Key Points

Question

What neuroanatomical changes are associated with symptoms after mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), and when is the optimal time for acute imaging?

Findings

In this multicenter cohort study, 81 patients with mTBI underwent advanced magnetic resonance imaging within 72 hours and 2 to 3 weeks after injury. White matter volume and integrity evolved during that window in tandem with symptoms and were most closely associated with clinical recovery if imaging was performed within 72 hours.

Meaning

These findings suggest that white matter injury is associated with symptoms after mTBI and could, if detected early, help select patients at risk of poor outcome for clinical follow-up or interventional trials.

This multicenter cohort study assesses neuroanatomical substrates in patients with mild traumatic brain injury and the optimal timing for magnetic resonance imaging.

Abstract

Importance

Persistent symptoms after mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) represent a major public health problem.

Objective

To identify neuroanatomical substrates of mTBI and the optimal timing for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective multicenter cohort study encompassed all eligible patients from the Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) study (December 19, 2014, to December 17, 2017) and a local cohort (November 20, 2012, to December 19, 2013). Patients presented to the hospital within 24 hours of an mTBI (Glasgow Coma Score, 13-15), satisfied local criteria for computed tomographic scanning, and underwent MRI scanning less than 72 hours (MR1) and 2 to 3 weeks (MR2) after injury. In addition, 104 control participants were enrolled across all sites. Data were analyzed from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2020.

Exposure

Mild TBI.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Volumes and diffusion parameters were extracted via automated bespoke pipelines. Symptoms were measured using the Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire in the short term and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale at 3 months.

Results

Among the 81 patients included in the analysis (73 CENTER-TBI and 8 local), the median age was 45 (interquartile range [IQR], 24-59; range, 14-85) years, and 57 (70.4%) were male. Structural sequences were available for all scans; diffusion data, for 73 MR1 and 79 MR2 scans. After adjustment for multiple comparisons between scans, visible lesions did not differ significantly, but cerebral white matter volume decreased (MR2:MR1 ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-0.99) and ventricular volume increased (MR2:MR1 ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02-1.10). White matter volume was within reference limits on MR1 scans (patient to control ratio, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97-1.01) and reduced on MR2 scans (patient to control ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-0.99). Diffusion parameters changed significantly between scans in 13 tracts, following 1 of 3 trajectories. Symptoms measured by Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire scores worsened in the progressive injury phenotype (median, +5.00; IQR, +2.00 to +5.00]), improved in the minimal change phenotype (median, −4.50; IQR, −9.25 to +1.75), and were variable in the pseudonormalization phenotype (median, 0.00; IQR, −6.25 to +9.00) (P = .02). Recovery was favorable for 33 of 65 patients (51%) and was more closely associated with MR1 than MR2 (area under the curve, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.78-0.96] vs 0.75 [95% CI, 0.62-0.87]; P = .009).

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that advanced MRI reveals potential neuroanatomical substrates of mTBI in white matter and is most strongly associated with odds of recovery if performed within 72 hours, although future validation is required.

Introduction

Estimated to affect half the world’s population during their lives, traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major public health problem and a leading cause of disability.1 Based on the level of consciousness on presentation, 70% to 90% of TBI is classified as mild.1 This term, however, is clearly a misnomer, because 30% to 50%2,3,4,5 of those patients experience symptoms that persist beyond 6 months and disrupt relationships and employment.6 Although symptoms may be reduced by early intervention,4,7 the large numbers of patients with mild TBI (mTBI) prohibit unselected follow-up without overburdening the system. Similarly, because many patients recover fully, trials of early interventions using unselected populations with mTBI are underpowered. We therefore need ways to enrich populations for clinical follow-up and interventional trials. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers the potential to improve our understanding of the pathophysiology underpinning patient outcomes and to identify patients at risk of unfavorable recovery.

Results of conventional imaging, including radiographic computed tomography (CT) and structural MRI, are often normal in patients with persisting symptoms and do not explain all of the variance in outcome.8,9,10 More advanced MRI, including volumetric analysis and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), have shown promise in detecting anatomical changes associated with outcome after mTBI, such as traumatic axonal injury.11,12 Diffusion tensor imaging characterizes the diffusion of water molecules, which is influenced by the microstructural organization of tissues, offering unique pathophysiological insights.13 Studies of mTBI tended to perform imaging at a single point more than 1 week after injury.8,11 Changes, however, are likely dynamic in the early phase, and hence the timing of imaging sessions may prove important. This supposition is supported by a systematic review of DTI in the acute to subacute phase,14 which found conflicting results, with equal numbers of studies reporting increases and decreases in fractional anisotropy, a marker of white matter integrity. The optimal timing of imaging therefore remains uncertain.

There are no validated outcome prediction models for use in the emergency department. Emergency physician clinical judgment for the estimation of long-term outcomes is overly optimistic, expecting complete recovery in more than 90% of patients, when only approximately 50% achieve it.15 Although there are several outcome prediction models for TBI, the well-established ones (CRASH [Corticosteroid Randomization After Significant Head Injury Trial]16 and IMPACT [International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials]17) are primarily aimed at moderate to severe TBI. Two reviews18,19 concluded that no available models adequately predict recovery after mTBI. These reviews did not include the prediction model of the UPFRONT study,3 which still depends on a psychological assessment at 2 weeks. Thus, an urgent need remains for a tool that risk-stratifies patients early after presentation.

This study investigated 3 questions regarding MRI in mTBI. First, what are the neuroanatomical substrates of mTBI? Second, how do these substrates change with evolving or resolving symptoms? Third, what is the optimal timing for estimating outcomes?

Methods

Participants

All eligible patients were included in this cohort study from 2 prospective observational cohorts: the Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) study (December 19, 2014, to December 17, 2017)20,21 and a Cambridge study (November 20, 2012, to December 19, 2013) with a similar protocol.22,23 CENTER-TBI was accessed using the Neurobot platform (RRID/SCR_017004, core data, version 2.0; International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility; released May 15, 2019). Ethical approval for CENTER-TBI was obtained in accordance with all relevant laws and regulations for each recruiting site. For the Cambridge cohort, ethical approval was obtained from the local research committee. Informed consent from the patient or legal representative/next of kin was obtained for all participants. Reporting of this study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline.

Patients sustained an mTBI (Glasgow Coma Score on presentation, 13-15), satisfied local criteria for CT head imaging, and underwent an initial MRI within 72 hours (MR1) and a second MRI within 31 days (2-3 weeks) of injury (MR2). Thirty-nine patients underwent a third MRI (MR3) at 3 months. Across 9 sites, 12 MRI scanners each contributed 6 to 25 healthy volunteers of comparable age and sex who underwent imaging with the same protocol (n = 104).

Demographic and clinical data were collected in the emergency department. Follow-up included the Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ)24 at the time of imaging (<72 hours and 2-3 weeks) and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale25 at 3 months.

Image Acquisition and Analysis

Computed tomographic data were obtained using local site protocols, with no attempt at standardization. Magnetic resonance imaging sequences were acquired at 3 T and included volumetric T1-weighted, volumetric fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, T2-weighted, and susceptibility-weighted imaging and DTI. Base values of DTI were 2-mm isotropic voxels, 32 noncollinear directions, and a b value of 1000 seconds/mm2 or 2-mm isotropic voxels, 63 noncollinear directions, and a b value of 1000 seconds/mm2 (Cambridge).23,26 Computed tomographic and MRI scans were reported centrally by Cambridge or icometrix investigators blinded to patient outcome based on Common Data Elements and using all available sequences.27

Sequences were processed on a TBI-specific pipeline. After neck cropping and correcting for scanner field inhomogeneities, brain parcellation was performed using multi-atlas label propagation with expectation-maximization–based refinement, which provides robust segmentation even when anatomy is distorted owing to trauma.28 The 138 anatomical regions were collapsed into 15 regions of interest (ROIs).

All DTI data were corrected for noise,29,30 Gibbs ringing artifacts,31 head motion and eddy current artifacts,32 and inhomogeneities in the magnetic field.33 Diffusion tensors were fitted via weighted least squares to derive mean diffusivity and fractional anisotropy maps using the FMBIR Software Library. White matter parcellation into 72 tracts was performed using TractSeg.34

Raw data and pipeline outputs for controls and patients were visually inspected by an expert (V.F.J.N.), and motion parameters for DTI were calculated. Outlier values (interquartile range [IQR] >1.5 above the third or below the first quartile) were calculated for fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity for each scanner, and each tract received particular attention on visual inspection. In the absence of excessive head motion or other artifact, outlier data were retained because they likely reflected true variation or pathology. One patient and 4 controls were excluded from the DTI analysis owing to artifacts.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2020, in R version 3.6.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Results are reported as median (IQR [interquartile range]) or frequency (percentage), with P values before adjustment for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was determined using a false discovery rate threshold of 5%.35 Statistical methods are outlined in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

Within-patient changes between MR1 and MR2 were compared as follows. Lesion presence was compared using the McNemar test. Because total intracranial volume is fixed, an increase in one ROI must precipitate a decrease in another. We therefore chose a compositional data analysis using an additive log ratio.36 Univariate analysis was used to identify which ROIs drove this change. For each ROI, the within-patient change was summarized in a single value as log(volume on MR2/volume on MR1), and a 2-sided, 1-sample t test was applied. An analogous analysis was performed for diffusion parameters.

Patients were compared with controls as follows. Mixed models were fitted for brain regions that changed significantly between scans. The corpus callosum was also included as commonly implicated in mTBI.37,38,39,40 Region of interest volume (normalized for total intracranial volume), fractional anisotropy, or mean diffusivity were the y variables; group (patient vs control), age, and sex, the covariates; and scanner, a random intercept.

The association between scan evolution of DTI and symptoms was assessed as follows. Change in fractional anisotropy was measured as log(fractional anisotropy at MR2/fractional anisotropy at MR1) and similarly for mean diffusivity, bringing both on the same scale. Evolution of DTI was divided into 3 phenotypes using k-means clustering. Three clusters were chosen based on biological plausibility, which correlated well with the silhouette (2 clusters) and elbow (3 clusters) methods.41 Symptom evolution was measured as the difference in RPQ (RPQ at MR2 minus RPQ at MR1) and compared between phenotypes using analysis of variance.

Logistic regression was used to examine the association between imaging findings and a favorable recovery at 3 months, defined as an extended Glasgow Outcome Scale score of 8. We dichotomized outcome for face validity (patients with mTBI should recover fully), logistic efficiency, and comparability with past studies. Covariates included the number of tracts for which fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, or both were abnormal (ie, >2 SD above [for mean diffusivity] or below [for fractional anisotropy] the mean of controls undergoing imaging on the same scanner), as well as age and sex. This binary definition was chosen to reflect vasogenic edema (mean diffusivity) and axonal loss (fractional anisotropy).42 It was chosen over a ternary categorization (low/normal/high) because it yielded better model performance and allowed inclusion of terms for “tracts with both mean diffusivity and fractional anisotropy abnormal” without resulting in multicollinarity and overfitting. Models were compared using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy on 10-fold cross-validation, the Akaike information criterion, and positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values. In a sensitivity analysis, models were fit after excluding patients with Marshall scores of 5 or 6.

Patients with missing DTI or outcome data were excluded from the respective analysis (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) because adjuvant data were insufficient for multiple imputation.43 Characteristics of patients included and excluded from each analysis were compared, and sensitivity analyses were performed (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Results

The study included 81 patients (73 CENTER-TBI and 8 local) with a median age of 45 (IQR, 24-59; range, 14-85) years, of whom 57 were male (70%) and 24 were female (30%), and 24 (30%) had a complicated mTBI with a positive initial CT finding (Table 1 and eTable 3 in the Supplement). The incidence of radiology reports with findings positive for lesions was similar at MR1 (n = 34) and MR2 (n = 31), but subarachnoid hemorrhage (9 of 14 [64%]) and intraventricular hemorrhage (8 of 10 [80%]) showed a tendency toward resolution (Table 2). None of these patients underwent neurosurgery between MR1 and MR2.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Data (n = 81)a |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) [range], y | 45 (24-59) [14-85] |

| Sex | |

| Female | 24 (30) |

| Male | 57 (70) |

| Mechanism of injury | |

| Acceleration/deceleration | 10 (12) |

| Blow to head | 7 (9) |

| Fall from height | 21 (26) |

| Ground-level fall | 19 (23) |

| Head against object | 11 (14) |

| Multimechanistic | 13 (16) |

| Glasgow Coma Score | |

| 15 | 64 (79) |

| 14 | 12 (15) |

| 13 | 5 (6) |

| Injury severity score, median (IQR) [range] | 8.5 (4.0-16.2) [1.0-41.0] |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Stratum | |

| Discharge from ED | 42 (52) |

| Admission for standard care | 30 (37) |

| ICU admission | 9 (11) |

| Recovery at 3 mob | |

| Favorable | 35 (43) |

| Unfavorable | 36 (44) |

| Missing | 10 (12) |

| Marshall score (pre-MR1) | |

| 1 | 57 (70) |

| 2 | 18 (22) |

| 3 | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 0 (0) |

| 5 | 1 (1) |

| 6 | 5 (6) |

| Time to MR1, median (IQR) [range], h | 36 (25-55) [6-72] |

| Time to MR2, median (IQR) [range], d | 17 (15-21) [9-31] |

| Time to MR3, median (IQR) [range], d | 97 (92-100) [81-120] |

| Missing | 42 (52) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; MR1, first magnetic resonance scan after injury; MR2, second magnetic resonance scan after injury; MR3, third magnetic resonance scan after injury.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (percentage) of patients.

Recovery at 3 months was considered favorable if the score on the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale was 8.

Table 2. Comparison of Lesions Visible on MR1 vs MR2a.

| Abnormality | Scan finding, No. (%) of patients | Raw P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR1 positive | MR1 negative | ||||||

| MR1 positive | MR2 | MR1 negative | MR2 | ||||

| Lesion persists | Lesion resolved | Remains negative | Shows new lesion | ||||

| Any | 34 (100) | 31 (91) | 3 (9) | 47 (100) | 47 (100) | 0 | .25 |

| Mass effect | |||||||

| Mass >25 mL | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 | 79 (100) | 79 (100) | 0 | NC |

| Midline shift | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 80 (100) | 80 (100) | 0 | NC |

| Cisternal compression | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 80 (100) | 80 (100) | 0 | NC |

| Intra-axial | |||||||

| Contusion | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 0 | 61 (100) | 61 (100) | 0 | NC |

| Traumatic axonal injury | 21 (100) | 20 (95) | 1 (5) | 60 (100) | 60 (100) | 0 | >.99 |

| Extra-axial | |||||||

| Hemorrhage | |||||||

| Epidural | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 0 | 78 (100) | 78 (100) | 0 | NC |

| Subdural | 8 (100) | 7 (88) | 1 (12) | 73 (100) | 71 (97) | 2 (3) | >.99 |

| Subarachnoid | 14 (100) | 5 (36) | 9 (64) | 67 (100) | 66 (99) | 1 (1) | .03 |

| Other | |||||||

| Skull fracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 81 (100) | 81 (100) | 0 | NC |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 10 (100) | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | 71 (100) | 71 (100) | 0 | .01 |

Abbreviations: MR1, first magnetic resonance scan after injury; MR2, second magnetic resonance scan after injury; NC, not calculated.

Eighty-one patients received a magnetic resonance scan within 72 hours (MR1) and at 2 to 3 weeks after injury (MR2). Lesions visible on the 2 scans were compared using the McNemar test for paired categorical data. Where reports were identical, no P value is shown. None of the P values was significant, assuming a 5% false discovery rate.

Volumetric Analysis

The composition of brain volume changed significantly between MR1 and MR2. This change occurred predominantly in 3 ROIs (Table 3): ventricular volume (MR2:MR1 ratio, 1.06; IQR, 1.01-1.15 [95% CI, 1.02-1.10]; P < .001) and circumferential cerebrospinal fluid volume (MR2:MR1 ratio, 1.03; IQR, 1.00-1.14 [95% CI, 1.00-1.07]; P < .001) increased, whereas cerebral white matter volume decreased (MR2:MR1 ratio, 0.98; IQR, 0.96-1.00 [95% CI, 0.96-0.99]; P = .001).

Table 3. Volumetric Changes Between MR1 and MR2a.

| ROI | ROI volume, median (IQR), cm3 | Raw P valueb | FDRc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR1 | MR2 | Absolute difference | Ratio of MR2:MR1 | |||

| Cerebrospinal fluid | ||||||

| Convexity | 1.26 (1.11 to 1.63) | 1.36 (1.13 to 1.82) | +0.05 (−0.01 to +0.18) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.14) | <.001 | Significant |

| Ventricles | 24.59 (17.52 to 33.76) | 27.00 (18.72 to 42.27) | +1.49 (+0.12 to +4.20) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.15) | <.001 | Significant |

| White matter | ||||||

| Cerebellar white matter | 16.59 (15.14 to 18.76) | 16.38 (14.57 to 18.01) | −0.39 (−1.56 to +0.47) | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.03) | .05 | NS |

| Cerebral white matter | 231.5 (215.06 to 259.48) | 229.85 (210.39 to 253.21) | −3.77 (−9.29 to −0.99) | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00) | .001 | Significant |

| Infratentorial gray matter | ||||||

| Brainstem | 29.01 (26.91 to 30.84) | 28.83 (26.46 to 30.5) | +0.08 (−0.26 to +0.43) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | .25 | NS |

| Cerebellar gray matter | 61.86 (55.94 to 66.85) | 61.82 (58.26 to 67.18) | +0.88 (−0.84 to +2.60) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.04) | .02 | NS |

| Supratentorial gray matter lobes | ||||||

| Frontal | 107.72 (97.9 to 116.55) | 108.22 (95.89 to 115.51) | +0.05 (−2.44 to +1.82) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | .36 | NS |

| Temporal | 61.62 (56.49 to 68.33) | 61.57 (57.51 to 68.64) | +0.58 (−0.51 to +1.61) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | .10 | NS |

| Parietal | 66.93 (61.77 to 71.19) | 67.36 (60.56 to 71.32) | 0.00 (−1.17 to +0.69) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | .80 | NS |

| Occipital | 42.83 (38.93 to 46.12) | 43.76 (40.37 to 46.47) | +0.18 (−0.68 to +1.57) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | .02 | NS |

| Supratentorial gray matter special regions | ||||||

| Basal ganglia | 10.48 (9.03 to 11.47) | 10.25 (9.16 to 11.26) | −0.06 (−0.32 to +0.23) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.02) | .63 | NS |

| Hippocampal complex | 8.96 (8.36 to 9.63) | 8.90 (8.27 to 9.60) | +0.03 (−0.20 to +0.22) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | .64 | NS |

| Insula | 7.19 (6.69 to 8.15) | 7.30 (6.56 to 8.12) | −0.09 (−0.23 to +0.10) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | .52 | NS |

| Thalamus | 7.89 (7.39 to 8.81) | 7.78 (7.23 to 8.61) | −0.07 (−0.44 to +0.16) | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.02) | .05 | NS |

| Other | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.15) | 0.13 (0.11 to 0.16) | +0.01 (−0.01 to +0.03) | 1.06 (0.91 to 1.28) | .02 | NS |

Abbreviations: FDR, false discovery rate; IQR, interquartile range; MR1, first magnetic resonance scan after injury; MR2, second magnetic resonance scan after injury; NS, not significant; ROI, region of interest.

Eighty-one patients with mild traumatic brain injury received a magnetic resonance scan within 72 hours of injury (MR1) and 2 to 3 weeks after injury (MR2).

Reported values are unadjusted.

Indicates which results are statistically significant using a 5% FDR threshold.

Although at MR1 these 3 ROIs did not differ significantly between patients and controls (eg, patient to control ratio for white matter volume, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97-1.01; P = .24) (eTable 4 in the Supplement), at MR2, patients had significantly larger ventricles (patient to control ratio, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32; P = .001) and smaller cerebral white matter volumes (patient to control ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-0.99; P < .001). At MR3, patients’ white matter volumes had not changed significantly from MR2 (MR3:MR2 ratio, 1.01; IQR, 1.00-1.04 [95% CI, 0.99-1.04]; P = .17) and remained low compared with controls (patient to control ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99; P = .001).

DTI Analysis

Diffusion data was available for 73 MR1 and 79 MR2 scans. Between MR1 and MR2, fractional anisotropy did not change significantly in any tract. Mean diffusivity changed significantly in 13 tracts, 12 of which displayed a decrease: the superior longitudinal fascicles I and II bilaterally, superior longitudinal fascicle III, arcuate fascicle, cingulum, middle longitudinal fascicle, thalamoprecentral tract, left striatoprecentral tract, and striatoparietal tract on the left and the right corticospinal tract. Mean diffusivity increased significantly in the left fornix.

Where patients differed significantly from controls, they had higher mean diffusivity and lower fractional anisotropy values. After correction for multiple comparisons, this imaging signature applied to the following: all assessed tracts except the left fornix (mean diffusivity at MR1); all except the right superior longitudinal fascicle I and right corpus callosum (mean diffusivity at MR2); and the left superior longitudinal fascicle I, left middle longitudinal fascicle, left striatoparietal tract, and corpus callosum (fractional anisotropy at MR1).

There was no significant within-patient difference between MR2 and MR3. However, the higher mean diffusivity values observed in patients compared with controls were no longer significant at MR3, possibly owing to the smaller number of patients available at MR3. Results of DTI for the individual 72 tracts at all points are available on request.

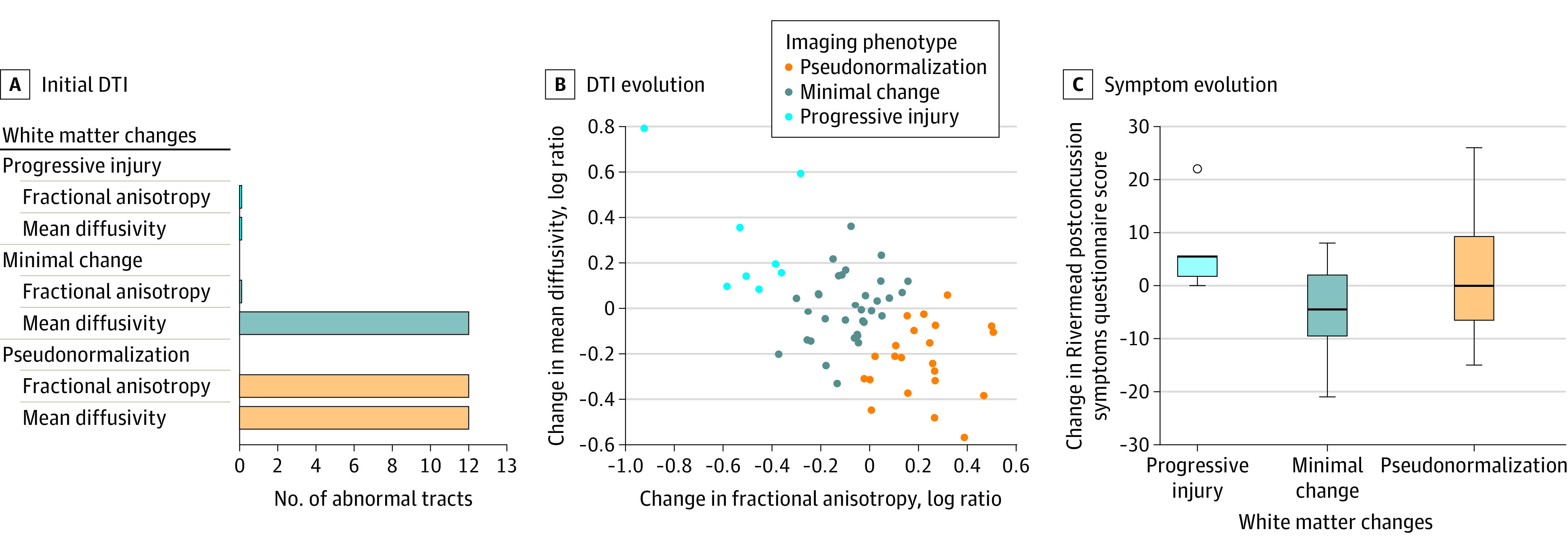

DTI Trajectories Between MR1 and MR2

Sixty-three patients had diffusion data available for all 13 tracts that changed between MR1 and MR2. These data were used to derive 3 imaging phenotypes (Figure 1B): patients with decreasing mean diffusivity and increasing fractional anisotropy (pseudonormalization), those with little change in diffusion parameters (minimal change), and those with increasing mean diffusivity and decreasing fractional anisotropy (progressive injury). These are descriptive labels, not implying an underlying mechanism.

Figure 1. Association of Imaging Results With Symptom Evolution Between Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Times.

Patients with mild traumatic brain injury received an MRI scan within 72 hours of injury (MR1) and 2 to 3 weeks after injury (MR2). The evolution of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) findings between scans was categorized into 3 phenotypes: progressive injury, minimal change, and pseudonormalization. A, DTI parameters at MR1 between patients with phenotypes and healthy controls, adjusted for age, sex, and scanner. The x-axis refers to the number of tracts with abnormal findings on MR1 of the short list of 13 tracts that were shown to change between MR1 and MR2. B, Evolution of DTI parameters between MR1 and MR2 (ie, the change in mean diffusivity vs the change in fractional anisotropy). Positive log ratios indicate an increase and negative log ratios a decrease in values between scans. C, Evolution of symptoms between scans measured as change in the score of the Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire, with positive values indicating worsening and negative values resolving symptoms. The boxes represent the interquartile range, the middle horizontal line is the median, and the whiskers extend to the largest value no farther than 1.5 IQR from the hinge.

The pseudonormalization phenotype differed from controls in both mean diffusivity and fractional anisotropy at MR1 (12 of 13 and 12 of 13 tracts had abnormal findings, respectively) but normalized on MR2 (0 of 13 and 0 of 13 tracts had abnormal findings, respectively). In the minimal change phenotype, mean diffusivity but not fractional anisotropy differed from controls at MR1 (12 of 13 and 0 of 13 tracts had abnormal findings, respectively), and this diffusivity persisted at MR2 (6 of 13 and 0 of 13 tracts had abnormal findings, respectively). Interestingly, the progressive injury phenotype, despite showing within-patient deterioration of diffusion parameters, did not, as a group, differ significantly from controls at either scan.

Symptom Trajectories Between MR1 and MR2

Baseline RPQ scores did not differ among image-based phenotypes (9.00 [IQR, 7.50-18.00] for pseudonormalization; 12.00 [IQR, 8.00-20.75] for minimal change; and 10.00 [IQR, 2.75-18.75] for progressive injury; P = .75). Symptom evolution, however, was significantly associated with phenotypes (Figure 1C), even after sensitivity analysis (eTable 5 in the Supplement). The RPQ scores deteriorated in the progressive injury phenotype (+5.00 [IQR, +2.00 to +5.00]), improved in the minimal change phenotype (−4.50 [IQR, −9.25 to +1.75]), and showed a variable evolution in the pseudonormalization phenotype (0.00 [IQR, −6.25 to +9.00]) (P = .02).

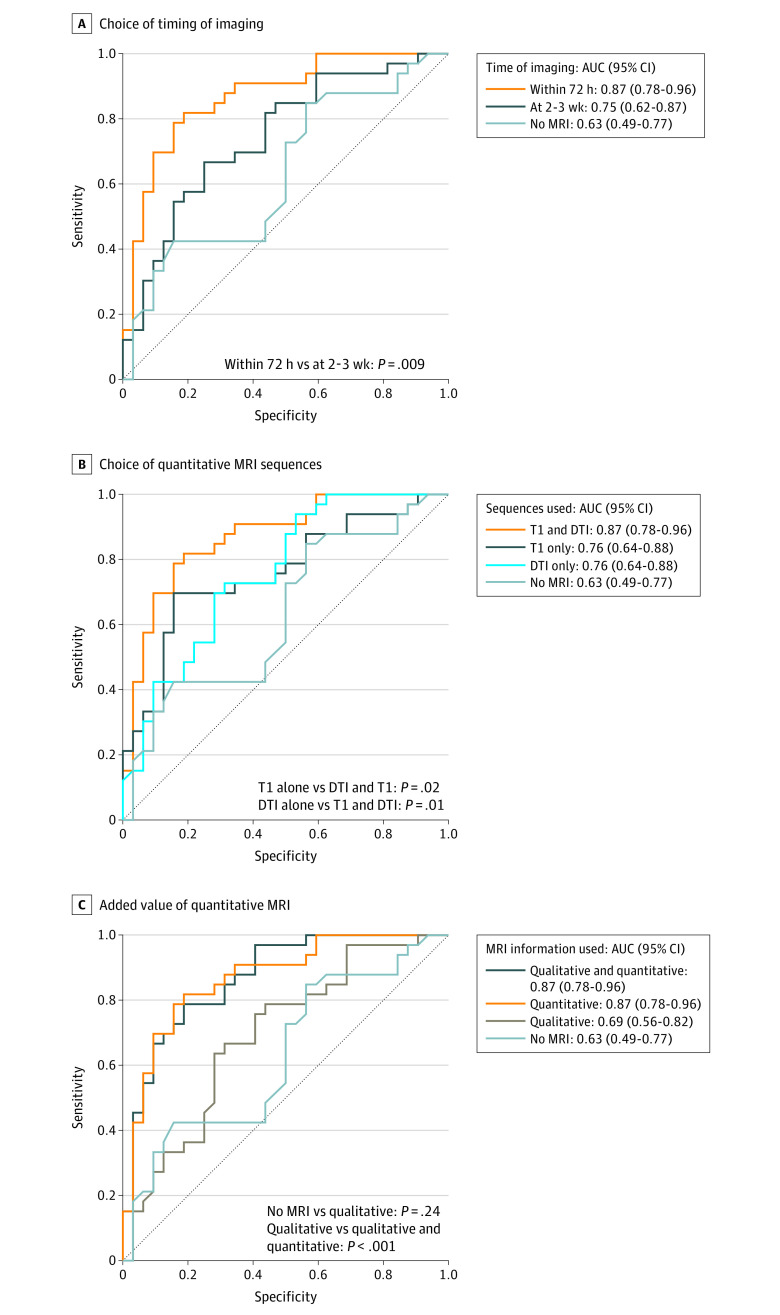

Outcome Analysis

Recovery was favorable for 33 of 65 patients (51%) at 3 months. The association between recovery and imaging findings was significantly closer at MR1 than at MR2 (AUC, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.78-0.96] vs 0.75 [95% CI, 0.62-0.87; P = .009]; PPV, 0.79 vs 0.69; and NPV, 0.81 vs 0.67) (Figure 2A). Combining both sequences at MR1 (results above) was superior to using T1 weighting (AUC, 0.76 [95% CI, 0.64-0.88; P = .02]; PPV, 0.81; and NPV, 0.71) or DTI (AUC, 0.76 [95% CI, 0.64-0.88; P = .01]; PPV, 0.62; and NPV, 0.65) alone (Figure 2B). Quantitative imaging added value beyond the visible lesion presence (AUC, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.78-0.96] vs 0.69 [95% CI, 0.56-0.82; P < .001]; PPV, 0.72 vs 0.68; and NPV, 0.76 vs 0.65) (Figure 2C). All results were robust to sensitivity analyses (eTables 6 and 7 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Estimation of Recovery at 3 Months Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

Logistic regression was used to associate imaging with the odds of a favorable recovery at 3 months after injury, defined as a score on the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale of 8. The no-MRI model includes only age and sex. All other models contain age and sex plus imaging information. A, Models using imaging information obtained at 72 hours or 2 to 3 weeks after injury are compared. Imaging information includes both quantitative sequences (structural sequence [T1-weighted] and diffusion tensor imaging [DTI]). B, Imaging sequences obtained within 72 hours were compared. For T1, the variable used was the deviation of the patients’ cerebral white matter volume from that of healthy controls undergoing scanning on the same machine, whereby the volumes were normalized to each participant’s total intracranial volume. For DTI, variables included the number of tracts with abnormal findings with regard to fractional anisotropy, median diffusivity, or both compared with healthy controls undergoing scanning on the same machine. C, The added value of quantitative (T1-weighted and DTI) beyond qualitative information, that is, the presence or absence of any visible lesion reported by an expert who reviewed all available sequences (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and susceptibility-weighted imaging and DTI) is compared. AUC indicates area under the curve with 95% CI. P values were calculated using a paired DeLong test for comparing AUCs.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest analysis to date of patients with mTBI undergoing serial MRI within the first few weeks after injury44,45,46,47 and the first of those analyses to include multiple centers. Our data document the dynamic evolution of both conventional and advanced MRI (using DTI), with the earlier point (<72 hours) showing potential prognostic value.

Regarding conventional MRI, a longitudinal study found traumatic lesions in 12% of patients with mTBI within 72 hours, half of which were consistent with traumatic axonal injury.10 Similar to our findings, traumatic axonal injury and subarachnoid hemorrhage remained visible on later scans; however, intraventricular hemorrhage was not reported. Although no intervention was needed for subarachnoid hemorrhage and intraventricular hemorrhage, these lesions have prognostic significance in moderate to severe TBI17 and may help select enriched populations for clinical follow-up or interventional trials also in mTBI.

The reduction in white matter volume between MR1 and MR2 could either be ascribed to resolution of early edema or to late loss of white matter. Compared with controls, patients had similar volumes at MR1 but reduced volumes at MR2. This finding suggests that the reduction of white matter volume at MR2 (which persisted at MR3) did not represent resolution of edema but rather new, persistent, and potentially progressive pathology (eg, Wallerian degeneration).48 Similarly, a study of 14 patients with mTBI46 found an enlargement of ventricles and cerebrospinal fluid volume between 72 hours and 1 month using voxel-based morphometry.

Limited literature is available on ultra-early DTI in mTBI. A longitudinal study of 25 patients detected widespread reductions in fractional anisotropy compared with controls at 72 hours and 3 months.12 In football players (n = 26) undergoing imaging 24 hours after a concussion, mean diffusivity was decreased compared with that of controls bilaterally in several regions and remained low at 8 days.44 Interestingly, within individuals, imaging findings did not change. Although a small study of 20 patients with mTBI detected within-patient changes in fractional anisotropy within that first week after injury,47 this outcome may suggest that markers of injury progression/resolution become visible closer to the 2- to 3-week point used in the present study. Supporting this notion, a study of 33 patients undergoing imaging within 7 days after injury found reductions in fractional anisotropy, which partially recovered at 1 and 3 months.45 Similarly, the aforementioned study of imaging in 14 patients with mTBI at 72 hours and 1 month reported a fall in mean diffusivity and a rise in fractional anisotropy between scans.46 Values remained abnormal compared with those of controls at both points.46 A comparison of various MRI modalities in 62 patients with mTBI within 24 hours of injury found that only DTI was sensitive enough to detect changes relative to orthopedic controls.49 We also found that abnormalities are demonstrable within 72 hours using DTI. Importantly, abnormalities are detectable even when conventional imaging results are normal. Although these abnormalities evolve within the first month of injury, they persist at 3 months.

In addition to replicating past results, we have, for the first time to our knowledge, parsed MRI and DTI changes in mTBI by deriving clinically plausible imaging phenotypes that were associated with symptom trajectories. Such diversity in the host response to injury may explain why past studies, which assumed a uniform response among all patients, do not always agree on the direction or magnitude of DTI changes. Previous studies considered diffusion parameters in isolation rather than the interaction of fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity, which may further explain inconsistent results when trying to determine the association between DTI abnormalities and early mTBI symptoms.45,47,50 We noted that patients with progressive changes in their DTI metrics had worsening RPQ scores, which agrees with previous work in moderate to severe TBI.13

Perhaps most importantly, the earliest imaging time point (<72 hours) but less so the second (2-3 weeks) showed good prognostic value. A previous study12 (n = 25) found no difference on ultra-early DTI between patients with and without persistent postconcussional symptoms. That analysis, however, only examined individual tracts, whereas we derived a whole-brain measure of DTI derangement to better account for the heterogeneity of injury location. Consistent with our approach, a study in which 76 patients underwent imaging 5 to 18 days after injury found an association between outcome and having at least 1 abnormal white matter ROI (defined as fractional anisotropy >2.2 SDs below the control mean).11 Our data suggest that the earlier the MRI, the closer the association with outcome after mTBI. However, the pattern of white matter injury likely varies between individuals owing to both injury and host factors. Better detection of injury (eg, with multishell diffusion MRI), refined analysis with smaller ROIs, more complex models for outcome prediction (eg, using machine learning), and larger patient numbers may all refine the role of MRI in general and ultra-early MRI in particular.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this multicenter study include use of clinical scanners (not only research-dedicated ones), which provided a more generalizable assessment of the magnitude of changes detectable in clinical practice. This study also has some limitations. Although our sample size of 81 patients compares well with past serial studies of ultra-early imaging, future studies will need larger numbers to allow external validation of our findings before translation into clinical practice. Larger numbers would also allow for the inclusion of additional covariates in the outcome models, such as Marshall score, extracranial injury, or prior mental health, to better understand what MRI adds beyond currently available clinical information. Future studies may also benefit from extra time points to refine the optimal timing for MRI. In addition, more sensitive outcome measures are required to determine whether MRI could further differentiate between those patients who fully recovered and those with persistent, albeit nondisabling, symptoms (both extended Glasgow Outcome Scale scores of 8).

Conclusions

In this cohort study, acute mTBI symptoms as well as longer-term functional outcome were associated with white matter changes detectable on advanced MRI. Imaging may thus document the evolution of pathology, thereby highlighting windows for therapy. In addition, imaging can provide prognostic information to help select patients for clinical follow-up or interventional trials. Importantly, our findings demonstrate that MRI appearances are dynamic and that images obtained closer to the time of injury are more strongly associated with outcome. Future studies with more patients and time points will help to further establish the optimal timing and clinical utility of MRI after mTBI.

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Patients Included in the Analysis

eTable 1. Overview of Statistical Methods

eTable 2. Comparison of Patients With and Without Data Available for Each Analysis

eTable 3. Comparison of Lesions Visible on CT vs MR1

eTable 4. Comparison of Volumes Between Patients and Controls

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis of Symptom Evolution

eTable 6. Components of the Outcome Models

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analysis of Outcome Models

eFigure 2. Analysis With and Without Patients Who Have Mass Lesions on CT

References

- 1.Maas AIR, Menon DK, Adelson PD, et al. ; InTBIR Participants and Investigators . Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(12):987-1048. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30371-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steyerberg EW, Wiegers E, Sewalt C, et al. ; CENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators . Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in CENTER-TBI: a European prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(10):923-934. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30232-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Naalt J, Timmerman ME, de Koning ME, et al. Early predictors of outcome after mild traumatic brain injury (UPFRONT): an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(7):532-540. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30117-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuben A, Sampson P, Harris AR, Williams H, Yates P. Postconcussion syndrome (PCS) in the emergency department: predicting and pre-empting persistent symptoms following a mild traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(1):72-77. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson LD, Temkin NR, Dikmen S, et al. ; TRACK-TBI Investigators . Recovery after mild traumatic brain injury in patients presenting to US level I trauma centers: a Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) study. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(9):1049-1059. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theadom A, Barker-Collo S, Jones K, et al. ; BIONIC4you Research Group . Work limitations 4 years after mild traumatic brain injury: a cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(8):1560-1566. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nygren-de Boussard C, Holm LW, Cancelliere C, et al. Nonsurgical interventions after mild traumatic brain injury: a systematic review: results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(3)(suppl):S257-S264. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuh EL, Mukherjee P, Lingsma HF, et al. ; TRACK-TBI Investigators . Magnetic resonance imaging improves 3-month outcome prediction in mild traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(2):224-235. doi: 10.1002/ana.23783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yue JK, Winkler EA, Puffer RC, et al. ; the TRACK-TBI Investigators . Temporal lobe contusions on computed tomography are associated with impaired 6-month functional recovery after mild traumatic brain injury: a TRACK-TBI study. Neurol Res. 2018;40(11):972-981. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2018.1505416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Einarsen CE, Moen KG, Håberg AK, et al. Patients with mild traumatic brain injury recruited from both hospital and primary care settings: a controlled longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(22):3172-3182. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuh EL, Cooper SR, Mukherjee P, et al. ; TRACK-TBI Investigators . Diffusion tensor imaging for outcome prediction in mild traumatic brain injury: a TRACK-TBI study. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(17):1457-1477. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlsen RH, Einarsen C, Moe HK, et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging in mild traumatic brain injury and postconcussional syndrome. J Neurosci Res. 2019;97(5):568-581. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newcombe VFJ, Correia MM, Ledig C, et al. Dynamic changes in white matter abnormalities correlate with late improvement and deterioration following TBI: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30(1):49-62. doi: 10.1177/1545968315584004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodd AB, Epstein K, Ling JM, Mayer AR. Diffusion tensor imaging findings in semi-acute mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(14):1235-1248. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korley FK, Peacock WF, Eckner JT, et al. Clinical gestalt for early prediction of delayed functional and symptomatic recovery from mild traumatic brain injury is inadequate. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(12):1384-1387. doi: 10.1111/acem.13844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perel P, Arango M, Clayton T, et al. ; MRC CRASH Trial Collaborators . Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336(7641):425-429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39461.643438.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008;5(8):e165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverberg ND, Gardner AJ, Brubacher JR, Panenka WJ, Li JJ, Iverson GL. Systematic review of multivariable prognostic models for mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(8):517-526. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikolić A, Polinder S, Steyerberg EW, et al. ; Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) Study Participants and Investigators . Prediction of global functional outcome and post-concussive symptoms after mild traumatic brain injury: external validation of prognostic models in the Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) Study. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(2):196-209. doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maas AIR, Menon DK, Steyerberg EW, et al. ; CENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators . Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI): a prospective longitudinal observational study. Neurosurgery. 2015;76(1):67-80. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CENTER-TBI. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02210221. Updated January 26, 2021. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02210221

- 22.Lunter CM, Carroll EL, Housden C, et al. Neurocognitive testing in the emergency department: a potential assessment tool for mild traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2019;31(3):355-361. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veenith TV, Carter E, Grossac J, et al. Inter subject variability and reproducibility of diffusion tensor imaging within and between different imaging sessions. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King NS, Crawford S, Wenden FJ, Moss NEG, Wade DT. The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. J Neurol. 1995;242(9):587-592. doi: 10.1007/BF00868811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson JTL, Pettigrew LEL, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15(8):573-585. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veenith TV, Carter EL, Grossac J, et al. Use of diffusion tensor imaging to assess the impact of normobaric hyperoxia within at-risk pericontusional tissue after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(10):1622-1627. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vande Vyvere T, Wilms G, Claes L, et al. ; Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) Investigators and Participants . Central versus local radiological reading of acute computed tomography characteristics in multi-center traumatic brain injury research. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(7):1080-1092. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledig C, Heckemann RA, Hammers A, et al. Robust whole-brain segmentation: application to traumatic brain injury. Med Image Anal. 2015;21(1):40-58. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manjón JV, Coupé P, Concha L, Buades A, Collins DL, Robles M. Diffusion weighted image denoising using overcomplete local PCA. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veraart J, Novikov DS, Christiaens D, Ades-Aron B, Sijbers J, Fieremans E. Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. Neuroimage. 2016;142:394-406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veraart J, Fieremans E, Jelescu IO, Knoll F, Novikov DS. Gibbs ringing in diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76(1):301-314. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1063-1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeurissen B, Tournier JD, Dhollander T, Connelly A, Sijbers J. Multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution for improved analysis of multi-shell diffusion MRI data. Neuroimage. 2014;103:411-426. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasserthal J, Neher P, Maier-Hein KH. TractSeg—fast and accurate white matter tract segmentation. Neuroimage. 2018;183:239-253. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.07.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57(1):289-300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aitchison J. A concise guide to compositional data analysis. 2nd Compositional Data Analysis Workshop. Published 2005. Accessed May 31, 2019. http://ima.udg.edu/Activitats/CoDaWork05/A_concise_guide_to_compositional_data_analysis.pdf

- 37.Wang Z, Zhang M, Sun C, et al. Single mild traumatic brain injury deteriorates progressive inter-hemispheric functional and structural connectivity. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(4):464-473. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grover H, Qian Y, Boada FE, Lakshmanan K, Flanagan S, Lui YW. MRI evidence of altered callosal sodium in mild traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(12):2200-2204. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunter LE, Lubin N, Glassman NR, Xue X, Spira M, Lipton ML. Comparing region of interest versus voxel-wise diffusion tensor imaging analytic methods in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(8):1222-1230. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallace EJ, Mathias JL, Ward L. Diffusion tensor imaging changes following mild, moderate and severe adult traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(6):1607-1621. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9823-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kassambara A. Determining the optimal number of clusters: 3 must know methods—Datanovia. Published 2018. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://www.datanovia.com/en/lessons/determining-the-optimal-number-of-clusters-3-must-know-methods/#elbow-method

- 42.Hutchinson EB, Schwerin SC, Avram AV, Juliano SL, Pierpaoli C. Diffusion MRI and the detection of alterations following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2018;96(4):612-625. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richter S, Stevenson S, Newman T, et al. Handling of missing outcome data in traumatic brain injury research: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(19):2743-2752. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lancaster MA, Olson DV, McCrea MA, Nelson LD, LaRoche AA, Muftuler LT. Acute white matter changes following sport-related concussion: a serial diffusion tensor and diffusion kurtosis tensor imaging study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(11):3821-3834. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin B, Li DD, Huang H, et al. Longitudinal changes in diffusion tensor imaging following mild traumatic brain injury and correlation with outcome. Front Neural Circuits. 2019;13:28. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2019.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toth A, Kovacs N, Perlaki G, et al. Multi-modal magnetic resonance imaging in the acute and sub-acute phase of mild traumatic brain injury: can we see the difference? J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(1):2-10. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas AW, Watts R, Filippi CG, et al. Dynamic changes in diffusion measures improve sensitivity in identifying patients with mild traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill CS, Coleman MP, Menon DK. Traumatic axonal injury: mechanisms and translational opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39(5):311-324. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Narayana PA, Yu X, Hasan KM, et al. Multi-modal MRI of mild traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;7:87-97. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mustafi SM, Harezlak J, Koch KM, et al. Acute white-matter abnormalities in sports-related concussion: a diffusion tensor imaging study from the NCAA-DoD CARE Consortium. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(22):2653-2664. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Patients Included in the Analysis

eTable 1. Overview of Statistical Methods

eTable 2. Comparison of Patients With and Without Data Available for Each Analysis

eTable 3. Comparison of Lesions Visible on CT vs MR1

eTable 4. Comparison of Volumes Between Patients and Controls

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis of Symptom Evolution

eTable 6. Components of the Outcome Models

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analysis of Outcome Models

eFigure 2. Analysis With and Without Patients Who Have Mass Lesions on CT