Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: High recurrence rates and early recurrence have been reported for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) involving the skull base. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced CT scanning for the detection of residual disease (RD) in the early postoperative course after surgical excision of JNA.

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed data in 20 male patients (mean age ± SD, 15.4 ± 5 years; range, 10–32 years) who underwent enhanced helical CT in the days after apparent complete surgical excision of JNA with initial expansion in the skull base. Four independent, blinded readers evaluated the occurrence of RD. Final diagnoses were rendered on the basis of histologic examination of excised specimens of RD or clinical and radiologic follow-up. The Cohen κ test was performed to examine interreader agreement.

RESULTS: Postoperative contrast-enhanced CT had a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 83%, a positive predictive value of 75% and a negative predictive value of 83% for the detection of RD. The prevalence of RD was 40%. The base of pterygoids was the most frequent location of RD. Interreader agreement was high for the detection of putative RD (κ = 0.83). Variabilities in readers’ interpretations were encountered for false-positive results and for disease in the foramen lacerum. False-negative results involved the base of pterygoids. Early postoperative CT scanning was well tolerated by all patients.

CONCLUSION: Contrast-enhanced helical CT is an accurate tool to evaluate excision of JNA in the days after surgery.

Contrast-enhanced CT scanning and MR imaging are valuable imaging modalities in the work-up of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) (1). Basically, the tumor originates from the sphenopalatine foramen and involves both the pterygopalatine fossa and the posterior nasal cavity (2, 3). JNA develops through certain paths of extension (3–5), expanding by means of bony erosion and displacement of adjacent structures, with possible expansion in the skull base.

Surgery remains the criterion standard for the treatment of JNA (3–7). Despite new advancements in surgery, high recurrence rates and early recurrence have been reported, especially when the JNA involves the skull base (3–5). More frequent recurrences are correlated with the extension of JNA at the skull base, in areas such as the sphenoid sinus, the base of the pterygoids and clivus, and the cavernous sinus and anterior fossa (3–5). A mean recurrence rate of 32% to as high as 40–50% in the case of skull base invasion has been reported (3, 4, 8–12).

Recurrence is growth of residual disease (RD). Total removal of JNA is difficult when invasion of the skull base occurs (3). Some tumor may be left in place even when the resection is deemed complete, leading to unidentified RD. Early detection of such RD may allow for treatment and thus a reduction of recurrences. To our knowledge, this important issue has not been raised in the early postoperative course of surgical excision of JNA. In our institution, we have developed a specific protocol that uses helical CT to detect RD in the days following surgery; the purpose is to treat RD as early as possible.

The choice between contrast-enhanced CT and MR imaging to identify RD is open to debate. Both MR imaging and enhanced CT provide a good definition of the soft tissue interactions and the extent of JNA. We chose contrast-enhanced CT because it depicts the close interactions between the bony anatomy and RD. In addition, helical CT is less prone to motion artifact.

The purpose of the present retrospective study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced CT to detect RD in the days after surgical excision of JNA that has expanded in the skull base.

Methods

Cohort

We retrospectively reviewed data from 20 male patients with histologically proved JNA that was treated in our department between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2001. Patients had a minimum of 2 years of follow-up and had undergone contrast-enhanced helical CT in the days after apparently complete surgical excision of JNA that eroded the skull base. They were aged 10–32 years, with an average age ± SD of 15.4 ± 5 years. All patients underwent a radiologic evaluation and procedure, surgical excision of JNA, and early postoperative CT. Follow-up ranged from 24 to 76 months, with a median of 42 months.

In all patients, the extent of the tumor was preoperatively assessed by means of CT scanning and MR imaging when available. The radiologic evaluation of tumoral extent has been previously reported (4). Table 1 lists the extension and stages of the tumors in our patients. All 20 had stage III disease (i.e., tumor with erosion of the skull base) according to the classification by Radkowski et al (10). Seventeen patients had stage IIIA disease, with erosion of the skull base and minimally intracranial extension corresponding to erosion of the foramen ovale and foramen rotondum or the base of pterygoids and clivus. Three patients had stage IIIB tumor corresponding to extensive intracranial extension.

TABLE 1:

Tumor extension and stage

| Patient | Location of Extension* |

Stage | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIB | ||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | |||||||||||

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | |||||||||||

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | |||||||||

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | |||||||||||||

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIB | ||||||||

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||||

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | |||||||||

| 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||||

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||

| 17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | |||||||||||

| 18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||||||

| 19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIA | ||||||||||||

| 20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IIIB | ||||||||

Preoperative CT scans were examined for 18 locations of tumor extension, as follows: 1 indicates present; 2, pterygopalatine fossa; 3, inferior orbital fissure; 4, orbital apex; 5, cavernous sinus (anterior); 6, infratemporal fossa; 7, temporal fossa; 8, interpterygoid fossa; 9, paratubal region; 10, foramen ovale and foramen rotondum; 11, cavernous sinus (lateral); 12, parapharyngeal space; 13, sphenoid sinus; 14, base of pterygoids and clivus; 15, cavernous sinus (medial); 16, foramen lacerum; 17, optic canal; and 18, anterior fossa.

Diagnosis and embolization angiographic procedures had been performed in every case (13, 14). An interventional radiologists (R.C.) embolized the tumor by using 100–1000-μm particles (Embospheres, Biosphere Medical, Inc., Rockland, MA; Ivalon PVA, Ivalon Inc., San Diego, CA; and TRUFILL n-Butyl Cyanocrylate [n-BCA], Cordis Neurovascular Inc., Miami Lakes, FL) after superselective catheterization of the supplying tumor branches from the external carotid artery was done. When the vascular supply originating from the internal carotid artery, embolization was achieved by direct puncture of JNA and in situ injection of adhesive mixed with a contrast agent (nCBA, Histoacryl, B. Braun Medical Inc., Sheffield, England) during temporary exclusion of the internal carotid artery (three patients). Total tumor devascularization was achieved in 11 patients, and devascularization greater than 90% was obtained in nine patients. No embolization complications occurred.

The patients underwent surgical excision of the tumor 24–48 hours after embolization. A transfacial approach was used by means of midfacial degloving (eight patients) or lateral rhinotomy (two patients). A transnasal endoscopic approach was combined with a transfacial approach in three patients. A neurosurgical approach (pterional) was performed in two patients, with an endoscopic-assisted technique to remove the JNA. A purely transnasal endoscopic approach was used in eight patients. Piecemeal removal of the tumors was performed owing to preoperative embolization. The base of pterygoids and the basisphenoid were drilled out in 11 of 20 patients (5). At the end of the surgical procedure, a hemostatic agent was used to line the surgical cavity (Surgicel; Ethicon, Piscataway, NJ) in combination with nasal packing (Netcell, Network Medical Products Ltd, Tyne and Wear, England). The packing was removed before postoperative CT scanning was done.

Postoperative CT Technique

Postoperative contrast-enhanced helical CT was performed with a multidetector-row scanner (TwinFlash; Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). Tube current and voltage were 200 mA and 120 kV, respectively. A 512 × 512 matrix was used, and the field of view was 24 cm. Scanning extended from the frontal sinus to the inferior limit of the oropharynx (vallecula). Conventional scanning techniques were used, with a 1.3-mm section thickness every 0.7 mm and a pitch of 1. Images were reconstructed every 2.5 mm in the coronal and axial planes by using a digital workstation (MX VIEW, Philips Medical Systems). All coronal reconstructions were obtained from axial data. The average scanning duration was approximately 60 seconds. Each patient received a total of 90 mL of nonionic contrast agent (Xenetix 350; Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France) at a uniphase flow rate of 1.5 mL/s. The contrast material was administered by means of a power injector (Medrad, Indianola, PA) through an intravenous cannula placed in an antecubital vein. Scanning started after a lag time of 50 seconds after the start of the injection.

Image Analysis

Four investigators (R.E.K., J.P.G., R.C., P.H.) reviewed the CT scans in a blinded, retrospective manner. The readers evaluated the images independently. The reading order was randomized, and preoperative images were available for each reader. No clinical information was given with the images. RD was suspected when a persistent tumor was seen at a place corresponding to the initial extension of the tumor. Signs of RD were characterized by positive enhancement or the presence of contrast agent (nCBA) in a site of initial JNA extension. The readers rated the presence or absence of RD on a three-point scale as follows: 1 was absent; 2, “do not know,” and 3, present. The presence or absence of RD was established according to the final diagnoses of RD, which were rendered on the basis of histologic examination of excised specimens of the RD or clinical and radiologic follow-up.

When RD was detected on a CT scan, subsequent surgical exploration was done with the intent to treat. Minimally invasive surgery through an endoscopic approach was performed. RD was removed and confirmed or ruled out on histologic examination. If RD was confirmed, the result of the early postoperative CT was considered true-positive. If the RD was not confirmed, the CT result was considered false-positive. When no RD was detected on the early postoperative CT, the patient underwent follow-up according to the standard protocol at our institution. Six months after original surgery, patients underwent endoscopic examination at an outpatient visit and enhanced CT scanning. The patients were then followed up with regular endoscopic examinations and CT studies. In the case of normal CT scans without recurrence, the result of early postoperative CT was considered true-negative. In the case of recurrence, the result was considered false-negative. All the patients were followed up according to the aforementioned standard protocol at our institution.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were carried out by using STATA 8.0 for Windows (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Our report was specifically designed to analyze the diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced CT for the detection of RD. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of early postoperative CT, as well as the prevalence of RD, were analyzed for each reader and then pooled according to the previous results (true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, false-negative). The Cohen κ test was performed to examine interreader agreement. For sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by using nonparametric bootstrap resampling. Statistical significance was set at the level of .05.

Results

Postoperative CT

Early postoperative CT was well tolerated by all patients. No complications or adverse events occurred after the injection of contrast agent in the early postoperative course. Enhanced helical CT was performed within 2.8 ± 1.8 postoperative days. The mean size of RD was 0.95 ± 0.3 cm.

Image Analysis

Table 2 summarizes the results of early postoperative CT scanning. RD was suspected in eight patients and not in the other 12. Among the eight instances of RD identified, six were confirmed at revision surgery (true-positive) and two were not (false-positive, patients 3 and 16). Among the 12 patients without RD on early CT, two had tumor recurrence (false-negative, patients 11 and 20). These findings resulted in a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 83%, PPV of 75%, and NPV of 83%. The prevalence of RD was 40%.

TABLE 2:

Results of postoperative CT according to surgical results and outcome

| Patient | Postoperative CT |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Result* | Location of RD† | |

| 1 | 3 | TN | |

| 2 | 4 | TP | 5, 8 |

| 3 | 1 | FP | 13 |

| 4 | 5 | TN | |

| 5 | 5 | TP | 16 |

| 6 | 3 | TN | |

| 7 | 2 | TN | |

| 8 | 2 | TN | |

| 9 | 2 | TP | 2, 14 |

| 10 | 1 | TP | 8 |

| 11 | 2 | FN | 14 |

| 12 | 4 | TN | |

| 13 | 4 | TN | |

| 14 | 2 | TP | 14 |

| 15 | 5 | TN | |

| 16 | 1 | FP | 14 |

| 17 | 1 | TN | |

| 18 | 1 | TN | |

| 19 | 1 | TP | 6, 14 |

| 20 | 2 | FN | 14 |

FN indicates false-negative; FP, false-positive; TN, true-negative; and TP, true-positive.

RD locations are listed according to 18 locations of tumor extension; 1 is nasopharyngeal vault; 2, pterygopalatine fossa; 3, inferior orbital fissure; 4, orbital apex; 5, cavernous sinus (anterior); 6, infratemporal fossa; 7, temporal fossa; 8, interpterygoid fossa; 9, paratubal region; 10, foramen ovale and foramen rotondum; 11, cavernous sinus (lateral); 12, parapharyngeal space; 13, sphenoid sinus; 14, base of pterygoids and clivus; 15, cavernous sinus (medial); 16, foramen lacerum; 17, optic canal; and 18, anterior fossa.

True-Negative Results.—

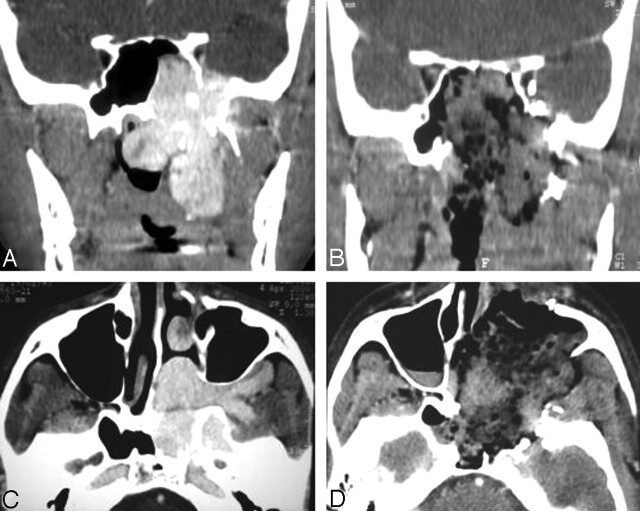

Figure 1 depicts the normal aspect of early postoperative CT when no RD was identified (true-negative). No tumor was distinguishable in the locations where the initial JNA had extended before surgery. Sparse material, such as hemostatic agents mixed with blood, could be detected in the operative cavity.

Fig 1.

True-negative result on CT scans.

A and C, Preoperative coronal (A) and axial (C) images show JNA.

B and D, Postoperative enhanced coronal (B) and axial (D) images illustrate a normal aspect of early postoperative CT when no RD is identified. There is no enhancement at the preoperative location of JNA. Hemostatic material mixed with blood is seen in the postoperative cavity.

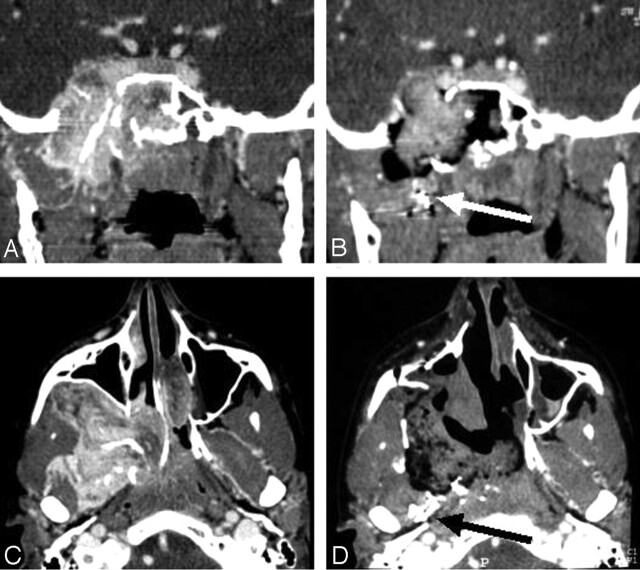

True-Positive Results.—

Figure 2 shows an early postoperative CT scan displaying RD, which was confirmed after revision surgery (true-positive). The base of the pterygoids and the clivus were the most frequent locations of RD (Table 3).

Fig 2.

True-positive result. Early postoperative enhanced helical CT reveals RD.

A and B, Coronal (A) and axial (B) images of show RD on the lateral edge of the pterygoids (arrow).

C and D, Coronal (C) and axial (D) images show RD in the pterygoid muscles (arrows).

E and F, Coronal (E) and axial (F) images show RD in the foramen lacerum (arrow).

TABLE 3:

Locations of RD at early enhanced CT after surgical excision of JNA

| Location | No. of Observations |

|---|---|

| Pterygopalatine fossa | 1 |

| Cavernous sinus (anterior) | 1 |

| Interpterygoid fossa | 2 |

| Base of pterygoids and clivus | 3 |

| Foramen lacerum | 1 |

Note.—Several locations could have been involved in the same RD.

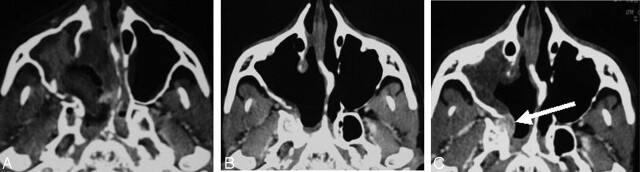

False-Positive Results.—

Two patients had suspected RD: one case in the sphenoid sinus (patient 3) and the other, at the base of pterygoids (patient 16). Revision surgery did not reveal RD (false-positive). In patient 16, nCBA adhesive material was thought to persist at the location of initial JNA extensions (Fig 3). Normal tissue containing embolization material was found on pathologic examination. Neither of these patients developed a recurrence in the areas of concern after 18 or 24 months of follow-up.

Fig 3.

False-positive result. Suspected RD at the base of the pterygoids.

A and C, Preoperative coronal (A) and axial (C) CT scans show JNA.

B and D, Early postoperative coronal (B) and axial (D) CT scans show persistent contrast with adhesive material (arrow) at the location of the initial JNA extensions. No RD was found after surgical revision.

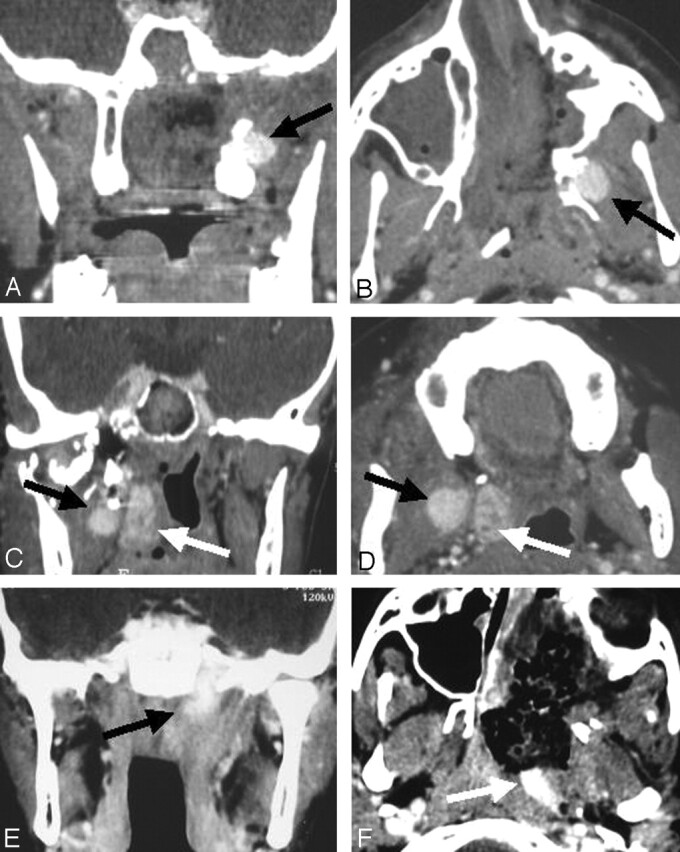

False-Negative Results.—

Two patients had tumoral recurrence, which appeared during follow-up at 20 or 24 months after initial surgery (Fig 4). Both recurrences were located in the base of the pterygoids and suspected to be intraosseous. The bony location might have explained why the early postoperative contrast-enhanced helical CT scan had not depicted them.

Fig 4.

False-negative result. Axial CT scans.

A and B, Early postoperative (A) and 6-month (B) images show no evidence of RD.

C, At 24 months after original surgery, scan shows recurrence of JNA at the base of the pterygoids (arrow).

Pooled Results

When the results of the various readers were pooled, the ratings indicated a sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 94%, PPV of 90%, and NPV of 83%. The mean prevalence of RD was 41%.

Interreader Variability

Interreader agreement was high for the detection of RD (κ = 0.83). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV, as well as prevalence, are given in Table 4 according to each reader’s interpretations. Separate analysis of RD detection by the readers indicated slightly higher scores for reader 2. Greater variability in readers’ interpretations were encountered for false-positive results and involvement of the foramen lacerum.

TABLE 4:

Detection of RD on early enhanced CT after surgical excision of JNA

| Parameter | Reader 1 |

Reader 2 |

Reader 3 |

Reader 4 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 95% CI | Value | 95% CI | Value | 95% CI | Value | 95% CI | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 71 | 31, 99 | 75 | 34, 97 | 75 | 34, 97 | 75 | 40, 97 |

| Specificity (%) | 91 | 67, 98 | 100 | 72, 100 | 100 | 72, 100 | 83 | 59, 99 |

| PPV (%) | 83 | 50, 97 | 100 | 54, 100 | 100 | 54, 100 | 75 | 47, 99 |

| NPV (%) | 83 | 52, 98 | 83 | 53, 98 | 83 | 53, 98 | 83 | 52, 98 |

| Prevalence (%) | 39 | 17, 64 | 42 | 20, 66 | 42 | 20, 66 | 40 | 18, 67 |

Note.—If a reader responded “do not know” (four choices in three patients, or 80 choices [5%]), the choice was excluded in the calculation of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV, but it was taken into account for the calculation of interreader agreement.

Discussion

The present results demonstrate that the contrast-enhanced helical CT enabled the detection of RD in the early postoperative course after JNA involving the skull base was excise. Early postoperative scans had higher specificity (83%) than sensitivity (75%) and higher NPV (83%) than PPV (75%). The range of 95% CIs for the results was wide because of the small number of patients, which reflects the rare occurrence of the disease. The high κ values indicate high interreader consistency in the early detection of RD with CT (15).

When CT depicts RD, the finding should reliably correspond to a true RD at revision surgery. The specificity (83%) and PPV (75%) of early postoperative CT scan was relatively high. Therefore, contrast-enhanced CT may have diagnostic value, as it had relatively high accuracy in the diagnosis of RD while creating minimal patient discomfort.

The sensitivities and NPVs suggest that a patent RD can be detected in most cases. Potential RD may be missed during postoperative CT scan in two circumstances: First, the size and attenuation of the RD may be overlooked. The location of recurrences is reportedly correlated with certain extension paths of JNA in the skull base, such as the sphenoid sinus, the base of pterygoids and clivus, and the cavernous sinus and anterior fossa (3–5). In our series, the most frequent location of RD and recurrences was at the base of the pterygoids. This intraosseous location of RD and recurrences emphasizes the need for drilling the base of pterygoids, as Howard et al recommend (5). Second, the appearance of RD may be modified by embolization, which may durably reduce blood flow and, subsequently, contrast enhancement. Since the degree of enhancement reflects tissue vascularity, potential RD may not be apparent because embolization and surgery decreases or stops the blood supply. Inversely, the possibility of artifacts related to the potential diffusion of cyanoacrylates outside the tumor have led our team to reconsider the indications and progressively give up the use of direct embolization (three patients in our series).

Surprisingly, the use of early postoperative imaging after JNA excision for the early diagnosis and treatment of RD has attracted little interest in the literature. Postoperative imaging studies that have been reported usually took place between 6 weeks and 6 months after surgical excision (6, 7, 9). CT had been done 6 weeks after surgery to identify all recurrent or persistent tumors before they became symptomatic (6) or to record the patient’s postoperative status (7); however, they were performed not to initiate early management of RD. In our institution, we designed a specific protocol using early postoperative CT to plan early revision surgery when appropriate. This treatment philosophy bypasses the concept of spontaneous regression of RD (16). Because minimally invasive revision surgery may remove the RD in most instances (17), it should be done to reduce the recurrence rate. This early endoscopic treatment may avoid the need for further embolization or radiation therapy. Long-term follow-up is required to determine whether this concept of early postoperative CT combined with early revision surgery decreases the recurrence rate of JNA that erodes the skull base.

Our study had some limitations. First, the number of patients was relatively small, though this is directly correlated to the rare occurrence of JNA. Second, the final diagnosis was rendered on the basis of clinical and radiologic follow-up in patients with negative results (i.e., when no RD was detected on CT scanning). Most recurrences appear in the first 24 months of follow-up (4). In our study, the mean follow-up was 42 months, ranging from 2 to 6.3 years. The wide range of 95% CIs for the results might provide a safety margin for the mean sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. Therefore, few changes are expected in the evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of early postoperative CT with further follow-up. Third, interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility in the detection of RD was not evaluated in this study.

Conclusion

Our findings suggests that early postoperative CT is reliable in detecting or excluding RD in patients with JNA. Results of larger studies are necessary to confirm whether early postoperative enhanced CT affects optimal therapeutic management and high recurrence rates associated with JNA involving the skull base.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen O’Leary, MD, and Natacha Crozat-Teissier, MD, for their helpful assistance in correcting the manuscript and Gabriel Thabut, MD, for his advice and contribution to the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Lloyd G, Howard D, Lund VJ, Savy L. Imaging for juvenile angiofibroma. J Laryngol Otol 2000;114:727–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neel H, Whicker J, Devine K, Weiland L. Juvenile angiofibroma. Review of 120 cases. Am J Surg 1973;126:547–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd G, Howard D, Phelps P, Cheesman A. Juvenile angiofibroma: the lessons of 20 years of modern imaging. J Laryngol Otol 1999;113:127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman P, Lot G, Chapot R, Salvan D, Huy PT. Long-term follow-up of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: analysis of recurrences. Laryngoscope 1999;109:140–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard DJ, Lloyd G, Lund V. Recurrence and its avoidance in juvenile angiofibroma. Laryngoscope 2001;111:1509–1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Kassam AB, Jungreis CA. Endoscopic and endoscopic-assisted surgery for juvenile angiofibroma. Laryngoscope 2001;111:483–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholtz AW, Appenroth E, Kammen-Jolly K, Scholtz LU, Thumfart WF. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: management and therapy. Laryngoscope 2001;111:681–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandler J, Goulding R, Moskowitz L. Nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: staging and management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1984;93:322–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorissen M, Eloy P, Rombaux P, Bachert C, Daele J Endoscopic sinus surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 2000;54:201–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radkowski D, McGill T, Healy GB, Ohlms L, Jones DT. Angiofibroma: changes in staging and treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:122–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tewfik TL, Tan AK, al Noury K, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. J Otolaryngol 1999;28:145–151 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ungkanont K, Byers RM, Weber RS, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: an update of therapeutic management. Head Neck 1996;18:60–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran Ba Huy P, Borsik M, Herman P, Wassef M, Carasco A. Direct intratumoral embolization of juvenile angiofibroma. Am J Otolaryngol 1994;15:429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carasco A, Herbeteau D, Houdart E, et al. Devascularization of craniofacial tumors by percutaneous tumor puncture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:1233–1239 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohar JE, Duvall AJ III. Spontaneous regression of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1992;101:469–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roger G, Tran Ba Huy P, Froehlich P, et al. Exclusively endoscopic removal of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: trends and limits. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;128:928–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]