: magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis. Neurosurgery 1990;27:631–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andre-Thomas F, Schaeffer H, De Martel T. Syndrome d’hemorrhagie meningee realise par une tumeur de la queue de cheval. Paris Med 1930;77:292–296 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krayenbuhl H. Spontane spinale Subarachnoidalblutung und akute Ruckenmarkskompression bei intraduralem spinalem Neurinom. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1947;77:692–694 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fincher EF. Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage in intradural tumours of the lumber sac. J Neurosurg 1951;8:576–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prieto A, Cantu RC. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with neurofibroma of cauda equina. J Neurosurg 1967;27:63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortuna A, La Torre E. Neurinoma della cauda con emorragia subarcnoidea circoscritta. Il Lavaro Neuropsichiatrico 1968;43:1157–64 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernell WR, Kepes JJ, Clough CA. Subarachnoid hemorrhage from malignant schwannoma of the cauda equina. Tex Med 1973;69:101–104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grollmuss J. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage with schwannoma. Acta Neurochir (Wein) 1975;31:253–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luxon LM, Harrison MJ. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and papilledema due to a cervical neurilemmoma: case report. J Neurosurg 1978;48:1015–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhtaroglu U, Strenge H. Recurrent subarachnoid haemorrhage with spinal neurinoma [author’s translation]. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1980;23:151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motomochi M, Makita Y, Nabeshima S, et al. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage due to a thoracic neurinoma during anticoagulation therapy: a case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1981;21:781–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills B, Marks PV, Nixon JM. Spinal subarachnoid haemorrhage from an “ancient” schwannoma of the cervical spine. Br J Neurosurg 1993;7:557–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonicki W, Koszewski W, Marchel A, Sherif A. Caudal tumors as a rare cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Neurochir Pol 1993;27:599–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correiro G, Iacopino DG, Valentini S, Lanza PL. Cervical neuroma presenting as a subarachnoid hemorrhage: case report. Neurosurgery 1996;39:1046–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parmar H, Patkar D, Gadani S, Shah J. Cystic lumbar nerve sheath tumours: MRI features. Australas Radiol 2001;45:123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakamato M, Harayama K, Furufu T. A case of cystic spinal schwannoma presented unusual clinical findings. Orthopedics 1985;3:1185–1189 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Argyropoulou PI, Argyropoulou MI, Tsampoulas C, et al. Myxopapillary ependymoma of the conus medullaris with subarachnoid haemorrhage: MRI in two cases. Neuroradiology 2001;43:489–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexander MS, Dias PS, Uttley D. Spontaneous sunarachnoid hemorrhage and negative cerebral panangiography. J Neurosurg 1986;64:537–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng PY. Schwannoma of the cervical spine presenting with acute haemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci 2001;8:277–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vazquez-Barquero A, Pascual J, Quintana F, et al. Cervical schwannoma presenting as a spinal subdural haematoma. Br J Neurosurg 1994;8:739–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roscoe MW, Barrington TW. Acute spinal subdural hematoma: a case report and review of literature. Spine 1984;9:672–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith RA. Spinal subdural hematoma, neurilemmoma and acute transverse myelopathy. Surg Neurol 1985;23:367–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayward RD. Subarachnoid hemorrhage of unknown etiology: a clinical and radiological study of 51 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1977;40:926–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forster DM, Steiner L, Hakason S, Bergvall U. The value of repeat panangiography in cases of unexplained subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1978;48:712–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juul R, Fredriksen TA, Ringkjob R. Prognosis in subarachnoid hemorrhage of unknown etiology. J Neurosurg 1986;64:359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eskesen V, Sorensen EB, Rosenorn J, Schmidt K. The prognosis in subarachnoid hemorrhage of unknown etiology. J Neurosurg 1984;61:1029–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]